Abstract

In order to recapitulate the best available evidence of milk consumption and multiple health-related outcomes, we performed an umbrella review of meta-analyses and systematic reviews in humans. Totally, 41 meta-analyses with 45 unique health outcomes were included. Milk consumption was more often related to benefits than harm to a sequence of health-related outcomes. Dose–response analyses indicated that an increment of 200 ml (approximately 1 cup) milk intake per day was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension, colorectal cancer, metabolic syndrome, obesity and osteoporosis. Beneficial associations were also found for type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer's disease. Conversely, milk intake might be associated with higher risk of prostate cancer, Parkinson’s disease, acne and Fe-deficiency anaemia in infancy. Potential allergy or lactose intolerance need for caution. Milk consumption does more good than harm for human health in this umbrella review. Our results support milk consumption as part of a healthy diet. More well-designed randomized controlled trials are warranted.

Keywords: Milk, Health, Umbrella review, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Introduction

Milk (Lac), which was used by human in the early of the seventh millennium BC [1, 2], is a nutritious, white liquid food secreted by the mammary glands of mammals. Cows' milk consumption varies around the world, with an average of 10–212 kg per person per year [3]. Milk contains 18 of 22 essential nutrients [4], including a various of bioactive peptides and fatty acids such as caseins, whey proteins, milk polar lipids (MPL), α-linolenic acid (ALA), conjugated linoleic acids (CLA), palmitic acid (16:0), lactose and other minor constituents (ie, calcium, phosphorous, magnesium, and vitamin D) which have an important impact on human metabolism and health [5, 6]. Evidence showed that milk has a wide range of physiological functionalities including anti-carcinogenic [7], anti-inflammatory [8], anti-oxidative [9], anti-adipogenic [10], anti-hypertensive [11], anti-hyperglycemia [12], and anti-osteoporosis [13]. Milk has been not only the primary source of nutrition for any newborn in mammalian species, but also an excellent source of the nutrients for children's growth and most adults, which has been recommended by the great amount of dietary guidelines all over the world [14, 15]. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines put forward that adults should intake three servings of dairy daily [16]. And the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020 for adults recommend the equivalent of three cups a day of fat-free milk [17].

The association of milk consumption and a sequence of health outcomes has been examined widely. However, the conclusions were inconsistent among different studies in humans [18–20]. In view of the importance of milk in our diet, it is crucial to consistently assess the totality of large amounts of data on the effects of milk intake on all health-related outcomes. Umbrella reviews could provide the highest quality of evidence, if performed and interpreted properly [21]. Thus, we conducted an umbrella review by integrating evidence from multiple meta-analyses to roughly generalize the advantages and disadvantages of milk consumption [22]. This way can help to determine the extent and magnitude of the connection of milk intake and different health outcomes, and more importantly, to evaluate the results of existing evidence for any risks that associated with increased milk consumption before an interventional trial was performed. And the results can provide the evidence which can be used to develop or renew dietary guidelines for decision makers.

Methods

Umbrella review methods

An umbrella review is the summary of existing systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses, which can present important information that can be used by decision makers in health care to systematically understand a topic area [23–25].

Literature research

We search PubMed, Embase and Web of Science from the beginning to April 16, 2019 to identify the systematic reviews with meta-analyses of observational or interventional study that researched the connection of milk intake and multiple health-related outcomes. The following research strategy was used to conduct the literature retrieve: (milk OR dairy) AND (systematic review* OR meta-analys*), using truncated terminology for all areas. The reference lists of eligible papers and relevant clinical guidelines were also searched. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or discussion with the third researcher.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the article was a meta-analysis with/without systematic review of interventional and/or observational studies; (2) evaluated the association of milk consumption and health outcomes; (3) reported effect sizes: odds ratio (OR), relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) for qualitative outcomes and mean difference (MD) or standardized mean differences (SMD) for quantitative outcomes; (4) published in English. If there were more than one similar article, only the newest and larger one was included. The exclusion criteria were: (1) systematic reviews without meta-analyses; (2) data from animal or in vitro; (3) on dairy products.

Data extraction

The processes of data extraction were performed by two authors independently. For individual eligible meta-analysis, the following information were extracted: first author, year, publication of journal, outcomes of interest, numbers of study and the type of milk. Then we extracted the amount of studies (which mean the number of study in the single meta-analysis included in our review), study designs (case–control, cohort, or randomized controlled trial [RCT]), and the number of cases and control/total participants. In addition, we abstracted data including metric (OR, RR, HR, MD, SMD), the summary estimates and related 95% confidence intervals (CI), heterogeneity (I2), fixed or random effect model was used in particular meta-analysis, and publication bias was recorded as well. If there were more than one outcome was reported in one article, we extracted each outcome respectively. If any discrepancies that were unable to be solved by consensus would be resolved by a third author, who made the final decision.

Assessment of methodological quality and quality of evidence of included studies

The revised AMSTAR/AMSTAR 2 was used to assess the methodological quality of each involved meta-analysis, which was a trustworthy and well-founded measurement tool to estimate the levels of systematic reviews and meta-analysis for randomized and non-randomized studies [26]. The AMSTAR 2 was composed of 16 items including 7 critical domains and grades the overall confidence of each review as “high”, “moderate”, “low” and “critically low” based on detailed and specific explanations of bias. We used the GRADE system to assess the quality of data for included articles [27], which assorted the quality of data into four grade that “high”, “moderate”, “low”, and “very low”. Based on RCTs or observational studies, the grade of evidence can be decreased or increased according to the risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and magnitude of effect [28].

Method of analysis

We extracted summary estimates and 95% CI of each related outcome, which was calculated by both fixed and inverse variance random effects methods. We extracted the I2 metric and Egger’s test to measure the heterogeneity and publication bias if they were available. And if the number of studies included in the meta-analyses was more than ten, we would calculate the publication bias through Egger`s regression test with the detailed original data were obtainable. A P < 0.1 for Egger`s regression test was regarded as the statistically significant publication bias. If the total estimate effects were not reported, we chose the outcomes derived from cohort rather than case–control or cross-sectional studies due to the quality of study. In dose–response analysis, the category of one serving or one glass of milk was equal to 244 g [29]. We did not reanalyze the other data or primary studied included in the meta-analysis.

