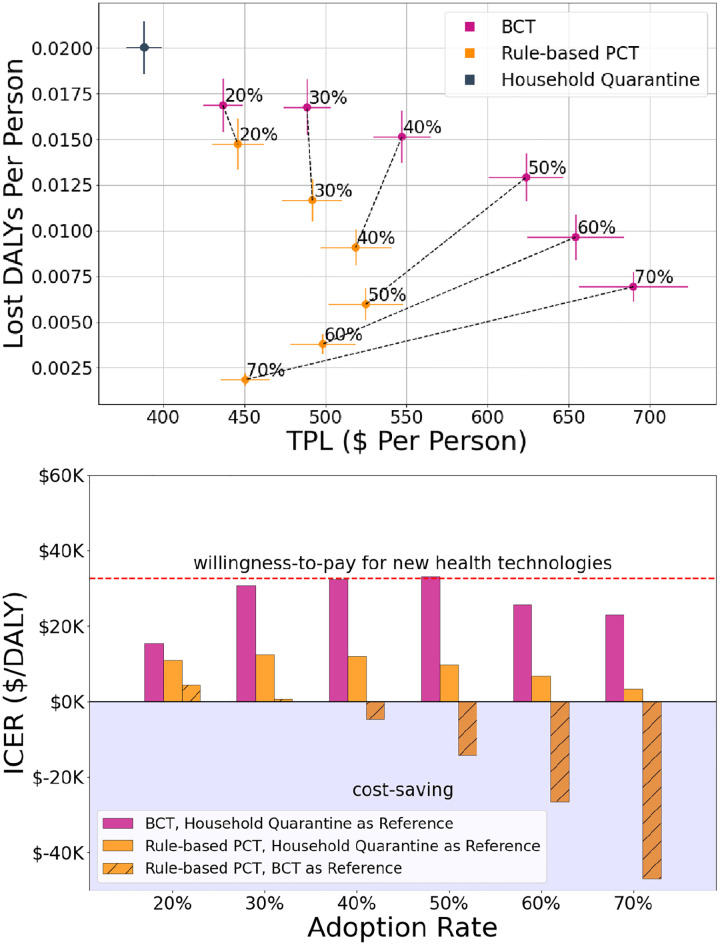

Fig 7. Cost-effectiveness analysis.

(a) We evaluate the trade-off between temporary productivity loss (TPL) per person and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per person for each of the scenarios (HQ, BCT, PCT) at various adoption rates (annotations). (b) Further, we compute incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) of BCT (pink bars) and PCT (yellow bars) with respect to HQ (unshaded bars) and of PCT with respect to BCT (shaded bars) to quantify these trade-offs with a single metric. The dashed red line represents a willingness-to-pay threshold for new health technologies [33] of $33K in 2020 Canadian dollars (see S5 Appendix for calculations). Gist Increased adoption rates lead to better health outcomes for both BCT and PCT, with PCT performing better than BCT across all adoption rates. Additionally, above 30% adoption, PCT is able to leverage the additional information to dominate BCT, making PCT cost-saving with respect to BCT in this regime. This pareto dominance of PCT over BCT above 30% adoption is shown in figure (b) by negative ICER values of PCT with BCT as a reference intervention (shaded bar). Across all adoption rates, the ICER of PCT is well below the willingness-to-pay threshold for new health technologies. As a final note, increases in the adoption rate of PCT above 50% lead to increasingly cost-saving outcomes.