Abstract

Zebrafish have emerged as a major model organism to study vertebrate reproduction due to their high fecundity and external development of eggs and embryos. The mechanisms through which zebrafish determine their sex have come under extensive investigation, as they lack a definite sex-determining chromosome and appear to have a highly complex method of sex determination. Single-gene mutagenesis has been employed to isolate the function of genes that determine zebrafish sex and regulate sex-specific differentiation, and to explore the interactions of genes that promote female or male sexual fate. In this review, we focus on recent advances in understanding of the mechanisms, including genetic and environmental factors, governing zebrafish sex development with comparisons to gene functions in other species to highlight conserved and potentially species-specific mechanisms for specifying and maintaining sexual fate.

Keywords. Sex determination, RNA binding protein, Ovary, Testis, Genetics

Introduction

Perpetuation of the species in sexually reproducing organisms depends on specification and sexual differentiation of the gametes. In hermaphroditic species, an individual can produce both male and female gametes, but in many species, an individual’s sex is determined during development and thereafter that individual can produce either female (oocytes) or male (sperm) gametes, that when united through mating will produce the next generation. Therefore, specification of an individual’s fate as either female or male is a crucial lifetime event. Not surprisingly, many of the key genes and pathways that govern sex determination and development of the gametes are evolutionarily conserved. Surprisingly, the upstream activators and initial determinants of sexual fate as well as the immediate downstream events, including how shared regulators are deployed mechanistically can vary widely among species (reviewed in [1–4]). Yet, despite these differences in early steps of specification, comparisons among systems indicate that, where examined thus far, the mechanisms tend to converge on shared regulatory cassettes.

Zebrafish are widely utilized as a model organism to study a variety of organ systems and biological pathways. The process through which zebrafish determine their sex, however, is still not fully understood. While many genes implicated in sex development pathways have a conserved role among vertebrates including zebrafish and will be detailed below, the initial trigger that governs the decision to develop as male or female remains a mystery. In this review, we detail recent insights into the mechanisms of sex determination in zebrafish and discuss potential candidates of upstream determinants of sexual fates in zebrafish. Where possible, comparisons to sex-determining gene functions in other species are made to highlight conserved and potentially species-specific mechanisms for specifying and maintaining sexual fate.

Zebrafish germline development: from primordial germ cells to differentiated adult

Sex determination in zebrafish, as in many organisms, depends on the sex identity of the germ cells which instruct specification of the somatic gonad cells. The somatic gonad cells thereby produce appropriate sex hormones which then instruct sex-specific differentiation of the somatic cells in the rest of the body [5].

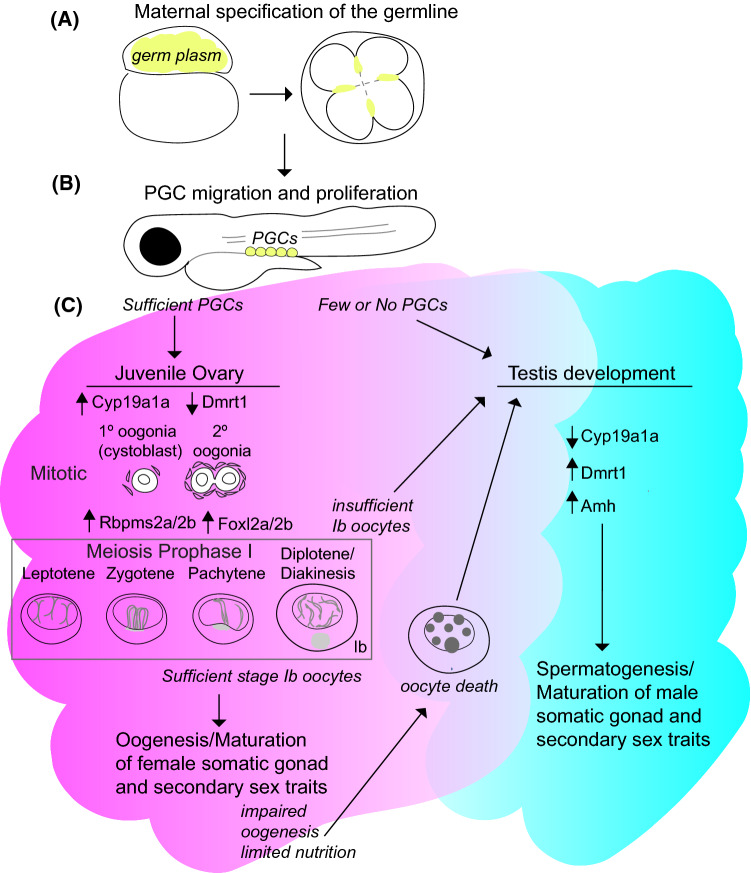

The primordial germ cells (PGCs) in zebrafish are maternally specified and can be detected by accumulation of germ plasm at the cleavage furrow of early embryos (Fig. 1A). These cells begin to migrate during gastrulation and ultimately gather in two groups on either side of the notochord, at the site of the future gonad, by 1-day post-fertilization (dpf) [6] (Fig. 1B). As they migrate, PGCs must be protected from various signals that could trigger differentiation into somatic cells. Dead end protein (Dnd) plays a major role in maintaining PGCs, and loss of Dnd leads to reprogramming of the PGCs to somatic cell fates, loss of germ cells, and male only development [7–9].

Fig. 1.

Overview of germline specification and sexual differentiation. (A) The zebrafish germline is specified by inheritance of maternal germ plasm (yellow) which can be seen at the animal pole and in select cleavage furrows of the early embryo (cartoon is animal pole view of 4-cell stage). (B) After specification, PGCs proliferate and migrate to the gonad anlage. (C) If PGC numbers are limiting then the developing fish will begin differentiation as a male. If sufficient PGCs are present, then a bi-potential ovary develops and meiosis I and progression of oogenesis commences through diplotene arrest at the end of prophase I. If adequate stage Ib oocytes are produced, then the somatic gonad and oocyte differentiate further but if there are insufficient stage Ib oocytes, male promoting factors increase in abundance and the juvenile ovary is replaced by a male gonad. Even after the ovary matures, sustained communication between the germline and the somatic gonad cells are required to maintain the expression of pro-female factors and female fate and to prevent oocyte death and transdifferentiation as a male

Over the next week of development, the PGCs do not appear to proliferate; however, during this time, epigenetic changes involving chromatin and transcriptome programming regulate PGC fate, and activation of piRNA pathways take place [10, 11]. Maternally derived transcripts, such as vasa and nanos3, can be detected through the first week of development and are thought to play important roles in PGC survival [6, 12, 13].

The onset and mechanisms of the somatic gonad specification are not clear; however, the somatic gonad is histologically evident around 5 dpf [14]. Thereafter, both the germ cells (GCs) and somatic gonad cells begin to proliferate at around 7–10 dpf [15]. At this time, germ cells undergo cystogenesis, or coordinated incomplete mitotic divisions, prior to initiating meiosis [16]. Through this process, GCs form a structure called a cystoblast in which GCs are connected by ring canals. The RNA-binding protein Dazl is required for germline cyst development, germ cell proliferation, and germline stem cell formation. Loss of dazl leads to failure of sexual development and sterility [16].

The gonad is undifferentiated and is bi-potential until about 12 dpf, expressing genes involved in both male and female development [5, 15, 17]. Around 13–14 dpf, the development of early-stage oocytes, or gonocytes, give the early undifferentiated gonad an ovary-like appearance although it remains bi-potential (Fig. 1C) [18]. The gonad then continues to grow due to continued proliferation of both germ cells and somatic cells. The germ cell proliferation that occurs in the second week of development appears to be essential to gonadal differentiation, with high PGC number leading to female fate (Fig. 1C) [19].

Sexual differentiation in the zebrafish first becomes apparent at about 20–25 dpf. At 19–25 dpf, the undifferentiated gonad contains stage 1A and early 1B oocytes which have not yet progressed through diplotene of meiosis I (Fig. 1C) [20, 21]. Thereafter in differentiating males, stage I oocytes undergo apoptosis and stage 1B oocytes develop in females (Fig. 1C) [21]. As is thought to be the case in mammals where changes in cell cycle state are among the earliest detectable differences between eventual male and female fetal germ cells, cell cycle regulators may play a sexually dimorphic role in meiotic regulation, and thereby contribute to sex differentiation [22]. Consistent with this notion, zebrafish cdk21 (cyclin-dependent kinase 21) is expressed in stage I oocytes, which are crucial for maintenance of female fate in zebrafish, and only later becomes enriched in male germ cells [23].

