Abstract

The development of high-affinity B cell memory is regulated through three separable phases, each involving antigen recognition by specific B cells and cognate T helper cells. Initially, antigen-primed B cells require cognate T cell help to gain entry into the germinal centre pathway to memory. Once in the germinal centre, B cells with variant B cell receptors must access antigens and present them to germinal centre T helper cells to enter long-lived memory B cell compartments. Following antigen recall, memory B cells require T cell help to proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells. A recent surge of information — resulting from dynamic B cell imaging in vivo and the elucidation of T follicular helper cell programmes — has reshaped the conceptual landscape surrounding the generation of memory B cells. In this Review, we integrate this new information about each phase of antigen-specific B cell development to describe the newly unravelled molecular dynamics of memory B cell programming.

Most effective vaccines that are in use today generate protective, antigen-specific B cell memory. To be effective, memory B cells must target the right antigen, express the appropriate antibody class and bind to their antigen with sufficiently high affinity to provide the host with long-term immune protection. These three cardinal attributes of antigen-specific B cell memory emerge progressively under the cognate guidance of T follicular helper cells (TFH cells) following initial priming and secondary challenge with antigen in vivo. Although we know a great deal about circulating antibodies, little is understood about the development of high-affinity memory B cells, which ultimately provide B cell-mediated immune protection in vivo.

Initial priming of naive B cells and subsequent cognate contact with TFH cells initiates immunoglobulin class switching and the differentiation of some B cells into plasma cells outside the germinal centre (GC); this is termed the pre-GC phase. This initial B cell–T cell contact is also required to induce the GC reaction, which drives the maturation of memory B cells. In the GC phase, cycles of B cell receptor (BCR) diversification and antigen-driven selection within the GC promote the development and subsequent export of high-affinity memory B cells. Effective B cell memory requires different functional classes of high-affinity plasma cells and an array of non-secreting memory B cells. The different classes of circulating antibodies engage separate antigen-clearance mechanisms, providing multiple serological barriers to re-infection. Similarly, non-secreting memory B cells can express affinity-matured BCRs of different classes (either IgM or downstream antibody isotypes following class switching). For example, IgG2a+ memory B cells express chemokine receptors that help them to traffic into inflamed tissues. IgA+ memory B cells are found at mucosal surfaces in the gut and lungs after local infections. In the memory phase, these class-specific memory B cells proliferate robustly in response to antigen re-exposure and promote the generation of high-affinity plasma cells under the control of cognate memory T helper cells. The exchange of information at each phase of antigen-specific engagement outlines the molecular dynamics of memory B cell programming.

In this Review, we evaluate recent findings on memory B cell programming and place them in their relevant developmental context in vivo. We consider the sequence of molecular exchanges between antigen-presenting cells and T helper cells at each stage, with emphasis on mouse models of adaptive immune responses; these sequences define major checkpoints in memory B cell maturation. The three main developmental phases of B cell memory are presented from the B cell perspective. In each phase, antigen recognition is followed by antigen presentation and cognate T cell help. These two-step processes each initiate and then consolidate a cellular reprogramming event that ultimately propels naive B cells into one of the multiple compartments of class-specific high-affinity memory B cells (FIG. 1).

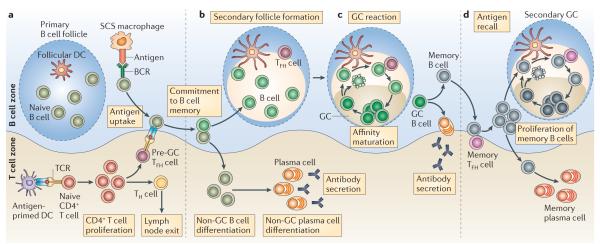

Figure 1. TFH cell-regulated memory B cell development.

a | Local protein vaccination induces dendritic cell (DC) maturation and migration to the T cell zones of draining lymph nodes. DCs that express peptide–MHC class II complexes engage naive, antigen-specific CD4+ T cells to induce their proliferation and differentiation into effector T helper (TH) cells. In the B cell zone, whole antigen is trapped by subcapsular sinus (SCS) macrophages and presented to naive follicular B cells. Antigen-specific B cells become activated, take up, process and present antigenic peptides and migrate towards the B cell–T cell borders of the draining lymph node. Effector TH cells emerge in multiple forms; emigrant TH cells exit the lymph node to function at distal tissue sites and T follicular helper (TFH) cells relocate to B cell–T cell borders and interfollicular regions. Cognate contact between pre-germinal centre (pre-GC) TFH cells and antigen-primed B cells is required for multiple programming events in the pathway to B cell memory. b | Clonal expansion, antibody class switching and non-GC plasma cell development proceeds in the extrafollicular regions of the lymph nodes. Secondary follicle formation and antibody class switching precede the initiation of the GC reaction, which forms the dominant pathway for the generation of memory B cells. c | Polarization of the secondary follicle anatomically signifies the initiation of the GC cycle. The dark zone supports GC centroblast proliferation, class-switch recombination and B cell receptor (BCR) diversification through somatic hypermutation. Non-cycling GC centrocytes move to the light zone and continually scan follicular DC networks. Centrocytes that lose the ability to bind to the presented antigen undergo apoptosis, while those that express a variant BCR with a higher affinity can compete for binding to antigen-specific GC TFH cells. Cognate contact with GC TFH cells requires peptide–MHC class II expression by the GC centrocytes. This contact can promote B cell re-entry into the dark zone and the GC cycle or exit from the GC and entry into the affinity-matured memory B cell compartments of non-secreting memory B cells and post-GC plasma cells. d | Following antigen re-challenge, memory B cells present antigens to memory TFH cells to promote memory B cell clonal expansion with rapid memory plasma cell generation and the induction of a secondary GC reaction. Although related to the cellular and molecular activities of the primary response, as depicted, the memory-response dynamics remain poorly resolved. TCR, T cell receptor.

Commitment to B cell memory

Priming naive B cells

B cells can acquire soluble antigens that freely diffuse into lymphoid follicles1 or that are transported through the lymphoid system of conduits2. Dynamic imaging has also captured early contact between naive B cells and dendritic cells (DCs)3. However, populations of lymph node subcapsular sinus macrophages (SCS macrophages) appear to be the most effective at presenting cell-associated antigens to follicular B cells4. B cells use complement receptors to take up non-cognate antigens presented by SCS macrophages, and they then transport these antigens into follicular regions and transfer them to follicular DCs, which can serve as a source of antigens for priming naive B cells4. By contrast, priming with the cognate antigen on first contact with SCS macrophages results in the movement of antigen-specific B cells to the B cell–T cell borders and induces antigen-specific B cell responses to captured antigens5–7. Hence, the SCS macrophages filtering the lymphatic fluid not only protect from systemic infection8, but also effectively initiate T helper cell-regulated antigen-specific B cell immunity.

