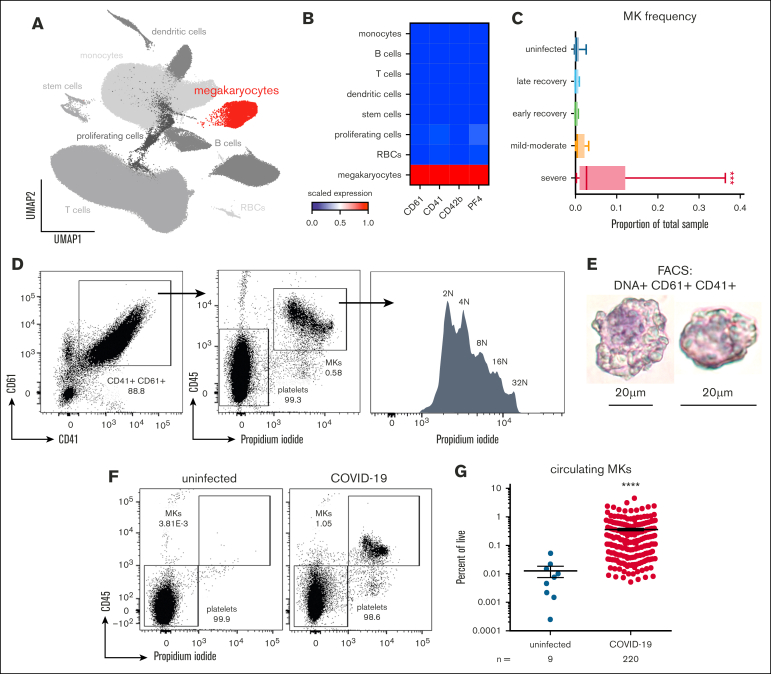

Figure 1.

Circulating MKs are increased in COVID-19. (A) scRNA-seq dimensionality reduction using uniform manifold approximation and projection of 317 562 cells derived from 4 separate studies. MKs (4180 cells) are shown in red. (B) scRNA-seq marker genes used to identify circulating MKs. (C) Frequency of MKs relative to all cells from scRNA-seq samples. Median ± minimum/maximum. Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn post hoc multiple comparisons test. All groups compared with uninfected control. Adjusted P value ∗∗∗P = .001 to .0001. Mild-moderate: n = 15; severe: n = 14; early recovery (<7 days after first negative polymerase chain reaction [PCR] test): n = 8; late recovery (>14 days after first negative PCR test): n = 8; uninfected: n = 19. (D) Flow cytometry from UAB COVID-19 peripheral blood samples (n = 20) showing gating of CD61+ CD41+ DNA–positive MKs. The histogram shows ploidy distribution ranging from 2n to 32n. (E) Cytocentrifugation of FACS-sorted MKs stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (F) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the proportion of MKs relative to platelets in uninfected vs COVID-19 peripheral blood. (G) Quantification of MK frequency, relative to all live events, using flow cytometry on peripheral blood from uninfected (n = 9 donors) vs COVID-19 (n = 218 patients; 220 samples). Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired 2-tailed t test with Welch correction; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance.