Abstract

Background

Talus is a critical component of the ankle joint that allows multidirectional movement essential for gait and mobility. Talus prostheses are typically used in cases of severe trauma, avascular necrosis, or end-stage arthritis. Adjacent joint arthritis is the most common complication after total talar replacement (TTR). While intervention is rarely required, varying degrees of postoperative degenerative changes have been reported in surrounding joints. Therefore, a detail evaluation of /the mechanical stability and stress distribution within talus prostheses is crucial. Recent advancements, including patient-specific implants and improved biomaterials, show promise in enhancing long-term outcomes and reducing complication rates.

Aim

This study investigates the mechanical stability and stress distribution changes in a talus prosthesis after the sequential removal of surrounding ligaments and the application of varying thicknesses of cartilage overlays.

Methods

Finite element analysis (FEA) was employed using CT data to create a 3D model of the talus prosthesis. The model was refined using Mimics, Geomagic, and SolidWorks, and then analyzed with Ansys. The mechanical properties of bone, prosthesis, skin, ligament, and cartilage were incorporated into the model. Various ankle positions, including neutral, dorsiflexion (5° and 10°), and plantarflexion (5°, 10°, 15°, 20°and 30°), were simulated under different ligament removal conditions.

Results

The sequential removal of surrounding ligaments, including lateral, medial, sinus tarsi, and talonavicular ligaments, did not significantly affect the stability of the talus prosthesis. Stress values ranged from 2.2257 to 3.0218 MPa, and displacement values were stable around 1.6611 to 2.2119 mm across different conditions. By comparing the effects of different cartilage thicknesses on contact area and contact stress across various flexion angles, we have the optimized the cartilage thickness, and identified a 0.5mm cartilage overlay resulted in stress distributions most similar to a normal ankle joint, enhancing the prosthesis performance.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that the removal of surrounding ligaments does not compromise the stability of the talus prosthesis. Importantly, a 0.5 mm cartilage overlay is optimal for achieving stress distributions comparable to a normal ankle joint. These findings offer valuable preliminary insights into stress distribution patterns following talus prosthesis implantation; however, they represent an initial step, and further experimental and clinical studies are needed to validate and extend these results.

Level of evidence

Level V, computational simulation study.

Keywords: Talus prosthesis, Finite element analysis, Ligament removal, Cartilage overlay, Biomechanical stability, Stress distribution, Ankle joint, Prosthesis design

Introduction

Talus prostheses are typically used in cases of severe talus injury, avascular necrosis, or other conditions that lead to the deterioration of the talus bone [1], which is a critical component of the ankle joint [2], and allows for a range of movements necessary for walking, running, and other activities [3]. Unlike joint fusion, which can significantly limit the range of motion, a talus prosthesis aims to preserve the natural movement of the ankle joint, thereby improving the patient's quality of life. The prosthesis also provides a structural substitute that helps in maintaining the anatomical alignment and function of the foot and ankle, which is crucial for overall balance and gait [2, 4].

Total talar replacement (TTR) has emerged as a promising solution for patients with advanced talus pathology, such as avascular necrosis or complex trauma. It aims to preserve joint motion and avoid arthrodesis [5]. However, despite improved functional outcomes compared to fusion, long-term follow-up studies have identified complications, particularly adjacent joint degeneration. In an 8-year study by Taniguchi et al., showed degenerative changes in the tibial-talar joint in 24 cases, subtalar joint in 19 cases, and talonavicular joint in 5 cases out of 55 implanted feet [6]. Earlier reports also found sclerosis in the tibia or calcaneus in over half of the cases, revealing the concern over secondary joint deterioration following TTR [7]. A major contributing factor to adjacent joint degeneration is abnormal stress distribution, especially at the interface between the prosthesis and the tibial cartilage [8]. This may be caused by the lack of surrounding ligament structures or suboptimal cartilage conformity in prosthetic design. Previous FEA study in hemiarthroplasty has shown that larger clearances between implant and native cartilage lead to increased peak contact stresses, reduced contact areas, and accelerated cartilage consolidation, particularly at the center of the joint surface. This effect is most pronounced at the center of the opposing cartilage surface, suggesting that clearance and fit are critical in controlling stress concentration and long-term wear [9].

In addition, cadaveric biomechanical studies have consistently shown that transection of specific ligaments around the talus, such as the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and medial collateral ligament (MCL), can cause measurable instability in the talus under various sagittal and frontal plane positions [10–15]. This indicates that prosthesis stabilization must account for ligament absence or insufficiency, particularly under dorsiflexion and plantarflexion movements where instability is more pronounced.

While numerous studies have applied FEA to orthopedic implants, such as hip and knee replacements, as well as to fracture fixation devices [16–20], none have specifically addressed its application to the unique biomechanics of the talus and the challenges associated with its prosthetic replacement. In this study, we aim to use a finite element model of the ankle joint to evaluate the mechanical stability of a talus prosthesis under dorsiflexion and plantarflexion after ligament removal, and the effects of different cartilage thickness configurations on stress distribution in the tibial cartilage. By identifying configurations that minimize stress concentration, the findings can help guide future prosthesis design criteria, reduce the risk of adjacent joint degeneration, and improve the long-term outcomes of TTR.

Methods

Data source

CT imaging was performed using a GE Discovery CT750 HD scanner. The patient, a healthy 25-year-old male (170 cm, 60 kg), was positioned supine with feet first during the scan. Parameters were as follows: tube current 350 mAs, tube voltage 120 kV, volume scan thickness 5 mm, reconstruction slice thickness 1.25 mm, and interval 1.0 mm. Soft tissue window settings were 350/50, and bone window settings were 2400/1000. The field of view (FOV) was 40 cm × 40 cm with a matrix of 512 × 512. Scanning time was 3 s. Original CT data were imported into the workstation for volume rendering (VR) and multiplanar reconstruction (MPR). The 3D CT data was confirmed to be usable and sufficiently clear before use. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Model development and segmentation

All CT images (in DICOM format) of a healty subject's ankle joint were imported to Mimics software (version 21, Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Segmentation of cortical and cancellous bone structures was achieved by setting specific Hounsfield Unit (HU) thresholds. Trabecular (cancellous) bone was generated using the"Offset"function in Geomagic software (version 21, 3D Systems, USA) after cortical extraction. Soft tissue structures were segmented separately. Skin was extracted in Mimics software using a"New Mask"with specific HU range thresholds for soft tissues. Ligaments were reconstructed manually in SolidWorks 2021 (Dassault Systèmes, France) using"Sketch"and"Lofted Boss"commands. The shapes and anatomical insertion points of the ligaments were drawn based on 3D anatomical references obtained from 3Dbody datasets.