Initial activation of naive B cells through the BCR triggers multiple gene expression programmes that enable effective contact with cognate T helper cells. Dynamic contact with membrane-associated antigens determines the amount of antigen that naive B cells accumulate following their first antigen exposure9. Effective cell contact requires the expression of the signalling adaptor DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis protein 8)10. Mutations in Dock8 disrupt the accumulation of integrin ligands in the immune synapse without altering BCR signalling events. B cell-specific conditional ablation of calcineurin regulatory subunit 1 (Cnb1)11, myocyte enhancer factor 2c (Mef2c)12,13, stromal interaction molecule 1 (Stim1) or Stim2 (REF. 14) has shown that calcium responsiveness is also necessary for cell cycle progression in these early stages. Hydrogen voltage-gated channel 1 (HVCN1), which is internalized with the BCR, has also been implicated in early B cell programming events15. B cells exposed to a short-duration BCR signal only partially activate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), but increase their expression of CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) and MHC class II molecules and their responsiveness to CD40 to promote more effective cognate T cell help16. Severe defects in early B cell proliferation have also implicated integrin binding by CD98 (REF. 17) and the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)18 in preparing the antigen-primed B cells to receive cognate T cell help in vivo. Hence, initial antigen recognition, uptake, processing and presentation have a crucial impact on the early developmental fate of B cells.

Early TFH cell programmes

TFH cells have emerged as a new class of T helper cells specialized to regulate B cell immune responses19,20. The central attribute of TFH cells is the capacity to secure contact with cognate antigen-primed B cells. Expression of CXC-chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5) and the loss of CCR7 expression positions antigen-primed TFH cells in follicular B cell regions of the lymph node. Recent studies showed that the transcription factor B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6) is expressed by antigen-specific TFH cells and that B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (BLIMP1; also known as PRDM1), which has an opposing function, is expressed by other T cells in the lymph node21. BCL-6 is required for the development of the TFH cell programme22–24, and its expression is reinforced in TFH cells following contact with pre-GC B cells25,26. Interleukin-21 (IL-21) also has a major role in TFH cell function, as a substantial loss of B cell immunity occurs in its absence. More recently, the transcription factors MAF and BATF were shown to act with BCL-6 to program TFH cell development27,28. Hence, the distinct transcriptional programming of unique cellular functions directs early TFH cell development, and this is central to subsequent memory B cell generation.

The TFH cell programme is one developmental option adopted by naive T helper cells following initial antigen-specific priming by DCs21. Expression of inducible T cell co-stimulator ligand (ICOSL) on DCs appears to be necessary to induce the TFH cell programme over more typical effector T helper cell options29. BCL-6 and BLIMP1 expression is mutually exclusive across these two T helper cell populations; this distinction is already evident by the second cell division in vivo and is associated with differential expression of IL-2 receptor subunit-α (IL-2Rα)29. Depending on the type of antigen, even B cells can be the priming cells for the TFH cell programme, as in the case of priming with particulate virus-like particles30. Dynamic imaging has placed initial contact between TFH cells and antigen-primed B cells within the follicular regions of lymphoid tissue31. The expression of the adaptor molecule SAP (SLAM-associated protein) can regulate B cell–TFH cell contact duration and affect antigen-specific B cell fate32. More recently, dynamic imaging has shown that crucial long-lasting interactions occur in the interfollicular zones of lymph nodes prior to GC formation33, and persistent BCL-6 expression in B cells was required to maintain this effective cognate contact31. Therefore, early TFH cell developmental programmes establish the capacity for cognate contact, which is needed to promote antigen-specific B cell commitment to antibody class and the subsequent maturation of BCR affinity (FIG. 2).

Figure 2. Pre-GC phase: commitment to memory.

a | Multiple subsets of antigen-specific pre-germinal centre (pre-GC) T follicular helper (TFH) cells are produced to regulate B cell immunity. So far, the organization of these subsets remains speculative; there is evidence for distinct TFH cell populations that secrete different cytokines and regulate commitment to separate antibody classes, as well as for other types of TFH cells that regulate non-GC plasma cell differentiation. Expression of B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6) and CXC-chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5) is thought to be a common feature of all TFH cell subsets. b | Antigen-primed B cells must process and present peptide–MHC class II complexes to receive cognate help from pre-GC TFH cells. Upregulation of the molecules involved in TFH cell contact is a poorly resolved component of early antigen-driven B cell maturation. Cognate contact between antigen-specific T cell receptors (TCRs) and peptide–MHC class II complexes focuses the intercellular exchange of molecular information between pre-GC B cells and TFH cells. The modifying interactions that occur at first contact are known to involve co-stimulatory molecule interactions (for example, CD40L–CD40 and inducible T cell co-stimulator (ICOS)–ICOSL), accessory molecule interactions (for example, SLAM family interactions and OX40–OX40L) and interactions between cytokines and their receptors (for example, interleukin-4 (IL-4)–IL-4R, interferon-γ (IFNγ)–IFNγR and IL-21–IL-21R). The distribution of these functional attributes in pre-GC TFH cell compartments is not yet well resolved in vivo. c | The non-GC pathway to plasma cell development permits antibody class-switch recombination without somatic hypermutation, and the outcome depends largely on the cytokine stimulus provided by pre-GC TFH cells. B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (BLIMP1) expression is required for plasma cell commitment across all antibody classes. The GC pathway to memory B cell development begins with extensive B cell proliferation in secondary follicles that polarize into dark and light zones to initiate the GC reaction. The GC pathway is associated with BCL-6 upregulation and AID expression to support both class-switch recombination and somatic hypermutation. These GC features enable the generation of all antibody classes and require a long duration of productive contact with pre-GC TFH cells. TH, T helper.

Initial cognate contact appears to imprint antibody class

Antibody class switching in antigen-primed B cells is an irreversible genetic recombination event. Briefly, sterile germline transcription through antibody switch regions provides activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID; also known as AICDA) with access to the single-stranded DNA template, enabling AID to deaminate cytosines34. This triggers the recruitment of DNA damage machinery that removes the resulting uracils and of mismatch repair factors that then generate double-strand breaks (DSBs). Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) completes the class-switch recombination (CSR) event. AID expression is largely restricted to antigen-activated B cells, although there is some evidence for low levels of AID in the bone marrow. Recent evidence indicates that, following antigen stimulation, AID expression is regulated in B cells by paired box protein 5 (PAX5), E-box proteins35, homeobox C4 (HOXC4)36 and fork-head box O1 (FOXO1)37. The adaptor protein 14-3-3 is recruited with AID to switch regions38, and polymerase-ζ has been implicated in the repair process associated with CSR39. Peripheral B cells undergoing CSR in the absence of the XRCC4 (X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 4) component of the DSB repair machinery are also highly susceptible to translocation events and oncogenic transformation40. Hence, antibody class switching is a destabilizing and potentially dangerous cellular event that is likely to be resolved early during the generation of antigen-specific memory B cells.

