Abstract

Background

When gunshot and blast injuries affect only a single person, first aid can always be delivered in conformity with the relevant guidelines. In contrast, when there is a dynamic casualty situation affecting many persons, such as after a terrorist attack, treatment may need to be focused on immediately life-threatening complications.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search in Medline and on the authors’ clinical experience.

Results

In a mass-casualty event, all initial measures are directed toward the survival of the greatest possible number of patients, in accordance with the concept of “tactical abbreviated surgical care.” Typical complications such as airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, and hemorrhage must be treated within the first 10 minutes. Patients with bleeding into body cavities or from the trunk must be given priority in transport; hemorrhage from the limbs can be adequately stabilized with a tourniquet. In-hospital care must often be oriented to the principles of “damage control surgery,” with the highest priority assigned to the treatment of life-threatening conditions such as hemodynamic instability, penetrating wounds, or overt coagulopathy. The main considerations in initial surgical stabilization are control of bleeding, control of contamination and lavage, avoidance of further consequences of injury, and prevention of ischemia. Depending on the resources available, a transition can be made afterward to individualized treatment.

Conclusion

In mass-casualty events and special casualty situations, mortality can be lowered by treating immediately life-threatening complications as rapidly as possible. This includes the early identification of patients with life-threatening hemorrhage. Advance preparation for the management of a mass-casualty event is advisable so that the outcome can be as favorable as possible for all of the injured in special or tactical casualty situations.

Gunshot and blast injuries are rare occurrences in Germany. They usually result from accidents involving guns, violent crime, careless handling of explosives, or industrial accidents. Because of the low incidence, there are no robust study data on these injuries in this country. Most publications on the outcome quality of the treatment of gunshot and blast injuries are, as one would expect, retrospective cohort studies (1– 3).

The management and treatment of this class of injuries is resource-intensive and afflicted by complications (4, 5). If certain criteria are fulfilled or the clinical condition of the patients is critical, the therapeutic modus operandi according to the principles of damage control surgery (DCS), developed for the management of gunshot and blast injuries in the military context, can be recommended for the care of civilian victims (6, 7, e1). Treatment following DCS principles concentrates exclusively on survival and preservation of function, to minimize the additional (systemic) strain on the physiology of the severely injured persons (8, e2).

In the case of a mass injury event, a gun rampage, or a terror attack, departure from the standards of individual medical care may be required. There is a lack of uniform treatment recommendations in the sense of standards or guidelines for the prehospital or hospital treatment of gunshot and blast injuries, especially for major events.

Apart from the clinical trigger factors (box 1) for the adoption of the DCS strategy, the tactical situation, the number of casualties, and shortage of resources, e.g., lack of material and personnel or technical problems, may require restriction of care procedures to maximize survival under exceptional conditions.

BOX 1. Trigger factors and indications for DCS*.

Persisting hemodynamic instability

Multiple life-threatening/penetrating injuries

Severe/hemorrhagic shock

Injury severity score (ISS) >35

Persisting acidosis (pH <7.2)

Manifest coagulopathy

Hypothermia (body temperature under 35 °C)

Massive transfusion (>10 units PRBC)

Shock room thoracotomy/laparotomy required

Additional angioembolization required

Shortage of resources or mass injury event

*Modified from Parker (e17) and Asensio (34); DCS, damage control surgery; PRBC, packed red blood cells

Specialist knowledge of typical injury patterns and treatment priorities after gunshot and blast trauma is essential so that all personnel in the rescue and care chain, from first aid to primary-care hospital, are equipped to act as needed. Our intention in publishing this article is to depict the status quo with regard to the prevailing accepted principles. In the absence of evidence-based studies, our recommendations for the treatment of gunshot and blast injuries are based on our personal experience and on the findings of recent publications identified by a selective Medline survey using relevant search terms.