Results

Characteristics of meta-analyses

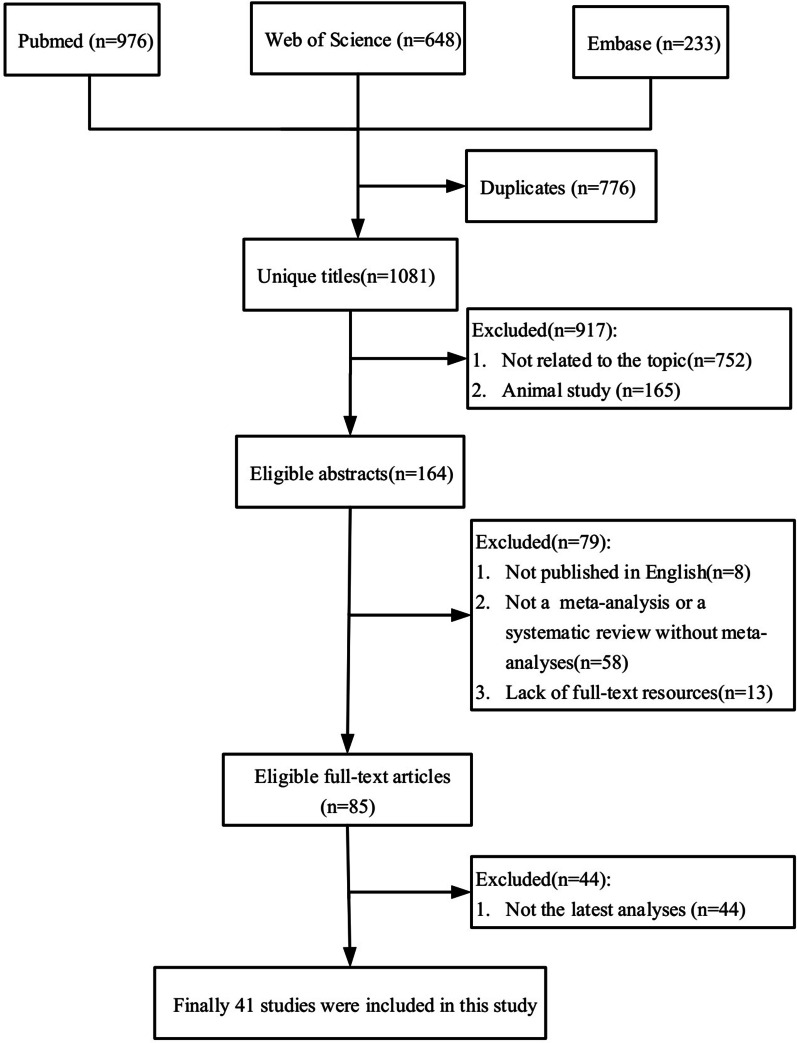

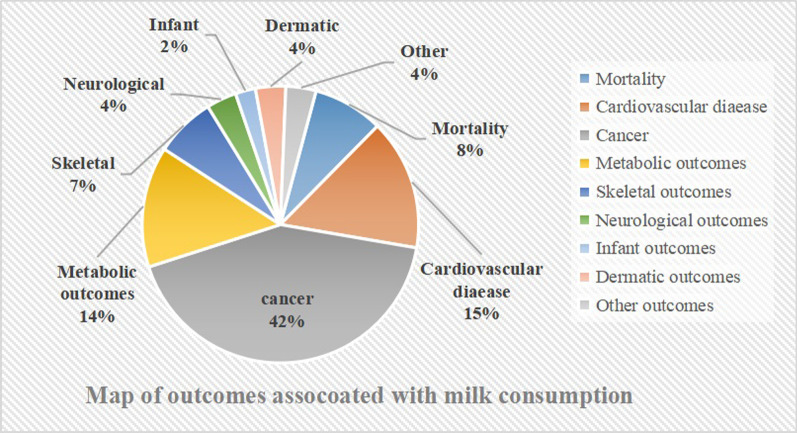

Figure 1 showed the processes of systematic search and results of eligible studies. Totally, 1857 articles were retrieved and 85 meta-analyses were eligible. Finally, forty-one most recent meta-analyses with 45 unique outcomes were included in our umbrella review (Fig. 2). The number of meta-analysis for single outcome ranged from one to seven and with a median number of two. The associations between milk intake and cancer outcomes were presented in Table 1. The relation of milk intake to mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes were shown in Table 2. And other outcomes related to milk consumption were shown in Table 3. The results of AMSTAR 2 and GRADE were shown in Table 4. Full versions of summary estimates which investigated the association between milk intake and all health-related outcomes were available in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection process

Fig. 2.

Map of outcomes associated with milk consumption

Table 1.

Associations between milk consumption and cancer outcomes

| Outcomes | First author | Year | Types of milk | No. of studies in MA | Type of studies in MA | No. of cases/total | Effects mode | Metric of MA | Effect size | 95% CI | I2% | Publication bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant associations | ||||||||||||

| Most beneficial | ||||||||||||

| Colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Low-fat milk | 2 | Cohort | 3339/15,441 | Fixed | RR | 0.73 | 0.61–0.87 | 0 | NA |

| Distal colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 40,651/15,657 | Fixed | RR | 0.75 | 0.63–0.90 | 25 | NA |

| CRC | Barrubes | 2019 | Low-fat milk | 2 | Cohort | 3507/484,338 | Fixed | RR | 0.76 | 0.66–0.88 | 42 | NA |

| Colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 8 | Cohort | 3339/15,441 | Random | RR | 0.79 | 0.72–0.87 | 0 | NA |

| Proximal colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 40,651/15,657 | Fixed | RR | 0.81 | 0.68–0.96 | 0 | NA |

| CRC | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 9 | Cohort | 9118/1,003,303 | Random | RR | 0.82 | 0.76–0.88 | 2 | NA |

| Rectal cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 5 | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 0.84 | 0.73–0.97 | 0 | NA |

| Colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 3339/15,441 | Fixed | RRa | 0.88 | 0.84–0.93 | 0 | NA |

| Bladder Cancer | Bermejo | 2019 | Milk | 14 | Cohort/case control | NA/438,319 | Random | RR | 0.89 | 0.81–0.98 | 66.4 | 0.269 |

| CRC | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 9 | Cohort | 9118/1,003,303 | Random | RRb | 0.90 | 0.86–0.93 | 0 | NA |

| Rectal cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | NA | Fixed | RRc | 0.91 | 0.84–0.97 | 25 | NA |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Milk | 8 | Cohort | 19,664/448,719 | Random | RR | 0.92 | 0.85–0.99 | 0 | No |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Skim milk | 8 | Cohort | 16,664/586,726 | Random | RR | 0.93 | 0.85–1.00 | 40.1 | 0.616 |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Skim milk | 5 | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 0.96 | 0.92–1.00 | 11.9 | 0.498 |

| Most harmful | ||||||||||||

| DLBCL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 3 | Case–control | 352/NA | Random | RR | 1.49 | 1.08–2.06 | 8.9 | NA |

| Gastric cancr | Wang | 2018 | Milk | 21 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RR | 1.44 | 1.15–1.81 | 82.7 | NA |

| NHL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 14 | Cohort/case control | 7109/NA | Random | RR | 1.41 | 1.08–1.84 | 88.6 | no |

| Ovarian cancer | Liu | 2015 | Milk | 11 | Cohort | NA | Random | OR | 1.23 | 1.03–1.46 | > 50 | 0.957 |

| Bladder Cancer | Bermejo | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort/case control | NA/3933 | Random | RR | 1.21 | 1.04–1.38 | 86.1 | NA |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Low-fat milk | 6 | Cohort | 19,430/432,943 | Random | RRd | 1.14 | 1.05–1.25 | 51 | NA |

| NHL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 3739/NA | Random | RRe | 1.13 | 1.00–1.28 | NA | NA |

| NHL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 3739/NA | Random | RRf | 1.12 | 1.00–1.26 | NA | NA |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Milk | 14 | Cohort | 11,392/566,146 | Random | RR | 1.11 | 1.03–1.21 | 21 | no |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Low-fat milk | 5 | Cohort | NA/374,664 | Random | RRg | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | 67 | NA |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Milk | 13 | Cohort | NA/559,383 | Random | RRg | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 9 | NA |

| Non-significant associations | ||||||||||||

| Distal colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 2 | Cohort | 40,651/15,657 | Fixed | RR | 0.78 | 0.60–1.01 | 0 | NA |

| Breast cancer | Chen | 2019 | Low-fat milk | 3 | Case–control | NA | Random | OR | 0.85 | 0.70–1.04 | < 50 | 0.583 |

| Colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 2 | Cohort | 3339/15,441 | Fixed | RR | 0.87 | 0.72–1.05 | 0 | NA |

| Pancreatic cancer | Genkinger | 2014 | Low-fat milk | 14 | Cohort | 307/NA | Random | HR | 0.87 | 0.75–1.01 | 5 | NA |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 18 | Cohort | 19,747/775,778 | Random | RR | 0.92 | 0.84–1.02 | 53.5 | 0.292 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Genkinger | 2014 | Milk | 14 | Cohort | 373/NA | Random | HR | 0.92 | 0.77–1.10 | 0 | NA |

| Ovarian cancer | Liu | 2015 | Low-fat/skim milk | 13 | Cohort | NA | Random | OR | 0.93 | 0.79–1.09 | < 50 | 0.370 |

| ESCC | Li | 2016 | Milk | 11 | Case–control | 2311/NA | Random | RR | 0.93 | 0.74–1.16 | 52.9 | 0.960 |

| Rectal cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 2 | Cohort | NA | Fixed | RR | 0.94 | 0.76–1.16 | 0 | NA |

| Breast cancer | Chen | 2019 | Milk | 8 | Case–control | NA | Random | OR | 0.95 | 0.80–1.13 | < 50 | 0.272 |

| CRC | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 5198/545,046 | Fixed | RR | 0.97 | 0.86–1.09 | 40 | NA |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 11 | Cohort | NA | Random | RRg | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 36.4 | 0.355 |

| ESCC | Li | 2016 | Milk | 6 | Case–control | NA | Random | RRb | 0.97 | 0.70–1.35 | 58.9 | NA |

| Lung cancer | Yang | 2016 | Low-fat milk | 3 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RR | 0.98 | 0.69–1.41 | 0 | 0.120 |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Milk | 6 | Cohort | NA/388,664 | Random | RRg | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0 | NA |