Noise and unconnected artifacts were manually removed, and bone structures were separated. The initial surface of each segmented model was optimized using commands such as"Relax,""Remove Spikes,"and"Remove Noise", to improve mesh quality. The general procedure is illustrated in the Fig. 1A. The resulting 3D models were exported in STL format for further processing (Fig. 1B–D).

Fig. 1.

Displacement and contact stress analysis of talus prosthesis with cartilage. A Workflow for FEA. B Surface fitting using Geomagic. C Loading settings for FEA. Fixed support constraints are applied to the upper ends of the tibia and fibula. A force of 500 N is applied to the plantar surface (bottom) of the foot model. D 3D reconstruction of the foot model at the stages of bone structure model, ligament and achilles tendon model, and skin and soft tissue model. E Finite element mesh models of the foot at different refinement stages used for simulation in ANSYS

Foot positioning for dorsiflexion and plantarflexion

To simulate dorsiflexion and plantarflexion angles, a rotation axis was defined between the lateral malleolus tip and the medial malleolus inferior edge, approximating the true ankle joint axis. The dorsiflexion and plantarflexion angles were simulated by rotating the foot model around the anatomical axis, followed by static loading at each positioned angle (Fig. 1E). Foot models were rotated around this axis to achieve desired dorsiflexion and plantarflexion angles. All biological tissues, including bones, skin, and ligaments, were rotated together to maintain anatomical integrity during movement simulation. The stability of the talus prosthesis at different flexion positions was evaluated by measuring displacement values in the X, Y, and Z directions.

Finite element model preparation

All models were exported in STEP format and imported into SolidWorks for final assembly. The full ankle-foot model, including bones, ligaments, cartilage, and skin, was exported in X_T format into Ansys Workbench (version 17.0, ANSYS Inc., USA). Material properties for each structure were assigned based on previous literature (summarized in Table 1). Cortical bone, trabecular bone, cartilage, skin, and ligaments were modeled as homogeneous and isotropic materials. Boundary conditions were applied by fixing the superior surfaces of the tibia and fibula [21]. A 500 N vertical load was applied at the plantar surface to simulate static standing conditions [22]. This load was selected to replicate the typical weight-bearing forces during standing. However, it is important to note that both the magnitude and distribution of the applied force would differ under dynamic conditions, especially when the bipedal stance is not maintained. Additionally, the distribution of the weight-bearing force varies significantly between plantarflexion and dorsiflexion, leading to changes in the stress distribution across the joint surfaces. As a result, the 500 N load serves as a baseline representative of standing conditions. Different cartilage overlay thicknesses (0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 mm) were studied based on reported talar cartilage thickness ranges in the literature, which vary from 0.48 to 2.0 mm [23–25].

Table 1.

Element type and material properties of the FE model

| Components | Mechanical properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | E = 125 MPa, v = 0.4 | Gefen A, Megido-Ravid M, Itzchak Y, Arcan M. Analysis of muscular fatigue and foot stability during high-heeled gait. Gait Posture. 2002 Feb;15(1):56–63. |

| Ligments& Muscles | E = 260 MPa, v = 0.4 | Chen TL, Wang Y, Peng Y, Zhang G, Hong TT, Zhang M. Dynamic finite element analyses to compare the influences of customised total talar replacement and total ankle arthroplasty on foot biomechanics during gait. J OrthopTranslat. 2022 Oct 18;38:32–43. |

| Cartilage | E = 1 MPa, v = 0.4 | Taghizadeh Y, Chitsazan A, Pezeshki S, Taghizadeh H, Rouhi G. Total ankle replacement along with subtalar joint arthrodesis: In-vitro and in-silico biomechanical investigations. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2021 Sep;37(9):e3514. |

| Cortical and trabecular | E = 7300 MPa, v = 0.3 | Li J, Wang Y, Wei Y, Kong D, Lin Y, Wang D, Cheng S, Yin P, Wei M. The effect of talus osteochondral defects of different area size on ankle joint stability: a finite element analysis. BMC MusculoskeletDisord. 2022 May 27;23(1):500. |

| Talar prosthesis | E = 210,000 MPa, v = 0.29 | Liu T, Jomha N, Adeeb S, El-Rich M, Westover L. The evaluation of artificial talus implant on ankle joint contact characteristics: a finite element study based on four subjects. Med Biol EngComput. 2022 Apr;60(4):1139–1158. |

Only sagittal plane motion (dorsiflexion to plantarflexion) was simulated in this study, as TTR removes the surrounding ligaments that normally control rotational and inversion–eversion movements [2]. Without these constraints, complex three-dimensional gait kinematics cannot be reliably predicted. Moreover, clinical observations show that ankle motion after total talar replacement predominantly occurs in the sagittal plane, making this simplification both clinically relevant and mechanically representative.

Mesh generation and convergence test

Tetrahedral elements were used for meshing. The initial model used the automatic meshing function, producing 323,677 nodes and 177,053 elements. A mesh convergence test was performed by discretizing the geometry with following element sizes. (1) Mesh 1: System automatic meshing; 323,677 nodes, 177,053 elements; maximum von Mises stress = 11.45 MPa. (2) Mesh 2: Element size 5 mm; 350,818 nodes, 193,269 elements; maximum von Mises stress = 5.6145 MPa. (3) Mesh 3: Element size 4.5 mm; 400,772 nodes, 223,819 elements; maximum von Mises stress = 4.8687 MPa. (4) Mesh 4: Element size 4 mm; 441,172 nodes, 244,192 elements; maximum von Mises stress = 5.2601 MPa.

Mesh convergence was assessed by comparing maximum von Mises stress values. When the predicted stress difference between two successive mesh refinements was less than 10%, the mesh was considered converged. Between 4.5 and 4 mm element sizes, the stress values differed by 7.44%, meeting the convergence criterion. Therefore, the 4.5 mm mesh was selected for further analysis, balancing computational efficiency and result accuracy.

