Abstract

Chemical probes are critical tools for elucidating the biological functions of proteins and can lead to new medicines for treating disease. The pharmacological validation of protein function requires verification that chemical probes engage their intended targets in vivo. Here we discuss technologies, both established and emergent, for measuring target engagement in living systems and propose that determining this parameter should become standard practice for chemical probe and drug discovery programs.

Determining the biological functions of proteins requires selective tools to perturb their expression and/or activity in living systems. Molecular biology methods, such as targeted gene disruption and RNA interference, are ubiquitous and fairly straightforward methods to achieve this goal. Small-molecule probes offer complementary and, in some ways, superior tools for interrogating proteins and pathways because they can provide greater spatiotemporal control over protein function and can perturb this parameter without concomitant changes in protein expression1. This latter feature, of course, also means that the effect of small-molecules on protein function can rarely be inferred from simple protein abundance measurements like Western blotting. Alternative assays must be enlisted to confirm that a small molecule interacts with its intended protein target in a living system, a parameter that is referred to as target engagement.

Why is measuring target engagement important? Researchers in the pharmaceutical industry and academic medicine have long recognized the value of proximal biomarkers that can faithfully report on drug-target interactions in preclinical and clinical settings2-5. Biomarkers enable a direct correlation between target engagement and measurements of drug efficacy and/or toxicity. If, for instance, full target occupancy is confirmed for a drug in vivo and the drug fails to produce an expected therapeutic effect, then the target and mechanism were properly tested and invalidated for the intended clinical indication. Absent measurements of target engagement, however, it can be very difficult to discern the basis for a drug's lack of efficacy6. Was the target invalid or did the drug fail to fully engage the target in vivo? An ideal assay would also measure: 1) the extent of target engagement, which can help to determine drug doses that produce efficacy at fractional target occupancy, while limiting side effects that might be caused by complete target occupancy; and 2) the potential for drug interactions with off-target proteins, such that efficacy and toxicity can be correlated with drug selectivity in vivo.

Measuring target engagement is not only critical for drug development, but also for chemical probes used in basic research. Indeed, the appetite for chemical probes has never been greater within the biology research community, in large part due to tremendous advances in organic synthesis and screening technologies7,8. Without methods to confirm that chemical probes directly and selectively engage their protein targets in living systems, however, it is difficult to attribute pharmacological effects to perturbation of the protein(s) of interest versus other mechanisms. Furthermore, one could argue that target engagement should be independently established for each biological system to which a chemical probe is applied, given that different cell types and model organisms may show varied probe uptake and metabolism, as well as distinct target expression levels and distribution.

Confirming target engagement for chemical probes may appear, on the surface, to be a simple task, but it can prove quite challenging, especially for proteins of poorly understood function or proteins that lack unique and easily assayed biochemical activities. These problems must, however, be experimentally addressed, as the alternative outcome – adoption of chemical probes that lack evidence of target engagement – has the potential to lead to a proliferation of pharmacological reagents of dubious mechanism. Here, we will discuss technologies, both established and emergent, for measuring target engagement in cells, model organisms, and human subjects. While the described technologies have their own respective strengths and limitations, in aggregate, we believe that they provide a generalizable approach to address target engagement at each stage of basic and clinical research. The continued maturation and broader implementation of target engagement technologies has the potential to create a future where each new chemical probe and drug candidate is paired with a robust assay that connects pharmacological effects to mechanism of action.

Target engagement in cellular systems

Chemical probes are often first evaluated for pharmacological activity in cell culture models, where much can be learned about the functions of proteins and pathways. Here, we will discuss methods for measuring target engagement in cells, placing special emphasis on emerging chemoproteomic approaches that evaluate compounds against numerous proteins in parallel to provide simultaneous readouts of on-target and off-target activity. We will also highlight instances where measurements of target engagement in cells have provided surprising results that differ from in vitro biochemical assays.

Established methods

For chemical probes that target enzymes, the most straightforward target engagement assay is arguably measurement of substrate and product changes. Substrate-product assays can, however, become problematic in cases where the measured biomolecules are not uniquely modified by the target enzyme of interest. Members of large enzyme families like kinases, proteases, and methyltransferases can share substrates, which means that substrate-product changes caused by a chemical probe cannot always be confidently assigned to a single enzyme.

