Abstract

Implants made of magnesium (Mg) are increasingly employed in patients to achieve osteosynthesis while degrading in situ. Since Mg implants and Mg2+ have been suggested to possess anti-inflammatory properties, the clinically observed soft tissue inflammation around Mg implants is enigmatic. Here, using a rat soft tissue model and a 1–28 d observation period, we determined the temporo-spatial cell distribution and behavior in relation to sequential changes of pure Mg implant surface properties and Mg2+ release. Compared to nondegradable titanium (Ti) implants, Mg degradation exacerbated initial inflammation. Release of Mg degradation products at the tissue-implant interface, culminating at 3 d, actively initiated chemotaxis and upregulated mRNA and protein immunomodulatory markers, particularly inducible nitric oxide synthase and toll-like receptor-4 up to 6 d, yet without a cytotoxic effect. Increased vascularization was demonstrated morphologically, preceded by high expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. The transition to appropriate tissue repair coincided with implant surface enrichment of Ca and P and reduced peri-implant Mg2+ concentration. Mg implants revealed a thinner fibrous encapsulation compared with Ti. The detailed understanding of the relationship between Mg material properties and the spatial and time-resolved cellular processes provides a basis for the interpretation of clinical observations and future tailoring of Mg implants.

Keywords: Magnesium, Biodegradable implants, Inflammation, Foreign-body reaction, Gene expression, Neovascularization

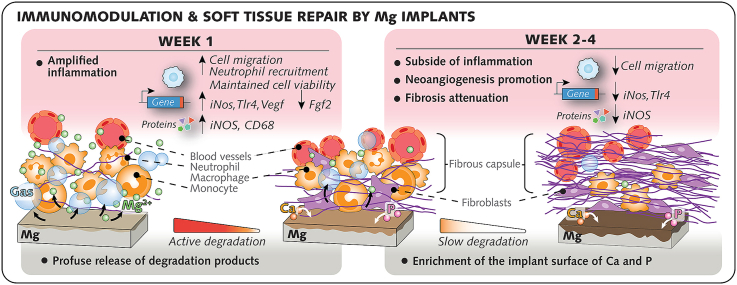

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Temporo-spatial analysis of cell behaviour at Mg implant interface in vivo.

-

•

Initial Mg implant degradation amplifies inflammation but not cytotoxicity.

-

•

Mg implants promote vascularization and attenuate fibrous encapsulation.

-

•

Positive associations were shown between Mg2+ and iNOS protein and gene expression, and Tlr4 gene expression.

-

•

Negative association was demonstrated between Fgf2 gene expression and Mg2+.

1. Introduction

In ever-increasing numbers, patients are being treated with implants made of magnesium (Mg), a metallic biomaterial designed to be eliminated from the body while fulfilling its function in situ [1]. The century-old concept of using Mg implants regained interest during the last two decades, simultaneously with the increased sophistication in controlling their degradation and in improving their mechanical properties [[2], [3], [4]]. Today, Mg-based implants are implemented in routine clinical practice within two primary applications: vascular [5] and orthopedic [6]. The former application refers to Mg biodegradable vascular stents which, in conjunction with angioplasty, enable geometry restoration and vasomotion of diseased vessels beyond complete implant degradation [7]. The latter set of implants (i.e., orthopedic implants) denotes Mg-based osteosynthesis systems that hold fractured bone in place to secure repair before full degradation of the implant [8]. For both applications, long term-studies [[8], [9], [10]] concur that Mg implants meet the need of overcoming the flaws of their conventional permanent analogs: the unwanted re-narrowing of the stented vessel due to a reactive fibrotic proliferation [11], and the inevitable surgical removal of the orthopedic implant after healing of fractured bone [12].

However, a suboptimal outcome or failure is also reported to occur in patients treated with Mg implants. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported a complication rate of ∼13% with Mg-based osteosynthesis implants, although not different from the complication rate with state-of-the-art implants made of titanium (Ti) [13]. While such complications are manifold ranging from events such as pain and infection to osteosynthesis failure [14,15], poor healing around Mg implants has been reportedly linked to an uncontrolled initial response [16]. When implanted in the body, Mg is reactive: it starts degrading immediately upon implantation and resorbs at the fastest rate during the initial postoperative period [17,18]. Thus, the early days after which a Mg-based osteosynthesis implant makes contact with the body involve the greatest release of degradation products [19] into the tissue environment, including bone and the overlying soft tissues alike.

Inflammation of soft tissues in the vicinity of Mg-based osteosynthesis implants is a clinical event documented during the early post-implantation period [16,20]. This inflammation is typically accompanied by subcutaneous radiolucent cavities resulting from the gaseous accumulation generated by the degradation of the nearby Mg implant [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. In most instances where the Mg implant successfully integrates to the recipient bone, the initial inflammation of the peri-implant soft tissues is reported to fully subside together with the gaseous voids a few weeks following implantation [16,[20], [21], [22], [23]]. In contrast, when a Mg implant failure occurs, an exacerbated and persistent soft tissue reaction is described [14]. A soft tissue-damaging inflammation has been linked to the failure of other metallic orthopedic implants, such as cobalt-chromium implants for hip and knee replacement, which release micrometer-sized metallic wear particles and ions [24,25]. By eliciting a persistent inflammation involving a central role of macrophage cytotoxicity, metallic wear byproducts lead to an excessive foreign body response (FBR) in soft tissues [26]. These unanticipated complications raised questions on the safety and biocompatibility of metallic implants in the context of particles and ions deposited in the adjacent tissues.

Mg implants are traditionally assigned anti-inflammatory properties [27,28]; the underlying assumption being the widely reported potency of Mg2+ administration to attenuate inflammation [[28], [29], [30]]. This however contradicts the reported soft tissue inflammation at the postoperative stage in humans and animals receiving Mg osteosynthesis implants [20,31]. Further, the fast delivery of degradation products from Mg implants to the adjacent tissues might favor fibrosis [32]. The lack of in vivo information on the cellular and molecular response in relation to the degradation of Mg implant has hampered the understanding of the immune response in soft tissues to Mg implants.

Here, we hypothesize that the degradation of Mg implants amplifies the foreign body response (FBR) by promoting the initial inflammation and the subsequent fibrotic encapsulation. To test this assumption, we sequentially monitored the degradation of Mg implants and the linked cellular response from days 1–28 upon implantation in soft tissues in comparison to nondegradable Ti implants. We employed a rat subcutaneous model [[33], [34], [35]] previously used to scrutinize the cellular response at three topographically distinct compartments of the soft tissue interface with implants (Fig. 1A): the cells adherent to the implant surface, the inflammatory fluid around the implant (exudate), and the soft tissue per se. The results reveal that the initial in situ local release of degradation products from Mg implants, which culminates at 3 d in vivo and in vitro, triggers a robust proinflammatory response in soft tissue during the first postoperative week, yet without a cytotoxic effect in comparison to the response to Ti implants. Thereafter, the inflammation around Mg implants markedly subsides when the release of degradation products declines in the peri-implant exudate simultaneously with the development of a protective layer rich in calcium and phosphorus at the surface of Mg implants. This allows the assembly of a more vascularized and thinner fibrous capsule around Mg implants in comparison to Ti implants. An amplified inflammation of the soft tissue initially in response to Mg implants is demonstrated, but is tuned by the degradation dynamics to improve vascularization and to attenuate fibrosis, with implications expanding to other tissue types.

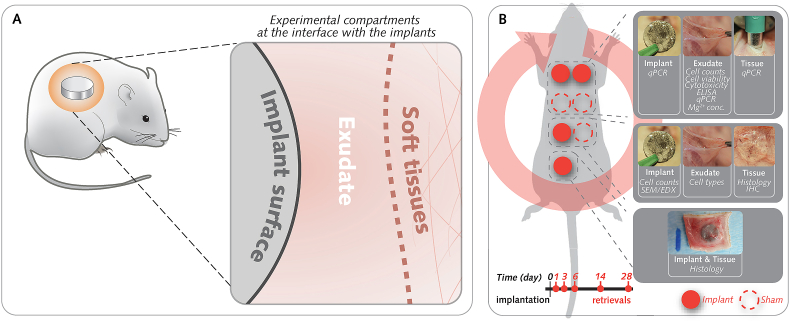

Fig. 1.

The rat subcutaneous model allows the compartmentalization of the interface with the implants.

(A), The cellular response was characterized at three topographically distinct compartments of the soft tissue-implant interface: the cells adherent to the implant surface, the inflammatory fluid around the implant (exudate), and the soft tissue per se. (B), Four implants were inserted in each rat in addition to three sham wounds without implants. At 1-, 3-, 6-, 14-, and 28-days following implantation, the separate retrieval of implants, exudates, and tissues allowed the monitoring of Mg2+ concentration at the interface along with cellular (cell counts, cell viability, and cytotoxicity) and molecular analyses (gene expression with qPCR analysis; protein analyses with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and immunohistochemistry [IHC]). In addition, implants and tissues that were collected en bloc were allocated for morphometric analyses of tissues (histology and histomorphometry) and the Mg-degradation layer (SEM, secondary electron microscopy; EDX: energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy). Random allocation of pockets to the different retrieval groups was achieved through a clockwise rotation scheme, as shown by the red circular arrow.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Implants

High-purity Mg (99.995%) discs (thickness = 1.4 mm, diameter = 9 mm) were fabricated as described previously [36]. Discs of identical dimensions were machined from commercially pure titanium grade IV. Chemical compositions of the as-manufactured discs were determined using spark emission spectroscopy (Table S1). Manufactured Mg implants were polished using 2500 grit SiC grinding paper, then cleaned by ultrasonic bathing in n-hexane, acetone, and ethanol (100%) successively, followed by air-drying in a vacuum. Individually packed Mg implants were then sterilized by gamma irradiation at a dose of 30.2 kGy (BBF GmbH, Stuttgart). Manufactured Ti implants were cleaned by ultrasonic bathing in extran and ethanol (70%), successively, followed by air-drying. Individually packed Ti implants were then steam-sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min.