Initial Phase and Prehospital Care

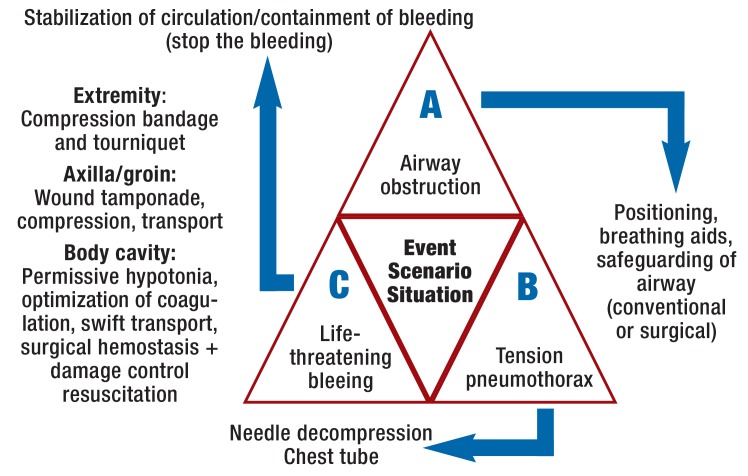

Depending on the situation, civilians with no kind of protective clothing can have injuries of any part of the body (5). In the first 10 min after injury (the “platinum 10 minutes”), the victims are in danger of the typical, avoidable immediately life-threatening complications (figure) (9). In addition, thoracoabdominal and proximal bleeding bears the highest potential for mortality and necessitates swift, targeted primary surgical care. Hemorrhage from these sites is responsible for most of the avoidable deaths from gunshot and blast injuries (10).

Figure.

Triad of immediately life-threatening complications following gunshot and blast injuries

It has been shown that care quality can be improved and immediate overall mortality reduced by following structured trauma care algorithms and uniform, standardized treatment principles (ABCDE algorithm, prehospital trauma life support [PHTLS], advanced trauma life support [ATLS]) together with communication of essential information and vital parameters using a uniform vocabulary (e3, 11).

Persons with life-threatening hemorrhage at proximal sites (axilla and groin) or in the body cavities must be identified as soon as possible.

In the short term (1 to 2 hours), bleeding from arteries of the extremities can be controlled adequately by means of a tourniquet (C-ABCDE). Bleeding from the groin or armpit is usually not sufficiently checked by wound packing or tamponade (with or without a hemostatic) and local pressure.

Active bleeding in the body cavities cannot be brought under control at the place of injury or before admission to hospital. Only swift, logistically optimized transport to a facility equipped for surgical hemostasis can reduce mortality.

Hospital treatment

When a number of patients with gunshot or blast injuries are admitted to hospital at the same time, an experienced physician, ideally one trained in rescue, catastrophe, and tactical medicine, must decide how and in what order to proceed.

In mass injury events, the priority is survival of as many victims as possible. Such an event leads to a temporary shortage of hospital resources, and in this phase individual medicine is not an option. All efforts have to be focused on treatment of the immediately life-threatening injuries (DCS together with damage-control orthopedics [DCO] and damage-control resuscitation [DCR]).

The beginning and end of this critical phase of medical care must be clearly defined and communicated and thus constitute a dynamic process (e4).

Management according to DCS principles

Management according to DCS principles should be initiated when the so-called clinical or situation-dependent trigger factors are present (box 1).

The basic principles and goals of DCS are summarized in Box 2. All efforts are directed towards swift stabilization of the pathophysiology and avoidance or treatment of the lethal triad (acidosis, coagulopathy, hypothermia).

BOX 2. Goals of initial DCS stabilization.

Stop the bleeding

Containment of contamination and lavage

Prevention of further injuries/increased complications

Ischemia prophylaxis, preservation of perfusion (or reperfusion)

DCS, damage control surgery

Simple, rapid procedures are required. Surgery to control bleeding is restricted to a minimum in order to prevent complications from organ dysfunction or protracted shock and avoid further contamination. Familiarity with the pathophysiology of gunshot and blast injuries is crucial to decision-making in such a scenario.