Cytokines and innate stimuli alone can drive naive IgM+ B cells to switch antibody class. However, typical vaccination responses require cognate T cell help to generate antigen-specific non-IgM antibodies. Early static imaging studies demonstrated coordinated antibody class switching in both the non-GC and GC pathways, suggesting that the earliest events of class switching are controlled at the pre-GC phase, following initial contact with TFH cells41. Early hybridoma studies further supported this notion with evidence that antibody class switching can occur without somatic hypermutation. Reporter mouse models have revealed that T cells produce cytokines at sites of antigen-specific contact with cognate B cells, and T cell-derived cytokines can be visualized in the follicular regions following initial T cell contact with B cells42–44. Different cytokines have been reported to drive commitment to different antibody classes. For example, IL-4 promotes IgG1 and IgE class switching45; interferon-γ (IFNγ) induces IgG2a45; and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) directs commitment to IgA46. In this manner, pre-GC B cell–TFH cell contact, involving the delivery of different cytokines, can imprint antibody class among the progeny of the antigen-responsive B cells. This commitment to antibody class appears to define an early and distinct developmental fate for antigen-primed B cells with functional consequences that remain poorly understood.

In antigen-responsive B cells, the molecular machinery that regulates CSR is deployed in an antibody class-specific manner. The global CSR machinery is targeted by transcription factors downstream of the cytokine receptors that control specific antibody classes. For example, IFNγ activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) downstream of the IFNγ receptor to induce T-bet and promote IgG2a class switching47,48. Similarly, TGFβ signals through the TGFβ receptor to activate SMAD and RUNX transcription factors that promote IgA class switching49. Furthermore, the transcriptional regulator BATF, which is required for TFH cell development, is also required in B cells to generate germ-line switch transcripts and to promote AID expression28. Finally, Ikaros regulates antibody class decisions by differentially controlling the transcriptional accessibility of constant region genes50. How the initial commitment to antibody class is maintained and propagated during clonal expansion, BCR diversification and affinity-based selection within the GC reaction remains an important but unresolved issue. However, it remains plausible that functional reprogramming accompanies CSR and creates separable lineages of class-specific memory B cells in vivo.

Cognate contact initiates GC formation

Initial pre-GC contact between B cells and antigen-specific TFH cells promotes a major division in the developing B cell response. Some antigen-primed B cells proceed towards plasma cell differentiation at this early stage. This early B cell fate occurs via an extrafollicular B cell pathway, and thus these B cells do not enter a GC reaction51. There is also recent evidence for an early memory B cell pathway that does not involve the GC reaction25,52. CSR proceeds in these non-GC pathways, supporting the notion of an early, pre-GC commitment to antibody class. The GC pathway to memory B cell development is the other developmental fate imprinted at this early stage of the B cell response, and this is the major focus of this Review.

Effective, antigen-specific contact between pre-GC B cells and TFH cells is required for the non-GC plasma cell pathway, although the short-duration B cell–TFH cell interactions that occur in the absence of SAP appear to be sufficient32. ERK signalling in B cells is needed to induce the transcriptional repressor BLIMP1 and plasma cell differentiation18. Regulation of the unfolded-protein response by X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) is not needed for plasma cell development but is necessary for antibody secretion53,54. Epstein–Barr virus-induced G protein-coupled receptor 2 (EBI2) also appears to be essential for B cell movement to extrafollicular sites and the non-GC plasma cell response55,56.

In addition, EBI2 guides recently activated B cells to interfollicular lymph node regions and then to outer follicular areas as a prelude to GC formation. Futhermore, there appears to be an early, pre-GC proliferative phase at the perimeter of follicles that also precedes GC formation and BCR diversification57. Interestingly, recent dynamic imaging studies indicate that TFH cells migrate to the follicle interior, even before the accumulation of GC B cells33.

It has been unclear how differential BCR affinity can affect the early fate of antigen-primed B cells. B cells of very low affinity are capable of forming GCs58 but fail to do so in the presence of high-affinity competition59. By contrast, there is evidence that the highest affinity B cells preferentially enter the non-GC plasma cell pathway, leaving lower affinity B cells to mature in the GC cycle60. This issue has been addressed more recently using intravital imaging to examine the early, pre-GC selection events61. In this model, access to antigens was not affected by BCR affinity, but the capacity of B cells to present antigens to pre-GC TFH cells was associated with BCR affinity. Increased T cell help promoted greater access to both the plasma cell pathway and the GC reaction. Thus, BCR affinity thresholds regulate B cell fate at the earliest pre-GC junctures of antigen-specific B cell–TFH cell interactions.

Effective priming by antigens initiates the pre-GC phase of memory B cell programming. Naive antigen-specific B cells must take up, process and present antigens to receive cognate help by antigen-specific TFH cells. These early TFH cell programmes drive commitment to antibody class, non-GC plasma cell differentiation and GC formation to influence crucial facets of adaptive B cell immunity and long-term B cell memory.

Affinity maturation

The GC cycle

GCs are dynamic microanatomical structures that arise in the follicular regions of secondary lymphoid tissues to support the generation of high-affinity B cell memory. As discussed, entry into the GC reaction is regulated by antigen-specific TFH cells20. GCs then promote antigen-specific clonal expansion and BCR diversification followed by positive selection of high-affinity BCR variants51. Within the GC, B cells scan antigens presented by follicular DCs and, following successful antigen binding, make contact with cognate GC TFH cells62. GCs must also delete ineffective BCR variants and guard against self-reactivity, a feature of the GC that remains poorly understood. Under the control of cognate GC TFH cells, B cells that express high-affinity BCR variants are exported from the GC to build multiple facets of antigen-specific B cell memory. In this manner, the GC cycle of activity regulates clonal composition and ultimately the long-term immune function of class-specific high-affinity memory B cells (FIG. 3).

Figure 3. The antigen-specific GC reaction.

The germinal centre (GC) cycle is initiated through the pre-GC contact of B cells with cognate T follicular helper (TFH) cells, as this promotes the extensive proliferation of antigen-primed B cells. The GC cycle is thought to begin when an IgD− secondary follicle polarizes to form two microanatomically distinct regions: the T cell zone-proximal dark zone (which contains proliferating centroblasts) and the T cell zone-distal light zone (which contains centrocytes, antigen-laden follicular dendritic cell (DC) networks and antigen-specific GC TFH cells). The clonal expansion of antigen-specific GC B cells in the dark zone is accompanied by B cell receptor (BCR) diversification through somatic hypermutation, which introduces point mutations into the variable-region segments of antibody genes. Antibody class-switch recombination can also proceed under these circumstances. Both somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination are associated with transcriptionally active gene loci, require DNA replication and repair machinery and occur during the cell cycle. Hence, these activities have been associated with the dark-zone phase of the GC cycle. Exit from the cell cycle coincides with the relocation of non-cycling GC B cells to the light zone. Continual scanning of follicular DCs that are coated with immune complexes is observed in the light zone and has been associated with the potential for GC B cells to test their variant BCRs for antigen-binding ability. Loss of antigen binding can lead to death by apoptosis and the clearance of dead cells by tingible body macrophages in the light zone. Positive signals through the BCR during the scanning of follicular DCs program GC B cells to compete for contact with cognate GC TFH cells. Productive contact with GC TFH cells can induce re-entry into the GC cycle; this involves movement back into the dark zone, the induction of the cell cycle and BCR re-diversification. Alternatively, affinity-matured GC B cells can exit the GC, either as non-secreting memory B cell precursors for the memory response, or as secreting long-lived memory plasma cells that contribute to serological memory.