| NHL | Sergentanis | 2019 | Milk | 4 | Cohort | 1517/NA | Random | RR | 0.99 | 0.85–1.15 | 0 | 0.461 |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 9 | Cohort | 13,781/554,775 | Random | RR | 0.99 | 0.87–1.12 | 37.4 | 0.723 |

| Endometrial cancer | Li | 2017 | Milk | 6 | Cohort/case control | 3538/331,168 | Random | OR | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0 | NA |

| FL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 3 | Case–control | 390/NA | Random | RR | 0.99 | 0.47–2.07 | 89.8 | NA |

| Pancreatic cancer | Genkinger | 2014 | Milk | 14 | Cohort | 145/NA | Random | HR | 1.01 | 0.83–1.22 | 0 | NA |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 5 | Cohort | NA | Random | RRg | 1.02 | 0.92–1.13 | 32.8 | 0.660 |

| NHL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 3739/NA | Random | RRh | 1.04 | 0.97–1.12 | NA | NA |

| SLL/CLL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 3 | Case–control | 477/NA | Random | RR | 1.04 | 0.69–1.55 | 44.1 | NA |

| NHL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 3739/NA | Random | RRi | 1.07 | 0.96–1.19 | NA | NA |

| Lung cancer | Yang | 2016 | Milk | 22 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RR | 1.08 | 0.80–1.46 | 90.5 | 0.300 |

| NHL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 3739/NA | Random | RRj | 1.11 | 0.99–1.24 | NA | NA |

| HCC | Yang | 2017 | Milk | 7 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RR | 1.13 | 0.67–1.88 | 78 | > 0.1 |

| Proximal colon cancer | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | 2 | Cohort | 40,651/15,657 | Fixed | RR | 1.20 | 0.96–1.49 | 83 | NA |

MA meta-analysis, CI confidence interval, RR risk ratio, HR hazard ratio, OR odds ratio, NHL non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC colorectal cancer, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, FL follicular lymphoma, SLL/CLL small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, ESCC esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, NA not available

a488 g/day; b244 g/day; c732 g/day; dhighest verse lowest; e200 g/day; f440 g/day; g490 g/day; h120 g/day; i210 g/day; j370 g/day

Table 2.

Association between milk consumption and mortality and cardiovascular disease

| Outcomes | First author | Year | Types | No. of studies in MA | Type of studies in MA | No. of cases/total | Effects mode | Metric of MA | Effect size | 95% CI | I2% | Publication bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ||||||||||||

| Significant associations | ||||||||||||

| CHD mortality | Mazidi | 2018 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 18,927/105,528 | Random | RR | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | 10.4 | NA |

| PC mortality | Lu | 2016 | Milk | NA | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 1.50 | 1.03–2.17 | NA | NA |

| PC mortality | Lu | 2016 | Milk | NA | Cohort | NA | Random | RRa | 1.43 | 1.13–1.81 | NA | NA |

| Non-significant associations | ||||||||||||

| CVD mortality | O'Sullivan | 2013 | Milk | 7 | Cohort | 17,455/338,421 | Random | RR | 0.96 | 0.81–1.13 | 22.8 | NA |

| All-cancer mortality | Lu | 2016 | Milk | NA | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 0.97 | 0.92–1.03 | 8.4 | 0.95 |

| All-cause mortality | Mazidi | 2018 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 23,324/63,390 | Random | RR | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 8.3 | NA |

| PC mortality | Lu | 2016 | Skim/low-fat milk | NA | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 1.00 | 0.75–1.33 | NA | NA |

| Total mortality | Mullie | 2016 | Milk | 11 | Cohort | 63,545/281,788 | Random | RRa | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 94 | 0.64 |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Significant associations | ||||||||||||

| Stroke | de Goede | 2016 | Milk | 14 | Cohort | 25,269/603,920 | Random | RRb | 0.93 | 0.88–0.98 | 86 | 0.06 |

| CVD | Soedamah-M | 2011 | Milk | 4 | Cohort | 2283/13,518 | Random | RRb | 0.94 | 0.89–0.99 | 0 | NA |

| Hypertension | Soedamah-M | 2012 | Milk | 7 | Cohort | 14,398/47,647 | Random | RRb | 0.96 | 0.94–0.98 | NA | NA |

| Stroke | de Goede | 2016 | High-fat milk | 4 | Cohort | 5942/159,547 | Random | RRb | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | 0 | NA |

| Non-significant associations | ||||||||||||

| Arterial Stiffness | Diez-F | 2019 | Milk | 4 | Cross-sectional | NA/15,553 | Random | NA | 0.02 | -0.01–0.05 | 0 | NA |

| Stroke | Gholami | 2017 | Milk | 10 | Cohort | 22,946/440,397 | Random | RR | 0.91 | 0.81–1.01 | 71.4 | 0.45 |

| Stroke | de Goede | 2016 | Low-fat milk | 4 | Cohort | 5942/159,547 | Random | RRb | 0.96 | 0.90–1.03 | 68.2 | NA |

| CVD | Guo | 2017 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 21,580/249,779 | Random | RR | 1.01 | 0.93–1.10 | 92.4 | No |

| CHD | Gholami | 2017 | Milk | 9 | Cohort | 4866/212,767 | Random | RR | 1.05 | 0.96–1.15 | 0 | 0.6 |

MA meta-analysis, No. number, CI confidence interval, RR risk ratio, CHD coronary heart disease, PC prostate cancer, CVD cardiovascular disease, NA not available

a244 g/day; b200 g/day

Table 3.

Association between milk consumption and metabolic, skeletal, cognitive, infant and other outcomes

| Outcomes | First author | Year | Types | No. of studies in MA | Type of studies in MA | No. of cases/total | Effects mode | Metric of MA | Effect size | 95% CI | I2% | Publication bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant associations | ||||||||||||

| Most beneficial | ||||||||||||

| Osteoporosis | Malmir | 2019 | Milk | 6 | Cohort | NA | Random | RRa | 0.61 | 0.50–0.75 | NA | no |

| Alzheimer's disease | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 2 | Cohort | 417/NA | Random | OR | 0.63 | 0.44–0.90 | 0.0 | NA |

| Cognitive Disorders | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 5 | Cohort/cross-sectional | 1273/NA | Random | OR | 0.72 | 0.56–0.93 | 64.0 | NA |

| Metabolic syndrome | Mena | 2019 | Milk | 5 | Cohort | 4065/15,657 | Random | RR | 0.79 | 0.64–0.97 | 66.0 | NA |

| Obesity | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 16 | Cohort/cross-sectional | NA | Random | OR | 0.81 | 0.75–0.88 | 62.1 | 0.109 |

| Obesity | Wang | 2016 | Milk | 4 | Cohort/cross-sectional | NA | Random | ORa | 0.84 | 0.77–0.92 | NA | NA |

| Metabolic syndrome | Lee | 2018 | Milk | 9 | Cohort/case control | 7002/29,077 | Random | RRa | 0.87 | 0.79–0.95 | 44.7 | 0.2 |

| T2DM | Tian | 2017 | Milk | 7 | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 0.87 | 0.78–0.96 | 52.2 | 0.67 |

| Abdominal obesity | Lee | 2018 | Milk | 7 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RRa | 0.88 | 0.79–0.97 | 56.8 | NA |

| HTG | Lee | 2018 | Milk | 4 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RRb | 0.90 | 0.81–0.98 | 0.0 | NA |

| Most harmful | ||||||||||||

| FDA | Griebler | 2016 | Milk | 4 | RCT/cohort | NA/1683 | Random | RR | 3.67 | 2.73–5.19 | 0.0 | NA |

| Acne | Aghasi | 2019 | Milk | 8 | Cohort/case control/cross-sectional | 3102/19,376 | Fixed | OR | 1.48 | 1.31–1.66 | 23.6 | 0.17 |

| PD | Jiang | 2014 | Milk | 5 | Cohort | 873/304,193 | Random | RRb | 1.45 | 1.23–1.73 | 16.1 | 0.62 |

| Acne | Juhl | 2018 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 7856/53,214 | Random | ORc | 1.41 | 1.05–1.90 | NA | NA |

| PD | Jiang | 2014 | Milk | 4 | Cohort | 785/278,786 | Random | RRa | 1.17 | 1.06–1.30 | NA | NA |

| Hip fracture | Malmir | 2019 | Milk | 8 | Cohort | NA | Random | RRa | 1.09 | 1.07–1.11 | NA | 0.015 |