Moving beyond enzymes, establishing target engagement for other protein classes often requires more direct measurements of probe-protein interactions. Radioligand-displacement assays can be used to confirm ligand binding to receptors in cells9. This approach can also be adapted to create photoactivatable radioligands to covalently label proteins10. Competition with a non-radioactive chemical probe can then occur in living cells and target engagement measured ex situ by, for instance, SDS-PAGE-radiography11. These assays depend on having a selective radioligand for the protein of interest, which may not be available for less well-characterized targets, and identification of probe-labeled targets (and off-targets) is difficult without a means to affinity enrich photolabeled proteins.

Emergent methods

Recently, several chemoproteomic methods have been introduced to measure target engagement in cells. Kinases are a major focal point of basic and drug discovery research12, but the massive size of this enzyme class, and its importance in many crosstalking signal transduction pathways, presents a problem for developing assays that can definitively report on individual probe-kinase interactions in cells. Downstream phosphorylated substrates can, for instance, be shared by several kinases, which reduces their value as activity readouts for individual kinases13. Recognizing that autophosphorylation constitutes a unambiguous readout of kinase activity, Paweletz et al. described a quantitative proteomic strategy to discover autophosphorylation events that serve as robust target engagement biomarkers for kinase inhibitors13 (Fig. 1a). Of the 12 autophosphorylation sites identified on the serine/threonine kinase PDK1, three events were found to be sensitive to PDK1 inhibitors. This work describes a potentially general method to discover proximal (auto)-phosphorylation biomarkers of kinase inhibition in cells.

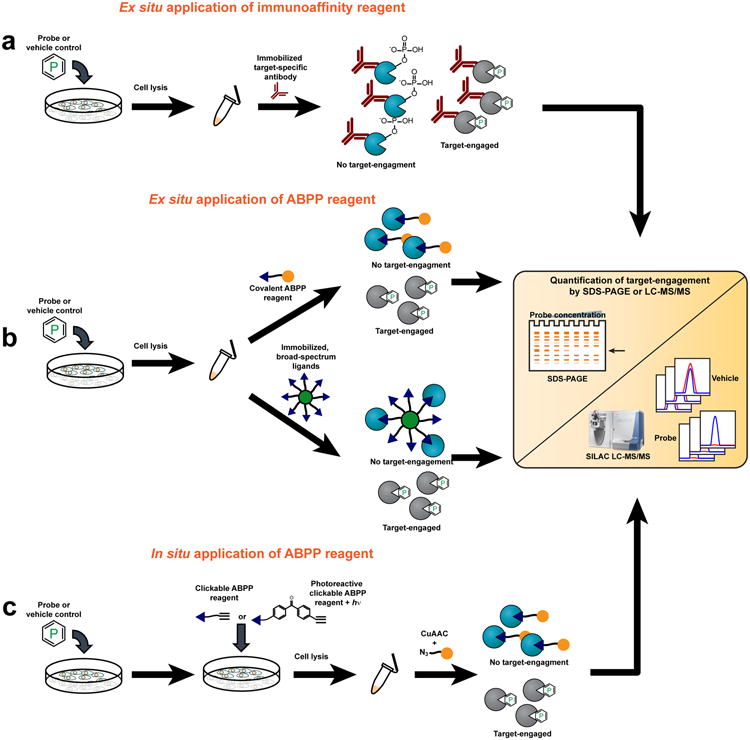

Figure 1. Approaches for measuring target engagement in cellular systems.

(a) Blockade of autophosphorylation as a proximal biomarker for kinase inhibition. Target engagement can be measured by immunoprecipitation of the kinase of interest from cells treated with a chemical probe (or vehicle control), followed by SILAC-LC-MS/MS to quantify changes in the phosphorylation status of autophosphorylated residues. (b) Ex situ evaluation of target engagement can be accomplished using two different approaches. In the upper pathway, an ABPP reagent is added to cell lysates following in situ treatment with a chemical probe (or vehicle control). The ABPP reagent is coupled to a reporter group (orange ball): either a fluorophore for target detection by SDS-PAGE coupled with in-gel fluorescence scanning or biotin for affinity-enrichment and target identification and quantification by LC-MS/MS. In the lower pathway, proteomes are incubated with bead-immobilized, broad-spectrum chemical ligands that affinity-enrich active (but not probe-engaged) enzymes. Target engagement is then monitored by observing loss-of-signal by LC-MS/MS. (c) Cell-permeant ABPP reagents can be generated by replacing reporter groups with latent affinity handles, such as an alkyne. If the ABPP reagent interacts with targets in a non-covalent manner, groups conferring photoreactivity (for example benzophenones or diazirines) can also be affixed. Following sequential treatment of cells with a chemical probe (or vehicle-control) and a cell-permeable ABPP reagent, cell lysis, and proteome preparation, a reporter group (orange ball) is covalently attached via a bioorthogonal reaction like CuAAC (click) chemistry and target engagement monitored by SDS-PAGE or LC-MS/MS.

