Abstract

A mixed-method approach was used to explore and compare self-forgiveness, guilt, shame, and parental stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and parents of neurotypical (NT) children. The data were obtained by the Heartland Forgiveness Scale (Thompson et al., 2005), Guilt and Shame Experience Scale (Maliňáková et al., 2019), Parental Stress Scale (Berry & Jones, 1995) and by open-ended questions. The research sample consisted of 143 parents of children with ASD and 135 parents of NT children from Slovakia. The regression analysis confirmed that guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness explained 23% of the variance in parental stress, while the only significant negative predictor was self-forgiveness. Furthermore, shame mediated the pathway between self-forgiveness and parental stress in parents of children with ASD. Parents of children with ASD experience more shame than parents of NT children. The qualitative analysis obtained a more comprehensive understanding of both groups. Parents of children with ASD mostly experienced shame in regard to their child’s inappropriate behavior or it being misunderstood by society, while parents of NT children mostly did not feel ashamed of their parenting. Acceptance, social support, religious beliefs, and love from the child were the most often mentioned factors helping self-forgiveness in parents of children with ASD. We highlight the importance of self-forgiveness as a potential coping mechanism for parental stress and suggest focusing on negative aspects of shame in parents of children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism, Guilt, Parental stress, Self-Forgiveness, Shame

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder is classified as a pervasive developmental disorder with an ambiguous etiology and is a lifelong condition (Faras et al., 2010). The disorder is characterized mainly by deficits in social communication and interaction, but also significant behavioral stereotypes (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Deficits in these areas can often result in limited independence and the person requiring continuous lifelong care, usually provided by the parents.

Parenting children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be very demanding and stressful. The research largely suggests that parents of children with ASD have higher levels of parental stress than parents of neurotypical (NT) children (Zablotsky et al., 2013) and even higher levels than parents of children with other disabilities (Hayes & Watson, 2013). Parents of ASD children have to cope with their children’s various behavioral and emotional problems (for example sleep problems, attention problems, self-injuries or aggressiveness). Giovagnoli et al. (2015) found that these behavioral and emotional problems in preschool children with ASD are strong predictors of parental stress.

Children with ASD can also have visibly atypical and different behavior patterns, which may be exhibited in a variety of social contexts (Faras et al., 2010). Parents often have to cope with hostile glances, especially when the child’s behavior is socially inappropriate. Sometimes, parents of children with ASD encounter criticism from other people who make judgements about their child's behavior or their parenting practices (Ludlow et al., 2012). Since society does not always accept “different behavior” this can lead to stigmatization (Zhou et al., 2018) and feelings of guilt and shame (Burrell et al., 2017). These moral emotions are elicited through self-reflection and self-evaluations about one’s behavior and may be associated with various psychopathological symptoms (Tangney et al., 2007).

Negative feelings of guilt and shame along with parental stress can be discouraging and can have a potentially harmful effect on the parents’ mental health (Burrell et al., 2017; Ghoreishi et al., 2018; Kuhn & Carter, 2006). Therefore, it is important to focus on various coping mechanisms. There is evidence that parents of children with ASD may find both social support (Ilias et al., 2018; Weinberg et al., 2021) and self-compassion (Neff & Faso, 2014; Wong et al., 2016) helpful. Furthermore, emerging research indicates that forgiveness may play a positive role (Oti-Boadi et al., 2020; Weinberg, et al., 2021). Forgiveness is understood to be an emotion-focused coping strategy that helps to reduce stress by replacing negative feelings and thoughts with positive ones (Worthington, 2013). However, thus far only one study has examined self-forgiveness in parents of children with ASD, and it showed a negative association with parental stress (Melli et al., 2016) but did not take feelings of guilt and shame into consideration. Therefore, our study expands on previous research and focuses on self-forgiveness and its potential association with feelings of guilt and shame, as well as parental stress in parents with ASD children.

Parental Stress

Providing daily care for children with ASD can be challenging, especially during childhood. In addition to stereotypical behaviors and deficits in communication or social interaction, children with ASD may exhibit a whole spectrum of emotional and behavioral problems, e.g., hyperactivity, self-injury, sensory difficulties, tantrums, and aggression toward others (Giovagnoli et al., 2015). These problems may be associated with impaired family functioning (Walton, 2019), a reduction in the parent’s quality of life (Adams et al., 2020), increased symptoms of depression and anxiety (Al-Farsi et al., 2016), and higher levels of parental stress. A considerable number of studies have confirmed that parents of children with ASD have higher levels of parental stress than parents of NT children (Giovagnoli et al., 2015; Zablotsky et al., 2012) including during the COVID-19 pandemic (Polónyiová et al., 2022), or even parents of children with other disabilities (Hayes & Watson, 2013). There is also fairly extensive research into the factors potentially associated with the heightened parental stress and factors that may protect parents (Drogomyretska et al., 2020; Miranda et al., 2019; Neff & Faso, 2014).

Davis and Carter (2008) suggested that parents of younger children with ASD experience higher stress levels, probably due to recent diagnosis and subsequent adaptation. The severity of the possible symptomatology, e.g., poorer verbal/non-verbal IQ, impaired adaptive skills, or increased repetitive behaviors (Webb et al., 2017), has been associated with higher parental stress (Ilias et al., 2018; Miranda et al., 2019). Other factors, like the child’s lack of schooling (Derguy et al., 2016) as well as behavioral and emotional problems (Giovagnoli et al., 2015), have been shown to predict higher parental stress. Davis and Carter’s (2008) findings suggested that regulatory problems (e.g., eating, sleeping, emotion regulation) are associated with maternal stress, whereas children's externalizing behavior was associated with paternal stress. Moreover, the financial burden has been shown to be another important factor of distress in families with ASD children (Ilias et al., 2018; Liao & Li, 2020).

Besides these factors, there is evidence that social support, whether from a life partner, family, support groups, or professional services, can serve as a potential protective factor against parental stress (e.g., Drogomyretska et al., 2020; Ilias et al., 2018). In Hall and Graff’s study (2011) the life partner or spouse was chosen as the most helpful support system, while more current findings suggest that support derived from friends seems to be more important in protecting against parental stress (Drogomyretska et al., 2020). It needs to be stated that besides the external factors that protect against parental stress, there are certain internal factors too. Forgiveness (Oti-Boadi et al., 2020; Weinberg, et al., 2021) and self-compassion (Neff & Faso, 2014) are examples of internal factors that have proved promising in mitigating parental stress in parents of children with ASD. Later in this study, we take a closer, more detailed look at self-forgiveness as a potential protective factor, as thus far there has been only one study focusing specifically on self-forgiveness in parents of children with ASD (Melli et al., 2016). However, it did not consider guilt and shame experiences.

Guilt and Shame experiences of parents of children with ASD

Both guilt and shame are moral and self-conscious emotions involving negative self-evaluations and feelings of distress elicited by one’s perceived failures or transgressions (Tangney et al., 2007). The original distinction proposed by Lewis (1971) suggests that guilt focuses on the behavior, and shame on oneself. When individuals feel guilt, they experience tension, remorse, and regret over the “bad thing done”. On the other hand, when individuals feel shame, they feel diminished, worthless, and exposed. Feelings of shame often lead to a desire to escape or hide (Tangney et al., 2007). Research has shown that guilt typically motivates reparative action – confessing, apologizing, or repairing the damage done (Tangney et al., 2007). On the contrary, shame proneness (individual’s tendency to have feelings of shame) has been associated with avoidance tendencies (Schmader & Lickel, 2006) and psychopathological symptoms such as somatization, depression, anxiety, or hostility (Muris & Meesters, 2014). Interestingly, Scarnier et al. (2009) found that guilt predicted adaptive parenting responses (parents’ efforts to apologize and make up for damage caused by their child’s behavior), whereas shame predicted maladaptive ones (harsh punishment and the withholding of emotional warmth) in response to children’s wrongdoings. In this study, we focus on parents’ experiences of guilt and shame, not their proneness to these feelings.