Choosing a finer mesh (4.0 mm) would slightly improve accuracy but significantly increase computational time and resources with only marginal benefit (stress difference <10%). Conversely, coarser meshes (5 mm or automatic) resulted in noticeable stress prediction discrepancies and were therefore not adopted.

Model validation

For model validation, we compared the contact pattern, contact area, peak contact pressure, and mean contact pressure of our models with Anderson’s experiments [26] (Table 2). Agreement between the model predictions and experimental values supported the validity of the modeling approach.

Table2.

Comparison of results between FEModel validation and the expremental work of Anderson et al. (2017)

| Items | Max contact stress (MPa) | Contact area (mm2) |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 2.7–4.0 | 453–527 |

| FE model | 2.7681 | 496.39 |

Result

Impact of sequential ligament removal on the stress and displacement of the talus prosthesis

In talus replacement surgery, it is necessary to remove ligaments connected to the talus (including the lateral, medial, sinus tarsi, and talonavicular ligaments) [27]. We utilized a finite element analysis to determine which ligament most significantly impacts the stability of the talus through removing the ligament one by one, thereby assessing whether ligament reconstruction is necessary during talus prosthesis replacement. This assessment is crucial as some clinical cases reported the reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament or the talonavicular ligament, or even direct subtalar joint fusion.

The sequential ligament removal model of the patient was tested on the original talus prosthesis model. When the stability of the talus was measured by stress and displacement, the removal of surrounding ligaments did not significantly affect the stability of the talus prosthesis during various ankle positions, including neutral, dorsiflexion (5° and 10°), and plantarflexion (5°, 10°, 20°, and 30°) (Table 3). Briefly, the stress values remained relatively consistent, ranging from approximately 2.2257–3.0218 MPa, while displacement values were stable around 1.6611 to 2.2119 mm (Table3). Moreover, both stress and displacement have shown minor variations after the removal of lateral, medial, sinus tarsi, and talonavicular ligaments, suggesting that the talus prosthesis relies on its inherent bony anatomy to maintain stability during flexion and extension movements. This finding implies that ligament reconstruction may not be necessary for maintaining the prosthesis's mechanical integrity and stability in clinical scenarios.

Table 3.

Effects of ligament removal on talus prosthesis stress and displacement

| ligament removal condition | Neutral | Dorsiflexion 5° | Dorsiflexion 10° | Plantarflexion 5° | Plantarflexion 10° | Plantarflexion 20° | Plantarflexion 30° | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | STR (MPa) | DIS (mm) | ||

| No | 2.4492 | 1.8907 | 2.6709 | 2.2095 | 3.0179 | 2.1005 | 2.1673 | 1.6612 | 1.8244 | 1.3353 | 1.4132 | 0.91815 | 1.4741 | 0.93558 | |

| Lateral | a | 2.4284 | 1.8924 | 2.6517 | 2.2113 | 2.9967 | 2.1014 | 2.1502 | 1.6636 | 1.8076 | 1.3374 | 1.3959 | 0.91978 | 1.4551 | 0.93664 |

| b | 2.2502 | 1.8925 | 2.5117 | 2.2117 | 2.823 | 2.1014 | 2.013 | 1.664 | 1.843 | 1.3369 | 1.408 | 0.9221 | 1.4831 | 0.9375 | |

| c | 2.2257 | 1.8923 | 2.4726 | 2.2112 | 2.8214 | 2.1013 | 1.9932 | 1.663 | 1.643 | 1.3367 | 1.3972 | 0.91917 | 1.4714 | 0.93544 | |

| d | 2.3838 | 1.8924 | 2.6146 | 2.2113 | 2.9622 | 2.1014 | 2.1114 | 1.6631 | 1.7729 | 1.3368 | 1.4156 | 0.91918 | 1.4824 | 0.93544 | |

| Medial | e | 2.4553 | 1.8927 | 2.6943 | 2.2119 | 3.0007 | 2.1015 | 2.1704 | 1.6646 | 1.8277 | 1.3391 | 1.4074 | 0.9227 | 1.4654 | 0.93849 |

| f | 2.4752 | 1.8908 | 2.7129 | 2.21 | 3.0218 | 2.1007 | 2.1863 | 1.6621 | 1.7101 | 1.3369 | 1.4248 | 0.92102 | 1.4867 | 0.93763 | |

| g | 2.2502 | 1.8925 | 2.5117 | 2.2117 | 2.823 | 2.1014 | 2.013 | 1.664 | 1.6638 | 1.3385 | 1.408 | 0.9221 | 1.4831 | 0.9375 | |

| h | 2.4119 | 1.8926 | 2.6574 | 2.2118 | 2.9656 | 2.1015 | 2.1336 | 1.6641 | 1.7959 | 1.3385 | 1.4268 | 0.92211 | 1.4945 | 0.93749 | |

| Sinus-tarsi | i | 2.2943 | 1.8926 | 2.549 | 2.2117 | 2.8582 | 2.1014 | 2.05 | 1.6645 | 1.6954 | 1.3391 | 1.3893 | 0.92269 | 1.4548 | 0.93851 |

| j | 2.3133 | 1.8907 | 2.5658 | 2.2099 | 2.879 | 2.1005 | 2.0648 | 1.6621 | 1.6777 | 1.3363 | 1.4079 | 0.92102 | 1.4774 | 0.93765 | |

| k | 2.291 | 1.8906 | 2.5273 | 2.2094 | 2.8769 | 2.1004 | 2.0482 | 1.6611 | 1.6941 | 1.3353 | 1.3968 | 0.91815 | 1.4651 | 0.9356 | |

| l | 2.4492 | 1.8907 | 2.5117 | 2.2117 | 2.823 | 2.1014 | 2.013 | 1.664 | 1.6638 | 1.3385 | 1.408 | 0.9221 | 1.4831 | 0.9375 | |

| Talonavi-cular | m | 2.2502 | 1.8925 | 2.5117 | 2.2117 | 2.823 | 2.1014 | 2.013 | 1.664 | 1.6638 | 1.3385 | 1.3893 | 0.92269 | 1.4831 | 0.9375 |

| n | 2.268 | 1.8907 | 2.5272 | 2.2098 | 2.8432 | 2.1006 | 2.0265 | 1.6615 | 1.6638 | 1.3385 | 1.4283 | 0.92043 | 1.5105 | 0.93665 | |

| o | 2.2444 | 1.8905 | 2.4885 | 2.2093 | 2.8417 | 2.1004 | 2.008 | 1.6606 | 1.6585 | 1.3347 | 1.4176 | 0.91756 | 1.4983 | 0.9346 | |

| p | 2.4035 | 1.8906 | 2.6325 | 2.2094 | 2.983 | 2.1006 | 2.1274 | 1.6607 | 1.7889 | 1.3347 | 1.4347 | 0.91757 | 1.5079 | 0.9346 | |