Complementary chemoproteomic platforms have also been introduced to directly measure inhibitor-kinase interactions in cells. These assays involve treating cells with inhibitors followed by cell lysis and broad profiling of kinase activities in native proteomes (ex situ). Bantscheff et al. incubated proteomes from inhibitor- and vehicle-treated cells with bead-immobilized, broad-spectrum kinase inhibitors (kinobeads) and then bound kinases were analyzed and quantified by LC-MS14 (Fig. 1b). Numerous in vitro kinase-inhibitor interactions were verified in cells with this platform, and, interestingly, in some cases, kinase inhibition was only observed in living cells. The authors suggested that these examples may reflect kinases that exist in multiple conformational states in cells, only a subset of which interact with inhibitors. If these inhibitor-sensitive states are regulated by dynamic processes like protein phosphorylation, they may be inaccessible to recombinant kinases in vitro. Application of broad-spectrum activity-based protein profiling (ABPP15,16) reagents to assess small-molecule interactions for hundreds of kinases in parallel (termed the KiNativ platform17) is a complementary method for measuring target engagement (Fig. 1b). As was observed in studies with kinobeads, KiNativ analyses revealed that some inhibitors show dramatic differences in their activity against native versus recombinant kinases17, underscoring that target engagement in cells cannot be assumed, even for inhibitors that show good potency in vitro.

Importantly, both the kinobead and KiNativ technologies evaluate inhibitors against many kinases in parallel. As a result, unanticipated off-targets can be detected and surprising network-wide effects of kinase inhibitors can be discovered. For instance, Raf kinase inhibitors produce the expected reductions in B-Raf activity in cells, but paradoxically caused increases in A-Raf17.

We anticipate that additional platforms for measuring kinase activity in native proteomes, including new LC-MS18 and fluorescence19 substrate methods, should also prove adaptable for target engagement assays in cells. Finally, the aforementioned chemoproteomic methods can be extended to other enzyme classes20 for the ex situ analysis of target engagement by inhibitors.

In each of the aforementioned assay formats, care must taken to ensure that probe-protein interactions are not compromised during the cell lysis step. This is less problematic for chemical probes that act by a covalent mechanism, since their degree of target engagement is effectively frozen at the stage of cell lysis and stable to subsequent sample processing steps. We and others have shown that covalent ligands can be appended to reporter tags, such as fluorophores, biotin, and latent affinity handles like alkynes and azides, to create both broad-spectrum17,21,22 and tailored23-27 ABPP reagents that can be used to measure target engagement in living cells (Fig 1c). ABPP reagents can either be added to untreated cells/proteomes to identify reactive proteins or used in a competitive mode to identify proteins whose ABPP signals are blocked by a pre-treatment of cells with an unlabeled chemical probe (Fig. 1b and c). There are instances where appending a biotin or fluorophore tag to a covalent probe is compatible with in situ analysis; bulky reporter groups, however, can also impair the cell permeability and protein interactions of probes. These issues can largely be circumvented by using alkynes or azides, which impose a minimal steric footprint on the parent probe and can be coupled to reporter tags by biologically inert (“bioorthogonal”) reactions like copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC)28 and/or Staudinger ligation29 to provide a sensitive and robust method to assess target engagement by direct or competitive ABPP.

Ideally, the chemoproteomic mapping of on-target (and off-target) interactions for chemical probes would be accomplished directly in living cells (in situ) without requiring a post-lysis step. This goal is relatively simple to accomplish for covalent probes using competitive ABPP30 and can also be extended to probes that bind reversibly to protein targets by creating analogues that possess: 1) a photoreactive group for UV light-induced trapping of probe-protein interactions in cells, and 2) a latent affinity handle for target detection, enrichment and identification31 (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, competitive ABPP has identified probe-protein interactions that occur selectively in cells32, but not cell lysates, once again emphasizing the value of measuring target engagement in living systems. Competitive ABPP has also helped to refine our understanding of the selectivity of inhibitors in cells. The HDAC inhibitor SAHA, for instance, was originally considered to be a pan inhibitor for all eleven class I and II HDACs. Competitive ABPP methods, however, only identified four HDACs that were strongly bound to SAHA in cells – HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 632. More sophisticated substrate assays for HDACs have verified this selectivity profile for SAHA33.

