Abstract

Young adults face stressful role transitions as well as increased risk for poor mental health, but little is known about a “natural course” of response to such events. We used the PHQ-2 to characterize the trajectory of depressive symptoms before, during, and after relationship breakup and examined subjective appraisal and sense of control as moderators. In our sample of participants reporting a single breakup during the 2-year study period (N=156), breakup was associated with a temporary increase in depressive symptoms that returned to pre-breakup levels within three months. We observed increased symptoms among negatively appraised, but not positive or neutral, events. A general low sense of control was associated with higher depressive symptoms at all time points. Our results suggest that a natural course of response to young adult breakups is characterized by recovery within three months and that subjective appraisal and sense of control contribute to this adaptive response.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, young adulthood, transitions to adulthood, subjective appraisal, sense of control, romantic relationships

Introduction

Young adulthood is characterized by an elevated prevalence of mental health problems (Arnett, 2000; Kessler et al., 2005; Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). An estimated 22% of American young adults (7.6 million) meet criteria for mental health disorders every year, with 14% presenting with anxiety disorders and 17% with depressive disorders (Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2010). Recent increases in the prevalence of anxiety (Goodwin, Weinberger, Kim, Wu, & Galea, 2020), depression (Mojtabai, Olfson, & Han, 2016), and incidence of suicide (Han et al., 2018) among young adults underscores the urgency for studying this developmental period.

Role transitions characteristic of young adulthood in the domains of education, living situations, employment, romantic relationships, and parenting (Osgood et al., 2005; Settersten Jr, 2007) are associated with increased risk for poor mental health. For instance, the school-to-work transition (employment domain) is associated with a slowdown in longer-term trends of self-esteem increase (Filosa, Alessandri, Robins, & Pastorelli, 2022). Transitions into marriage (romantic relationship domain) are associated with improved mental health and decreased substance use (Bachman et al., 2014), while the dissolution of these relationships are associated with increased psychological distress (Davis, Shaver, & Vernon, 2003) and alcohol use (Fleming et al., 2018; Fleming, White, & Catalano, 2010).

Role transitions may thus be stressful events that produce psychological distress (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981), and the Transitions Overload Model suggests that the cumulative impact of role transitions in young adulthood account for the elevated mental health and substance use risk (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Carr, 2014). Young adults who experience more transitions within a month and across a 24-month period engage in more alcohol use across that time (Patrick et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2018). Role transitions are associated with within-person increases in drinking behaviors in the month in which the role transitions occur (Cadigan et al., 2021; Fleming et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2020). Consistent with psychological distress as a mediator of the pathway, recent evidence clarified that transitions subjectively appraised as negative, rather than the number experienced, drive negative health behaviors (Cadigan et al., 2021).

The Transitions Overload Model provides a conceptual framework for understanding the long-term relationship between cumulative stressful transitions and psychological distress. Yet, role transitions, while associated with increased risk for psychological distress, are also crucial to individual growth and learning in this developmental period. It is thus important to understand the short-term process by which young adults respond to and adapt to such stressful transitions to promote healthy development in conjunction with important developmental experiences.

Evidence suggests that, in most cases young adults find ways to cope with the stress associated with role transitions. In this way, developmentally normative transitions may trigger a response within young adults like an immune response. Among those with healthy immune systems, a viral exposure catalyzes a series of biological reactions that lead to recovery within several weeks. This adaptive response means that symptoms, while unpleasant, are transient, and repeated but moderate exposures help strengthen the immune system. While research documents the negative risks associated with role transitions, less is known about their relationship to normative responses to stressful events or about the characteristics of an adaptive response in young adults.

Medical providers have characterized the immune response to viral exposure, including anticipated symptoms, bodily responses, and time to recovery. Understanding this “natural course” of illness and recovery allows healthcare providers to identify atypical illness and intervene appropriately. Conversely, little is known about the natural course of response and recovery following stressful events in young adults. More understanding of the expected trajectory of recovery from stressful events can help inform whether and when intervention is needed. However, studies focused on major or one-time role transitions, such as marriage (Bachman et al., 2014) or the school-to-work transition (Filosa et al., 2022), are ill-suited to studying this natural course. Studying major transitions is akin to studying severe immune disease, while repeated but moderately stressful transitions are more closely related to the common viral exposures that elicit an ordinary immune response. Understanding the natural course of response to stressful events requires studying smaller life changes (Patrick et al., 2018).

Breakups, distress, and recovery in young adults: Unanswered questions

The dissolution of a romantic relationship (“breakups”) in young adulthood is one such life change. Young adults are likely to engage in multiple relationships before entering a relationship such as marriage, and breakups are associated with psychological distress (Fleming et al., 2018). Given the widespread and common nature of breakups, neither prevention of exposure nor systematic intervention is reasonable, and most young adults eventually recover from breakup-induced distress. Breakups are thus a type of repeated, yet moderately stressful event characteristic of this developmental period. Improved understanding of a breakup’s anticipated effects as well as a reasonable time-frame for recovery would further understanding of the natural course of response to stressful events.

The ending of a romantic relationship during any developmental stage is a stressful experience associated with increased psychological distress. Yet, in the context of divorce, set-point theory and related evidence suggest that the emotional distress brought about by the relationship’s dissolution dissipates within five years (Asselmann & Specht, 2022a, 2022b). In some cases, the years following separation are characterized by improved mental health in absolute, and not merely relative, terms (Preetz, 2022). This suggests that individuals largely find ways to cope with and adapt to divorce-induced distress, and that this process takes place in the time frame of years.

Less is known about the specific and time-varying impacts of breakup on young adult mental health. Whether, how, and within what time frame young adults adapt to the breakup-induced distress is unknown. While the risk of poor mental health following a breakup may be concerning, temporary psychological distress in such a situation is neither surprising nor concerning. Yet, prolonged distress may be indicative that an individual’s adaptive responses is not functioning optimally. Greater understanding of the natural course of response to stressful events and elements that promote an adaptive response and recovery would contribute to more effective identification of and support for young adults at higher risk of mental illness following breakup.