Guilt and shame are also likely to be experienced by parents of NT children, but since the public often misunderstand the behavior of children with ASD, these experiences of guilt and shame probably differ in parents of NT children versus ASD children. Since feelings of guilt and shame can be very painful for parents, counselors and therapists seeking to improve their interventions may benefit from a more nuanced understanding of these feelings and experiences in these groups of parents. Moreover, we are going to use the Guilt and Shame Experience scale (Maliňáková et al., 2019), which consists of general scenarios relating to guilt and shame experiences (items may include parental themes as well as more general ones). There is no existing questionnaire focusing specifically on guilt and shame experiences related to parenting, so we are going to explore these experiences using a qualitative approach.

Some parents naturally experience feelings of guilt and shame alongside anger after the initial shock, denial, grief, or depression associated with the process of accepting their child’s diagnosis (Kocabıyık & Fazlıoğlu, 2018). Mothers often feel guilt because they believe that they caused their child's autism (Mercer et al., 2006). After the initial acceptance process (sometimes unfinished), parents have to cope with other difficulties in everyday life, and experience both positive and negative feelings.

Regarding the child's diagnosis and behavior, parents may encounter negative attitudes from other people and experience unpleasant feelings. Stigma is one of the most common external attitudes (Salleh et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2018) that can have a negative impact on parents’ mental health, since it involves labeling, stereotyping, separation, negative emotional reactions, and discrimination (Zhang et al., 2018). Other common feelings such as shame or embarrassment at the child's publicly inappropriate behavior and people's reactions to it are highly prevalent (Burrell et al., 2017; Ha et al., 2014). In China, shame proneness has also been found to predict affiliate stigma (parents’ internalization of others’ negative evaluations and emotions toward themselves and their children) in parents of children with ASD, and, together with low self-esteem and poor family adaptability, it is associated with depressive symptoms (Zhou et al., 2018). Parents may also experience feelings of guilt about not doing enough for their child with ASD, or in relation to other children they may have with neurotypical development (Kuhn & Carter, 2006). Guilt and shame may therefore be associated with anxiety, depression, and parental stress (Cappe et al., 2011; Ghoreishi et al., 2018).

Self-forgiveness

Self-forgiveness, like forgiving others, can be defined as replacing negative thoughts and feelings toward oneself with positive ones (Hall & Fincham, 2005; Worthington, 2013). Self-forgiveness has been found to positively relate to mental and physical health, as well as to life satisfaction (Macaskill, 2012). Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that self-forgiveness can be used to cope with the stressful effects of self-condemnation (Toussaint et al., 2017). Davis et al. (2015) also consider self-forgiveness to be an emotion-focused coping approach for dealing with stresses that result from personal failure, guilt, shame, or general incongruence between personal values and actual behavior. Previous research has indicated that self-forgiveness in mothers of children with mental retardation predicted a positive change in the mother–child interaction (Khosroshahi Jafar, 2017). Also, self-forgiveness in bereaved parents predicted their positive psychological adjustment (Záhorcová et al., 2020).

Research focusing on forgiveness in parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Nemati et al., 2016), as well as learning disabilities (Finardi et al., 2022), revealed a positive association between self-forgiveness and mental health and a negative association with psychological distress. In recent years, researchers have also focused on forgiveness in parents of children with ASD, showing that higher levels of forgiveness toward others were associated with lower levels of parental stress (Weinberg et al., 2021). A qualitative study by Oti-Boadi et al. (2020) revealed that forgiving others empowered Ghanaian mothers of children with ASD to handle their stigma and improve their health and relationships with others.

In light of these findings on the positive role of forgiveness in parents of children with ASD, we build on previous research by focusing specifically on self-forgiveness, which is considered a coping mechanism for dealing with stress in some previous studies (Davis et al., 2015; Toussaint et al., 2017). We also focus on guilt and shame experiences, since these are thought to be important emotional determinants of self-forgiveness (Hall & Fincham, 2005) and are relatively common in parents of children with ASD (Burrell et al., 2017; Ha et al., 2014; Mercer et al., 2006). Studies have also shown that working on self-forgiveness, e.g. through an intervention, can lead to a reduction in shame (e.g. Scherer et al., 2011). Since higher shame is related to higher levels of parental stress, including in mothers of children with ASD (Asai & Kameoka, 2005), we hypothesized that shame may mediate the relationship between self-forgiveness and parental stress. Thus far no study has focused specifically on this type of self-forgiveness and on guilt and shame in relation to parental stress in parents of children with ASD as against parents of NT children. Therefore, the aims of this study are to:

determine whether there is any difference in the level of self-forgiveness, shame, and guilt in parents of children with ASD compared to parents of NT children, assuming that parental stress is higher in parents of children with ASD;

investigate guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness (controlling for the child's age and time since diagnosis) as potential predictors of parental stress in parents of children with ASD, compared to parents of NT children;

focus on the potential mediation role of guilt and shame in the connection of parental stress and self-forgiveness;

understand the specific experiences parents have of guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness using qualitative analysis.

Methods

Procedure

A mixed-method approach, using a set of questionnaires and open-ended questions, was adopted to obtain a fuller understanding of guilt and shame experiences, such as the role of self-forgiveness and stress in parents of children with ASD and of neurotypical children. An online survey (including questionnaires and written open-ended questions) was distributed through the Internet and social networking sites (e.g., Facebook) to relevant groups—such as support groups for parents of ASD children, and generally for parents with NT children. Both groups received the same survey package; only the instructions differed for the two groups of parents. A snowball sampling method was used. Participation in the research was anonymous and voluntary. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. There was no compensation for participation.

Participants

Two groups of parents participated in the research. The criteria for participation in the group of parents of children with ASD were: the child had to be aged 3–18 and had to have been professionally diagnosed with ASD at least one year previously. In the group of parents with neurotypical children, there were two conditions – the child had to be within the same age range (3–18 years) and without an ASD diagnosis at the time of the study.

The final research sample consisted of 278 participants: 143 parents of children with ASD (51.4%) and 135 parents of NT children (48.6%). The age of the parents ranged from 22 to 61 years (M = 37.63, SD = 6.58); for parents of children with ASD: M = 39.07, SD = 5.78; for parents of NT children: M = 36.10, SD = 7.04. All participants were Slovak. The research group consisted of 24 men (8.63%), of which 10 were fathers of children with ASD and 14 were fathers of NT children, and 254 women (91.37%), of which 133 were mothers of children with ASD and 121 were mothers of NT children.

Most participants identified as married (70.5%) with 15.1% in a romantic relationship, 10.43% divorced, and 3.96% single. Participant education included: secondary school (n = 123), Master's (n = 107), Bachelor's (n = 23), Doctorate (n = 18), and lower secondary school (n = 7). Diagnosis of childhood autism was reported by 96 parents (67.13%), Asperger’s syndrome by 32 parents (22.38%), and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified by 15 parents (10.49%), and the mean time since ASD diagnosis was 4.26 years (SD = 3.00). The mean age of children with ASD was 8.45 (SD = 3.63), and mean age of NT children was 7.30 (SD = 4.45).

A post hoc power analysis using the program G*Power revealed that on the basis of the mean correlation coefficient observed in the present study (r = 0.79), with α = 0.05, an n of 143 (ASD group) was sufficient to obtain statistical power of 0.99 level. Subsequently, the post hoc power analysis revealed that on the basis of the mean correlation coefficient observed in the present study (r = 0.75), with α = 0.05, an n of 135 (NT group) was sufficient to obtain statistical power of 0.99 level.