2.2. Preimplantation characterization

Surface characterization Mg and Ti implants (n = 3 each), that were cleaned and sterilized, were used for scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SU-8000, Hitachi) performed in the backscattered electron (BS-SEM) and secondary electron (SE−SEM) modes at 15 kV accelerating voltage. Chemical composition of the Mg implants was evaluated by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX; UltraDry EDS Detector, NSS software v. 3.2, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 15 kV and 15 mm working distances. Surface roughness (Sa) was determined using confocal laser-scanning microscopy (VK-1000, Keyence) equipped with a 20x objective. Nine 100 × 100 μm2 regions on each of Mg and Ti implant surface (n = 3 each), were analyzed.

Microstructure analyses Cross-sections were prepared using metallographic cutting equipment (MICRACUT 151, Metkon). For Mg implants, glycerol in ethanol, 1:3 (v/v), was used as the coolant. Ti and Mg implants were polished, followed by ion milling (IM 4000, Hitachi). SEM (SU-8000, Hitachi) and elemental analysis using EDX (UltraDry EDS Detector, NSS software v. 3.2, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were performed at accelerating voltages of 5 kV (imaging) and 15 kV (EDX), a 15 mm working distance, and a 20 μA beam current. In addition, electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) was performed by SEM (SU-70, Hitachi) equipped with an e−FlashHD detector (Bruker Microanalysis System) at 20 kV and at step sizes of 0.2 μm and 1.5 μm for Ti and Mg implants, respectively, followed by data processing with HKL Channel 5 software v. 5.0.

Natural oxidation study Mg implants from the same batch used in vivo were randomly selected and characterized. On each day scheduled for surgical implantation in animals, the entire surface of n = 3 Mg implants was examined under an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope coupled with an OPTA-Tech HDMI camera, and images of the entire surface were taken at 2x magnification. SEM observations of the surface of the discs were also performed at 30x, 500x and 5000x magnification and at a 5 kV acceleration voltage (Hitachi, SU-8000). To identify oxygen-rich regions, point measurements using EDX were performed at selected areas at 15 kV.

2.3. In vitro immersion test of Mg implants

Cleaned and sterilized Mg implants (n = 54) were individually immersed in 2 mL of alpha-minimum essential medium (α-MEM; Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Invitrogen) under sterile cell culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% controlled humidity) in an incubator (Heraeus BBD 6620, Fisher Scientific). Immersion times were 1, 3, 6, 14, 21, and 28 d (n = 9/time point). Control medium samples (n = 3/time-point) did not receive Mg implants. All media were changed every 2–3 days to maintain semistatic immersion conditions [37]. The pH and osmolality were recorded prior to implant immersion and in each collected medium postimmersion. The pH of the initial culture medium was measured using a pH meter (Sentron® SI600, Sentrom Europe BV) with a MiniFET probe. Similarly, the initial osmolality of the immersion medium was recorded by a cryoscopic osmometer (OSMOMAT® auto, Gonotec GmbH). The pH and osmolality of the supernatant were measured at each change in the implant-containing medium or control medium.

In addition, to calculate the degradation rate and depth, all implants were retrieved and weighed before and after removal of degradation products with chromic acid (180 g/L in distilled water, VWR International). The weight of each treated disc was measured to calculate the degradation rate (DR; mm/year) based upon the following formula (ASTM G1-03 2017):

| (1) |

where Δg is the difference in implant weight prior to immersion and after chromic acid treatment (g), A is the implant surface area (cm2), t is the immersion time (h) and p is the density of the disc (g/cm3).

The degradation depth (h; μm/day) was estimated by the following linear regression line equation [38]:

| (2) |

where t is the total time of incubation (days), h0 is the y-intercept describing the initial reactions during the immersion test, and h∞ is the slope value representing the mean degradation rate.

2.4. Animal model and surgical procedure

Animal experiments were approved by the Local Ethical Committee for Laboratory Animals at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden (Dnr-02437/2018), and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. Sprague-Dawley male rats (N = 100; 250–350 g; Taconic Biosciences), housed together (maximum 4 rats/cage) on a 12-12-h dark-light cycle with free access to water and standard rodent diet, were used. In brief, animals were anesthetized by administering 4% isoflurane by inhalation. The back of each rat was shaved and cleaned, and seven separate incisions were made to create subcutaneous pockets by blunt dissection. Experimental sites received implants (n = 4; Mg or Ti in each rat) or were left without implants (n = 3, Sham Ti or Sham Mg in each rat) before closure with nonresorbable sutures (Figs. S1A and B). The back was cleaned and rats were recovered from anesthesia before returning to animal house. For purpose of analgesia, Temgesic (Reckitt Benckiser; 0.03 mg/kg) was subcutaneously administrated at immediate- and at 8 h-postoperative. Animals were sacrificed with an overdose of pentobarbital after 1, 3, 6, 14, or 28 d (n = 20/time point). Four types of samples were retrieved from each rat according to a randomization scheme (Fig. 1B):

-

1

Implants (n = 8-9/group/time point): collected following pocket re-entry for analyses of adherent cells (counting or gene expression) or for morphological and chemical analyses of implant surface.

-

2

Peri-implant exudate (n = 8-9/group/time point): obtained by lavage of the pockets with Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline. Each retrieved volume was divided for analyses of cells (counting, viability, cytotoxicity, type, or gene expression) or for measurement of Mg2+ concentration.

-

3

Peri-implant tissue (n = 8-9/group/time point): retrieved for histology or gene expression analysis.

-

4

Implant and peri-implant tissue (n = 8/group/time point): dissected en bloc for histology and for morphological analyses.

2.5. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

qPCR was performed on cells in the different compartments: 1- Exudate (n = 8-9/group/time point): cells in the remaining volume after the deduction of samples used to determine cell counts were pelleted by centrifugation (400×g, 5 min) and lysed in RNA preservation medium (RNA Shield, Zymo Research); 2- Implant surface (n = 8-9/group/time point): retrieved implants were placed in RNA Shield solution for the lysis of adherent cells. Cell lysates were then frozen (−80 °C); and 3- Soft tissue (n = 8/group/time point): biopsies using 6 mm-diameter-punches of experimental sites were homogenized in RNA Shield to an aqueous phase using a TissueLyser instrument (Qiagen GmbH), and frozen (−80 °C).

RNA was extracted from the cells in all samples using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen GmbH) following manufacturer's instructions. A pilot study representative of the present experiments allowed to verify RNA quality (Pico 6000 RNA Kit in Bioanalyzer 2100 electrophoresis system, Agilent Technologies) and RNA concentration (Nanophotometer P-36, Implen GmbH) in samples from all three compartments. Reverse transcription into cDNA was carried out using TATAA GrandMaster cDNA Synthesis Kit (TATAA Biocenter AB), following manufacturer's instructions. Predesigned and validated primers were purchased (Integrated DNA Technologies). The panel of genes of interest in all three compartments is provided in Table S2. Reference gene screening was performed using a rat reference gene panel (TATAA Biocenter AB) and determined with GeNorm and Normfinder (GenEx software, Multid). The most stable reference gene expression was achieved for GAPDH, which was used for normalization. Normalized relative quantities were calculated using the delta-delta-Cq method.

2.6. Histology, immunohistochemistry, and image analysis

Peri-implant tissues with implants dissected en bloc (n = 8–9/group/time point) were fixed in formalin, and dehydrated prior to embedding in plastic (LR White; London Resin Company Ltd.) [39], then cut transaxially (EXAKT Apparatebau GmbH & Co). Ground sections, 15-20 μm-thick, were stained with 1% toluidine blue. In addition, samples consisting of soft tissues from wounds without implants (n = 8–9/group/time point) were fixed in formalin, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at a thickness of 3–5 μm (Reichert-Jung), deparaffinized in xylene, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Histology, and histomorphometry were blindly performed under an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600, Nikon). Full-slide scans from all sections were acquired with a Plan Apo 20x/0.75 objective using imaging software (NIS-Elements, Nikon) and transferred to image analysis software using identical settings and thresholds applied to all slides.

Images of toluidine blue-stained sections (implant and peri-implant tissues) were transferred to Fiji software [40] to perform the following measurements in a standardized fashion using predefined regions of interest (Fig. S1C): 1-The thickness of the peri-implant fibrous capsule was defined in each section at 16 equally distanced locations on the superficial side (implant surface facing panniculus carnosus muscle; 5 locations), on the deep side (implant surface facing the body interior; 5 locations), and on both lateral sides (3 locations for each lateral side); 2-Vessels in the fibrous capsule were identified, and their number, lumen area and distance to the tissue/implant interface were measured on the superficial, deep and lateral sides of the implant as previously described [41]; 3-Mast cells were identified in the fascia underneath the panniculus carnosus on the superficial, deep, and lateral sides of the implants. The mast cell number was measured; 4-Gas voids were counted in the fascia underneath the panniculus carnosus at the superficial, deep, and lateral sides of Mg implants. The area of each void was measured.

