Abstract

Regardless of their sex chromosome karyotype, amniotes develop two pairs of genital ducts, the Wolffian and Müllerian ducts. As the Müllerian duct forms, its growing tip is intimately associated with the Wolffian duct as it elongates to the urogenital sinus. Previous studies have shown that the presence of the Wolffian duct is required for the development and maintenance of the Müllerian duct. The Müllerian duct is known to form by invagination of the coelomic epithelium, but the mechanism for its elongation to the urogenital sinus remains to be defined. Using genetic fate mapping, we demonstrate that the Wolffian duct does not contribute cells to the Müllerian duct. Experimental embryological manipulations and molecular studies show that precursor cells at the caudal tip of the Müllerian duct proliferate to deposit a cord of cells along the length of the urogenital ridge. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis reveals that the cells of the developing Müllerian duct are mesoepithelial when deposited, and subsequently differentiate into an epithelial tube and eventually the female reproductive tract. Our studies define cellular and molecular mechanisms for Müllerian duct formation.

Keywords: Müllerian duct, paramesonephric duct, Wolffian duct, mesonephric duct, nephric duct, tubulogenesis, cell proliferation

Introduction

Amniotes regardless of their genetic sex form two separate and distinct genital ducts, the Wolffian and Müllerian ducts, during embryonic development. In mammals, the former differentiates into the male reproductive tract, the vas deferentia, epididymides and seminal vesicles, whereas the latter develops into the female reproductive tract consisting of the oviducts, uterus and upper third of the vagina. Initially, the Wolffian ducts form from the intermediate mesoderm (Jacob et al., 1991; Obara-Ishihara et al., 1999) and in the mouse, its development is complete by embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5). Johannes Müller first described the Müllerian duct in human and chick embryos in 1830 and beginning with its first description, the mechanism for Müllerian duct growth has been controversial.

It was noted that during development, the Müllerian duct is intimately associated with the Wolffian duct. At its caudal growing tip, the forming Müllerian duct is in physical contact with the Wolffian duct and was believed to be located inside the basement membrane of the Wolffian duct. Due to this tight association, Balfour and Sedgewick (1879) believed that the cells of the Müllerian duct were derived from cells of the Wolffian duct. This belief was further supported by Gruenwald (1937) who showed that experimental interruption of the Wolffian duct in the chick resulted in incomplete formation of the Müllerian duct at the point of Wolffian duct interruption. Despite this evidence, others believed that the Wolffian duct did not contribute cells to the Müllerian duct, but simply acted as a guide. Dohr et al. (1987) demonstrated a difference in antigen expression between Wolffian duct and Müllerian duct cells, suggesting that the Wolffian duct does not contribute cells to the developing Müllerian duct. This, however, was based on the assumption that if a Wolffian duct cell transformed into a Müllerian duct cell, some antigen expression would persist and still be observed. Many studies have attempted to define the mechanism for the development of the Müllerian duct (Dohr et al., 1987; Gruenwald, 1941; Jacob et al., 1999; Potemkina et al., 1971), but to date; this mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Development of the Müllerian duct is considered biphasic, with the first phase consisting of an invagination of the coelomic epithelium through the mesonephros and the second phase an elongation of the Müllerian duct caudally to the urogenital sinus (Gruenwald, 1941). In the first phase, cells of the coelomic epithelium are specified to a Müllerian duct fate through an unknown mechanism. This specification can be identified by the expression of Lim1 in cells of the coelomic epithelium (Kobayashi et al., 2004). After specification, Wnt4 expression in the mesenchyme from the mesonephros or coelomic epithelium, induces the invagination of these specified cells (Kobayashi et al., 2004; Vainio et al., 1999). This first phase of Müllerian duct development is Wolffian duct independent (Carroll et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2005). The first phase ends when the invaginating Müllerian duct extends to and contacts the Wolffian duct where the second phase begins.

It is during this second phase that most studies have been performed. In this elongation phase, the presence of the Wolffian duct is required for development of the Müllerian duct. This dependence has been shown both in vitro and in vivo. As described above, when the Wolffian duct is disrupted at a specific point in ovo, the Müllerian duct is unable to grow past that point (Gruenwald, 1937). Lim1 was shown to be necessary for maintenance of the Wolffian duct and conditional inactivation results in loss of the Wolffian duct epithelium. Due to the dependence of the Müllerian duct on the Wolffian duct, loss of Lim1 in the Wolffian duct also results in incomplete development of the Müllerian duct (Kobayashi et al., 2005). The Müllerian ducts of mice mutant for the Pax2 gene invaginate from the coelomic epithelium, but do not elongate due to degeneration of the Wolffian duct (Miyamoto et al., 1997; Torres et al., 1995). Finally, genetic evidence has shown that the Wolffian duct may not only act as a physical guide or contribute cells to the Müllerian duct, but also provides a necessary signal for its elongation. Wnt9b is expressed by the Wolffian duct epithelium and the loss of this gene results in incomplete development of the Müllerian duct (Carroll et al., 2005). When expression of Wnt9b was lost, the Müllerian duct was able to properly invaginate from the coelomic epithelium, but could not extend caudally, suggesting that the Wolffian duct is not required for the first phase of growth. Also, loss of Wnt9b did not affect the Wolffian duct itself, therefore, the Wolffian duct signals, through Wnt9b, to the developing Müllerian duct leading to the second phase of Müllerian duct development.

There are many ways in which an epithelial tube can be generated. Tubes can form through a mechanism of wrapping in which cells of an epithelium invaginate in a line and pinch off forming a separate tube, as does the vertebrate neural tube (Colas, 2001; Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003). Tubes can bud off from a larger tube forming a branching organ like the mammalian lung (Metzger, 1999) or the Drosophila tracheal system (Hogan and Kolodziej, 2002; Wilk et al., 1996). In these mechanisms, tubes are generated from an already polarized epithelium. Cells can change fate when subjected to certain factors, such as the mesenchymal to epithelial transition of the mammalian metanephric kidney and Wolffian duct (Jacob et al., 1991; Karavanova et al., 1996). Cavitation is a process in which a cylindrical mass of cells forms a lumen by eliminating cells in the center of the mass (Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003). A cord of two cells can hollow forming a lumen and even one cell can form a lumen by generating an apical and basal polarity within itself (Wolff, 1972). Interestingly, in all of these cases, no tubule requires the presence of another separate and distinct epithelial tube for its morphogenesis.