Depressive symptomology and young adult breakups

Depressive symptoms are a particularly salient mental health outcome in the context of breakups. Cognitive models describe depression as an adaptation to conserve energy after “the perceived loss of an investment in a vital resource such as a relationship”(Beck & Bredemeier, 2016). Depressive symptoms may change quickly, and screening tools to measure them have been validated in the general population (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Löwe, 2009). Depressive symptoms are more straightforward to collect than biomarkers such as cortisol, making them a pragmatic and appropriate measure for distress trajectory following breakup. Consequently, we focus on depressive symptoms as our mental health outcome in the context of breakup in young adulthood.

Potential moderators of the stress response

Given the personal and public health burden of poor mental health, interest in understanding response to stressful events goes hand in hand with further investigation into strategies for promoting its optimal function. Here we propose two moderators of the response in the breakup context with an eye towards modifiable factors.

Cognitive appraisal

Cognitive models of mental health implicate cognitive appraisal as a modifiable contributor to mental distress. Contrary to models that treat a role transition’s impact as inherent and immutable (i.e., “all breakups are bad” (Holmes & Rahe, 1967)), cognitive models posit that an individual’s subjective experience of the event, driven by underlying cognitive interpretations, is the salient factor driving psychological outcomes. Growing evidence supports the role of subjective impact, over and above the event itself, in predicting mental health outcomes (Cadigan et al., 2021; Mirowsky & Ross, 2003). As a clinical application of this insight, cognitive behavioral therapy is built around the modification of negative, or maladaptive, cognitions to treat depression and other mental illnesses (Powers, de Kleine, & Smits, 2017). However, while the mechanism of changing underlying cognitions has both theoretical and clinical support, its application to subclinical populations experiencing developmentally normative stressful role transitions remains understudied.

Sense of control

Researchers studying resilience have identified protective factors in the face of stressful events. For instance, childhood protective factors include healthy attachment, self-regulation systems, and mastery motivation (Doty, Davis, & Arditti, 2017; Masten, 2015; Wright, Turanovic, O’Neal, Morse, & Booth, 2019). Salient stressors, outcomes, and relevant adaptive systems, however, differ across developmental periods. The developmental tasks facing young adults in the professional, social, and living domains differ from those facing children.

Sense of control, the extent an individual feels they, versus external factors, have control over their life, may be especially important for young adults (Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2013; Steptoe & Wardle, 2001). In young adulthood, control is shifting away from parents and other caretakers towards the young adults themselves. Evidence illustrates the positive association between sense of control and young adult mental health (Gómez-López, Viejo, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2019; Rauer, Pettit, Lansford, Bates, & Dodge, 2013). The extent to which the individual feels in control of these changes contribute to their mental health trajectory following stressful role transitions. In addition, evidence-based interventions promoting resilience focus on sense of control as a key modifiable factor (Ludolph, Kunzler, Stoffers-Winterling, Helmreich, & Lieb, 2019). Sense of control as a trait-like moderator of the dynamic trajectory of mental health in the context of relationship breakup, however, has not been explored.

Current Study

Using data collected from a longitudinal study of young adults surveyed monthly for 24 months, this study has three aims. For Aim 1, we describe the trajectory of depressive symptoms among young adults reporting relationship breakup in the months leading to, concurrent with, and after breakup to examine whether there exists a common trajectory, potentially indicative of an underlying “natural course” of response to stressful events. For Aim 2, we examine appraisal of the breakup as a moderator of this trajectory, testing whether negative appraisal is associated with longer-lasting depressive symptoms. For Aim 3, we investigate individual sense of control as a moderator of the trajectory, assessing whether individuals with higher sense of control will experience fewer depressive symptoms compared to individuals with a lower sense of control.

Method

Participants & Procedures

Participants were a community sample of young adults recruited for a longitudinal investigation of social role transitions and health behaviors during young adulthood. Participants were recruited in 2015 and 2016 via print, online, and social media advertisements, fliers, outreach, and friend referral. Participant eligibility was based on age (18—23 years at screening), alcohol consumption (≥1 drink in the past year), and location (residing in a zip code within 60 miles of Seattle, WA in the United States where the study office was located).

Identity and age for eligible individuals were determined during an initial, in-person session which included completed a web-based baseline assessment. A total of 778 participants completed monthly surveys. In the 24 months following, participants completed monthly surveys online. Each survey period was open for 7–10 days, with reminders sent via e-mail, text message, and telephone. Participants received a $40 Amazon gift card upon completion of an online baseline assessment and additional compensation for each completed survey (up to $770 total). Additional recruitment details are provided elsewhere (Patrick et al., 2018). This study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

For the current study, the sample was a subset of participants who reported only one breakup during the 24 months of data collection (n=156). In this sample, 50% were women, and self-reported racial identifications were 58% White, 11% Asian, 3% Black, and 27% Other. At baseline, 51% were enrolled in a 4-year college, and 53% were employed. Mean age at breakup was 21.3 (SD=1.75). Participants with multiple breakups were excluded due to concerns that unobserved factors contributing to the experience of multiple breakups may also be associated with depressive symptoms. Sensitivity analyses used the sample of participants reporting any breakup, including multiple breakups during the 2-year study period (N=345). Sensitivity analysis results are reported in the Supplemental Appendix.

Measures

Relationship Status

Participants reported changes in their relationship status at each month, selecting from a list of 18 statements covering new relationships (e.g., “Went on a first date”), existing relationships (e.g., “Decided with a partner to no longer use birth control”), and ending relationships (e.g. “Decided to separate or be on a break”). For the present study, breakup events were defined as months in which participants selected the following responses: “Decided to separate or be on break”; “Relationship ended, became single”; and “Moved out, no longer living with partner.”

The month of the reported breakup was coded as the index month (t=0), and we examined the three months before (coded as −3 to −1) and after (coded as 1 to 3) the index month. Breakup events in the first and last months of the 24-month study period were excluded. For participants who reported breakup events in consecutive months, representing potentially drawn-out relationship instability, we treated the last month as the reference month after which adaptation and recovery could begin.

Subjective appraisal of relationship impact

Participants who reported a relationship transition were asked: “For each change/experience, please indicate the extent to which you viewed the change in relationship situation as having either a positive or negative impact on your life.” Response options ranged on a 5-point scale from 0 (“Extremely negative”) to 4 (“Extremely positive”). Negative events were defined as events rated as 0 (“Extremely negative”) or 1 (“Negative”). Non-negative events were defined as those rated as 2 (“No Impact”), 3 (“Positive”), or 4 (“Extremely Positive”).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured monthly using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), a validated clinical screening tool for major depressive disorder (Manea et al., 2016). Participants were asked how often during the past two weeks 1) they felt little interest or pleasure in doing things, and 2) they felt down, depressed, or hopeless. Response options are presented on a scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Nearly every day”). The summed score of the two items was used for this analysis.

