Abstract

Background

Chronic inflammation has been described in people living with HIV (PLHIV) receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) despite viral suppression. Inflammation associated non-communicable diseases, including atherosclerosis, are becoming recognized complication of HIV infection. We studied the effect of pitavastatin on atherosclerotic-associated inflammatory biomarkers in PLHIV receiving ART.

Methods

A randomized, double-blind, crossover study was conducted in HIV-infected persons with dyslipidemia and receiving atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/r) to evaluate the effect of 2 mg/day pitavastatin treatment versus placebo. High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), cytokines, and cellular markers in PLHIV receiving 12 weeks of pitavastatin or placebo were investigated.

Results

A total of 24 HIV-infected individuals with a median (interquartile range) age of 46 (41–54) years were recruited, and the median CD4 T cell count was 662 (559-827) cells/mm3. The median duration of ATV/r use was 36 (24–48) months. Significant change in levels of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) between pitavastatin treatment and placebo at week 12 from baseline was observed (27.1 vs. 20.5 pg/mL; p=0.023). However, there were no significant changes from baseline of hs-CRP and other plasma cytokine levels at week 12 of pitavastatin or placebo. Regarding cellular markers, percentages of HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells and PD1+CD4+ T cells significantly decreased from baseline in PLHIV receiving pitavastatin for 12 weeks, as compared to placebo (− 0.27 vs. 0.02%; p=0.049 and − 0.23 vs. 0.23%; p=0.022, respectively).

Conclusions

Pitavastatin treatment increases basic FGF levels, and lowers HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells, and PD1+CD4+ T cells. Further study on the effects of pitavastatin on preventing cardiovascular diseases in PLHIV should be pursued.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Dyslipidemia, HIV infection, Inflammatory biomarker, Pitavastatin

Introduction

The use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) has evidently reduced opportunistic infection-related morbidity and mortality [1]. Despite undetectable plasma viral load, immune activation and inflammation persist in PLHIV receiving ART [2]. These are associated with an increased risk of non-AIDS related morbidities and mortality. In the era of ART, the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) was raised and become one of the leading causes of death in PLHIV [3]. PLHIV have an increased risk for CVD approximately 1.5-2 times compared to HIV-uninfected persons [4].

Protease inhibitors are currently recommended as alternative agents for first-, second-, and third-line antiretroviral regimens [5]. Among protease inhibitors, ritonavir-boosted atazanavir is not associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease [6, 7], in contrast to other agents [7, 8]. Newer classes of antiretroviral agents, for example integrase strand transfer inhibitors, have emerged and are preferred in the first-line antiretroviral regimens [5]. However, long-term cardiovascular disease risk associated with these agents have yet to be confirmed in large-scale studies [9]. Although ritonavir-boosted atazanavir is not associated with the increased risk of cardiovascular disease, ritonavir-boosted atazanavir has greater increases of cholesterol and triglyceride levels from baseline compared to unboosted atazanavir [10].

Statins possess pleiotropic anti-inflammatory activities in addition to lipid-lowering effects [11]. Many inflammatory markers were shown to be related with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), D-dimer, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) [12, 13]. Use of different statins has been shown to be associated with reduced biomarkers of inflammation/immune activation and endothelial dysfunction, although there were some discrepant results [11, 14]. Pitavastatin has less drug-drug interactions compared with other lipid-lowering agents [15]; therefore the drug benefits for the use in PLHIV receiving ART that has drug-drug interaction with other statins. Limited data are available regarding the anti-inflammatory effect of pitavastatin in HIV-infected individuals. We studied the effect of pitavastatin use in virologically-suppressed HIV-infected patients on atherosclerotic-associated inflammatory biomarkers.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

