Abstract

Ischemic heart disease evokes a complex immune response. However, tools to noninvasively track leukocytes’ systemic behaviour and dynamics in vivo are lacking. Here, we present a multimodal hot spot imaging approach using an innovative high-density lipoprotein-derived nanotracer with a perfluoro-crown ether payload (19F-HDL) to allow myeloid cell tracking by 19F magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The 19F-HDL nanotracer is additionally labelable with 89Zr and fluorophores to respectively detect myeloid cells by in vivo positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and optical modalities. Using our nanotracer in atherosclerotic mice with myocardial infarction, we observed rapid myeloid cell egress from the spleen and bone marrow by in vivo 19F-HDL-MRI. Concurrently, using ex vivo autoradiographic techniques, we were able to show that circulating pro-inflammatory myeloid cells accumulated in atherosclerotic plaques and the myocardial infarct site. Therefore, this multimodality hotspot imaging approach can be applied to study the complex myeloid cell dynamics in vivo.

Unravelling the immune system’s role in pathophysiological processes has not only deepened and broadened our understanding of disease but has also yielded new therapeutic avenues1. In that context, research focusing on immune cell dynamics is becoming increasingly relevant2,3. A vast body of recent research has shown that atherosclerosis, the underlying cause of ischemic heart disease, is a lipid-driven disease that is also largely dependent on immune cell influx4. Moreover, cardiovascular events themselves mobilize immune cells and accelerate ongoing atherosclerosis5. This contemporary, more complex view of ischemic heart disease has resulted in the first clinical trial targeting inflammation with the goal of reducing the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events6.

Although many different aspects of myeloid cell dynamics in ischemic heart disease have been deciphered7, including their deployment from the bone marrow8 and spleen9, our current knowledge is exclusively based on snapshot immunological assays. Further, it is becoming more evident that these processes interact systemically10–13. Without suitable in vivo readouts, an all-encompassing view of these different processes is difficult to acquire. Therefore, this study’s goal was to develop nanotechnology that can probe different aspects of myeloid cell dynamics in ischemic heart disease by multimodal imaging. We developed and applied so-called high-density lipoprotein (HDL) nanotracers with a lipophilic perfluoro-crown ether (19F-HDL) payload to enable hot spot 19F magnetic resonance imaging (19F MRI) (Fig. 1a). These 19F-HDL nanotracers can be additionally labelled with Zirconium-89 (89Zr) and/or fluorophores for detection by in vivo positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, a variety of ex vivo nuclear methods and optical techniques, such as flow cytometry (Fig. 1a). Here, using this 19F-HDL-facilitated multimodal in vivo imaging approach, we study myeloid cells in the bone marrow and spleen and monitor these cells’ migration and accumulation in inflammatory tissues in mouse models of atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Nanotracer platform with multimodal evaluation in ischemic heart disease.

a. The nanotracer platform consists of a perfluoro-crown ether (PFCE) core surrounded by a phospholipid layer stabilized by apoAI. Additional labeling with Zirconium-89 and BODIPY allows positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and optical assays, respectively. We developed three 19F-HDL nanotracer formulations of varying size: “small (~40 nm)”, “intermediate (~105 nm)” and “large (~180 nm)”; the lines represent their respective dynamic light scattering (DLS)-determined size distribution. b. Myeloid cell dynamics in the context of ischemic heart disease. A mouse is injected with the nanotracer, which accumulates in the spleen and bone marrow as it is taken up by neutrophils (neu), monocytes (mono) and macrophages (mac). Egress from the spleen and bone marrow leads to subsequent nanotracer accumulation at the infarcted myocardium and atherosclerotic plaque.

Developing and characterizing multimodal nanotracers

We present a strategy to incorporate perfluorocarbons into high-density lipoprotein-like nanocarriers. Using this approach, we developed three formulations with varying 19F payloads and sizes. These three differently sized 19F-HDL nanotracers were composed of a perfluoro-crown ether core covered by a corona of phospholipids and apolipoprotein A1 (apoAI). Their hydrodynamic diameters were respectively 40 nm (‘small’), 105 nm (‘intermediate’) and 180 nm (‘large)’, as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS), and all remained stable at 37 °C in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 days (Fig. 1a, Fig. 2ai, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Transmission electron microscopy corroborated these DLS findings and showed a narrow size distribution of mostly spherical structures (Fig. 2aii). In an ensuing in vivo 19F MR imaging study, the differently sized nanotracers were screened for their ability to accumulate in the spleen and bone marrow. Two days post injection, mice were anesthetized and subjected to preclinical MRI using a dedicated 19F/1H combination coil. Anatomical information was acquired using a standard 1H MRI protocol, while hot spot 19F MRI was facilitated by a 19F 3D-FLASH sequence to quantitatively visualize 19F-HDL nanotracers. 19F MRI revealed that the largest nanotracer displayed the most pronounced splenic uptake, while mice injected with the intermediate and small formulations showed splenic uptake levels comparable to those of the liver (Fig. 2aiii). Quantitative analyses of the spleen indicated a significantly higher target-to-background ratio (TBR) for the large nanotracer (24.4 ± 7.3) compared to the small and intermediate formulations (10.4 ± 5.1 and 8.8 ± 2.1, respectively) P < 0.01 (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the largest formulation also displayed the strongest bone marrow uptake in the spine, while liver and kidney uptake did not differ among the three formulations (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Lastly, absolute muscle uptake for all 19F-HDL formulations was similar, thereby justifying its use as ‘background’ signal for TBR calculations (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Fig. 2. Developing and characterizing multimodal nanotracers.