Sense of control

Individual perceived control was measured in month 6 of the study using an adapted 3-item version of the Perceived Control Scale (PCS) (α=0.70) (Eizenman, Nesselroade, Featherman, & Rowe, 1997). We dropped one item because it referred specifically to health-related perceived control, as opposed to general perceived control, and summed scores to produce a single score. The PCS asks participants to rate the degree to which they agree with the following three statements: “Other peoples’ attitudes and actions determine how happy I am,” “Events outside of my control determine how happy I am,” and “Sometimes I feel that I am being pushed around in life.” Response options range from 1 (“Agree strongly”) to 4 (“Disagree strongly”). Higher scores indicated greater levels of perceived control. Consistent with prior conceptualizations of control (Asselmann & Specht, 2022b; Skinner, 1996; Specht et al., 2013), we coded this variable as a binary variable split at the median score of 7 (0: high control, 1: low control).

Demographic controls

Age (0: <21, 1: 21+), sex (0: female; 1: male), race (0: white; 1: other race), and educational enrollment (0: enrolled in 4-year college; 1: not enrolled) were included as covariates based on associations with depression symptoms and likelihood of experiencing a breakup during the study period. Demographic variables were assessed at baseline.

Data Analysis

For primary analyses, we used multilevel spline models with a random intercept to examine average depressive symptom trajectory. Piecewise linear splines were used to model the non-linear trajectory over time. Our models used all available data, such that missing responses were dropped but participants with some incomplete data remained in the analysis. In our models, we divided the time frame into four segments using 3 knots (1 month prior to breakup, month of breakup, and month following breakup). Four segments were chosen as the minimum able to capture change over time while maintaining a relatively parsimonious model. Four estimated slope coefficients correspond to monthly rate of change in each time segment. Negative binomial forms of the model accounted for positive skewness and over-dispersion in the depressive symptom outcome. We follow conventions with count regression models and estimate count ratios (exponentiated coefficients) that describe the proportional change in the outcome (depressive symptom score) associated with a 1-unit increase in the covariate, conditional on the random intercept. Figures plot the marginal estimated effect holding other variables constant at their mean value.

For our first aim, we modeled the mean trajectory of depressive symptoms in our sample in the three months before and after the breakup. For our second aim, we included interaction terms between our spline time terms and binary appraisal of breakup impact. For our third aim, we included only breakup events appraised as negative and specified interaction terms between our spline time terms and binary sense of control. In all models, we controlled for demographic controls previously described.

All statistical analysis were performed using R 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020). The “glmmTMB” package was used for multi-level modeling (Brookes et al., 2017), the “lspline” package to incorporate linear piecewise spline functions into the multilevel models (R Core Team, 2020), the “ggeffects” package for calculating marginal effects, and “ggplot2” for plotting model results (Lüdecke, 2018).

Results

Descriptive Information

Table 1 presents sample characteristics. Fifty-three percent of participants appraised their breakup as negative. The average perceived control score was 7.7 (SD: 1.95). The mean PHQ-2 score prior to breakup was 1.36 (SD: 1.51).

Table 1:

Sample characteristics

| All breakups (Aims 1 & 2) N=156 |

Negative breakups (Aim 3) N=82 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean / N | SD / % | Mean/N | SD/% | |

| Age at breakup | 21.3 | 1.75 | 21.6 | 1.69 |

| Female | 75 | 50% | 38 | 50% |

| Race | ||||

| Asian or South Asian | 17 | 11% | 11 | 13% |

| Black or African American | 5 | 3% | 2 | 2% |

| Caucasian or White | 91 | 58% | 48 | 59% |

| Other | 43 | 27% | 21 | 26% |

| Educational enrollment | ||||

| 4-year college | 80 | 51% | 42 | 51% |

| 2-year college | 32 | 21% | 12 | 15% |

| Not enrolled or other | 44 | 28% | 28 | 34% |

| Sense of control (range: 0–12) | 7.71 | 1.95 | 7.54 | 2.02 |

| Pre-breakup PHQ2 (range: 0–6) | 1.36 | 1.51 | 1.37 | 1.53 |

| Breakup appraisal | ||||

| Negative | 74 | 47% | - | - |

| Neutral/Positive | 82 | 53% | - | - |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | - | - |

Depressive symptom trajectory and romantic breakup

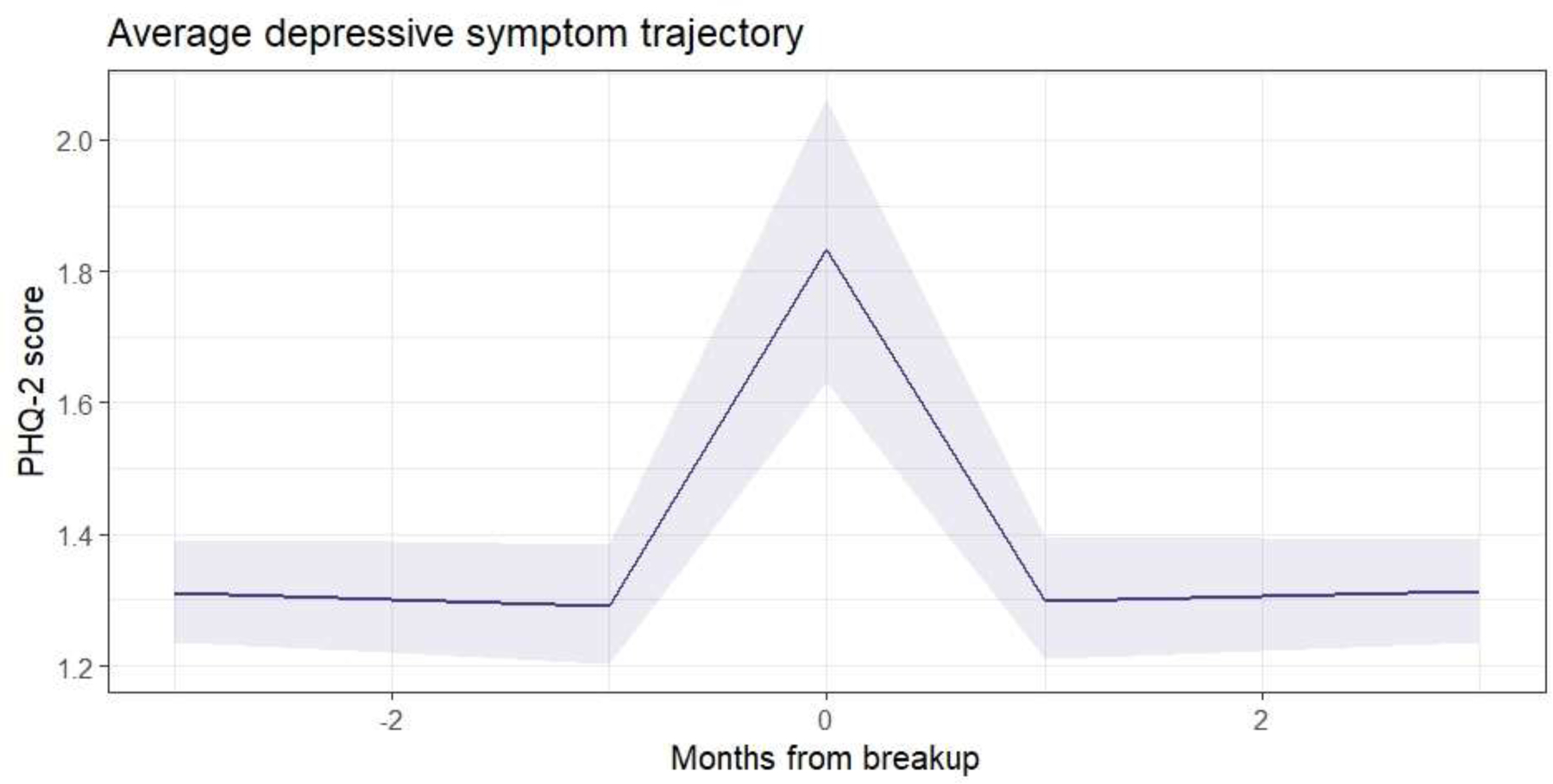

For Aim 1, we modeled depressive symptoms in the three months prior to and following the reported breakup event, controlling for covariates. Figure 1 shows the estimated trajectory with 95% confidence interval, and regression coefficients are presented in Table 2. Controlling for covariates, depressive symptom scores increased on average by 24% in the month of the breakup, followed by an equivalent decline in the following month. On average, depressive symptoms return to pre-breakup levels within three months after breakup.

Figure 1:

Average depressive symptom trajectory in the 3 months prior to and following romantic breakup (Model 1)

Table 2:

Regression results for Model 1, mean depressive symptom trajectory during romantic breakup

| Estimate (β) | Count Ratio (exp(β)[95% CI]) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | |||

| Time 1: months −3 to −1 | −0.01 | 0.99 [0.98, 1.00] | 0.042 |

| Time 2: months −1 to 0 | 0.29 | 1.33 [1.17, 1.53] | <0.001 |

| Time 3: months 0 to 1 | −0.27 | 0.76 [0.66, 0.87] | <0.001 |

| Time 4: months 1 to 3 | −0.00 | 1.00 [0.99, 1.00] | 0.661 |

| Intercept | −0.22 | 0.80 [0.58, 1.10] | 0.168 |

| Age (>21 years) | 0.31 | 1.37 [1.00, 1.87] | 0.048 |

| Race (Non-White) | 0.17 | 1.18 [0.88, 1.60] | 0.273 |

| Education (Not enrolled in college) | 0.14 | 1.15 [0.84, 1.56] | 0.380 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.08 | 0.92 [0.69, 1.24] | 0.592 |