Detail procedure for removing each ligament: a: lateral ligament removal; b:removal of the lateral and medial ligaments; c: removal of the lateral ligament, medial ligament, and sinus tarsi ligament; d: removal of the lateral ligament, medial ligament, sinus tarsi ligament, and talonavicular ligament; e: removal of the medial ligament; f:removal of the medial ligament and sinus tarsi ligament; g: removal of the medial ligament, sinus tarsi ligament, and talonavicular ligament; h:removal of the medial ligament, sinus tarsi ligament, talonavicular ligament, and lateral ligament; i: removal of the sinus tarsi ligament;j: removal of the sinus tarsi ligament and talonavicular ligament; k: removal of the sinus tarsi ligament, talonavicular ligament, and lateral ligament;l: removal of the sinus tarsi ligament, talonavicular ligament, lateral ligament, and medial ligament; m: removal of the talonavicular ligament; n: removal of the talonavicular ligament and lateral ligament; o: removal of the talonavicular ligament, lateral ligament, and medial ligament; p: removal of the talonavicular ligament, lateral ligament, medial ligament, and sinus tarsi ligament

Talus Prosthesis +0 mm

The +0 mm talus prosthesis model was reconstructed without any cartilage addition. In the CT data, the gap distance between tibia and talus was halved, with one part designed as tibial cartilage added to the model and the other part as talar cartilage added to the talus. Thus, the +0 mm talus model lacks any talar cartilage addition and is distinct from the original one.

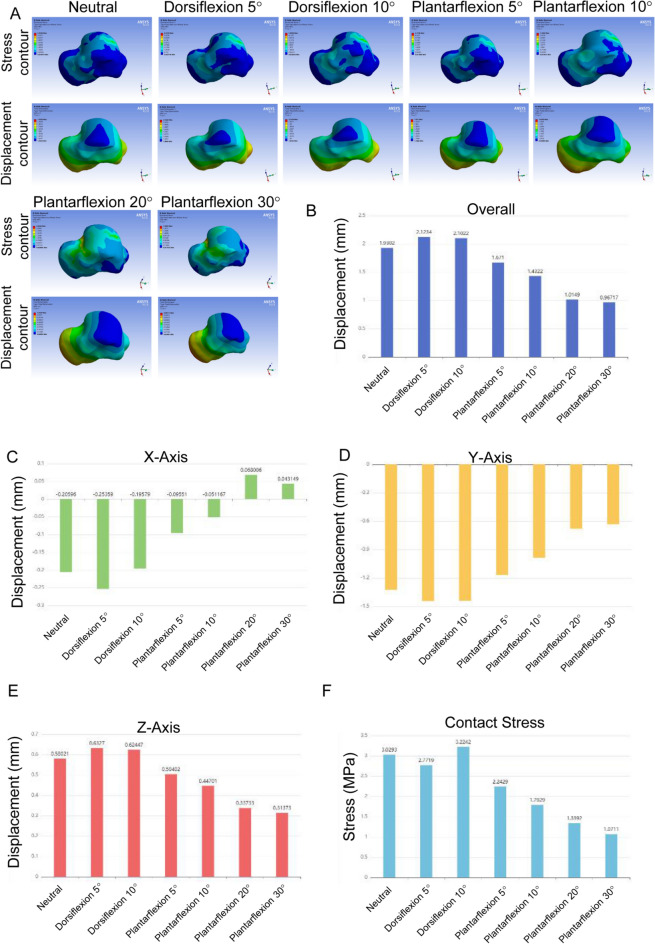

The overall displacement of the talus prosthesis showed variations across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 2B). In the neutral position, it ranged from 1.2474 to 1.7748 mm. The displacement of the talus prosthesis increased during dorsiflexion, reaching 2.0935 mm at 5° and 2.125 mm at 10°. The displacement of the talus prosthesis decreased with increasing angles: 1.524 mm at 5°, 1.549 mm at 10°, 0.97307 mm at 20°, and 0.8736 mm at 30° during plantarflexion. These results indicate that the displacement is most pronounced during dorsiflexion while it becomes not obvious during high degrees of plantarflexion.

Table 4.

Summary of talus prosthesis with different cartilage overlay displacement and contact stress

| Position | Prosthesis size (mm) | Overall displacement Max (mm) | Overall displacement Min (mm) | Contact area (mm2) | Contact stress Max (MPa) | Contact stress Min (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral | +0 | 1.7748 | 1.2474 | 480.97 | 6.61 | 0.28073 |