Clonal expansion and BCR diversification

Early models report intense B cell clonal expansion in follicular regions that locally exclude naive B cells to form ‘secondary’ follicles63. Polarization of secondary follicles into ‘light’ zones that are rich in follicular DCs and GC TFH cells and ‘dark’ zones that contain many proliferating B cells provides an anatomical definition of an active GC microenvironment62. Although T cell-independent GC-like structures can emerge when there are increased numbers of B cell precursors, these structures are short-lived and do not support the diversification or positive selection of BCRs. Hence, the capacity for affinity maturation and memory B cell development can be considered as an integral functional component of a dynamic GC reaction in vivo (FIG. 4).

Figure 4. Memory B cell evolution.

a | Cues from pre-germinal centre (pre-GC) cognate T follicular helper (TFH) cells instruct antigen-primed B cells to initiate the GC reaction. It is likely that the commitment to antibody class is pre-programmed at this initial juncture and that all classes of B cells can seed the primary GC response. b | Molecular control of the cell cycle is an integral component of dark-zone B cell dynamics and involves the expression of B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6), although the ways in which BCL-6 contributes to this regulation remain poorly resolved. The expression and activity of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG) are required to initiate somatic hypermutation (SHM), which is targeted to single-stranded DNA. Following uracil excision, the DNA is processed by error-prone DNA polymerases to introduce point mutations into the variable regions of the rearranged antibody genes. Class-switch recombination (CSR) can also occur during this dark-zone phase using AID to target DNA cleavage to antibody switch regions; the DNA double strand breaks that are generated trigger the DNA damage machinery, which completes the CSR event. The associations between cell cycle control, SHM and CSR are not clearly resolved in vivo. c | To scan folicullar dendritic cells (DCs) for antigens, GC B cells continuously move along follicular DC processes that are laden with mature immune complexes. These interactions are more similar to stromal cell-associated trafficking behaviour than to stable immune synapse-like interactions. The affinity of the B cell receptor (BCR) for antigens may influence antigen uptake and peptide–MHC class II presentation at this juncture of development. Programmes of gene expression for molecules that are able to modify cognate contact may also be differentially induced as a result of BCR signal strength during follicular DC scanning. d | B cells then make contact for a longer duration with cognate GC TFH cells in the light zone, and this can be visualized directly in vivo. As in earlier, pre-GC events, these contacts must focus around T cell receptor (TCR)–peptide–MHC class II interactions and can be modified by a multitude of intercellular exchanges of molecular information. There is still little detailed analysis of these interactions in vivo. We depict the classes of molecules that can be associated with this crucial programming event, but the organization of these interactions and their precise developmental imprint are not yet clear. e | Antigen presentation by B cells can influence re-entry into the dark zone and the re-initiation of BCR diversification (which involves cell proliferation, SHM and CSR). f | GC cognate contact can also initiate B cell exit from the GC into the distinct non-secreting memory B cell and post-GC long-lived memory plasma cell compartments. BLIMP1, B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1; CR2, complement receptor 2; CXCR5, CXC-chemokine receptor 5; IFNγ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; TH, T helper.

The discovery of AID provided crucial insight into the molecular machinery that drives somatic hyper-mutation and BCR diversification64. Similarly to its function in CSR, AID is required for cytosine deamination to generate uracils that recruit the somatic hypermutation machinery. The initial changes target sequence-specific hotspots within the rearranged variable regions of antibody genes. Following uracil excision by uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG), the DNA is processed by error-prone DNA replication to introduce point mutations in the actively transcribed immunoglobulin locus. Error-prone processing using mismatch repair and base excision repair factors is selectively offset with high-fidelity processing to protect genome stability65. The range of sequences that are targeted by AID (as determined by the enzyme’s active site) can be altered to modify the somatic hypermutation of variable-region gene segments66 and the rate of antibody diversification67. AID stability in the cytoplasm of Ramos B cell lines can be regulated by heat shock protein 90 (HSP90); specific inhibition of HSP90 leads to destabilized AID68, and this provides a means to modify the rate of antibody diversification. The details of the mutating complex that contains AID, its action and its regulation in the GC reaction are active areas of research that have been reviewed in detail elsewhere64.

BCR diversification is dependent on DNA replication and is largely restricted to GC B cells in the pathway to memory. Earlier studies using dynamic imaging indicated that GC B cell proliferation occurs in both the light zone and the dark zone of the GC reaction69–71. There was also evidence for significant zonal movement and cellular exchange between these areas69,72. More recently, labelling of B cells based on their GC zonal location (using a photoactivatable green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag) provided more conclusive evidence for these activities in vivo73. These elegant studies indicated that proliferation was largely restricted to the dark zone and that this was followed by a net movement to the light zone. Importantly, movement back into the dark zone and re-initiation of proliferation was controlled by antigen presentation to GC TFH cells73. These studies provide experimental evidence that the reiterative cycles of BCR diversification and positive selection are central events during affinity maturation that drive clonal evolution in the antigen-specific memory B cell compartment.

Antigen scanning on follicular DCs

Affinity maturation refers to the rising affinity of antigen-specific antibodies that can be measured over time following infection or vaccination. Cell death is a prevalent outcome of the GC cycle51, and myeloid cell leukaemia sequence 1 (MCL1) has emerged as a major anti-apoptotic factor controlling GC B cell formation and survival16,74. Positive selection of variant GC B cells must be a major driving force in the GC and is based on the increased capacity of the mutated BCR to bind to its antigen. Direct imaging studies provided the first dynamic view of GC B cell and follicular DC interactions69–71. All groups reported a continuous scanning activity of GC B cells over follicular DC networks that were laden with immune complexes. These GC B cell movements were more reminiscent of stromal scanning activity than of cognate immune synapse pausing by T helper cells on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). These images show the stage at which variant GC B cells are most likely to contact antigens to test the binding properties of their mutated BCRs.

Cognate contact with GC TFH cells

After scanning follicular DCs, only a few GC B cells were shown to make stable, immune synapse-like contacts with GC TFH cells, as determined by two-photon imaging69. These early images gave rise to the notion that competition for GC TFH cells may be the limiting factor in GC B cell selection of variant high-affinity BCRs62. More recently, antigen presentation by GC B cells without BCR engagement was shown to dominate the selection mechanism in GCs73. GC B cells that were capable of presenting higher levels of antigen exited the GC reaction rapidly and produced more post-GC plasma cells than GC B cells that were less efficient at antigen presentation. These studies implicated similar mechanisms to those of the pre-GC selection event61 and argued strongly that antigen presentation to GC TFH cells is the rate-limiting event during affinity maturation in the GC cycle.

It remains technically difficult to manipulate cellular and molecular activities in the GC cycle without interfering with the developmental programmes that initiate the GC reaction in the first place. Many of the molecules associated with pre-GC TFH cell function may also function within the GC. BCL-6 expression itself is reinforced in TFH cells following contact with pre-GC B cells31. ICOS–ICOSL interactions are important throughout this pathway, at the early DC contact29 and pre-GC contact75 stages and probably during the GC reaction itself. IL-21 and its receptor appear to be of continued importance at the pre-GC stage and during the GC reaction25,26. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1P2) has an important role in confining GC B cells to the GC niche in vivo76. In addition, elevated expression levels of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) correlate with GC localization of the TFH cell compartment77, and the absence of PD1 ligand 2 on B cells affects plasma cell generation and affinity maturation78. Most interestingly, the association between cytokine production and class-specific GC B cells appears to continue in the GC long after the original CSR event43. This surprising functional pairing of GC TFH cells and class-switched GC B cells — for example, IL-4+ TFH cells with IgG1+ GC B cells and IFNγ+ TFH cells with IgG2a+ GC B cells — hints at the extended level of heterogeneity that exits in the GC cycle of memory B cell development. Hence, it is likely that each separable class-specific GC B cell compartment requires cognate contact with separate class-specific GC TFH cells.