| Random effects (variance) | 0.77 | ||

| Sample size | 156 |

Month 0: Month of breakup

Depressive symptom trajectory and appraised impact

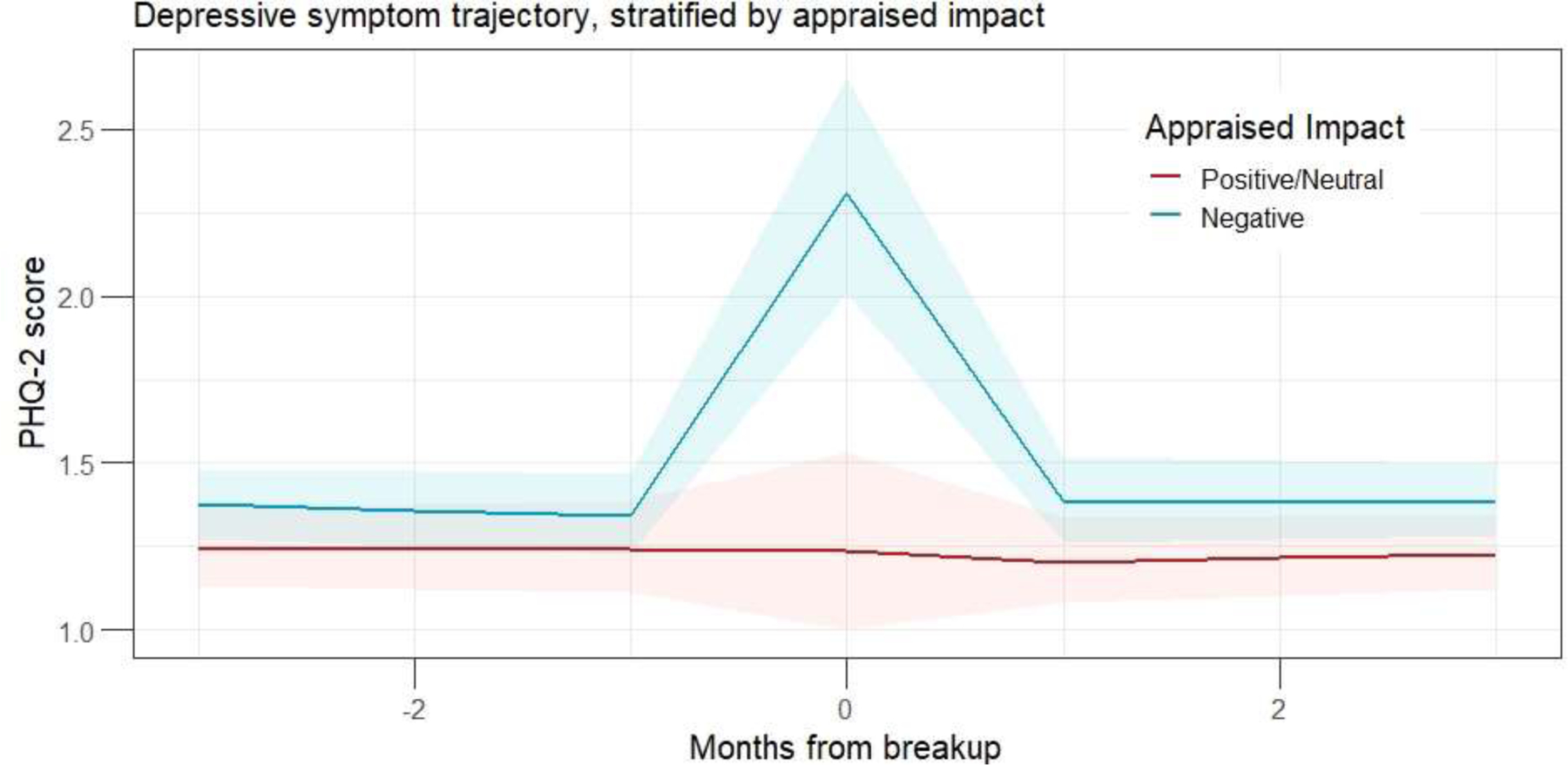

For Aim 2, we assessed appraised impact as a moderator. Figure 2 shows the estimated trajectories with 95% confidence interval bands, and regression results are presented in Table 3. No notable change in depressive symptoms was observed following breakup events not appraised as negative (p > 0.6 in all cases). Conversely, a clear increase in depressive symptom scores can be seen at the time of breakup for those rated as negative, indicating greater mental distress. On average, depressive symptoms were 57% higher in the month of negative breakup compared to the month prior to the breakup. The month after the breakup showed a 45% decrease in depressive symptoms. Among those who appraised the breakup as negative, depressive symptoms returned to pre-breakup levels within three months following breakup.

Figure 2:

Average depressive symptom trajectory moderated by appraised impact of breakup (Model 2)

Table 3:

Regression results for Model 2, depressive symptom trajectory moderated by appraised impact

| Estimate (β) | Count Ratio (exp(β)[95% CI]) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | |||

| Time 1: months −3 to −1 | −0.00 | 1.00 [0.98, 1.01] | 0.630 |

| Time 2: months −1 to 0 | −0.00 | 1.00 [0.78, 1.27] | 0.968 |

| Time 3: months 0 to 1 | 0.02 | 1.02 [0.80, 1.30] | 0.888 |

| Time 4: months 1 to 3 | 0.01 | 1.01 [1.00, 1.02] | 0.093 |

| Impact | |||

| Time 1*Impact | −0.01 | 0.99 [0.97, 1.01] | 0.300 |

| Time 2*Impact | 0.45 | 1.57 [1.17, 2.11] | 0.003 |

| Time 3*Impact | −0.45 | 0.64 [0.48, 0.86] | 0.003 |

| Time 4*Impact | −0.02 | 0.98 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.012 |

| Impact (Negative impact) | 0.28 | 1.33 [0.96, 1.84] | 0.086 |

| Intercept | −0.37 | 0.69 [0.48, 0.99] | 0.043 |

| Age (>21 years) | 0.28 | 1.32 [0.97, 1.80] | 0.081 |

| Race (Non-White) | 0.17 | 1.19 [0.88, 1.61] | 0.256 |

| Education (Not enrolled college) | 0.16 | 1.17 [0.87, 1.59] | 0.301 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.09 | 0.92 [0.69, 1.23] | 0.563 |