Target engagement in model organisms

Once the cellular activity of chemical probes has been investigated, the next step in their characterization typically involves animal models, where the function of protein targets can be evaluated in a more physiologically relevant context. Measuring target engagement in vivo can, somewhat paradoxically, prove more straightforward for some proteins, if, for instance, their unique biochemical activities are only revealed in the context of an intact organism. But, model organisms also present serious technical challenges for evaluating target engagement, as they are only amenable to a subset of the chemoproteomic methods accommodated by cellular systems.

Established methods

Target engagement for chemical probes that inhibit enzymes can sometimes be evaluated in animal models using specific substrate and/or product biomarkers. In certain cases, the substrate and enzyme originate from different tissues3 and, therefore, establishing their relationship would not have been straightforward using simpler cell models. Conversely, substrates that accurately report on enzyme inhibition in cells may lose their specificity in animal models, where they are exposed to many other enzymes. Such complexities emphasize the importance of advanced metabolomics and proteomic methods34,35 that are enabling researchers, for the first time, to broadly search for enzyme substrates directly in animal models.

Radioligand-displacement assays can also measure target engagement in animal models and extended to non-enzymatic targets such as receptors2. These assays typically involve pre-treatment of rodents with a dose-range of chemical probe followed by a radiolabeled tracer ligand (radiotracer) that also binds to the target protein and then measurement of the radiotracer in the organ of interest. Dose-dependent reduction in radiotracer signal can be used to calculate target engagement. Radioligand-displacement assays, however, require rather intricate controls to account for background (unbound) radiotracer and are therefore most suitable for abundant proteins or proteins that display restricted anatomical distributions (which affords control tissues for background subtraction). More recently, ligand-displacement assays have been introduced that use LC-MS to measure ligand content in tissues36. These assays have the advantages of multiplexing ligands and circumventing the need for radioligands, but still suffer from the aforementioned challenge of distinguishing specific binding from background.

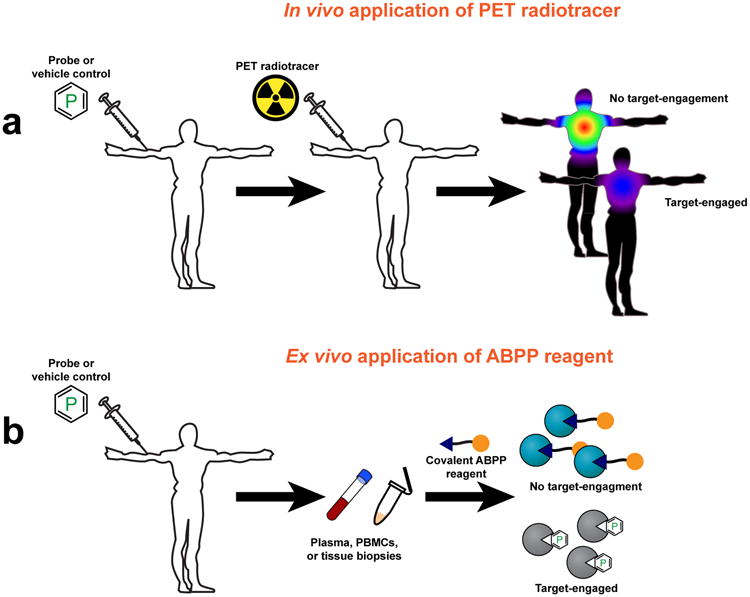

Advances in whole animal imaging have provided non-invasive formats for measuring target engagement. This can be accomplished using micro-PET (positron emission tomography)37 (Fig. 2a). While microPET is gaining utility as a target engagement assay, it still faces many challenges, including limited spatial resolution and a requirement for sophisticated and expensive chemistry and imaging facilities37.

Figure 2.

Approaches for measuring target engagement in model organisms. (a) Target engagement can be monitored in vivo with radiotracer-based imaging methods such as microPET. For these methods, animals are usually pre-treated with a chemical probe or vehicle followed by administration of the radiotracer. Engaged targets do not bind the radiotracer; thus, loss of PET-signal can be used to assess target engagement. (b) Target engagement can be monitored ex situ by adding an ABPP reagent to tissue-lysates harvested from animals dosed with a chemical probe (or vehicle control). Depending on the choice of reporter group (orange ball), target engagement can then be measured via SDS-PAGE or LC-MS/MS (Fig. 1). (c) For in vivo observation of target engagement, cell-permeant ABPP reagents can be generated that bear a latent affinity handle, such as an alkyne. After dosing animals with chemical probe (or vehicle control), the ABPP reagent is administered in vivo. Tissues of interest are then harvested and homogenized and targets visualized by conjugation to a reporter group (orange ball) by a bioorthogonal reaction like CuAAC (click) chemistry.