Pathophysiology of blast injuries

Explosive materials are divided according to the amount of energy released and the speed of the reaction into high order explosives and low order explosives. In addition, manufactured devices are distinguished from improvised explosive devices (IED) (e5). Small metal objects (nails, ball bearings) are often added to IED to increase fragmentation.

The injury pattern depends on the device used and the location. In an open space the effect decreases exponentially with increasing distance from the point of detonation, but in an enclosed area the transmitted energy is potentiated by reflection of pressure waves (4, 12, 13). Independent of these fundamental physical principles, detonation of explosives causes five types of injuries, classified as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Classification of blast injuries.

| Blast injury | Mechanism | Possible injuries |

| Primary | Barotrauma from pressure or shock wave, caused by fluctuations of atmospheric pressure in the blast wave | Eardrum rupture, injury of air-filled hollow organs (“blast lung”, bowel, etc.), air embolism, dissection and avulsion of soft tissues (12, 35, 36) |

| Secondary | Fragmentation effect: owing to their shape and their eccentric rotation, fragments travelling outward from the detonation site can produce a wound cavity 20 to 25 times larger than the fragments themselves and bring about local tissue pressure of up to 6.89 bar (e14, e18, 37). | Cause of most injuries and deaths (23):

|

| Tertiary | Collapsing buildings, impact trauma, burial; being thrown against solid objects by the blast wave also falls in this category. | After secondary injuries, tertiary injuries are the type found most frequently among primary survivors:

|

| Quaternary | Burns, inhalation trauma, exacerbation of pre-existing diseases | Burns and inhalation trauma, caused by heat or chemicals, decompensation, e.g., of pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases, complications of anticoagulant treatment |

| Quinary | Infectious, chemical, or radioactive additives to the explosives; not yet completely explained | Hyperinflammatory states at the initial stage of treatment (4, 39) |

The wound ballistics of gunshot injuries

Internal ballistics, external ballistics, and target ballistics are the key terms describing the function of guns up to the moment when the projectile exits the barrel. Detailed presentation of these concepts is outside the scope of this review. Medical interest is primarily in the effect of the projectile on its target, i.e., the wound ballistics. A multitude of factors determine exactly what happens. The factors listed in Box 3 are decisive for the amount of energy transmitted from projectile to tissues and the damage caused.

BOX 3. Factors influencing the energy transfer to tissues in gunshot injuries.

Type/construction of projectile

Distance/impact velocity

Stability of projectile in flight

Projectile caliber and weight

Tissue properties

Weapons of identical type and caliber, and also metal fragments, can cause different wounds at different distances depending on the kinetic energy on impact and the specific energy transmission to the tissues.

Treatment of typical injuries

Blast or gunshot injuries of body cavities

Penetrating thoracoabdominal injuries have a high lethal potential (14). The survival of victims of such injuries depends on swift surgical control of bleeding (12). Visible perforating foreign bodies are initially left in place because they may exert a tamponading effect. Abdominal stab wounds perforate the peritoneum in 60 to 75% of cases, but the figure for gunshot injuries is 95%, and owing to the wound ballistics of the projectile the injury patterns are complex and challenging, both diagnostically and therapeutically (15).

Explosives have by far the highest destructive potential. In the trunk, immediate direct damage to hollow or parenchymatous organs is accompanied by primary perfusion damage of the lung parenchyma and the organs. The possible delayed consequences, sometimes not arising until days later, are acute post-traumatic lung failure (acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] or blast lung) and secondary ischemic bowel perforations.

In perforating thoracic trauma, airtight closure of the entry wound without drain insertion is contraindicated, as life-threatening tension pneumothorax may result (e6). Drainage constitutes adequate treatment in 85% of perforating thoracic injuries (e7). In the event of heavy or persistent bleeding (>1500 mL initially, 500 mL/h, or >250 mL/h for >4 h), surgical intervention is recommended (e8). An overview of DCS techniques is provided in Box 4.

BOX 4. DCTS techniques*.