Measures

The survey package included an informed consent form and demographic information about the parent and child (parent – sex, age, education, marital status; child – age, child’s diagnosis, and length of time since diagnosis). It also contained the questionnaires, which had been independently translated from English to Slovak and back to English, with the approval of the questionnaires’ authors.

The Guilt and Shame Experience Scale (GSES; Maliňáková et al., 2019) was used to assess guilt and shame experiences. It is a statement-based measure containing items describing the experience of guilt and shame in greater detail and context. To our knowledge, there is no measurement focusing specifically on guilt and shame parenting experiences, so we decided to use a more global measurement with good psychometric characteristics that has been validated on the Slovak population. It consists of eight items – four items on guilt e.g., (“When I do something wrong, I feel an exaggerated feeling of guilt”) and four items on shame e.g., (“I experience moments when I cannot even look at myself”). Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (significantly). Internal consistency of the guilt subscale was α = 0.82 (ASD), α = 0.74 (NT); for shame α = 0.82 (ASD), α = 0.83 (NT).

The Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS; Thompson et al., 2005) is a self-report measure of dispositional forgiveness (self, others, situations). To measure self-forgiveness, the tendency to forgive self subscale was used (α = 0.77 ASD, α = 0.67 NT). This subscale contains six items, e.g., (“With time I am understanding of myself for mistakes I’ve made”) and each item is scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always false of me) to 7 (almost always true of me).

The Parental Stress Scale (PSS; Berry & Jones, 1995) was used to assess parents’ feelings about their parenting role, exploring both positive aspects (e.g., emotional benefits) and negative aspects of parenthood (e.g., feelings of stress). The scale consists of 18 items, scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items are (“The major source of stress in my life is my child”) or (“I sometimes worry whether I am doing enough for my child”). Internal consistency was α = 0.89 (ASD); α = 0.84 (NT).

To obtain a fuller understanding, we also asked participants optional open-ended questions about guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness. The open-ended questions relating to guilt and shame (Q1, Q2) were included to explore any differences between the group of parents with children with ASD and the group with NT children. Moreover, we wanted to find out if there were any differences in shameful experiences regarding parenting in these two groups of parents (Q3), since there is some evidence that parents of children with ASD may experience more shame in relation to their child's behavior (Burrell et al., 2017; Ha et al., 2014). None of the previous studies has focused on self-forgiveness in parents of children with ASD (although Oti-Boadi et al., 2020 looked at forgiving others); therefore, our goal was to find out if parents felt the need to forgive themselves in regard to their parenting and if so to map the potential facilitators and barriers to this process (Q4). The following questions were asked:

“What is your understanding of the concept of guilt?”; 2) “What is your understanding of the concept of shame?”; 3) “Do you ever feel ashamed of your child's behavior? If so, what do you find most embarrassing about your child's behavior?”; 4) “Is there anything about your parenting that you feel you need to forgive yourself for? Or is there something you haven't forgiven yourself for?”; “If so, what helps or prevents you from forgiving yourself?”

Data analysis

Quantitative data was analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20.0., specifically correlational analysis, regression analysis, mediation analysis, and Mann–Whitney U-test.

The answers to the open-ended questions were analyzed using Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M; Hill & Knox, 2021), which allows for the analysis of simple qualitative data within a larger sample size. This method uses a bottom-up approach, where the results, i.e., categories and subcategories, emerge from the data without any theoretical concepts being imposed on the data. CQR-M has a team of judges who independently analyze the data in each step until a consensus is reached. In our case, the primary research team included the first and the third author of the study, who were both trained in this method by the second author who teaches a course in qualitative methodology at the university and has extensive experience in data analysis using CQR-M. Participants' written responses to open-ended questions were independently analyzed by team members, who first developed a set of domains (based on the open-ended questions) and then categorized the data into categories and subcategories. To ensure the validity of the method, the CQR-M consists of a series of steps, depending on the number of participants. Consistent with the recommendations of Hill and Knox (2021) and based on sample size (N = 278), our research required three steps. The judges independently analyzed data relating to around 92 participants in steps one, two, and three. After each judge had independently analyzed the 92 responses (i.e., created domains, categories, and subcategories), the team members thoroughly discussed the analysis until they reached a consensus. Then, the data was reviewed by the auditor to ensure its accuracy and validity. The auditor’s suggestions were incorporated into the analysis after each step. In the second step, another 92 responses were independently analyzed, discussed by the judges together and reviewed by the auditor. The same was done in the third step. The final categorization was obtained after the third judges meeting, the auditor’s final review, and the last discussion between all the research members where the consensus was reached. At the end, the team members selected a representative item for each category and subcategory.

Results

Quantitative results

Descriptive analyses of all variables (guilt, shame, self-forgiveness, and parental stress) are summarized in Table 1. As can be seen from correlational analyses in Table 2, for both groups of parents, there is a strong positive correlation between guilt and shame, and a strong negative correlation between self-forgiveness and shame, as well as self-forgiveness and guilt. Parental stress is very strongly positively related to guilt and shame in both groups of parents. Self-forgiveness is strongly negatively related to parental stress in both groups of parents.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of all variables

| parents of children with ASD (n = 143) |

parents of neurotypical children (n = 135) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| guilt | shame | self-forgiveness | parental stress | guilt | shame | self-forgiveness | parental stress | |

| M | 11.13 | 8.88 | 28.74 | 47.50 | 10.68 | 7.93 | 29.91 | 37.49 |

| SD | 3.35 | 3.35 | 5.72 | 12.36 | 3.28 | 2.73 | 4.72 | 8.95 |

Table 2.

Correlational analysis of all variables

| parents of children with ASD (n = 143) |

parents with neurotypical children (n = 135) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| guilt | shame | self-forgiveness | parental stress | guilt | shame | self-forgiveness | parental stress | |

| guilt | - | - | ||||||

| shame | .77** | - | .75** | - | ||||

|

self- forgiveness |

-.66** | -.72** | - | -.63** | -.58** | - | ||

| parental stress | .94** | .94** | -.73** | - | .95** | .92** | -.65** | - |

Bolded values represent significant results

** ≤ .01

Next, we tested for potential differences in parental stress, self-forgiveness, shame, and guilt between parents of children with ASD and parents of NT children. Given the normality tests did not show a normal data distribution for any of the above mentioned variables, we ran Mann–Whitney U-tests. As can be seen from Table 3, parental stress is significantly higher in parents of children with ASD (Mr = 172.46) than in parents of NT children (Mr = 104.59); U = 4939.50; p ≤ 0.001, there is a medium effect size r = 0.42. Table 3 also shows that shame is significantly higher in parents of ASD children (Mr = 149.98) than in parents of NT children (Mr = 128.40); U = 8154.50; p = 0.025, there is a small effect size r = 0.13. There was no significant difference in guilt and self-forgiveness between the two groups of parents (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Differences in parental stress, self-forgiveness, shame, and guilt in parents of children with ASD and in parents of neurotypical children

| Group | n | Mean rank | Z | U | p | r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental stress | 1 | 143 | 172.46 | -7.04 | 4939.50* | ≤ .001 | .42 |

| 2 | 135 | 104.59 | |||||

| Shame | 1 | 143 | 149.98 | -2.247 | 8154.50 | .025 | .13 |

| 2 | 135 | 128.40 | |||||

| Guilt | 1 | 143 | 144.94 | -1.166 | 8874.50 | .244 | .07 |

| 2 | 135 | 133.74 | |||||

|

Self- forgiveness |

1 | 143 | 130.05 | -1.924 | 8301.500 | .054 | .12 |

| 2 | 135 | 148.55 |

1 = parents of children with ASD, 2 = parents of neurotypical children

*one-side significance tests, all other tests are two-side significance tests

Bolded values represent significant results

In order to examine whether guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness predict parental stress in parents of children with ASD, over and above the child’s age and time since diagnosis, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. Child’s age and time since diagnosis were entered in Step 1, guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness were entered in Step 2. As can be seen in Table 4, the first model explained 4% of the variance in parental stress and only the child’s age acted as a significant negative predictor of parental stress. Adding guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness to the predictors increased the variance explained by the model by 23.2% and this change was statistically significant. In Model 2, the child’s age was no longer significant. Only self-forgiveness was a significant negative predictor of parental stress (β = -0.34).