a. i) Schematic overview of 19F-HDL’s different sizes: small (~40 nm, left), intermediate (~105 nm, middle) and large (~180 nm, right) particles. ii) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing different nanotracers’ sizes and shapes (bar represents 200 nm). iii) representative fused 1H and 19F-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images 48 hours post injection (p.i.) of the nanotracers. MRI was repeated for n = 4 (small, intermediate) and n = 6 (large) biologically independent samples. b. Quantification of all three formulations in spleen (left), bone marrow (middle) and liver (right) expressed as target-to-background (TBR) in which muscle serves as “background” signal. n = 4 mice (small, intermediate); n = 6 mice (large). *P=0.001 in spleen, **P=0.0023 for bone marrow. c. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for different cells in spleen (left) and bone marrow (right). n = 8 mice (spleen); n = 6 mice (bone marrow). *P < 0.0001. d. Biodistribution 48 hours after 89Zr-19F-HDL injection in healthy mice with three different labeling strategies, DFO conjugated with apoAI (top), DFO conjugated with liposomes (middle) or C34-DFO incorporated in the liposome layer (bottom). (n = 5 mice per labelling strategy). *P=0.0042 for DFO conjugated with apoAI, *P=0.0005 for DFO conjugated with liposomes, *P=0.0018 for C34-DFO e. Representative fused positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) images at 5 minutes, 1 hour and 48 hours after 89Zr-19F-HDL injection (DFO conjugated with apoAI), including a magnified femur showing bone marrow (bm). Dynamic PET/CT was repeated for n = 4 biologically independent samples. f. Pharmacokinetic curve of 89Zr-19F-HDL in healthy mice. Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n = 3 independent samples for three first time points, n = 5 independent samples for the latter time points). g. Representative fused 1H/19F MRI images longitudinally evaluate 19F-HDL 3, 7 and 14 days p.i. with magnified parts of the spine. The experiments were repeated twice independently with similar results; n = 6 biologically independent samples for each repetition. h. Quantified 19F-HDL signal on different days after injection using longitudinal 19F MRI in the bone marrow (left) and spleen (right) respectively. n = 5 mice, one mouse excluded based on Grubb’s test for outliers. A one-way Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons was used unless otherwise stated. Data are shown as mean±sd in b, c, d, h. Abbreviations: neu=neutrophils, Ly6Chi=Ly6Chigh monocytes, Ly6Clo=Ly6Clow monocytes, mac=macrophages, DC=dendritic cells, lym=lymphocytes, liver (li), spleen (sp), kidneys (ki), bone marrow (spine or bm), percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

Encouraged by the pronounced spleen uptake, we selected the large nanotracer for the ensuing extensive in vivo characterization. In a separate group of mice, fluorescently labelled 19F-HDL was intravenously injected and allowed to distribute for 48 hours, after which the animals were sacrificed for flow cytometry experiments to study the largest nanotracer’s cellular affinity in the spleen and bone marrow. In the spleen, we observed significantly stronger uptake by myeloid cells – macrophages, neutrophils and monocytes – as compared to lymphocytes, while in bone marrow, pro-inflammatory Ly6Chigh monocytes were found to take up most of 19F-HDL, P < 0.01 and P = 0.005 respectively (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). To study its in vivo behaviour quantitatively, we radiolabelled the 19F-HDL nanotracer with the long-lived (78.4 hours) radioisotope Zirconium-89 (89Zr) to enable PET imaging. In contrast to 19F MRI, this imaging method is highly sensitive, but we limited its use to 3 days due to 89Zr’s physical decay half-life. The nanotracer’s core cannot be radiolabeled because of the perfluoro-crown ether’s physicochemical properties and the 19F-HDL formulation procedure. Therefore, we performed three alternative 89Zr-labeling strategies involving conjugating the chelator desferrioxamine B (DFO) with the nanotracer to allow complexation of 89Zr, generating 89Zr-19F-HDL. Free 89Zr was removed by size exclusion chromatography (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The three radiolabeling strategies, involving (i) DFO-functionalized apoAI, (ii) DFO-functionalized phospholipid and (iii) using a lipophilic version of DFO called DFO-C34 showed similar PET imaging patterns, albeit the clearance dynamics (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 1e, 1f) and reproducibility varied. These differences likely result from differences in in vivo remodelling kinetics. For example, phospholipids are known to exchange between lipoproteins avidly, while apoAI is more tightly bound and accumulates in the kidneys, hence the differences in blood half-life and kidney uptake14–16. These data underscore that the apoAI labelling did not impact this protein’s natural function. 89Zr labelling through C34-DFO resulted in an imaging signature most similar to the 19F MRI results. Ex vivo gamma counting two days after 89Zr-19F-HDL injection validated the in vivo findings. For the 180 nm 89Zr-19F-HDL, the spleen showed higher or similar uptake compared to the liver, irrespective of the 89Zr labelling strategy, P < 0.005 (Fig. 2d). PET imaging showed 89Zr-19F-HDL in the circulation 5 minutes post injection (Fig. 2e, arrows) and mostly accumulated in the spleen, liver and kidneys one hour post injection (Fig. 2e). A PET scan 48 hours post injection corroborated Figure 2a’s 19F MRI findings, displaying high uptake in the spleen with substantial uptake in the liver and accumulation in the marrow-rich bone (Fig. 2e). We drew blood at multiple time points and calculated a circulation half-life of 6.2 hours (Fig. 2f, with DFO functionalized apoAI). It must be stressed that owing to the nanotracer’s relative rapid accumulation in the spleen and bone marrow, the differences in remodelling kinetics had little impact on overall biodistribution. Subsequent experiments in Apoe−/− mice were performed with 89Zr-19F-HDL using labelling strategies (ii) and (iii).

The 19F-HDL nanotracer’s in vivo resilience was studied longitudinally in wild type mice (Fig. 2g). The 19F MRI signal remained stable over time in the bone marrow and spleen (Fig. 2h), and flow cytometry quantification of fluorescently labelled nanotracers showed uptake by myeloid cells (CD11b+) (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Importantly, noise and muscle quantified by 19F MRI did not differ over time (Supplementary Fig. 1g).

Based on its ability to track myeloid cells over prolonged periods of time in vivo, we next set out to employ the 19F-HDL nanotracer to study myeloid cell dynamics in ischemic heart disease mouse models by multimodal imaging.

