Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer survivors experience significant burden from comorbid chronic conditions, but little is known about how well these conditions are managed. We conducted a national survey of Australian breast cancer survivors to examine the burden of chronic conditions, their impact and care alignment with the principles of chronic condition management.

Methods

A study-specific survey incorporated questions about chronic conditions using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), functional status using the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES) and perceived quality of care for cancer and non-cancer conditions using the Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions Survey (PACIC). Members of Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA) were invited via email to complete the survey either online or through direct mail.

Results

The survey was sent to 2198 BCNA members and 177 responses were received (8.1%). Respondents were women aged 32–88 years (median 60.1 years). The majority were married (116; 67.7%) and had private insurance (137; 80.0%) and reported good to excellent health (119; 73.5%). Other health conditions were reported by 157 (88.7%), the most common being chronic pain (27.1%) and fatigue (22.0%). When asked about management of comorbidities or cancer, less than 20% were routinely asked about management goals, helped to set goals or asked about health habits.

Conclusions

In this population of survivors with good health status and high rates of private insurance, comorbidities were common and their management, as well as management of breast cancer, was poorly aligned with chronic condition management principles.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-023-07678-7.

Keywords: Chronic disease, Comorbidity, Breast cancer

Introduction

Comorbidities are common in patients with breast cancer, especially those who are older, because of their increasing prevalence with advancing age and shared risk factors for cancer and many chronic conditions [1]. Furthermore, increasingly evidence suggests that survivors of breast cancer are at higher risk of developing new chronic conditions compared to cancer-free controls [2, 3] although this pattern has not been replicated in all studies [4]. For example, in a study of over 900 breast cancer patients in the USA, 66% of white and 86% of black patients had at least one comorbidity and 28% and 35% respectively had 3 or more [5]. Similarly, a report from McMillan Cancer Charities in the UK showed that four out of five women who were 7 years or more post completion of treatment for breast cancer had comorbidities that required inpatient management [6]. The report, if anything, likely underestimated the rates of comorbidities as it focused only on those severe enough to require hospitalisation.

The presence of comorbidities has been shown to influence treatment choice, uptake and toxicity, cancer and non-cancer survival, quality of life and cost of care, making it a priority for research and practice in cancer [7–10]. Indeed, the management of comorbid conditions is explicitly recognised as an important part of effective survivorship care [11] but the delivery of effective care of comorbid chronic conditions in the context of cancer poses several potential challenges. For example, the management of comorbid conditions requires greater care coordination within the cancer setting and the broader health care setting with input from other health care professionals, especially primary care providers who have the necessary skills to manage chronic conditions [12]. The care of comorbidities may not be prioritised by the patient or their health care providers [13]. There are limited tools and care pathways that explicitly integrate management into the breast care pathway [14]. Lastly, there is a relative scarcity of evidence regarding the management of comorbidities. A recent umbrella review of reviews related to interventions for breast cancer survivors identified that out of 323 reviews only seven (2%) addressed the management of chronic conditions [15]. A qualitative systematic review of cancer and comorbid illness demonstrated relative scarcity of evidence on patient experiences of living with comorbid illness [16].

To better understand the pattern of comorbid conditions experienced by breast cancer survivors, their impact and the quality of their care, we conducted a survey of Australian cancer survivors using validated measures of comorbidity and chronic condition management. Specifically, the survey aimed to address the following objectives: (1) examine the self-reported prevalence of comorbidity in women with history of breast cancer; (2) evaluate the impact of comorbidities on self-perceived health status; and (3) assess the quality of care delivered for management of comorbid chronic conditions as compared to care delivered for cancer.