Between 25 and 45 dpf, the gonad undergoes a period of “transitioning” from a juvenile gonad with an ovary-like appearance to a mature ovary in females or testis in males [21]. During this transitional period, the zebrafish gonad retains the potential to generate female and male germ cells [18]. In females, gonocytes continue to develop into oocytes which drive differentiation of the gonad into a mature ovary (Fig. 1C). Beginning at 26 dpf, late-state IB oocytes which have progressed past the diplotene stage of meiosis I can be seen in wild-type ovaries, whereas mutants for fancl or fancd1(brca2), which are important for the development of oocytes through meiosis, failed to progress normally beyond diplotene of meiosis I [20]. In males, gonocytes differentiate as spermatogonia and somatic gonad cells adopt male fates, Sertoli and Leydig cells, as spermatogenesis ensues. Expression of amh and declining cyp19a1a in some wild-type males and fancl or fancd1 mutants indicates that individuals in both groups can begin to differentiate along the male pathway by 26 dpf [20, 24, 25]. That all fancl and fancd1 mutants had immature testes by 32 dpf, in contrast to wild-type gonads, which were either immature ovaries or immature testes, indicated a key role for Fanconi anemia genes in maintenance or differentiation of female fates [20, 24, 25]. The presence of apoptotic oocytes in fancl and fancd1 mutants, suppression of oocyte loss by mutation of tp53 in fancl mutants supported a model wherein oocyte loss in Fanconi anemia gene mutants is due to activation of a Tp53-mediated meiotic checkpoint [20, 24, 25].

As expected based on cdk21 expression in stage I oocytes, loss of cdk21 function causes zebrafish to develop exclusively as males with hypoplastic testis due to defects in spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation [23]. How cdk21 and other cell cycle regulators contribute to sexual differentiation remains to be further elucidated, but in zebrafish female fate must be actively maintained by the germline to prevent transdifferentiation.

Genetics of sex determination

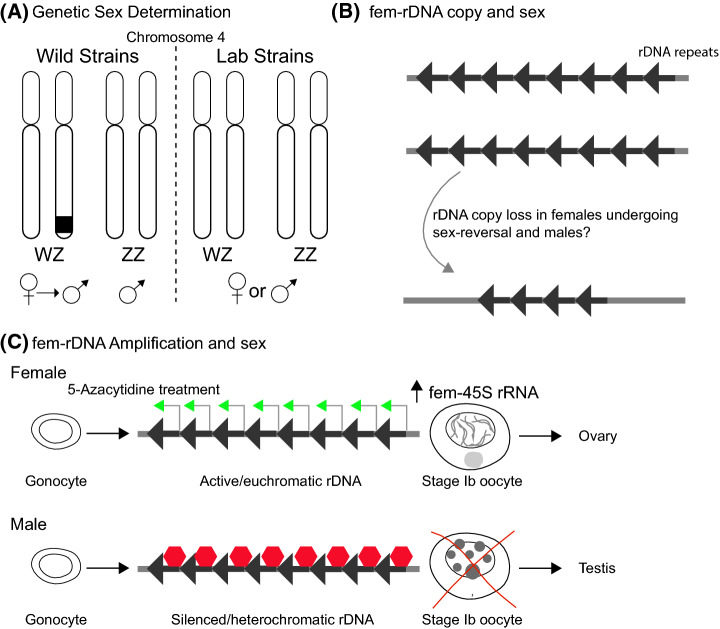

Genetic determination of sexual fate among teleosts is complex and variable. Zebrafish in the wild have been found to utilize a WZ/ZZ chromosomal method of sex determination, with a major sex determinant identified on chromosome 4 [26] (Fig. 2A). Sex determination among wild strains appears to be female-heterogametic, with ZZ chromosomes leading to male fate while ZW conveys female fate; however, ZW individuals can develop as male, known as pseudo-males, under certain conditions [26] (Fig. 2A). It remains to be determined if female fate is determined by a specific factor on the W chromosome or instead if male is determined by increased abundance of a factor on Z. Domesticated zebrafish, on the other hand, lack sex chromosomes and have a polygenic mechanism of sex determination. Studies utilizing genome-wide association methods to characterize genes involved in sex determination each found different loci among wild-type lines [27–30] (Fig. 2A). Thus, the genes or extent to which specific alleles contribute to sex determination may vary among genetic strains of zebrafish, but this remains to be determined.

Fig. 2.

Sex determination in zebrafish. (A) Zebrafish strains in the wild have a WZ and ZZ sex determination system with heterozygous (WZ) females that can adopt male fates. (B) An 11.5 kB repeat encoding a maternal-specific 45S rDNA resides on chromosome 4 and overlaps the sex-determining region on chromosome 4 of wild strains and is (C) amplified in stage Ib oocytes—the stage required to sustain female development. Treating zebrafish with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-Azacytidine, results in female sex bias. Thus, female fate may be induced by amplification and or stabilization of fem-rRNA and oogenesis, while demethylation and silencing of this site, and potentially others, could promote oocyte loss and male fate. Red hexagons indicate silencing and repression

Evidence from analysis of DNA methylation in the germline indicates that, in contrast to the global hypomethylation seen in mammals (reviewed in [31]), no global erasure of DNA methylation occurs at any stage of zebrafish germline development analyzed [32, 33]. However, one study identified amplification and demethylation of a 11.5kB repeat region that overlaps with the sex determination loci reported on zebrafish chromosome 4 [29, 32] (Fig. 2B). That this region encodes a maternal-specific 45S ribosomal DNA, called fem-rDNA, that is amplified specifically during expansion of stage IB oocytes, which are required for female fate, occurs makes it a compelling factor in zebrafish sex determination [19, 24, 32, 34, 35] (Fig. 2C). Sexually dimorphic regulation of fem-rDNA transcription, stability and/or repeat numbers by sex-determining regulatory modules or non-genetic and epigenetic factors that modulate accessibility and transcription of fem-rDNA may underlie the sex-determination system in domesticated zebrafish lab strains, but this compelling model remains to be verified.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis has made it possible to analyze the role of a variety of genes in zebrafish sex determination and differentiation [36] (Table 1). Major genetic determinants that have been investigated include transcription factors, ligands, sex hormones, aromatases, and cell cycle factors, among others, yet we still do not know what factor or factors trigger sex determination in zebrafish.

Table 1.

Genes implicated in sexual differentiation or maintenance and their functions

| Gene | Protein/product type | Primordial germ cell numbers, migration, maintenance | Germline stem cell specification | Germline stem cell maintenance | Germ cell mitosis/proliferation | Bipotential gonad | Stage IB oocytes | Progression beyond diplotene | Oocyte development/maintenance | Follicle development/female somatic gonad | Spermatogenesis | Male somatic gonad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dnd | RNA-binding protein | Morpholino [7, 8, 9] | ||||||||||

| vasa/ddx4 | RNA-helicase | Transgenesis (Krovel et al. 2004); ENU mutagenesis premature stop codon [12] | ||||||||||

| nanos2 | RNA-binding protein | CRISPR premature stop codon, transgenesis [78] | ||||||||||

| nanos3 | RNA-binding protein | Morpholino [13]; ENU mutagenesis premature stop codon [77, 83] | ENU mutagenesis premature stop codon [77, 83] | |||||||||

| dazl | RNA-binding protein | ZFN premature stop codon, CRISPR premature stop codon, protein truncation [16] | ||||||||||

| cdk21 | Cell cycle regulator | ENU mutagenesis protein kinase disruption, CRISPR premature truncation [23] | ENU mutagenesis protein kinase disruption, CRISPR premature truncation [38] | ENU mutagenesis protein kinase disruption, CRISPR premature truncation [38] | ||||||||

| dmrt1 | Transcription factor | TALEN protein truncation/loss of function and reduction of function [38]; CRISPR premature termination codons [39] | TALEN protein truncation/loss of function and reduction of function [38]; CRISPR premature termination codons [39] | |||||||||