| Non-significant associations | ||||||||||||

| Dental erosion | Li | 2012 | Milk | 4 | Cohort | NA/3387 | Random | OR | 0.67 | 0.11–4.01 | NA | NA |

| Dementia | Wu | 2016 | Milk | 3 | Cohort/cross-sectional | 552/NA | Random | OR | 0.70 | 0.48–1.02 | 18.0 | NA |

| Osteoporosis | Malmir | 2019 | Milk | 6 | Cohort/case control/cross-sectional | NA | Random | RR | 0.79 | 0.57–1.08 | 63.3 | no |

| Vertebral fracture | Matia | 2019 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | NA/15,295 | Random | HR | 0.81 | 0.66–1.00 | 0.0 | 0.068 |

| HDL-C | Lee | 2018 | Milk | 4 | Cohort/case control | NA | Random | RRb | 0.89 | 0.75–1.04 | 72.8 | NA |

| Endometriosis | Hoorsan | 2017 | Milk | 2 | Cohort/case control | 1862/69,702 | Random | OR | 0.90 | 0.65–1.23 | 81.2 | 0.32 |

| Hip fracture | Malmir | 2019 | Milk | 10 | Cohort | NA | Random | RR | 0.93 | 0.75–1.15 | 86.7 | 0.015 |

| T2DM | Gijsbers | 2016 | Milk | 11 | Cohort | 17,241/145,472 | Random | RRa | 0.97 | 0.93–1.02 | 57.0 | 0.07 |

| T2DM | Gijsbers | 2016 | High-fat milk | 9 | Cohort | 267,588/336,061 | Random | RRa | 0.99 | 0.88–1.11 | 84.0 | 0.78 |

| T2DM | Gijsbers | 2016 | Low-fat milk | 7 | Cohort | 200,981/267,588 | Random | RRa | 1.01 | 0.97–1.05 | 72.0 | NA |

| Cognitive function | Lee | 2018 | Milk | 3 | Cohort | 714/5460 | Random | RR | 1.21 | 0.81–1.82 | 64.1 | NA |

MA meta-analysis, CI confidence interval, RR risk ratio, OR odds ratio, HR hazard ratio, MD mean difference, PD Parkinson’s disease, FDA Fe-deficiency anaemia, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, HTG hypertriacylglycerolaemia, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, NA not available

a200 g/day; bhighest versus lowest; c≤ 1 glass/week versus 1 glass/day

Table 4.

Assessments of AMSTAR 2 scores and GRADE classification

| Outcomes | First author | Year | Types | AMSTAR 2 | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | |||||

| All-cause mortality | Mazidi | 2018 | Milk | Moderate | Low |

| CHD mortality | Mazidi | 2018 | Milk | Moderate | Low |

| All cancer mortality | Lu | 2016 | Milk | High | Low |

| Prostate cancer mortality | Lu | 2016 | Milk | High | Very low |

| Prostate cancer mortality | Lu | 2016 | Skim/low-fat milk | High | Very low |

| Cancer | |||||

| CRC | Barrubes | 2019 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| CRC | Barrubes | 2019 | Low-fat milk | Low | Low |

| Prostate cancer | Aune | 2015 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| DLBCL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | Critically low | Low |

| Gastric cancr | Wang | 2018 | Milk | Critically low | Moderate |

| Bladder Cancer | Bermejo | 2019 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bladder Cancer | Bermejo | 2019 | Whole milk | Moderate | Low |

| Breast cancer | Chen | 2019 | Low-fat milk | Critically low | Very low |

| Breast cancer | Chen | 2019 | Milk | Critically low | Low |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Breast cancer | Wu | 2016 | Skim milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Endometrial cancer | Li | 2017 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| ESCC | Li | 2016 | Milk | High | Moderate |

| FL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | Critically low | Very low |

| HCC | Yang | 2017 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| Lung cancer | Yang | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Lung cancer | Yang | 2016 | Low-fat milk | Moderate | Low |

| NHL | Sergentanis | 2019 | Milk | Low | Low |

| Ovarian cancer | Liu | 2015 | Low-fat/skim milk | Critically low | Low |

| Ovarian cancer | Liu | 2015 | Milk | Critically low | Moderate |

| Pancreatic cancer | Genkinger | 2014 | Milk | Critically low | Moderate |

| Pancreatic cancer | Genkinger | 2014 | Whole milk | Critically low | Moderate |

| Pancreatic cancer | Genkinger | 2014 | Low-fat milk | Critically low | Moderate |

| SLL/CLL | Wang | 2016 | Milk | Critically low | Very low |

| Cardiovascular outcomes | |||||

| CVD | Guo | 2017 | Milk | High | Low |

| CVD | Soedamah-Muthu | 2011 | Milk | Low | Low |

| CHD | Gholami | 2017 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Arterial Stiffness | Diez-Fernandez | 2019 | Milk | High | Moderate |

| Hypertension | Soedamah-Muthu | 2012 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| Stroke | de Goede | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Stroke | de Goede | 2016 | High-fat milk | Moderate | Low |

| Stroke | de Goede | 2016 | Low-fat milk | Moderate | Low |

| Stroke | Gholami | 2017 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Metabolic outcomes | |||||

| Abdominal obesity | Lee | 2018 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| T2DM | Gijsbers | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Low |

| T2DM | Gijsbers | 2016 | Low-fat milk | Moderate | Low |

| T2DM | Gijsbers | 2016 | High-fat milk | Moderate | Low |

| Hypertriacylglycerolaemia | Lee | 2018 | Milk | Moderate | Low |

| Metabolic Syndrome | Mena | 2019 | Milk | Critically low | Moderate |

| Metabolic Syndrome | Lee | 2018 | Milk | Moderate | Moderate |

| Obesity | Wang | 2016 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| T2DM | Tian | 2017 | Whole milk | Low | Low |

| Skeletal outcomes | |||||

| Hip fracture | Malmir | 2019 | Milk | Low | Low |

| Osteoporosis | Malmir | 2019 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| Vertebral fracture | Matia | 2019 | Milk | Low | Very low |

| Neurological outcomes | |||||

| Alzheimer's disease | Wu | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Very low |

| Cognitive Disorders | Wu | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Low |

| Cognitive function | Lee | 2018 | Milk | Moderate | Very low |

| Parkinson’s disease | Jiang | 2014 | Milk | Low | Low |

| Dementia | Wu | 2016 | Milk | Moderate | Very low |

| Infant outcomes | |||||

| FDA | Griebler | 2016 | Milk | Low | Low |

| T1DM | Griebler | 2016 | Milk | Low | Low |

| Other outcomes | |||||

| Acne | Aghasi | 2019 | Milk | Low | Moderate |

| Dental erosion | Li | 2012 | Milk | Critically low | Very low |

| Endometriosis | Hoorsan | 2017 | Milk | Low | Very low |

AMSTAR a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews, GRADE Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation, CVD cardiovascular disease, CHD coronary heart disease, CRC colorectal cancer, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, ESCC esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, FL follicular lymphoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, NHL non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, SLL/CLL small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, FDA Fe-deficiency anaemia, T1DM type 1 diabetes mellitus

Mortality

Milk consumption was not connected with total mortality [30], CVD mortality [31] or all-cancer mortality [32], while it was associated with a elevated risk of mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) (1.04; 1.02–1.06) [30] and prostate cancer (1.50; 1.03–2.17) [32].

Cardiovascular disease

Although high verse low milk consumption was not related to the risk of CVD, CHD and stroke [33, 34], dose–response analysis manifested a 7% lower risk of stroke (0.93; 0.88–0.98) [35], a 6% lower risk of CVD (0.94; 0.89–0.99) [36], and a 4% lower risk of hypertension (0.96; 0.94–0.98) [37] with increment of 200 ml milk consumption per day. However, high-fat milk intake was connected with a 4% higher risk of stroke (1.04; 1.02–1.06) [35].

Cancer outcomes

High milk intake was consistently related to decreased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) (0.82, 0.76–0.88) [38]. The meta-analysis with 1,003,303 subjects showed that the highest milk intake was connected with a lower risk of both colon and rectal cancer, especially in colon cancer (0.79; 0.72–0.87) [38]. However, the effects depend on the types of milk. Low-fat milk consumption was significantly related to decreased risk of CRC. Dose–response analysis showed that there was a significant linear association and per 1 serving increment of total milk was connected with a 10% lower risk of CRC [38].