To count total cells in tissues, full-slide images of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (tissues without implants or sham tissues) were imported into QuPath software (v0.3.2) [42]. Semi-automated cell counting, based upon the detection of hematoxylin-stained nuclei, was performed in regions of interest (ROIs) defined as the total tissue area underneath the panniculus carnosus and as the peri-implant fibrous capsule (Fig. S1D). In addition, sections from the dorsum subcutis in unwounded animals were used as baseline controls to measure, in the subcutaneous fascia, the baseline total cellularity (in the respective ROIs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides; n = 6).

For immunohistochemistry, tissue sections (n = 5–6, at 3 d and 28 d in Mg and Ti-implanted sites) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, washed in PBS, incubated for 20 min at 90 °C in water bath for antigen retrieval, prior to blocking with 5% goat serum in 4% bovine serum albumin for 30 min. Sections were then incubated with one of the following primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies: anti-rat iNOS (dilution:1:100; PA1036, ThermoFisher), anti-rat CD68 (dilution:1:3000; PA581594, ThermoFisher), anti-rat MRC1 (dilution:1:30; PA5101657, ThermoFisher), or anti-rat ARG1 (dilution:1:300; PA529645, ThermoFisher) for 2 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity detection in all sections was obtained using horseradish peroxidase detection system (Pierce Horseradish PeroxidasE, ThermoFisher) with DAB (Metal Enhanced DAB Substrate Kit, ThermoFisher) as substrate following the manufacturer's instructions. Negative control sections were prepared following the same protocol but without the primary antibody (Fig. S1E).

To quantify iNOS-, CD68-, MRC1-, and ARG1-positive cells, full-slide images of immunohistochemically stained sections were transferred to QuPath software (v0.3.2). In an ROI (Fig. S1F) encompassing the peri-implant tissues within a distance of 200 μm from the interface with the implant, cells were counted using the automated ‘positive cells detections’ plugin (Fig. S1G). The proportion of positive cells was measured in an average of ∼10 000 cells/ROI in each section.

2.7. Surface characterization of the retrieved implants

Mg and Ti implants retrieved without tissues were observed using SE−SEM. Ti implants (n = 2/time point) were fixed in formalin (2 h) and stained with 1% OsO4 (2 h). Mg implants (n = 2/time point) were fixed in 70% methanol (6 min at −20 °C) to prevent inadvertent degradation. The Ti and Mg implants were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (70, 80, 90, 95, and 100% ethanol), allowed to air-dry overnight, and sputter-coated with Au. For chemical analysis of Mg degradation layer using EDX, retrieved Mg implants (n = 3/time point) were fixed in 100% ethanol and allowed to air-dry overnight. On each implant surface, 12 ± 3 randomly selected spots were measured. Complementary chemical analysis of Mg degradation layer (n = 1 implant/time point) with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted on a Thermo Electron™ Microlab 350™ spectrometer using a twin anode source (AlKα and MgKα) operated at 15 kV and an emission current intensity of 20 mA. All peaks were calibrated to the C1s peak binding energy at 285.0 eV.

2.8. Cross-sectional characterization of retrieved Mg implants

Cross-sections of halved specimens of implants with tissues in plastic (n = 5–6/group/time point) were polished up to 4000 grit SiC grinding paper, followed by ion milling (Hitachi, IM-4000). SEM and EDX analyses of selected regions of cross-sections were performed to analyze the degradation layer. BSE-SEM images were segmented using the WEKA plugin in ImageJ [43] for calculation of degradation layer thickness at three random locations per sample.

2.9. Cell number and cell viability assays

The number of cells adherent to the implant (n = 6–7/group/time point) or in the exudate (n = 8–9/group/time point), that were retrieved from animals, was measured using the NucleoCounter® system (ChemoMetec). To count cells adherent to the implants, retrieved implants were immediately immersed in lysis buffer (100 μL, Reagent A100, ChemoMetec) in a 96-well plate and shaken for 2 min at 500 RPM to detach the cells from the implant surface. Implants were then removed from the lysate before adding the stabilization buffer (100 μL, Reagent B, ChemoMetec). The cell sample was then loaded in a NucleoCassette™ containing propidium iodide that stains nuclei for automatic counting of total cells. To count cells in exudate, an exudate fraction was directly loaded in NucleoCassette™ for dead cell quantification. An additional exudate fraction was diluted 1:1:1 with lysis buffer and stabilization buffer and drawn into NucleoCassette™, as described above, to count total cells.

2.10. Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was determined by analyzing the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) content in supernatants that were centrifuged (400×g, 5 min) from dedicated exudate volumes (125 μL; n = 8–9/group/time point) retrieved from animals. Spectrophotometric measurement of lactic acid due to LDH-mediated conversion of pyruvic acid was performed (C-laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg).

2.11. Cell type determination

The cell types in the exudate (100 μL; n = 8–9/group/time point) collected from animals were characterized by applying approximately 50,000 cells to a microscopic slide using cytospin centrifugation. Cells were stained with May-Grünewald-Giemsa, and the polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells among at least 200 cells per slide were counted under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600, Nikon).

2.12. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Fractions of exudate supernatants (100 μL; n = 8–9/group/time point) were allocated to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits to quantify the concentrations of proteins iNOS (Abbexa), VEGF (Abcam), and FGF2 (R&D systems). In brief, undiluted samples were incubated with primary antibodies and washed followed by the addition of secondary antibody for immunoreactivity detection using horseradish peroxidase. Absorbance measurement at 450 nm (Omega BMG LUMIstar) allowed the quantification of protein concentrations in supernatants and standards.

2.13. Characterization of the magnesium content in exudates

Remaining volumes of exudate (n = 8–9/group/time point) sampled from animals were diluted in 1% Hydrochloric acid (dilution factor ∼1:500) to measure the Mg2+ concentration using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; Agilent 5110 ICP-OES). The analysis was validated against interferences using standard addition, with recovery ranging between 90 and 110%. Spectral interferences were evaluated by comparing retrieved data at Mg wavelengths of 279.533 and 280.271 and were negligible.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Comparisons of independent samples (from different materials, different sham wounds, or different time points) were performed using unpaired Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests. Comparisons of paired samples (implanted wounds vs. sham wounds) were performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Spearman correlation and linear regression analyses were used to test statistical associations. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (v.27; IBM Corporation). Differences for which P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Spearman correlation was considered statistically significant if P < 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Material characterization

After manufacturing, cleaning, and sterilization, the surface topography (roughness), microstructure, and chemical composition of disc-shaped pure magnesium (Mg) and titanium (Ti) implants were characterized prior to surgical insertion. Observation of the implant surfaces (Fig. 2A and B; Fig. S2A) using scanning electron microscopy with a secondary electron detector (SE−SEM) showed a unidirectional horizontal lay pattern at the surface of Mg implants and a circular lay pattern at the surface of Ti implants which was attributable to the manufacturing process.

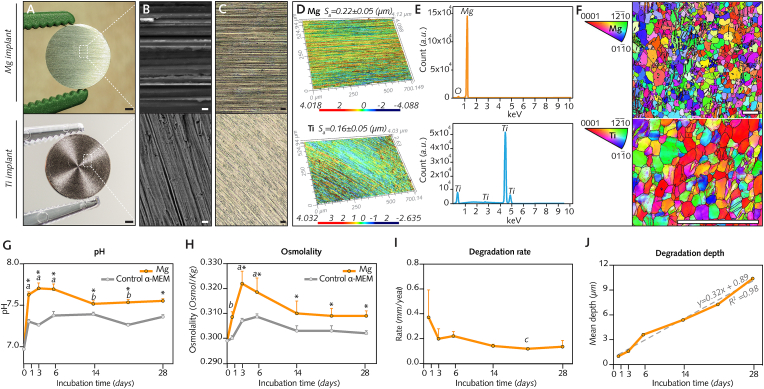

Fig. 2.

Preimplantation characterization and in vitro degradation.

(A), Disc-shaped pure Mg and pure Ti implants after cleaning and sterilization. (B–C, Implant surfaces imaged using secondary electron scanning electron microscopy (SE−SEM) and confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM), respectively. (D), Representative three-dimensional CLSM images of surface roughness and Sa mean measurements (n = 3 implants/group). (E), Chemical composition of implant surfaces analyzed with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). (F), Electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) maps of implant cross-sections showing their microstructure. (G-J), Degradation of Mg implants in vitro was monitored at days 1–28 following immersion in alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (n = 9 implants/time point). Medium was retrieved to measure pH (G) and osmolality (H), while implants were collected and weighed following treatment with chromic acid to measure the degradation rate (I) and degradation depth (J). Identical cell culture media without implants served as controls (n = 3/time point).