| amh | Hormone | CRISPR premature termination codon [39]; CRISPR and TALEN premature stop codon [40] | CRISPR and TALEN premature stop codon [40] | CRISPR premature termination codon [39]; CRISPR and TALEN premature stop codon [40] | CRISPR premature termination codon [39], CRISPR and TALEN premature stop codon [40] | CRISPR premature termination codon [39], CRISPR and TALEN premature stop codon [40] | ||||||

| bmpr2a | Ligand | CRISPR deletion [41] | CRISPR deletion [41] | CRISPR deletion [41] | ||||||||

| gdsf | Growth factor | TALEN premature stop codon [42] | TALEN premature stop codon [42] | |||||||||

| ar | Ligand | CRISPR peptide truncation [47]; CRISPR premature stop codon [48] | CRISPR peptide truncation [47], CRISPR premature stop codon [48] | CRISPR peptide truncation [47], CRISPR premature stop codon [48] | ||||||||

| cyp19a1a | Enzyme | TALEN loss of function/premature stop codon [21], TALEN and CRISPR indel mutations [49], TALEN open reading frame shift [50], TALEN and CRISPR indel mutations [51], TALEN loss of function/premature stop codon [52] | TALEN loss of function/premature stop codon [21], TALEN and CRISPR indel mutations [49], TALEN open reading frame shift [50], TALEN and CRISPR indel mutations [51], TALEN loss of function/premature stop codon [52] | |||||||||

| rbpms2 | RNA-binding protein | CRISPR in-frame deletion, truncated protein, RNP disruption [52, 60] | ||||||||||

| ddx5 | RNA-helicase | TALEN functional protein disruption [68] | ||||||||||

| zar1 | RNA-binding protein | TALEN and CRISPR premature stop codon [71] | ||||||||||

| nedd8 | Ubiquitin-like protein modifier | CRISPR deletion [72] | CRISPR deletion [72] | |||||||||

| prmt5 | Methyl transferase | CRISPR protein truncation [75] | CRISPR protein truncation [75] | |||||||||

| foxl2a/foxl2b | Transcription factor | TALEN frameshift or nonsense mutation protein disruption [63] | TALEN frameshift or nonsense mutation protein disruption [63] | |||||||||

| wnt4a | Ligand | Transgenesis [98], ENU premature stop codon; CRISPR translational frameshift [99] | ||||||||||

| bmp15 | Ligand | TALEN frame-shift deletion/loss of function [21] | TALEN frame-shift deletion/loss of function [21] | |||||||||

| nr0b1 | Ligand | TALEN open reading frame shift [113] | TALEN open reading frame shift [113] | |||||||||

| fgf24 | Ligand | CRISPR [15] |

Mutual antagonism governs sexual fate

In many metazoans, transcriptional regulators with a double-sex- and mab-3-related DNA-binding domain (DM domain) are essential to sexual development [37]. As in other vertebrates including other fish, birds, and mammals, dmrt1 (double-sex- and mab-3-related transcription factor 1) plays a major role in zebrafish sexual differentiation and male germ cell development, because the majority of dmrt1 mutants develop as females, with some developing as sterile males with testicular dysgenesis [38, 39]. Amh, the gene that encodes anti-Mullerian hormone, limits germ cell proliferation, promotes maturation of gametes, and plays a key role in regulating development of gonadal somatic genes in zebrafish [39, 40]. Similarly, loss of amh leads to a female-biased sex ratio with testicular developmental defects in males rendering them sterile by 6 mpf, but unlike loss of dmrt1 leads to gonadal hyperplasia in both male and female amh mutants [39, 40]. While Amh is key in regulating reproductive duct development in mammals, both male and female zebrafish mutants had functional sex ducts indicating that redundant factors contribute to duct formation in zebrafish or that distinct mechanisms mediate duct formation [40]. Zebrafish lack the cognate type II receptor for Amh (Amhr2), the major receptor through which Amh acts in most animals; however, the bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II a (Bmpr2a) was recently identified as a major Amh signaling target in zebrafish. Specifically, Bpmr2a mutants phenocopied all amh mutant phenotypes, and double mutants for both bmpr2a and amh were indistinguishable from single mutants, indicating that Bmpr2a fulfills the role of the Amhr2 receptor in zebrafish [41]. Like Amh, Gsdf (gonadal soma-derived factor) which is expressed in gonadal somatic cells of zebrafish, plays an important role in follicle maturation in females [42]. amh and gsdf, both members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family, appear to act non-redundantly in the same pathway, as both male and female double mutants had similar phenotypes to single mutants for either gene [40]. Because of their similar phenotypes and because TGF-β signaling is mediated by a tetrameric ligand-and-tetrameric receptor complex, wherein two dimers of ligand activate a heterodimeric receptor complex, it is likely that either a heterodimer of Amh and Gdf9 or a complex consisting of a homodimer of Gdf9 ligands plus a homodimer of Amh ligands signals non-canonically through Bmpr2a instead of through the Amhr2, which zebrafish lack (reviewed in [43–46]. Elevated amh in gdf9 mutants and reciprocally elevated gdf9 in amh mutants indicates that upregulating either ligand is not sufficient to compensate for loss of either ligand, thus favoring a heterodimer paradigm.

The androgen receptor gene (ar) is important for spermatogenesis and ovary maintenance in zebrafish [47]. The majority of ar mutants develop as females, and those with testes exhibit female secondary sex characteristics, indicating androgen receptor is not required for the gonad to differentiate as testis but is likely required for paracrine signaling to promote development of male secondary sex traits [48]. AR also plays a role in regulating expression of sexually dimorphic genes. In testes of ar mutant fish, female-associated genes cyp19a1a and foxl2a were upregulated, while in ovaries of mutant fish, male-determinant genes amh and dmrt1 were upregulated [48]. Consequently, both male and female ar mutants have reduced fertility [47, 48].

Cyp19a1a, the gene that encodes for the aromatase enzyme regulating the final step in estrogen production, is essential for establishment and maintenance of female fate. Cyp19a1a mutants develop exclusively as fertile males [21, 49, 50]. Although these studies found that cyp19a1a mutants failed to develop an ovary-like bi-potential gonad, one study reported that the undifferentiated state persisted and testis development was delayed in mutants, while another reported that early oocytes prematurely underwent apoptosis and sperm maturation occurred earlier in mutants compared to controls [21, 50]. It is unclear if these differences are due to the different alleles examined, differences in genetic background, or different interpretations of the data. In any case, males lacking cyp19a1a are fertile. Recent studies examining the effects of mutations in multiple sex-determining or sex-differentiating genes to determine their interdependence provided further evidence that cyp19a1a is required to promote the bi-potential state by antagonizing the male promoting factor dmrt1 as double mutant gonads lacking both cyp19a1a and dmrt1 contain follicles and oocytes that develop up to the pre-vitellogenic stage [51]. The dmrt1;cyp19a1a double mutants have either early oocytes or testis-like cells [52]. This indicates that cyp19a1a delays testis differentiation, is necessary for female fate, and although dispensable for early folliculogenesis, cyp19a1a and presumably estrogen are required for vitellogenic oocyte progression and development of advanced follicles [51, 52]. Whether the targets of cyp19a1a required to establish the bi-potential phase and those that promote oocyte progression and maintenance are shared or specific to each stage remains to be determined, but the genetic data thus far indicate that the early but not later role involves antagonism of Dmrt1.

As is thought to be the case in mammals where changes in cell cycle state are among the earliest detectable differences between eventual male and female fetal germ cells [22], cell cycle regulators may play a sexually dimorphic role in meiotic regulation, and thereby contribute to sex differentiation. Similarly, germ cells and oocytes in medaka and sticklebacks have a feminizing property on gonadogenesis, even when sex chromosomes are present, such that germ cell numbers correlate with gonad sex—individuals with plentiful germ cells develop as females while those with few germ cells take a male fate underscoring the importance of germ cell proliferation to female fate in these fish [53–58]. In zebrafish, while cdk21 (cyclin-dependent kinase 21) expression is enriched in male germ cells, it seems to promote female fate as well as male differentiation. Mutants develop exclusively as males but with hypo-plastic testis due to defects in spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation [23]. How cdk21 contributes to female differentiation is not known, but cdk21 is expressed in early oocytes of the stage known to be crucial for maintenance of female fate in zebrafish.

RNA regulation in sexual fate determination and differentiation

RNA-binding proteins are known to be essential post-transcriptional regulators of germline and oocyte development [59]. RNA-binding protein with multiple splicing (Rbpms2) was recently identified as an essential factor for female fate in zebrafish [60]. RBPMS is conserved in vertebrates and exists as two paralogs, RBPMS and RBPMS2 in a number of vertebrates including humans, and as Hermes in Xenopus [61, 62]. Zebrafish contain three homologs: rbpms1 (homolog of vertebrate rbpms), rbpms2a and rbpms2b (duplicated homologs of vertebrate rbpms2), with rbpms2a and rbpms2b expressed throughout oocyte development [60]. Zebrafish rbpms2a/2b were found to be most closely related among the zebrafish homologs to Xenopus hermes [60]. Rbpms2a and Rbpms2b were determined to be functionally redundant for female fate, as mutants for either rbpms2 gene lacked apparent phenotypes, but double mutants for rbpms2a and rbpms2b (rbpms2DM), on the other hand, developed exclusively as fertile males [60]. Failure to establish female fate was not due to deficiencies in establishment or proliferation of PGCs, and although male differentiation occurred earlier in rbpms2DMs than in siblings, similar to reports for cyp19a1a, rbpms2DMs establish a juvenile ovary but the oocytes fail to reach diplotene (stage II) [49, 51, 52, 60]. Consequently, no definitive ovary formed, even when Tp53-mediated apoptosis was eliminated, and rbpms2DMs eventually resolve as fertile males, like cyp19a1a mutants [49, 51, 52, 60]. These findings support a role for Rbpms2 in promoting female fate rather than simply maintaining it.

As an RNA-binding protein, Rbmps2 likely regulates female fate by promoting translation of female factors, repressing translation of male factors, or a combination of the two. Consistent with a role for Rbpms2 in repressing male factors, Rbpms2-binding sites were identified in the 3’utr of dmrt1 mRNA [52]. However, analysis of triple mutants lacking rbpms2a, rbpms2b, and dmrt1 indicated that loss of Dmrt1 was not sufficient to restore female fates in the absence of Rbpms2 function [52]. This is unique from the interaction between dmrt1 and cyp19a1a and suggests that a key to male differentiation is elimination of Rbpms2, which is necessary for the establishment of female fate through a mechanism separate from or in addition to repression of dmrt1. Because of the differences between the cyp19a1a and rbpms2DM phenotypes, both in the presence and absence of dmrt1, Rbpms2 likely acts after or in parallel to cyp19a1a, which establishes the bi-potential state, and upstream of yet to be identified regulators of female fate.

Unlike the feminizing factors discussed earlier, female fate cannot be prolonged or recovered when Rbpms2 is absent, demonstrating an essential role for this RNA-binding protein as a gatekeeper of sex determination and plasticity, because females maintain the capacity to switch sex in zebrafish [21, 63]. Investigation of the interaction between Rbpms2 and its target RNAs will reveal the zebrafish pathways that establish female fate, which may be conserved in other vertebrates and may more broadly provide insight into the mechanisms by which RNA-binding proteins can govern binary cell fate decisions.

Vasa, an RNA helicase of the DEAD-box helicase family also known as Ddx4, is required for germ cell differentiation and maintenance [12]. Vasa is present in the germ line from early germ cell specification throughout maturation and has sexually dimorphic transcripts that have been used as a marker for germ cells in the bi-potential gonad and to predict eventual gonad development as ovary or testis [64, 65]. Although reporters indicate higher vasa expression in females, vasa mutant gonads lack stage Ib and diplotene oocytes, and consequently form immature testis before developing exclusively as sterile males, indicating that vasa is required not only for female development, but for differentiation and fertility of both sexes [12, 65].

Another ATP-dependent RNA helicase, DEAD box helicase 5 (Ddx5), is expressed in testis in humans and is essential for spermatogenesis in mouse [66, 67]. In contrast, although expressed in both the male and female germline in zebrafish, Ddx5 is dispensable for male fertility and instead promotes differentiation and maturation of oocytes [68]. Mutants lacking ddx5 have a male sex bias and the females recovered have small ovaries with oocytes that fail to progress beyond diplotene, resembling mutants lacking both cyp19a1a and dmrt1 or lacking bmp15 [21, 51, 52, 68]. Whether Ddx5 promotes oocyte differentiation and thus maintenance of female fate through its known functions as a transcriptional coactivator or RNA helicase activity and the identity of its targets remain to be determined.

The RNA-binding protein Zar1 (zygotic arrest 1) is an evolutionarily conserved gene that is expressed in ovaries [69, 70]. In zebrafish, Zar1 is critical for oogenesis and maintenance of female fate as mutants lacking zar1 undergo early p53-mediated oocyte apoptosis and female-to-male sex-reversal. Despite apparently normal early gonad development, mutant oocyte apoptosis was observed during sexual differentiation, such that differentiating gonads contained spermatogonia and spermatocytes along with oocytes undergoing atresia [71]. Unlike the other RNA-binding protein mutants discussed above, sex-reversal of zar1 mutants has been associated with estrogen deficiency and is mediated by p53-induced apoptosis, as both oocyte loss and sex-reversal can be suppressed by mutation of p53 or by supplying mutant gonads with the synthetic estrogen agonist 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2) [71]. Thus, failure to maintain the female fate in zar1 mutants is due to oocyte loss rather than a direct role of Zar1 in sexual differentiation.

Post-translational regulation of sexual differentiation

Nedd8 (Neural precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated protein 8), a post-translational modifier of protein activity via neddylation, is important for ovarian maturation and maintenance of female secondary sex characteristics. Loss of nedd8 leads to male-biased sex ratios and hyper-masculinization of males—mutant males undergo more rapid sexual maturation, have more intense pigmentation, and were hyper-aggressive in mating and behavioral trials [72]. The females that developed in the absence of Nedd8 had deficits in oocyte maturation and fertility as exhibited by lower ovulation and fertilization rates, and strikingly exhibited breeding tubercles, a secondary sex feature characteristics of males [72]. Consistent with the masculinization of both sexes, elevated levels of 11-ketotestosterone were observed in nedd8 mutant males and females. Multiple lines of evidence support a role for Nedd8 in posttranscriptional modification and suppression of Ar activity and transcription, including elevated expression of ar and several male-determining genes in nedd8 mutants, and the presence of Nedd8 dependent modifications on endogenous Ar and in in vitro and cell culture conjugation assays [72]. Furthermore, loss of one copy of ar or treatment with an androgen antagonist partially suppresses nedd8 mutant masculinization phenotypes, placing nedd8 upstream of ar regulation [72]. The more severe fertility phenotypes of mutants lacking both nedd8 and ar indicate that Nedd8 likely regulates additional targets necessary for oocyte maturation, but these have yet to be identified.

Arginine methylation mediated by the evolutionarily conserved type II arginine methyltransferase Prmt5 (protein arginine methyltransferase 5) is essential to germ cell development and fertility across species, including zebrafish [73–75]. In zebrafish loss of prmt5 mutants leads to impaired PGC migration and reduced germ cell numbers due to germ cell loss rather than impaired proliferation because germ cell numbers decline during the period when germ cells are mitotically quiescent [75]. As expected for diminished germ cell numbers, gonadal differentiation and maturation fail resulting in infertile males. The similar phenotypes of pmrt5 mutants and those caused by loss of vasa (also known as ddx4) and ziwi, as well as biochemical data and activity assays, indicate that Prmt5 is required for arginine methylation and stabilization of essential germ cell factors, Vasa and Zili, and histone proteins [75]. The precise mechanism and pathways downstream of Prmt5 in gonad differentiation are not understood. However, because pmrt5 has additional phenotypes not present in vasa and zili mutants, it is likely that Prmt5 affects germ cell development and gonadogenesis by Vasa and Zili-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Further studies of Pmrt5 targets are expected to clarify Pmrt5’s mechanism of action.

Maintenance of sex and reversal of female fate

Zebrafish do not change their sex as part of their normal life cycle. However, mutations in certain genes cause partial or even complete reversal of adult gonadal sex from female to male, with complete reversal of primary and secondary sex characteristics while in some cases preserving fertility and in others causing sterility (Table 1). These findings powerfully signify that sex must be maintained throughout life and that specific genes are critical to maintaining female sexual identity, well after sex has initially been determined.