Table 4.

Model summaries for hierarchical regression analysis of effect of child's age, time since diagnosis, guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness on parental stress

| Parents of children with ASD | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t | 95% CI | R | R2 | R2 change | F |

F Change |

Sig. of F change |

| Step 1 | .201 | .040 | .040 | 2.94 | 2.94 | .056 | |||||

| Child’s age | -.89 | .40 | -.26* | -2.24 | [-1.68, -.11] | .027 | |||||

| Time since diagnosis | -.45 | .48 | .10 | .93 | [-.50, 1.40] | .353 | |||||

| Step 2 | .273 | .232 | 10.27 | 14.59 | .000 | ||||||

| Child’s age | -.55 | .36 | -.16 | -1.53 | [-1.25, .16] | .127 | |||||

| Time since diagnosis | .41 | .43 | .10 | .97 | [-43, 1.26] | .336 | |||||

| Guilt | .05 | .43 | .01 | .11 | [-.81, .90] | .915 | |||||

| Shame | .65 | .47 | .17 | 1.39 | [-.28, 1.59] | .168 | |||||

| Self-forgiveness | -.73 | .23 | -.34** | -3.14 | [-1.19, -.27] | .002 | |||||

Bolded values represent significant results

** p ≤ .01; * p ≤ .05

In order to examine how guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness predict parental stress in parents of neurotypical children, a multiple regression analysis, ENTER method, was performed. Results can be seen in Table 5 and show that these variables explain 6.5% of the variance of parental stress in parents of neurotypical children, (F(3, 131) = 3.02, p = 0.032). As can be seen from Table 5, guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness are not significant predictors of parental stress in parents of neurotypical children.

Table 5.

Regression analysis of guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness as predictors of parental stress

| Parents of neurotypical children | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parental stress | B | SE B | β | t | p | 95% CI | |

| guilt | .21 | .37 | .11 | .56 | .577 | [-.53, .95] | |

| shame | .22 | .43 | .07 | .50 | .617 | [-.63, 1.06] | |

| self-forgiveness | -.28 | .21 | -.15 | -1.32 | .188 | [-.70, .14] | |

| R2 | .065 | ||||||

| F | 3.02 | ||||||

Next, we tested whether guilt/shame mediate the relationship between self-forgiveness and parental stress in parents of children with ASD and parents of neurotypical children. To test whether an indirect a*b effect occurred, we used the bootstrapping procedure to compute a confidence interval around the indirect effect. The indirect effect was tested using a bootstrap estimation approach with 10,000 samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). If the 95% confidence interval does not include a zero, then it is significant at 0.05. In parents of neurotypical children, the mediation of guilt or shame in the relationship between self-forgiveness and parental stress was not significant (p > 0.05). Also, there was no mediation of guilt in the relationship between self-forgiveness and parental stress in parents of children with ASD (p > 0.05).

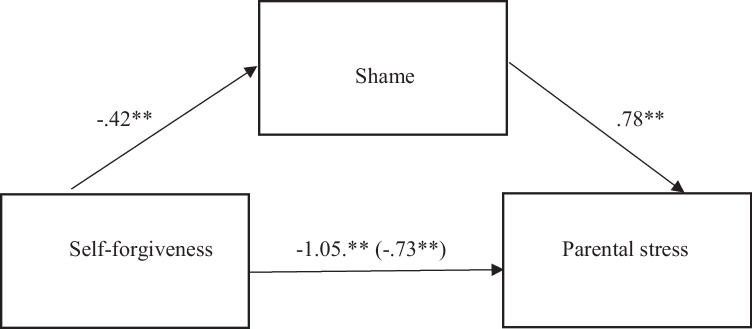

We found self-forgiveness had a significant indirect effect on parental stress through the mediation of shame in parents of children with ASD in, ab = -0.33, where the 95% confidence interval did not include a zero [95% Cl = -0.62; -0.04]. There was a medium effect size, Pm = 0.31. Self-forgiveness had a non-significant indirect effect on parental stress through the mediation of guilt in both groups of parents. Similarly, self-forgiveness had a non-significant indirect effect on parental stress through the mediation of shame in parents of neurotypical children. Figure 1 shows the mediation pathway.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized mediation model. Shame mediates the relationship between self-forgiveness and parental stress in parents of children with ASD

Qualitative results

Qualitative data on the open-ended questions were coded using CQR-M (Hill & Knox, 2021).

Understanding of guilt

In regard to parents' understanding of guilt, four main categories emerged in both groups of parents: a) subjective guilt, b) objective guilt, c) do not know, d) other. Summary of categories and subcategories can be seen in Table 6.

Table 6.

Categories and subcategories of guilt and shame understanding, and shame experiences in relation to parenting in both group of parents

| Parents of Children with ASD (n = 143) |

Parents of Neurotypical Children (n = 135) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CATEGORY | SUBCATEGORY | CATEGORY | SUBCATEGORY | |

| Understanding of Guilt |

Subjective Guilt |

Own Failure |

Subjective Guilt |

Own Failure |

| Self-blame | Transgression | |||

| Remorse |

Objective Guilt |

Responsibility | ||

|

Objective Guilt |

Did/Have done something bad |

Did/Have done something bad | ||

| Responsibility | Hurting Another Person | |||

| Other | Other | |||

| Understanding of Shame |

External Shame |

Condemned by Society |

External Shame |

Ashamed of Actions and Behavior |

|

Child’s Inappropriate Behavior |

Public Condemnation | |||

| Ashamed of Behavior | Embarrassing Situation | |||

| Embarrassing Situation | Child Behaving Inappropriately in Public | |||

| Other People’s Shame | ||||

|

Internal Shame |

Unpleasant Feelings |

Internal Shame |

Unpleasant Feelings | |

| Own Failure | Own Failure | |||

| Imperfection and the Failure to Fulfill Expectations |

Failure to Fulfil Society’s Expectations |

|||

| Desire to Escape | Humiliation | |||

| Failure to Handle the Situation | Wanting to Disappear | |||

| Failure to Handle the Situation | ||||

| Own Imperfection | ||||

| Did not feel ashamed | Other | |||

| Other | ||||

| Shameful Experiences in Parenting | Exogenous Factors | Child Behaving Inappropriately in Public | Exogenous factors | Child Behaving Inappropriately in Public |

| Public Condemnation/Misunderstanding | ||||

| Social Gatherings | ||||

| Don’t Feel Ashamed | Resignation | Did not Feel Ashamed | ||

| Don’t Feel Ashamed | ||||

| Endogenous Factors | Shame as their Own Failure | Endogenous factors | Own Failure | |

| Difficulty Communicating with the Child | ||||

| ASD Not Being Accepted by Close Family | ||||

In parents of children with ASD, the most frequent category was Subjective Guilt (68/143) which consisted of three subcategories: Own Failure (42/143) for not managing a certain situation, or as the result of a bad decision (P23, woman: “Feeling that my child was suffering the consequences of me not being able to do something”); Self-blame (16/143) was associated with long-term feelings of guilt and the inability to forgive oneself (P1, woman: “Guilt – blaming myself for everything, that I am to blame for the way the world turns”); and the subcategory Remorse (5/143) was associated with compunction. Objective Guilt category (62/143) consisted of two subcategories – Did/Have done something bad (43/143) e.g., P137, man: “an action which causes an inconvenience, accident or wrong decision” and Responsibility (19/143) in which responses were associated with taking responsibility for one’s actions and decisions. Some participants answered that they did not know (18/143); and the category Other (5/143) was created for the data in which parents described guilt as an unpleasant feeling, as being associated with painful feelings or anger at the child, etc.