Data are means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05 Mg media (α-MEM media with Mg implants) versus Control α-MEM media (without Mg implants). a: P < 0.05 versus Control α-MEM at day 0; b: P < 0.05 versus Mg media at day 3; c: P < 0.05 versus Mg media at day 1. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test. Scale A = 1 mm; B = 5 μm; C = 50 μm; F = 100 μm.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (Fig. 2C and D) revealed that the surface roughness of Mg (0.22 μm ± 0.05 μm) and Ti implants (0.16 μm ± 0.05 μm) was similar. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX; Fig. 2E) demonstrated low levels of oxygen, indicative of a thin superficial oxide film, on Mg implants but not on Ti implants (∼99.8% titanium). This oxidation, consistently observed on the surface of Mg implants in this study (Fig. S2B), is generated by unavoidable exposure to moisture throughout the different steps of Mg implant preparation from manufacturing until storage [44]. In cross-sections of both Mg and Ti implants (Fig. 2F), a hexagonal, closely packed structure with some twin deformation was revealed by scanning electron microscopy with an electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) detector. Areas with a fine grain size featured a uniform and equiaxed grain shape, while in areas with a large grain size, the grain shape was less uniform (Fig. S2C). The mean grain size was 16.87 μm for Mg and 2.45 μm for Ti (Fig. S2D).

3.2. In vitro degradation of Mg implants

Mg implants were further characterized by monitoring their degradation in vitro from 1 to 28 days after immersion in alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum to simulate in vivo milieu [45]. To maintain semistatic immersion conditions [37], the medium was exchanged every 2–3 days. A sharp increase in the pH of the immersion medium (Fig. 2G) was noted at 1 d and 3 d from a baseline pH of 6.9 before the pH stabilized in the range of 7.6–7.9. In parallel, osmolality records (Fig. 2H), which indicate the concentration of dissolved particles in the immersion medium, also showed a clear increase at 1 d and 3 d, suggesting the rapid release of degradation products from Mg implants. This was followed by an overall decrease in osmolality up to 28 d, implying precipitation of these soluble species over time. At all time points, both pH and osmolality remained consistently higher in media with Mg implants than in control media without implants.

Consistent with the changes in pH and osmolality over time, the degradation rate (Fig. 2I), determined by estimating the degradation depth from the weight difference of Mg implants relative to baseline, was the highest at 1 d and then decreased until 28 d. The estimation of the mean degradation depth over time from weight records of Mg implants indicated a linear degradation rate of ∼0.32 μm/day (Fig. 2J).

3.3. Mg implants promote initial inflammation and attenuate subsequent fibrotic encapsulation

In dedicated groups of Sprague Dawley rats, Mg implants or Ti implants were implanted in the dorsum subcutis (Fig. S1A). Pockets were surgically created by separating the panniculus carnosus muscle from the fat overlying the dorsal skeletal muscle (Fig. S1B). In accordance with a predetermined randomization scheme (Fig. 1B), each pocket either received an implant (Mg- or Ti-implanted sites) or was left without an implant (sham sites: Sham Mg or Sham Ti). Because the host response to biomaterials in this animal model typically engages an initial inflammation during the first post-operatory week followed by implant encapsulation [46], wounds were monitored from days 1–28 after surgery (Fig. 3A).

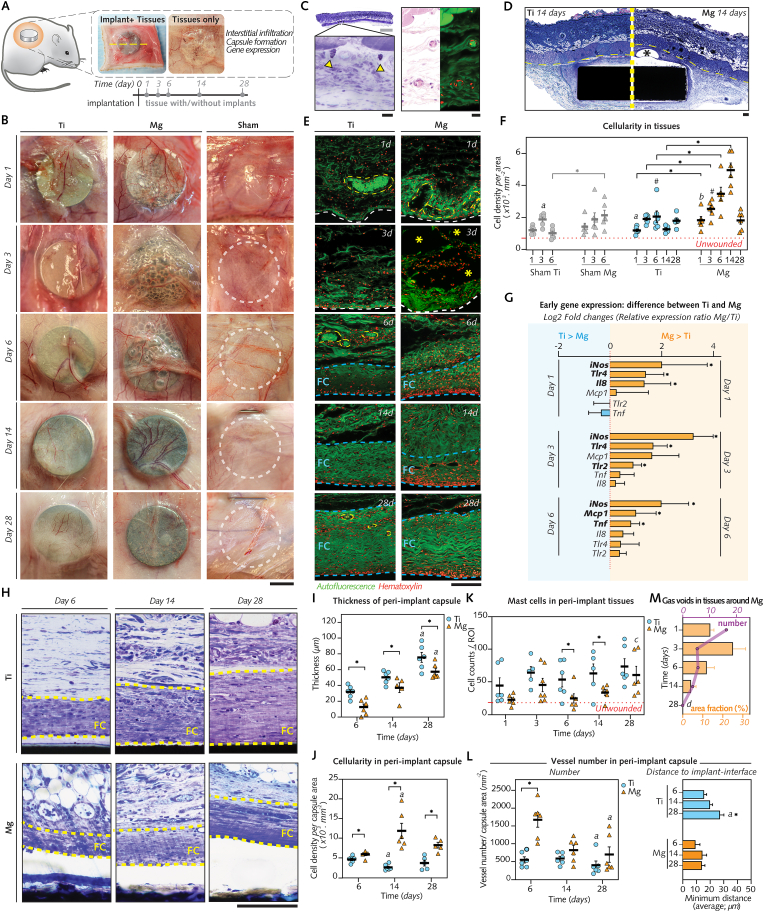

Fig. 3.

Mg implants promote early inflammation and angiogenesis but not fibrosis in tissues.

(A), Wounded tissues retrieved after 1–28 d for histology/histomorphometry (n = 5–6/group/time-point; line: section orientation) and qPCR analysis (n = 5–8/group/time-point). (B), Gross healing at re-entry of implanted and sham wounds (line). (C), Unwounded tissue histology featuring subcutaneous fascia underneath dorsal muscle [left: toluidine blue (TB) staining, arrows: mast cells; right: hematoxylin and eosin staining with autofluorescence micrograph, red: cells, green: extracellular matrix and vessels]. (D), TB-stained sections of 14 d-implants with subcutaneous fascia and muscle (line-separated). Asterisk: gas void. (E), Autofluorescence micrographs of 1–28 d-interfacial tissues (white) showing: hematoxylin-detected cells, blood vessels (yellow), and fibrous capsule (FC; blue). Asterisk: 3 d-gas voids in tissues interfacing with Mg implant (F), Cellular density in fascia (unwounded tissues: n = 6). (G), Tissue gene expression after 1–6 d (log2 relative gene expression ratio Mg/Ti). (H), Micrographs of 6–28 d-fibrous capsule (FC). (I-M), Capsule histomorphometry: thickness (I), cellular density (J), and vessel density and distance to implant-interface (L); mast cell density in fascia (K); Gas void number and relative area in Mg-implanted tissues (M).

Data are means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05 Mg versus Ti or Sham Mg versus Sham Ti; #P < 0.05 Mg or Ti versus respective sham; a: P < 0.05 versus day 6; b: P < 0.05 versus day 14; c: P < 0.05 versus days 1 and 6; d: P < 0.05 versus day 3 (area). Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test or paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Scale B = 4 mm; C: gray = 500 μm; black = 10 μm; D = 200 μm; E, H = 50 μm.

Up to postoperative day 6, (Fig. 3B) erythema and congestion, identified through dilation of the vascular arborescence in the tissue walls, remained visible in all wounded sites, particularly in those receiving Ti or Mg implants. Afterward (at 14 d and 28 d), these inflammatory signs dissipated, and tissues surrounding both implant types featured a cicatricial fibrous wall with a visible vasculature framework in close contact with the implant surface. Around Mg implants, multiple cavities, presumably related to gas evolution from Mg degradation as previously reported [47,48], were visible in the peri-implant tissue wall up to 6 d, but these cavities progressively decreased in number at 14 d and 28 d.

To further study the inflammatory response and the fibrotic encapsulation around both biomaterials, wounded tissues excised with or without associated implants were processed for histology by staining for hematoxylin and eosin (to study cellularity) and toluidine blue (to study the extracellular matrix (ECM)) (Fig. 3C–E; Figs. S3A and B). In agreement with the macroscopic observations, the initial response in tissues receiving Ti or Mg implants was marked by profuse cellular infiltration with vessel engorgement (Fig. 3E). The cellular infiltrate measured in the loose connective tissue around Mg implants was consistently denser than that in the tissue around Ti and sham sites from 1 d to 14 d (Fig. 3F). To verify the superior inflammation in tissues that received Mg implants, changes in gene levels of inflammatory markers were monitored in punches from the tissue walls around both implant types and in sham sites (Fig. 3G; Fig. S4). Between 1d and 6d, the qPCR analysis demonstrated in tissues around Mg implants a higher expression of pro-inflammatory genes (Inducible nitric oxide synthase, iNos; Tumor necrosis factor, Tnf; Toll-like receptor 2, Tlr2; and Toll-like receptor 4, Tlr4) and chemotaxis-related genes (Interleukin-8, Il8; and Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, Mcp1) than in tissues around Ti implants, before decreasing afterward (Fig. 3G; Fig. S4). This difference in mRNA levels was in line with the amplified cellular infiltration in tissues around Mg implants, thus confirming that the initial response to Mg implants involved the heightened activation of proinflammatory pathways.