Maintenance of early oocytes is required to preserve female sex. Two independent studies used distinct germ cell promoters to drive the Nitroreductase system to deplete oocytes of different stages in adult zebrafish [35, 76]. While a late acting promoter, zona pellucida (zp3), led to depletion of late-stage oocytes, early oocytes were preserved and could regenerate the female germline [76]. In contrast, using an early promoter, ziwi, to express Nitroreductase depleted early oocytes and induced sex-reversal from female to male fate [35]. In cases where germ cells were completely lost, the sex-reversed males were infertile, while sex-reversed fish with partial depletion, sparing the germline stem cells, produced sperm and were fertile males [35]. Together these studies provided evidence that early oocytes are crucial for maintaining female fate and plasticity of the germline stem cells (GSCs). This suggests that stage Ib oocytes produce a factor that is sufficient to promote further ovary development, but the specific factor or factors produced by early oocytes that enable further female differentiation and prevent testis development have yet to be identified.

Nanos is an evolutionarily conserved RNA-binding protein and marker of GSCs in zebrafish, medaka, and mice [77–81], and Nanos family members are required for maintenance of GSCs in vertebrates and invertebrates [79, 82]. In mouse testis and zebrafish germ cells of both sexes, nanos2 is not required for stem cell specification but is required to maintain the GSCs [78, 79]. In zebrafish, the related nanos3 also contributes to maintenance of GSCs and is thought to act redundantly to nanos2 in females but not in males [77, 83]. Although zebrafish nanos2 is expressed in a subset of pre-meiotic GCs thought to be the GSCs, neither zygotic nanos2 nor zygotic nanos3 are essential to establish GSC fate in zebrafish [77, 78]. Instead, nanos family members in zebrafish likely prevent GSC differentiation, possibly by repressing the translation of differentiation factors, like nanos in flies [84] and mice [85, 86]. Studies of maternal nanos3 mutants showed that zebrafish germ cells are specified in the absence of Nanos3; however, the germ cell marker vasa became undetectable in mutants at 17hpf, and adult mutants lacking maternal Nanos3 were sterile [83]. Based on these observations, maternal Nanos3 is thought to regulate PGC survival. An alternative possibility that the germline is lost in maternal nanos3 mutants because cells fail to maintain PGC identity and inappropriately differentiate as somatic fates, as occurs in mutants lacking the Rbp Dead end [7], has yet to be explored. Nonetheless, nanos genes are dispensable for oocyte development and female fate per se, but indirectly cause sex-reversal due to depletion of the stem cells and the consequent failure to replenish oocytes throughout the life of the animal.

The Forkhead box family member, FOXL2, was identified as a candidate anti-testis or ovary determinant in goats carrying the Polled mutation [87]. Consistent with this function foxl2 in mice is expressed in the ovary but not the testis during early sex determination [88–90]. In humans and mice, mutation of Foxl2 causes premature ovarian failure and infertility [88–91]. Similarly, Medaka, rainbow trout, tilapia, and the zebrafish foxl2a and foxl2b genes play an important role in maintenance of female identity [63, 92–97]. Foxl2a and foxl2b are expressed in a sexually dimorphic manner in female zebrafish [63, 92]. Foxl2a and foxl2b are dispensable for early gonadal development, but have complementary functions in maintaining female sex differentiation, as foxl2a and foxl2b mutants undergo premature ovarian failure in adulthood [63]. Lack of foxl2b causes partial sex-reversal with development of testis-like areas within an intersex gonad and infertility. In contrast, loss of both genes leads to oocyte degeneration and subsequent sex-reversal with normal testicular differentiation and spermatogenesis, and to fertile males [63]. The increased expression of male-factor genes including amh, sox9a, and dmrt1 observed in single mutants, and their incomplete sex-reversal, suggest that foxl2 genes function cooperatively to suppress male-determining gene expression, as has been observed in other fish and in mammalian systems [63, 88, 90, 91, 93–95, 97].

Interactions between germline and somatic gonad and sexual fate

Evidence that at least some aspects of reproductive tract development are preserved between zebrafish and mammals comes from disruption of the canonical Wnt signaling ligand, wnt4a, which led to defects in development of the reproductive ducts in both males and females, indicating a preserved role of this gene, as it is also important in the development of the uterus and fallopian tubes in mammals [98, 99]. In addition to its role in duct formation, Wnt4a, which is likely expressed in the granulosa cells, promotes female fate, like Wnt4 does in mammals, as loss of wnt4a function results in male-biased sex ratios [98, 99]. Because some wnt4a mutants develop as females, but the majority of gonads resemble testis from the earliest stages examined, Wnt4 likely regulates female-specific differentiation rather than maintenance of female fates [99].

Bmp15 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 15), a transforming growth factor beta ligand, is a conserved ligand produced by oocytes in the early ovarian follicles of several vertebrates, including human, mouse, rat, and zebrafish. BMP15 secreted by oocytes binds to signals through BMPR2 and SMAD1 to activate target gene expression in the somatic gonad. In mouse, ovarian follicles that will develop further display higher levels of BMP15 expression than follicles that will undergo atresia [100]. In mammals, BMP15 promotes granulosa cell proliferation and inhibits the expression of Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) [101–105]. Removal of BMP15 from oocytes leads to cumulus cell/granulosa cell apoptosis in cumulus oocyte complexes—a phenotype that can be suppressed by BMP15 [106–109]. In zebrafish, Bmp15 is important in maintaining female sex, likely by promoting differentiation of somatic gonad fates and expression of cyp19a1a. Bmp15 is expressed in early-stage oocytes, and in bmp15 mutants, oocytes fail to develop past diplotene stage [21]. That bmp15 mutant follicles are surrounded by cyp19a1a-expressing theca cells but not granulosa cells, which in wild type envelop stage II oocytes, indicates that bmp15 regulates differentiation of the cyp19a1a-expressing cells that are necessary for follicle progression and maintenance of female fate. Consistent with this notion, the gonads of female mutants lacking cyp19a1a and dmrt1, like bmp15 mutant ovaries, cannot progress past diplotene [52]. In both cases, prolonged failure to progress in oogenesis, likely due to deficits in somatic gonad development and survival, results in apoptosis of female germ cells, and likely granulosa cell or other somatic fates, with consequent germline and gonad switch from female to male fate [21, 51, 52]. Notably, in males, Dmrt1 is required for differentiation of male somatic gonad fates, specifically Sertoli cells, which are required for maintenance and further differentiation of male germ cells [39]. Although Bmp15 is required to maintain oocyte fate, neither Bmp15 nor the related Gdf9 are the initial sex determination cue that promotes formation of the female follicle [21]. The identity of this elusive pre-follicle inducer remains to be determined.

Dosage-sensitive sex reversal (DAX1) is a nuclear receptor, also known as NR0B1, which antagonizes the activity of SRY. In humans, the gene encoding Dax1 resides on the X chromosome and mutations disrupting Dax1 cause X-linked congenital adrenal hypoplasia and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, whereas duplication of DAX1 leads to genetically male individuals (XY individuals) that are phenotypically female [110, 111]. Similarly, overexpression of DAX1 on a transgene in genetically male mice results in phenotypically female mice [112]. In zebrafish, nr0b1 (nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 1) is expressed in both the germline and somatic cells of the undifferentiated and mature gonads and regulates proliferation of early germ cells and somatic gonad cells [113]. As in mammals, zebrafish nr0b1 is important for female fate as nr0b1 mutants developed predominantly as fertile males, a phenotype associated with reduced numbers of germ cells found in mutant fish. Loss of nr0b1 in zebrafish also impacted somatic gonad differentiation, with increased amh expression and decreased cyp19a1a expression in somatic cells, but whether this is a secondary consequence to loss of female fate in the germ cells remains to be determined [113]. Similar to the situation in mammals, Fibroblast Growth Factor (Fgf) family members are important for development of the somatic gonad. In mice, Fgf9 is required to maintain expression of Sox9 and the male somatic gonad [114]. In zebrafish, disruption of fibroblast growth factor 24 (fgf24) leads to loss of the germline due to failed differentiation of the somatic gonad [15]. However, unlike nr0b1, loss of fgfr leads to adult sterility in the majority of mutants [15]. That nr0b1 males are fertile suggests that the gene expression differences observed in nr0b1 mutants are due to the somatic gonad cells adopting male fates rather than a differentiation defect in the somatic cells per se.