Methods

A study-specific survey was developed and pilot tested with a small group of researchers and consumers. In addition to demographic questions, the survey incorporated questions about the presence of chronic conditions, functional status and perceived quality of care for cancer and non-cancer conditions (Supplementary material 1) . Comorbidity burden was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)—a validated measure that lists 23 chronic conditions plus an option of including “other” and directly indicating that condition [17]. The entries for “other” conditions were reviewed and if appropriate added to the main categories and the CCI score was calculated. Functional status was assessed using the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES)—a validated 13-item function-based scoring system that considers age, self-rated health, limitation in physical function and functional disabilities [18]. The perceived quality of care for cancer and non-cancer conditions was assessed using the Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions Survey (PACIC) [19]. PACIC includes 20 questions across five subscales: patient activation; delivery system design/decision support; goal setting; problem-solving/contextual counselling; and follow-up/coordination. Study participants were asked to complete PACIC questions about the management of the conditions other than cancer and again about management of the cancer itself.

Members of Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA) were invited via email to complete the survey either online or they could request a hard copy of the survey to be posted and returned via mail. BCNA is a national advocacy organisation of approximately 100,000 members, many of whom have previously indicated willingness to take part in surveys relevant to breast cancer. Completion of the questionnaire implied consent. Ethical approval for the study was provided by the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network Hospital Research Ethics Committee (application 367.16).

Differences in PACIC score between chronic disease care and cancer care were assessed using paired-sample t-test and mixed effect model. The distribution of PACIC overall score and five subscale scores were assessed using histogram and normality test. None of these measures is normally distributed, and none of conventional transformation could achieve normal distribution. Therefore, the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test was also performed. The between group differences in PACIC were also assessed by using multivariable mixed effect model, in which patient’s demographic variables and VES score were included for adjustment. All analyses were performed using Stata MP 14.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA). All tests were two-sided, with a p value < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

The survey was sent to 2198 members of BCNA directly from BCNA. The researchers had no direct contact with potential participants and only one invitation to complete the survey was sent. A total of 177 responses were received (response rate 8.1%) but not all respondents completed all questions. All were women with mean age of 60.1 years (range 32–88). The majority had Australian cultural background (85.9%), were married (67.7%), had private health insurance (80.0%), and approximately a third were employed (37.6%). The majority described their health as good, very good or excellent (73.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (n = 177)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Agree to proceed the interview | n = 177 |

| Age in years, n = 149 | 60.1 (9.3) |

| Marital status, n = 170 | |

| Single | 21 (13.4) |

| Married | 115 (67.7) |

| De facto | 13 (7.6) |

| Divorced | 13 (7.6) |

| Widowed | 7 (4.1) |

| Prefer not to tell | 1 (0.6) |

| Employment status, n = 170 | |

| Unemployed | 3 (1.8) |

| Employed | 64 (37.6) |

| Retired | 80 (47.1) |

| Home duties | 11 (6.5) |

| Other | 11 (6.5) |

| Prefer not to tell | 1 (0.6) |

| Income, n = 170 | |

| $0–$6000 | 3 (1.8) |

| $6000–$35,000 | 40 (23.5) |

| $35,000–$80,000 | 47 (27.7) |

| $80,000–$180,000 | 34 (20.0) |

| Over$180,000 | 13 (7.6) |

| Prefer not to tell | 33 (19.4) |

| Living arrangement, n = 169 | |

| Other living arrangement | 134 (79.3) |

| Living alone | 33 (19.5) |

| Prefer not to tell | 2 (1.2) |

| Had private health insurance, n = 170 | |

| No | 34 (20.0) |

| Yes | 136 (80.0) |

| Culture background, n = 170 | |

| Other | 24 (14.1) |

| Australia | 146 (85.9) |

| General health, n = 162 | |

| Poor | 8 (4.9) |

| Fair | 35 (21.6) |

| Good | 73 (45.1) |

| Very good | 44 (27.2) |

| Excellent | 2 (1.2) |

| VES score, mean (SD), n = 141 | 2.7 (2.2) |

Chronic conditions other than cancer were reported by 157 (88.7%) respondents. The median number of chronic conditions reported was three; with 40 women (22.7%) reporting four or more. The majority of respondents (63.8%) reported the presence of a condition that was not explicitly listed in the CCI. The most common comorbidities included chronic pain (27.1%), persistent fatigue (19.8%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (16%), osteoporosis (15.8%), peripheral neuropathy (15.2%) and arthritis (14.1%). Of these, only airways disease was explicitly included in the CCI scores—the remainder were classified as “other” (Table 2). Both the number of chronic conditions and the CCI score correlated with inferior perceived health (rho = − 0.29, p < 0.001; and rho = − 0.24, p = 0.002, respectively) and the VES score (rho = 0.37, p < 0.001; and rho = 0.23, p = 0.007, respectively).