Because modulation of inflammation is known to influence the subsequent tissue repair around biomaterials [49], we sought to characterize the effects of Mg implant on the fibrosis of adjacent tissues. Fibrotic encapsulation of the implants, histologically identified through the presence of abundant collagenous ECM and a cell-rich infiltrate with giant cells at the implant interface [50], was evident as early as 6 d after surgery around both biomaterials (Fig. 3E). To monitor the maturation of the fibrotic capsule over time, we quantified the cross-section thickness of peri-implant capsules (Fig. 3H and I). The capsule thickness increased from 6 d to 28 d in both groups but remained consistently thinner over time around Mg implants than around Ti implants. Concomitantly, the cell density in peri-implant capsules was invariably higher in Mg group than Ti group (Fig. 3J).

Mast cells are important actors in mediating the fibrotic reaction around implants by accumulating in adjacent tissues [51]. Thus, toluidine blue (purple)-positive mast cells (Fig. S3B) were counted in sections of the loose connective tissue around Mg and Ti implants (Fig. 3K). The number of mast cells around Mg implants was less than around Ti implants, with a significant difference at 6 d and 14 d, in line with the attenuated fibrotic encapsulation around Mg implants.

The organization of the neovascular bed at the implant interface holds a pivotal role in the healing of peri-implant tissues [52], and was therefore histomorphometrically compared between biomaterials. In comparison to Ti implants, a higher density of blood vessels was detected around Mg implants at 6 d (Fig. 3L), with the vessels possessing a greater luminal area at 6 d and 28 d (Fig. S3C) and exhibiting a smaller distance to the interface at 28 d (Fig. 2L). These differences suggested an increased vascularity around Mg implants than Ti implants.

The presence of gas voids (Fig. 3D, Fig. S3A) was another morphological feature distinct to soft tissues around Mg implants. The number and the fractional area of these voids (Fig. 3M) culminated at 1 d and at 3 d, respectively, before decreasing afterward (at 14 d and 28 d).

Taken together, the inflammatory tissue environment around Mg implants, when compared to that around Ti implants, was concomitant with an elevated accumulation of gas in soft tissues and the development of a denser vascular network and reduced fibrotic encapsulation.

3.4. The degradation of Mg implants gradually elicits the enrichment of calcium and phosphorus on their surfaces

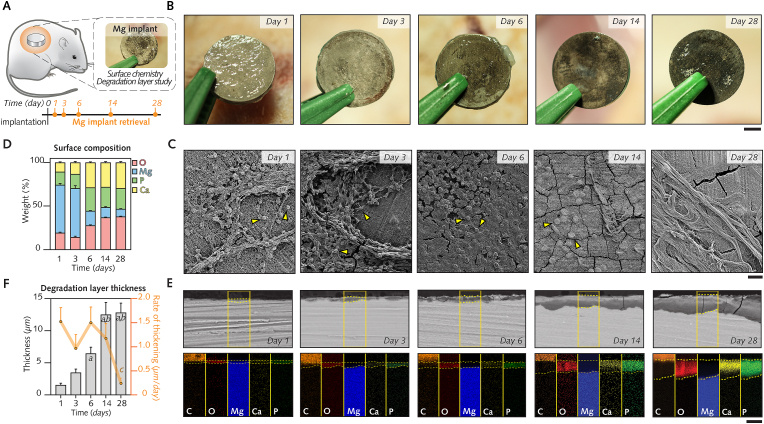

With the assumption that the degradation of Mg implants elicits a dissimilar response of soft tissue in comparison to Ti implants, we sought to characterize the degradation-induced changes of Mg implants that were excised without associated tissues from days 1–28 (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

Interface magnified: Chemical fingerprint at the surface of Mg implants is altered over time by degradation.

(A), Mg implants carefully retrieved from subcutaneous pockets for characterization of their surfaces. (B), Macroscopic observation of the Mg surface immediately following explantation after 1–28 d. (C), Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images with a secondary electron detector showing the Mg surface with implant-adherent cells (arrowheads) and extracellular matrix. (D), Time survey of Mg surface chemical composition (Mg, O, Ca and P) using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (n = 3/time-point). (E), Top: Cross-sections of the degradation layer at the Mg surface observed with SEM using a backscattered electron detector (implant and tissues embedded in plastic). Yellow dotted line: degradation layer; bottom: Maps of Mg, O, C, Ca and P in the highlighted areas in E (C is generated from embedding medium). (F), Changes over time in degradation layer thickness and in the rate of thickening per day (n = 5–6/time-point).

Data are means ± s.e.m.; a: P < 0.05 versus days 1 and 3; b: P < 0.05 versus day 6. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test. Scale B = 2 mm; C = 20 μm; E = 10 μm.

Observations of the surface of Mg implants with SE−SEM (Fig. 4C) revealed areas with a high density of cells embedded in a three-dimensional complex ECM from 1 d to 6 d, in contrast to reduced numbers of cells and extracellular deposits at 14 d and 28 d. These morphological alterations were concomitant with changes in the chemical composition of the surface of Mg implants over time, as evidenced by measurements of the relative intensities of magnesium, oxygen, calcium, and phosphorous using EDX (Fig. 4D). From days 1–28, the level of magnesium, the main element detected prior to surgery (Fig. 2E; Fig. S2B), decreased by 46%, while the level of oxygen showed a two-fold increase. This oxidation of the Mg implant surface occurred simultaneously with a distinct increase in calcium and phosphorous by 19% and 9%, respectively; these elements accounted for ∼50% of the surface chemical composition between 6 d and 28 d. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Fig. S5A) confirmed the presence of the above-described elements together with nitrogen, which was steadily detected from 1 d to 28 d.

Observations of cross-sections with scanning electron microscopy using a backscattered electron detector (BS-SEM) revealed a superficial film consisting of degradation products at the interface with the metal bulk that increased in thickness from days 1–28 (Fig. 4E). The thickness of this degradation layer steadily increased from 1.5 μm at 1 d to 13.6 μm at 28 d (Fig. 4F). Simultaneously, the chemical composition of the degradation layer also changed over time, as revealed by EDX-elemental mapping (Fig. 4E). In line with the results of Mg implant surface analysis, the incorporation of calcium and phosphorous in the degradation layer was visible as early as after 1 d. However, the preferential accumulation of calcium and phosphorous in the outer regions was clear starting from day 6 (Fig. 4E; Fig. S5B). These elements combined with oxygen, which was evenly distributed over the degradation layer cross-sections, resulting in an evident outer calcium-, phosphorus-, and oxygen-rich layer at 14 d and 28 d. In contrast, the inner regions of the degradation layer exhibited higher magnesium and oxygen contents at the expense of decreased calcium and phosphorous contents at 14 d and 28 d (Fig. 4E; Fig. S5B). Together with the slower thickening after 14 d (Fig. 4F), these findings demonstrate that the maturation of the degradation layer at the surface of Mg implants occurs simultaneously with changes in the topographical distribution of the chemical elements, whereby calcium and phosphorous are more concentrated at the tissue interface.

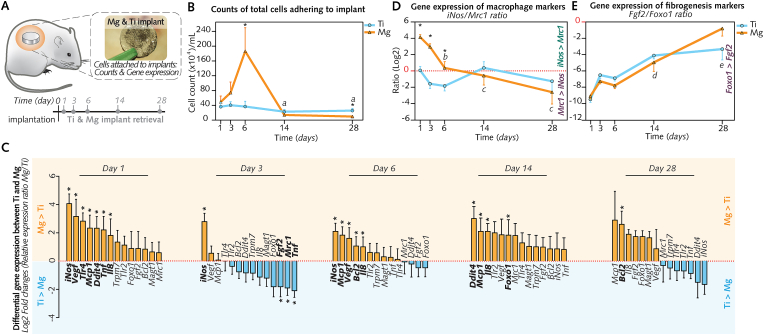

3.5. Alteration of the Mg implant surface occurs with concomitant regulation of the number of implant-adherent cells and gene expression in these cells

The surface properties of implants are a pivotal factor that influences the host response [53]. The cells adherent to the implant surface, which have undergone migration, maturation and adhesion, directly sense these properties to mediate changes of their number, and of their gene expression [34,54]. We therefore harvested the implant-adherent cells to determine whether their counts and their mRNA levels are influenced by the degradation-induced changes on the surface of Mg implants in comparison to Ti implants from days to 1 to 28 (Fig. 5A). While cytometry-counted cells (Fig. 5B) on Ti implant surface remained comparable at all time points, the number of Mg implant-adherent cells sharply increased from 1 d to culminate at 6 d (∼5-fold higher than cell number at the surface of Ti implants), thereafter decreasing toward 14 d and 28 d. These quantitative differences were in agreement with morphological observations (Fig. S6) showing, from 1 d to 6 d, the ECM- and cell-rich surface of Mg implants, in contrast with the inconsistent cellular presence and small amounts of extracellular material at the surface of Ti implants.

Fig. 5.

Interface magnified: Cells adherent to the implant surfaces, their enumeration and gene expression.

(A), Ti and Mg implants were collected from subcutaneous pockets to count cells adherent to their surface and to analyze their gene expression. (B), Counts of total implant-adherent cells (n = 6–7/group/time-point). (C), Differential gene expression between Mg and Ti (log2 of the relative gene expression ratio Mg/Ti; n = 8/group/time-point). (D-E), Changes over time of the gene expression ratios: iNos (M1-macrophage marker) to Mrc1 (M2-macrophage marker) (D), and Fgf2 (fibrogenesis marker) to Foxo1 (antifibrotic marker) (E). Log2 of relative gene expression ratios are shown (n = 8/group/time-point).

