Abstract

Currently, serum carcinoembryonic agent (CEA) along with contrast-enhanced imaging and colonoscopy are used for evaluation of recurrence of colorectal cancer. However, CEA is an unreliable and nonspecific biomarker that may fail to rise and signal relapse. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in patients offers a minimally invasive method to assess risk of relapse several months ahead of conventional clinical means. Here, we report the case of a colon adenocarcinoma with postoperative liver metastasis diagnosed early by ctDNA measurement, using a personalized NGS-mPCR assay. While ctDNA levels continued to rise, CEA levels tested negative. Metastatic relapse to the liver was promptly confirmed by PET/CT scan. The patient underwent a successful metastasectomy with curative intent. Following surgery, the patient exhibited no evidence of disease and ctDNA levels remained negative. Our case report suggests that the early detection of postoperative molecular residual disease by means of ctDNA measurement can accurately predict mCRC relapse in cases where CEA levels fail to increase. Close monitoring of ctDNA levels during the postoperative period can allow for earlier intervention and more favorable outcomes in relapsing mCRC patients.

Keywords: Carcinoembryonic agent, Circulating tumor DNA, Liver metastasis, Metastatic colorectal cancer

Introduction

Oligometastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) is considered curable for patients with isolated and surgically resectable lung and/or liver metastases [1]. However, a relapse rate of approximately 60% has been observed following metastasectomy [2], mainly attributed to the presence of clinically occult molecular residual disease (MRD) post-surgery [3]. Advances in next-generation sequencing technology have led to the use of liquid biopsies for measuring circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in patient blood, as readout for postsurgical MRD [3, 4]. In patients with resected CRC, positive postoperative ctDNA strongly correlates with disease recurrence [4, 5]. Longitudinal ctDNA analysis to monitor disease status postoperatively enables early detection of cancer recurrence, creating opportunities for surgical/therapeutic intervention [4]. Using postoperative ctDNA status to guide adjuvant therapy selection is currently being evaluated in multiple prospective clinical trials (NCT04068103, NCT04264702, and NCT030803553).

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old African-American man presented with abdominal pain, an unintentional 15-pound weight loss, and a palpable left lower quadrant mass. CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed an 8.5 cm circumferential partially obstructing mass in the left colon with thickening of the adjacent peritoneum (Fig. 1, 2a). Carcinoembryonic agent (CEA) measured at this time was 1.2 ng/mL (within the normal range). Due to oral intolerance, the patient was admitted for urgent colonoscopy which revealed a sigmoid colon mass 25 cm from the anal verge. Biopsy findings confirmed it to be an adenocarcinoma. The next day, the patient underwent low anterior resection with final pathology revealing a 7.3 cm moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon, pT3pN0M0 stage IIA, 0/36 LNs positive, negative margins, no evidence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion, and a microsatellite instability high phenotype.

Fig. 1.