Swift emergency thoracotomy via anterolateral standard route (fifth intercostal space)

Nonanatomical lung resections using a stapler

“En masse“ lobectomy/pneumonectomy

All-layer closure of thoracic wall musculature

Temporary thoracic packing in presence of diffuse bleeding

Vascular interventions (ligatures/shunts, replacement)

Temporary patch closure of thoracic wall defects

Goal: Operating time 60 to max. 90 min

*Modified from Garcia et al. (40); DCTS, damage control thoracic surgery

Combined thoracoabdominal injuries are complex and associated with high mortality. A median laparotomy is created for exploration. In the event of continuing instability, exclusion of an intra-abdominal cause, and exclusion of tension pneumothorax or hemopneumothorax, transdiaphragmatic pericardial windowing is recommended (16).

Perforating abdominal injuries are generally treated by means of emergency median laparotomy. In rare selected cases nonsurgical treatment may be preferred, with intervention later if needed. Hemodynamic instability, evisceration, and peritonitis are indications for laparotomy (17).

The DCS procedures to contain bleeding and contamination in abdominal injuries are listed in Table 2. DCS often includes a laparostomy to avoid formation of an abdominal compartment. Revision or “second-look” surgery should take place 24 to 72 hours later (18). Penetrating trauma frequently involves the small and large bowel (e9).

Table 2. DCS techniques in abdominal injuries.

| Injury | Measure |

| Massive bleeding | Aortic clamping |

| Bleeding from large vessels | Ligature/bypass |

| Injury to liver parenchyma | Packing/compression |

| Bowel lesions | Staple closure/stoma/no anastomoses |

| Injuries to arteries | Shunt |

| Injuries to veins | Ligature |

| Urinary bladder injury | Catheter/drainage |

| Pancreas injury | Drainage |

| Peritoneal contamination | Lavage + laparostomy |

| Abdominal compartment | Laparostomy |

| Visceral swelling | Laparostomy |

| Goal: Operating time 60 to max. 90 min | |

DCS, Damage control surgery

After the bowel, the liver—the largest parenchymatous organ of the body—is the organ most often affected by perforating injuries, although the damage is seldom severe. Compression and application of local hemostatic agents can be primarily definitive. Resection is necessary in only 5% of liver injuries, and complex injuries are even rarer, accounting for only 2% of cases (e7).

Damage to the spleen, particularly in gunshot injuries or after blast trauma, rapidly becomes a significant hemodynamic problem. The basic decision—whether or not the spleen can be preserved—depends on the severity of injury and the patient’s hemodynamic situation. In the DCS scenario the spleen is removed. It is essential to administer the necessary vaccinations and booster injections in the course of further treatment.

Perforating injuries of the pancreas are very rare. After containment of bleeding, the further treatment depends on whether the duct system is injured (e10). While parenchymal injuries should be drained, the options for treatment of duct injuries include interventions such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), with insertion of a stent if required, and surgery ranging from debridement to resection. Primarily complex resections (head of pancreas) are associated with a poorer prognosis and represent the surgical solution of last resort (19).

If abdominal arteries are injured, in the extreme case (DCS) the celiac trunk, mesenteric artery, or internal iliac artery (unilaterally) can be ligated. Damage to the superior mesenteric artery or the renal artery, however, requires reconstruction (e11).

Under DCS conditions, every intra-abdominal vein except the portal vein can be ligated. Nevertheless, depending on the circumstances one should attempt reconstruction of high-caliber veins.

A penetrating injury of the intraperitoneal portion of the bladder should be surgically closed prior to catheter drainage. In the case of extraperitoneal bladder injuries, catheter drainage suffices. Exceptions are extraperitoneal injury of the bladder neck or perforation by objects such as foreign bodies or bone fragments, e.g., from complex pelvic fractures, that remain inside the bladder (e12).

Injuries to proximal blood vessels

The proximal blood vessels most frequently injured are the carotid artery, the subclavian artery, and the iliac artery or femoral artery. While access to the carotid artery is uncomplicated, compression of and access to the subclavian artery are more complex and may even necessitate division of the clavicle.