Data are means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05 Mg versus Ti; a: P < 0.05 versus days 1, 3, and 6 in Mg; b: P < 0.05 versus day 1 in Mg; c:P < 0.05 versus days 1 and 3 in Mg. d:P < 0.05 versus day 1 in Mg and Ti. e:P < 0.05 versus days 1 and 6 d in Mg and Ti. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test.

qPCR analysis of implant-adherent cells was conducted using a panel of 14 genes of interest (Table S2) that mark for major events of the wound healing such as Tnf, Il8, Mcp1, Tlr4 and Tlr2 for inflammation, iNos (proinflammatory macrophages) and Mrc1 (prohealing macrophages) for macrophage polarization, Vegf for angiogenesis, Fgf2 for fibrogenesis, and Foxo1 as an antifibrotic marker. Pro-apoptotic gene Ddit4 and anti-apoptotic gene Bcl2 were also included to explore cell death pathways, in addition to Mg2+ channel genes Trpm7 and Magt1, suggested to be involved in the cellular response to Mg-based biomaterials [55].

Between 1 d and 6 d, inflammatory signature genes (iNos, Tnf, Il8, Mcp1 and Tlr4) remained highly expressed by cells adherent to Mg implants in comparison to cells adherent to Ti implants (Fig. 5C; Fig. S7), which is in agreement with the pronounced migration of cells to the Mg implant surface. For some chemotaxis genes (i.e., Mcp1, Il8), this upregulation of mRNA levels at the surface of Mg implants extended to 14 d. Cells adherent to Mg implants also featured a higher expression of Vegf up to 6 d in comparison to cells adherent to Ti implant surface (Fig. 5C; Fig. S7), in support of the superior vascular supply of the peri-implant fibrous capsule around Mg implants in comparison to Ti implants (Fig. 3L; Fig. S3C). Other genes that were upregulated on the surface of Mg implants in comparison to Ti implant surface consisted of Ddit4 (at 1 d and 14 d) and Bcl2 (at 6 d and 28 d) (Fig. 5C; Fig. S7), suggesting that the gene regulation of apoptotic pathways in Mg implant-adherent cells followed a sequence early proapoptosis–late antiapoptosis. Fibrosis-related genes also featured differences between Mg and Ti implants: antifibrotic marker Foxo1 was upregulated at 14 d at the surface of Mg implants, whereas profibrotic marker Fgf2 featured a superior expression at Ti implants as early as 3 d; however, the ratio Fgf2/Foxo1 was not different between both biomaterials. Further supporting the early gene activation of fibrosis at the surface of Ti implants was the elevated expression of prohealing macrophage gene Mrc1 at 3 d along with the ratio iNos/Mrc1 (Fig. 5D), that was shifted toward Mrc1 gene from days 1–28. In contrast, iNos/Mrc1 ratio for cells adherent to Mg implants was consistently shifted toward iNos gene between 1 d and 6 d, before decreasing and switching to a pattern similar to that of cells adherent at Ti implants (that is shifted toward Mrc1 gene) at 14 d and 28 d. These trends indicated a differential gene regulation of macrophage polarization before and after 6 d in cells adherent to Mg implant but not Ti implants. No differences between Mg and Ti implants were observed for gene markers of Mg2+ channels Trmp7 and Magt1 (Fig. S7).

In summary, cytometry and qPCR findings suggested that the surface of Mg implants attracted higher number of cells and promoted the expression of inflammatory and neoangiogenesis genes between 1 d and 6 d in comparison to cells adherent to Ti implants. Afterward, the degradation-induced changes of Mg implant surface were accompanied by a reduced cellular migration and a downregulation of inflammatory genes together with an increased expression of antifibrotic gene Foxo1.

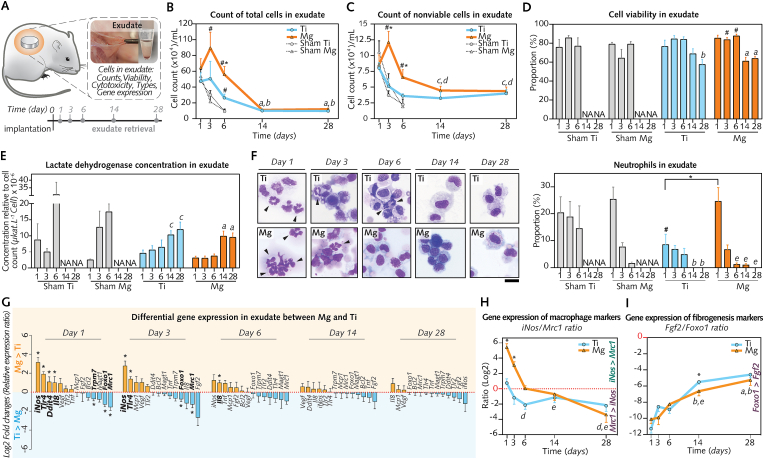

3.6. The inflammation in the exudate around Mg implants is amplified but transient and does not alter the cell viability

Having evidenced a pronounced proinflammatory response in cells directly adhering on the surface of Mg implants in comparison to Ti implants, we next turned to the adjacent exudate compartment and asked whether Mg implant degradation generates a cytotoxic effect. Cell death is pivotal to the initiation of the immune response to wear metallic particles and ions leading to peri-implant soft tissue damage [26,56]. Thus, we characterized the contents of the exudate surrounding both implant types, which was obtained by the lavage of the pockets (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Interface magnified: Cells in the peri-implant exudate, their enumeration, types, viability and gene expression.

(A), The exudate was assigned to analyses of cells and their gene expression (n = 8/group/time-point). (B), Counts of total cells. (C), Counts of nonviable cells. (D), Proportions of viable cells. (E), Relative cytotoxicity in exudate. (F), Proportions of neutrophils (right; n = 5–7/group/time-point) and representative micrographs from cytospin preparations (left; arrowheads: neutrophils). (G), Differential gene expression between Mg and Ti. (log2 of the relative gene expression ratio Mg/Ti; n = 8/group/time-point). (H– I), Changes over time of the gene expression ratios: iNos (M1-macrophage marker) to Mrc1 (M2-macrophage marker) (H), and Fgf2 (fibrogenesis marker) to Foxo1 (antifibrotic marker) (I). Log2 of relative gene expression ratios are shown (n = 8/group/time-point).

Data are means ± s.e.m.; NA: Not analyzed. Exudates were not collected from Sham Ti and Sham Mg at days 14 and 28 (wounds were closed). *P < 0.05 Mg versus Ti; #P < 0.05 Mg or Ti versus respective sham; a: P < 0.05 versus days 1, 3, and 6 in Mg; b: P < 0.05 versus days 1, 3, and 6 in Ti; c: P < 0.05 versus day 3 in Mg; d: P < 0.05 versus day 1 in Ti; e: P < 0.05 versus days 1 and 3 in Mg. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test or paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Scale F = 20 μm.

The total number of cells (Fig. 6B) and nonviable cells (Fig. 6C) were counted using cytometry in exudate samples to calculate the proportion of viable cells (Fig. 6D). The total counts of cells (Fig. 6B) in the exudate around Mg implants increased from 1 d to peak at 3 d before steadily decreasing until 28 d. In comparison to the exudate around Ti implants or in Sham Mg, a higher number of cells was detected in the exudate around Mg implants between 1 d and 6 d, in line with the counts of implant-adherent cells (Fig. 5B). These changes over time in total cell counts were very similar to nonviable cell counts (Fig. 6C) in exudate samples around both implant types from days 1–28. However, despite the increased number of nonviable cells around Mg implant, cell viability fractions in exudate around both biomaterials were comparable (Fig. 6D). In exudate around Mg and Ti implants, the viable cell fraction ranged between 76% and 87% from 1 d to 6 d before decreasing at 14 d and 28 d to a range 69%–57%. To verify these cell viability results, the cytotoxicity in the same exudate specimens was also determined by measuring the concentrations of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), an enzyme released from cells upon damage of their membrane [57]. Relative LDH concentration (Fig. 6E) was similar from days 1–6 in exudate around Mg or Ti implants, before increasing at 14 d and 28 d without difference between the biomaterials. The agreement between cytotoxicity and cell viability findings was further confirmed by their significant association (Fig. S8A), strengthening the conclusion that Mg implants did not preclude the viability of cells recruited to the interface.