Evaluation of myeloid cell dynamics in atherosclerosis development

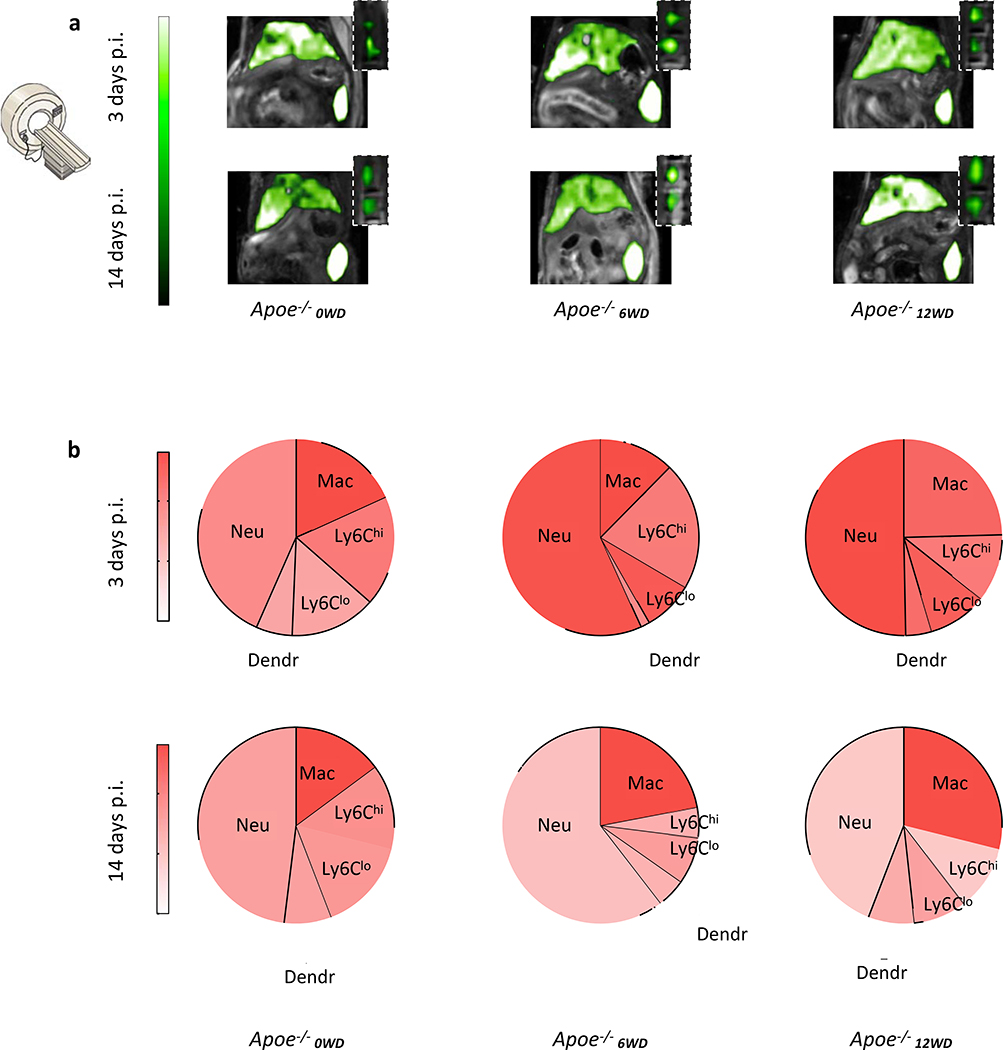

To study myeloid cell dynamics in the context of chronic inflammation, we used the well-established apolipoprotein E knock-out (Apoe−/−) mouse model of atherosclerosis. In these animals, the apoE ligand’s absence in combination with a Western Diet (WD) results in atherosclerotic lesions that progress over time17. We investigated myeloid cell dynamics in different atherosclerosis disease stages in Apoe−/− mice fed a WD for 0, 6 or 12 weeks, referred to as Apoe−/−0WD, Apoe−/−6WD, Apoe−/−12WD. Upon 19F-HDL administration and in line with our findings in wild type mice, we observed high accumulations in spleen and liver at three and fourteen days post injection for all atherosclerotic mice by in vivo 19F MRI (Fig. 3a). In addition, the bone marrow signal in the spine was similar for all groups (Fig. 3a). To study the subsets of myeloid cells associated with our nanotracer at different stages of atherosclerosis development, cells were extracted from spleens that were harvested after sacrificing age and diet matched Apoe−/− mice (Fig. 3b). The nanotracer primarily labelled neutrophils, macrophages and Ly6Chigh monocytes (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Characterization in atherosclerosis.

a. Representative images of 1H/19F magnetic resonance imaging of upper abdominal area at 3 and 14 days post 19F-HDL injection with magnifications of the spine containing bone marrow. Similar results were obtained in six (Apoe−/−0WD, Apoe−/−6WD) and five (Apoe−/−12WD) independent experiments. b. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for different myeloid cell subsets in spleen at 3, and 14 days post BODIPY-19F-HDL injection. The size of each wedge represents the relative contribution of each cell type to the total number of myeloid cells in the spleen. n = 5 for all groups Apoe−/−0WD and for Apoe−/−12WD 3 days; n = 6 for all groups Apoe−/−6WD and for Apoe−/−12WD 14 days. Atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice had been fed Western diet for 0 (Apoe−/−0WD), 6 (Apoe−/−6WD) or 12 (Apoe−/−12WD) weeks at the time of injection.