Clonal evolution in the GC

Evidence connecting BCR signal strength in the GC B cell compartment and affinity maturation has been lacking. BCR signalling and antigen presentation are required to initiate the GC reaction and thus are difficult to manipulate specifically in the GC. Early GCs still develop in the absence of DOCK8, despite the defects in early immune synapse formation10. However, without DOCK8 these GCs do not persist and GC B cells do not undergo affinity maturation. Calcium influx as a consequence of BCR signalling also appears to be dispensable for affinity maturation under various T cell-dependent priming conditions in vivo. Although B cells deficient for the calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 or for CNB1 exhibit profound defects in proliferation in vitro14,11, these signalling molecules are dispensable for the maturation of antibody responses in vivo. Downstream of BCR signals, the transcription factor MEF2C is necessary for early B cell proliferation and GC formation12,13, but the pre-GC versus GC functions of MEF2C remain unresolved. B cell-specific deletion of nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic 1 (Nfatc1) also compromises B cell responses in vivo79, but the level of the defect remains unclear. Nevertheless, as BCR signal strength must drive affinity maturation at some level, it remains important to resolve the B cell-intrinsic mechanisms that help to shape the affinity of the memory B cell compartment.

B cell memory and antigen recall

B cell memory

The population of non-immunoglobulin-secreting cells that is produced in the GC reaction during a primary response largely comprises class-specific affinity-matured memory B cells. There are reports of early memory B cell development that does not occur in GCs25,52, although how well these germline BCR-expressing memory B cells compete with post-GC memory B cells in the antigen recall response remains to be evaluated. Affinity-matured IgM+ memory B cells can emerge from the GC reaction and persist for long periods in vivo80. These non-switched memory cells appear to be more active in secondary responses in the absence of circulating antibodies.

Genetic labelling of AID-expressing cells with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) has allowed memory B cells to be monitored over long periods81. Surprisingly, it was shown that primary-response GC reactions could persist for extended periods of time (over 8 months after priming) following immunization with certain types of antigen. In these studies, class-switched memory B cells rapidly promoted plasma cell generation, whereas their IgM+ counterparts promoted secondary GC reactions. Depending on the form of antigen delivery and the combination of innate stimuli provided with the antigen, B cell responses could be skewed towards memory formation with extended GC reactions, which can last over 1.5 years82. Hence, it is possible that persistent GCs can continuously produce non-secreting memory B cells well after the initial priming event.

High-affinity antibody-producing plasma cells that emerge from the GC reaction can also be considered an integral part of antigen-specific B cell memory. High-affinity GC B cells preferentially assort into the plasma cell compartment and produce high-affinity circulating antibodies83. In the lymph nodes, affinity-matured plasma cells dwell in paracortical areas to mature84 and then migrate towards the medullary regions before export85. CD93 is expressed at this early stage and is required for plasma cell survival in the bone marrow86. Clearly, the circulating antibodies that are produced by post-GC plasma cells contribute to ongoing serological immune protection87.

We have recently demonstrated that post-GC antibody-secreting B cells not only express BCRs, but also present antigens and can modulate cognate T helper cell responses88. These surprising studies further demonstrate that plasma cells negatively regulate the expression of BCL-6 and IL-21 in antigen-specific TFH cells88. Thus, plasma cells are not only the producers of antibodies; they can also engage in antigen-specific immune regulation. Signals through the BCR or MHC class II molecules on post-GC plasma cells may serve to regulate the ongoing production of high-affinity antibodies in the serum. The long-term antigen-presenting or regulatory function of post-GC plasma cells has not yet been elucidated.

Antigen persistence

Tonic signalling through the BCR and the downstream activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), together with signalling by B cell-activating factor (BAFF) through the BAFF receptor, are required for the survival of naive B cells in the periphery89,90. Similarly, inducible deletion of phospholipase Cγ2 (Plcg2) after the generation of antigen-specific memory B cells substantially depleted the memory B cell compartment and suggested a BCR signalling requirement for memory91. Nevertheless, earlier genetic studies indicated that cognate BCR specificity was not required to provide the tonic survival signal after the generation of memory B cells89. Thus, persistent antigen does not appear to be required for the survival of antigen-specific memory B cells, although memory B cell function has not been addressed in this model.

More recently, there has been evidence of persistent peptide–MHC class II complexes in the context of antiviral responses in vivo92, leading to local activation of naive T helper cells even after the clearance of the virus. We recently demonstrated a similar persistence of peptide–MHC class II complexes for longer than 100 days following vaccination with a protein antigen in a non-depot adjuvant93. The depots of peptide–MHC class II complexes were restricted to the lymph nodes that drained the initial vaccination site, and persistent antigen presentation induced naive T helper cell proliferation93. We proposed that peptide–MHC class II complexes on immunocompetent APCs had a role in confining the antigen-specific memory TFH cell compartment to lymph nodes that drained the site of initial priming20. Although it has been known for some time that follicular DC networks are capable of trapping whole antigens as immune complexes for extended periods of time62, the nature of the long-lived local APCs remains unresolved.

Recalling B cell memory

Antigen recall responses by memory B cells promote accelerated clonal expansion and rapid differentiation to high-affinity plasma cells. IgG1 BCRs show enhanced signal initiation and microclustering at the single-cell level compared with IgM BCRs owing to membrane-proximal regions in the cytoplasmic tails of IgG1 BCRs (REF. 94). The cytoplasmic tails of these BCRs in class-switched memory B cells can contribute substantially to the increased burst of clonal expansion that is associated with re-triggering by antigen95. There is evidence for distinct changes in BCR signalling pathways96–99. The increased affinity of the BCR on memory cells must also contribute to memory B cell sensitivity to low-dose soluble antigens that do not induce a primary immune response. In addition to these intrinsic attributes, circulating high-affinity antibodies contribute to the differential management of antigens in vivo. Rapid presentation of immune complexes to the memory B cells is enhanced. Furthermore, memory B cells require regulation by antigen-specific T helper cells to initiate secondary immune responses100. These issues have not been well studied but remain central to the capacity of memory B cell populations to expand and self-replenish and to boost the levels of high-affinity plasma cells and circulating antibodies that provide long-term immune protection (FIG. 5).