Beyond their function as the first line of cells of innate immunity, prolonged recruitment of neutrophils is linked with a sustained inflammation in response to wear particles and ions from metallic implants [26]. Having observed an elevated expression of chemotaxis Il8 at the surface of Mg implants, we visualized cell types recruited to the wounded sites using cytospin histological preparations from the exudate samples. While mononuclear cells predominated in both groups and at all time points (Fig. 6F; Fig. S8B), higher neutrophil counts were detected around Mg implants than around Ti implants at 1 d; though, neutrophils did not exceed 30% of the total cells. Noticeably, after 1 d, the fraction of neutrophils around Mg implants substantially decreased to levels comparable over time with those around Ti implants (Fig. 6F).

mRNA levels of cells collected in exudate specimens (Fig. 6G, Fig. S9) were also measured using the same gene panel as for the implant-adherent cells (Table S2). Differences between biomaterials were observed only from days 1–6. On the one hand, cells in exudate around Mg implants featured the upregulation of only few inflammatory and chemotaxis genes in comparison to that around Ti implants: Tlr4, Il8, and most noticeably iNos (Fig. 6G); overall, the elevated expression of the inflammatory signature genes at the interface with Mg implants was less evident in exudate cells than in implant-adherent cells (Fig. 5C). Of note, iNos consistently featured at 1 d, at 3 d, and occasionally at 6 d, the highest difference between Mg and Ti implants at the 3 compartments: implant surface (Fig. 5C), exudate (Fig. 6G), and soft tissues proper (Fig. 3G). Exudate around Mg implants also displayed an upregulation at 1 d of pro-apoptotic gene Ddit4 in comparison to exudate around Ti implants. However, this expression difference between biomaterials was discrete compared to that for implant-adherent cells, and partially confirm the cell viability and cytotoxicity findings. On the other hand, cells in exudate around Ti implants featured a higher expression of Trpm7 at 1 d in comparison to that around Mg implants, indicating a differential gene regulation of this Mg2+ channel. Foxo1 and Mrc1 gene expression were also higher in exudate around Ti implants than that around Mg implants at 1 d and 3 d. The first gene suggested a prompt antifibrotic modulation in exudate around Ti implants. The second gene reflected the early activation of prohealing macrophage in exudate around Ti implants as observed for implant-adherent cells. Most notably, the ratio iNos/Mrc1 (Fig. 6H) for both biomaterials featured kinetics very similar for exudate cells to that for implant-adherent cells, with an evident shift toward iNos from days 1–6 in exudate around Mg implants. Fgf2/Foxo1 ratio (Fig. 6I) was smaller at 14 d in exudate around Mg implants, confirming the 14 d-antifibrotic gene activation as observed for cells adherent to Mg implants.

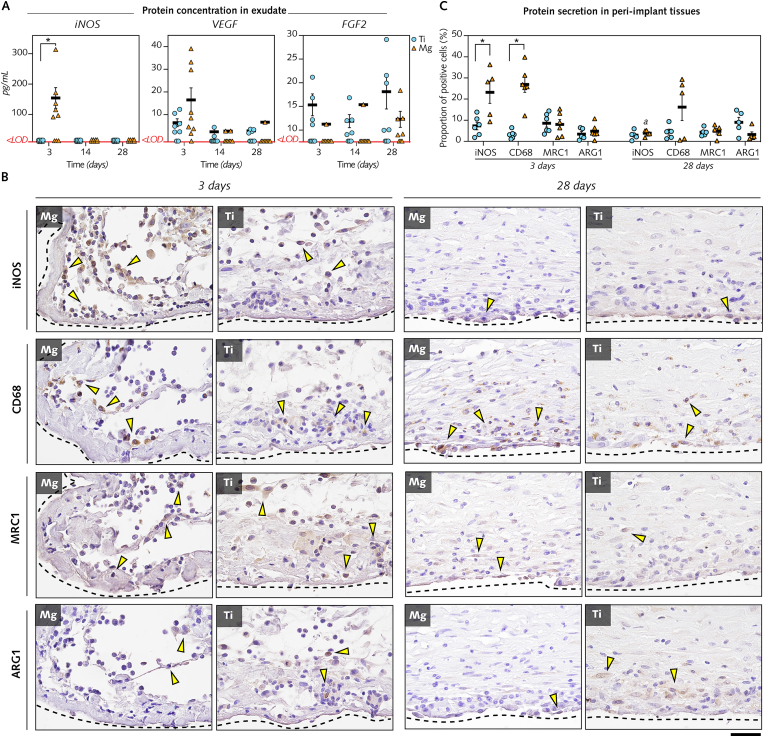

To determine the expression of selected proteins, the concentrations of iNOS, VEGF, and FGF2 were measured in exudate supernatants at 3 d, 14 d and 28 d (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Interface magnified: Detection of protein secretion in exudates and immunoreactive cells in peri-implant tissues in response to Mg implants versus Ti implants.

(A), The concentrations of iNOS, VEGF, and FGF2 were quantified using ELISA in exudate samples collected around Mg implants and Ti implants at 3 d, 14 d, and 28 d (n = 8–9/time point/group). <LOD: measurement below the limit of detection. (B), Immunohistochemistry to detect cells positive to M1 macrophage subtype markers (iNOS, CD68), and M2 macrophage subtype markers (MRC1, ARG1) in tissues interfacing with Mg and Ti implants at 3 d and 28 d. Black-dotted lines: interface with Mg and Ti implants. Arrowheads: indicate some of the positive cells. (C), Quantification of cells positive for iNOS, CD68, MRC1, and ARG1 at 3 d and 28 d in tissues within a distance of 200 μm from the interface with Mg implant and Ti implants (n = 5–6/time point/group; proportion of positive cells in an average of ∼10 000 cells/region of interest in each section).

Data are mean ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05 Mg versus Ti; a: P < 0.05 day 3 versus day 28 in Mg. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test. Scale B = 20 μm.

While no differences existed between biomaterials in VEGF and FGF2 exudate concentrations, iNOS concentration was considerably higher at 3 d in exudate around Mg implants compared with Ti implants. Further supporting the major role of proinflammatory macrophages at 3 d in response to Mg implants, immunohistochemistry of peri-implant tissues (Fig. 7B; Fig. 7C) demonstrated a 3-fold and an 8-fold higher detection of cells with markers of proinflammatory macrophages (subtype M1) iNOS and CD68, respectively, at the interface with Mg implants in comparison to Ti implants at 3 d. No differences between biomaterials were found at 3 d and 28 d in the detection of cells positive for MRC1 and Arginase-1 (ARG1) that mark for the prohealing macrophages (subtype M2).

In conclusion, between 1 d and 6 d, vigorous cell recruitment, including neutrophils, and upregulation of inflammatory pathways, particularly through elevated gene levels and protein secretion of iNOS, were evident in the exudate and peri-implant tissue around Mg implants in comparison to that around Ti implants. However, Mg implants did not exert cytotoxic effects, and the amplified inflammation around these implants markedly subsided at 14 d and 28 d.

3.7. The temporal changes of Mg implant degradation modulate markers of early inflammation and subsequent tissue repair

To examine the relationship between the changes over time of Mg implant degradation and that of the cellular and molecular response, we monitored Mg2+ levels in the same exudate samples used to characterize the cell count, cell viability, cytotoxicity, and gene expression levels (Fig. 8A).

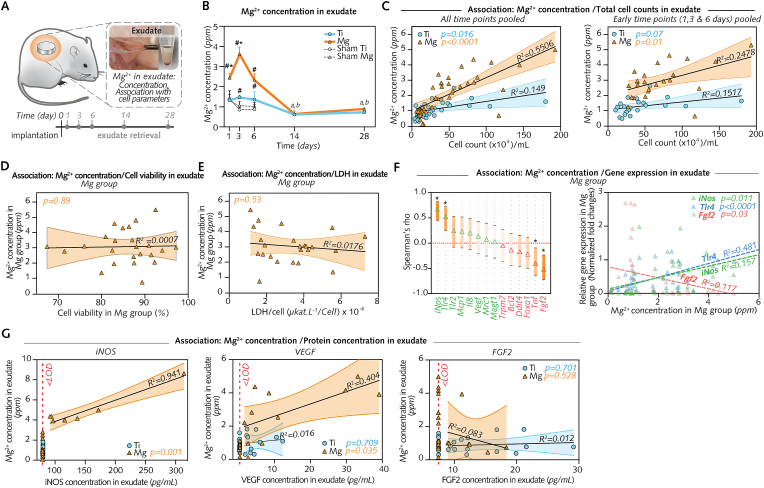

Fig. 8.

Interface magnified: Mg degradation sequentially tunes early inflammation and subsequent tissue repair.

(A), Mg2+ concentration was measured and compared to cell counts, gene expression, and protein concentrations in the same samples (n = 7–8/group/time-point). (B), Mg2+ concentration measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). (C), Linear regression of Mg2+ concentration and total cell counts (Left: Data from all time points pooled; Right: Data from 1 d, 3 d and 6 d pooled; 95% confidence intervals are shown). (D), Linear regression of Mg2+ concentration and cell viability in exudate around Mg at 1 d, 3 d and 6 d (data pooled; 95% confidence intervals). (E), Linear regression of Mg2+ concentration and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in exudate around Mg at 1 d, 3 d and 6 d (data pooled; 95% confidence intervals). (F), Spearman correlation of Mg2+ concentration and gene expression (left; *P < 0.01; 95% confidence intervals) and respective linear regression (right) confirming significant associations for genes iNos, Tlr4, and Fgf2. (G), Linear regression of Mg2+ concentration and protein concentration in exudate around Mg at 3 d, 14 d, and 28 d (data pooled; 95% confidence intervals) showing a significant association between Mg2+ concentration and iNOS and VEGF, respectively, at the protein level. <LOD: measurement below the limit of detection.