In this study, we investigated the mechanisms of Müllerian duct development. We show that the Wolffian duct does not contribute cells to the developing Müllerian duct, but rather, formation of the Müllerian duct is accomplished by cell proliferation. We also examined the character of both the Wolffian and Müllerian ducts. We show that while the Wolffian duct is a true epithelial tube, the developing Müllerian duct is mesoepithelial in character and subsequently differentiates into an epithelial tube. Taken together, these data indicate that the developing Müllerian duct accomplishes its elongation predominantly by proliferation of a small group of cells located at its distal tip, guided by the Wolffian duct.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Lim1lz/+ mice (Kania et al., 2000) were maintained on a C57BL/6; 129/SvEv mixed genetic background. Lim1lz/+ males were bred to Swiss females (Charles River Laboratories). Noon on the day of the vaginal plug was considered embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5) and tail somite numbers were used to stage embryos (Hacker et al., 1995). Hoxb7-Cretg/+ mice (Yu et al., 2002) were maintained on a C57BL/6 congenic background and R26R mice (Soriano, 1999) on a C57BL/6; 129/SvEv mixed genetic background.

Embryo sex genotyping

Embryos were sexed by Barr body staining of amnions. Amnions were placed in eppendorf tubes and fixed in 3:1 Methanol:Glacial Acetic Acid until all embryos were collected. The fixative was removed and 50 μL of 60% Glacial Acetic Acid was added. The tubes were vortexed to dissolve the amnion and the tube was filled with fixative. The cells were then spun at 5000rpm for 3 min and inverted to remove supernatant. The cells were vortexed to resuspend and pipetted onto coverslips. 25 μL of 1% Toluidine Blue was added and the coverslips placed onto slides. The slides were then analyzed for the presence or absence of Barr bodies.

Tissue preparation and histology

X-gal staining was performed as described (Nagy, 2003). Tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) overnight, dehydrated through a series of ethanols and embedded in paraffin for histological sectioning. The paraffin embedded wild-type tissue was sectioned at 5 μM and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining or immunohistochemistry. X-gal stained tissue was sectioned at 12 μM and counterstained with 0.33% Eosin Y. Measurements of Müllerian duct length were performed using the measure tool in Adobe Photoshop.

Immunohistochemistry/flourescence

Sectioned urogenital ridges were deparaffinized with xylenes and rehydrated through a series of ethanols to water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was destroyed using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 minutes and washed with water. Antigen recovery was performed by boiling samples in 0.01M Sodium Citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes and washed 3 times in PBS. Samples were blocked for 30 minutes in 5% bovine serum albumin for vimentin and phospho-Histone H3 (pH3) and 1.5% normal horse serum for cytokeratin 8 immunostaining. Goat anti-vimentin (Sigma, V 4630), rabbit anti-pH3 (Millipore, 06-570) and rat anti-cytokeratin 8 (Sigma, TROMA-1) were used at dilutions 1:40, 1:200 and 1:80, respectively and incubated overnight. An anti-universal/anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) was used for vimentin and cytokeratin 8 immunostaining at a dilution of 1:250 and an anti-rabbit secondary antibody at 1:250 for pH3 for 30 minutes. All samples were washed 3 times in PBS and incubated with ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes. Enzymatic detection was performed with AEC solution and samples were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Immunohistochemistry using mouse anti-pan cytokeratin (Sigma, C1801) was performed with the VECTOR M.O.M. Immunodetection Kit (Vector Laboratories), according to manufacturer's instructions. For E-Cadherin immunoflourescence, sections were deparaffinized and hydrated. Antigen recovery was performed using DAKO Target Retrieval Solution (S1699) by boiling for 20 minutes and blocked with DakoCytomation Protein Block (X0909) for 30 minutes. Mouse anti-E-cadherin (BD Biosciences, 610181) was used at a dilution of 1:200 for one hour and washed 3 times in PBS. An Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse (Molecular Probes, A-11001) was used at a dilution of 1:800 for one hour and washed twice with PBS. Sections were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, H1200). At E12.5, BrdU (Amersham) was given to pregnant Swiss females by intraperitoneal injection at 0.02 cc/g body weight. After a two-hour pulse, embryos were collected and BrdU immunohistochemistry was performed (Calbiochem) as per manufacturer's instructions. At least three embryos were analyzed for each antigen.

Urogenital ridge recombinant explant culture and Müllerian duct tip formation assay

In vitro culture was performed with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (GIBCO #430-2100EB) supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum, 0.01 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM glutamine and 0.005 mg/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Embryos were dissected in media containing 20 mM HEPES. Lim1lz/+ × Swiss embryos were sacrificed at ∼ E11.75 corresponding to tail somite (TS) 19-21. Embryos were separated at the level of the liver, leaving anterior and posterior halves. The anterior half of the embryo was removed and placed unfixed in X-gal stain at 37°C. The urogenital ridge was removed from the posterior half of the embryo using straight and curved forceps. Once genotyped by X-gal staining of the anterior half of the embryo, Lim1lz/+ and wild-type urogenital ridges were cut in half using tungsten needles creating a rostral and caudal half. The gonad was used as a reference point and the cut was made through the middle of the gonad. The rostral half of the urogenital ridge from a Lim1lz/+ embryo was placed onto an agar block with the caudal half from a wild-type embryo and vice versa. The halves were then manipulated so that they were aligned with each other and were cultured for three days. Media was changed daily and on the third day, the ridges were fixed in 4% PFA, stained for lacZ using X-gal and analyzed for the ability of the Müllerian ducts to grow into the caudal half ridge.

All in vitro steps of the Müllerian duct tip formation assay were performed as described above with the exception of the culture lasting two days. Lim1lz/+ embryos were collected at ∼E12.5 and urogenital ridges dissected. One side of the urogenital ridge was cut rostral of the growing Müllerian duct tip, removed from the urogenital ridge by a second vertical cut and discarded. At this stage, a bulge at the lateral edge of each urogenital ridge easily detects the Müllerian duct. Only the left side of the urogenital ridge was removed as the other side served as a positive control.