Environmental factors

Zebrafish sex is genetically determined, yet environmental factors clearly can influence sexual differentiation as well. These factors, which include suboptimal temperature, dissolved oxygen content, rearing density and food availability generally increase male ratios; thus, it is possible that a stress response induced when these factors deviate from optimal impacts the bi-potential state or the process of female differentiation through a common molecular mechanism.

Elevated rearing temperatures during critical periods of gonadal development led to male-biased sex ratios, with a dose–response relationship manifesting as higher male ratios with increasing temperatures from 33 to 37 degrees Celsius until, at a lethal temperature of 39 degrees Celsius, fish are not viable [115–117]. It is possible that elevated temperature inhibits aromatase activity, thereby leading to decreased estrogen production [116]. Alternatively, elevated temperature may alter DNA methylation patterns leading to a decreased ability to differentiate as female, as disrupted DNA methylation has been demonstrated to impact sex ratios in zebrafish [118, 119]. The feminization of fish treated with 5- azacytidine is consistent with a model wherein demethylation of the fem-rDNA loci discussed earlier promotes increased accessibility to and transcription of fem-rDNA and stabilization of female fate, but this awaits experimental verification. Another hypothesis is that environmental stressors lead to reduced germ cell numbers, thereby reducing availability of oocyte derived feminizing factors and impairing female differentiation [5]. These temperature-related findings provide important information regarding the potential long-term impact of global warming on zebrafish populations [117, 120].

Oxygen content in water also influences sex ratios. Specifically, hypoxic conditions of dissolved O2 compared to normal conditions leads to elevated proportions of males, and has been associated with downregulation of genes involved in sex hormone synthesis including cyp19a [121]. The observation that hypoxia led to impaired migration of the PGCs suggests that deficiency of germ cells at the gonad anlage may explain the male-biased sexual differentiation [122].

Rearing density impacts not only overall well-being, but also sex ratios of zebrafish. Rearing fish at optimal densities, for example, up to 40–50 fish per tank depending on the volume of the tank, does not affect sex ratios, while doubling the density leads to an increased proportion of males [30, 123]. This is likely due, at least in part, to limited food availability and increased waste resulting from overcrowded conditions. Consistent with this notion, decreased food availability resulted in male-biased ratios, while doubling food quantity increased the proportion of females observed [124]. Likewise, treatment with cortisol had a similar effect, leading to complete masculinization; thus, it is possible that the impacts of rearing density and food availability are mediated by a stress-induced rise in cortisol [125].

Several endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) including persistent bioaccumulative halogenated chemicals, less bioaccumulative chemicals, such as bisphenol A and bisphenol S, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, phytoestrogens, and natural hormones, have been studied with regard to their impact on zebrafish sexual differentiation [120]. For example, exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations 17β-trenbolone, a metabolite which is found in waters proximal to animals fed with the androgenic growth promoter trenbolone, was associated with irreversible masculinization of zebrafish [126]. Continuous exposure to Bisphenol A, a pervasive chemical found in many plastics, was associated with decreased sperm density and quality and female-biased sex ratios [127]. These effects were even more pronounced in offspring, with hatching and malformation defects found in F2 but not F1 females [127]. Fish exposed to the phytosterol β-sitosterol, which may be metabolized into both estrogenic and androgen compounds, was associated with male-biased sex ratios in F1 and female-biased sex ratios in F2 [128]. These findings highlight the potentially compounded generational effects of EDC exposure. Impacts of additional chemicals on gonadal maturation, fertility, and both male- and female-biased sex ratios have been observed and while a detailed summary is beyond the scope of this review, these effects have been extensively reviewed in Santos et al. [120]. These studies provide valuable insight into the potential effects of EDCs on vertebrate sexual development and can provide guidance as to which should be targeted by environmental regulation policies.

Uncovering the enigmatic spark that sets off zebrafish sexual differentiation

Thus far we have reviewed a variety of genetic pathways involved in zebrafish sexual differentiation and development. However, the initial cue that determines male versus female fate in zebrafish has yet to be discovered. Upstream regulators of the maternal-specific 45S ribosomal fem-rDNA that is encoded for on the sex-associated loci reported on zebrafish chromosome 4 and amplified in the oocyte stage required for female fate, are compelling candidate triggers in determining sexual fate in zebrafish. These upstream factors include the methyltransferases, demethylases and their associated cofactors that are responsible for transcriptional silencing and activation, as well as post-transcriptional gene regulation. Further, the methyltransferases themselves are subject to post-translational modifications, including methylation and phosphorylation, which can impact the activity or stability of these enzymes (reviewed in [129]). For example, in cultured mammalian cells, DNMT1 can be stabilized by AKT1-mediated phosphorylation [130, 131], an observation that is compelling because it links regulation, at least of this methyltransferase, to the nutrient sensing and cell cycle regulating PI3K-AKT-mTor pathway, which might account for the widely known, but not understood, relationship between nutritional status and sexual fate in zebrafish.

The observation that indeterminate gonads express both genes required for male and female differentiation makes RNA regulation and RNA-binding proteins in particular, owing to their known roles in regulating RNA metabolism including RNA translational status and stability, compelling candidates as gatekeepers of sex determination in zebrafish. The presence of both factors in bulk sequence data indicates that either the gonad is composed of cells with potential to become male or female or that the cells are poised to take either a female fate or a male fate. In the latter model, the female RNAs would be translated and the male RNAs translationally repressed since the early gonad more closely resembles an ovary (Fig. 3). In this scenario, commitment to oocyte and female fate could reinforce expression of female promoting genes and repression of male promoting genes to allow for further ovary differentiation, while derepression of male factors, possibly due to diminished expression of a repressive female promoting factor, would lead to antagonism and elimination of the female promoting transcripts and reinforce male-factor translation and gene expression (Fig. 3). Indeed, in mammalian cells, RNAs themselves have been implicated in global regulation of gene expression by interaction with DNMT1 to block DNA methylation in a gene-specific manner [132]. Whether a similar mechanism acts in the germline remains to be determined. In the case of sex determination, one could envision non-mutually exclusive models wherein RNA-binding proteins could act upstream of methyltransferases to regulate fem-rDNA levels or could promote the stability or turnover of an RNA that could modulate DNA methylation in a locus-specific manner (Fig. 3). Indeed, in zebrafish, Rbpms2 is essential for female fates even in the absence of Dmrt1 [52]; therefore, it is likely that learning how Rbpms2 is regulated and identifying its targets and mechanism of action in sex determination will be an important step toward identifying the elusive cue or switch regulator governing sexual fate in zebrafish. Whether a single factor or multifactorial mechanism sparks sexual differentiation in domesticated zebrafish, it is clear that the female sexual fate retains plasticity and can be altered in response to environmental or genetic contexts. Ultimately, further research will elucidate the underlying deciding factor in sexual determination of this widely used model organism.

Fig. 3.

Models for potential candidates and mechanisms to spark sex determination in zebrafish. The bi-potential gonad (purple) contains RNAs that are required for either female (pink) or male (blue) differentiation. Because the bi-potential gonad is more female in character, resembling an early ovary, it is likely that the RNAs encoding male factors are translationally repressed, while those required for female differentiation are translated. Rbpms2 is a candidate regulator because it is essentially for female fates even in the absence of Dmrt1—it could act to translationally repress male RNAs while simultaneously promoting translation of factors required for female fate, either directly or with a corepressor of co-activating RNAbp. Because fem-rDNA amplification is required for female fate, methyltransferases and their regulators are compelling triggers for female differentiation. Likewise, their loss could trigger male differentiation. How fem-rDNA contributes to sexual differentiation is not known; however, given the presence of both female and male RNAs in the bi-potential gonad, it is tempting to speculate that the state of fem-rDNA (high in females and low in males) dictates which RNAs are translated. Genetic evidence indicates that loss of Rbpms2 is sufficient for male development, and that Dmrt1 antagonizes Rbpms2. If Rbpms2 represses male RNAs then eliminating Rbpms2 so that another male-specific RNAbp could bind and promote male-factor RNA translation would be sufficient to trigger female fates. These models and the cue that initiates sex determination in zebrafish await experimental verification

Discussion and perspective

The process of sexual differentiation among zebrafish is highly complex and involves multiple intersecting pathways that have only just begun to be understood. A number of genes have been identified whose absence results in failed sexual maturation or a switch in sex, which clearly play major roles in sexual differentiation (Table 1). However, an underlying determinant that governs the initial decision to develop as male or female has yet to be established. As discussed, RNA-binding proteins are among the intriguing candidate regulators, as they possess activities with the potential to suppress or trigger a variety of downstream processes that are essential for sexual differentiation. Further understanding of the regulators and targets of known and identification of additional sex-determining genes may reveal conserved pathways in vertebrate sexual development and may provide targets for therapeutics to address disorders of sexual differentiation, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, premature ovarian failure, and reproductive cancers.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the NIH for supporting our research, to CCMS for animal care and husbandry, and to our colleagues for thoughtful discussions.