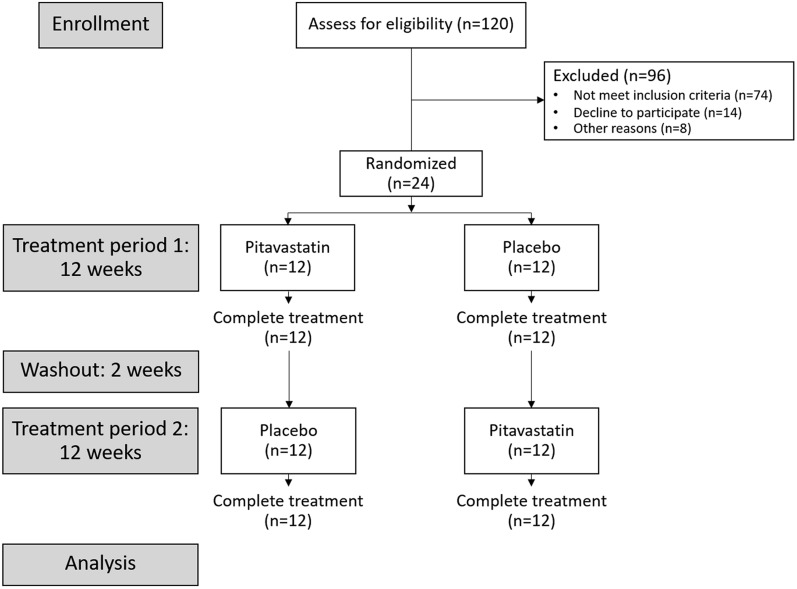

This study is a substudy of a randomized, double-blind, crossover study of 24 HIV-infected dyslipidemic patients receiving ritonavir boosted atazanavir (ATV/r) that was conducted to study safety and efficacy of pitavastatin for treatment of dyslipidemia (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02442700) [16]. Breifly, participants were assigned to receive 2 mg/day of pitavastatin or placebo for 12 weeks, followed by 2 weeks of washout period, and then 12 weeks of the other treatment arm (Fig. 1). At the enrollment and at the end of 12 weeks of each treatment arm, blood was collected for inflammatory marker study. Estimated 10-year cardiovascular disease risk was calculated by Thai CV risk score, a tool developed to predict a 10 year cardiovascular risk using data from Thai people, as recommended by Thai guidelines [17, 18] (Application available on App store: https://apps.apple.com/id/app/thai-cv-risk-calculator/id1564700992).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of subjects in the randomized crossover trial

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Clearance Committee on Human Right Related to Research Involving Human Subjects of the Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (MURA2014/18).

Immunophenotyping

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from study donors were isolated by gradient centrifugation using Histopaque® (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, US) as per manufacturer’s recommendation. Each sample was resuspended with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, US) and 90% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, US) and frozen before use. After PBMC collection had been complete, samples were thawed in complete medium (RPMI 1640 medium) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, US) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, US). PBMCs were stained with LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, US). Then, PBMCs were stained with fluorescence conjugated antibodies specific to protein surface markers, including PE/Cy5 anti-human CD25 (1:80), PE/Cy7 anti-human CD38 (1:80), APC/Cy7 anti-human CD4 (1:80), BV650 anti-human CD127 (1:80), Pacific blue anti-human CD3 (1:320), APC anti-human CD142 (1:160), FITC anti-human CD14 (1:40), PE-Texas Red anti-human CD16 (1:80), Alexa Fluor 700 anti-human CD8 (1:160) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, US), and PE anti-human programmed cell death-protein 1 (PD-1) (1:40) (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA), and eFluor 605NC anti human HLA-DR (1:40) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, US). All samples were examined via BD LSRFortessa (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.7.0 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, US). Each cell subpopulation was estimated in percentage from total PBMCs without dead cells, debris, and doublet.

Cytokine and chemokine levels

Levels of cytokines and chemokines in plasma samples were measured in duplicate by multiplex bead array assays using a Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 27-Plex Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α, eotaxin, basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage (GM)-CSF, IFN-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, platelet derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB), regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were analyzed in Bio-Plex Manager software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). In addition, hs-CRP levels were determined by a particle enhanced immunoturbidimetry assay (Rapid Labs, Colchester, Essex, UK) as per manufacturer’s recommendation.

Statistical analysis

Median, interquartile range (IQR), and frequency were used to describe patients’ characteristics. Changes of levels of cytokines and proportions of immune cell subsets from baseline were compared by Wilcoxon signed ranks test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, US), and GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, US).