In parents of NT children, Subjective Guilt (64/135) consisted of two subcategories: Own Failure (44/135) and Transgression (20/135). Both of these subcategories had one common characteristic – a focus on oneself. The Objective Guilt category (65/135) consisted of three subcategories: Did/Have done something bad (31/135), often associated with lying; Responsibility (23/135); and the subcategory Hurting Another Person (11/135), in which parents of NT children described feeling guilty immediately after hurting someone. Some of the participants’ answers (8/135) were included in the category do not know, and the rest (7/135) were included in the Other category (e.g., disappointment; feeling bad about oneself; unacceptable).

Understanding of shame

In both groups of parents, the same five categories of shame emerged: a) external shame, b) internal shame, c) do not know, d) do not feel ashamed, e) other, which can also be seen in Table 6.

In parents of children with ASD, the most frequent category was External Shame (87/143), which consisted of five subcategories: Condemned by Society (33/143) in which parents mentioned hostile glances from other people because of their child's behavior or misunderstandings (P33, man: “Feeling others’ contempt, condemnation”); Child’s Inappropriate Behavior (19/143) was associated mostly with the child screaming, behaving unpredictably or aggressively (P4, woman: “When my child screams and I can't calm him down, people watch and shake their heads”). Less frequent subcategories were Ashamed of Behavior (15/143) (P51, woman: “Worrying about something we’re doing”); Embarrassing Situation (15/143); and Other People’s Shame (5/143) e.g., P110, woman: “Certainly not that I am the mother of a child with a developmental ASD. Rude people who condemn everything and everyone without knowing their situation should be ashamed”. The category of Internal Shame (67/143) consisted of five subcategories: Unpleasant Feeling (21/143) (P29, man: “Feeling bad in a social situation.“); Own Failure (16/143) – P142, woman: “Feeling my own or others’ failure, that is exposed to other people's judgments”; Imperfection and the Failure to Fulfill Expectations (19/143) – P6, woman: “feeling of individuals’ imperfection about their actions, decisions or what they say…in any situation in which they don’t fulfill others’ expectations”; Desire to Escape (6/143) and Failure to Handle the Situation (5/143). To sum up, in the Internal Shame category, participants were focused on themselves, associated with the failure of their own actions, fulfilling their or others’ expectations. Some parents of children with ASD (14/143) said they did not feel ashamed to the extent they could describe it; some data fell under the Other category (14/143), such as humiliation, fear, stress, or harm. Twelve participants' answers were included in the category Don’t Know.

On the other hand, for parents of NT children, the most frequent category was Internal Shame (77/135) which contained seven subcategories: Unpleasant Feelings (23/135) e.g., P30, man: “When I am uncomfortable with something”; Own Failure (22/135) (P23, woman: "If my child gave any sign of me failing, e.g., in his care, it would be shameful for me"); Humiliation (10/135) (e.g., P96, woman: “A situation in which I feel uncomfortable or humiliated”); Failure to Fulfil Society’s Expectations (6/135) – P124, woman: “Being different from the majority”; Wanting to Disappear (6/135) (e.g., P48, woman: “A shameful situation in which you wish the ground would open up under you”); Failure to Handle the Situation (5/135); Own Imperfection (5/135) P107, woman: "Feelings of inadequacy, incompleteness". This category and its subcategories differed from that of parents of children with ASD, since the answers were not linked to their child or parenting. The category of External Shame (59/135) included the subcategories: Ashamed of Actions and Behavior (22/135) – P32, woman: “If someone feels uncomfortable in society about an act or behavior”; Public Condemnation (18/135) e.g., P3, woman: “when those around you condemn you”; Embarrassing Situation (12/135); Child Behaving Inappropriately in Public (7/135) e.g., P139, woman: "When I want my child to behave differently and I know that what he is doing is excessive …". In this group, some parents (19/135) did not know how to answer, and some answers were included in the Other category (13/135).

Shameful experiences in parenting

Furthermore, we focused on participants' most shameful experiences relating to parenting. In both groups three main categories emerged: a) exogenous factors, b) endogenous factors, c) do not feel ashamed. These categories and subcategories can be seen in Table 6.

In parents of children with ASD, the most frequent category was Exogenous Factors (95/143), often associated with Child Behaving Inappropriately in Public (63/143) – P36, woman: “Mostly, when he has a fit of anger in public and attracts attention to himself”; followed by Public Condemnation/Misunderstanding (29/143) – P10, woman: “fear of public reaction, misunderstanding” or generally attending Social Gatherings (3/143). Another relatively frequent category was Don’t Feel Ashamed (47/143), where parents often mentioned the subcategory Resignation (13/143) – P13, woman: “I experienced it for the first years, not now, I don't even feel the need to explain anything to anyone anymore”; and a relatively less frequent category was Endogenous Factors (7/143), in which parents described the subcategories: Shame as their Own Failure; Difficulty Communicating with the Child or ASD Not Being Accepted by Close Family.

Most parents of NT children did not feel ashamed (75/135), while those who did, claimed it was mostly due to the Child Behaving Inappropriately in Public (42/135, Exogenous factors) e.g., P44, woman: “Sometimes I'm ashamed of my daughter's audacity"; or Own Failure (11/135, Endogenous factors) e.g., P39, woman: “perhaps not exactly shame, but a mixture of sadness and failure”.

Self-forgiveness

Lastly, we focused on self-forgiveness, specifically whether parents felt the need to forgive themselves for something relating to parenting and if so, which factors help or prevent them from forgiving. The majority of the parents of children with ASD (78; 54.5%) gave reasons and situations in which self-forgiveness is relevant, while 10 (7%) participants did not know how to answer and 55 (38.5%) said they had nothing to forgive or did not need to forgive themselves. From those who mentioned reasons and situations, four main categories emerged: a) factors related to the parent, b) prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors, c) the need for self-forgiveness, d) other. Summary of individual categories and subcategories can be seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Categories and subcategories of self-forgiveness in relation to parenting, and its facilitators and barriers for both groups of parents

| Parents of Children with ASD (n = 143) |

Parents of Neurotypical Children (n = 135) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-forgiveness | CATEGORY | SUBCATEGORY | CATEGORY | SUBCATEGORY |

| Factors Related to the Parent | Parent Behaving Inappropriately Toward the Child | Factors Related to the Parent | Parent Behaving Inappropriately Toward the Child | |

| Parenting Practices | Parenting Practices | |||

| Own Person | Self-forgiveness to Themselves | |||

| Prenatal, Perinatal, and Postnatal Factors | Mother’s Behavior during Pregnancy | Factors Related to the Child | Insufficiently Close Attachment with | |

