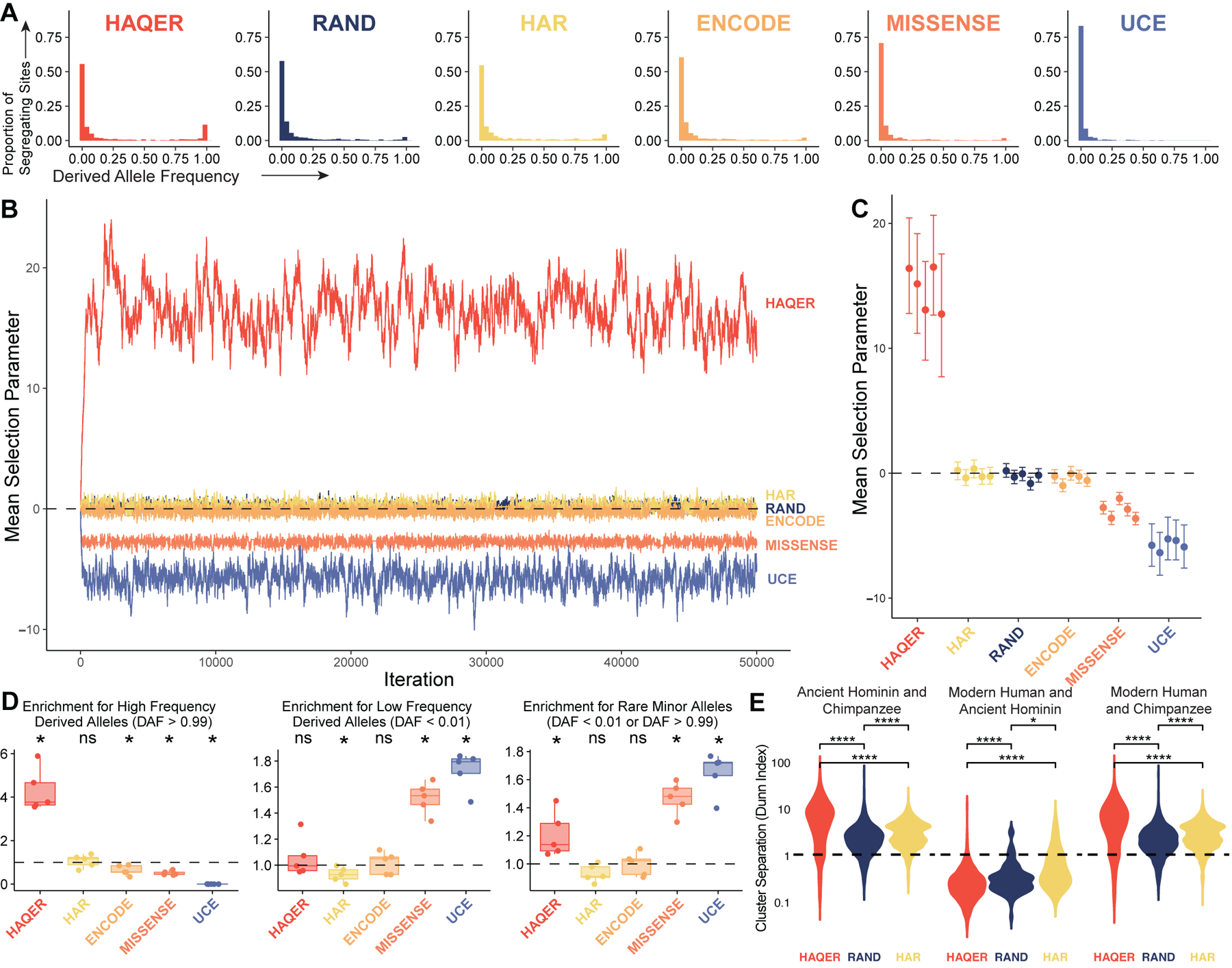

Figure 2: HAQER sequence divergence was driven by positive selection prior to the human-Neanderthal split.

(A) Derived allele frequency spectra representing 501 individuals from African populations (1002 alleles) for segregating sites within HAQERs, RAND, HARs, ENCODE candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs), missense variants (MISSENSE), or ultraconserved elements (UCEs). (B) Representative MCMC trace for the mean selection parameter acting on segregating sites within each set of regions. (C) Posterior mean and 95% highest density credible intervals describing the mean selection parameters for each set of regions inferred from segregating sites from five independent populations of unrelated African individuals. (D) Enrichment for high derived allele frequency (DAF > 0.99, left), low frequency (DAF < 0.01, center), and rare minor allele (DAF < 0.01 or DAF > 0.99, right) segregating sites relative to RAND (*: p < 0.05, Bonferroni-adjusted Mann-Whitney U). Each point represents the enrichment for one population of individuals partitioned from the set of all African individuals. (E) Distribution of the cluster separation (measured as the Dunn Index) between Ancient Hominins and Chimpanzees (left), Modern Humans and Ancient Hominins (center), or Modern Humans and Chimpanzees (right). Comparisons are presented between HAQERs, RAND, and HARs (Bonferroni-adjusted Mann-Whitney U, *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ****: p < 0.0001). See also Figures S3.