| +0.5 | 2.2572 | 0.011129 | 481.64 | 1.5667 | 0.11415 | |

| +1 | 1.7882 | 1.2537 | 482.82 | 3.6539 | 0.17745 | |

| +1.5 | 1.9302 | 1.3503 | 481.64 | 3.0293 | 0.3016 | |

| +2 | 1.925 | 1.3485 | 481.63 | 2.5605 | 0.32597 | |

| Dorsiflexion 5° | +0 | 2.0935 | 1.4569 | 480.11 | 2.7272 | 0.28236 |

| +0.5 | 2.1077 | 1.4699 | 480.96 | 2.6961 | 0.32898 | |

| +1 | 2.0337 | 1.432 | 480.96 | 2.595 | 0.26396 | |

| +1.5 | 2.1234 | 1.4783 | 480.97 | 2.7719 | 0.29949 | |

| +2 | 2.2326 | 1.558 | 480.94 | 2.9225 | 0.34511 | |

| Dorsiflexion 10° | +0 | 2.125 | 1.4782 | 479.86 | 3.0024 | 0.27877 |

| +0.5 | 1.9777 | 472.14 | 2.7708 | 0.24591 | ||

| +1 | 2.1261 | 1.4808 | 468.42 | 3.0038 | 0.23529 | |

| +1.5 | 2.1022 | 1.4649 | 470.55 | 3.2242 | 0.27412 | |

| +2 | 2.1046 | 1.4728 | 468.56 | 2.8961 | 0.33263 | |

| Plantarflexion 5° | +0 | 1.524 | 1.0731 | 480.94 | 2.0474 | 0.19228 |

| +0.5 | 1.5117 | 1.0633 | 468.47 | 2.0466 | 0.19608 | |

| +1 | 1.6886 | 1.1905 | 460.74 | 2.2812 | 0.22107 | |

| +1.5 | 1.671 | 1.1802 | 468.43 | 2.2429 | 0.28188 | |

| +2 | 1.5177 | 1.0677 | 468.44 | 1.009 | 0.10994 | |

| Plantarflexion 10° | +0 | 1.549 | 1.0719 | 480.93 | 2.0242 | 0.17752 |

| +0.5 | 1.15 | 0.79432 | 469.44 | 1.459 | 0.14767 | |

| +1 | 1.2161 | 0.8385 | 465.23 | 1.5661 | 0.15085 | |

| +1.5 | 1.4322 | 0.99488 | 469.46 | 1.7929 | 0.15442 | |

| +2 | 1.2174 | 0.83906 | 469.48 | 1.5694 | 0.22005 | |

| Plantarflexion 20° | +0 | 0.97307 | 0.66118 | 474.04 | 6.9746 | 0.14666 |

| +0.5 | 2.6925 | 2.0326 | 474.04 | 2.434 | 0.23683 | |

| +1 | 0.79363 | 0.55536 | 474.04 | 0.70867 | 0.099664 | |

| +1.5 | 1.0149 | 0.68882 | 474.04 | 1.3392 | 0.28732 | |

| +2 | 1.1053 | 0.75171 | 474.84 | 1.3441 | 0.25132 | |

| Plantarflexion 30° | +0 | 0.8736 | 0.57624 | 445.35 | 6.2178 | 0.18389 |

| +0.5 | 0.80259 | 0.52235 | 445.24 | 1.1884 | 0.17031 | |

| +1 | 0.90878 | 0.59854 | 445.47 | 1.371 | 0.24633 | |

| +1.5 | 0.96717 | 0.63461 | 456.99 | 1.0711 | 0.17669 | |

| +2 | 0.97152 | 0.6421 | 458.05 | 1.3744 | 0.087747 |

Fig. 2.

Displacement and contact stress analysis of talus prosthesis +0 mm. A Talus stress and displacement contour maps. B Overall Displacement. C X-Axis Displacement. D Y-Axis Displacement. E Z-Axis Displacement. F Contact Stress

Across all these positions, the contact stress is varied significantly (Table 4; Fig. 2F). In the neutral position, maximum contact stress was 6.61 MPa, with a minimum of 0.28073 MPa. During dorsiflexion, stress decreased, with maximum values of 2.7272 MPa at 5° and 3.0024 MPa at 10°. In plantarflexion, maximum stress was 2.0474 MPa at 5° and 2.0242 MPa at 10°, but increased at higher angles, reaching 6.9746 MPa at 20° and 6.2178 MPa at 30°. Minimum stress ranged from 0.19228 to 0.18389 MPa. These results indicate the impact of flexion angles on the stress distribution.

Talus Prosthesis +0.5 mm

The overall displacement of the talus prosthesis with a 0.5 mm offset showed significant variation across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 3B). In the neutral position, the displacement was 2.2572 mm. During dorsiflexion at 5° and 10°, the displacements were 2.1077 and 1.9777 mm, respectively. For plantarflexion at 5°, 10°, 20°, and 30°, the displacements were 1.5117, 1.15, 2.6925, and 0.80259 mm, respectively. This indicates that the displacement is most pronounced during dorsiflexion and plantarflexion at 20°, while the displacement changed little during high degrees of plantarflexion.

Fig. 3.

Displacement and contact stress analysis of talus prosthesis +0.5 mm. A Talus stress and displacement contour maps. B Overall Displacement. C X-Axis Displacement. D Y-Axis Displacement. E Z-Axis Displacement. F Contact Stress

The contact area was the largest in the neutral position at 481.64 mm2 (Table 4). During dorsiflexion, it slightly decreased to 480.96 mm2 at 5° and 472.14 mm2 at 10°. In plantarflexion, the contact area remained relatively stable at 468.47 mm2 and 469.44 mm2 for 5° and 10°, respectively, but decreased to 474.04 mm2 at 20° and 445.24 mm2 at 30°. These changes suggest stable contact at lower flexion angles with greater variability at higher angles. Contact stress experienced by the talus prosthesis varied across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 3F). In the neutral position, the contact stress ranged from 1.5667 to 0.11415 MPa. During dorsiflexion, stress increased, with maximum values of 2.6961 MPa at 5° and 2.7708 MPa at 10°, and corresponding minimum values of 0.32898 MPa and 0.24591 MPa. In plantarflexion, maximum stress was 2.0466 MPa at 5°, 1.459 MPa at 10°, 2.434 MPa at 20°, and 1.1884 MPa at 30°, with minimum values ranging from 0.19608 to 0.17031 MPa. These results indicate the impact of different flexion angles on stress distribution, with higher angles leading to increased stress.

Talus Prosthesis +1 mm

The overall displacement of the talus prosthesis with a 1 mm offset showed substantial variations across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 4B). In the neutral position, the displacement was 1.7882 mm. During dorsiflexion at 5° and 10°, the displacements were 2.0337 and 2.1261 mm, respectively. The displacements were changed to 1.6886, 1.2161, 0.79363, and 0.90878 mm, respectively for the plantarflexion at 5°, 10°, 20°, and 30°. This indicates that the displacement is most pronounced during dorsiflexion and has shown less significance during higher degrees of plantarflexion.

Fig. 4.