Results

Timing the initiation and completion of Müllerian duct formation in the mouse

The Müllerian duct is described in the mouse as developing from E11.5 to 13.5 (Kaufman, 1999; Kobayashi et al., 2004). We investigated the precise timing of Müllerian duct formation using tail somites (TS) as a marker of developmental stage. Since somite developmental timing has been well studied (Gossler, 2002), we utilized this to measure Müllerian duct initiation and elongation in both males and females. For Müllerian duct development to occur, cells of the coelomic epithelium must first be specified to become Müllerian duct cells (Jacob et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 2004). These specified cells are first detected at TS19 (∼E11.75) by the expression of Lim1lz/+ (Fig. 1A and B)(Jacob et al., 1999). By TS22 (∼E12.0), the Müllerian duct has completed the first phase and contacted the Wolffian duct (Fig. 1C and D). At this stage, the growing Müllerian duct tip is in contact with the Wolffian duct and all subsequent development is dependent upon the presence of the Wolffian duct. At TS28 (∼E12.5) the duct has grown half the distance to the urogenital sinus where it will begin crossing over the Wolffian duct to become located medially (Fig. 1E and F, Fig. 2A, C and D). This crossover occurs at the level of the caudal region of the developing gonad (Fig. 2A). We were also interested in the rate of Müllerian duct development and therefore took measurements of the Müllerian duct at TS22 and TS28 (Supplemental Table 1). By utilizing tail somite development, which is said to occur every 2-3 hours (Gossler, 2002), we were able to determine the rate at which the Müllerian duct develops. By TS22, the average length of the Müllerian duct was ∼450 μM. This would indicate that during the invagination phase, the Müllerian duct develops at a rate of 50 to 75 μM per hour. At TS28, the average length of the Müllerian duct was ∼870 μM. During the elongation phase, from TS22 to TS28, the Müllerian duct develops at a rate of 24 to 35 μM per hour. Elongation of the Müllerian duct is complete by TS34 (∼E13.5) when the duct has reached the urogenital sinus (Fig. 1G and H). Analysis indicates that development of the Müllerian duct is independent of sex as no differences are observed in the duct between males and females at these stages. However, by TS34, differences in the Wolffian duct were observed (Fig. 1G and H). Maintenance of the Wolffian duct requires production of testosterone from fetal Leydig cells (Drews, 1998) and in the female at TS34, the Wolffian duct has started its passive regression through the loss of cells as noted by the loss of Lim1lz/+ expression when compared to that in the male (Fig. 1G and H).

Fig. 1.

Staging Müllerian duct development. Lim1lz/+ expression in the Wolffian duct and growing Müllerian duct of females (A, C, E, G) and males (B, D, F, H). Whole mount lateral view (A and B) and ventral view (C-H) of Lim1lz/+ urogenital ridges. Müllerian duct precursor cells arise from the coelomic epithelium at tail somite 19 (TS19) in both females (A) and males (B). By TS22, both females (C) and males (D) have accomplished Müllerian duct invagination from the coelomic epithelium and contacted the Wolffian duct. The Müllerian duct has completed half of its elongation to the urogenital sinus at TS28 (E, F) and reached the urogenital sinus by TS34 (G, H). k, kidney (metanephros); md, Müllerian duct; mt, mesonephric tubules; o, ovary; t, testis; wd, Wolffian duct. Scale bar: 200 μM in A-D; 500 μM in E-H.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of growing Müllerian duct in relation to Wolffian duct at E13.0 in a male embryo. Whole mount urogenital ridge of a Lim1lz/+ embryo (A). (B-F) Cross-section of age matched wild-type embryo stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In the most rostral region, mesenchymal cells that form a sworl pattern surround the Müllerian duct (B). The Müllerian duct is located lateral in relation to the Wolffian duct (B). At E13.0, the Müllerian duct has crossed over the Wolffian duct to become located medially in relation to the Wolffian duct (C, D, E). (C, D) The Müllerian duct is separated from the Wolffian duct by mesenchymal cells, but these mesenchymal cells do not yet form a sworl around the Müllerian duct. Just rostral of the growing tip, the Müllerian duct is separated from the Wolffian duct (E). At the growing tip, cells of the Müllerian duct are in physical contact with cells of the Wolffian duct (F). g, gonad; md, Müllerian duct; wd, Wolffian duct. Scale bar: 20 μM.

Development of the Müllerian duct occurs in a rostral to caudal manner with a group of cells at the most caudal tip being tightly associated with the Wolffian duct (Fig. 2F). Here, cells of the growing Müllerian duct tip are in physical contact with cells of the Wolffian duct and except for the invaginvation phase, the tip cells are always tightly associated with the Wolffian duct spanning 15-20 μM (data not shown). This observation contributed to the conclusion by Balfour and Sedgewick that the Wolffian duct supplied cells to the developing Müllerian duct. Once the Müllerian duct tip has deposited cells and moved caudally, physical contact with the Wolffian duct is lost. The two ducts are still associated with one another, but are separated by a basement membrane. (Fig. 2E)(Gruenwald, 1941; Gruenwald, 1943). Mesenchymal cells then appear between the Müllerian duct and Wolffian duct and Müllerian duct and coelomic epithelium (Fig. 2C and D) and eventually, in the most rostral region, form the “sworl” pattern around the duct that is indicative of the beginning of male Müllerian duct regression (Fig. 2B)(Dyche, 1979). The mesenchymal cells that contribute to this pattern are those expressing Amhr2 and are responsible for transducing the Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) signal leading to regression of the Müllerian duct (Mishina et al., 1999).