Conversely, compared with low milk consumption, high consumption were related to increasing risk of prostate cancer (1.11; 1.03–1.21) [39], diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [40] and gastric cancer [41]. A 200 g/day milk consumption was connected with increasing risk of prostate cancer and the summary relative risk was 1.03 (95% CI 1.00–1.06; P = 0.04) [39].

The effects were inconsistent for bladder cancer [42], breast cancer [43], ovarian cancer [44] and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [40] because of the different type or dose of milk. No association was found between milk consumption and endometrial cancer [45], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [46], hepatocellular carcinoma [47], lung cancer [48], follicular lymphoma [40], small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia [40] and pancreatic cancer [49].

Metabolic outcomes

Higher milk intake was contrarily related to the T2DM risk (0.87; 0.78–0.96) [50], metabolic syndrome (0.79; 0.64–0.97) [51] and obesity (0.81; 0.75–0.88) [52]. Dose–response analysis suggested that the 200 g/day increment of milk was related to a 13% lower risk of metabolic syndrome [53] and a 16% lower risk of obesity [52].

Skeletal outcomes

Milk consumption was not related to the risk of hip fracture [54] while every additional 200 g/day milk consumption was connected with a 39% lower risk of osteoporosis (0.61; 0.50–0.75) [55].

Neurological outcomes

High milk intake was connected with a decreased risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (0.63; 0.44–0.90) [56], but it was connected with the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (1.45; 1.23–1.73) [57]. Linear dose–response relationship manifested that PD risk would be increased by 17% for every 200 g/day per day increase in milk consumption [57].

Infant outcomes

High milk consumption was related to an elevated risk of developing Fe-deficiency anaemia (3.67; 2.73–5.19) [58] but not of type 1 diabetes mellitus [58] in infancy.

Other outcomes

Milk intake was positively connected with the increased risk of acne (1.48; 1.31–1.66) [59] but not with endometriosis [60] or dental erosion [61].

Side effects

The prevalence of cow's milk allergy was 0.6–3.0% by sensitization tests or challenge confirmed allergy [62, 63]. Immunotherapy is promising (in terms of acquiring desensitization) but data are insufficient to recommend use [63–65]. Lactose intolerance is a real and important clinical syndrome [66, 67], its prevalence is 0–17.9% [68]. However, most person with presumed lactose intolerance or malabsorption can tolerate 12–15 g of lactose (roughly 1 cup of milk) [67, 69].

Heterogeneity of included studies

In the all included studies, about 37.8% studies had a lower heterogeneity with I2 < 25%; about 31.6% studies had a moderated heterogeneity, the I2 between 25 and 75%; and 14.3% studies had a high heterogeneity with I2 > 75%. However, there were 16.3% studies did not reported the heterogeneity and we cannot re-analysis because of the unavailable information.

Publication bias of included studies

The funnel plots and Egger’s test were used in this umbrella. About 31.6% studies reported there were no publication biases while 5 report significant evidence for publication biases including stroke, hip fracture, vertebral fracture and diabetes [70]. The others meta-analysis did not reported the outcomes of publication bias owe to the insufficient number of studies. However, it was very possible that unreported publication bias existed in many of the included studies.

AMSTAR 2 and GRADE classification of included studies

The results of AMSTAR 2 of the included studies were shown in Table 4. The studies were rated as four levels, and 11.1% were rated as “high”, about 30.6% were rated as “moderate”, about 38.9% were rated as “low” and 19.4% were classified into “critically low”. And the reason was that most of studies failed to report the funding sources of the studies included in the meta-analysis (item 10). The detailed results of each item of AMSTAR 2 for the included meta-analysis were available in Additional file 2: Table S2. As for the quality of outcomes, about 18.4% were graded as “very low”, forty percent were graded as “low” and 41.6% were graded as “moderate”. None one was stratified as “high” because the meta-analyses were derived from observational study and most of them came from subgroup with a limited sample size, risk of bias, inconsistency or imprecision. The detailed information about GRADE was shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Main findings and possible explanations

We totally identified 41 meta-analyses with 45 unique outcomes in this umbrella review. According to the existing evidence, milk consumption was more often associated with benefits than harm to a sequence of health-related outcomes. Beneficial associations were found for CVD, stroke, hypertension, CRC, metabolic syndrome, obesity, osteoporosis, T2DM and AD. However, high intake of milk might slightly increase the risk of prostate cancer, PD, acne and Fe-deficiency anaemia in infancy. Side effects including allergy and lactose intolerance need for caution. Dairy products (such as cheese, butter and others) and milk form other species (human, formula milk and donkey, ovine and caprine) consumption was not included in this review because of the complex and different nutritional ingredients.

Milk intake was connected with a lower incidence of CVD in this umbrella review. In the early 1985, the CARDIA study of 4304 participants has indicated that intakes of milk was inversely associated with the elevated blood pressure (BP) over a 15-year follow-up period [71]. RCTs have shown that milk proteins can significantly reduce the systolic BP, diastolic BP, 24-h ambulatory BP, and other risk markers for CVD including total cholesterol (TC) and triacylglycerol [72, 73]. It has been considered that milk fats were important sources for saturated fatty acids (SFAs), which have been related to an elevated risk of CVD because of the high levels of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), therefore, low-fat or fat-free milk rather than regular-fat milk was recommended by some authorities and guidelines [16, 17, 74]. However, outcomes from short-term interventional studies about CVD bio-markers have demonstrated that whole-fat milk would increase LDL-C, while high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was increased as well, and therefore might not influence or even lower the ratio of TC: HDL-C [75]. And a randomized crossover study has found that the differences of whole milk and skimmed milk for TC, LDL-C and triacylglycerol were not significant [76]. In addition, an international collaboration proposed that 2018 World Health Organization draft guideline on dietary SFAs of reducing consumption total of SFAs would be overthrown because which failed to take into account considerable evidence [77]. The mechanisms may be depend on the various components of milk. (1) SFAs (such as C15 and C17) may have a protective effect on CVD in observational studies [78, 79]; (2) CLA and sphingolipids had potential cardio-protective effects [80]; (3) Milk proteins can be digested and generated the bioactive peptides, which were connected with a decreasing hypertension risk [81]; (4) Higher Calcium intake was associated with decreased concentrations of total-C and LDL-C [82], which may have a positive impact on blood lipids, because Ca intake was related to the excretion of fat in the faeces [82]; (5) Milk-derived tripeptides had BP-lowering effects [83]; (6) Notably, the emerging functional ingredient MPL, which are nature component of the milk fat globule membrane [10], can significantly reduce the lipid biomarkers of CVD, including TC/HDL-C and apolipoprotein (Apo)B/ApoA1 ratios by reducing intestinal cholesterol absorption [84]. All of the evidence showed that milk consumption would not rise up the risk of CVD, whereas it may show a protective effect in CVD, which can be included as part of healthy diet [85].

The meaningful finding of this umbrella review was that milk consumption decreased the risk of CRC. Previously in 1977, it has been proposed that higher intake of milk had a protective effect on colon cancer [86]. A recent cohort study included 77,712 Seventh-day Adventists over a mean follow-up 7.8 years has found that milk intake might decrease the risk of CRC [87]. The study of 477,122 participants over a mean follow-up 11 years also found that both whole-fat milk and skimmed milk intake were inversely connected with risk of CRC [84]. The Norwegian Women and Cancer Cohort Study of 81,675 participants indicated that milk consumption was weakly associated with a lower risk of colon cancer among women [88]. Furthermore, milk intake was connected with the mortality of patients with CRC. Yang et al. performed a prospective cohort study with 2284 participants who were diagnosed with invasive non-metastatic CRC proved that post-diagnosis milk consumption was inversely connected with a lower all-cause mortality [89]. Several possible biological mechanisms might underlie the associations: (1) Calcium, the main component of milk can unconcerned about bile acids and FFAs (predominately deoxycholic and lithocolic acids) and prevent or reduce their toxicity to the colonic epithelial cells [90]; (2) Vitamin D would protect against colon cancer, it has been found that higher serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D was related to a decreasing risk of colon cancer [91]; (3) The subtypes of dairy fat could inhibit colorectal carcinogenesis, such as: CLA can inhibit CRC cells growth in vitro [92], and the butyric acid can hamper proliferation and bring about differentiation of tumor cell lines in vitro [90]; (4) The bovine lactoferrin can inhibit CRC and significantly retarded adenomatous colorectal polyp growth [93]; (5) Low-fat milk consumption can reduce the risk of CRC by 60%, especially among individuals with high IGF-1/IGF-binding protein-3 [94]. The WCRF/AICR reported the conclusion of milk consumption probably protected against colorectal cancer [95].