Emergent methods

Competitive ABPP has been applied in several instances to measure target engagement and selectivity for covalent inhibitors of enzymes in animal models38,39 (Fig. 2b). Covalent probes can also be modified to bear a bioorthogonal affinity handle (e.g., alkyne), which enables direct measurement of target (and off-target) engagement in vivo using click chemistry-ABPP methods39. Competitive ABPP can further be combined with non-invasive imaging to visualize target engagement in living animals. Bogyo and colleagues, for instance, have described quenched and non-quenched fluorescent ABPP reagents that react with subclasses of proteases in vivo 25,40,41. An advantage of these ABPP reagents over more traditional fluorescent substrates is that they can be used to couple in vivo measurements of protease activity to the identification of inhibited proteases using ex vivo chemoproteomic methods41.

Chemoproteomics can also be used to determine target engagement for reversible chemical probes in animal models. Choi et al. used the ex vivo KiNativ method to confirm in vivo-activity and selectivity for an inhibitor (HG-10-102-01) of the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2)42, which is mutated in a subset of patients with Parkinson's disease. Recently, we have shown that clickable, covalent ABPP reagents can be used to establish target engagement for reversible inhibitors in vivo43 (Fig. 2c). Mice were treated with reversible inhibitors of the serine hydrolases LYPLA1 or LYPLA2 followed by clickable ABPP reagents that react with these enzymes and several other serine hydrolases. Analysis of enzyme activity profiles from excised tissues revealed that the inhibitors blocked LYPLA1/2 activity with good selectivity in most tissues. This strategy has the advantage of directly evaluating target (and off-target) engagement in vivo, but also requires clickable ABPP probes that exhibit a tempered rate of reactivity with their enzyme targets, such that competition for binding by reversible inhibitors can be confidently measured.

Target engagement in humans

From a translational perspective, it is ultimately important to measure target engagement in humans. Indeed, there are many historical examples of drug candidates that showed promising activity in preclinical models, but failed to produce efficacy in humans, and, in cases where target engagement assays were lacking, it has been difficult to conclude whether poor clinical activity was due to the drug (i.e., the drug did not bind to its target in humans) or the target (i.e., the drug-target interaction did not produce the desired biological effect)6. Considerable effort has therefore been placed on developing target engagement assays that are compatible with human clinical studies. Several methods have been described for determining target engagement in humans that span from classical proximal substrate-product biomarkers to advanced in vivo imaging and ex vivo chemoproteomic analysis of human blood cells.

Established methods

For certain enzymes, target engagement can be determined in humans by measuring substrate or product changes in drawn blood, plasma, or blood cells. This is particularly relevant for enzymes with physiological functions that are directly tied to circulating levels of their substrates and products. Krishna et al. established target engagement for sitagliptin, an inhibitor of dipeptidylpeptidase-4 (DPP4), in humans by measuring elevated plasma levels for the DPP4-regulated hormone GLP-13. Importantly, maximal elevations in GLP-1 correlated with > 95% blockade of DPP4 enzyme activity (extrapolated from an ex vivo substrate assay) and peak acute glucose lowering efficacy in patients with type-2 diabetes. These data were critical for the ultimate approval of sitaglipitin as a first-in-class drug for treating type-2 diabetes.

Many protein targets perform tissue-restricted functions that cannot easily be measured in (or inferred from) blood samples. Measuring target engagement for these proteins has benefited from the development of non-invasive imaging methods, most notably, PET2,4,5 (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, PET experiments have identified drug candidates, such as the histamine H3-receptor antagonist GSK189254, that exhibit substantially more potent (> 10-fold) target engagement in humans than preclinical animal models44. PET has also enabled quantitative comparisons of fractional target occupancy with drug efficacy and side effects, which has proven crucial for establishing a therapeutic window for D2 dopamine receptor antagonists and partial agonists4,45. Finally, rigorous use of PET can help to terminate the progression of drug candidates that fail to exhibit efficacy in humans despite fully engaging their protein targets4,46. These findings underscore the importance of directly measuring target engagement in humans rather than inferring these values from animal models, where drugs may show different levels of target engagement and biological activity.