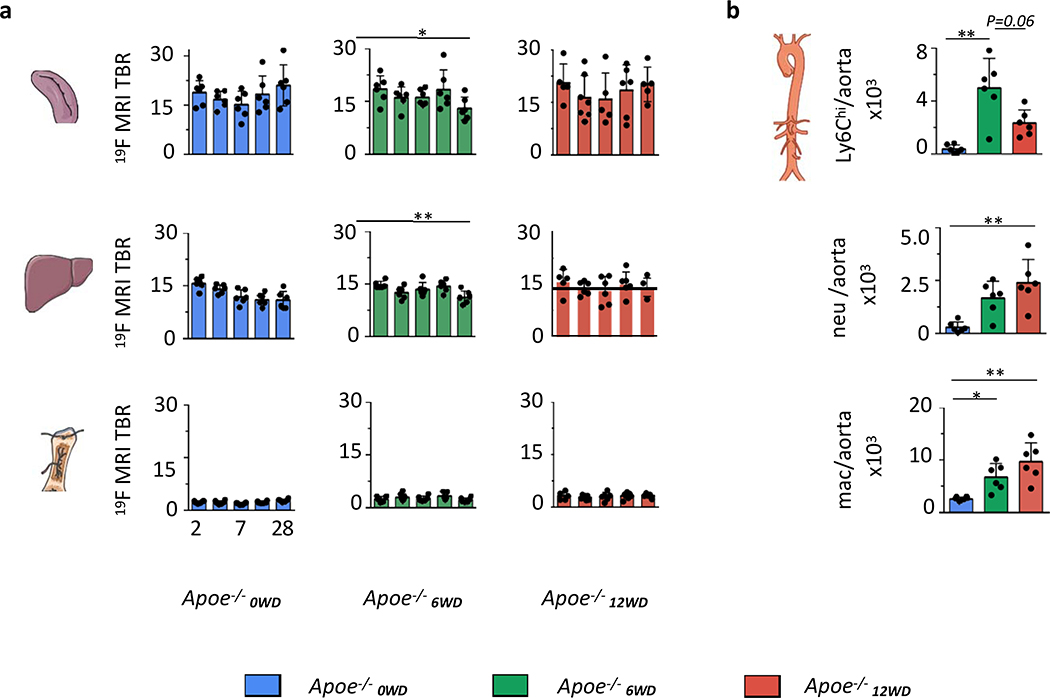

Subsequently, we performed quantification of the 19F MRI signal in the spleen, liver and bone marrow at different stages during atherosclerosis development (Fig. 4a). Over a time course of 28 days, 19F MRI signal in spleen, liver, bone marrow and kidney (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) remained stable for all groups, with one exception. The spleen and liver 19F MRI signal in Apoe−/−6WD dropped significantly at 28 days post injection, P = 0.03 (Fig. 4a). This decrease in signal was accompanied by increased Ly6Chigh monocytes in aortas of Apoe−/−6WD as compared to Apoe−/−0WD, P = 0.002, while no difference was found with Apoe−/−12WD, P = 0.06 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 3c). The 19F MRI-visualized decrease in 19F MRI signal in Apoe−/−6WD can be the result of increased Ly6Chigh monocyte recruitment from bone marrow and spleen to the plaque (Fig. 4b) that occurs in the intermediate stages of atherosclerosis development18. In the advanced plaques of Apoe−/−12WD, local proliferation dominates macrophage accumulation in the vessel wall19, which explains the increased myeloid cell numbers in the vessel wall in the absence of myeloid cell egress from the spleen.

Fig 4. Longitudinal evaluation of myeloid cell dynamics during atherosclerosis development.

a. Quantification of 19F MRI signal expressed as target-to-background ratio (TBR) at 2, 3, 7, 14 and 28 days for spleen, liver and bone marrow. n = 6 mice for Apoe−/−0WD; n = 6 mice for Apoe−/−6WD; for Apoe−/−12WD n = 5 mice at 2 d, 28 d, n = 7 at 3d, n = 6 at 14 d and n = 5 for spleen (one sample is excluded based on Grubb’s test for outlier) and n = 6 for bone marrow and liver at 7 d. One sample is excluded completely in Apoe−/−12WD at 7 days due to non-usable MRI data. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used for spleen and liver in Apoe−/−6WD between 2 and 28 days, *P=0.0152 and *P=0.0022, respectively. b. Flow cytometry quantification of cells in the aorta. n = 6. All data are shown as mean±sd. A one-tailed Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons was used unless otherwise stated. *P=0.0015 for Ly6Chi, *P=0.0039 for neutrophils and *P=0.0023 for macrophages in the aorta. Abbreviations: Ly6Chi=Ly6Chigh monocytes, neu=neutrophils, mac=macrophages. Atherosclerotic mice had been fed Western diet for 0 (blue), 6 (green) or 12 (red) weeks at the time of injection.

In addition to identifying increased myeloid cell departure from the spleen in Apoe−/−6WD, this extensive longitudinal evaluation in atherosclerotic mice also showed the 19F-HDL nanotracer to be stable over time.

Imaging of myeloid cell dynamics in myocardial infarction

To study the effects of myocardial infarction (MI) on myeloid cell dynamics in atherosclerosis, we fed Apoe−/− a WD for 6 weeks and then subjected them to either permanent (MI+) or transient ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, causing ischemia reperfusion injury (I/R)20,21. The latter is a relevant model of MI patients in whom the blockage of the coronary artery is treated, e.g., by stenting22. Two days prior to inducing ischemia, 19F-HDL was injected and allowed to accumulate in the spleen and bone marrow (see outline Fig. 5a). We observed a rapid decline in 19F MRI TBR in bone marrow and spleen one day after MI, for both permanent ligation and I/R, compared to non-MI controls, all P < 0.005 except for bone marrow in I/R P < 0.02 (Fig. 5b, c). A similar decrease was observed for the liver but not the kidneys at 3 days, P < 0.005 (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Mice injected with 89Zr-19F-HDL and subjected to PET imaging one day after MI had less pronounced hematopoietic organ signal decrease, while liver signal did not differ among the groups, all based on gamma counting (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). When 19F MR imaging was repeated 14 days post injection, the differences between mice with MI (permanent ligation or I/R) and without MI persisted, P < 0.005 (Fig. 5d, e, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Other than tissues and organs directly involved in myeloid cell dynamics, the 89Zr-19F-HDL distribution did not significantly differ between MI and non-MI Apoe−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 4d). The spleen acts as a reservoir that, in the event of MI or stroke, rapidly deploys large amounts of immune cells9. In addition, the liver and bone marrow serve as harbours for neutrophils that are released during acute injury23,24, phenomena that have thus far only been studied using ex vivo readouts.