The developing Müllerian duct is mesoepithelial in character

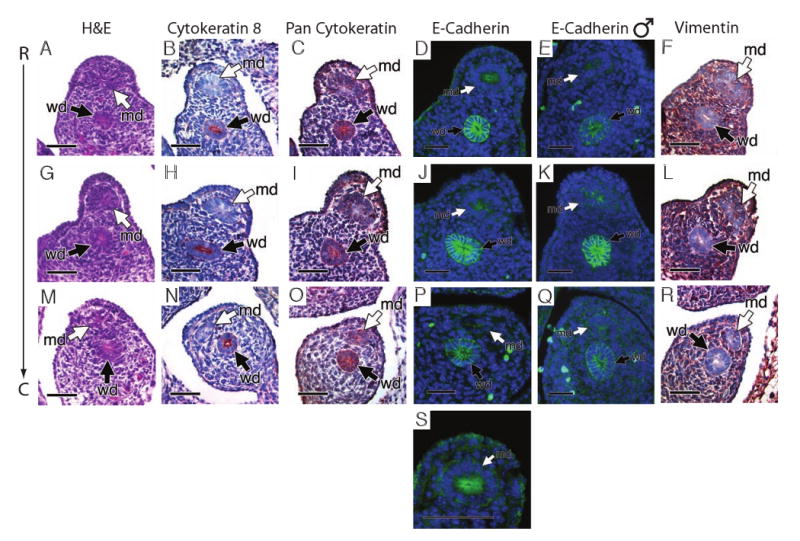

We investigated the nature and character of the growing Müllerian duct by visualization of epithelial and mesenchymal cell markers. We performed immunohistochemical analysis in both males and females at E12.5 (Fig. 3) and E13.5 (Fig. 4) for cytokeratin 8, pan cytokeratin and E-cadherin, markers of epithelium, as well as vimentin, a marker of mesenchyme. We analyzed three separate levels of the Müllerian duct from rostral to caudal.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis at E12.5 in wild-type tissue. The Müllerian duct was analyzed at three separate regions; rostral to the growing tip (A, B, C, D, E), at the growing tip (F, G, H, I, J) and caudal to the tip (K, L, M, N, O). (A, F, K) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Cytokeratin 8, a marker of epithelium, was detected in the Wolffian duct, but not the developing Müllerian duct (B, G, L) as well as E-cadherin (D, I, N). The Wolffian duct also expressed pan-cytokeratin and the Müllerian duct showed weak expression (C, H, M). The Müllerian duct expresses vimentin, a marker of mesenchyme, at both its caudal tip and rostral region while the Wolffian duct does not express vimentin (E, J, O). High magnification of the vimentin stained tip reveals high expression of vimentin in the cells of the Müllerian duct tip (P). c, caudal; md, Müllerian duct; r, rostral; wd, Wolffian duct. Scale bar: 20 μM in A-O, 10μM in P.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of XX (A-D, F-J, L-P, R, S) and XY (E, K, Q) embryos at E13.5 in wild-type tissue. The Müllerian duct was analyzed at three separate regions, rostral (A, B, C, D, E, F), middle (G, H, I, J, K, L) and caudal (M, N, O, P, Q, R). (A, G, M) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. The Wolffian duct, but not Müllerian duct expresses the epithelial marker cytokeratin 8 (B, H, N). Expression of pan-cytokeratin can be detected in the Wolffian duct and weakly in the Müllerian duct (C, I, O). The Müllerian duct weakly expresses the mesenchymal marker, vimentin, which is not expressed by the Wolffian duct (F, L, R). The Wolffian duct also expresses the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin in both males and females (D, E, J, K, P, Q). High magnification in a female embryo (S) reveals the most rostral portion of the Müllerian duct is expressing E-cadherin in its apical region, which is not seen in the male (E). c, caudal; md, Müllerian duct; r, rostral; wd, Wolffian duct. Scale bar: 20 μM in A-R, 10μM in S.

At E12.5, the entire length of the Wolffian duct can be considered a true epithelial tube due to its expression of cytokeratin 8, pan cytokeratin and E-cadherin and lack of expression of vimentin (Fig 3). Cytokeratin 8 is localized to all regions of the epithelial cell, apical, lateral and basal (Fig. 3B, G and L). Pan cytokeratin expression mirrors that of cytokeratin 8 with apical, lateral and basal localization (Fig. 3C, H and M), while vimentin expression is not observed (Fig. 3E, J and O). These results are furthermore supported by the expression of E-cadherin in the Wolffian duct (Fig. 3D, I, N). At this stage, the coelomic epithelium stains positive for all four markers (Fig. 3). The Müllerian duct however, does not show the character of an epithelial tube, but rather that of mesoepithelial cells. At both its rostral region and growing tip, the Müllerian duct does not express cytokeratin 8 (Fig. 3B and G) or E-cadherin (Fig. 3 D and I), but does show weak pan cytokeratin expression (Fig. 3C and H). At the growing tip, the Müllerian duct shows expression of vimentin and weaker expression in its rostral region (Fig. 3E and J). A higher magnification of vimentin staining of the Müllerian duct tip shows strong expression of vimentin by these cells (Fig. 3P). The expression of all four markers in the Müllerian duct, Wolffian duct and coelomic epithelium was identical in both males and females, indicating that the development of these tissues is independent of sex.

The Wolffian duct maintains its epithelial character in both sexes through E13.5 as can be seen by cytokeratin 8 (Fig. 4B, H and N), pan cytokeratin (Fig. 4C, I and O), E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4D, E, J, K, P and Q) and lack of vimentin expression (Fig. 4F, L and R). The coelomic epithelium retains expression of all four markers at this stage (Fig. 4). Cytokeratin 8 was not observed in the Müllerian duct by E13.5 (Fig. 4B, H and N) as well as E-cadherin in either sex (Fig. 4D, E, J, K, P and Q) and only very little pan cytokeratin was observed (Fig. 4C, I and O). However, the Müllerian duct does express epithelial cell markers later in gestation and this expression is maintained in the uterus of the adult (data not shown). Analysis at higher magnification reveals that in the most rostral region of the female Müllerian duct, the cells are beginning to express E-cadherin in their apical region suggesting the Müllerian duct is acquiring apical and basal polarity (Fig. 4S). This apical expression was not seen in the male Müllerian duct most likely due to the beginning of Müllerian duct regression (Fig. 4E). Vimentin expression in the Müllerian duct is weaker compared to that at E12.5, but still observed (Fig. 4 F, L and R). Of the three cell types analyzed, the Wolffian duct, the coelomic epithelium and the Müllerian duct, all three have a cellular character unlike the other two cell types and the Müllerian duct is most unique (Supplementary Table 2). The lack of all three epithelial markers and expression of a marker for mesenchyme suggests that the cells of the Müllerian duct are mesenchymal in character. However, the morphology of the cells implies otherwise (Fig. 3A, F, K and 4A, G, M). The cells immediately rostral of the growing tip show tight adhesion and have the shape of a cylinder. These cells are columnar and at various levels along the rostral duct, small lumens can be visualized, giving the Müllerian duct the morphological character of an epithelial tube. Thus, the forming Müllerian duct is mesoepithelial in character.