Figure 3.

Approaches for measuring target engagement in humans. (a) Target engagement can be monitored in humans by PET, wherein human subjects are usually pre-treated with probe or vehicle, followed by administration of the radiotracer. Engaged targets do not bind the radiotracer; thus, loss of PET-signal can be used to assess target engagement. (b) Target engagement in humans can be monitored ex situ by harvesting plasma, PBMCs, or tissue biopsies from subjects that have been treated with a chemical probe (or vehicle control). An ABPP reagent is then added and, depending on the choice of reporter group (orange ball), target engagement can be measured via fluorescent SDS-PAGE or LC-MS/MS (Fig. 1).

PET also presents many technical challenges, especially for novel protein targets, for which it can be difficult to identify radioligands that have suitable binding affinity and metabolism for target engagement assays. Also, the further that PET radioligands deviate in structure from the parent drug under investigation, the more likely they will fail to report on all of the proteins that interact with the drug. Potential off-target interactions for drugs thus become challenging to assess by PET.

Emergent methods

In the past few years, chemoproteomic methods have begun to impact the study of target engagement in humans (Fig. 3b). Bortezomib is a first-in-class proteasome inhibitor used for the treatment of multiple myeloma47. Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is a principal side effect of bortezomib. Arastu-Kapur et al. developed a second-generation proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib that exhibits reduced PN48. To establish a molecular basis for the different side-effect profiles of bortezamib and carfilzomib, scientists initially evaluated the off-target profiles for these drugs in isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by competitive ABPP 21, resulting in the identification of multiple serine proteases that were selectively inactivated by bortezomib, but not carfilzomib48. The cellular data were then substantiated in vivo by performing competitive ABPP on PBMCs taken from human subjects treated with proteasome inhibitors 48. These chemoproteomic findings suggest that cross-reactivity with serine proteases could contribute to the PN side effects of bortezamib.

Several covalent kinase inhibitors have entered clinical development, mostly for the treatment of cancer49. Some of these inhibitors have also been converted into ABPP probes for target engagement studies. Recently, Advani et al. reported phase I results for a covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor PCI-32765, which is under clinical investigation for treating B-cell malignancies50. The authors used a fluorescently tagged variant of PCI-3276551 in competitive ABPP assays to establish the dose of PCI-32675 required to produce full and sustained inhibition of BTK (measured in PBMCs from drug-treated human subjects). These chemoproteomic data were then used to select an appropriate dosing schedule for phase II studies.

Conclusion and future directions

Definitive assays for target engagement are fundamental to the science of chemical probe development and protein function assignment in that they help to determine a mechanism of action for small molecules in living systems, including cell and animal models, and humans. Absent this knowledge, chemical probes of uncertain or misassigned mechanism may be disseminated throughout the basic research community and even enter clinical development52, which can result in unexpected and contentious outcomes. Accordingly, we believe that direct measurements of target engagement should become standard practice in the development of new chemical probes, at least in cellular systems, where a rich complement of chemoproteomic methods can be brought into action. If a probe is intended for use in animal models, evidence of target engagement in vivo is desirable.

Of course, a universal target-engagement assay does not yet exist, and, given the diverse properties, functions, and biological distributions of proteins, tailored engagement assays will be needed to address different classes of probes and their targets. Nonetheless, general guidelines can inform future efforts to integrate target engagement methods into basic chemical biology research and drug development programs. First, proximal assays that report directly on probe-protein interactions are more valuable than distal readouts that can be affected by interceding pathways. Proximal assays can detect the specific substrates or products of an enzyme target or measure direct probe-target binding interactions. Second, target engagement assays that also monitor probe interactions against many other related proteins provide a valuable assessment of probe selectivity. Here, emerging chemoproteomic methods have an advantage over more classical assays that only measure probe interactions with a single protein target. Third, one cannot assume that a probe's target engagement and selectivity profiles will be preserved as the complexity of the experimental systems grows from in vitro to cells, to animals or to humans. For this reason, chemical biology programs that aspire to progress toward drug development should measure target engagement in cells, animal models and humans.