Displacement and contact stress analysis of talus prosthesis +1.0 mm. A Talus stress and displacement contour maps. B Overall Displacement. C X-Axis Displacement. D Y-Axis Displacement. E Z-Axis Displacement. F Contact Stress

The contact area was the largest in the neutral position at 482.82 mm2 (Table 4), and slightly decreased to 480.96 mm2 at 5° and 468.42 mm2 at 10° during dorsiflexion. In comparison, the contact area in plantarflexion remained relatively stable at 460.74 and 465.23 mm2 for 5° and 10°, respectively, but decreased dramatically to 474.04 mm2 at 20° and 445.47 mm2 at 30°. These changes suggest stable contact at lower flexion angles with greater variability at higher angles. The contact stress experienced by the talus prosthesis are varied across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 4F). In the neutral position, the contact stress ranged from 3.6539 to 0.17745 MPa. During dorsiflexion, the contact stress increased, with maximum values of 2.595 MPa at 5° and 3.0038 MPa at 10°, and corresponding minimum values of 0.26396 and 0.23529 MPa. In plantarflexion, the maximum stress was 2.2812 MPa at 5°, 1.5661 MPa at 10°, 0.70867 MPa at 20°, and 1.371 MPa at 30°, with minimum values ranging from 0.22107 to 0.24633 MPa. These results reveal the impact of different flexion angles on the stress distribution, with higher angles leading to increased stress.

Talus Prosthesis +1.5 mm

The overall displacement of the talus prosthesis with a 1.5 mm offset varied significantly across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 5B). In the neutral position, the displacement was 1.9302 mm. The displacements were increased to 2.1234 and 2.1022 mm, respectively during dorsiflexion at 5° and 10°. For plantarflexion at 5°, 10°, 20°, and 30°, the displacements were 1.671, 1.4322, 1.0149, and 0.96717 mm, respectively. These findings indicate that the displacement is most pronounced during dorsiflexion and least during higher degrees of plantarflexion.

Fig. 5.

Displacement and contact stress analysis of talus prosthesis +1.5 mm. A Talus stress and displacement contour maps. B Overall Displacement. C X-Axis Displacement. D Y-Axis Displacement. E Z-Axis Displacement. F Contact Stress

The contact area was the largest in the neutral position at 481.64 mm2 (Table 4), and was slightly decreased to 480.97 mm2 at 5° and 470.55 mm2 at 10° during dorsiflexion. In plantarflexion, the contact area remained relatively stable at 468.43 and 469.46 mm2 for 5° and 10°, respectively, but decreased to 474.04 mm2 at 20° and 456.99 mm2 at 30°. These changes suggest stable contact at lower flexion angles with greater variability at higher angles. The contact stress experienced by the talus prosthesis varied across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 5F). In the neutral position, the contact stress ranged from 3.0293 to 0.3016 MPa. During dorsiflexion, the stress has been increased, with the maximum values of 2.7719 MPa at 5° and 3.2242 MPa at 10°, and the corresponding minimum values of 0.29949 and 0.27412 MPa. In plantarflexion, the maximum stress was 2.2429 MPa at 5°, 1.7929 MPa at 10°, 1.3392 MPa at 20°, and 1.0711 MPa at 30°, with the minimum values ranging from 0.28188 MPa to 0.17669 MPa. These results indicated the impact of different flexion angles on stress distribution, with higher angles leading to increased stress.

Talus Prosthesis +2 mm

The overall displacement of the talus prosthesis with a 2 mm offset showed substantial variations across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 6B). In the neutral position, the displacement was 1.925 mm, and were increased to 2.2326 and 2.1046 mm, respectively during dorsiflexion at 5° and 10°. For plantarflexion at 5°, 10°, 20°, and 30°, the displacements were 1.5177, 1.2174, 1.1053, and 0.97152 mm, respectively. These findings indicate that the displacement is most pronounced during dorsiflexion and least during higher degrees of plantarflexion.

Fig. 6.

Displacement and contact stress analysis of talus prosthesis +2.0 mm. A Talus stress and displacement contour maps. B Overall Displacement. C X-Axis Displacement. D Y-Axis Displacement. E Z-Axis Displacement. F Contact Stress

The contact area was largest in the neutral position at 481.63 mm2 (Table 4). During dorsiflexion, it slightly decreased to 480.94 mm2 at 5° and 468.56 mm2 at 10°. In plantarflexion, the contact area remained relatively stable at 468.44 and 469.48 mm2 for 5° and 10°, respectively, but decreased significantly to 474.84 mm2 at 20° and 458.05 mm2 at 30°. These changes suggest stable contact at lower flexion angles with greater variability at higher angles. The Contact stress experienced by the talus prosthesis varied across different positions (Table 4; Fig. 6F). In the neutral position, the contact stress ranged from 2.5605 to 0.32597 MPa. During dorsiflexion, the stress increased, with maximum values of 2.9225 MPa at 5° and 2.8961 MPa at 10°, and corresponding minimum values of 0.34511 and 0.33263 MPa. In plantarflexion, maximum stress was 1.009 MPa at 5°, 1.5694 MPa at 10°, 1.3441 MPa at 20°, and 1.3744 MPa at 30°, with minimum values ranging from 0.10994 to 0.087747 MPa. These results reveal the impact of different flexion angles on stress distribution, with higher angles leading to increased stress.

Achieving biomechanical compatibility with a 0.5 mm overlay

The effects of different cartilage thicknesses on contact area and contact stress across various flexion angles were compared to determine the optimal prosthesis design for biomechanical compatibility (Fig. 7A). The contact area remained consistent during neutral and dorsiflexion (5° and 10°) regardless of cartilage thickness. The obvious reductions of contact area were obtained at higher plantarflexion angles (20° and 30°) with thinner cartilage layers (0–1.5 mm) (Fig. 7A). Specifically, at 30° of plantarflexion, the thinnest cartilage (+0 mm) resulted in the lowest contact area, while thicker layers maintained a more stable area.

Fig 7.

Impact of cartilage thickness on contact area and stress across flexion angles. A Bar graph showing the contact area (mm2) across neutral, dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion angles with different cartilage thicknesses (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 mm). B Bar graph displaying contact stress (MPa) across the same positions and cartilage thicknesses

The contact stress was compared across various flexion angles and cartilage thicknesses. The contact stress, on the other hand, was highly sensitive to cartilage thickness, with the thinnest cartilage producing significantly higher contact stresses across all angles, particularly at 20° and 30° of plantarflexion (Fig. 7B). The thickest cartilage (+2 mm) led to a more moderate increase in stress, but the most balanced distribution of stress, approximating to the normal ankle joint, was observed with a 0.5 mm cartilage overlay. This layer maintained lower stress values while ensuring an adequate contact area.