Access to the pelvic vascular axis can be achieved by the transabdominal or extraperitoneal route. The basic principles are control of bleeding by compression and exposure of the vessel proximal and distal to the site of injury with encircling of the vessel, and then treatment of the wound. In the context of DCS, ligature and the shunt procedure are the primary options for bridging defects of more than 2 cm. Interventional procedures for endovascular hemostasis have become standard in the absence of DCS trigger factors.

Vascular injuries of the extremities

Peripheral vascular injuries and ischemia are treated by control of bleeding, restoration of perfusion by means of locally inserted shunts, vascular bypasses, and/or fasciotomy following an ischemic event (20, 21).

If the goal is preservation of the limb, ligation of central vessels of the upper arm or thigh is contraindicated. Definitive vascular reconstruction should be achieved as swiftly as possible, ideally within 2 hours of shunt insertion. Use of an autologous vein, ideally the great saphenous vein, is recommended for vascular reconstruction after fracture stabilization (20– 23). Opinions differ regarding the timing of reconstruction, so the decision should depend on the patient’s overall status; fasciotomy is mandatory in the case of ligation (e13, 24).

Fractures of the extremities

Fractures of large tubular bones in the extremities are stabilized in the correct axial alignment by immobilization with an external fixator, extension, or a plaster cast. This repositions large fracture surfaces and contains local bleeding. Furthermore, correct axial alignment of the fractures results in relaxation or relief of the local nerves. This prevents late complications of peripheral perfusion or motor and sensory function.

Perforating soft-tissue injuries and contusions

The most frequently occurring type of injury is penetration by projectiles or fragments (25, e14). The goal is swift control of contamination to prevent secondary infection. The initial treatment comprises local irrigation with an antiseptic agent (e.g., 0.04% polyhexanide) and application of a colorless, nonadhesive antiseptic dressing. As soon as possible, depending on the situation, soft-tissue defects are then decontaminated by two rinses with large quantities of fluid and obviously avital areas of tissue are surgically debrided.

In the case of open fractures, urgent systemic antibiosis (aerobic and anaerobic spectrum, e.g., a second-generation cephalosporin with metronidazole) is indicated. Tetanus prophylaxis is mandatory.

Retrieval of embedded foreign bodies is left until later so as to minimize operating time and to avoid further soft-tissue damage. Primary wound closure is counterproductive—open treatment is the method of choice for gunshot and blast injuries of the extremities, including re-evaluation.

Following surgical revision, temporary wound coverings can be applied, e.g., negative-pressure wound therapy dressings or topical antiseptic wound gels. These have shown good results for multiresistant pathogens with regard to local cleansing and prevention of recontamination (e15, 26, 27). In the postprimary phase, local contamination is documented by microbiological examination of material harvested using swabs. Specific antibiotics are given as required (25, 26).

Burns

Up to 40% of victims of blast injuries suffer burns, either alone or in combination with other injuries. If the burns (degree IIa or worse) extend around more than two thirds of the circumference, immediate escharotomy is indicated, accompanied by fasciotomy if there is clinical suspicion of muscular compartment syndrome (e16, 28).

The patient is first washed with warm disinfectant solution (hypothermia!), then the burns are superficially debrided (removal of all loose shreds of skin and blisters) and dressed with colorless antiseptic gel (e.g., polyhexanide nitrocellulose wound gel [polyhexamethylene biguanide, PHMB]) and sterile nonadhesive gauze (e16, 28).

Compartment syndrome and fasciotomy

In compartment syndrome, which may be caused, for example, by fracture, hemorrhage, crush injury, or ischemia–reperfusion, the perfusion of the affected part of the extremity is restricted by elevated pressure in the compartment concerned. If compartment syndrome is clinically suspected, therapeutic fasciotomy must be carried out as soon as possible (29– 31). Urgent indications for fasciotomy include injury or ligation of arteries or veins in the extremities, long transport times before revascularization, crush injury, and the slightest suspicion of imminent compartment formation prior to transfer (20, 21, 23, e13).