The Wolffian duct does not contribute cells to the Müllerian duct

To test the hypothesis that the Wolffian duct contributes cells to the growing Müllerian duct tip, we performed genetic fate mapping experiments using the R26R Cre reporter mouse strain (Soriano, 1999) and a transgenic mouse line that expresses Cre in the Wolffian duct (Yu et al., 2002). After Cre mediated recombination of the R26R locus, all cells expressing Cre and any daughter cells will express lacZ. Hoxb7-Cre is expressed along the entire length of the Wolffian duct at E11.5, 12.5 and 13.5 (Fig. 5A, C and E). At E11.5, just before Müllerian duct initiation, the entire length of the Wolffian duct of Hoxb7-Cre; R26R mice is positive for lacZ expression (Fig. 5A). This expression is consistent at E12.5, when the Müllerian duct has developed half the distance to the urogenital sinus (Fig. 5B, C, D, F) and at E13.5, corresponding to the completion of Müllerian duct formation (Fig. 5E). At E12.5, sections reveal that neither the rostral region of the Müllerian duct nor its growing tip, exhibits any lacZ expression (Fig. 5B and D). At E13.5 the entire length of the Müllerian duct is lacZ negative (Fig. 5E and data not shown). These results demonstrate that the Wolffian duct does not contribute cells to the developing Müllerian duct.

Fig. 5.

Wolffian duct specific Cre reporter analysis. lacZ staining of Hoxb7-Cre; R26R mice (A-F). The entire length of the Wolffian duct expresses lacZ from E11.5 to E13.5. Whole mount urogenital ridge at E11.5 (A), E12.5 (C) and E13.5 (E). Cross-section of the urogenital ridge at E12.5 (B, D, F). At both its growing tip and rostral of the growing tip, the Müllerian duct does not express lacZ (B, D). md, Müllerian duct; wd, Wolffian duct. Scale bar: 20 μM.

The Müllerian duct elongates by cell proliferation at the growing tip

The initial development of the Müllerian duct occurs by an invagination of cells from the coelomic epithelium, but the mechanism of its subsequent growth has remained controversial. We have demonstrated that the Wolffian duct does not contribute cells to the growing Müllerian duct. Before Müllerian duct elongation, the Wolffian duct is only separated from the coelomic epithelium by a basement membrane and the elongating Müllerian duct separates the two, suggesting the possibility that the coelomic epithelium contributes cells to the growing tip of the Müllerian duct. The coelomic epithelium has been shown to contribute cells to the Amhr2-expressing mesenchyme that surrounds the Müllerian duct (Zhan et al., 2006), it is therefore possible for the coelomic epithelium to also contribute cells to the developing Müllerian duct. To test this possibility, we developed a urogenital ridge recombinant explant culture assay using Lim1lz/+ and wild-type urogenital ridges. In this experiment, we collected both Lim1lz/+ and wild-type urogenital ridges at ∼E11.75 and cut them into two halves, a rostral half and a caudal half. This corresponds to the time of Müllerian duct initiation and invagination i.e. the Müllerian duct is located in the rostral half of the urogenital ridge. A rostral Lim1lz/+ ridge was then recombined with a caudal wild-type ridge and was subsequently cultured. We hypothesized that the entire length of the Müllerian duct is derived from the initial invagination of the coelomic epithelial wall, predicting that the Lim1lz/+ Müllerian duct would grow into the wild-type caudal ridge of the recombinant. Alternatively, if either the Wolffian duct or coelomic epithelium supplied cells to the elongating Müllerian duct at the level of the mesoepithelial tip, we would observe a wild-type Müllerian duct in the wild-type caudal ridge. Our results support the hypothesis that the Müllerian duct does not receive cells from either the Wolffian duct or coelomic epithelium, i.e. when a Lim1lz/+ rostral urogenital ridge was recombined with a wild-type caudal ridge, the lacZ positive Müllerian duct grew into the wild-type caudal ridge, n=4 (Fig. 6C, D, E and F).

Fig. 6.

Urogenital ridge recombinant explant culture and cell proliferation analysis. Whole mount urogenital ridge three days after culture and stained with X-gal (A, B, C, D). (A) Unmanipulated Lim1lz/+ control. (B) Negative recombinant in which both Müllerian ducts failed to grow into the wild-type caudal ridge. (C, D) Successful explant culture in which one (C) or both (D) Müllerian ducts grew past the point of manipulation into the wild-type caudal ridge. (E, F) Cross-section of successful recombinant explant culture. (E) Lim1lz/+ rostral ridge with both the Wolffian and Müllerian ducts expressing lacZ. (F) Wild-type caudal ridge with a Lim1lz/+ Müllerian duct, but wild-type, lacZ negative, Wolffian duct. (G-J) Cell proliferation analysis of the growing Müllerian duct tip at E12.5. Positive immunostaining for pH3 (G) and BrdU (H) in the rostral duct and pH3 (I) and BrdU (J) at the growing tip. E12.5 starting control for the Müllerian duct tip formation assay (K). The rostral Müllerian duct cells were removed from the proliferating tip cells and the ridge cultured. The isolated tip cells were able to form the Müllerian duct independent of the rostral duct cells (L). Arrowheads denote the point at which the Lim1lz/+ rostral ridge was cut. The light blue staining in the wild-type caudal ridges of B-D is background trapped in the tubules of the metanephric kidney. The line in K indicates the point at which the urogenital ridge was cut. g, gonad; k, kidney; md, Müllerian duct; wd, Wolffian duct. Scale bar: 20 μM.