Among the different cartilage thicknesses tested, the 0.5 mm cartilage overlay on the talus prosthesis most closely approximates the stress distribution of a normal ankle joint. This finding underscores the importance of optimizing cartilage thickness in prosthesis design to enhance biomechanical compatibility and improve functional outcomes.

Discussion

A talus prosthesis is a medical device used to replace the talus bone in the ankle, typically due to severe injury or degenerative diseases [28]. This prosthesis is crucial for restoring ankle function and alleviating pain. Exploring the stability and stress distribution changes in the talus prosthesis is essential for ensuring its long-term success and functionality. This study is mainly using the FEA to simulate the physical status of Talus Prosthesis. In this study, FEA was conducted using linear, isotropic elastic material properties for both bone tissue and implant models. Failure criteria such as von Mises, Tresca, or Principal stresses, which are typically utilized for assessing plastic deformation or fracture in non-linear materials, were not applied. Since our objective was to compare the stress distributions among different implant configurations rather than to predict material failure, the application of failure theories based on plastic or brittle behavior was not appropriate. Therefore, the analysis focused on relative stress patterns under elastic assumptions. Validation study has confirmed the reliability of FEA in predicting contact stress distributions, as shown by the good agreement between FE-computed and experimentally measured contact stress and area [29–34].

The finite element model predicted a contact area of 496.39 mm2 and a peak contact pressure of 2.7681 MPa, closely matching previously reported ranges of 453–527 mm2 for contact area and 2.7–4.0 MPa for peak contact pressure [26]. In our finite element model, the predicted contact area was 496.39 mm2, and the peak contact pressure was 2.7681 MPa. These results fall well within the experimental range, indicating that our model achieved a high degree of accuracy in replicating the mechanical behavior of the ankle joint.

This study found that the removal of the surrounding ligaments does not significantly compromise the stability of the talus prosthesis. It implies that even with the gradual removal of supportive structures, the prosthesis can maintain its functional integrity, making it a reliable option for patients requiring talus replacements. In 2015, Taniguchi et al reported that the mean talar tilt angle on inversion/eversion stress position of patients after the replacement of talus prosthesis was 5.0° and 1.1°, respectively, the mean anterior drawer distance was 1.4 mm, which indicates stability of bare talus prostheses without ligament reconstruction or subtalar joint fusion [6]. Different clinical studies have shown that bare talus prosthesis can significantly improve clinical symptoms while rebuilding limb height [35, 36].

The stress distribution analysis revealed that the application of different cartilage thicknesses significantly affects the joint surface stress distribution. Notably, the prosthesis with a 0.5 mm cartilage overlay exhibited stress patterns that closely resemble those of a normal ankle joint. For the prosthesis without any cartilage overlay (0 mm), the stress distribution showed higher peak stresses, particularly during dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. This indicates a higher likelihood of localized stress concentrations, which could potentially lead to wear and tear or other mechanical failures over time. In contrast, the prosthesis with thicker cartilage overlays (1, 1.5, and 2 mm) demonstrated varying degrees of stress distribution improvement. However, these modifications did not achieve the same level of stress normalization as the 0.5 mm overlay. The 0.5 mm cartilage overlay appears to provide the best balance between stress distribution and mechanical stability, suggesting that this thickness should be considered in future prosthesis designs and implementations. It has been found that pre-exercise cartilage thickness varied significantly by location within the talus, but not within the tibia [37]. Another finite element analysis indicated that under identical loading conditions, thicker cartilage experiences lower peak contact stress compared to thinner cartilage [38]. However, overly thick layers can result in uneven stress distribution, supporting our finding that the 0.5 mm thickness offers an optimal balance.

This study presents a novel contribution as it is the first to systematically evaluate the impact of cartilage coverage thickness on joint stress distribution in total talar replacement. Although isotropic and idealized material properties were used, this approach remains necessary because current technology cannot fully replicate the complex mechanical behaviors and microstructural interactions of biological tissues. As such, certain simplifications are inevitable to ensure the feasibility of finite element simulations. The results, therefore, offer valuable qualitative and quantitative guidance for prosthesis design despite these approximations.

While this study provides important insights in the design and customization of talus prostheses, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. The FEA approach, while powerful, relies on assumptions and idealizations that may not fully capture the complexities of in vivo conditions. For instance, the study assumes static loading conditions, with a 500 N vertical load applied to the plantar surface, simulating physiological standing conditions. This approach does not account for the dynamic nature of loading, where forces on the joint vary during activities such as walking or running, potentially leading to a different weight distribution that was not considered in the current model. Future simulations should consider the variation in load distribution during different movements, such as walking or running, to better reflect the full range of physiological activities. The absence of surrounding ligaments in the model further limits the study’s applicability, as ligaments play a crucial role in joint stability and movement in real-world scenarios. Additionally, the study did not account for long-term biomechanical adaptations or potential biological responses to the prosthesis and cartilage overlays. Only the stress changes on the talar articular surface were analyzed, while surrounding joints such as the subtalar and talonavicular joints were not assessed. This focus was chosen because preserving tibiotalar joint function is the primary goal after total talar replacement, and sagittal plane movements mainly occur at this joint. Future research should focus on validating these findings through experimental and clinical studies, involving long-term follow-ups to assess the durability and performance of the prosthesis with different cartilage thicknesses. Moreover, exploring the effects of dynamic loading conditions and incorporating patient-specific variations could further enhance the applicability and reliability of the results. Lastly, regarding stress analysis in specific tangential planes (XY, YZ, ZX), since our models represent intact bone without fracture gaps, ANSYS does not directly allow planar section stress extraction. This limitation restricted our ability to provide a detailed sectional stress distribution analysis. Future studies incorporating fracture models or more advanced extraction techniques could address this issue.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that removal of the surrounding ligaments does not significantly affect the mechanical stability of the talus within the ankle mortise, nor does it substantially alter the stress distribution on the articular surfaces. Among the prosthetic designs tested, a 0.5 mm cartilage overlay most closely replicated the stress distribution of a normal ankle, indicating the importance of optimizing cartilage thickness to enhance biomechanical performance.