High milk intake was related to an elevated risk of prostate cancer and prostate cancer mortality in our umbrella review. In the early 1984, the associations between prostate cancer and milk consumption have been found [96]. In the later, a prospective cohort study with 25,708 participants followed by 12.4 years found that skim milk consumption was associated with a significantly increased risk of prostate cancer compared with whole milk consumption [97]. The reason was that skim milk was significantly positively associated with BMI [97], and body mass would have an influence on serum androgen concentrations [96]. Recently, the similar results have been found in a multiethnic cohort study with 82,483 men [98]. They suggested that the associations of prostate cancer with milk consumption might vary because of fat content, particularly for the early formation of the cancer [98]. Most interesting, Torfadottir et al. found that high milk consumption in early life (aged 14–19 years) was related to a 3.2-flod risk of advanced prostate cancer after adjusting lifestyle and other factors [99]. In addition, milk consumption was associated with the recurrence and progression of prostate cancer as well. A prospective article with 1334 men confirmed that whole milk consumption more than four servings per week would increase the risk of recurrence by 85% for patients with non-metastatic cancer compared with less three servings a month [100]. Milk consumption after diagnosis was related to a worse progression, Downer et al. conducted a 20-year follow-up study with 525 men who were recently diagnosed with prostate cancer and found that high-fat milk consumption more than 3 servings daily was associated with higher risk of mortality from prostate cancer among agents with localized prostate cancer compared with the low volume consumers [101]. The following mechanisms have been proposed: (1) Milk consumption was associated with higher circulating IGF-1 levels may be in line with the risk of prostate cancer [102]. Each 200 g increment in milk per day was related to 10.0 ug/L higher IGF-1 [102]; (2) The casein would contribute to the proliferation of prostate cancer cells including PC3 and LNCaP [103]; (3) Milk would disrupt the p53 and DNA methyltransferase 1 and promote prostate cancer, which were the guardians of the genome [104]; (4) Calcium and phosphorous may decrease concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D, which can inhibit the carcinogenesis of prostate and contribute to apoptosis [101]. An overview [105] and the WCRF/AICR report [106] concluded that milk consumption probably increased prostate cancer risk, while the evidence was limited.

Beneficial associations were found between milk consumption and metabolic syndrome, T2DM, and obesity. The cohort studies with 7240 adults in Korean found that the people consumed more than seven servings per week had a half reduction of metabolic syndrome risk, and the individual components such as elevated blood pressure, hypertriacylglycerolaemia, abdominal obesity and hyperglycaemia were reduced as well compared with non-drinkers [107]. Another prospective cohort study with 63,257 Chinese people found that high milk consumption was significantly connected with a 12% decrease in the risk of T2DM [108]. And the effects were increased with the volume of milk consumption, A prospective cohort study (Shanghai Women’s Health Study), based on population with 64,191 women aged 40–70 years from 7 urban communities in Shanghai, found that the associations followed a dose-dependent relationship, the HR of T2DM was 0.61 for < 100 g/day, 0.56 for 100–200 g/day, and 0.46 for > 200 g/day milk consumption compared with non-consumers [109]. Besides, milk consumption was also inversely associated with obesity, each increment 100 ml/d was associated with 0.26 kg/m2 lower BMI [83]. A meta-analysis of 37 RCTs manifested that high dairy intake was associated with lower body weight and body fat while higher lean mass with energy restriction [110]. The main components of milk such as calcium and magnesium [109], Casein and whey protein [5], trans-11 vaccenic acid [111], linoleic acid [112], MPL [10], vitamin D [113], and its effect on enhancing satiety [114] may be responsible for the mechanism behind the beneficial associations.

The associations between milk consumption and neurological outcomes were mixed in this article. Milk consumption was beneficial to AD while being harmful for PD. Prospective cohort study (the Hisayama Study) with 1018 elderly Japanese over 17 years of follow-up has found that greater milk intake reduced the risk of dementia, especially AD with a linear relationship [115]. The possible mechanisms were proposed that milk and its components such as milk peptide [116], β-Casein [117], calcium and magnesium [115], would tribute to the low risk of AD by suppressing the expression of inflammatory cytokines and production of oxidative stress [118], inhibiting the aggregation and deposition of Aβ1-42 fibrils [117] and other mechanisms. However, several prospective cohort studies (such as the Nurses' Health Study, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study) have found that high milk consumption was associated with elevated risk of PD [119], and the risk of PD was 2.3-fold in the highest group (sixteen Ounces per day) compared with lowest group in the Hnolulu Heart Program [120]. But there were no clear explanations for the associations. Possible explanations included pesticides residues in milk such as organochlorine and tetrahydroisoquinoline [121], and milk protein casein may increase the risk of PD by reducing serum urate or uric acid concentrations [122]. Based on currently evidence, limiting the consumption of milk was not a reasonable strategy in the prevention of PD [123].

Milk intake might increase the risk and severity of acne in this review [59]. A Norwegian longitudinal study in 2489 adolescence found that high consumption of milk would increase the risk of acne in girls but not in boys [124]. The gender differences would be due to the different pattern of dairy intake, maturational stage and life styles [124]. Another recent meta-analysis of observational studies in individuals aged 7–30 years also demonstrated milk consumption was related to a higher risk of acne, not only for whole milk but also low-fat or skimmed milk, and the effects were significantly related to the frequency of milk consumption [125]. The possible explanation was that milk would increase the insulin and IGF-1 concentration [102] which would promote the phosphorylation of transcription factor Forkhead box protein O1, trigger the nutrient sensitive kinase, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, stimulate the sebaceous glands and result in occurrence of acne [126, 127]. However, the Mendelian randomization study with 20,416 Danish adults failed to observe the associations between milk consumption and acne [128]. Therefore, more RCTs are needed in the further research to clarify the causal association especially in adolescence.

Cow’s milk consumption was related to over three-fold risk of Fe-deficiency anaemia in infancy compared with those who consumed follow-on formula in our review. Summary analysis from of cohorts has revealed that the incidence of iron deficiency was highest in cow’s milk group compared with breast milk or follow-on formula [129]. A double-blind RCT showed that the prevalence of Fe-deficiency anaemia was 33% in cow’s milk group while 2% in iron supplemented group [130]. Several mechanisms have been identified: (1) The most important was the low iron content (0.5 mg/L) of cow’s milk [131]; (2) Milk consumption during infancy would result in occult intestinal blood loss [132]; (3) The components of milk including calcium and casein would inhibit the absorption of non-heme iron [131, 133]. Fe-fortified milk or follow-on formula would be efficacious ways to prevent the occurrence of Fe-deficiency anaemia [130].

Milk allergy has been described in modern literature by Hamburger in 1901 [134]. In the later, antigens in cow's milk were identified [135]. Recently, several approaches were found to prevent and treat milk allergy [136, 137]. The notion of lactose intolerance can date back to the mid-twentieth century when the severe lactose intolerance in infancy was found [138]. In the second half of twentieth century, it was found that the lactose intolerance was genetically-determined [139]. Nowadays, many options were used to prevent the abdominal and gastrointestinal symptoms of lactose intolerance [140, 141].

In addition, some health professionals not advising the consumption of milk because it could cause an inflammatory process. However, there was no evidence showed the association. Recently, several publications have shown that milk and dairy production consumption were not related to the inflammatory response [142–144]. A systematic review of 15 latest RCTs evaluated the scientific evidence of the effects of milk on inflammatory bio-markers, and found that consumption of milk did not show a pro-inflammatory effect in healthy subjects or individuals with metabolic abnormalities (who were obese, overweight or who had T2DM or metabolic syndrome) and even had a significant anti-inflammatory effect in both healthy and metabolically abnormal subjects [142].

Strengths and limitations

The umbrella review systematically summarized the current evidence for milk intake and a range of health-related outcomes for humanity. The AMSTAR 2 and GRADE were used to assess the quality of methods and the evidence for each included meta-analyses. However, several possible limitations should be considered. The article with pooled analysis were included. Those without meta-analyses were omitted, which would have impacts on the outcomes. Besides, we are unable to analyze the associations of different types of milk (whole/high-fat/low-fat/skimmed) with individual outcomes, because most of the articles did not distinguish the different types of milk. In addition, most of the outcomes came from observational study, which may limit the association effects for each outcome due to heterogeneity and bias across studies [145]. Since this umbrella review aim to investigate the association of milk consumption and health outcomes, the physiological outcomes were omitted. In addition, some studies showed that there was a dose dependent effect, while we were unable to conduct the dose–response analysis, more work should be done to elucidate the dosage and effects of milk consumption on human health.