Table 2.

Comorbid chronic conditions

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| (n = 177) | |

| Presence of any chronic condition (CC) | 157 (88.7) |

| Conditions listed in CCI | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 29 (16.4) |

| Arm or leg weakness | 24 (13.6) |

| Mental disorder (including depression and bipolar) | 23 (13.0) |

| Diabetes with chronic complication | 16 (9.0) |

| Renal disease | 4 (2.3) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1 (0.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (1.7) |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (2.8) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2 (1.1) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (0.6) |

| Liver disease (mild) | 7 (4.0) |

| Liver disease (moderate/severe) | 2 (1.1) |

| Leukaemia | 1 (0.6) |

| Malignant tumour—not metastatic | 169 (95.5) |

| Malignant tumour—metastatic | 8 (4.5) |

| Chronic conditions (other than those listed in CCI) | |

| Chronic pain | 48 (27.1) |

| Persistent fatigue | 35 (22.0) |

| Osteoporosis | 28 (15.8) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 27 (15.2) |

| Arthritis | 25 (14.1) |

| Lymphedema | 19 (10.7) |

| Obesity | 14 (7.9) |

| Total CCI score (age adjusted, mean (SD)) | 4.4 (1.9) |

| CC number (as used in CCI scoring) | |

| 1 | 93 (52.5) |

| 2 | 52 (29.4) |

| 3 | 26 (14.7) |

| 4 | 5 (2.8) |

| 6 | 1 (0.6) |

| Total number of any CC | |

| 1 | 34 (19.3) |

| 2 | 50 (28.4) |

| 3 | 52 (29.6) |

| 4 or more | 40 (22.7) |

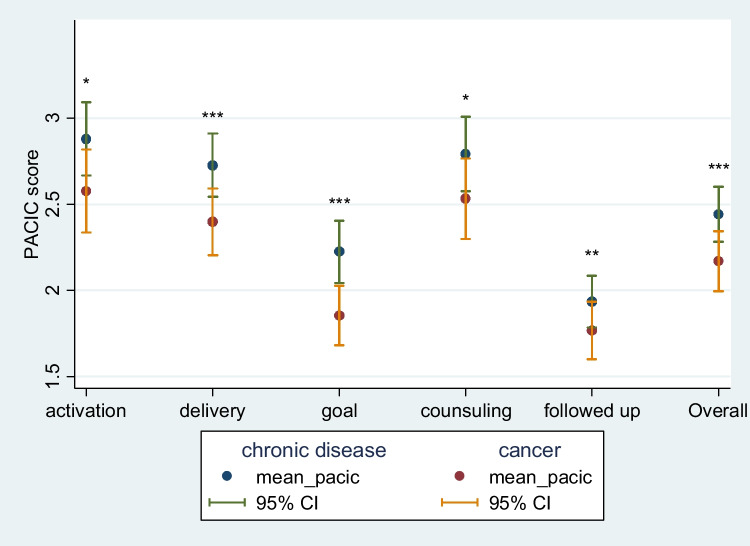

When asked about management of chronic conditions, 49 (34%) respondents said they were never asked for input into their management plan, 29 (20%) were never given choices about treatment, 40 (28%) were never asked to talk about side effects of medicines, 49 (35%) were never advised about self-management options, 65 (45%) were never asked about goals of care, and 63 (44%) were never asked about health habits (Table 3). Corresponding rates for cancer care were 51 (40%) for never asked for input into management, 44 (34%) for never given choices about treatment, 44 (34%) for never being asked about side effects, 89 (69%) for never being advised about self-management options, 72 (56%) for never being asked about goals of care and 73 (57%) for never being asked about health habits (Table 4). Overall, 48 (35%) were never asked how their chronic condition affected their life and 84 (61%) were never encouraged to attend community programs to help with the management of chronic conditions. Corresponding figures for cancer were 58 (46%) and 89 (70%), respectively. Overall, mean PACIC overall score and five subscale scores, whilst generally low, were higher for management of chronic conditions compared to cancer care management, and these results were confirmed by the rank test results (Fig. 1, Table 5, all p < 0.05 in t-test). The significance remained when adjusted for demographic variables (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Response to the request to complete the statement: “Over the past 6 months, when I received care for my chronic conditions aside from cancer, I was…”