This study is limited to static loading conditions and simplified sagittal plane movements, specifically dorsiflexion, neutral position, and plantarflexion. Full gait simulation was not included, as patients undergoing total talus replacement often do not recover full motion, and the absence of reattached ligaments around the prosthesis limits complex joint dynamics such as rotation and inversion or eversion.

Future research should incorporate dynamic loading scenarios and patient-specific data. In particular, gait analysis data from postoperative total talus replacement patients, combined with CT scans captured at different gait phases, can be used to build more realistic finite element models. Applying phase-specific dynamic loads would enable more accurate evaluation of prosthesis function under real-world conditions and contribute to further optimization of talus prosthesis design.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for the technical support provided by Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Intelligent Medicine [2024A03J0847].

Author contributions

Weidong Song, Huiying Zhao and Yue Ding designed and supervised the experiments. Gang Zeng, Yujun Sun, Min Liang, Wenzhou Liu, Yanbo Chen, Jionglin Wu, Jiayuan Zheng and Taolue Zhou conducted the experiments. Gang Zeng, Yujun Sun and Min Liang acquired and analyzed the data. Gang Zeng and Yue Ding wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou [2023A03J0705]; the Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Intelligent Medicine [2024A03J0847].

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (No. 2022-QX-009). Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gang Zeng, Yujun Sun and Min Liang contributed equally to this work and should be considered as the co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Huiying Zhao, Email: Zhaohy8@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Weidong Song, Email: songwd@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yue Ding, Email: dingyue@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Reference

- 1.West TA, Rush SM. Total talus replacement: case series and literature review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(1):187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennison T, et al. Total talus replacements. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023;8(1):24730114221151068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockett CL, Chapman GJ. Biomechanics of the ankle. Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(3):232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R, et al. Ankle and foot arthroplasty and prosthesis: a review on the current and upcoming state of designs and manufacturing. Micromachines (Basel). 2023;14(11):2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abar B, et al. Initial safety of total talus replacement used to treat talar avascular necrosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2024;45(11):1258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taniguchi A, et al. An alumina ceramic total talar prosthesis for osteonecrosis of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(16):1348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taniguchi A, et al. The use of a ceramic talar body prosthesis in patients with aseptic necrosis of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11):1529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Hoogstraten SWG, et al. Malalignment of the total ankle replacement increases peak contact stresses on the bone-implant interface: a finite element analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, et al. Influence of clearance on the time-dependent performance of the hip following hemiarthroplasty: a finite element study with biphasic acetabular cartilage properties. Med Eng Phys. 2014;36(11):1449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoji H, et al. Kinematics and laxity of the ankle joint in anatomic and nonanatomic anterior talofibular ligament repair: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(3):667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larkins CG, et al. Evaluation of the intact anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments, injuries, and repairs with and without augmentation: a biomechanical robotic study. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(9):2432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, et al. Function of ankle ligaments for subtalar and talocrural joint stability during an inversion movement - an in vitro study. J Foot Ankle Res. 2019;12:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takao M, et al. Strain pattern of each ligamentous band of the superficial deltoid ligament: a cadaver study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weindel S, et al. Subtalar instability: a biomechanical cadaver study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(3):313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pellegrini MJ, et al. Systematic quantification of stabilizing effects of subtalar joint soft-tissue constraints in a novel cadaveric model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(10):842–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saha S, Roychowdhury A. Application of the finite element method in orthopedic implant design. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2009;19(1):55–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghili SA, Hassani K, Nikkhoo M. A finite element study of fatigue load effects on total hip joint prosthesis. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2021;24(14):1545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kladovasilakis N, Tsongas K, Tzetzis D. Finite element analysis of orthopedic hip implant with functionally graded bioinspired lattice structures. Biomimetics (Basel). 2020;5(3):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loi I, Stanev D, Moustakas K. Total knee replacement: subject-specific modeling, finite element analysis, and evaluation of dynamic activities. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9: 648356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis GS, et al. Finite element analysis of fracture fixation. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2021;19(4):403–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu C, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of tenodesis reconstruction in ankle with deltoid ligament deficiency: a finite element analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1854–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stauffer RN, Chao EY, Brewster RC. Force and motion analysis of the normal, diseased, and prosthetic ankle joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;127:189–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song K, et al. Acute talar cartilage deformation in those with and without chronic ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(6):1228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockard CA, et al. Accuracy of MRI-based talar cartilage thickness measurement and talus bone and cartilage modeling: comparison with ground-truth laser scan measurements. Cartilage. 2021;13(1_suppl):674S-684S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demirci S, et al. Chondral thickness and radii of curvature of the femoral condyles and talar trochlea. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29(4):327–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson DD, et al. Physical validation of a patient-specific contact finite element model of the ankle. J Biomech. 2007;40(8):1662–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell TG, Byerly DW. Talus fracture. In: StatPearls. StatPearls: Treasure Island (FL); 2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonetti D, et al. Total talar prosthesis, learning from experience, two reports of total talar prosthesis after talar extrusion and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(8):1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiapour A, et al. Finite element model of the knee for investigation of injury mechanisms: development and validation. J Biomech Eng. 2014;136(1): 011002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naoum S, et al. Finite element method for the evaluation of the human spine: a literature overview. J Funct Biomater. 2021;12(3):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang R, Wu Z. Recent advancement in finite element analysis of spinal interbody cages: A review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1041973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim WH, et al. Optimized dental implant fixture design for the desirable stress distribution in the surrounding bone region: a biomechanical analysis. Materials (Basel). 2019;12(17):2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy MS, Sundram R, Eid Abdemagyd HA. Application of finite element model in implant dentistry: a systematic review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(Suppl 2):S85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ying J, et al. Biomechanical insights into ankle instability: a finite element analysis of posterior malleolus fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morita S, et al. The long-term clinical results of total talar replacement at 10 years or more after surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104(9):790–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadakia RJ, et al. 3D printed total talus replacement for avascular necrosis of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(12):1529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cher WL, et al. An analysis of changes in in vivo cartilage thickness of the healthy ankle following dynamic activity. J Biomech. 2016;49(13):3026–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li G, Lopez O, Rubash H. Variability of a three-dimensional finite element model constructed using magnetic resonance images of a knee for joint contact stress analysis. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123(4):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.