This Commentary has focused on emerging chemoproteomic methods for measuring target engagement, a bias rooted in our belief that these approaches have the potential to provide unprecedented levels of insight into the mechanisms of action for chemical probes. Chemoproteomic methods can determine the full spectrum of proteins that interact with a chemical probe in a wide range of living systems and not only confirm whether a probe engages its target with good selectivity, but also help to elucidate the mechanism of action for probes that produce their biological effects by interacting with multiple protein targets (“polypharmacology”53). Chemoproteomic approaches are necessarily invasive, which, while not problematic for cell or animal models, limits their application in human studies to accessible cell, fluid and tissue samples. Here, in vivo imaging has a clear advantage in that it is non-invasive, albeit without a means to easily assess probe interactions with the broader proteome. Thus chemoproteomic and imaging approaches are complementary strategies for measuring target engagement in vivo, and these approaches can even be combined54.

Implementing target engagement assays to inform on protein function and physiological processes still faces many challenges. How accurate, for instance, do target engagement assays need to be, especially in cases where the target itself may produce different biological effects when partially or fully engaged? Continued efforts to improve quantitative measurements of target engagement and their relation to the pharmacological effects of chemical probes in both preclinical and clinical settings should enhance our understanding of proteins that impact multiple physiological processes, as well as better define therapeutic windows for drugs that target these proteins. Another persistent problem is the development of robust target engagement assays for proteins that are of very low-abundance or only expressed in cells that are scarce. In these cases, the sensitivity of current target engagement assays is tested. While continued improvements in the detection and resolution limits of instruments should help, there is also room for disruptive technologies based on entirely new analytical platforms for measuring probe-protein interactions with maximal sensitivity in biological samples of limited quantity. It would also be wonderful to consider ways to transfer the full spectrum of chemoproteomic methods operational in cells to higher animal models. Most clickable, photoreactive ABPP reagents are, for instance, activated by UV light, which does not penetrate mammals. Could technologies emerge that enable spatially and temporally regulated chemical crosslinking of probes to protein targets in vivo? Finally, from a biological perspective, what happens when sustained target engagement leads to loss of drug efficacy. Interpreting how target engagement relates to drug tolerance and resistance, or paradoxical instances of drug resistance being coupled to drug dependence55 is a fertile field for future investigation and could benefit from additional technologies that examine these intriguing phenomena using complementary global profiling methods56,57.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the National Institutes of Health (CA087660, CA132630, DA033760, DA032541) and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