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 24 participants were shown in Table 1 [16]. Breifly, the median (IQR) age was 46 (41–54) years, and 14 participants (58.3%) were men. Of the participants, 95.8% had undetectable plasma HIV viral load, and the median CD4 T cell count was 662 (559–827) cells/mm3. The median duration of ATV/r use was 36 (24–48) months. The median 10 year estimated cardiovascular diseases risk was 2.7 (1.9–5.4) percent.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

| Characteristics | n=24 |

|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 45.5 (41.0–54.0) |

| Male, % | 58.3 |

| CD4+ T cell count, cells/mm3 (median, IQR) | 661.5 (559.3–827.0) |

| Undetectable HIV viral load, % | 95.8 |

| Duration of ATV/r use, months (median, IQR) | 36 (24–48) |

| Comorbidities, % | |

| None | 50.0 |

| Dyslipidemia | 25.0 |

| Chronic HBV or HCV | 16.7 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors*, % | |

| <2 | 74.0 |

| ≥2 | 25.0 |

| 10-year CVD risk, % (median, IQR) | 2.7 (1.9–5.4) |

| Baseline lipid profiles, mg/dL (median, IQR) | |

| Total cholesterol | 242.5 (215.0–264.0) |

| LDL-cholesterol | 144 (127.0–160.0) |

| HDL-cholesterol | 41.0 (34.0–46.0) |

| Triglyceride | 190.0 (145.0–355.0) |

*Current smoking, systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or on antihypertensive drugs, HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dL, premature coronary heart disease in first-degree relative (age <55 years in male and <65 years in female), and age >45 years in male or >55 years in female

ATV/r atazanavir/ritonavir, CVD cardiovascular risk, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, HDL high-density lipoprotein, IQR interquartile range, LDL low-density lipoprotein

hs-CRP, chemokine and cytokine levels

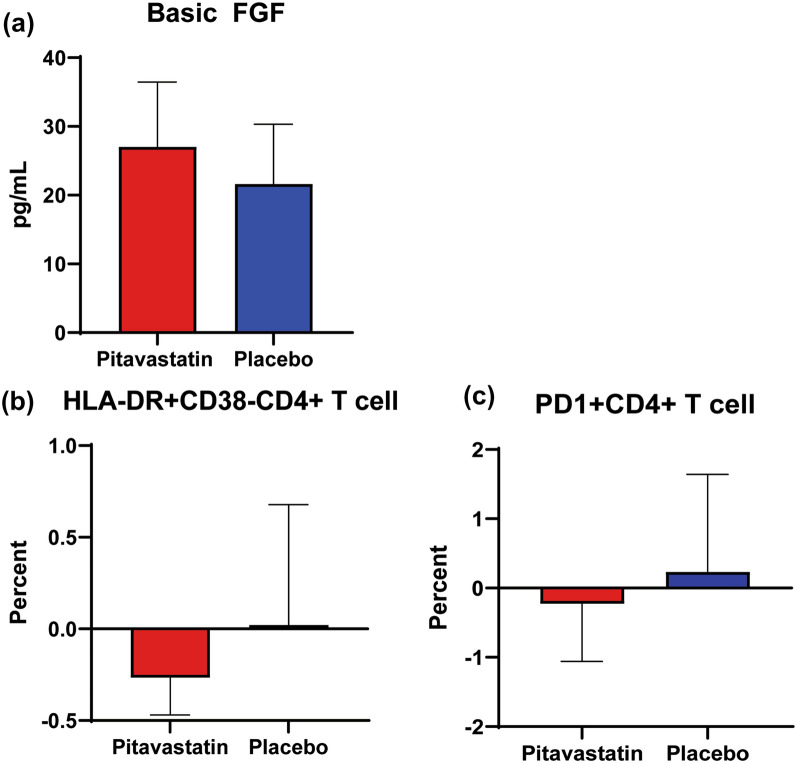

Pitavastatin did not have a significant effect on plasma levels of hs-CRP. A median change in levels of basic FGF at week 12 of pitavastatin treatment from baseline were significantly different compared to that after receiving placebo (27.1 vs. 20.5 pg/mL; p=0.023) (Fig. 2A). Change in level of IL-15 from baseline were increased after receiving placebo, but the difference of change after receiving pitavastatin vs. placebo did not reach statistically significance. Changes of levels of other cytokines from baseline were not different at week 12 after receiving pitavastatin vs. placebo (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Inflammatory markers that revealed significant difference of changes from baseline to week 12 of pitavastatin vs. placebo in PLHIV receiving ritonavir-boosted atazanavir; (A) basic FGF, (B) HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells, (C) PD-1+CD4+ T cells. Y axis shows median change from the baseline

Table 2.

Baseline and changes of cytokine levels from baseline to week 12 of pitavastatin treatment vs. placebo

| Cytokines | Baseline | Change from baseline after pitavastatin | Change from baseline after placebo | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | 2.01 (1.71 –2.42) | 1.28 (0.39–2.87) | 0.99 (0.30 –1.88) | 0.820 |

| IL-1ra | 153.80 (132.90–180.80) | 37.10 (− 13.40–81.50) | 33.10 (8.44 –105.00) | 0.865 |

| IL-2 | 9.51 (6.32–11.16) | 2.16 (0.49–5.54) | 1.74 (0.65–3.54) | 0.872 |

| IL-4 | 3.89 (3.46–4.70) | 1.82 (1.21–2.37) | 1.35 (1.08 –2.20) | 0.261 |

| IL-6 | 7.66 (6.55 –9.50) | 6.73 (1.00–33.3) | 9.29 (0.09 –26.40) | 0.966 |

| IL-7 | 20.59 (11.55–34.30) | − 0.32 (− 15.10–4.72) | 1.38 (− 12.70–11.70) | 0.560 |

| IL-8 | 23.87 (20.81–29.57) | 57.00 (18.50–89.70) | 53.6 (5.03–171.00) | 0.551 |

| IL-9 | 66.40 (53.63–76.46) | 42.1 (21.10–53.90) | 34.20 (14.80–66.00) | 0.922 |

| IL-10 | 14.38 (3.38–17.04) | 2.19 (0.00–10.30) | 2.36 (0.00 –10.50) | 0.958 |

| IL-12 | 19.24 (13.43–29.46) | 9.39 (1.16–14.80) | 8.94 (4.81–15.90) | 0.601 |

| IL-13 | 1.60 (1.16 –2.18) | 1.23 (0.01–2.26) | 1.06 (0.00–1.79) | 0.768 |

| IL-15 | 14.23 (11.49–19.67) | 0.00 (− 4.03–1.57) | 1.19 (− 2.34–3.14) | 0.086 |

| IL-17 | 211.20 (167.1 – 244.5) | 173.00 (85.10–219.00) | 129.00 (68.8–199.00) | 0.747 |

| Eotaxin | 90.88 (70.86 – 110.20) | 5.97 (− 6.60–17.70) | 8.76 (− 9.80 –17.90) | 0.790 |

| Basic FGF | 85.25 (75.04–98.90) | 27.10 (18.30–36.60) | 20.50 (11.60–29.00) | 0.023 |

| G-CSF | 70.84 (59.80–76.97) | 0.79 (− 11.40–10.80) | 4.90 (− 3.33 –8.48) | 0.622 |

| GM-CSF | 57.01 (48.31–66.63) | 8.67 (0.24–14.40) | 3.52 (0.00–13.00) | 0.223 |

| IFN-γ | 14.40 (14.40–74.01) | 0.00 (− 2.70–12.00) | 0.00 (0.00–34.30) | 0.269 |

| IP-10 | 613.40 (466.00–921.90) | 133.00 (17.30–201.00) | 103.00 (20.70–158.00) | 0.870 |

| MCP-1 | 121.70 (100.80–160.50) | − 18.00 (− 49.10 – 0.62) | − 29.8 (− 43.80–−7.81) | 0.520 |

| MIP-1α | 3.64 (1.00 –4.42) | 6.64 (3.80–14.80) | 6.21 (3.56–20.90) | 0.716 |

| MIP-1β | 443.90 (368.50–482.90) | 610.00 (188.00 –1618.00) | 762.00 (87.80–1702.00) | 0.368 |

| PDGF-BB | 409.70 (319.40–521.90) | 359.00 (240.00–443.00) | 305.00 (143.00–423.00) | 0.601 |

| RANTES | 7240.00 (5799.00–9174.00) | − 2626.00 (− 5815.00–−506.00) | −1226.00 (− 3419–236.00) | 0.107 |

| TNF-α | 52.70 (43.67–60.75) | 25.10 (6.94–56.60) | 21.90 (7.85-37.20) | 0.475 |

| VEGF | 103.20 (81.34–164.90) | 22.10 (− 12.10–47.90) | 23.20 (0.07 –54.70) | 0.331 |

| hs-CRP | 1.19 (1.00 –1.86) | 0.12 (− 0.21–0.67) | 0.17 (− 0.27 –0.78) | 0.596 |

Values are shown as median (interquartile range). Units of cytokines are pg/mL; unit of hs-CRP is mg/L

FGF fibroblast growth factor, G-CSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, GM-CSF granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IP-10 interferon-γ-induced protein 10, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MIP macrophage inflammatory protein, PDGF-BB platelet-derived growth factor BB, RANTES regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted, TNF tumor necrosis factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

Cellular immune profiles

For the study of cellular biomarkers, pitavastatin treatment did not have a significant effect on changes in the proportion of T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and monocytes (Table 3). However, pitavastatin treatment resulted in significant different changes in the proportion of HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells and PD-1+CD4+ T cells from baseline to week 12 of pitavastatin vs. placebo (− 0.27 vs. 0.02%; p=0.049, and − 0.23 vs. 0.23%; p=0.022, respectively) (Fig.2B, C).

Table 3.

Baseline and changes in the proportions of immune cell subsets from baseline to week 12 after pitavastatin treatment vs. placebo baseline

| Immune cell subsets (%) | Baseline | Change from baseline after pitavastatin | Change from baseline after placebo | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes | 55.50 (50.40–60.89) | − 2.10 (− 8.67–6.60) | −0.30 (− 7.50–16.00) | 0.241 |

| T cells | 38.70 (19.91–45.93) | 0.96 (− 9.07 –8.37) | 0.12 (− 14.80 –6.83) | 0.101 |

| CD4+ T cells | 19.72 (9.20–22.01) | − 0.78 (− 4.90–6.34) | 1.66 (− 2.98–9.32) | 0.134 |

| HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells | 0.84 (0.46–1.64) | − 0.07 (− 0.47–0.39) | 0.04 (− 0.24–0.88) | 0.205 |

| HLA-DR+CD38- CD4+ T cells | 1.37 (0.86–1.95) | − 0.27 (− 0.47–0.24) | 0.02 (− 0.35–0.68) | 0.049 |

| HLA-DR-CD38+CD4+ T cells | 8.28 (3.90–11.59) | − 0.35 (− 3.06–2.21) | 0.90 (− 1.24–5.45) | 0.073 |

| HLA-DR-CD38-CD4+ T cells | 6.08 (1.75–7.97) | 0.04 (− 1.12 – 2.65) | 0.66 (− 0.91–2.96) | 0.966 |

| PD-1+CD4+ T cells | 3.37 (1.07–4.27) | − 0.23 (− 1.06–0.79) | 0.23 (− 0.92–1.64) | 0.022 |

| Regulatory T cells | 0.76 (0.39–1.04) | 0.09 (0.00–0.42) | 0.23 (0.06 – 0.52) | 0.097 |

| CD8+ T cells | 17.79 (8.51 – 21.32) | − 0.61 (− 4.02–3.47) | 0.73 (− 3.96–5.20) | 0.252 |

| HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD8+ T cells | 2.93 (1.64–3.48) | − 0.53 (− 1.08–0.59) | − 0.34 (− 1.26–0.83) | 0.160 |

| HLA-DR+CD38-CD8+ T cells | 3.35 (2.38–5.01) | 0.11 (− 0.92–1.59) | 0.55 (− 0.50–1.76) | 0.364 |

| HLA-DR-CD38+CD8+ T cells | 2.66 (1.26–5.74) | − 0.41 (− 1.00–0.16) | 0.06 (− 0.72–1.33) | 0.145 |

| HLA-DR- CD38-CD8+ T cells | 5.07 (2.06–8.34) | 0.60 (− 1.35–3.04) | − 0.12 (− 0.93–1.74) | 0.703 |

| PD-1+CD8+ T cells | 2.88 (0.94 – 4.80) | − 0.17 (− 0.94 – 0.62) | − 0.01 (− 1.11–1.49) | 0.426 |

| Monocytes | 3.46 (2.66–4.11) | 1.07 (− 1.12 –1.64) | 0.61 (− 0.76–1.92) | 0.313 |

| Classical monocytes | 1.65 (0.90–2.71) | 0.72 (− 0.60–1.81) | 0.65 (− 0.40–2.18) | 0.569 |

| Intermediate monocytes | 0.08 (0.04–0.12) | − 0.01 (− 0.05–0.03) | 0.00 (− 0.03–0.05) | 0.966 |

| Nonclassical monocytes | 0.31 (0.20–0.47) | 0.03 (− 0.15 –0.) | 0.02 (− 0.11–0.17) | 0.326 |

| Patrolling monocytes | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.00 (− 0.01 –0.02) | 0.00 (− 0.01–0.02) | 0.490 |

Values are shown as median (interquartile range)

Discussion

We investigated the effects of pitavastatin on atherosclerotic-associated inflammatory biomarkers in PLHIV who had dyslipidemia and receiving ritonavir-boosted atazanavir. Although pitavastatin significantly lowered serum total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol [16], there were no significantly different change of hs-CRP from baseline to week 12 of pitavastatin vs. placebo. However, pitavastatin treatment resulted in different changes of basic FGF, HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells, and PD1+CD4+ T cells from baseline to week 12 of pitavastatin vs. placebo.

The INTREPID study compared the effects of pitavastatin (4 mg daily) versus pravastatin (40 mg daily) on markers of immune activation and arterial inflammation in PLHIV and revealed greater reduction in soluble CD14, oxidized LDL, and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase 2, which are markers of immune activation and arterial inflammation, in the pitavastatin arm at week 52 [19]. We did not investigate these markers. However, similar to findings in our study, their study demonstrated no change in the levels of IL-6 and hs-CRP after one year of pitavastatin treatment [19, 20]. Our work revealed statistically difference in change of basic FGF levels between pitavastatin treatment and placebo at week 12. Basic FGF improves myocardial perfusion in animal model [21]. We also found an increase of IL-15 levels in the participants after receiving placebo, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. IL-15 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is up-regulated in atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction [22]. Further studies with larger sample size and/or increased dose of pitavastatin should be performed. However, the use of 4 mg/day of pitavastatin was associated with more muscle complaints compared to the use of 1 mg/day dose [23].

Our results showed significantly different changes in the proportions of T cell subsets of HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells and PD-1+ CD4+ T cells from baseline to 12 week of pitavastatin vs. placebo. The previous study demonstrated significant reductions in HLA-DR+CD4+, HLA-DR+CD8+, and HLA-DR+CD38+ T cells after receiving 8 weeks of high dose atorvastatin (80 mg daily) [24]. We also found reductions in HLA-DR+ in CD4+ T cells, but only the HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cell subpopulation yielded statistically significant difference. A previous study showed that an increased HLA-DR+ T cells in hypercholesterolemic subjects as well as in patients with chronic stable angina and acute myocardial infection compared with controls [25]. HLA-DR is recognized as a marker of T cell activation. Therefore, pitavastatin treatment might lower T cell activation and hence reduce immune activation in PLHIV. PD-1 is one of the immunosuppressive costimulatory molecules, which mediates an inhibitory effect [26]. PD-1 is up-regulated on HIV-specific CD4+ T cells and its expression level correlated with plasma viremia and inversely with CD4+ T cell counts [27]. PD-1 is a marker of T cell exhaustion, and can be found during chronic infection [28]. T cells from human atherosclerotic plaques were found to express high levels of PD-1 [29]. Okoye and co-workers previously demonstrated the reduction of co-inhibitor receptor expression, including PD-1, after atorvastatin treatment [30]. This suggested the role of statin in restoring T cell function. Taken together, this study supported the decreased of some atherosclerotic-associated inflammatory markers after pitavastatin treatment.

The strength of our study included the double-blind, crossover study design which could minimize the biases. However, we accepted the limitations of the small sample size, and the short duration of the washout period. Some independent markers of cardiovascular disease-related mortality, i.e., sCD14, D-dimer, and fibrinogen, were not studied. Further, the short duration of follow-up did not allow for the detection of clinical outcome of cardiovascular events. A large prospective trial, for example, Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) [31], that determines the effect of long-term statin use in PLHIV on major adverse cardiovascular events would be helpful to answer this question.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that pitavastatin treatment, in addition to lipid lowering effect, could lower some of the atherosclerotic-associated cellular markers, including the proportions of HLA-DR+CD38-CD4+ T cells, and PD-1+CD4+ T cells. We also found an increased levels of basic FGF, which has atherosclerotic-protective effects. Further study on the effects of pitavastatin on preventing cardiovascular diseases in PLHIV is warranted.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participants in this study.

Abbreviations

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- ATV/r

Atazanavir/ritonavir

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- G-CSF

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

- GM-GSF

Granulocyte mocrophage-colony stimulating factor

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IFN-γ

Interferon gamma

- IL

Interleukin

- IP-10

Interferon gamma-induced protein 10

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MIP-1α

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha

- MIP-1β

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PD-1

Programmed cell death-protein 1

- PDGF-BB

Platelet derived growth factor BB

- PLHIV

People living with HIV

- RANTES

Regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Author contributions

Conceptulization: SK, BT, AP. Data curation: AW, AP. Methodology: SK, BT, AP. Formal analysis: AP. Funding acquisition: AP. Investigations: AW, SK, AP. Project administration: SK. Writing—original draft: SSr, AP. Writing—review and editing: SSr, SSu, SK, BT, AP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Dr Prasert Prasarttong-Osoth Research Grant from the Medical Association of Thailand. The funding body had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Clearance Committee on Human Right Related to Research Involving Human Subjects of the Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (MURA2014/18).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lederman MM, Funderburg NT, Sekaly RP, Klatt NR, Hunt PW. Residual immune dysregulation syndrome in treated HIV infection. Adv Immunol. 2013;119(51):83. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407707-2.00002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paiardini M, Muller-Trutwin M. HIV-associated chronic immune activation. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):78–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinstein MJ, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, Longenecker CT, Hsue P, So-Armah K, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular mortality for HIV-infected adults in the United States: 1999 to 2013. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(2):214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosepele M, Molefe-Baikai OJ, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Benefits and risks of statin therapy in the HIV-infected population. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018;20(8):20. doi: 10.1007/s11908-018-0628-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panel of Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv. Accessed 24 Jan 2023.

- 6.Monforte A, Reiss P, Ryom L, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, De Wit S, et al. Atazanavir is not associated with an increased risk of cardio- or cerebrovascular disease events. AIDS. 2013;27(3):407–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b2ef1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryom L, Lundgren JD, El-Sadr W, Reiss P, Kirk O, Law M, et al. Cardiovascular disease and use of contemporary protease inhibitors: the D:A: D international prospective multicohort study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(6):e291–e300. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worm SW, Sabin C, Weber R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with HIV infection exposed to specific individual antiretroviral drugs from the 3 major drug classes: the data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs (D:A:D) study. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(3):318–30. doi: 10.1086/649897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neesgaard B, Greenberg L, Miro JM, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Wandeler G, Smith C, et al. Associations between integrase strand-transfer inhibitors and cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: a multicentre prospective study from the RESPOND cohort consortium. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(7):e474–e85. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosn J, Carosi G, Moreno S, Pokrovsky V, Lazzarin A, Pialoux G, et al. Unboosted atazanavir-based therapy maintains control of HIV type-1 replication as effectively as a ritonavir-boosted regimen. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(7):993–1002. doi: 10.3851/IMP1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckard AR, McComsey GA. The role of statins in the setting of HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(3):305–12. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ammirati E, Moroni F, Norata GD, Magnoni M, Camici PG. Markers of inflammation associated with plaque progression and instability in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Med Inflamm. 2015;2015:718329. doi: 10.1155/2015/718329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sethwala AM, Goh I, Amerena JV. Combating inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30(2):197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longenecker CT, Eckard AR, McComsey GA. Statins to improve cardiovascular outcomes in treated HIV infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujino H, Yamada I, Shimada S, Yoneda M, Kojima J. Metabolic fate of pitavastatin, a new inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase: human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes involved in lactonization. Xenobiotica. 2003;33(1):27–41. doi: 10.1080/0049825021000017957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wongprikorn A, Sukasem C, Puangpetch A, Numthavej P, Thakkinstian A, Kiertiburanakul S. Effects of pitavastatin on lipid profiles in HIV-infected patients with dyslipidemia and receiving atazanavir/ritonavir: a randomized, double-Blind, crossover study. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Heart Association of Thailand Uncer the Royal Patronage of H.M. the King. thai chronic coronary syndrome guidelines 2021. 2022. http://www.thaiheart.org/images/introc_1646981507/Thai%20Chronic%20Coronary%20Syndromes%20Guidelines%202021.pdf. Accessed 3 Jan 2023.

- 18.The Royal College of Physicians of Thailand. 2016 clinical practice guideline on pharmacologic therapy of dyslipidemia for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention 2017. http://www.thaiheart.org/images/column_1487762586/2016%20RCPT%20Dyslipidemia%20Clinical%20Practice%20Guideline.pdf. Accessed 3 Jan 2023.

- 19.Toribio M, Fitch KV, Sanchez L, Burdo TH, Williams KC, Sponseller CA, et al. Effects of pitavastatin and pravastatin on markers of immune activation and arterial inflammation in HIV. AIDS. 2017;31(6):797–806. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aberg JA, Sponseller CA, Ward DJ, Kryzhanovski VA, Campbell SE, Thompson MA. Pitavastatin versus pravastatin in adults with HIV-1 infection and dyslipidaemia (INTREPID): 12 week and 52 week results of a phase 4, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, superiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(7):e284–e94. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domouzoglou EM, Naka KK, Vlahos AP, Papafaklis MI, Michalis LK, Tsatsoulis A, et al. Fibroblast growth factors in cardiovascular disease: The emerging role of FGF21. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309(6):H1029–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00527.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo L, Liu MF, Huang JN, Li JM, Jiang J, Wang JA. Role of interleukin-15 in cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(13):7094–101. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taguchi I, Iimuro S, Iwata H, Takashima H, Abe M, Amiya E, et al. High-dose versus low-dose pitavastatin in Japanese patients with stable coronary artery disease (REAL-CAD): a randomized superiority trial. Circulation. 2018;137(19):1997–2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganesan A, Crum-Cianflone N, Higgins J, Qin J, Rehm C, Metcalf J, et al. High dose atorvastatin decreases cellular markers of immune activation without affecting HIV-1 RNA levels: results of a double-blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(6):756–64. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ammirati E, Cianflone D, Vecchio V, Banfi M, Vermi AC, De Metrio M, et al. Effector memory T cells are associated with atherosclerosis in humans and animal models. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1(1):27–41. doi: 10.1161/xJAHA.111.000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patsoukis N, Wang Q, Strauss L, Boussiotis VA. Revisiting the PD-1 pathway. Sci Adv. 2020;6(38):abd2712. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443(7109):350–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(8):486–99. doi: 10.1038/nri3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez DM, Rahman AH, Fernandez NF, Chudnovskiy A, Amir ED, Amadori L, et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1576–88. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0590-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okoye I, Namdar A, Xu L, Crux N, Elahi S. Atorvastatin downregulates co-inhibitory receptor expression by targeting Ras-activated mTOR signalling. Oncotarget. 2017;8(58):98215–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grinspoon SK, Fitch KV, Overton ET, Fichtenbaum CJ, Zanni MV, Aberg JA, et al. Rationale and design of the randomized trial to prevent vascular events in HIV (REPRIEVE) Am Heart J. 2019;212:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.