Amputations

The difficult decision whether to preserve or amputate a limb can sometimes be postponed following adequate initial immobilization (fixator) and restoration of perfusion (e.g., shunt insertion). On the principle “life before limb,” however, an extremity may have to be sacrificed for the sake of stabilizing the patient as swiftly as possible.

If emergency amputation is necessary, the previously postulated guillotine technique should not be used. Rather, a debridement amputation should be carried out as far distal as possible and the wound should not be closed. Complete wound closure ensues a few days later under controlled conditions (21, 32, 33).

Goals of further treatment

Once the situation has been contained and the overall extent of damage is known, priority-oriented further treatment of all casualties can begin. It may be possible to return to individual medical care. Depending on the resources at hand, the casualties must be (re)distributed to the available institutions so that individualized surgical treatment can be carried out for as many of the victims as possible, or definitive treatment commenced.

The goal of the subsequent phase of restitution and stabilization is to continue and optimize the treatment that has been instituted. Measures to this end include:

Restoration of euvolemia

Normalization of ventilation parameters with correction of the acid–base balance

Optimization of perfusion and oxygenation in the periphery

Rewarming of the patient

Specific measures to optimize coagulation, adapted to the status

At an appropriate time, all objects and materials potentially relevant to investigation of the event, particularly projectiles, fragments, and clothing, should be put aside for forensic analysis.

Key Messages.

The leading cause of death in gunshot and blast injuries is hemodynamically significant bleeding.

Mortality can be reduced only by immediate emergency medical treatment of avoidable causes of death (tension pneumothorax, airway obstruction, bleeding from the extremities) and swift surgical control of hemodynamically significant bleeding from proximal vessels or in body cavities.

Operative treatment follows the principles of damage control surgery (DCS). In special situations and if resources are severely limited, management concentrates on the procedures of tactical abbreviated surgical care (TASC).

DCS focuses on surgical stabilization. Immediate treatment is restricted to life-saving procedures, with further necessary interventions ensuing over the following 24 to 72 hours.