Author contributions

DA and FLM wrote this review article and generated all figures.

Funding

Research on sex determination in the Marlow lab is supported by NIHR01 GM133896 to FLM.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All researches in the Marlow lab are reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and veterinary and husbandry are overseen by the Center for Comparative Medicine.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publication of this review article.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gempe T, Beye M. Function and evolution of sex determination mechanisms, genes and pathways in insects. BioEssays. 2011;33(1):52–60. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachtrog D, et al. Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS Biol. 2014;12(7):e1001899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trukhina AV, et al. The variety of vertebrate mechanisms of sex determination. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:587460. doi: 10.1155/2013/587460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herpin A, Schartl M. Plasticity of gene-regulatory networks controlling sex determination: of masters, slaves, usual suspects, newcomers, and usurpators. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(10):1260–1274. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kossack ME, Draper BW. Genetic regulation of sex determination and maintenance in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Curr Top Dev Biol. 2019;134:119–149. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon C, Kawakami K, Hopkins N. Zebrafish vasa homologue RNA is localized to the cleavage planes of 2- and 4-cell-stage embryos and is expressed in the primordial germ cells. Development. 1997;124(16):3157–3165. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross-Thebing T, et al. The vertebrate protein dead end maintains primordial germ cell fate by inhibiting somatic differentiation. Dev Cell. 2017;43(6):704–715.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegfried KR, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Germ line control of female sex determination in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;324(2):277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidinger G, et al. dead end, a novel vertebrate germ plasm component, is required for zebrafish primordial germ cell migration and survival. Curr Biol. 2003;13(16):1429–1434. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Orazio FM, et al. Germ cell differentiation requires Tdrd7-dependent chromatin and transcriptome reprogramming marked by germ plasm relocalization. Dev Cell. 2021;56(5):641–656.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redl S, et al. Extensive nuclear gyration and pervasive non-genic transcription during primordial germ cell development in zebrafish. Development. 2021;148:2. doi: 10.1242/dev.193060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartung O, Forbes MM, Marlow FL. Zebrafish vasa is required for germ-cell differentiation and maintenance. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81(10):946–961. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Köprunner M, et al. A zebrafish nanos-related gene is essential for the development of primordial germ cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15(21):2877–2885. doi: 10.1101/gad.212401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braat AK, et al. Characterization of zebrafish primordial germ cells: morphology and early distribution of vasa RNA. Dev Dyn. 1999;216(2):153–167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199910)216:2<153::AID-DVDY6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leerberg DM, Sano K, Draper BW. Fibroblast growth factor signaling is required for early somatic gonad development in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(9):e1006993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertho S, et al. Zebrafish dazl regulates cystogenesis and germline stem cell specification during the primordial germ cell to germline stem cell transition. Development. 2021;148:7. doi: 10.1242/dev.187773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez-Marí A, et al. Characterization and expression pattern of zebrafish anti-Müllerian hormone (Amh) relative to sox9a, sox9b, and cyp19a1a, during gonad development. Gene Exp Patterns. 2005;5(5):655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi H. Juvenile hermaphroditism in the zebrafish, Brachydanio rerio. Bull Fac Fish Hokkaido Univ. 1977;28:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tzung KW, et al. Early depletion of primordial germ cells in zebrafish promotes testis formation. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez-Marí A, et al. Sex reversal in zebrafish fancl mutants is caused by Tp53-mediated germ cell apoptosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(7):e1001034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dranow DB, et al. Bmp15 is an oocyte-produced signal required for maintenance of the adult female sexual phenotype in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(9):e1006323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiller C, Wilhelm D, Koopman P. Cell cycle analysis of fetal germ cells during sex differentiation in mice. Biol Cell. 2009;101(10):587–598. doi: 10.1042/BC20090021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster KA, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 21 is a novel regulator of proliferation and meiosis in the male germline of zebrafish. Reproduction. 2018;157(4):383–398. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Mari A, Postlethwait JH. The role of Fanconi anemia/BRCA genes in zebrafish sex determination. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;105:461–490. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shive HR, et al. brca2 in zebrafish ovarian development, spermatogenesis, and tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(45):19350–19355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011630107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson CA, et al. Wild sex in zebrafish: loss of the natural sex determinant in domesticated strains. Genetics. 2014;198(3):1291–1308. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.169284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JL, et al. Multiple sex-associated regions and a putative sex chromosome in zebrafish revealed by RAD mapping and population genomics. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley KM, et al. An SNP-based linkage map for zebrafish reveals sex determination loci. G3 (Bethesda) 2011;1(1):3–9. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howe K, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013;496(7446):498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liew WC, et al. Polygenic sex determination system in zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e34397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HJ, Hore TA, Reik W. Reprogramming the methylome: erasing memory and creating diversity. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(6):710–719. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortega-Recalde O, et al. Zebrafish preserve global germline DNA methylation while sex-linked rDNA is amplified and demethylated during feminisation. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3053. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10894-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skvortsova K, et al. Retention of paternal DNA methylome in the developing zebrafish germline. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3054. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchida D, et al. Oocyte apoptosis during the transition from ovary-like tissue to testes during sex differentiation of juvenile zebrafish. J Exp Biol. 2002;205(Pt 6):711–718. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dranow DB, Tucker RP, Draper BW. Germ cells are required to maintain a stable sexual phenotype in adult zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2013;376(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gagnon JA, et al. Efficient mutagenesis by Cas9 protein-mediated oligonucleotide insertion and large-scale assessment of single-guide RNAs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matson CK, Zarkower D. Sex and the singular DM domain: insights into sexual regulation, evolution and plasticity. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(3):163–174. doi: 10.1038/nrg3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webster KA, et al. Dmrt1 is necessary for male sexual development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2017;422(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin Q, et al. Distinct and cooperative roles of amh and dmrt1 in self-renewal and differentiation of male germ cells in zebrafish. Genetics. 2017;207(3):1007–1022. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan YL, et al. A hormone that lost its receptor: anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) in zebrafish gonad development and sex determination. Genetics. 2019;213(2):529–553. doi: 10.1534/genetics.119.302365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z, et al. Genetic evidence for Amh modulation of gonadotropin actions to control gonadal homeostasis and gametogenesis in zebrafish and its noncanonical signaling through Bmpr2a receptor. Development. 2020;147:22. doi: 10.1242/dev.189811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan YL, et al. Gonadal soma controls ovarian follicle proliferation through Gsdf in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2017;246(11):925–945. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersson O, et al. Synergistic interaction between Gdf1 and nodal during anterior axis development. Dev Biol. 2006;293(2):370–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka C, et al. Long-range action of nodal requires interaction with GDF1. Genes Dev. 2007;21(24):3272–3282. doi: 10.1101/gad.1623907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marlow FL. Setting up for gastrulation in zebrafish. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2020;136:33–83. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Little SC, Mullins MC. Bone morphogenetic protein heterodimers assemble heteromeric type I receptor complexes to pattern the dorsoventral axis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(5):637–643. doi: 10.1038/ncb1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu G, et al. Zebrafish androgen receptor is required for spermatogenesis and maintenance of ovarian function. Oncotarget. 2018;9(36):24320–24334. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crowder CM, Lassiter CS, Gorelick DA. Nuclear androgen receptor regulates testes organization and oocyte maturation in zebrafish. Endocrinology. 2018;159(2):980–993. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau ES, et al. Knockout of zebrafish ovarian aromatase gene (cyp19a1a) by TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 leads to all-male offspring due to failed ovarian differentiation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37357. doi: 10.1038/srep37357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin Y, et al. Targeted disruption of aromatase reveals dual functions of cyp19a1a during sex differentiation in zebrafish. Endocrinology. 2017;158(9):3030–3041. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu K, et al. Disruption of dmrt1 rescues the all-male phenotype of the cyp19a1a mutant in zebrafish - a novel insight into the roles of aromatase/estrogens in gonadal differentiation and early folliculogenesis. Development. 2020;147:4. doi: 10.1242/dev.182758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romano S, Kaufman OH, Marlow FL. Loss of dmrt1 restores zebrafish female fates in the absence of cyp19a1a but not rbpms2a/b. Development. 2020;147:18. doi: 10.1242/dev.190942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quirk JG, Hamilton JB. Number of germ cells in known male and known female genotypes of vertebrate embryos (Oryzias latipes) Science. 1973;180(4089):963–964. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4089.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishimura T, et al. Germ cells in the teleost fish medaka have an inherent feminizing effect. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(3):e1007259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakamura S, et al. Hyperproliferation of mitotically active germ cells due to defective anti-Müllerian hormone signaling mediates sex reversal in medaka. Development. 2012;139(13):2283–2287. doi: 10.1242/dev.076307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morinaga C, et al. The hotei mutation of medaka in the anti-Mullerian hormone receptor causes the dysregulation of germ cell and sexual development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(23):9691–9696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611379104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis ZR, et al. Female-specific increase in primordial germ cells marks sex differentiation in threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) J Morphol. 2008;269(8):909–921. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurokawa H, et al. Germ cells are essential for sexual dimorphism in the medaka gonad. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):16958–16963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609932104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hartung OMF (2014) Get it together: how RNA-binding proteins assemble and regulate germ plasm in the oocyte and embryo. In: (Lessman CE ed) Zebrafish: topics in reproduction, toxicology and development. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, pp 65–106