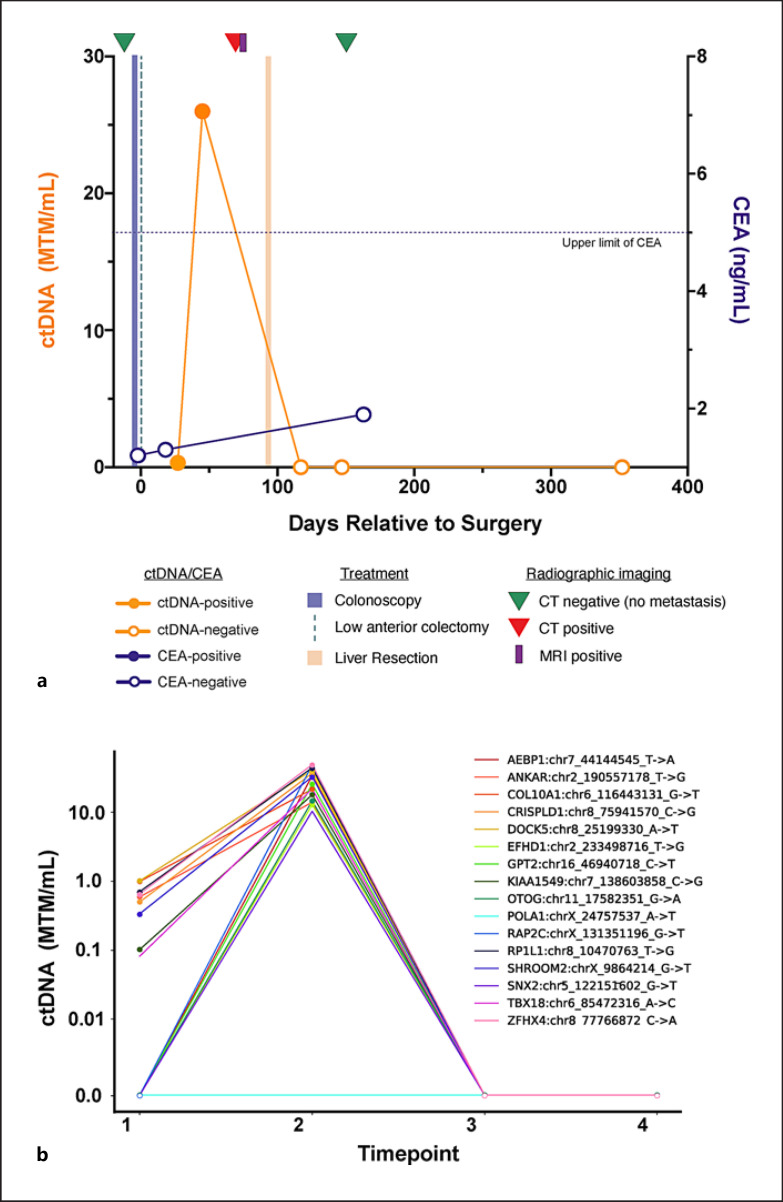

Patient ctDNA dynamics throughout clinical course: a composite ctDNA changes as measured in mean tumor MTM of plasma (MTM/mL) represented along with radiographic imaging and treatment. b Individual 16 variants identified using Signatera (mPCR-NGS-based ctDNA assay). ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; MTM, molecules per milliliter.

Fig. 2.

Patient CT scan results. a CT scan 10 days before surgery (−10) revealed an 8.5 cm circumferential partially obstructing mass in the left colon with thickening of the adjacent peritoneum. b Post-op day 72 CT scan (+72) identified new FDG-avid, 2.2 × 2.0 cm mass in segment 4A of the liver, consistent with metastatic disease.

The patient was readmitted to the hospital postoperatively with a small bowel obstruction attributed to postoperative adhesions. Imaging at this time revealed a transition point in the left lower quadrant, with thickening and enhancement of adjacent peritoneum. The patient was managed nonoperatively with nasogastric decompression and was discharged.

The patient was planned for surveillance of his stage IIA colon cancer with serial CEA measurement and CT scanning. CEA on post-op day 18 was again normal (1.3 ng/mL). Given the findings of peritoneal thickening and enhancement at the time of the patient's postoperative bowel obstruction, serial ctDNA monitoring using a personalized NGS-mPCR ctDNA assay (SignateraTM, Natera, Austin, and TX) and early interval CT scanning were planned. The patient's initial ctDNA measurement on post-op day 27 was positive, measuring 0.32 mean tumor molecules per milliliter (MTM/mL) (a). Subsequent ctDNA testing on post-op day 45 revealed an increase in ctDNA to 25.99 MTM/mL. Given the rising ctDNA and a concern for residual or recurrent disease in the left lower quadrant, PET/CT was performed on post-op day 72 (Fig. 2b), delayed due to insurance approval. This revealed a new FDG-avid, 2.2 × 2.0 cm mass in segment 4A of the liver, consistent with metastatic disease. An abdominal MRI with and without contrast on post-op day 74 confirmed this finding and also demonstrated a sub-centimeter segment 7 hepatic lesion that had been stable from baseline pre-op imaging and was not FDG-avid.

Based on these findings, the patient was taken for exploratory laparotomy, intraoperative ultrasound, segment 4A segmentectomy, segment 7 wedge resection, cholecystectomy, and portal lymphadenectomy on post-op day 95. Pathology demonstrated metastatic moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, consistent with sigmoid colon metastasis, measuring 2.7 cm in segment 4A. The segment 7 lesion was a benign sclerosed hemangioma, all margins were negative, and 0/3 lymph nodes were positive. Following surgical resection of this isolated hepatic metastasis, the patient's ctDNA cleared to a value of 0.00 MTM/mL on post-op day 117. ctDNA levels remained negative on post-op day 147.