| None of the time (n; %) | A little of the time (n; %) | Some of the time (n; %) | Most of the time (n; %) | Always (n; %) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asked for my ideas when we made a treatment plan | 49; 34.0% | 17; 11.8% | 31; 21.5% | 22; 15.3% | 25; 17.4% | 144 |

| Given choices about treatment to think about | 29; 20.3% | 23; 16.1% | 33; 23.1% | 28; 19.6% | 30; 21.0% | 143 |

| Asked to talk about any problems with my medicines or their effects | 40; 28.0% | 18; 12.6% | 29; 20.3% | 28; 19.6% | 28; 19.6%; | 143 |

| Given a written list of things I should do to improve my health | 75; 53.6% | 20; 14.23% | 16; 11.4% | 14; 10.0% | 15; 10.7% | 140 |

| Satisfied that my care was well organized | 12; 8.5% | 23; 16.2% | 25; 17.6% | 50; 35.2% | 32; 22.5% | 142 |

| Shown how what I did to take care of myself influenced my condition | 49; 35.0% | 23; 16.4% | 24; 17.1% | 26; 18.6% | 18; 12.9% | 139 |

| Asked about my goals in caring for my condition | 65; 45.8% | 25; 17.6% | 22; 15.5% | 19; 13.4% | 11; 7.78% | 138 |

| Helped to set specific goals to improve my eating and exercise | 65; 46.8% | 23; 16.6% | 27; 19.4% | 16; 11.5% | 8; 5.% | 139 |

| Given a copy of my treatment plan | 64; 46.4% | 14; 10.1% | 14; 10.1% | 24; 17.4% | 22; 15.94% | 138 |

| Encouraged to go to a specific group or class to help me cope with my chronic condition | 80; 56.3% | 15; 10.6% | 24; 16.9% | 13; 9.2% | 10; 7.0% | 142 |

| Asked questions, either directly or on a survey, about my health habits | 62; 44.0% | 24; 17.0% | 24; 17.0% | 18; 12.8% | 13; 9.2% | 141 |

| Sure that my doctor or nurse thought about my values, beliefs, and traditions when they recommended treatments to me | 36; 25.9% | 19; 13.7% | 13; 9.4% | 44; 31.7% | 27; 19.4% | 139 |

| Helped to make a treatment plan that I could carry out in my daily life | 39; 28.3% | 19; 13.8% | 23; 16.7% | 32; 23.2% | 25; 18.1% | 138 |

| Helped to plan ahead so I could take care of my condition even in hard times | 51; 37.0% | 23; 16.7% | 15; 10.9% | 31; 22.5% | 18; 13.0% | 138 |

| Asked how my chronic condition affects my life | 48; 34.8% | 24; 17.4% | 21; 15.2% | 23; 16.7% | 22; 15.9% | 138 |

| Contacted after a visit to see how things were going | 101; 73.2% | 21; 15.2% | 5; 3.6% | 9; 6.5% | 2; 1.4% | 138 |

| Encouraged to attend programs in the community that could help me | 84; 61.3% | 25; 18.3% | 15; 101.0% | 9; 6.6% | 4; 2.9% | 137 |

| Referred to a dietitian, health educator or counsellor | 80; 58.8% | 19; 14.0% | 20; 14.7% | 8; 5.9% | 9; 6.6% | 136 |

| Told how my visits with other types of doctors, like an eye doctor or other specialist, helped my treatment | 69; 50.0% | 21; 15.2% | 22; 15.9% | 13; 9.4% | 13; 9.4% | 138 |

| Asked how my visits with other doctors were going | 53; 38.4% | 27; 19.6% | 19; 13.8% | 21; 15.2% | 18; 13.0% | 138 |

Table 4.