Fig. 5. Multimodal imaging myeloid cell egress from hematopoietic organs and recruitment to inflammatory sites in myocardial infarction.

a. Schematic overview of performed experiments. b. Representative 1H/19F magnetic resonance images of Apoe−/− mice without (left) and with permanent (MI+, center) or transient (I/R, right) myocardial infarction and c. quantification of 19F-HDL in bone marrow, spleen and liver 3 days post 19F-HDL injection (p.i.). expressed as target-to-background (TBR) in which muscle serves as “background” signal. n = 6 for MI, I/R and control groups except for MI+ spleen where n = 5, one sample is excluded based on Grubb’s test for outliers. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U- test was used for bone marrow (*P=0.0022), spleen (*P=0.0043) and liver (*P=0.0022) d. Representative 1H/19F MR images of Apoe−/− mice without (left) and with permanent (center) or transient (right) myocardial infarction and e. quantification of 19F -HDL in bone marrow, spleen and liver 14 days p.i. n = 6 for all groups. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U- test was used for bone marrow (*P=0.0043), spleen (*P=0.0022), and liver (*P=0.0022). f. Representative autoradiography of sliced heart sections and whole aortas from Apoe−/− mice without (left) or 1 day after permanent (center) or transient (right) myocardial infarction 3 days after 89Zr-19F-HDL injection. n = 7 (MI-); n = 8 (MI+); n = 4 (I/R). g. Gamma counting quantification of whole hearts and aortas from Apoe−/− mice without (green) or 1 day after permanent (red) or transient (yellow) myocardial infarction and 3 days p.i. 89Zr-19F-HDL. n = 9 for MI-, n = 11 for MI+ and n = 4 for I/R groups. Two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test was used. *P=0.0276 MI+ heart %ID/g compared to MI-, P=0.3418 for MI+ aorta %ID/g compared to MI-. In b,d experiments were repeated in n = 6 mice per group with similar results. All data are shown as mean±sd.

Abbreviations: I/R = ischemia/reperfusion, bm or spine indicates bone marrow, percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). Apoe−/− without MI are indicated in green, with MI are indicated in red (permanent ligation) and yellow (transient ligation).

Pro-inflammatory cells deploying from the hematopoietic organs into the circulation can aggravate peripheral inflammation, for example in atherosclerotic plaques5. In the current study, we observed decreased neutrophil levels in the bone marrow one day after permanent ligation, while in the circulation elevated levels of pro-inflammatory myeloid cells – neutrophils and Ly6Chigh monocytes – made up more than 50% of all circulating leukocytes (neutrophils: 49.6% ± 12.9%; Ly6Chigh monocytes: 8.5% ± 2.0%, P = 0.008 and P = 0.03, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Upon 89Zr-19F-HDL administration, increased myeloid cell uptake in the infarct and remote myocardium was observed in mice after permanent ligation (MI+) by autoradiography and confirmed by gamma counting of the whole heart, as compared to non-infarcted hearts, P = 0.02 (Fig. 5f, g). In I/R mice, myeloid cell recruitment to the infarct area was not significantly elevated, P = 0.15 (Fig. 5f, g). Additionally, the atherosclerotic aortic roots of Apoe−/− mice subjected to permanent MI showed an increased trend compared to non-MI mice, although no significant differences were found by gamma counting (Fig. 5g). In age-matched mice, flow cytometry identified an upsurge of neutrophils and Ly6Chigh monocytes in the ischemic myocardium one day after permanent ligation, accompanied by death of resident macrophages, P < 0.005 for neutrophils and monocytes, P < 0.01 for macrophages, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). Similarly, we observed massive neutrophil and Ly6Chigh monocyte influx in whole aortas (P = 0.008 and P < 0.02 respectively), while macrophage numbers were unaffected (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d).

In summary, our nanotracer multimodal imaging approach revealed pro-inflammatory cell egress from hematopoietic organs in two different models of MI, in vivo and noninvasively. This process could be monitored for up to at least 12 days after MI using 19F MR imaging. As a consequence of myeloid cell deployment, we concurrently observed enhanced accumulation of these pro-inflammatory cells at peripheral inflammation sites by autoradiography and gamma counting.

Conclusions

Here we describe a systems imaging approach based on myeloid cell-specific and multimodal nanotracers. The nanotracer can label myeloid cells in vivo to map their dynamics in ischemic heart disease using a combination of in vivo hot spot 19F MRI and PET imaging, ex vivo autoradiography and gamma counting, as well as optical techniques, including flow cytometry. Using this approach, we exploit the integrative strengths of PET/CT, optical and MR imaging. Labelling of the nanotracer with 89Zr allows short-term studying of dynamics and biodistribution at high levels of sensitivity, while at a cellular level optical imaging can be used to study the associated cell subsets. Due to the physical decay, PET imaging is not appropriate to study systemic inflammatory changes over prolonged periods of time, and therefore we limited it to three days. By incorporating a fluorine core, our nanotracer allows quantification of immune cell dynamics up to 28 days after injection, however at less sensitivity compared to PET imaging

First, we screened different sized nanotracers for favourable uptake in the spleen and bone marrow, hematopoietic organs that produce and deploy myeloid cells upon specific inflammatory triggers. The largest nanotracer displayed unusually high spleen uptake, as deduced from a TBR of ~24 as compared to ~10 for the smaller nanotracer. In the context of atherosclerosis progression, we identified egress from the spleen by 19F MRI, while flow cytometry showed accumulated pro-inflammatory monocytes in the aortas. When atherosclerotic mice were subjected to permanent or transient myocardial infarction, we observed significantly decreased fluorine signal in the spleen, bone marrow and liver by 19F MRI, which was corroborated by PET imaging. At the same time, flow cytometry identified larger myeloid cell populations in the blood, the infarcted myocardium and the aorta, increases that coincided with enhanced myeloid cell accumulation as observed by ex vivo nuclear techniques. The apparent signal decline by 19F MRI from the liver as a consequence of myocardial infarction was an unexpected finding and warrants further research.

We developed a nanotracer-based multimodal imaging approach to study immune cell dynamics longitudinally on a systemic level. In the current study, we used this imaging approach alongside cell sorting techniques to unravel regulatory pathways and pathophysiological processes in cardiovascular disease. Future research should include scaling up the nanotracer production and amending of imaging protocols to clinical systems to confirm our findings in translational studies. Ultimately, we anticipate its use in other inflammatory diseases and to aid in the development and evaluation of immunotherapies.