Figure 5. Memory response to antigen recall.

a | Memory B cell responses can emerge in the absence of innate inflammatory stimuli. In this case, the main antigen-presenting cells are the affinity-matured memory B cells themselves. b | The memory B cell response to T cell-dependent antigens still requires T helper (TH) cell-mediated regulation following antigen recall. When the priming and recall antigens are identical, memory TH cells are the rapid responders and are thought to emerge preferentially over their low-frequency naive counterparts. Regarding the regulation of memory B cell responses, antigen-specific memory T follicular helper (TFH) cells are the most likely candidates for rapid cognate regulation. c | Cognate contact at this developmental juncture occurs across sets of memory B cells and memory TFH cells, but the organization and kinetics of this process remain poorly resolved in vivo. There is rapid and vigorous local clonal expansion during the first 2–3 days after antigen exposure in both the memory B cell and memory TFH cell compartments. d | Proliferation of affinity-matured memory plasma cells occurs very quickly, and evidence suggests that most memory plasma cells have already undergone affinity maturation. e | There is evidence for memory B cell subsets that have a germinal centre (GC) phenotype and create GC-like structures following antigen recall. Whether these structures are residual from the primary-response GC or re-emerge with GC activities following recall has not been resolved. f | Increased numbers of memory B cells and memory-response plasma cells persist after antigen recall. It remains unclear whether these cells are the product of memory GC reactions or of the extrafollicular, non-GC memory response. DC, dendritic cell; TCR, T cell receptor.

There has been recent evidence that memory B cells can re-initiate a GC reaction following antigen recall. The type of antigen appears to have an impact on the persistence of the primary-response GC, with particulate antigens more likely to promote GC longevity81. Moreover, innate immune stimuli differentially affect persistent GC structures, with combinations of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR7 signals more effective than single stimuli82. Whether the secondary GC is a continuation and re-expansion of a primary GC remains unclear. More importantly, it remains to be determined whether these secondary or persistent GC-like structures support the re-diversification of affinity-matured BCRs and the selection of clonotypes with even higher affinities. These issues are central to the future management of prime–boost vaccination protocols and have substantial practical impact in this field.

Cognate contact with memory TFH cells

As discussed above, we have provided evidence for the local persistence of an antigen-specific memory TFH cell compartment. CXCR5+ TFH cells bind to peptide–MHC class II complexes with higher affinity, express lower levels of ICOS and have lost the capacity to express mRNAs encoding a range of cytokines, as compared with effector T helper cells21. These putative memory TFH cells rapidly upregulate cytokine signals following re-stimulation with a specific peptide in vivo. We propose that these locally confined memory TFH cells are the cognate regulators of the memory B cell response. Many of the antigen-specific memory TFH cells retain expression of CD69, which suggests recent contact with peptide–MHC class II complexes and provides a plausible mechanism for local retention. It is likely that memory B cells with high-affinity BCRs will rapidly capture very low levels of secondary antigen and present this antigen to the cognate memory TFH cells. Hence, memory B cells may be the primary APCs in the memory response, further accelerating the memory B cell response during recall.

Conclusions and perspectives

Effective high-affinity B cell memory remains the most desired outcome of most current vaccine strategies. Understanding the capacity of individual pathogens to penetrate the host is vital to this effort. Identifying the appropriate target specificity remains central to any effective vaccine formulation. However, unravelling the molecular details of memory B cell programming by antigen-specific T helper cells remains the major hurdle to the future rational design of subunit vaccines.

Beyond antigen recognition, antibody class determines immune function, and BCR affinity controls the sensitivity of memory B cells. Antigen contact initiates antigen presentation by B cells and a programme of developmental events, and this programme is consolidated following B cell contact with antigen-specific TFH cells. We have outlined these events as a progressive developmental programme across three related but distinct phases of antigen encounter. Dynamic imaging studies have revolutionized our perspective on these in vivo processes and have helped to redefine the central attributes of each developmental phase. Deciphering the programmes that control antigen-specific TFH cells has initiated our understanding of the molecular regulation of the cellular events that are crucial for long-term immune protection. We have started to appreciate the extent of cellular heterogeneity associated with molecular progression in B cell memory and have valuable new tools to measure the impact of experimental manipulation in vivo.

We remain cautious of manipulating crucial adaptive immune functions, but quietly optimistic. The molecular regulation of antigen-specific cellular events initiates a complex but finite set of regulatory programmes that can be modified both indirectly, following vaccination with innate stimuli, and perhaps directly, during the acquisition of high-affinity B cell memory. The vaccine boost is the most readily accessible phase of this strategy that can directly target antigen-specific adaptive responses. Unravelling the molecules and programmes that control each phase of memory B cell development provides a plethora of new targets for vaccine-based modification in vivo.

Glossary

- T follicular helper cells

(TFH cells). A distinct class of T helper cells specialized to regulate multiple stages of antigen-specific B cell immunity through cognate cell contact and the secretion of cytokines. There are three separable TFH cell subsets defined in the current literature that correspond to the three phases of memory B cell development. These are pre-GC TFH cells, GC TFH cells and memory TFH cells.

- Cognate contact

Contact between a B cell and a T follicular helper cell that recognizes the same antigen. This contact requires antigen-receptor engagement by cell-associated antigens or peptide–MHC complexes and can be modified by secondary interactions that can involve both cell-associated and secreted molecules. Cognate contact functions to initiate bidirectional developmental programming.

- Immunoglobulin class switching

A region-specific recombination process that occurs in antigen-activated B cells. It occurs between switch-region DNA sequences and results in a change in the class of antibody that is produced — from IgM to either IgG, IgA or IgE. This imparts flexibility to the humoral immune response and allows it to exploit the different capacities of these antibody classes to activate the appropriate downstream effector mechanisms.

- Plasma cells

Terminally differentiated, quiescent B cells that develop from plasmablasts and are characterized by the capacity to secrete large amounts of antibodies.

- Germinal centre

(GC). A lymphoid structure that arises within lymph node follicles after immunization with, or exposure to, a T cell-dependent antigen. The GC is specialized for facilitating the development of high-affinity, long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells.

- GC reaction

(Germinal centre reaction). A cycle of activity characterized by three stages. First, GC B cells undergo clonal expansion and B cell receptor diversification in the GC dark zone. The B cells then scan follicular dendritic cells for antigens, and finally make contact with cognate GC TFH cells in the GC light zone. Positive selection continues the GC cycle with re-entry into the dark zone or promotes exit from the GC into the memory B cell compartment.

- Class-specific memory B cells

Non-secreting memory B cells that express either IgM or downstream non-IgM antibody classes following T helper cell-regulated class-switch recombination.

- Subcapsular sinus macrophages

(SCS macrophages). A CD11b+CD169+ macrophage subset that populates the subcapsular sinus region of lymph nodes. These cells function to trap particulate antigens from the lymph and present antigens to follicular B cells.

- Follicular DCs

(Follicular dendritic cells). Specialized non-haematopoietic stromal cells that reside in the lymphoid follicles and germinal centres. These cells possess long dendrites and carry intact antigens on their surface. They are crucial for the optimal selection of B cells that produce antigen-binding antibodies.

- Activation-induced cytidine deaminase

(AID). An enzyme that is required for two crucial events in the germinal centre: somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination.

- Non-homologous end joining

(NHEJ). A mechanism for repairing double-strand DNA breaks that does not require homologous sequences for ligation. NHEJ is used to complete recombination during antibody class switching.