This in vitro system is very sensitive and corroborates data showing that the Müllerian duct requires not only the presence of the Wolffian duct for its growth, but also close contact with it. If the Wolffian duct of the caudal ridge was not in contact with the Wolffian duct of the rostral ridge when recombined, the Müllerian duct would not grow past the point where the ridge had been cut (Fig. 6B and C). This result was the most common outcome with the Müllerian duct in >80% of the cultures ceasing its growth at the point of the cut, n=19. Furthermore, we noticed a bulge of cells at the point where the Müllerian duct did not continue its caudal growth (Fig. 6B and C). We therefore looked at markers for cell proliferation at the growing tip in wild-type embryos. It has previously been reported that the Müllerian duct is proliferative in the mouse and chick and the fraction of proliferating cells is small (Dyche, 1979; Jacob et al., 1999), however, no studies have examined the cells of the Müllerian duct tip. We performed BrdU labeling and immunohistochemistry as well as phospho-Histone H3 (pH3) immunohistochemistry, which are markers for DNA synthesis and mitosis, respectively. We find that cells of the Müllerian duct tip were positive for pH3 immuostaining (Fig. 6I) and also for BrdU (Fig. 6J) as well as cells of the rostral duct (Fig. 6 G and H). Proliferation by both the tip cells and the rostral cells leads to the question of which cells are important for the formation of the Müllerian duct? We hypothesize that the proliferating tip cells are necessary for the formation of the duct and that subsequent proliferation by the rostral cells provides for the increase in diameter and overall lengthening of the entire reproductive tract. To test this hypothesis we developed a novel in vitro Müllerian duct tip formation assay. Urogenital ridges were collected at E12.5 (Fig. 6K) and on one side of the ridge, the rostral Müllerian duct was removed from the ridge leaving only the tip cells in the caudal half. These ridges were then cultured and analyzed for the ability of the cells at the tip to form the rest of the duct. When the rostral cells of the Müllerian duct are removed from the proliferating tip cells, the proliferating tip cells are capable of forming the rest of the duct, n=3 (Fig. 6L). This assay does not conclusively confirm that the cells of the Müllerian duct tip are necessary for forming the duct, but it does demonstrate that the proliferating tip cells are sufficient for laying the foundation of the forming Müllerian duct.

Discussion

Timing Müllerian duct initiation to completion and its relation to genetic sex

To visualize the precise timing of Müllerian duct development we utilized the Lim1lz/+ allele (Kania et al., 2000). Lim1 is expressed in both the Wolffian duct epithelium and developing Müllerian duct (Kobayashi et al., 2004). Müllerian duct development has been described in the mouse as beginning at E11.5 and ending by E13.5 (Kaufman, 1999; Kobayashi et al., 2004). Using tail somite (TS) number as a precise indicator of developmental stage, we show that the Müllerian duct develops in a shorter window of time than what was previously described. Müllerian duct development first requires specification of cells from the coelomic epithelium to a Müllerian duct fate and the formation of a placode. Subsequently the Müllerian duct invaginates from the coelomic epithelium and then elongates caudally to the urogenital sinus (Gruenwald, 1941; Jacob et al., 1999). We show that specification of the coelomic epithelium occurs at TS19 (∼E11.75) as detected by lacZ staining of the Lim1lz/+ allele. The mechanism for how the cells of the coelomic epithelium are specified remains unclear, but is independent of the Wolffian duct and Wnt4 expression from the mesonephros (Carroll et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2004). By TS22, the Müllerian duct has completed the first phase of growth and contacted the Wolffian duct. In the second phase, the Müllerian duct extends caudally where it eventually connects to the urogenital sinus (Gruenwald, 1943). This second phase of development is dependent upon both the presence of and a signal from the Wolffian duct (Carroll et al., 2005; Gruenwald, 1941). The elongation of the Müllerian duct is complete by TS34 (∼E13.5) and it will either undergo regression in males or differentiation in females. In the mouse, somites are known to arise every 120 to 180 minutes (Gossler, 2002), therefore, development of the Müllerian duct from initiation to completion takes approximately 30 to 45 hours. Interestingly, the lengthening of the Müllerian duct occurs at almost twice the rate during the invagination phase than the elongation phase. This higher rate may be caused by both cell migration and proliferation during Müllerian duct invagination while the second phase only consists of cell proliferation.

After completion of its elongation to the urogenital sinus, Müllerian duct development is markedly different between sexes. Males will eliminate the Müllerian duct by expression of AMH (Jost, 1953). Females do not express AMH, which allows for the differentiation of the Müllerian duct into the female reproductive tract. Prior to this sexually dimorphic pattern, the development of the Müllerian duct is independent of the embryo's genetic sex. Dyche (1979) showed by both light and electron microscopic investigation that during the growing phase of development, the Müllerian duct was indistinguishable between sexes. In both sexes, the Müllerian duct undertook extensive remodeling and it was not until regression began that differences could be detected. Our studies corroborate these results as no morphological differences were observed in either sex from Müllerian duct initiation at TS19 to completion at TS34.

The character of the developing Müllerian duct

We examined the expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in the Wolffian and Müllerian ducts as well as the coelomic epithelium. Several studies have analyzed expression of different antigens in rat, mouse, golden hamster, human and chick. Dohr et al. (1987) described differential antigen expression between the Wolffian and Müllerian ducts in the rat, which led to their conclusion that the Wolffian duct did not contribute cells to the Müllerian duct. Prior to this, Paranko et al. (1986) studied the expression of cytokeratin and vimentin in the rat. Strong cytokeratin expression was observed in the Wolffian duct and not in the Müllerian duct while the Müllerian duct stained positively for vimentin. These findings corroborate those found in human (Magro and Grasso, 1995) and in chick (Jacob et al., 1999), but contradict those found in the golden hamster (Viebahn et al., 1987). Our data in the mouse confirm and extend the results in the rat, human and chick and show that the developing Müllerian duct is not an epithelial tube in nature, but is rather mesoepithelial in character. At the proliferating tip and even after completion of its formation, the Müllerian duct stains positive for the mesenchymal cell marker vimentin, but not for the epithelial cell markers cytokeratin 8 and E-cadherin. These mesoepithelial cells are responsible for the proliferation and formation of the Müllerian duct and once formation of the duct is complete, these cells then expand their regions of cell-cell contact, obtain a more cuboidal shape and acquire apicobasal polarity.