Methods

Formulating perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether (PFCE) loaded 19F-HDL nanotracers

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC, 59 mg) and 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (MHPC, 41 mg) (both Avanti Lipids) were dissolved in 2 mL of chloroform. The chloroform solution was slowly dripped in hot PBS (10 mL, 80 °C). The obtained solution was stirred for another 5 minutes at this temperature and then allowed to cool to room temperature. If necessary, additional PBS was added to obtain a total volume of 10 mL. The lipid solution (0.5 mL), PBS (4.5 mL) and perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether (PFCE, Oakwood Chemicals), 20 μL for ~36 nm particles, 80 μL for 105 nm particles, 160 μL for 180 nm particles were sonicated for 30 minutes at 0 °C using a 150 V/T ultrasonic homogenizer working at 30% power output for tip sonication. Apolipoprotein A1 (apoAI, purified in house from human HDL) (0.5 mg) was added and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for at least 12 hours after which the mixture was shaken and left to stand for 30 seconds. Any precipitate formed was discarded and the remaining solution was transferred to a Vivaspin tube (Sartorius Biotech) (100 kDa MWCO for ~36 and ~105 nm sized particles, 1 MDa MWCO for ~180 nm particles). The tube was spun at 4000 g at 4°C until the solution was concentrated to ~0.5 mL, and then the particles were resuspended by repeatedly moving them up and down a pipette. To determine particle size, an aliquot (10 mL) of the final particle solution was diluted in PBS (1 mL) and analysed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine the mean of the number average size distribution. DLS measurements were performed on a Brookhaven Instrument Corporation ZetaPals analyser. The mean of the number distribution was taken as the particles size. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma Aldrich unless stated otherwise.

Determining PFCE concentration by 19F NMR

To determine the PFCE concentration in the prepared nanotracers, a solution containing nanotracers (90 vol %), D2O (10 vol %) and a known amount of sodium trifluoroacetate (NaTFA) was prepared. The solution was analysed by 19F NMR and the PFCE concentration determined using NaTFA as an internal standard. 19F NMR samples were analysed using a Bruker 600 ultrashield magnet connected to a Bruker advance 600 console. Data were processed using Topspin version 3.5 pl 7.

Modifying 19F-HDL nanotracers with BODIPY-cholesteryl

Cholesteryl 4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-dodecanoate (BODIPY-cholesteryl) was obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (catalog #C3927MP). To prepare nanotracers containing the BODIPY-cholesteryl dye the exact same protocol as for the unlabelled particles was used, except that BODIPY-cholesteryl was added to the lipid mixture at 1.0 wt % of the lipid amount used.

Functionalizing nanotracers with desferrioxamine B (DFO) for radiolabeling

Three strategies were pursued, either involved the DFO labelling of apoAI (strategy 1) or incorporation of a DSPE-DFO or aliphatic C34-DFO conjugate (strategies 2 and 3, respectively). While all labelling strategies resulted in stable 89Zr-labeled nanotracers, it was found that C34-DFO-based labelling strategy 3 is most reproducible.

Strategy 1: DFO labelling apoA1 in preformulated nanotracers. DFO was conjugated to apoAI by basifying premade nanotracers in approximately 1–3 mL of PBS using a carbonate buffer (1 M, pH 9) until a pH of ~8.5 was reached. The apoAI concentration was kept between 1–10 mg/mL (assuming all apoAI used in formulating the nanotracers was recovered). p-NCS-Bz-DFO (Macrocyclics) was dissolved in DMSO to obtain 5 mg/mL solution and added to the nanotracers until a 2-fold molar excess of p-NCS-Bz-DFO (753 g/mol) over apoAI (28,000 g/mol) was achieved. To minimize the influence of DMSO on the nanotracers, the p-NCS-Bz-DFO solution was added in aliquots of 5 μL and the total DMSO concentration kept below 5 vol. %. The solution containing nanotracers and p-NCS-Bz-DFO was incubated at 37 °C in a water bath for 2 hours and subsequently transferred to a Vivaspin centrifugal filtration tube (100 kDa MWCO). The Vivaspin tube was spun at 4000 g and 4°C until a volume of 1–2 mL was obtained, PBS (2 mL) was added and the solution was again concentrated to a volume of 1–2 mL. This washing step was repeated twice, after which the particles were resuspended by repeatedly moving them up and down a pipette.

Strategies 2 and 3: Incorporating DSPE-DFO or C34-DFO in the nanotracers. To prepare nanotracers containing DSPE-DFO or C34-DFO, the exact same protocol as for formulating the unlabelled nanotracers was used, except that either DSPE-DFO or C34-DFO (synthesized using procedures previously reported by us)14,15 was added to the lipid mixture at 0.5 wt. % of the amount of lipids used.

Radiolabelling DFO-bearing nanotracers with 89Zr

Zirconium-89 (89Zr) oxalate was made at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center using an EBCO TR19/9 variable beam energy cyclotron via the 89Y(p,n)89Zr reaction and purified using a previously published method25, resulting in a 89Zr solution in 1M aqueous oxalic acid. The 89Zr solution was diluted with PBS and aqueous sodium sulphate solution (1 M) added until a pH of 6.8–7.4 was reached. This solution was added to a solution of DFO-functionalized nanotracers (either containing DSPE-DFO, C34-DFO or apoAI-DFO) and the obtained solution (1–2 mL total) incubated for 1 hour in a thermoshaker at 37 °C. The Zr-labelled nanotracers were purified using a PD-10 column (General Electric, Sephadex G-25 M) using PBS as the eluent. In the case of DSPE-DFO or C34-DFO labelled nanotracers (strategy 2 or 3), the nanoparticles were additionally washed 3 times with PBS by centrifugal filtration using a 10 kDA MWCO Vivaspin tube. Radiochemical purity was assessed using SEC radio-HPLC, typically a purity above 95 % was achieved. Radiochemical yields were typically between 50–90 % for strategy 1, and reproducibly above 80 % for strategies 2 and 3. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) radio-high performance liquid chromatography (radio-HPLC) analyses were performed on a Shimadzu system equipped with a Superdex 10/300 SEC column using a flow rate of 1 ml/min and demi water as the eluent. A Lablogic Scan-RAM radiodetector was used.

Animals

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and followed National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal welfare.