Response to the request to complete the statement: “Over the past 6 months, when I received care for my cancer, I was…”

| None of the time (n; %) | A little of the time (n; %) | Some of the time (n; %) | Most of the time (n; %) | Always (n; %) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asked for my ideas when we made a treatment plan | 51; 39.5% | 25; 19.4% | 17; 13.2% | 18; 14.0% | 18; 14.0% | 129 |

| Given choices about treatment to think about | 44; 34.1% | 27; 20.9% | 18; 14.0% | 23; 17.8% | 17; 13.1% | 129 |

| Asked to talk about any problems with my medicines or their effects | 44; 34.1% | 21; 16.3% | 16; 12.4% | 20; 15.5% | 28; 21.7% | 129 |

| Given a written list of things I should do to improve my health | 89; 69.0% | 12; 9.3% | 14; 10.9% | 8; 6.2% | 6; 4.7% | 129 |

| Satisfied that my care was well organized | 26; 20.0% | 20; 15.4% | 19; 14.6% | 36; 27.7% | 29; 22.3% | 130 |

| Shown how what I did to take care of myself influenced my condition | 58; 45.0% | 20; 15.5% | 29; 14.7% | 29; 14.7% | 23; 10.1% | 129 |

| Asked about my goals in caring for my condition | 72; 55.8% | 13; 10.1% | 20; 15.5% | 16; 12.4% | 8; 6.2% | 129 |

| Helped to set specific goals to improve my eating and exercise | 78; 60.9% | 22; 17.2% | 13; 10.2% | 7; 5.5% | 8; 6.3% | 128 |

| Given a copy of my treatment plan | 82; 64.1% | 16; 12.5% | 11; 8.6% | 9; 7.0% | 10; 7.8% | 128 |

| Encouraged to go to a specific group or class to help me cope with my chronic condition | 87; 67.4% | 16; 12.4% | 14; 10.9% | 7; 5.4% | 5; 3.9% | 129 |

| Asked questions, either directly or on a survey, about my health habits | 73; 56.6% | 19; 14.7% | 16; 12.4% | 12; 9.3% | 9; 7.0% | 129 |

| Sure that my doctor or nurse thought about my values, beliefs, and traditions when they recommended treatments to me | 39; 30.7% | 20; 15.8% | 14; 11.0% | 25; 19.7% | 29; 22.8% | 127 |

| Helped to make a treatment plan that I could carry out in my daily life | 49; 38.6% | 18; 14.2% | 15; 11.8% | 25; 19.7% | 20; 15.8% | 127 |

| Helped to plan ahead so I could take care of my condition even in hard times | 56; 44.4% | 19; 15.1% | 19; 15.1% | 21; 16.7% | 11; 8.7% | 126 |

| Asked how my chronic condition affects my life | 58; 46.0% | 20; 15.9% | 17; 13.5% | 12; 9.5% | 19; 15.1% | 126 |

| Contacted after a visit to see how things were going | 9; 76.2% | 8; 6.4% | 12; 9.5% | 6; 4.8% | 4; 63.2% | 126 |

| Encouraged to attend programs in the community that could help me | 89; 70.1% | 15; 11.8% | 12; 9.5% | 6; 4.7% | 5; 3.9% | 127 |

| Referred to a dietitian, health educator or counsellor | 92; 73.0% | 13; 10.3% | 8; 6.4% | 9; 7.1% | 4; 3.2% | 126 |

| Told how my visits with other types of doctors, like an eye doctor or other specialist, helped my treatment | 81; 63.3% | 15; 11.7% | 12; 9.4% | 12; 9.4% | 8; 6.3% | 128 |

| Asked how my visits with other doctors were going | 60; 46.89% | 24; 18.8% | 15; 11.7% | 13; 10.1% | 16; 12.5% | 128 |

Fig. 1.

Overall PACIC scores and scores of five subscales for chronic disease and cancer care. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, derived from paired sample t-test

Table 5.