| Vaccination | Early Separation from the Child | |||

| Birth | ||||

| Need for Self-forgiveness | Something to forgive but not specified | |||

| Other | Irreversibility of ASD | Other | Not Providing the Ideal Family | |

| Financial Stability | Family’s Financial Stability | |||

| Facilitators | SUBCATEGORY | SUBCATEGORY | ||

| Acceptance | Acceptance | |||

| Social Support | Corrective Behavior | |||

| Religious Belief | Hope | |||

| Love from the Child | Child’s Progress | |||

| Corrective Behavior | Religious Belief | |||

| Rationalization | Social Support | |||

| Time | Forgiveness from Others | |||

| Other | Other | |||

| Barriers | Individual Characteristics | Individual Characteristics | ||

| Past | Inability to Change the Situation | |||

| Feelings of Guilt | Guilty Feelings | |||

| Exhaustion/Fatigue | Repeating the Same Mistakes | |||

| Other | Other | |||

Factors Related to the Parent (60/143) consisted of four subcategories, in which the most prevalent subcategory was Parent Behaving Inappropriately Toward the Child (23/143) (e.g., P88, woman: “I sometimes say bad words to my son”; followed by Parenting Practices (20/143) (e.g., P33, woman: “for lots of things, to provide more therapy, more attention, to learn more with my kid”; and Own Person (17/143), which often concerned psychological aspects (such as bad thoughts, imperfection, perfectionism) relating to the parent and parenting (e.g., P118, woman: “I forgive myself for feeling that I no longer dare to have another child, because I am not ready for the same situation (child’s autism) occurring again”). The Prenatal, Perinatal, and Postnatal Factors category (12/143) consisted of three subcategories, in which most answers were associated with Mother’s Behavior during Pregnancy (7/143) (e.g., P42, woman: “Yes, that I didn't take more vitamins during the pregnancy to keep my baby healthy”); following Vaccination (3/143) (e.g., P51, woman: “Yes, I should have read more about vaccinations and not have allowed my child to be vaccinated”); and Birth (2/143) (e.g., P6, woman: “Ideal childbirth and postpartum adaptation of the newborn… I should have organized it better”). Participants also described the Need for Self-forgiveness (11/143), e.g., P19, woman: “I forgave myself. I could see that I had made mistakes. And sometimes I need to forgive and accept forgiveness, …. I am increasingly aware of the need for daily forgiveness”. And the Other category (6/143) included the subcategory Irreversibility of ASD (5/143): most responses were about the irreversibility of the disorder and its consequences for the child’s future (e.g., P127, woman: “Bringing my child into such a society is unforgivable. When you know he doesn't have anyone and when you're not there, he'll be bullied and stuck in a care home”); and the subcategory of Financial Stability (1/143) (e.g., P11, man: “I can't help my child, we didn't have the money to put my child in kindergarten earlier”).

Additionally, two categories of factors helping or preventing self-forgiveness in parents of children with ASD emerged: a) facilitators and b) barriers, which can also be seen in Table 7.

The Facilitators category (61/143) consisted of eight subcategories: the most prevalent were Acceptance (12/143) – P26, woman: “I think about the fact that I am also a human being and sometimes I am exhausted” and Social Support (9/143) P45, woman: “My healthy daughter and husband help me”. Other categories were Religious Belief (8/143) where the answers mainly included faith, prayer, and confession; Love from the Child (8/143) e.g., P105, woman: “Huge love from her”; Corrective Behavior (7/143) e.g., P16, man: “I'm trying to fix those things”; Rationalization (5/143) P33, man: “a straight, clear and mainly a rational mind”; and Time (5/143) P20, woman: “Forgetting”. Some responses were included in the Other subcategory (7/143), such as psychological help, self-worth, apology, relaxation, or venting emotions. The Barriers category (28/143) consisted of five subcategories, of which the most frequently described were Individual Characteristics (7/143) in which the responses mainly related to parents’ temperament or character traits, (e.g., P4, woman: “My nature prevents me from forgiving myself” and Past (7/143) e.g., P79, woman: “That I can't take it back and change it”). Other subcategories were Feelings of Guilt (4/143) (e.g., P30, woman: “Guilty feelings and a bad conscience, which eats me up inside”); Exhaustion/Fatigue (3/143) e.g., P108, woman: “My lack of motivation prevents me from forgiving myself, I am already a burnt-out parent”; and the Other subcategory (7/143) which included answers concerning barriers such as social conventions, lack of family support, helplessness, or doubts. Some of the parents (54/143) said there was nothing that helped or prevented them from forgiving, and the rest (8/143) did not answer or did not know.

In the group of parents with NT children, 47% (63) said they had nothing to forgive or did not need to forgive themselves; 44% (60) mentioned reasons and situations in which self-forgiveness was relevant, and 12 (9%) did not know how to answer or did not answer. From those who mentioned reasons and situations, three main categories emerged: a) factors related to the parent, b) factors related to the child, c) other, which can be seen in Table 7.

In the category Factors Related to the Parent (44/135) similar subcategories to those found among parents of children with ASD emerged, with the most prevalent subcategory being Parent Behaving Inappropriately Toward the Child (screaming and failure to manage the situation) (21/135), in which parents often described their uncontrolled behavior toward the child, e.g., P33, woman: “My occasional and sometimes exaggerated outbursts of anger because of my daughter's behavior”. The second most common subcategory was Parenting Practices (16/135) P50, woman: “That I didn't teach her to eat more healthily”; and some participants (7/135) related self-forgiveness to Themselves (e.g., P84, woman: “I am too demanding of myself, and sometimes I blame myself for not doing enough for my child”). Factors Related to the Child (6/135) consisted of two subcategories – Insufficiently Close Attachment with Child (3/135) (e.g., P44, woman: “…I love him infinitely, I would give my life for him, but I feel that there is "a gap" between us. If it doesn't improve and it affects his life in the future, then yes, I will feel the need to forgive myself…”) and Early Separation from the Child (3/135) e.g., P39, woman: “That I had to go out to work too early”. Then there were some answers included in the Other (6/135) category, where participants described aspects related to Not Providing the Ideal Family (4/135) (e.g., P83, woman: “That my child is being raised by a non-biological father”), and some (2/135) related to the Family’s Financial Stability (e.g., P48, woman: “Yes. I try to forgive myself for repaying a large loan … we miss the money now, it could go to our daughter”). The rest of the participants (10/135) said that there was something to forgive but did not specify what.

Lastly, there were two categories of factors helping or preventing self-forgiveness in parents of NT children: a) facilitators, and b) barriers.

The Facilitators category (50/135) consisted of eight subcategories; the most frequent were Acceptance (13/135) – P28, woman: “knowing that I am also just learning to be a parent” and Corrective Behavior (9/135) e.g., P78, woman: “Going through a similar situation and solving it differently. Other categories were Hope (5/135) e.g., P42, woman: “that…it will be better”; Child’s Progress (5/135) where parents described some activities in which their child was progressing and said that helped e.g., P102, woman: “knowing that he is able to cope with things alone, that helps me”; Religious Belief (4/135), Social Support (3/135), and Forgiveness from Others (3/135) e.g., P61, woman: “It helps me when my children forgive me, I always try to explain to them that we are all human and we make mistakes,…”. Some answers came under the Other subcategory (8/135) such as – time, rationalization, child’s love, or communication. Barriers (22/135) consisted of six subcategories and, like in the first group of parents, the most frequent was Individual Characteristics (6/135), e.g., P16, woman: “….my own personality prevents me from forgiving, and that I won't be different”; and Inability to Change the Situation (5/135) where participants stated that they could not take the situation back. Less frequent barriers were Guilty Feelings (2/135) and Repeating the Same Mistakes (2). In the Other subcategory (7/135) were barriers such as health, tiredness, fear, or the child’s behavior. Some of the parents (47/135) said there was nothing which helped or prevented them from forgiving, three did not know how to answer, and the rest (23/135) did not answer.

Discussion

Using a mixed-method approach, this study aimed to compare self-forgiveness, guilt, shame, and parental stress in parents of children with ASD and parents of neurotypical children.

The results of the correlational analysis showed that shame and guilt are negatively related to self-forgiveness in both groups of parents. These findings regarding the negative association between shame and self-forgiveness are consistent with previous studies (McGaffin et al., 2013; Rangganadhan & Todorov, 2010) suggesting that parents with higher levels of shame tend to forgive themselves less. This result can be explained by the fact that shame involves an excessive and critical focus on oneself, associated with self-destructive intentions, which is the opposite of what is involved in self-forgiveness. In the self-forgiving process, individuals stop being critical and cultivate a compassionate attitude toward themselves (Enright, 2015). Our finding that guilt is negatively correlated with self-forgiveness in both groups of parents is consistent with some studies (Hall & Fincham, 2005), but contrary to those which found a positive association (McGaffin et al., 2013). One of the explanations for this finding is that individuals who feel guilt experience some combination of remorse, tension, or regret over their transgression, and these strong emotional responses can prevent them from forgiving themselves for an offense. But, given the correlational nature of this finding, an alternative explanation is that the ability to forgive oneself reduces the guilt, as well as the shame.