Mouse models

Female Apoe−/− (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J, 8 weeks old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and fed a cholesterol-enriched, Western diet (WD, Harlan Teklad TD.88137, 42 % calories from fat) for either 0, 6 or 12 weeks before injection and remained on this diet for the remainder of the experiment. Due to the elevated circulating LDL concentrations resulting from their lack of apolipoprotein E, these animals develop atherosclerotic plaques, especially at locations with disturbed flow, i.e. the aortic root, and the aortic arch with its branches1,2. Age matched female C57BL/6J received regular chow and served as controls.

Myocardial infarction

Age-matched 8-weeks-old female Apoe−/− mice received a WD for 6 weeks before undergoing permanent or temporary ligation of the left descending artery (LAD) to induce a myocardial infarction, as described in full detail here3. Anaesthesia was induced using Ketamine (100 mg/kg) with Xylazine (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally and maintained using isoflurane. Analgesia was provided using Buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) before and 12 hours after surgery. The left side of thorax was shaved and disinfected, a thoracotomy was performed using the 5th or 4th intercostal space and a retractor was used to keep the surgical field exposed. Attention was paid not to puncture the left lung. Temporary ligation was maintained for 40 minutes by a small tube between the ligation suture and LAD. All infarctions were created 2 days after injection with either 19F-HDL or 89Zr-19F-HDL. For more details, see outline (Fig. 5a).

MR imaging

C57/BL6 or Apoe−/− mice were injected with 1.3 μL of 19F-HDL solution per gram of body weight via the lateral tail vein. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare)/oxygen gas mixture (2% for induction, 1 % for maintenance), and images were acquired on a 7T Bruker BioSpec 70/30 scanner (Bruker) using a 19F/1H birdcage coil for mice (MR Coils B.V.). After acquiring localizer scans, a hydrogen (1H) 3-dimensional (3D) fast low angle shot (FLASH) sequence was performed to identify the liver and spleen (orientation, coronal; repetition time [TR], 20 ms; echo time [TE], 3.7 ms; field-of-view [FOV], 60 × 60 × 30 mm3; matrix, 256 × 128 × 128; reconstructed voxel size, 0.23 × 0.23 × 0.23 mm3; flip angle 20°; signal averages, 2; acquisition time, 6min8s). An additional 1H TURBO rapid imaging with refocused echoes (RARE), T2-weighted sequence, was also acquired for this purpose (orientation, coronal; repetition time [TR], 3000 ms; echo time [TE], 33 ms; number of slices, 27; slice thickness, 1 mm; slice gap, 0.1 mm; field-of-view [FOV], 60 × 30 mm2; matrix size, 256 × 128, RARE factor 8, pixel size 0.23 × 0.23 mm2; signal averages, 12; acquisition time, 9m36s). Next, the coil was switched to 19F mode. After centring the frequency on the perfluoro-crown ether (PFCE) peak, a 3D FLASH sequence was performed to quantify 19F signal in the liver and spleen (orientation, coronal; repetition time [TR], 20 ms; echo time [TE], 2.9 ms; field-of-view [FOV], 60 × 60 × 30 mm3; matrix, 64 × 32 × 32; voxel size, 0.94 × 0.94 × 0.94 mm3; flip angle 25°; signal averages, 200; acquisition time, 1h8min16s).

PET/CT imaging

C57/BL6 or Apoe−/− mice were injected with the 89Zr-19F-HDL (0.07 – 0.30 mCi) in 100 μL PBS solution via the lateral tail vein. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL)/oxygen gas mixture (2% for induction, 1 % for maintenance), and a scan was performed using a Mediso nanoScan PET/CT (Mediso, Budapest, Hungary). Wild type mice were imaged immediately after injection followed by a second imaging 48 hours later. Apoe−/− mice were imaged 72 hours post injection. A whole body CT scan was performed (energy 50 kVp, current 180 μAs, isotropic voxel size at 0.25 × 0.25 mm) followed by a 20 or 60 minutes PET scan. Reconstruction for the PET data utilized the CT acquisition for attenuation correction. Reconstruction was performed using the TeraTomo 3D reconstruction algorithm using the Mediso Nucline software. The coincidences were filtered with an energy window between 400 – 600 keV. The voxel size was isotropic with 0.6 mm width and the reconstruction was applied for two full iterations, 6 subsets per iteration.

Image analysis

All obtained imaging data were analysed using Osirix (5.6) software (OsiriX Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland). Regions of interest (ROI) were measured by manually drawing a contour on different tissues. In the case of 19F MRI, a target-to-background ratio was calculated by dividing the mean of multiple (>10) maximum ROI values (ROImax) from tissue of interest by the mean of multiple ROImax from muscle tissue.

Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution in mice

Blood radioactivity half-life was determined by serial blood draws from the tail vein at 1, 5, 30, 60 and 120 minutes and 6, 24 and 48 hours after 89Zr-19F-HDL injection. Blood was weighed and counted using a Wizard2 2480 automatic gamma counter (Perkin Elmer). After scans were completed, animals were sacrificed and perfused, and tissues (brain, heart, lungs, aorta, spleen, liver, kidneys, skeletal muscle and bone marrow) were collected, blotted and weighed in pre-weighed tubes. Radioactivity content was measured by gamma counting, and tissue radioactivity concentration was calculated and expressed as % injected dose per gram (%ID/g) or normalized by activity found in muscle tissue.

Autoradiography

Digital autoradiography was performed to determine Zirconium-89 distribution within the whole aorta and infarct. Samples were placed in a film cassette against a phosphorimaging plate (BASMS-2325, Fujifilm) for 1.5 h (whole aortas) or, 2h (hearts) and stored at −20 °C. Phosphorimaging plates were read at a pixel resolution of 25 μm with a Typhoon 7000IP plate reader (GE Healthcare). Quantification was carried out using ImageJ software.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry analysis, blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and collected in an EDTA-coated tube. Mice were subsequently perfused through the left ventricle with 10 mL cold PBS. Femur and spleen were harvested. The aorta, from aortic root to the iliac bifurcation, was collected. The infarcted heart tissue was collected and weighed. The aorta was minced and digested using an enzymatic digestion solution containing liberase TH (4 U/mL) (Roche), deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I (40 U/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) and hyaluronidase (60 U/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. Heart tissue was minced and digested using an enzymatic digestion solution containing DNAse (60 U/mL), collagenase I (450 U/mL), collagenase XI (125 U/mL) and hyaluronidase (60 U/mL) (all Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. Aortas and heart tissues were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C under agitation. Cells were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer and washed with FACS buffer (DPBS with 1% FBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.1%NaN3 and 1mM EDTA). Blood was incubated with lysis buffer for 4 minutes and washed with FACS buffer and repeated 2 more times. Spleens were weighed. A piece of 25 mg was mashed, filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer, incubated with lysis buffer for 4 minutes and washed with FACS buffer. Bone marrow was flushed out of the femur with PBS, filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer, incubated with lysis buffer for 30 seconds and washed with FACS buffer. Single cell suspensions were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies: anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), anti-F4/80 (clone BM8), anti-CD11c (clone N418), anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11), anti-Ly6C (clone AL-21) and a lineage cocktail (Lin) containing anti-CD90.2 (clone 53–2.1), anti-Ter119 (clone TER119), anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136), anti-CD49b (clone DX5), anti-CD45R (clone RA3–6B2), anti-CD103 (clone 2E7) and anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8). Antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, Biolegend or BD Biosciences. Macrophages were identified as CD45+, CD11bhigh, Lin−/low, CD11clow and F4/80hi. Monocytes were identified as CD45+, CD11bhigh, Lin−/low, CD11clow and Ly6Chigh/low. Neutrophils were identified as CD45+, CD11bhigh and Lin+. Lymphocytes were identified as CD45+ and Lin+. CD11b+ cells were identified as CD45+ and CD11b+. To measure 19F-HDL’s cellular specificity, BODIPY-19F-HDL was intravenously injected 48 hours before euthanasia. BODIPY uptake was measured in the FITC channel. Mean fluorescence intensity was corrected to fluorescent bead signal (Sphero AccuCount Fluorescent Particles, Spherotech). Data were acquired on a Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analysed using FlowJo v10.4.0 (Tree Star).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences were evaluated using two-sided Mann-Whitney test (between 2 groups) or a student’s t-test for repeated measures (between 2 groups). For differences among more than 2 groups, a Kruskal-Wallis was followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons unless otherwise stated. For all tests, α < 0.05 represents statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism®, Version 6.0c.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the “De Drie Lichten” Foundation in The Netherlands (M.L.S.); American Heart Association 17PRE33660729 (M.L.S.) and 16SDG3139000, (C.P.M.), German Research Foundation grant MA 7059/1 (A.M.), HO 5953/1-1, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants (HL096576, HL117829, HL139598 and HL128264) and the MGH Research Scholar Award (M.N. and F.K.S.); Dutch Applied and Engineering Sciences (TTW) grant #14716 (G.J.S); National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL118440, R01 HL125703, R01 HL144072 and ZonMW Vidi 91713324 and Vici 91818622 (W.J.M.M.) and NIH grants R01EB009638 and P01HL131478 (Z.A.F.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permission information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Moore KJ & Tabas I Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 145, 341–355 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yona S et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity 38, 79–91 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geissmann F et al. Development of Monocytes, Macrophages, and Dendritic Cells. Science (80-. ). 327, 656–661 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swirski FK & Nahrendorf M Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science 339, 161–6 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutta P et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature 487, 325–329 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker PM et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med NEJMoa1707914 (2017). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahrendorf M Myeloid cell contributions to cardiovascular health and disease. Nat. Med 24, 711–720 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herisson F et al. Direct vascular channels connect skull bone marrow and the brain surface enabling myeloid cell migration. Nat. Neurosci (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0213-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swirski FK et al. Identification of Splenic Reservoir Monocytes and Their Deployment to Inflammatory Sites. Science (80-. ). 235, 612–616 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tawakol A et al. Relation between resting amygdalar activity and cardiovascular events: a longitudinal and cohort study. Lancet 6736, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thackeray JT et al. Myocardial Inflammation Predicts Remodeling and Neuroinflammation After Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 71, 263–275 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidt T et al. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med 20, 754–8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth S et al. Brain-released alarmins and stress response synergize in accelerating atherosclerosis progression after stroke. Sci. Transl. Med 10, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pérez-Medina C et al. A Modular Labeling Strategy for In Vivo PET and Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging of Nanoparticle Tumor Targeting. J. Nucl. Med 55, 1706–1712 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang J et al. Immune cell screening of a nanoparticle library improves atherosclerosis therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 201609629 (2016). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609629113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez-Medina C et al. In Vivo PET Imaging of HDL in Multiple Atherosclerosis Models. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima Y, Plump AS, Raines EW, Breslow JL & Ross R ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler. Thromb 14, 133–40 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swirski FK et al. Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. J. Clin. Invest 117, 195–205 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins CS et al. Local proliferation dominates lesional macrophage accumulation in atherosclerosis. Nat Med 19, 1166–1172 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panizzi P et al. Impaired Infarct Healing in Atherosclerotic Mice With Ly-6ChiMonocytosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 55, 1629–1638 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Elverfeldt D et al. Dual-contrast molecular imaging allows noninvasive characterization of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury after coronary vessel occlusion in mice by magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 130, 676–687 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heusch G et al. Cardiovascular remodelling in coronary artery disease and heart failure. Lancet 383, 1933–1943 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolaczkowska E & Kubes P Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 13, 159–175 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soehnlein O Multiple roles for neutrophils in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res 110, 875–888 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland JP, Sheh Y & Lewis JS Standardized methods for the production of high specific-activity zirconium-89. Nucl. Med. Biol 36, 729–739 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for Method section

- 1.Nakashima Y, Plump AS, Raines EW, Breslow JL & Ross R ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler. Thromb 14, 133–40 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plump AS et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 71, 343–53 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarnavski O et al. Mouse Cardiac Surgery: Comprehensive Techniques for the Generation of Mouse Models of Human Diseases and Their Application for Genomic Studies. Physiol. Genomics 349–360 (2003). doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00041.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).