In the mouse, the epithelialization of the Müllerian duct occurs after E13.5 and is complete by birth. This would imply that male embryos do not develop a true Müllerian duct epithelium at the time when Müllerian duct regression begins shortly after E13.5. The mesoepithelial character of the Müllerian duct may facilitate its regression. AMH-induced regression is known to have a window of sensitivity and after this window of time the Müllerian duct is no longer susceptible to AMH-induced regression (Josso et al., 1976). This transient sensitivity occurs during the time that the Müllerian duct has not completed its epithelialization and once the Müllerian duct has become a true epithelial tube, it will no longer regress.

The role of the Wolffian duct in Müllerian duct development

It has previously been established that the Wolffian duct is necessary for the growth of the Müllerian duct (Carroll et al., 2005; Gruenwald, 1941; Kobayashi et al., 2005). Our results corroborate these findings and our recombinant explant experiments demonstrate the necessity of the Wolffian duct for Müllerian duct development. Furthermore, we show that this necessity is not dependent upon Wolffian duct cell contribution, but rather, the Wolffian duct provides an essential signal and guides the Müllerian duct to the urogenital sinus.

To our knowledge, the Müllerian duct is the only developing tubule that requires the presence of an epithelial tube for its development. However, the development of the zebrafish posterior lateral line system (PLL) occurs through a similar process. Primordial cells, originating from cephalic placodes migrate, proliferate and deposit neuoromast cells along a specified path. These primordial cells express a receptor, CXCR4, which binds to a ligand, stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1) expressed by a thin layer of cells along the horizontal myoseptum (Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere, 2004). Loss of either the ligand or receptor results in the inability of the primordial cells to migrate and thus, agenesis of the PLL. Interestingly, SDF1 is also expressed by the pronephros and when SDF1 is lost only in the horizontal myoseptum, the PLL diverts its path to follow the SDF1 expression along the pronephros (Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere, 2004).

An identified cellular mechanism for the elongating Müllerian duct

Similar to other forms of tubulogenesis, the Müllerian duct follows a simple mechanism for its development; cells proliferate. Here we provide evidence to suggest that it is the cells at the leading tip that are responsible for the formation of the Müllerian duct. However, the Müllerian duct is unique in that it follows a specific path in a rostral to caudal manner and requires the presence of the Wolffian duct for its development. The development of the Müllerian duct has been described as biphasic (Gruenwald, 1941), but here we propose three phases for the development of the Müllerian duct (Fig. 7). In the first phase, cells of the coelomic epithelium are specified to a Müllerian duct fate. This phase can be identified by a placode-like thickening of the coelomic epithelium (Jacob et al., 1999) and by the expression of Lim1 (Kobayashi et al., 2004)(Fig. 7A, B). This process is similar to that found in the development of the Drosophila tracheal system where cells of the surface ectoderm express the tracealess gene (Wilk et al., 1996). The exact mechanism, which specifies these cells, however, has not been determined. These specified and now Müllerian duct primordial cells then proceed to the second phase of growth. In the second phase, expression of Wnt4 by the mesonephros or coelomic epithelium causes these primordial cells to invaginate from the coelomic epithelium where they extend caudally to the Wolffian duct (Vainio et al., 1999)(Fig. 7C, D). Upon contact with the Wolffian duct, the third or elongation phase begins and it is in this phase that the Müllerian duct primordial cells proliferate and are dependent upon the Wolffian duct for development (Fig. 7E, F). This elongation requires the guidance of the Wolffian duct, as well as the necessary Wnt9b signal (Carroll et al., 2005; Gruenwald, 1941). Cells deposited by the proliferating primordium also proliferate to accommodate expansion of the duct (Dyche, 1979; Jacob et al., 1999). This expansion may be expansion of the overall diameter of the formed duct, lengthening, or both, but the amount of cell proliferation in the cells at the tip is more robust when compared to cells in the rostral region. Once the Müllerian duct has completed its elongation, the mesoepithelial cells will either begin regression in males or establish apical and basal polarities differentiating into an epithelial tubule and eventually the endometrial cell types of the female reproductive tract.

Fig. 7.

A three phase model for Müllerian duct development. In the first phase, cells of the coelomic epithelium are specified to become Müllerian duct cells (A, B). After specification the second phase begins and these cells invaginate caudally towards the Wolffian duct (C, D). Once the Müllerian duct comes into contact with the Wolffian duct, the third phase begins (E, F) and the Müllerian duct elongates caudally, following the path of the Wolffian duct, towards the urogenital sinus. Blue cells; mesoepithelial Müllerian duct cells, red cells; proliferating Müllerian duct precursor cells, brown cells; coelomic epithelial cells, yellow cells; Wolffian epithelial cells. ce; coelomic epithelium, md; Müllerian duct, wd, Wolffian duct

Supplementary Material

Summary of Müllerian duct measurements at TS22 and TS28 in micrometers. Both left and right Müllerian ducts were measured individually and the overall mean is the average of all ducts measured.

Summary of expression patterns in the Wolffian duct, Müllerian duct and coelomic epithelium for the antigens analyzed. + denotes expression of the antigen, ++ strong expression of the antigen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Akio Kobayashi for helpful comments of this manuscript. Hans-Martin Herz for German translations. Jennifer R. Molina and Erica Kreimann-Strobl for advice with E-cadherin immunofluorescence. We also thank Blanche Capel for initial discussions and technical advice with the urogenital ridge explant culture. These studies were supported by a fellowship from the Training Program in Molecular Genetics of Cancer from the National Cancer Institute CA009299 to G.D.O. and a grant from the National Institutes of Health HD30284 and an endowment from Ben F. Love to R.R.B. R.R.B. is a Senior Fellow of the M.D. Anderson Research Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note Added in Proof: While this manuscript was being reviewed Guioli et al. published results complementary to our study on the origin of the Müllerian duct in the chick and mouse. Dev Biol. 2007 Feb 15; 302(2), 389-98.