Conclusions

Milk consumption has been investigated for association with a diverse range of health outcome in a large amount of meta-analyses. In this umbrella review, milk consumption does more good than harm for human health. Our results support milk consumption as part of a healthy diet. More well-designed RCTs are warranted in the future.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1: Full versions of total summary data for the meta-analyses of association between milk consumption and health outcomes.

Additional file 2. Table S2: The detailed results of AMSTAR 2 of each meta-analysis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MPL

Milk polar lipids

- ALA

α-Linolenic acid

- CLA

Conjugated linoleic acids

- OR

Odds ratio

- RR

Relative risk

- HR

Hazard ratio

- MD

Mean difference

- SMD

Standardized mean differences

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- CI

Confidence interval

- AMSTAR

A measurement tool to assess systematic reviews

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- BP

Blood pressure

- TC

Total cholesterol

- SFAs

Saturated fatty acids

- LDL-C

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Apo

Apolipoprotein

- MA

Meta-analysis

- FFAs

Free fatty acids

- NHL

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DLBCL

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- FL

Follicular lymphoma

- SLL/CLL

Small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- NA

Not available

- PC

Prostate cancer

- FDA

Fe-deficiency anaemia

- HTG

Hypertriacylglycerolaemia

- T1DM

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

Authors’ contributions

Prof. YZ, KL and XZ conceived together the study. XZ, XC, YX, JY and LD preformed data extraction, analysis and interpretation. XZ wrote the manuscript under the guidance of Prof. YZ and KL. All authors have read the manuscript and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Chinese Medical Board Grant on Evidence-Based Medicine, New York, USA (No. 98-680), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30901427) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71974135). Mainly used for literature search and language.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ka Li, Email: lika127@126.com.

Yong Zhou, Email: nutritioner@hotmail.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12986-020-00527-y.

References

- 1.Evershed RP, Payne S, Sherratt AG, Copley MS, Coolidge J, Urem-Kotsu D, et al. Earliest date for milk use in the near east and southeastern Europe linked to cattle herding. Nature. 2008;455:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature07180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudd SN, Evershed RP. Direct demonstration of milk as an element of archaeological economies. Science. 1998;282:1478–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global and regional food consumption patterns and trends. 2018. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/3_foodconsumption/en/index4.html.

- 4.Michaëlsson K, Wolk A, Langenskiöld S, Basu S, Warensjö E, Melhus H, et al. Milk intake and risk of mortality and fractures in women and men: cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;349:g6015. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouglé D, Bouhallab S. Dietary bioactive peptides: human studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:335–343. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.873766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulgoni VL, Keast DR, Bailey RL, Dwyer J. Foods, fortificants, and supplements: where do Americans get their nutrients? J Nutr. 2011;141(10):1847–1854. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.142257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parodi PW. Cows' milk fat components as potential anticarcinogenic agents. J Nutr. 1997;127:1055–1060. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva MS, Rudkowska I. Dairy nutrients and their effect on inflammatory profile in molecular studies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59:1249–1263. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sultan S, Huma N, Butt MS, Aleem M, Abbas M. Therapeutic potential of dairy bioactive peptides: a contemporary perspective. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:105–115. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1136590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milard M, Laugerette F, Durand A, Buisson C, Meugnier E, Loizon E, et al. Milk polar lipids in a high-fat diet can prevent body weight gain: modulated abundance of gut bacteria in relation with fecal loss of specific fatty acids. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1801078. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He J, Wofford MR, Reynolds K, Chen J, Chen CS, Myers L, et al. Effect of dietary protein supplementation on blood pressure: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2011;124:589–595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor S, Greffard K, Leclercq M, Julien P, Weisnagel SJ, Gagnon C, et al. Increased dairy product intake alters serum metabolite profiles in subjects at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1900126. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cadogan J, Eastell R, Jones N, Barker ME. Milk intake and bone mineral acquisition in adolescent girls: randomised, controlled intervention trial. BMJ. 1997;315:1255–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7118.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organisation European Region . Food based dietary guidelines in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO, Europe; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Food and Agricultural Organization, World Heath Organisation . Preparation and use of food-based dietary guidelines. Report of a joint FAO/WHO consultation. Nicosia, Cyprus: WHO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Horn L, Carson JA, Appel LJ, Burke LE, Economos C, Karmally W, et al. Recommended dietary pattern to achieve adherence to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e505–e529. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Department of Agriculture (US). 2015–2020 dietary guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