References

- 1.Weiss WA, Taylor SS, Shokat KM. Recognizing and exploiting differences between RNAi and small-molecule inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:739–44. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1207-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimwood S, Hartig PR. Target site occupancy: emerging generalizations from clinical and preclinical studies. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:281–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishna R, Herman G, Wagner JA. Accelerating drug development using biomarkers: a case study with sitagliptin, a novel DPP4 inhibitor for type 2 diabetes. AAPS J. 2008;10:401–9. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong DF, Tauscher J, Grunder G. The role of imaging in proof of concept for CNS drug discovery and development. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:187–203. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews PM, Rabiner EA, Passchier J, Gunn RN. Positron emission tomography molecular imaging for drug development. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:175–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner JA. Strategic approach to fit-for-purpose biomarkers in drug development. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:631–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelat AA, Guy RK. Scaffold composition and biological relevance of screening libraries. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:442–6. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0807-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inglese J, et al. High-throughput screening assays for the identification of chemical probes. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:466–479. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigott-Hennkens HM, Dannoon S, Lewis MR, Jurisson SS. In vitro receptor binding assays: general methods and considerations. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:245–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Using photolabile ligands in drug discovery and development. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:64–77. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halvorsen SW, Berg DK. Affinity labeling of neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunits with an alpha-neurotoxin that blocks receptor function. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2547–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paweletz CP, et al. Identification of direct target engagement biomarkers for kinase-targeted therapeutics. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bantscheff M, et al. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals mechanisms of action of clinical ABL kinase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nbt1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cravatt BF, Wright AT, Kozarich JW. Activity-Based Protein Profiling: From Enzyme Chemistry to Proteomic Chemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nodwell MB, Sieber SA. ABPP methodology: introduction and overview. Top Curr Chem. 2012;324:1–41. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patricelli MP, et al. In situ kinase profiling reveals functionally relevant properties of native kinases. Chem Biol. 2011;18:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubota K, et al. Sensitive multiplexed analysis of kinase activities and activity-based kinase identification. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:933–40. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stains CI, et al. Interrogating signaling nodes involved in cellular transformations using kinase activity probes. Chem Biol. 2012;19:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bantscheff M, et al. Chemoproteomics profiling of HDAC inhibitors reveals selective targeting of HDAC complexes. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:255–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Activity-based protein profiling: the serine hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14694–14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato D, et al. Activity-based probes that target diverse cysteine protease families. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nchembio707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu KL, et al. DAGLbeta inhibition perturbs a lipid network involved in macrophage inflammatory responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:999–1007. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen MS, Hadjivassiliou H, Taunton J. A clickable inhibitor reveals context-dependent autoactivation of p90 RSK. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:156–160. doi: 10.1038/nchembio859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgington LE, et al. Functional imaging of legumain in cancer using a new quenched activity-based probe. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;135:174–82. doi: 10.1021/ja307083b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krysiak JM, et al. Activity-based probes for studying the activity of flavin-dependent oxidases and for the protein target profiling of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:7035–40. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verdoes M, et al. A nonpeptidic cathepsin S activity-based probe for noninvasive optical imaging of tumor-associated macrophages. Chem Biol. 2012;19:619–28. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rostovtsev VV, Green JG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. A stepwise Huisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective “ligation” of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Cell surface engineering by a modified Staudinger reaction. Science. 2000;287:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachovchin DA, et al. Academic cross-fertilization by public screening yields a remarkable class of protein phosphatase methylesterase-1 inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015248108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geurink PP, Prely LM, van der Marel GA, Bischoff R, Overkleeft HS. Photoaffinity labeling in activity-based protein profiling. Top Curr Chem. 2012;324:85–113. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salisbury CM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based probes for proteomic profiling of histone deacetylase complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1171–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradner JE, et al. Chemical phylogenetics of histone deacetylases. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tagore DM, et al. Peptidase substrates via global peptide profiling. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:23–5. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross RW, Han X. Lipidomics at the interface of structure and function in systems biology. Chem Biol. 2011;18:284–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Need AB, McKinzie JH, Mitch CH, Statnick MA, Phebus LA. In vivo rat brain opioid receptor binding of LY255582 assessed with a novel method using LC/MS/MS and the administration of three tracers simultaneously. Life Sci. 2007;81:1389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lancelot S, Zimmer L. Small-animal positron emission tomography as a tool for neuropharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long JZ, et al. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn K, et al. Discovery and characterization of a highly selective FAAH inhibitor that reduces inflammatory pain. Chem Biol. 2009;16:411–20. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edgington LE, et al. Noninvasive optical imaging of apoptosis by caspase-targeted activity-based probes. Nat Med. 2009;15:967–73. doi: 10.1038/nm.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edgington LE, Verdoes M, Bogyo M. Functional imaging of proteases: recent advances in the design and application of substrate-based and activity-based probes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi HG, et al. Brain Penetrant LRRK2 Inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:658–662. doi: 10.1021/ml300123a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adibekian A, et al. Confirming target engagement for reversible inhibitors in vivo by kinetically tuned activity-based probes. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10345–8. doi: 10.1021/ja303400u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashworth S, et al. Evaluation of 11C-GSK189254 as a novel radioligand for the H3 receptor in humans using PET. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1021–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.071753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoi F, et al. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:248–59. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erondu N, et al. Neuropeptide Y5 receptor antagonism does not induce clinically meaningful weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Cell Metab. 2006;4:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams J. The development of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:417–21. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arastu-Kapur S, et al. Nonproteasomal targets of the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and carfilzomib: a link to clinical adverse events. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2734–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carmi C, Mor M, Petronini PG, Alfieri RR. Clinical perspectives for irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:1388–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Advani RH, et al. Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Ibrutinib (PCI-32765) Has Significant Activity in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory B-Cell Malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:88–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Honigberg LA, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ledford H. Drug candidates derailed in case of mistaken identity. Nature. 2012;483:519. doi: 10.1038/483519a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Apsel B, et al. Targeted polypharmacology: discovery of dual inhibitors of tyrosine and phosphoinositide kinases. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:691–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skaddan MB, et al. The synthesis and in vivo evaluation of [18F]PF-9811: a novel PET ligand for imaging brain fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:1058–67. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Das Thakur M, et al. Modelling vemurafenib resistance in melanoma reveals a strategy to forestall drug resistance. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wacker SA, Houghtaling BR, Elemento O, Kapoor TM. Using transcriptome sequencing to identify mechanisms of drug action and resistance. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:235–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suwaki N, et al. A HIF-regulated VHL-PTP1B-Src signaling axis identifies a therapeutic target in renal cell carcinoma. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:85ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]