| Random effects (variance) | 0.76 | ||

| Sample size | 156 |

Depressive symptom trajectory and sense of control

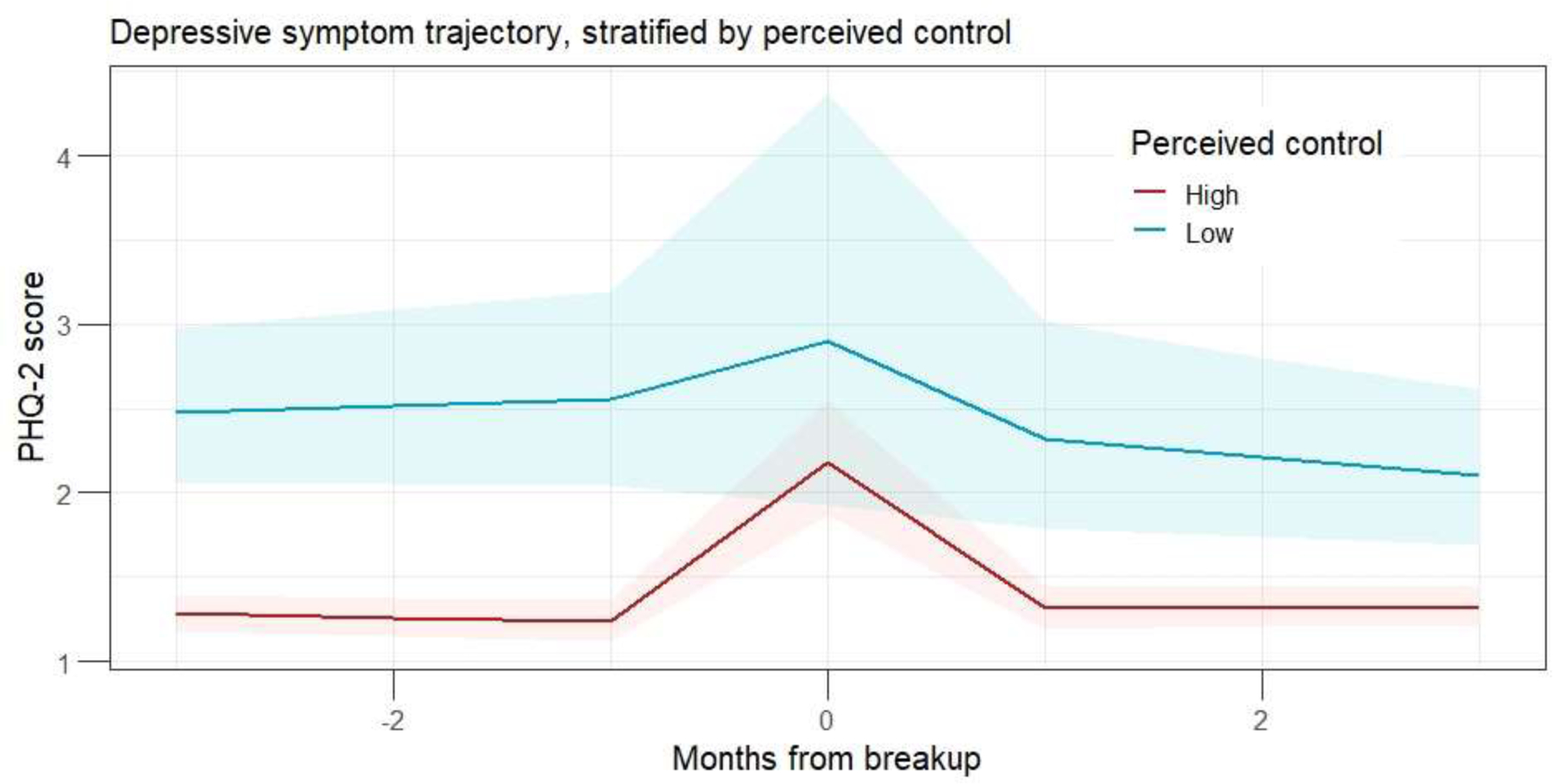

Because results from Aim 2 suggested that negative breakups drove the observed trajectory of distress and recovery, we limited our analysis for Aim 3 to negatively appraised breakups (n=82) and included perceived sense of control as a moderator. Figure 3 shows the estimated trajectories with 95% confidence interval bands, and Table 4 reports regression results. Overall, the rate of change in depressive symptoms within any of the time intervals was not statistically significantly different comparing individuals with high and low sense of control. Among those with high control experiencing a negative breakup, depressive symptoms increased 63% in the month of breakup and decreased 37% in the month following. Among those with low control, the month of breakup was associated with a 17% increase in depressive symptoms followed by a 13% decrease. In both groups, an increase in depressive symptom scores is seen at the time of breakup followed by return to baseline levels in the following month. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the change over time by sense of control, depressive symptom scores among individuals with low sense of control were 2.16 times higher across all time points compared to those with high sense of control (p=0.019).

Figure 3:

Depressive symptom trajectory moderated by perceived sense of control (Model 3)

Table 4:

Regression results for Model 3, depressive symptom trajectory moderated by sense of control

| Estimate (β) | Count Ratio (exp(β)[95% CI]) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | |||

| Time 1: months −3 to −1 | −0.02 | 0.98 [0.97, 1.00] | 0.007 |

| Time 2: months −1 to 0 | 0.49 | 1.63 [1.35, 1.96] | <0.001 |

| Time 3: months 0 to 1 | −0.46 | 0.63 [0.53, 0.76] | <0.001 |

| Time 4: months 1 to 3 | −0.00 | 1.00 [0.99, 1.01] | 0.549 |

| Perceived Control | |||

| Time 1*Control | 0.02 | 1.02 [0.99, 1.05] | 0.181 |

| Time 2*Control | −0.33 | 0.72 [0.43, 1.19] | 0.197 |

| Time 3*Control | 0.31 | 1.37 [0.81, 2.32] | 0.236 |

| Time 4*Control | −0.05 | 0.94 [0.91, 0.98] | 0.001 |

| Control (Low control) | 0.77 | 2.16 [1.13, 4.13] | 0.019 |

| Intercept | −0.00 | 1.00 [0.64, 1.55] | 0.996 |

| Age (>21 years) | 0.22 | 1.25 [0.84, 1.85] | 0.276 |

| Race (Non-White) | 0.16 | 1.17 [0.80, 1.72] | 0.411 |

| Education (Not enrolled in college) | −0.18 | 0.84 [0.57, 1.23] | 0.365 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.12 | 0.89 [0.61, 1.28] | 0.526 |

| Random effects (variance) | 0.62 | ||

| Sample size | 82 | ||

Secondary analysis was conducted to investigate whether perceived control was correlated with appraisal such that the lack of moderation reflected imbalances in the sample. Perceived control and appraised impact were correlated 0.08, and a Chi-Squared Test of Independence showed no statistically significant differences of levels of perceived control by appraised impact (p=0.196). Additional analyses using the full sample of all participants who reported any breakup, including those who reported multiple breakups during the study period, produced similar conclusions (results available in the Supplemental Appendix).

Discussion

Our findings provide preliminary evidence for a natural course of response to young adult breakups characterized by a trajectory of temporary distress followed by recovery. On average in our sample of participants who reported a single breakup during the study period, depressive symptoms increased in the month of breakup and returned to pre-breakup levels within three months. Consistent with prior research (Cadigan et al., 2021), subjective appraisal moderated this trajectory such that this temporary increase was restricted to those with negative appraisal of the breakups. Among those with positive or neutrally appraised breakups, there was no statistically significant increase in depressive symptomology during the month of breakup. We also observed that sense of control did not significantly moderate the rates of change of depressive symptoms in any of the time intervals relative to the breakup. Sense of control was associated, however, with a higher level of symptomology at all points.

Prior research has shown the association between role transitions and young adult mental health (Cadigan, Duckworth, Parker, & Lee, 2019; Cadigan et al., 2021; Fleming et al., 2018; Hanna et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2018). Results from this study contribute to the literature by characterizing the trajectory and time-frame of stress response and recovery in young adults in the absence of intervention. These results are consistent with set-point theory (Asselmann & Specht, 2022a, 2022b) applied in the context of marriage and divorce. To our knowledge, this study is the first to document this trajectory in young adulthood.