TASC is carried out with special regard to the availability of resources according to the DCS criteria.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Bieler D, Franke AF, Hentsch S, et al. Gunshot and stab wounds in Germany—epidemiology and outcome: analysis from the TraumaRegister DGU(R)] Unfallchirurg. 2014;117:995–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00113-014-2647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulla M, Maier J, Bieler D, et al. Civilian blast injuries: an underestimated problem?: Results of a retrospective analysis of the TraumaRegister DGU. Unfallchirurg. 2016;119:843–853. doi: 10.1007/s00113-015-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stormann P, Gartner K, Wyen H, Lustenberger T, Marzi I, Wutzler S. Epidemiology and outcome of penetrating injuries in a Western European urban region. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016;42:663–669. doi: 10.1007/s00068-016-0630-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Champion HR, Holcomb JB, Young LA. Injuries from explosions: physics, biophysics, pathology, and required research focus. J Trauma. 2009;66:1468–1477. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a27e7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards DS, McMenemy L, Stapley SA, Patel HD, Clasper JC. 40 years of terrorist bombings—a meta-analysis of the casualty and injury profile. Injury. 2016;47:646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts DJ, Bobrovitz N, Zygun DA, et al. Indications for use of damage control surgery and damage control interventions in civilian trauma patients: A scoping review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:1187–1196. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb CM, MacGoey P, Navarro AP, Brooks AJ. Damage control surgery in the era of damage control resuscitation. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:242–249. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirshberg A, Mattox KL. Top knife: the art & craft of trauma surgery Shrewsbury, UK. TFM Publishing Ltd. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daban JL, Falzone E, Boutonnet M, Peigne V, Lenoir B. Wounded in action: the platinum ten minutes and the golden hour. Soins. 2014;788:14–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:S431–S437. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182755dcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarro S, Montmany S, Rebasa P, Colilles C, Pallisera A. Impact of ATLS training on preventable and potentially preventable deaths. World J Surg. 2014;38:2273–2278. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2587-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horrocks CL. Blast injuries: biophysics, pathophysiology and management principles. J Roy Army Med Corps. 2001;147:28–40. doi: 10.1136/jramc-147-01-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leibovici D, Gofrit ON, Stein M, et al. Blast injuries: bus versus open-air bombings—a comparative study of injuries in survivors of open-air versus confined-space explosions. J Trauma. 1996;41:1030–1035. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199612000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, Pons PT, Cantrill SV. Blast injuries. Lancet. 2009;374:405–415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonus C, Preuss M, Kasparek S, Nier H. Adequate management of stab and gunshot wounds. Chirurg. 2003;74:1048–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00104-003-0700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg RJ, Karamanos E, Inaba K, Okoye O, Teixeira PG, Demetriades D. The persistent diagnostic challenge of thoracoabdominal stab wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:418–423. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanei B, Mahmoudieh M, Talebzadeh H, Shahabi Shahmiri S, Aghaei Z. Do patients with penetrating abdominal stab wounds require laparotomy? Arch Trauma Res. 2013;2:21–25. doi: 10.5812/atr.6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anjaria DJ, Ullmann TM, Lavery R, Livingston DH. Management of colonic injuries in the setting of damage-control laparotomy: one shot to get it right. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:594–598. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degiannis E, Glapa M, Loukogeorgakis SP, Smith MD. Management of pancreatic trauma. Injury. 2008;39:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinck D, Gatzka F, Debus ES. Surgical combat treatment of vascular injuries to the extremities American experiences from Iraq and Afghanistan. Gefässchirurgie. 2011;16:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starnes BW, Beekley AC, Sebesta JA, Andersen CA, Rush RM Jr. Extremity vascular injuries on the battlefield: tips for surgeons deploying to war. J Trauma. 2006;60:432–442. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197628.55757.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borut LT, Acosta CJ, Tadlock LC, Dye JL, Galarneau M, Elshire CD. The use of temporary vascular shunts in military extremity wounds: a preliminary outcome analysis with 2-year follow-up. J Trauma. 2010;69:174–178. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e03e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox CJ, Gillespie DL, O‘Donnell SD, et al. Contemporary management of wartime vascular trauma. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn VY, Arthurs ZM, Herbert GS, Beekley AC, Sebesta JA. Demographics, treatment, and early outcomes in penetrating vascular combat trauma. Arch Surg. 2008;143:783–787. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.8.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramasamy A, Hill AM, Clasper J. Improvised Explosive Devices: Pathophysiology, Injury Profiles and Current Medical Management. J Roy Army Med Corps. 2009;155:265–272. doi: 10.1136/jramc-155-04-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor CJ, Hettiaratchy S, Jeffery SL, Evriviades D, Kay AR. Contemporary approaches to definitive extremity reconstruction of military wounds. J Roy Army Med Corps. 2009;155:302–307. doi: 10.1136/jramc-155-04-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dissemond J, Gerber V, Kramer A, et al. A practice-oriented recommendation for treatment of critically colonised and locally infected wounds using polihexanide. J Tissue Viability. 2010;19:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jtv.