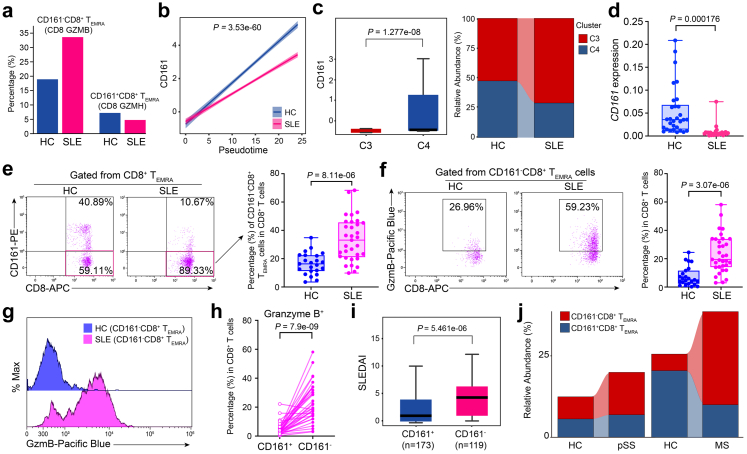

Fig. 4.

Expansion of CD161−CD8+TEMRAcells in SLE. (a) Percentages of CD161−CD8+ TEMRA and CD161+CD8+ TEMRA cell subclusters in HCs and SLE samples. (b) Two-dimensional plots showing the changes of CD161 expression over pseudotime in HCs and SLE samples. P value is calculated by Spearman correlation. (c) CD161 expression in CD161−CD8+ TEMRA and CD161+CD8+ TEMRA cell subcluster (left), and relative abundance of these two subsets in HCs and SLE subjects from public dataset (GSE162577) (right). P value is calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (d) CD161 expression of PBMCs from a new case–control cohort (HCs, n = 30; SLEs, n = 25). P value is from Unpaired t-test (e and f) Flow cytometry (left) and quantification (right) of the frequency of CD161−CD8+ TEMRA cells (e) cytoplastic levels granzyme B of CD161−CD8+ TEMRA (f) from a validation cohort (HCs, n = 23; SLEs, n = 33). P value is from Unpaired t-test. (g) Representative histogram showing granzyme B expression in HC and SLE samples. (h) Comparison of granzyme B expression in CD161−CD8+ TEMRA and CD161+CD8+ TEMRA cells from SLE samples (n = 33). P value is from Paired t-test. (i) Boxplot showing SLEDAI scores of SLE patients with high levels of CD161 and low levels of CD161 from public dataset (GSE121239). P value is calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (j) Sankey plot representing the relative abundance of CD161−CD8+ TEMRA cells and CD161+CD8+ TEMRA cells from case–control cohorts of pSS (left, GSE177278) and MS (right, GSE193770).