Our results suggest that adaptation and recovery is the modal response in young adults to relationship breakups (Bonanno, 2005, 2021). We interpret this as preliminary evidence for an adaptive capacity in response to stressful events within young adults. We use the metaphor of the common cold to suggest that, among young adults with healthy stress-response systems, recovery from breakup may be expected within three months. As would be expected, this time frame is notably shorter than the five-year period observed for divorce. In both cases, however, a trajectory of temporary distress followed by eventual recovery followed the stressful transition. Taken together, this evidence suggests that continued investigation into the natural course of response and recovery following stressful events may be fruitful.

By contrast, prolonged negative impacts or sub-optimal recovery may reflect underlying issues that threaten the individual’s adaptive capacity. Resilience researcher Ann Masten posits that the healthy functioning of common adaptive systems spanning social, behavioral, and psychological domains promotes recovery following stressful events (Masten, 2015). Prolonged psychological distress lasting longer than three months following breakup may be indicative that elements of these adaptive systems are not functioning at optimal levels. Our results examined two such elements: cognitive appraisal and sense of control.

First, young adults who did not appraise the breakup as negative—approximately one-half of breakups—did not experience an increase in depressive symptoms. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that this difference is due to unmeasured breakup characteristics, this finding is consistent with literature illustrating the effectiveness of cognitive therapies (Bernecker et al., 2020; Mewton & Andrews, 2016). Second, though sense of control did not modify the shape of the trajectory following breakup, young adults in our sample with high sense of control experienced fewer depressive symptoms at all time points. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that sense of control may generally support mental health. The capacity to reframe a breakup as neutral or positive, as well as a healthy generalized sense of control, may be two characteristics of an adaptive response to stressful breakup.

These findings have implications for prevention and treatment of poor mental health in young adults. For instance, interventions that teach cognitive appraisal skills or foster a sense of control may contribute to a prompter recovery, similar to how a balanced diet and exercise support immune function. Treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapies, as well as experiences fostering a sense of control, may improve rates of recovery among those experiencing prolonged distress. While these interventions have already shown to be effective, the current study contextualizes their therapeutic mechanisms within a natural course of response and recovery stressful breakup.

As a common and developmentally normative event, reducing breakup experiences is not a desirable strategy, and our results suggest that most young adults will recover. However, improved understanding of an expected trajectory of recovery may normalize temporary psychological distress and promote targeted intervention for young adults experiencing atypical trajectories of distress.

Future directions

Our longitudinal dataset, which included monthly measures and detailed information on role transitions, provided an opportunity to study the natural course of response to stressful events in young adults by characterizing the short-term trajectory of mental health symptoms in the context of relationship breakup. However, important study limitations remain. Our unit of analysis was months, while both breakups and symptoms may occur over days. The possibility that reported depressive symptoms were experienced before, during, or after the actual breakup cannot be ruled out. Consistent with existing literature and to ensure model parsimony, we dichotomized continuous variables. This may have dropped meaningful information and biased results. Our outcome measure relied on the two-item version of the PHQ. While the PHQ-2 is a brief tool, its validity and reliability in the general population has been well-documented (Khubchandani, Brey, Kotecki, Kleinfelder, & Anderson, 2016; Kroenke et al., 2009; Löwe et al., 2010; Materu et al., 2020). In addition, use of this brief screening tool contributed to reduced participant burden and higher retention through this longitudinal study. Its benefits with regards to robust follow-up balanced out its limitations. It will be important for our results to be replicated in future research using more detailed data and with alternate outcome measures.

Though we included important individual covariates, the presence of confounding or the risk of bias cannot be ruled out and remains a limitation. Unmeasured breakup characteristics, such as length of relationship, relationship quality, or breakup initiator, may have confounded results. Conditioning our sample on breakup experience may contribute to bias.

It will be important for this question to be studied in diverse populations. Our community sample was recruited primarily from online sources and was disproportionately White and college-educated. In addition, study eligibility criteria excluded young adults who do not drink alcohol (≈15% of interested participants). Efforts to generalize our results must be made with caution and with great attention to similarities or differences between our study sample (as reported in Table 1) and the target population.

Despite empirical and theoretical support for the association between both positive subjective appraisals and greater sense of control and better mental health, clinical application must be made with great care. Using these results to develop interventions risks ignoring the role of systemic disadvantage. Simple causal models linking subjective appraisal and sense of control to mental health and depressive symptoms do not consider structural and social contexts and risk placing disproportionate responsibility on individuals. The current study is not intended to encourage frameworks that ignore context, nor do we conclude that individuals need simply to “think their way out of hardship” or “take control of their lives.” We reiterate that our sample was characterized by structural advantage, and that environments of disadvantage may supersede individual resources. Careful examination of individual resources within social and structural contexts is needed to inform the development of effective preventive interventions.

It will be important for future research to continue exploring predictors and risks to optimal and adaptive response to stressful breakup in young adults. The current study suggests that the natural course of depressive symptoms following relationship breakup in young adults is one of transient distress followed by recovery. At the same time, there are young adults for whom stressful role transitions have lasting negative impact. It will be important for future research to explore which factors contribute to identifying those individuals at higher risk of mental health problems and whether a targeted intervention strategy would be more appropriate.