In addition, we found that as guilt and shame increased, parental stress increased in both groups of parents. This is not surprising, since those moral emotions involve a whole spectrum of negative experiences (e.g., critical focus, destructive intentions, remorse, regret—as was shown in the qualitative results of our study), and therefore can be naturally associated with increased levels of stress. The results also supported previous findings (Giovagnoli et al., 2015; Polónyiová et al., 2022) showing that parents of children with ASD showed higher levels of parental stress than parents of NT children.

The demonstrated negative association between self-forgiveness and parental stress indicates that individuals who cannot forgive themselves experience higher levels of parental stress, or alternatively those who experience lower levels of parental stress forgive themselves more easily. Nevertheless, self-forgiveness has already been hypothesized as a potential mechanism for coping with stressful events (Davis et al., 2015; Toussaint et al., 2017), and shows promise in relation to many other aspects of healthy functioning (Finardi et al., 2022; Macaskill, 2012). These findings were supported by the results of hierarchical regression analysis, which showed that guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness (controlling for child's age and time since diagnosis) explained 23.2% of the variance in parental stress in parents of children with ASD, while the only negative predictor was self-forgiveness. On the other hand, the results of the regression analysis showed that guilt, shame, and self-forgiveness are not significant predictors of parental stress in parents of neurotypical children. Thus, these results supported and expanded findings concerning the potential benefits of forgiveness in parents of children with ASD (Oti-Boadi et al., 2020; Weinberg et al., 2021), and the findings of Melli et al. (2016) that there is a negative association between self-forgiveness and parental stress. Moreover, it was found that shame (but not guilt) mediates self-forgiveness and the link with parental stress in parents of children with ASD only. Therefore, we can not only emphasize the importance of self-forgiveness as a potential coping mechanism for dealing with parental stress, but we can also assume that attention should be paid to shame as a relevant factor associated with self-forgiveness and parental stress in parents of children with ASD.

The quantitative results did not show a difference in guilt between the two groups of parents, whereas the qualitative results provided a more detailed understanding of guilt. Both groups of parents described guilt either in subjective terms (mainly in relation to their own failure, self-blame, remorse) or objective terms (doing something bad, hurting another person, or responsibility in general). It seems that parents of children with ASD are prone to subjective guilt, which is mainly associated with their failures, remorse, or self-blame. We assume this could be due to the many parenting difficulties associated with raising children with ASD. Guilt experiences were also associated with mothers blaming themselves for causing ASD or their inability to help their child. This finding is similar to findings by Mercer et al. (2006), who pointed out that parents of children with ASD often feel guilty for having caused their child’s disorder. On the other hand, parents of NT children described guilt as their own failure toward another person, rather than as self-blame or remorse. However, we did not notice any differences between both groups of parents in their responses concerning objective guilt.

We also found that parents of children with ASD experience more shame than parents of NT children, which is understandable, given the high potential of their child behaving inappropriately in public or people's misunderstanding and their reactions to it (Burrell et al., 2017; Ha et al., 2014). This finding was supported by qualitative ones that show that parents of children with ASD were more likely to describe external shame (condemnation from others), while parents of NT children were more likely to experience internal shame (negative feelings toward themselves). We assume this is a consequence of them being confronted with negative feedback from society about their child's behavior. Internal shame experiences were described similarly in both groups of parents and concerned unpleasant feelings, their own failure, imperfection, or humiliation. Additionally, in the ASD group, the responses were more likely to be linked to the parenting or the child, while in the NT group they were mainly linked to themselves.

Furthermore, there were some differences between both groups of parents’ descriptions of their shameful experiences. Specifically, parents of children with ASD mostly experienced shame in regard to their child’s inappropriate behavior or it being misunderstood by society, while parents of NT children mostly did not feel ashamed of their parenting. Moreover, differences were also detected in responses regarding the “Child’s Inappropriate Behavior”, with parents of children with ASD considering inappropriate behaviors to be screaming, aggressive and sexual behavior, etc., while parents of NT children tended to talk about the “children's honesty” when the child said something inappropriate or rude in public. These emotional and behavioral displays in children with ASD can be very challenging and shameful for most parents (Dababnah & Perish, 2013; Ha et al., 2014). Moreover, previous research found shame was associated with affiliate stigma and depressive symptoms in parents of children with ASD (Zhou et al., 2018), and it may, therefore, be naturally associated with increased levels of parental stress.

While the quantitative findings showed no differences in self-forgiveness between parents with ASD children and parents with NT children, the qualitative ones pointed to some similarities and differences regarding the need for self-forgiveness. Both the group of parents of children with ASD and the parents of NT children said they needed to forgive themselves mainly because of having behaved inappropriately toward their child, parenting practices, or their own negative feelings concerning parenting. Interestingly, parents of children with ASD also mentioned their behavior during pregnancy, the child’s birth, and vaccination (some parents believed that it may have caused their child's ASD), while parents of NT children were more likely to mention early separation from the child (having to go out to work) or being insufficiently closely attached to their child. Additionally, both groups of parents said that when they forgive themselves, acceptance is one of the most helpful factors. Parents of children with ASD also mentioned social support to some degree, which was previously noted by Drogomyretska et al. (2020). Both groups of parents mentioned religious belief, corrective behavior, rationalization, or the child’s progress. Both groups of parents agreed that individual characteristics are one of the most relevant factors in preventing self-forgiveness, while other subcategories were the past, inability to change the situation, exhaustion, or guilt feelings.

We are aware that our research findings need to be interpreted in the light of some limitations. Most of the participants in our sample were mothers – in both groups of parents. In the future, a more equal gender representation would allow for broader generalization. We did not obtain data about the severity of the children’s ASD symptomatology, but as this variable can be associated with parental stress, it should be considered in future studies. Also, criteria for the parents of the neurotypical children were that the children had to be 3–18 years old and have no ASD diagnosis at the time of the study. However, we did not ask about other diagnoses, such as mood disorders or ADHD, or other indicators, such as the number of children, which might have affected the results. Further, we used self-assessment scales so the participants could have given socially desirable answers. Moreover, the GSES measure is not primarily intended to measure parents’ experiences of guilt and shame. Therefore, the research in this area may benefit from the creation of a questionnaire focused specifically on parents' guilt and shame experiences. The qualitative questions were optional, and some participants did not answer them, which meant we had less data to analyze. Nor did we have the opportunity to ask additional questions to better understand the participants’ answers.

Conclusion

The individual relationships among the variables – expanded on and confirmed by the regression and mediation analysis model – indicate the importance of self-forgiveness as a potential coping mechanism for parental stress and the mediating role of shame, but only in parents of children with ASD. Counselors and therapists could help clients cope with parental stress through the use of techniques to foster self-forgiveness (e.g., REACH model—Scherer et al., 2011; Worthington, 2020) and minimize feelings of shame (e.g., Dearing & Tangney, 2011). In addition, the qualitative findings showed that parents of children with ASD experienced more subjective guilt and external shame, and more frequently found themselves in shameful situations because of their child’s inappropriate behavior or being misunderstood by society. Therefore, helping professionals could accompany parents of children with ASD in building resources that our participants found helped them with self-forgiveness. These were especially accepting one’s mistakes and failures and making use of resources such as social support or religious beliefs.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by “Vedecká grantová agentúra MŠVVaS a SAV” under contract number 1/0518/20.