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trupkovic T, Giessler G. Burn trauma Part 1: pathophysiology, preclinical care and emergency room management. Anaesthesist. 2008;57:898–907. doi: 10.1007/s00101-008-1428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seifert J, Matthes G, Stengel D, Hinz P, Ekkernkamp A. Compartment syndrome Standards in diagnosis and treatment. Trauma und Berufskrankheit. 2002;4:101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheridan GW, Matsen FA. Fasciotomy in the treatment of the acute compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:112–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiwari A, Haq AI, Myint F, Hamilton G. Acute compartment syndromes. Br J Surg. 2002;89:397–412. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2002.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clasper JC. Amputations of the lower limb: a multidisciplinary consensus. J Roy Army Med Corps. 2007;153:172–174. doi: 10.1136/jramc-153-03-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tintle SM, Forsberg JA, Keeling JJ, Shawen SB, Potter BK. Lower extremity combat-related amputations. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2010;19:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asensio JA, McDuffie L, Petrone P, et al. Reliable variables in the exsanguinated patient which indicate damage control and predict outcome. Am J Surg. 2001;182:743–751. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DePalma RG, Burris DG, Champion HR, Hodgson MJ. Blast injuries. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1335–1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra042083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritenour AE, Baskin TW. Primary blast injury: update on diagnosis and treatment. Crit Care. 2008;36:S311–S317. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817e2a8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plurad DS. Blast injury. Mil Med. 2011;176:276–282. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnold JL, Tsai MC, Halpern P, Smithline H, Stok E, Ersoy G. Mass-casualty, terrorist bombings: epidemiological outcomes, resource utilization, and time course of emergency needs (Part I) Prehosp Disaster Med. 2003;18:220–234. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kluger Y, Nimrod A, Biderman P, Mayo A, Sorkin P. The quinary pattern of blast injury. Am J Disaster Med. 2007;2:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia A, Martinez J, Rodriguez J, et al. Damage-control techniques in the management of severe lung trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:45–50. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Perlman R, Callum J, Laflamme C, et al. A recommended early goal-directed management guideline for the prevention of hypothermia-related transfusion, morbidity, and mortality in severely injured trauma patients. Crit Care. 2016;20 doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie. S3-Leitlinie Polytrauma, Schwerverletzten-Behandlung. AWMF Register-Nr. 2016 012/019. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Mohammad A, Branicki F, Abu-Zidan FM. Educational and clinical impact of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2014;38:322–329. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Service, Médical du, RAID. Tactical emergency medicine: lessons from Paris marauding terrorist attack. Crit Care. 2016;20 doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1202-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Explosions and blast injuries: a primer for clinicians. https://archive.org/details/Explosions_and_Blast_Injuries_A_Primer_for_Clinicians_CDC (last accessed on 23 February 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E6.Wall MJ Jr., Soltero E. Damage control for thoracic injuries. Surg Clin N Am. 1997;77:863–878. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Wölfl CG, Vock B, Wentzensen A, Doll D. Stop the bleeding!—Damage control surgery vs definitive treatment. Trauma und Berufskrankheit. 2009;11:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- E8.Karmy-Jones R, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, et al. Timing of urgent thoracotomy for hemorrhage after trauma: a multicenter study. Arch Surg. 2001;136:513–518. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Nicholas JM, Rix EP, Easley KA, et al. Changing patterns in the management of penetrating abdominal trauma: the more things change, the more they stay the same. J Trauma. 2003;55:1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000101067.52018.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Aucar JA, Losanoff JE. Primary repair of blunt pancreatic transection. Injury. 2004;35:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(03)00164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Müller T, Doll D, Kliebe F, Ruchholtz S, Kühne C. Damage Control bei hämodynamisch instabilen Patienten - Eine Behandlungsstrategie für Schwerverletzte. Anästhesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2010;45:626–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Corriere JN Jr., Sandler CM. Management of the ruptured bladder: seven years of experience with 111 cases. J Trauma. 1986;26:830–838. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Quan RW, Gillespie DL, Stuart RP, Chang AS, Whittaker DR, Fox CJ. The effect of vein repair on the risk of venous thromboembolic events: a review of more than 100 traumatic military venous injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Weil YA, Mosheiff R, Liebergall M. Blast and penetrating fragment injuries to the extremities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:S136–S139. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200600001-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Machen S. Management of traumatic war wounds using vacuum-assisted closure dressings in an austere environment. US Army Med Dep J. 2007:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Giessler GA, Deb R, Germann G, Sauerbier M. Primary treatment of burn patients. Chirurg. 2004;75:560–567. doi: 10.1007/s00104-004-0863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Parker P. Consensus statement on decision making in junctional trauma care. J Roy Army Med Corps. 2011;157:S293–S295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Born CT. Blast trauma: the fourth weapon of mass destruction. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:279–285. doi: 10.1177/145749690509400406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]