Conclusion

In the current study, we characterized the short-term trajectory of depressive symptoms in the absence of intervention of young adult mental health in the context of relationship breakup. Our results provide preliminary support for a natural course of response to stressful breakup characterized by transient distress and recovery within 3 months of the breakup. It will be important for our results to be replicated in diverse populations and with alternative mental health outcomes, and for future research to continue exploring predictors and risks to adaptive stress response in young adults.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (CL, grant numbers R01AA022087 and R01AA027496), as well as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (JA, grant number T32HS013853). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American psychologist, 55(5), 469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselmann E, & Specht J (2022a). Changes in happiness, sadness, anxiety, and anger around romantic relationship events. Emotion [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselmann E, & Specht J (2022b). Personality growth after relationship losses: Changes of perceived control in the years around separation, divorce, and the death of a partner. PloS one, 17(8), e0268598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, & Merline AC (2014). The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Bredemeier K (2016). A Unified Model of Depression:Integrating Clinical, Cognitive, Biological, and Evolutionary Perspectives. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(4), 596–619. doi: 10.1177/2167702616628523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernecker SL, Zuromski KL, Curry JC, Kim JJ, Gutierrez PM, Joiner TE, . . . Bryan CJ (2020). Economic Evaluation of Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs Treatment as Usual for Suicidal US Army Soldiers. JAMA psychiatry, 77(3), 256–264. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current directions in psychological science, 14(3), 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA (2021). The End of Trauma: How the new science of resilience is changing how we think about PTSD New York: Basic Books. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes M, Kristensen K, van Benthem K, Magnusson A, Berg C, Nielsen A, . . . Bolker B (2017). glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. The R Journal, 9(2), 378–400. Retrieved from https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2017/RJ-2017-066/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan JM, Duckworth JC, Parker ME, & Lee CM (2019). Influence of developmental social role transitions on young adult substance use. Current opinion in psychology, 30, 87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan JM, Fleming CB, Patrick ME, Lewis MA, Rhew IC, Abdallah DA, . . . Lee CM (2021). Negative evaluation of role transitions associated with perceived stress and alcohol-consequences: Examination of the transitions overload model in young adulthood using two years of monthly data. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(8), 1607–1615. doi: 10.1111/acer.14636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D (2014). Worried Sick: How Stress Hurts Us and How to Bounce Back: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Shaver PR, & Vernon ML (2003). Physical, emotional, and behavioral reactions to breaking up: The roles of gender, age, emotional involvement, and attachment style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(7), 871–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty JL, Davis L, & Arditti JA (2017). Cascading Resilience: Leverage Points in Promoting Parent and Child Well-Being. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(1), 111–126. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eizenman DR, Nesselroade JR, Featherman DL, & Rowe JW (1997). Intraindividual variability in perceived control in a older sample: The MacArthur successful aging studies. Psychology and aging, 12(3), 489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filosa L, Alessandri G, Robins RW, & Pastorelli C (2022). Self‐esteem development during the transition to work: A 14‐year longitudinal study from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of personality [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Lee CM, Rhew IC, Ramirez JJ, Abdallah DA, & Fairlie AM (2018). Descriptive and prospective analysis of young adult alcohol use and romantic relationships: Disentangling between-and within-person associations using monthly assessments. Substance use & misuse, 53(13), 2240–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, & Catalano RF (2010). Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: An examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. Journal of health and social behavior, 51(2), 153–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-López M, Viejo C, & Ortega-Ruiz R (2019). Well-being and romantic relationships: A systematic review in adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH, Kim JH, Wu M, & Galea S (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130, 441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, . . . Kaplan K (2004). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independentmood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and relatedconditions. Archives of general psychiatry, 61(8), 807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Colpe L, Huang L, & McKeon R (2018). National Trends in the Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Among Young Adults and Receipt of Mental Health Care Among Suicidal Young Adults. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(1), 20–27.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna KM, Kaiser KL, Brown SG, Campbell-Grossman C, Fial A, Ford A, . . . Moore TA (2018). A scoping review of transitions, stress, and adaptation among emerging adults. Advances in Nursing Science, 41(3), 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, & Rahe RH (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khubchandani J, Brey R, Kotecki J, Kleinfelder J, & Anderson J (2016). The psychometric properties of PHQ-4 depression and anxiety screening scale among college students. Archives of psychiatric nursing, 30(4), 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, & Löwe B (2009). An Ultra-Brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: The PHQ–4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(09)70864-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, . . . Brähler E (2010). A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. Journal of affective disorders, 122(1), 86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke D (2018). ggeffects: Tidy Data Frames of Marginal Effects from Regression Models. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(26), 772. doi: 10.21105/joss.00772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ludolph P, Kunzler AM, Stoffers-Winterling J, Helmreich I, & Lieb K (2019). Interventions to promote resilience in cancer patients. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 116(51–52), 865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manea L, Gilbody S, Hewitt C, North A, Plummer F, Richardson R, . . . McMillan D (2016). Identifying depression with the PHQ-2: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders, 203, 382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2015). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Materu J, Kuringe E, Nyato D, Galishi A, Mwanamsangu A, Katebalila M, . . . Wambura M (2020). The psychometric properties of PHQ-4 anxiety and depression screening scale among out of school adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC psychiatry, 20(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J. p., Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, . . . Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewton L, & Andrews G (2016). Cognitive behavioral therapy for suicidal behaviors: improving patient outcomes. Psychology research and behavior management, 9, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, & Ross CE (2003). Social causes of psychological distress: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, & Han B (2016). National Trends in the Prevalence and Treatment of Depression in Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatrics, 138(6), e20161878. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Ruth G, Eccles JS, Jacobs JE, Barber BL, & Settersten R (2005). On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. Six paths to adulthood, 320–355. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Rhew IC, Duckworth JC, Lewis MA, Abdallah DA, & Lee CM (2020). Patterns of young adult social roles transitions across 24 months and subsequent substance use and mental health. Journal of youth and adolescence, 49(4), 869–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Rhew IC, Lewis MA, Abdallah DA, Larimer ME, Schulenberg JE, & Lee CM (2018). Alcohol motivations and behaviors during months young adults experience social role transitions: Microtransitions in early adulthood. Psychology of addictive behaviors, 32(8), 895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, & Mullan JT (1981). The stress process. Journal of health and social behavior, 337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, de Kleine RA, & Smits JA (2017). Core mechanisms of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression: A review. Psychiatric Clinics of North America [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preetz R (2022). Dissolution of non-cohabiting relationships and changes in life satisfaction and mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rauer AJ, Pettit GS, Lansford JE, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2013). Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Developmental psychology, 49(11), 2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, & Maggs JL (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement(14), 54–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Sameroff AJ, & Cicchetti D (2004). The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 799–806. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404040015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr (2007). The new landscape of adult life: Road maps, signposts, and speed lines. Research in Human Development, 4(3–4), 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht J, Egloff B, & Schmukle SC (2013). Everything under control? The effects of age, gender, and education on trajectories of perceived control in a nationally representative German sample. Developmental psychology, 49(2), 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, & Wardle J (2001). Locus of control and health behaviour revisited: a multivariate analysis of young adults from 18 countries. British journal of Psychology, 92(4), 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KA, Turanovic JJ, O’Neal EN, Morse SJ, & Booth ET (2019). The cycle of violence revisited: Childhood victimization, resilience, and future violence. Journal of interpersonal violence, 34(6), 1261–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.