The patient's primary sigmoid tumor was sent for comprehensive genomic profiling using the Caris Life Sciences (Phoenix, AZ) platform. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the following molecular phenotype: mismatch repair deficiency (loss of MLH1 and PMS2), PD-L1 negative (0% using SP142 stain), PTEN positive (2+, 100%), and Her2/Neu negative (0). DNA sequencing revealed microsatellite instability high, high tumor mutational burden (17 mutations per megabase) a pathogenic mutation in PIK3CA (H1047L), wild-type BRAF, KRAS, and NRAS, a likely pathogenic mutation in BCL9, and other pathogenic mutations in ASXL1, ATM, CDH1, CDKN1B, CTNNB1, EZH2, FLCN, KDM6A, MSH3, and NBN. Ambry germ line testing revealed a variant of unknown significance in MLH1 (E679G), and MLH1 promoter methylation (ARUP Laboratories) was not detected.

Regarding the patient's long-term outcome and relapse-free survival, CT at day 158 and ctDNA analysis up to day 352 was negative. Therefore, the relapse-free survival was 2 months on imaging and 8.5 months with ctDNA analysis.

Discussion

The above case illustrates the ability of personalized ctDNA monitoring to identify early relapse or persistent disease following curative-intent resection. In this case, a positive and rising ctDNA result supported an early escalation to PET/CT, which in turn allowed for curative intent metastasectomy. Had the patient not had ctDNA testing, it is possible his metastatic disease would have progressed prior to discovery, depriving the patient a second chance for surgical cure. In addition, typical surveillance with blood-based CEA measurements is often ineffective in patients with normal baseline pre-op CEA levels, as was the case in this patient.

Emerging evidence suggests that negative ctDNA levels post-curative intent metastasectomy, using a tumor-informed approach is a strong positive predictor for overall survival (OS). A recent study reported MRD positivity rates as high as 49% (26/53) post-metastasectomy, which is consistent with other published studies in the oligometastatic setting. Additionally, the study showed improved ctDNA detection rates with increased time from surgery [6, 7]. In another study of 112 patients undergoing metastasectomy with curative intent, median disease-free survival was significantly shorter in patients with postoperative ctDNA-positive status (HR 5.8, 95% CI: 3.5–9.7; p < 0.001) as was OS (HR 16.0, 95% CI: 3.9–68.0, p < 0.001) [8]. In addition, patients who did not receive systemic therapy and were ctDNA-negative at the last follow-up time point showed 100% OS.

The ctDNA assay utilized in this case report reflects the power of tumor-informed, blood-based, personalized testing that relies on the prior knowledge of the mutational status of the patient's tumor and is designed to detect 16 clonal single nucleotide variants. Tracking clonal variants provides an advantage as these are not susceptible to treatment-induced attrition and can be confidently tracked to measure disease progression/treatment response. Signatera has been shown to detect MRD with high sensitivity (down to 0.01% VAF) and specificity (99.8%) [9]. In a recent publication by Henriksen et al. [10], the detection of molecular relapse in patients with stage III CRC has shown to precede radiological findings by a median of 9.8 months, offering an early intervention window for potential cure. Other commercially available ctDNA tests are tumor-naïve or are designed to only measure static panels of mutations that frequently occur in a given tumor type, the sensitivity of which can be impacted by tumor heterogeneity. A recent study by Loupakis et al. [8] investigated and compared the performance of ddPCR and Signatera tumor-informed ctDNA test for prediction of relapse and found that the tumor-informed approach had a greater sensitivity. Furthermore, our case demonstrates that ctDNA has the potential to detect early recurrence and development of metastatic disease, particularly in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer who would otherwise be considered suitable for surveillance alone. The use of CEA as a biomarker for disease monitoring is limited, as many CRC tumors do not produce significant quantities of CEA. In addition to guiding decision-making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy, early ctDNA positivity should prompt reimaging at earlier than typical time points, as demonstrated in our case report.