PACIC overall score and subscales

| Chronic disease | Cancer | Difference | p1 | p2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean [95% CI] | |||

| Activation, n = 128 | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.4) | 0.2 [0.02, 0.5] | 0.03 | 0.0497 |

| Delivery, n = 129 | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.1) | 0.3 [0.1, 0.5] | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Goal, n = 128 | 2.2 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.0) | 0.4 [0.2, 0.5] | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Counselling, n = 127 | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | 0.2 [0.04, 0.4] | 0.02 | 0.003 |

| Follow-up, n = 128 | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.0) | 0.2 [0.03, 0.3] | 0.02 | 0.008 |

| Overall, n = 130 | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.0) | 0.3 [0.1, 0.4] | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

1p values are derived from paired sample t-test; 2p values are derived from Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test

Discussion

This cross-sectional survey of Australian breast cancer survivors highlights that comorbid chronic conditions were common in this group; their presence correlated with inferior perceived health, and their care poorly aligned with best practice in chronic condition management. Nearly 90% of respondents had some form of chronic condition in addition to cancer and nearly a quarter had four or more. These rates were higher than some of the other studies of breast cancer survivors likely reflecting the selection bias of survey respondents. In addition, our study considered not only the conditions listed explicitly by the CCI but also those that the CCI would normally categorise as “other” but are common among breast cancer survivors such as lymphoedema, neuropathy, osteoporosis or arthritis [20–23]. This highlights the relative limitations of the CCI in this population and the need for developing comorbidity assessment tools that are specific for the types of comorbidities that are more likely to occur in women with breast cancer.

The assessment of the quality of care received for the management of chronic conditions demonstrated poor alignment with best practice in chronic condition management in this otherwise relatively young, healthy, insured and at least e-health literate population, given the mode of distribution of the survey. One could argue that a potential explanation might be the lack of awareness or prioritisation of management of chronic conditions by the participants themselves. However, this possibility seems unlikely given that the observed quality of cancer care in this cohort was even worse. This observation suggests the presence of more systemic deficiencies in the care delivery for cancer survivors or perhaps in chronic care delivery in general. PACIC, the tool used in the present study, is designed to assess the delivery of chronic care management from the patient’s perspective and has been extensively used in other chronic conditions [24]; but we are not aware of similar data in cancer. Further research into the quality of cancer care, and specifically the care of comorbid chronic conditions in the context of cancer care, is warranted.

The study findings need to be interpreted in the context of the survey limitations. The response rate was low, consistent with this type of survey, but likely to lead to a significant selection bias. It is notable however that respondents were relatively young, considered themselves healthy and with better health literacy given the mode of recruitment. It is therefore possible that the findings in this study underestimate the problem of comorbidities. Comorbid chronic conditions are more likely to occur in patients who are older, frailer and in those with lower socioeconomic status where both cancer outcomes and outcomes of comorbidities are poor [25]. Future studies should focus on experiences of living with chronic disease specifically in these populations. If these findings are replicated in other studies with larger response rates, more consideration could be given to models of care based on the chronic care model [26]. Further consideration could be made of training of primary care providers and cancer care providers in chronic condition management and the role of self-management to improve outcomes for patients living with cancer and comorbid chronic conditions.

In conclusion, comorbid chronic conditions are common among breast cancer survivors. In this population of survivors with good health status and high rates of private insurance, the management of chronic conditions and the management of breast cancer itself demonstrated limited alignment with established chronic disease management principles. This indicates important gaps in care delivery as well as missed opportunities for early intervention that warrant further attention.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Bogda Koczwara and Rosie Meng. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Bogda Koczwara and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions Flinders Medical Centre Foundation Research Grant.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee.

Consent to participate

Consent was assumed by response to the survey.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bogda Koczwara, Email: bogda.koczwara@flinders.edu.au.

Rosie Meng, Email: rosie.meng@flinders.edu.au.

Malcolm Battersby, Email: malcolm.battersby@flinders.edu.au.

Arduino A. Mangoni, Email: arduino.mangoni@flinders.edu.au

Danielle Spence, Email: danielle.spence@cancervic.org.au.