- 60.Kaufman OH, et al. rbpms2 functions in Balbiani body architecture and ovary fate. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(7):e1007489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farazi TA, et al. Identification of the RNA recognition element of the RBPMS family of RNA-binding proteins and their transcriptome-wide mRNA targets. RNA. 2014;20(7):1090–1102. doi: 10.1261/rna.045005.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zearfoss NR, et al. Hermes is a localized factor regulating cleavage of vegetal blastomeres in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2004;267(1):60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang YJ, et al. Sequential, divergent, and cooperative requirements of Foxl2a and Foxl2b in ovary development and maintenance of zebrafish. Genetics. 2017;205(4):1551–1572. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.199133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Braat AK, et al. Vasa protein expression and localization in the zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2000;95(1–2):271–274. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krøvel AV, Olsen LC. Sexual dimorphic expression pattern of a splice variant of zebrafish vasa during gonadal development. Dev Biol. 2004;271(1):190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neuhaus N, et al. Single-cell gene expression analysis reveals diversity among human spermatogonia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2017;23(2):79–90. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Legrand JMD, et al. DDX5 plays essential transcriptional and post-transcriptional roles in the maintenance and function of spermatogonia. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2278. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09972-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sone R, et al. Critical roles of the ddx5 gene in zebrafish sex differentiation and oocyte maturation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14157. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu X, et al. Zygote arrest 1 (Zar1) is a novel maternal-effect gene critical for the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Nat Genet. 2003;33(2):187–191. doi: 10.1038/ng1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uzbekova S, et al. Zygote arrest 1 gene in pig, cattle and human: evidence of different transcript variants in male and female germ cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miao L, et al. Translation repression by maternal RNA binding protein Zar1 is essential for early oogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 2017;144(1):128–138. doi: 10.1242/dev.144642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu G, et al. Zebrafish Nedd8 facilitates ovarian development and the maintenance of female secondary sexual characteristics via suppression of androgen receptor activity. Development. 2020;147:18. doi: 10.1242/dev.194886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim S, et al. PRMT5 protects genomic integrity during global DNA demethylation in primordial germ cells and preimplantation embryos. Mol Cell. 2014;56(4):564–579. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Y, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (Prmt5) is required for germ cell survival during mouse embryonic development. Biol Reprod. 2015;92(4):104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.127308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu J, et al. Zebrafish prmt5 arginine methyltransferase is essential for germ cell development. Development. 2019;146:20. doi: 10.1242/dev.179572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.White YA, Woods DC, Wood AW. A transgenic zebrafish model of targeted oocyte ablation and de novo oogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2011;240(8):1929–1937. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beer RL, Draper BW. nanos3 maintains germline stem cells and expression of the conserved germline stem cell gene nanos2 in the zebrafish ovary. Dev Biol. 2013;374(2):308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cao Z, Mao X, Luo L. Germline Stem Cells Drive Ovary Regeneration in Zebrafish. Cell Rep. 2019;26(7):1709–1717e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sada A, et al. The RNA-binding protein NANOS2 is required to maintain murine spermatogonial stem cells. Science. 2009;325(5946):1394–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.1172645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aoki Y, et al. Expression and syntenic analyses of four nanos genes in medaka. Zool Sci. 2009;26(2):112–118. doi: 10.2108/zsj.26.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakamura S, et al. Identification of germline stem cells in the ovary of the teleost medaka. Science. 2010;328(5985):1561–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1185473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Forbes A, Lehmann R. Nanos and Pumilio have critical roles in the development and function of Drosophila germline stem cells. Development. 1998;125(4):679–690. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Draper BW, McCallum CM, Moens CB. nanos1 is required to maintain oocyte production in adult zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2007;305(2):589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Z, Lin H. Nanos maintains germline stem cell self-renewal by preventing differentiation. Science. 2004;303(5666):2016–2019. doi: 10.1126/science.1093983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Suzuki H, et al. The Nanos3–3'UTR is required for germ cell specific NANOS3 expression in mouse embryos. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e9300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barrios F, et al. Opposing effects of retinoic acid and FGF9 on Nanos2 expression and meiotic entry of mouse germ cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 6):871–880. doi: 10.1242/jcs.057968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boulanger L, et al. FOXL2 is a female sex-determining gene in the goat. Curr Biol. 2014;24(4):404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ottolenghi C, et al. Foxl2 is required for commitment to ovary differentiation. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(14):2053–2062. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Uhlenhaut NH, et al. Somatic sex reprogramming of adult ovaries to testes by FOXL2 ablation. Cell. 2009;139(6):1130–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmidt D, et al. The murine winged-helix transcription factor Foxl2 is required for granulosa cell differentiation and ovary maintenance. Development. 2004;131(4):933–942. doi: 10.1242/dev.00969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Crisponi L, et al. The putative forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is mutated in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27(2):159–166. doi: 10.1038/84781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Caulier M, et al. Localization of steroidogenic enzymes and Foxl2a in the gonads of mature zebrafish (Danio rerio) Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2015;188:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bertho S, et al. Foxl2 and its relatives are evolutionary conserved players in gonadal sex differentiation. Sex Dev. 2016;10(3):111–129. doi: 10.1159/000447611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bertho S, et al. The unusual rainbow trout sex determination gene hijacked the canonical vertebrate gonadal differentiation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(50):12781–12786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803826115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang DS, et al. Foxl2 up-regulates aromatase gene transcription in a female-specific manner by binding to the promoter as well as interacting with ad4 binding protein/steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(3):712–725. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kobayashi T, et al. Estrogen alters gonadal soma-derived factor (Gsdf)/Foxl2 expression levels in the testes associated with testis-ova differentiation in adult medaka, Oryzias latipes. Aquat Toxicol. 2017;191:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang X, et al. Mutation of foxl2 or cyp19a1a results in female to male sex reversal in XX Nile tilapia. Endocrinology. 2017;158(8):2634–2647. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sreenivasan R, et al. Gonad differentiation in zebrafish is regulated by the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Biol Reprod. 2014;90(2):45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.110874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kossack ME, et al. Female sex development and reproductive duct formation depend on Wnt4a in zebrafish. Genetics. 2019;211(1):219–233. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Su YQ, et al. Synergistic roles of BMP15 and GDF9 in the development and function of the oocyte-cumulus cell complex in mice: genetic evidence for an oocyte-granulosa cell regulatory loop. Dev Biol. 2004;276(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aaltonen J, et al. Human growth differentiation factor 9 (GDF-9) and its novel homolog GDF-9B are expressed in oocytes during early folliculogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(8):2744–2750. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shimasaki S, et al. The bone morphogenetic protein system in mammalian reproduction. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(1):72–101. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moore RK, Erickson GF, Shimasaki S. Are BMP-15 and GDF-9 primary determinants of ovulation quota in mammals? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(8):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]