References

- Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP. Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell. 2005;9:283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas JF, S GC. Towards a cellular and molecular understanding of neurulation. Dev Dyn. 2001;221:117–145. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohr G, Tarmann T, Schiechl H. Different antigen expression on Wolffian and Mullerian cells in rat embryos as detected by monoclonal antibodies. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1987;176:239–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00310057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews U. Direct and mediated effects of testosterone: analysis of sex reversed mosaic mice heterozygous for testicular feminization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;80:68–74. doi: 10.1159/000014959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyche WJ. A comparative study of the differentiation and involution of the Mullerian duct and Wolffian duct in the male and female fetal mouse. J Morphol. 1979;162:175–209. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051620203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C. Development of the zebrafish lateral line. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossler A, T PPL. Somitogenesis: Segmentation of the Paraxial Mesoderm and the Delineation of Tissue Compartments. In: Rossant J, T PPL, editors. Mouse Development. Academic Press; 2002. pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenwald The Relation of the Growing Müllerian Duct to the Wolffian Duct and its Importance for the Genesis of Malformations. The Anatomical Record. 1941;81:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenwald Developmental Basis of Regenerative and Pathologic Growth in the Uterus. Archives of Pathology. 1943:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenwald P. Zur Entwicklungsmechanik des Urogenital systems beim Huhn. Arch f Entw-mechan. 1937;136:786–813. doi: 10.1007/BF00582219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker A, Capel B, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of Sry, the mouse sex determining gene. Development. 1995;121:1603–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL, Kolodziej PA. Organogenesis: molecular mechanisms of tubulogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:513–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob M, Christ B, Jacob HJ, Poelmann RE. The role of fibronectin and laminin in development and migration of the avian Wolffian duct with reference to somitogenesis. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1991;183:385–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00196840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob M, Konrad K, Jacob HJ. Early development of the mullerian duct in avian embryos with reference to the human. An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Cells Tissues Organs. 1999;164:63–81. doi: 10.1159/000016644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josso N, Picard JY, Trah D. The antimullerian hormone. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1976;33:117–67. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571133-3.50011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost A. Problems of fetal endocrinology. The gonadal and hypophyseal hormones. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1953;8:379–418. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-9825-5.50017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania A, Johnson RL, Jessell TM. Coordinate roles for LIM homeobox genes in directing the dorsoventral trajectory of motor axons in the vertebrate limb. Cell. 2000;102:161–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karavanova ID, Dove LF, Resau JH, Perantoni AO. Conditioned medium from a rat ureteric bud cell line in combination with bFGF induces complete differentiation of isolated metanephric mesenchyme. Development. 1996;122:4159–67. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MH, B JBL. The Anatomical Basis of Mouse Development. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Kwan KM, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP, Mendelsohn CL, Behringer RR. Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development. 2005;132:2809–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Shawlot W, Kania A, Behringer RR. Requirement of Lim1 for female reproductive tract development. Development. 2004;131:539–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.00951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubarsky B, Krasnow MA. Tube morphogenesis: making and shaping biological tubes. Cell. 2003;112:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro G, Grasso S. Expression of cytokeratins, vimentin and basement membrane components in human fetal male mullerian duct and perimullerian mesenchyme. Acta Histochem. 1995;97:13–8. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(11)80202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger RJ, K MA. Genetic control of branching morphogenesis. Science. 1999;284:1635–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5420.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina Y, Whitworth DJ, Racine C, Behringer RR. High specificity of Mullerian-inhibiting substance signaling in vivo. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2084–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.5.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N, Yoshida M, Kuratani S, Matsuo I, Aizawa S. Defects of urogenital development in mice lacking Emx2. Development. 1997;124:1653–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Getsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer RR. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien LE, Tang K, Kats ES, Schutz-Geschwender A, Lipschutz JH, Mostov KE. ERK and MMPs sequentially regulate distinct stages of epithelial tubule development. Dev Cell. 2004;7:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara-Ishihara T, Kuhlman J, Niswander L, Herzlinger D. The surface ectoderm is essential for nephric duct formation in intermediate mesoderm. Development. 1999;126:1103–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack AL, Runyan RB, Mostov KE. Morphogenetic mechanisms of epithelial tubulogenesis: MDCK cell polarity is transiently rearranged without loss of cell-cell contact during scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor-induced tubulogenesis. Dev Biol. 1998;204:64–79. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potemkina DA, Grebenshchikova VI, Korosteleva LI. Interaction of cells of Wolffian duct and mesothelium during initial growth period of Mullerian ducts in the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) Sov J Dev Biol. 1971;2:311–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M, Gomez-Pardo E, Dressler GR, Gruss P. Pax-2 controls multiple steps of urogenital development. Development. 1995;121:4057–65. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainio S, Heikkila M, Kispert A, Chin N, McMahon AP. Female development in mammals is regulated by Wnt-4 signalling. Nature. 1999;397:405–9. doi: 10.1038/17068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viebahn C, Lane EB, Ramaekers FC. The mesonephric (wolffian) and paramesonephric (mullerian) ducts of golden hamsters express different intermediate-filament proteins during development. Differentiation. 1987;34:175–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1987.tb00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk R, Weizman I, Shilo BZ. trachealess encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is an inducer of tracheal cell fates in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1996;10:93–102. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JR, B T. ‘Seamless’ endothelia in brain cepillaries during development of the rat's cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 1972;41:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the mouse metanephric kidney. Development. 2002;129:5301–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Fujino A, MacLaughlin DT, Manganaro TF, Szotek PP, Arango NA, Teixeira J, Donahoe PK. Mullerian inhibiting substance regulates its receptor/SMAD signaling and causes mesenchymal transition of the coelomic epithelial cells early in Mullerian duct regression. Development. 2006;133:2359–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.02383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of Müllerian duct measurements at TS22 and TS28 in micrometers. Both left and right Müllerian ducts were measured individually and the overall mean is the average of all ducts measured.

Summary of expression patterns in the Wolffian duct, Müllerian duct and coelomic epithelium for the antigens analyzed. + denotes expression of the antigen, ++ strong expression of the antigen.