Author Contributions

LZ, KL designed the study and collected data. DM, LZ, and KL were involved in data analysis. DM and LZ drafted the manuscript. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams D, Clark M, Simpson K. The Relationship Between Child Anxiety and the Quality of Life of Children, and Parents of Children, on the Autism Spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;50:1756–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03932-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Farsi OA, Al-Farsi YM, Al-Sharbati MM, Al-Adawi S. Stress, anxiety, and depression among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in Oman: A case-control study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2016;12:1943–1951. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S107103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asai MO, Kameoka VA. The influence of Sekentei on family caregiving and underutilization of social services among Japanese caregivers. Social Work. 2005;50(2):111–118. doi: 10.1093/sw/50.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JO, Jones WH. The Parental Stress Scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1995;12(3):463–472. doi: 10.1177/0265407595123009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell A, Ives J, Unwin G. The Experiences of Fathers Who Have Offspring with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(4):1135–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappe, E., Wolff, M., Bobet, R., & Adrien, J. (2011). Quality of life: a key variable to consider in the evaluation of adjustment in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and in the development of relevant support and assistance programmes. Quality of Life Research. An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 20(8), 1279–1294. 10.1007/s11136-011-9861-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dababnah S, Parish SL. “At a moment, you could collapse”: Raising children with autism in the West Bank. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(10):1670–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D. E., Ho, M. Y., Griffin, B. J., Bell, C., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., … Westbrook, C. J. (2015). Forgiving the self and physical and mental health correlates: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 329–335. 10.1037/cou0000063 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davis NO, Carter AS. Parenting Stress in Mothers and Fathers of Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Associations with Child Characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(7):1278–1291. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing RL, Tangney JP. Shame in the therapy hour. APA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Derguy C, M’Bailara K, Michel G, Roux S, Bouvard M. The Need for an Ecological Approach to Parental Stress in Autism Spectrum Disorders: The Combined Role of Individual and Environmental Factors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(6):1895–1905. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2719-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drogomyretska, K., Fox, R., & Colbert, D. (2020). Brief Report: Stress and Perceived Social Support in Parents of Children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 4176–4182 (2020). 10.1007/s10803-020-04455-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Enright, R. D. (2015). 8 Keys to Forgiveness. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Faras H, Al Ateeqi N, Tidmarsh L. Autism spectrum disorders. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2010;30(4):295–300. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.65261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finardi G, Paleari FG, Fincham FD. Parenting a Child with Learning Disabilities: Mothers’ Self-Forgiveness, Well-Being, and Parental Behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2022;31:2454–2471. doi: 10.1007/s10826-022-02395-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreishi MK, Hassan A, Hosseini KA. Structured Pattern for Parental Stress Based on Self-Conscious Affect and Family Performance of Children With Autism. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation. 2018;12(3):201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli G, Postorino V, Fatta LM, Sanges V, De Peppo L, Vassena L, De Rose P, Vicari S, Mazzone L. Behavioral and emotional profile and parental stress in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2015;45–46:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha VS, Whittaker A, Whittaker M, Rodger S. Living with autism spectrum disorder in Hanoi Vietnam. Social Sciences & Medicine. 2014;120:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HR, Graff JC. The Relationships Among Adaptive Behaviors of Children with Autism, Family Support, Parenting Stress, and Coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2011;34(1):4–25. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2011.555270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JH, Fincham FD. Self-forgiveness: The stepchild of forgiveness research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(5):621–637. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.5.621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(3):629–642. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Knox S. Essentials of Consensual Qualitative Research. American Psychological Association; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ilias, K., Cornish, K., Kummar, A. S., Park, M. S.-A., & Golden, K. J. (2018). Parenting Stress and Resilience in Parents of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Southeast Asia: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khosroshahi Jafar B. Communication Parental Self-Efficacy And Self Forgiveness With Mother-Child Interaction In Mothers Of Children With Mental Retardation. Journal of Exceptional Children Empowerment. 2017;8(22):26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kocabıyık, O. O., & Fazlıoğlu, Y. (2018). Life Stories of Parents with Autistic Children. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(3) 10.11114/jets.v6i3.2920

- Kuhn JC, Carter AS. Maternal self-efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:564–575. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB. Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review. 1971;58(3):419–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao X, Li Y. Economic burdens on parents of children with autism: A literature review. CNS Spectrums. 2020;25(4):468–474. doi: 10.1017/S1092852919001512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow A, Skelly C, Rohleder P. Challenges faced by parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(5):702–711. doi: 10.1177/1359105311422955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaskill A. Differentiating Dispositional Self-Forgiveness from Other-Forgiveness: Associations with Mental Health and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2012;31(1):28–50. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2012.31.1.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maliňáková K, Černá A, Fürstová J, Čermák I, Trnka R, Tavel P. Psychometric analysis of the guilt and shame experience scale (GSES) Československá Psychologie. 2019;63(2):177–192. [Google Scholar]

- McGaffin B, Lyons G, Deane FP. Self-forgiveness, shame and guilt in recovery from drug and alcohol problems. Substance Abuse. 2013;34(4):396–404. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.781564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melli, S., Grossi, E., C.Z., & A.C. (2016). Mental stress in parents and siblings of autistic children: review of the literature and original study of the related psychological dimensions. In A. Compare, C. Elia, A. G. Simonelli, & E.T.A.L. (Eds.), Psychological Distress (pp. 129–152). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Mercer L, Creighton S, Holden JJ, Lewis ME. Parental perspectives on the causes of an autism spectrum disorder in their children. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2006;15(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-9002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, A., Mira, A., Berenguer, C., Rosello, B., & Baixauli, I. (2019). Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children With Autism Without Intellectual Disability. Mediation of Behavioral Problems and Coping Strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(464). 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muris P, Meesters C. Small or big in the eyes of the other: On the developmental psychopathology of self-conscious emotions as shame, guilt, and pride. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2014;17(1):19–40. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0137-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Faso DJ. Self-Compassion and Well-Being in Parents of Children with Autism. Mindfulness. 2014;6(4):938–947. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0359-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, S., Mirnasab, M. M., Bonab, B. G. (2016).The Relationship between Dimensions of Forgiveness with Mental Health in Mothers of Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(4). 10.5539/jel.v5n4p15

- Oti-Boadi M, Dankyi E, Kwakye-Nuako CO. Stigma and Forgiveness in Ghanaian Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;50:1391–1400. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polónyiová, K., Rašková, B., & Ostatníková, D. (2022). Changes in Mental Health during Three Waves of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Slovakia: Neurotypical Children versus Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Parents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 10.3390/ijerph191911849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangganadhan AR, Todorov N. Personality and self-forgiveness: The roles of shame, guilt, empathy and conciliatory behavior. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(1):1–22. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salleh NS, Abdullah KL, Yoong TL, Jayanath S, Husain M. Parents’ experiences of affiliate stigma when caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2020;55:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarnier M, Schmader T, Lickel B. Parental shame and guilt: Distinguishing emotional responses to a child’s wrongdoings. Personal Relationships. 2009;16(2):205–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01219.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer M, Worthington EL, Hook JN, Campana KL. Forgiveness and the bottle: Promoting self-forgiveness in individuals who abuse alcohol. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2011;30(4):382–395. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2011.609804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Lickel B. The approach and avoidance function of guilt and shame emotions: Comparing reactions to self-caused and other-caused wrongdoing. Motivation and Emotion. 2006;30:43–56. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ. Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58(1):345–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.0911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LY, Snyder CR, Hoffman L, Michael ST, Rasmussen HN, Billings LS, Heinze L, Neufeld JE, Shorey HS, Roberts JC, Roberts DE. Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:313–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, L. L., Webb, J. R., & Hirsch, J. K. (2017). Self-Forgiveness and Health: A Stress-and-Coping Model. In Woodyatt, L., et al. (Eds.). Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness, 87–99. 10.1007/978-3-319-60573-9_7

- Walton KM. Leisure time and family functioning in families living with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2019;23(6):1384–1397. doi: 10.1177/1362361318812434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]