A limitation of our study is that it is a single patient longitudinal study that is not sufficient to establish ctDNA testing as a disease monitoring tool. Additionally, this study does not provide guidance on the ctDNA testing interval during surveillance. A ctDNA surveillance plan should be designed at the discretion of the treating physician and should take into account the type, stage, and grade of the tumor, biomarker status, treatment type, treatment resistance, and other diagnostic results. In a multicenter, prospective, observational clinical study designed to monitor the impact of ctDNA testing (Signatera) in stage I-IV CRC patients, ctDNA testing is recommended to take place at least at 2 weeks or between 2 and 6 weeks after surgery, in order to inform on postsurgical treatment decision, followed by every 4 weeks through 20 weeks and every 3 months thereafter [11]. Since surgery-induced trauma may cause elevation in the total cell-free DNA levels and could confound the detection of ctDNA, a recent study suggested a repeat ctDNA testing 4 weeks post-surgery in ctDNA-negative patients. This approach can help avoid false-negative results [12]. We believe the data from this prospective clinical study and others will validate ctDNA as a predictive biomarker of benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted ethically, in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. This report was granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) per the regulatory definition 45CFR46.102. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

B.A.W., E.R.W., and M.B. declare no competing interests. M.K., P.M.O., P.R.B., and A.A. are employees of Natera, Inc. with stock/options to own stock in the company.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by Natera, Inc. This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

B.A.W., M.K., and P.O., A.A contributed to conceptualization. B.A.W., M.K., E.R.W., and M.B contributed to data acquisition/curation. B.A.W. and M.K contributed to data analysis/interpretation. B.A.W. and M.R.K contributed to writing − original draft. B.A.W., E.R.W., M.B., M.R.K., P.M.O, P.R.B., and A.A contributed to writing − reviewing and editing.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Weiser MR, Jarnagin WR, Saltz LB. Colorectal cancer patients with oligometastatic liver disease: what is the optimal approach? Oncology. 2013 Nov;27((11)):1074–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunawardene A, Desmond B, Shekouh A, Larsen P, Dennett E. Disease recurrence following surgery for colorectal cancer: five-year follow-up. N Z Med J. 2018 Feb 2;131((1469)):51–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naidoo M, Gibbs P, Tie J. ctDNA and adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer: time to re-invent our treatment paradigm. Cancers. 2021 Jan 19;13((2)):346. doi: 10.3390/cancers13020346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinert T, Henriksen TV, Christensen E, Sharma S, Salari R, Sethi H, et al. Analysis of plasma cell-free DNA by ultradeep sequencing in patients with stages I to III colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019 May 9;5((8)):1124–31. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tie J, Cohen JD, Wang Y, Christie M, Simons K, Lee M, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analyses as markers of recurrence risk and benefit of adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Oct 17;5:1710–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schøler LV, Reinert T, Ørntoft MW, Kassentoft CG, Árnadóttir SS, Vang S, et al. Clinical implications of monitoring circulating tumor DNA in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Sep 15;23((18)):5437–45. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S, Hook N, Krinshpun S, Westbrook L, Loranger K, Wallace J, et al. SO-34 clinical experience of a personalized and tumor-informed circulating tumor DNA assay for minimal residual disease detection in oligometastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loupakis F, Sharma S, Derouazi M, Murgioni S, Biason P, Rizzato MD, et al. Detection of molecular residual disease using personalized circulating tumor DNA assay in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing resection of metastases. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:1166–77. doi: 10.1200/PO.21.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coombes RC, Page K, Salari R, Hastings RK, Armstrong A, Ahmed S, et al. Personalized detection of circulating tumor DNA antedates breast cancer metastatic recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2019 Jul 15;25((14)):4255–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriksen TV, Tarazona N, Frydendahl A, Reinert T, Gimeno-Valiente F, Carbonell-Asins JA, et al. Circulating tumor DNA in stage III colorectal cancer, beyond minimal residual disease detection, towards assessment of adjuvant therapy efficacy and clinical behavior of recurrences. Clin Cancer Res. 2021 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasi PM, Sawyer S, Guilford J, Munro M, Ellers S, Wulff J, et al. BESPOKE study protocol: a multicentre, prospective observational study to evaluate the impact of circulating tumour DNA guided therapy on patients with colorectal cancer. BMJ open. 2021;11((9)):e047831. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriksen TV, Reinert T, Christensen E, Sethi H, Birkenkamp-Demtröder K, Gögenur M, et al. The effect of surgical trauma on circulating free DNA levels in cancer patients: implications for studies of circulating tumor DNA. Mol Oncol. 2020 May 29;14:1670–9. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.