Sharon Lawn, Email: Sharon.lawn@flinders.edu.au.

References

- 1.Ogle KS, Swanson GM, Woods N, Azzouz F. Cancer and comorbidity. Cancer. 2000;88:653–663. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000201)88:33.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng HS, Vitry A, Koczwara B, Roder D, McBride ML. Patterns of comorbidities in women with breast cancer: a Canadian population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30:931–941. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng HS, Koczwara B, Roder DM, Niyonsenga T, Vitry AI. Comorbidities in Australian women with hormone-dependent breast cancer: a population-based analysis. Med J Aust. 2018;208(1):24–28. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Möhl A, Orban E, Jung AY, Behrens S, Obi N, Chang-Claude J, Becher H. Comorbidity burden in long-term breast cancer survivors compared with a cohort of population-based controls from the MARIE study. Cancer. 2021;127(7):1154–1160. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tammemagi CM, Nerenz D, Neslund-Dudas C, et al. Comorbidity and survival disparities among black and white patients with breast cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:17765–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Routes from diagnosis . the most detailed picture of cancer survivorship yet. London: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee L, Cheung WY, Atkinson E, Krzyzanowska MK. Impact of comorbidity on chemotherapy use and outcomes in solid tumors: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):106–117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Søgaard M, Thomsen RW, Bossen KS, Sørensen HT, Nørgaard M. The impact of comorbidity on cancer survival: a review. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5(Suppl 1):3–29. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S47150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crouch A, Champion VL, Von Ah D. Comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, physical functioning, and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):359–366. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06427-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng HS, Koczwara B, Roder D, Chan RJ, Vitry A. Patterns of health service utilisation among the Australian population with cancer compared with the general population. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44(3):470–479. doi: 10.1071/AH18184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120–1130. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):337–350. doi: 10.3322/caac.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark RA, Marin TS, Berry NM, Atherton JJ, Foote JW, Koczwara B. Cardiotoxicity and cardiovascular disease risk assessment for patients receiving breast cancer treatment. Cardiooncology. 2017;17(3):6. doi: 10.1186/s40959-017-0025-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster S, Lawn S, Chan R, Koczwara B. The role of comorbidity assessment in guiding treatment decision-making for women with early breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(3):1041–1050. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05218-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemp EB, Geerse OP, Knowles R, Woodman R, Mohammadi L, Nekhlyudov L, Koczwara B (2022) Mapping systematic reviews of breast cancer survivorship interventions: a network analysis. J Clin Oncol JCO2102015. 10.1200/JCO.21.02015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Cavers D, Habets L, Cunningham-Burley S, Watson E, Banks E, Campbell C. Living with and beyond cancer with comorbid illness: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(1):148–159. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-0734-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classification of prognostic comorbidity for longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Disease. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, Roth C, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG, Sloss EM, Wenger NS. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(12):1691–1699. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasgow R, Wagner E, Schaefer J, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Med Care. 2005;43:436–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):500–515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao T, Basal C, Seluzicki C, Li SQ, Seidman AD, Mao JJ. Long-term chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy among breast cancer survivors: prevalence, risk factors, and fall risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159(2):327–33. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3939-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro CL. Osteoporosis: a long-term and late-effect of breast cancer treatments. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(11):3094. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckwée D, Leysen L, Meuwis K, Adriaenssens N. Prevalence of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1673–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3613-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmittdiel J, Mosen DM, Glasgow RE, Hibbard J, Remmers C, Bellows J. Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and improved patient-centered outcomes for chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(1):77–80. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler H, Belot A, Ellis L, Maringe C, Luque-Fernandez MA, Njagi EN, Navani N, Sarfati D, Rachet B. Comorbidity prevalence among cancer patients: a population-based cohort study of four cancers. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6472-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawn S, Battersby M (2016) Chronic condition management models for cancer care and survivorship. In: Koczwara, B. (eds) Cancer and chronic conditions. Springer, Singapore. 10.1007/978-981-10-1844-2_8

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.