- Somatic hypermutation

A process in which point mutations are generated in the immunoglobulin variable-region gene segments of cycling centroblasts. Some mutations might generate a binding site with increased affinity for the specific antigen, but others can lead to loss of antigen recognition by the B cell receptor or the generation of a self-reactive B cell receptor.

- Unfolded-protein response

A response that increases the ability of the endoplasmic reticulum to fold and translocate proteins, decreases the synthesis of proteins, and can cause cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Pape KA, Catron DM, Itano AA, Jenkins MK. The humoral immune response is initiated in lymph nodes by B cells that acquire soluble antigen directly in the follicles. Immunity. 2007;26:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roozendaal R, et al. Conduits mediate transport of low-molecular-weight antigen to lymph node follicles. Immunity. 2009;30:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi H, Egen JG, Huang AY, Germain RN. Extrafollicular activation of lymph node B cells by antigen-bearing dendritic cells. Science. 2006;312:1672–1676. doi: 10.1126/science.1125703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batista FD, Harwood NE. The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:15–27. doi: 10.1038/nri2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrasco YR, Batista FD. B cells acquire particulate antigen in a macrophage-rich area at the boundary between the follicle and the subcapsular sinus of the lymph node. Immunity. 2007;27:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Junt T, et al. Subcapsular sinus macrophages in lymph nodes clear lymph-borne viruses and present them to antiviral B cells. Nature. 2007;450:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phan TG, Green JA, Gray EE, Xu Y, Cyster JG. Immune complex relay by subcapsular sinus macrophages and noncognate B cells drives antibody affinity maturation. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:786–793. doi: 10.1038/ni.1745. This study provides evidence that the initial non-cognate relay of antigens to follicular DC networks is required to support affinity maturation at later stages of the immune response.

- 8.Iannacone M, et al. Subcapsular sinus macrophages prevent CNS invasion on peripheral infection with a neurotropic virus. Nature. 2010;465:1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature09118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleire SJ, et al. B cell ligand discrimination through a spreading and contraction response. Science. 2006;312:738–741. doi: 10.1126/science.1123940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randall KL, Lambe T, Goodnow CC, Cornall RJ. The essential role of DOCK8 in humoral immunity. Dis. Markers. 2010;29:141–150. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winslow MM, Gallo EM, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR. The calcineurin phosphatase complex modulates immunogenic B cell responses. Immunity. 2006;24:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khiem D, Cyster JG, Schwarz JJ, Black BL. A p38 MAPK–MEF2C pathway regulates B-cell proliferation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17067–17072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804868105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilker PR, et al. Transcription factor Mef2c is required for B cell proliferation and survival after antigen receptor stimulation. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:603–612. doi: 10.1038/ni.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto M, et al. The calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 control B cell regulatory function through interleukin-10 production. Immunity. 2011;34:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capasso M, et al. HVCN1 modulates BCR signal strength via regulation of BCR-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:265–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damdinsuren B, et al. Single round of antigen receptor signaling programs naive B cells to receive T cell help. Immunity. 2010;32:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantor J, et al. CD98hc facilitates B cell proliferation and adaptive humoral immunity. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:412–419. doi: 10.1038/ni.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasuda T, et al. ERKs induce expression of the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 and subsequent plasma cell differentiation. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:ra25. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity. 2009;30:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fazilleau N, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Rosen H, McHeyzer-Williams MG. The function of follicular helper T cells is regulated by the strength of T cell antigen receptor binding. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:375–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston RJ, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nurieva RI, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu D, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linterman MA, et al. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zotos D, et al. IL-21 regulates germinal center B cell differentiation and proliferation through a B cell-intrinsic mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:365–378. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betz BC, et al. Batf coordinates multiple aspects of B and T cell function required for normal antibody responses. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:933–942. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ise W, et al. The transcription factor BATF controls the global regulators of class-switch recombination in both B cells and T cells. Nature Immunol. 2011;12:536–543. doi: 10.1038/ni.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi YS, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34:932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou B, et al. Selective utilization of Toll-like receptor and MyD88 signaling in B cells for enhancement of the antiviral germinal center response. Immunity. 2011;34:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitano M, et al. Bcl6 protein expression shapes pre-germinal center B cell dynamics and follicular helper T cell heterogeneity. Immunity. 2011;34:961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi H, Cannons JL, Klauschen F, Schwartzberg PL, Germain RN. SAP-controlled T–B cell interactions underlie germinal centre formation. Nature. 2008;455:764–769. doi: 10.1038/nature07345. An outstanding dynamic imaging study of pre-GC cognate contact between B cells and T cells that identified the functional impact of contact duration on antigen-specific B cell fate determination.

- 33.Kerfoot SM, et al. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity. 2011;34:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stavnezer J, Guikema JE, Schrader CE. Mechanism and regulation of class switch recombination. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:261–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tran TH, et al. B cell-specific and stimulation-responsive enhancers derepress Aicda by overcoming the effects of silencers. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:148–154. doi: 10.1038/ni.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park SR, et al. HoxC4 binds to the promoter of the cytidine deaminase AID gene to induce AID expression, class-switch DNA recombination and somatic hypermutation. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:540–550. doi: 10.1038/ni.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dengler HS, et al. Distinct functions for the transcription factor Foxo1 at various stages of B cell differentiation. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/ni.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z, et al. 14-3-3 adaptor proteins recruit AID to 5′-AGCT-3′-rich switch regions for class switch recombination. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1124–1135. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schenten D, et al. Polζ ablation in B cells impairs the germinal center reaction, class switch recombination, DNA break repair, and genome stability. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:477–490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JH, et al. Mechanisms promoting translocations in editing and switching peripheral B cells. Nature. 2009;460:231–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacob J, Kassir R, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. I. The architecture and dynamics of responding cell populations. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1165–1175. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King IL, Mohrs M. IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in reactive lymph nodes during helminth infection are T follicular helper cells. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1001–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zaretsky AG, et al. T follicular helper cells differentiate from Th2 cells in response to helminth antigens. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:991–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snapper CM, Paul WE. Interferon-γ and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cazac BB, Roes J. TGF-β receptor controls B cell responsiveness and induction of IgA in vivo. Immunity. 2000;13:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohr E, et al. IFN-γ produced by CD8 T cells induces T-bet-dependent and -independent class switching in B cells in responses to alum-precipitated protein vaccine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17292–17297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004879107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peng SL, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH. T-bet regulates IgG class switching and pathogenic autoantibody production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5545–5550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082114899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe K, et al. Requirement for Runx proteins in IgA class switching acting downstream of TGF-β1 and retinoic acid signaling. J. Immunol. 2010;184:2785–2792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sellars M, Reina-San-Martin B, Kastner P, Chan S. Ikaros controls isotype selection during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1073–1087. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toyama H, et al. Memory B cells without somatic hypermutation are generated from Bcl6-deficient B cells. Immunity. 2002;17:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00387-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu CC, Dougan SK, McGehee AM, Love JC, Ploegh HL. XBP-1 regulates signal transduction, transcription factors and bone marrow colonization in B cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:1624–1636. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Todd DJ, et al. XBP1 governs late events in plasma cell differentiation and is not required for antigen-specific memory B cell development. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:2151–2159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gatto D, Paus D, Basten A, Mackay CR, Brink R. Guidance of B cells by the orphan G protein-coupled receptor EBI2 shapes humoral immune responses. Immunity. 2009;31:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pereira JP, Kelly LM, Xu Y, Cyster JG. EBI2 mediates B cell segregation between the outer and centre follicle. Nature. 2009;460:1122–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature08226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coffey F, Alabyev B, Manser T. Initial clonal expansion of germinal center B cells takes place at the perimeter of follicles. Immunity. 2009;30:599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dal Porto JM, Haberman AM, Kelsoe G, Shlomchik MJ. Very low affinity B cells form germinal centers, become memory B cells, and participate in secondary immune responses when higher affinity competition is reduced. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1215–1221. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shih TA, Meffre E, Roederer M, Nussenzweig MC. Role of BCR affinity in T cell dependent antibody responses in vivo. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ni803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paus D, et al. Antigen recognition strength regulates the choice between extrafollicular plasma cell and germinal center B cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1081–1091. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwickert TA, et al. A dynamic T cell-limited checkpoint regulates affinity-dependent B cell entry into the germinal center. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1243–1252. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102477. This study addresses the early, pre-GC impact of BCR affinity on antigen access and initial priming, which permits cognate contact and regulates GC B cell fate.