- 18.Givens DI. Milk in the diet: good or bad for vascular disease? Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:98–104. doi: 10.1017/S0029665111003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tieri M, Ghelfi F, Vitale M, Vetrani C, Marventano S, Lafranconi A, et al. Whole grain consumption and human health: an umbrella review of observational studies. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2020;71:668–677. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2020.1715354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavero RI, Alvarez BC, Sotos-Prieto M, Gil A, Martinez-Vizcaino V, Ruiz JR. Milk and dairy product consumption and risk of mortality: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S97–S104. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papatheodorou S. Umbrella reviews: what they are and why we need them. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:543–546. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ioannidis JP. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ. 2009;181:488–493. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:132–140. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi M, Wu X, Zhuang W, Xia L, Chen Y, Zhao R, et al. Tea Consumption and health outcomes: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1900389. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li N, Wu X, Zhuang W, Xia L, Chen Y, Zhao R, et al. Soy and isoflavone consumption and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomized trials in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2020;64:e1900751. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence-inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dehghan M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, Sheridan P, Mohan V, Iqbal R, et al. Association of dairy intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 21 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392:2288–2297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazidi M, Mikhailidis DP, Sattar NG, Graham I, Banach M, Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group Consumption of dairy product and its association with total and cause specific mortality—a population-based cohort study and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:2833–2845. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Sullivan TA, Hafekost K, Mitrou F, Lawrence D. Food sources of saturated fat and the association with mortality: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e31–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu W, Chen H, Niu Y, Wu H, Xia D, Wu Y. Dairy products intake and cancer mortality risk: a meta-analysis of 11 population-based cohort studies. Nutr J. 2016;15:91. doi: 10.1186/s12937-016-0210-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo J, Astrup A, Lovegrove JA, Gijsbers L, Givens DI, Soedamah-Muthu SS. Milk and dairy consumption and risk of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:269–287. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullie P, Pizot C, Autier P. Daily milk consumption and all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1236. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3889-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Goede J, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Pan A, Gijsbers L, Geleijnse JM. Dairy consumption and risk of stroke: a systematic review and updated dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Ding EL, Al-Delaimy WK, Hu FB, Engberink MF, Willett WC, et al. Milk and dairy consumption and incidence of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:158–171. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Verberne LDM, Ding EL, Engberink MF, Geleijnse JM. Dairy consumption and incidence of hypertension: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Hypertension. 2012;60:1131–1137. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.195206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrubés L, Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Rosique-Esteban N, Salas-Salvadó J. Association between dairy product consumption and colorectal cancer risk in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S190–S211. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aune D, Navarro Rosenblatt DA, Chan DSM, Vieira AR, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, et al. Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:87–117. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.067157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Li X, Zhang D. Dairy product consumption and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2016;8:120. doi: 10.3390/nu8030120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Zhou M, Ji A, He J. Milk/dairy products consumption and gastric cancer: an update meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Oncotarget. 2018;9:7126–7135. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bermejo LM, López-Plaza B, Santurino C, Cavero-Redondo I, Gómez-Candela C. Milk and dairy product consumption and bladder cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S224–S238. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J, Zeng R, Huang J, Li X, Zhang J, Ho JC, et al. Dietary protein sources and incidence of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Nutrients. 2016 doi: 10.3390/nu8110730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J, Tang W, Sang L, Dai X, Wei D, Luo Y, et al. Milk, yogurt, and lactose intake and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:68–72. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.956247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li K, Sinclair AJ, Zhao F, Li D. Uncommon fatty acids and cardiometabolic health. Nutrients. 2018 doi: 10.3390/nu10101559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li B, Jiang G, Xue Q, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhang GX, et al. Dairy consumption and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12:e269–e279. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y, Zhou J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: dairy consumption and hepatocellular carcinoma risk. J Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10389-017-0806-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Wang X, Yao Q, Qin L, Xu C. Dairy product, calcium intake and lung cancer risk: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20624. doi: 10.1007/s10389-017-0806-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genkinger JM, Wang M, Li R, Albanes D, Anderson KE, Bernstein L, et al. Dairy products and pancreatic cancer risk: a pooled analysis of 14 cohort studies. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1106–1115. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian S, Xu Q, Jiang R, Han T, Sun C, Na L. Dietary protein consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutrients. 2017 doi: 10.3390/nu9090982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mena-Sánchez G, Becerra-Tomás N, Babio N, Salas-Salvadó J. Dairy product consumption in the prevention of metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S144–S153. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang W, Wu Y, Zhang D. Association of dairy products consumption with risk of obesity in children and adults: a meta-analysis of mainly cross-sectional studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(870–882):e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee M, Lee H, Kim J. Dairy food consumption is associated with a lower risk of the metabolic syndrome and its components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:373–384. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matía-Martín P, Torrego-Ellacuría M, Larrad-Sainz A, Fernández-Pérez C, Cuesta-Triana F, Rubio-Herrera MÁ. Effects of milk and dairy products on the prevention of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures in Europeans and Non-Hispanic Whites from North America: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S120–S143. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malmir H, Larijani B, Esmaillzadeh A. Consumption of milk and dairy products and risk of osteoporosis and hip fracture: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60:1722–1737. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1590800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee J, Fu Zh, Chung M, Jang DJ, Lee HJ. Role of milk and dairy intake in cognitive function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J. 2018;17:82. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang W, Ju C, Jiang H, Zhang D. Dairy foods intake and risk of Parkinson's disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:613–619. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9921-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griebler U, Bruckmüller MU, Kien C, Dieminger B, Meidlinger B, Seper K, et al. Health effects of cow's milk consumption in infants up to 3 years of age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:293–307. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aghasi M, Golzarand M, Shab-Bidar S, Aminianfar A, Omidian M, Taheri F. Dairy intake and acne development: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1067–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoorsan H, Mirmiran P, Chaichian S, Yousef M, Fatemeh J. Diet and risk of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2017 doi: 10.5812/ircmj.41248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Zou Y, Ding G. Dietary factors associated with dental erosion: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, Gislason D, Zuidmeer L, Sodergren E, et al. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chafen Jennifer JS, Newberry SJ, Riedl Marc A, Bravata DM, Maglione M, et al. Diagnosing and managing common food allergies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;303:1848–1856. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yeung JP, Kloda LA, McDevitt J, Ben-Shoshan M, Alizadehfar R. Oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD009542. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009542.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martorell CC, Muriel GA, Martorell AA, De La Hoz CB. Safety and efficacy profile and immunological changes associated with oral immunotherapy for IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24:298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suchy FJ, Brannon PM, Carpenter TO, Fernandez JR, Gilsanz V, Gould JB. NIH consensus development conference statement: lactose intolerance and health. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2010;27:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Savaiano Dennis A, Boushey Carol J, McCabe George P. Lactose intolerance symptoms assessed by meta-analysis: a grain of truth that leads to exaggeration. J Nutr. 2006;136:1107–1113. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.4.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harvey L, Ludwig T, Hou Alice Q, Hock QS, Tan ML, Osatakul S. Prevalence, cause and diagnosis of lactose intolerance in children aged 1–5 years: a systematic review of 1995–2015 literature. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2018;27:29–46. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.022017.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaukat A, Levitt MD, Taylor BC, MacDonald R, Shamliyan TA, Kane RL. Systematic review: effective management strategies for lactose intolerance. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:797–803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gijsbers L, Ding EL, Malik VS, de Goede J, Geleijnse JM, Soedamah-Muthu SS. Consumption of dairy foods and diabetes incidence: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1111–1124. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.123216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steffen LM, Kroenke CH, Yu X, Pereira MA, Slattery ML, Van Horn L. Associations of plant food, dairy product, and meat intakes with 15-y incidence of elevated blood pressure in young black and white adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1169–1177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fekete ÁA, Givens DI, Lovegrove JA. Casein-derived lactotripeptides reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure in a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Nutrients. 2015;7:659–681. doi: 10.3390/nu7010659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fekete ÁA, Giromini C, Chatzidiakou Y, Givens DI, Lovegrove JA. Whey protein lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial function and lipid biomarkers in adults with prehypertension and mild hypertension: results from the chronic Whey2Go randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1534–1544. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.137919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alexander DD, Bylsma LC, Vargas AJ, Cohen SS, Doucette A, Mohamed M, et al. Dairy consumption and CVD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2016;115:737–750. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515005000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huth PJ, Park KM. Influence of dairy product and milk fat consumption on cardiovascular disease risk: a review of the evidence. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:266–285. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Engel S, Elhauge M, Tholstrup T. Effect of whole milk compared with skimmed milk on fasting blood lipids in healthy adults: a 3-week randomized crossover study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:249–254. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Astrup A, Bertram HC, Bonjour J, de Groot LC, de Oliveira Otto MC, Feeney EL, et al. WHO draft guidelines on dietary saturated and trans fatty acids: time for a new approach? BMJ. 2019;366:l4137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yan Y, Wang Z, Greenwald J, Kothapalli KS, Park HG, Liu R, et al. BCFA suppresses LPS induced IL-8 mRNA expression in human intestinal epithelial cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2017;116:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liang J, Zhou Q, Kwame Amakye W, Su Y, Zhang Z. Biomarkers of dairy fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:1122–1130. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1242114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fontecha J, Calvo Maria V, Juarez M, Gil A, Martínez-Vizcaino V. Milk and dairy product consumption and cardiovascular diseases: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S164–S189. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marcone S, Belton O, Fitzgerald DJ. Milk-derived bioactive peptides and their health promoting effects: a potential role in atherosclerosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:152–162. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kjølbæk L, Lorenzen JK, Larsen LH, Astrup A. Calcium intake and the associations with faecal fat and energy excretion, and lipid profile in a free-living population. J Nutr Sci. 2017;6:e50. doi: 10.1017/jns.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hartwig FP, Horta BL, Smith GD, de Mola CL, Victora CG. Association of lactase persistence genotype with milk consumption, obesity and blood pressure: a Mendelian randomization study in the 1982 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort, with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1573–1587. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Murphy N, Norat T, Ferrari P, Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Skeie G, et al. Consumption of dairy products and colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benatar JR, Jones E, White H, Stewart RA. A randomized trial evaluating the effects of change in dairy food consumption on cardio-metabolic risk factors. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:1376–1386. doi: 10.1177/2047487313493567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maclennan R, Jensen OM. Dietary fibre, transit-time, faecal bacteria, steroids, and colon cancer in two Scandinavian populations. Report from the International Agency for Research on Cancer Intestinal Microecology Group. Lancet. 1977;2:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tantamango-Bartley Y, Knutsen SF, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Fan J, Mashchak A, Fraser GE. Independent associations of dairy and calcium intakes with colorectal cancers in the Adventist Health Study-2 cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:2577–2586. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bakken T, Braaten T, Olsen A, Hjartåker A, Lund E, Skeie G. Milk and risk of colorectal, colon and rectal cancer in the Norwegian Women and Cancer (NOWAC) Cohort Study. Br J Nutr. 2018;119:1274–1285. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518000752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang B, McCullough ML, Gapstur SM, Jacobs EJ, Bostick RM, Fedirko V, et al. Calcium, vitamin D, dairy products, and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors: the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2335–2343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Norat T, Riboli E. Dairy products and colorectal cancer. A review of possible mechanisms and epidemiological evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Garland CF, Comstock GW, Garland FC, Helsing KJ, Shaw EK, Gorham ED. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colon cancer: eight-year prospective study. Lancet. 1989;2:1176–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shultz TD, Chew BP, Seaman WR, Luedecke LO. Inhibitory effect of conjugated dienoic derivatives of linoleic acid and beta-carotene on the in vitro growth of human cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 1992;63(2):125–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90062-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kozu T, Iinuma G, Ohashi Y, Saito Y, Akasu T, Saito D, et al. Effect of orally administered bovine lactoferrin on the growth of adenomatous colorectal polyps in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:975–983. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]