- 62.Allen CD, Okada T, Cyster JG. Germinal-center organization and cellular dynamics. Immunity. 2007;27:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MacLennan IC. Germinal centers. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:117–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. Molecular mechanisms of antibody somatic hypermutation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061705.090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu M, et al. Two levels of protection for the B cell genome during somatic hypermutation. Nature. 2008;451:841–845. doi: 10.1038/nature06547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang M, Rada C, Neuberger MS. Altering the spectrum of immunoglobulin V gene somatic hypermutation by modifying the active site of AID. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:141–153. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang M, Yang Z, Rada C, Neuberger MS. AID upmutants isolated using a high-throughput screen highlight the immunity/cancer balance limiting DNA deaminase activity. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:769–776. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orthwein A, et al. Regulation of activation-induced deaminase stability and antibody gene diversification by Hsp90. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2751–2765. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Allen CD, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science. 2007;315:528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1136736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hauser AE, et al. Definition of germinal-center B cell migration in vivo reveals predominant intrazonal circulation patterns. Immunity. 2007;26:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwickert TA, et al. In vivo imaging of germinal centres reveals a dynamic open structure. Nature. 2007;446:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature05573. References 69–71 were seminal studies that used dynamic imaging to observe the movement of GC B cells along follicular DC networks in vivo. Importantly, these authors provided the first evidence of dynamic cognate contact between GC B cells and GC TFH cells in the light zones of active GCs in vivo.

- 72.Beltman JB, Allen CD, Cyster JG, de Boer RJ. B cells within germinal centers migrate preferentially from dark to light zone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8755–8760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101554108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Victora GD, et al. Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter. Cell. 2010;143:592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.032. A seminal study that provides experimental evidence in vivo for the role of antigen presentation by GC B cells in the selection of affinity-matured memory B cell compartments.

- 74.Vikstrom I, et al. Mcl-1 is essential for germinal center formation and B cell memory. Science. 2010;330:1095–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.1191793. This study made outstanding use of conditional gene ablation to discriminate between GC and post-GC regulation of antigen-specific B cell survival in vivo.

- 75.Vogelzang A, et al. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Green JA, et al. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1P2 maintains the homeostasis of germinal center B cells and promotes niche confinement. Nature Immunol. 2011;12:672–680. doi: 10.1038/ni.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haynes NM, et al. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5099–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Good-Jacobson KL, et al. PD-1 regulates germinal center B cell survival and the formation and affinity of long-lived plasma cells. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:535–542. doi: 10.1038/ni.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bhattacharyya S, et al. NFATc1 affects mouse splenic B cell function by controlling the calcineurin–NFAT signaling network. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:823–839. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dogan I, et al. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kasturi SP, et al. Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature. 2011;470:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Phan TG, et al. High affinity germinal center B cells are actively selected into the plasma cell compartment. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2419–2424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mohr E, et al. Dendritic cells and monocyte/macrophages that create the IL-6/APRIL-rich lymph node microenvironments where plasmablasts mature. J. Immunol. 2009;182:2113–2123. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fooksman DR, et al. Development and migration of plasma cells in the mouse lymph node. Immunity. 2010;33:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chevrier S, et al. CD93 is required for maintenance of antibody secretion and persistence of plasma cells in the bone marrow niche. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3895–3900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809736106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pelletier N, et al. Plasma cells negatively regulate the follicular helper T cell program. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:1110–1118. doi: 10.1038/ni.1954. This study provided the first evidence that plasma cells retain the capacity for antigen presentation and that this activity can dampen IL-21 and BCL-6 expression in TFH cells.

- 89.Maruyama M, Lam KP, Rajewsky K. Memory B-cell persistence is independent of persisting immunizing antigen. Nature. 2000;407:636–642. doi: 10.1038/35036600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Srinivasan L, et al. PI3 kinase signals BCR-dependent mature B cell survival. Cell. 2009;139:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hikida M, et al. PLC-γ2 is essential for formation and maintenance of memory B cells. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:681–689. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jelley-Gibbs DM, et al. Persistent depots of influenza antigen fail to induce a cytotoxic CD8 T cell response. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7563–7570. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fazilleau N, et al. Lymphoid reservoirs of antigen-specific memory T helper cells. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:753–761. doi: 10.1038/ni1472. This study showed that antigen-specific memory TFH cells remain largely resident in the lymph nodes in which they developed and provided evidence for persistent local antigen presentation.

- 94.Liu W, Meckel T, Tolar P, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. Intrinsic properties of immunoglobulin IgG1 isotype-switched B cell receptors promote microclustering and the initiation of signaling. Immunity. 2010;32:778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.006. This high resolution imaging study highlights the impact of class-switched BCRs on the dynamics of BCR oligomerization and microclustering. These changes may intrinsically contribute to enhanced memory B cell responsiveness in vivo.

- 95.Martin SW, Goodnow CC. Burst-enhancing role of the IgG membrane tail as a molecular determinant of memory. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:182–188. doi: 10.1038/ni752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Engels N, et al. Recruitment of the cytoplasmic adaptor Grb2 to surface IgG and IgE provides antigen receptor-intrinsic costimulation to class-switched B cells. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:1018–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Horikawa K, et al. Enhancement and suppression of signaling by the conserved tail of IgG memory-type B cell antigen receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:759–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Waisman A, et al. IgG1 B cell receptor signaling is inhibited by CD22 and promotes the development of B cells whose survival is less dependent on Igα/β. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:747–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wakabayashi C, Adachi T, Wienands J, Tsubata T. A distinct signaling pathway used by the IgG-containing B cell antigen receptor. Science. 2002;298:2392–2395. doi: 10.1126/science.1076963. References 98 and 99 highlight the enhanced signalling properties of class-switched BCRs, by showing that these BCRs can block the inhibitory action of CD22. Many molecular events may enhance memory B cell function to antigen recall in vivo.

- 100.Aiba Y, et al. Preferential localization of IgG memory B cells adjacent to contracted germinal centers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12192–12197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]