Data are mean ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05 Mg versus Ti; #P < 0.05 Mg or Ti versus respective sham wounds; a: P < 0.05 versus days 1, 3, and 6 in Mg; b: P < 0.05 versus days 1, 3, and 6 in Ti. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test or paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

First, Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 8B) was measured with inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). The mean concentration in the exudate around Mg implants peaked at 3 d, was 1.7- and 2.5-fold higher than that around Ti implants at 1 d and 3 d, respectively, and was 1.8- to 3.4-fold higher than that around Sham Mg from days 1–6. Thereafter, this concentration in exudate around Mg implants markedly decreased until 14 d and 28 d. Noting that this pattern between days 1 and 28 of Mg2+ concentration was in line with that of total cell counts in exudate around Mg implants (Fig. 6B), a regression analysis (Fig. 8C) was performed to verify the relationship between the variables. We found a positive association [at early time points when the Mg2+ concentration was higher (i.e., 1 d, 3 d, and 6 d) (Fig. 8C, right) as well as when data from all time points were pooled (Fig. 8C, left)], validating that the cell counts were linked to the Mg2+ concentrations in exudate around Mg implants, but not around Ti implants or in sham wounds (Fig. S10A). Furthermore, we questioned if a similar relationship existed in exudate around Mg implants between Mg2+ levels and cell viability (Fig. 8D) or cytotoxicity (Fig. 8E). Regression analyses (Fig. 8D and E) showed, however, that such associations did not exist. Overall, these findings indicated that, at the interface with Mg implants, the early increase in the Mg2+ concentration was associated with an increase in the number of recruited cells; however, it did not affect the viability of these cells.

Last, we aimed to verify if a relationship existed between the changes over time of Mg2+ concentration and that of gene expression (Fig. 6G, Fig. S9) and of protein concentration (Fig. 7A) in exudate around Mg implants. Among all genes (Table S2), both correlation (Fig. 8F, left) and regression analysis (Fig. 8F, right) identified an association only for proinflammatory genes iNos (positive association), and Tlr4 (positive association), and for profibrotic gene Fgf2 (negative association). At the protein level (Fig. 8G), Mg2+ concentration featured a strong positive association with iNOS concentration, and a positive association with VEGF. Together, these results suggest that the changes over time of Mg2+ sequentially modulate the initial acute yet transient and noncytotoxic reaction up to 6 d to enable the subsequent repair around Mg implants.

3.8. Mg implant degradation modulates the expression of markers of inflammation and tissue repair beyond the interfacial tissues

In this study, Sham Mg and Sham Ti sites consisted of pockets that were wounded at a distance of ∼2 cm from Mg- and Ti-implanted pockets, respectively (Fig. 9A).

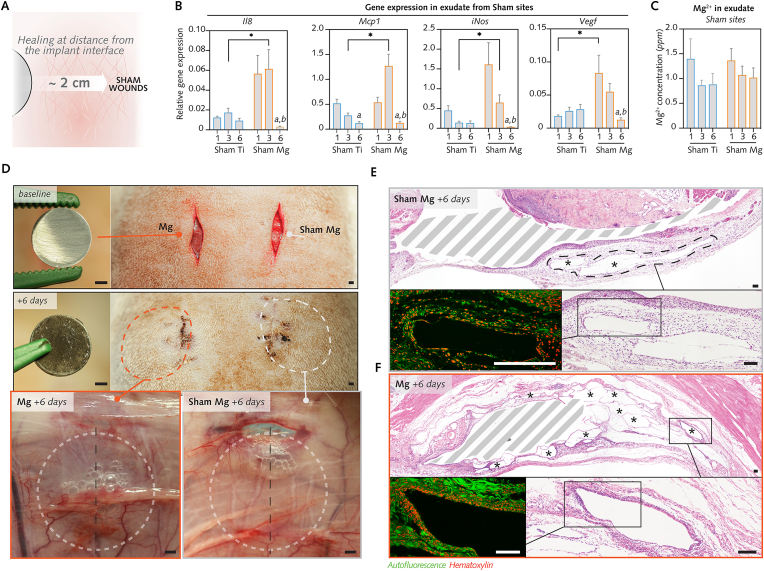

Fig. 9.

Changes over time of the cellular and molecular alterations in sham wounds.

(A), To verify whether Mg degradation influences healing in Sham Mg, the cellular and molecular parameters in the exudate were compared between Sham Ti and Sham Mg after 1–6 d. (B), Relative gene expression in sham wounds (n = 8/group/time-point). (C), Mg2+ concentrations in exudate from sham wounds (n = 7–8/group/time-point). (D), Clinical photographs display the implantation of a Mg implant and sham wounding (top panel). At postsurgery day 6, wounds in the same rat were re-entered for retrieval of the implant (middle panel), the exudate and the tissues (lower panel). The fascia in Sham Mg wounds featured voids comparable to those in tissues around Mg implant. (E–F), Histological sections of wounds in D exhibiting voids in tissue walls in Sham Mg similar to gas voids around Mg implant in the same rat. Bottom panels in E and F (hematoxylin and eosin staining with autofluorescence micrograph, red: cells, green: extracellular matrix and vessels) show magnified areas of the voids (asterisks in upper panels ofEandF) separated by thin walls of extracellular matrix and with a higher cellularity at their boundaries, similar to Mg-implanted tissues (F,bottom left). Dashed areas indicate surgically created pockets with or without implants.

Data are means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05 Sham Mg versus Sham Ti; a: P < 0.05 versus day 1; b: P < 0.05 versus day 3. Unpaired Mann-Whitney U test. Scale D = 2 mm; E, F = 100 μm.

We noticed from the histomorphometrical analysis of soft tissues (Fig. 3F) that Sham Mg featured a higher cellular infiltration at 6 d than that in Sham Ti. We further compared the healing between these groups by examining the cell counts (Fig. 6B) and mRNA levels (Fig. 9B) in exudates retrieved by lavage of Sham Mg and Sham Ti pockets between 1 d and 6 d. While cell counts were statistically comparable between both groups, the qPCR analysis demonstrated that the Sham Mg group exhibited higher expression of the chemotaxis genes Mcp1 (at 3 d) and Il8 (at 3 d), the proinflammatory macrophage gene iNos (at 3 d), and the angiogenesis gene Vegf (at 1 d) in comparison to the Sham Ti group (Fig. 9B). Importantly, this rise in gene expression was transient, ending at 6 d, and analogous to findings in exudates from sites receiving Mg implants. Thus, although not receiving Mg implants, Sham Mg group featured a gene expression different from that of Sham Ti group, but with notable similarities to the patterns of gene expression in Mg implant group.

Next, in order to determine the relationship with the distinct gene expression in the distant Sham Mg pockets, we determined Mg2+ concentration in exudate from Sham Mg and Sham Ti groups (Fig. 9C), yet without detecting a significant difference between both groups. Furthermore, Mg2+ concentration in the Sham Mg group did not reveal a significant association with the cell count (Fig. S10A) or with mRNA levels (Fig. S10B), thus assigning that a role of Mg2+ from Mg implant sites for cell behaviour in distant sham sites is less likely. However, macroscopic (Fig. 9D) and microscopic observations (Fig. 9E and F) provided evidence of voids in the tissues sampled in the Sham Mg group. In histological sections, the tissues surrounding these voids (Fig. 9E) exhibited greater cellular infiltration, showing similarities with the gas voids detected in tissues around Mg implants (Fig. 9F). In summary, these findings inferred that the gas released from the Mg implant might contribute to the elevation of the initial inflammatory response in the distant Sham Mg pockets.

4. Discussion

Magnesium is a prime example of a biodegradable material which has been introduced as an alternative to conventional non-degradable materials in orthopaedics and cardiovascular medicine. While Mg and biodegradable Mg implants are classically presented to hold anti-inflammatory properties, the inflammation of soft tissues around Mg orthopedic implants is an elusive clinical event, and questions the safety and the biocompatibility of metallic degradation byproducts deposited in the adjacent tissues. Using a soft tissue rat model, we demonstrate that an early amplified inflammation is inevitable and is initiated by the burst release of degradation products from Mg implants, yet without a cytotoxic effect. Thereafter, however, the slower degradation modulates the acute response and enables an improved vascular supply and reduced fibrosis of peri-implant soft tissues, therefore attenuating FBR in comparison to the state-of-art nondegradable implants made of Ti.

A pivotal feature of the initial response to Mg implants was the early and marked increase in inflammation in comparison to that upon implantation with Ti. Our findings are in opposition to the notion of anti-inflammatory properties assigned to Mg implants. This assumption mainly stems from the literature demonstrating the aptitude of Mg2+ supplementation to abrogate hypomagnesemia-related inflammation [58], or from previous in vitro studies reporting an anti-inflammatory effect in immune cells treated with Mg2+ [28,30]. The present study demonstrates in vivo that the initial profuse release of Mg2+ from Mg implants, culminating at 3 d, causes a pronounced cellular influx at the implant-interface. Such a marked chemotaxis in response to Mg degradation might be primarily ascribed to chemokines such as Il8 and Mcp1 which featured an upregulation of their gene expression. Moreover, Mg2+, alike other divalent anions such as Ca2+, can also potentiate chemotaxis in a dose-dependent-fashion [59]. Suggested mechanisms behind Mg2+-induced cell migration include the activation of downstream pathways of receptors such as G-protein receptor [60] and calcium-sensing receptor CaSR [61], along with the disassembly of intercellular junction proteins thus enabling cellular motility [62]. Chemotaxis promotion is also reported during the early response to Cu2+-releasing implants in a soft tissue model identical to the animal model used in this study. Up to 3 d, the proinflammatory response at the interface with copper – mediated by: neutrophil recruitment [33], proinflammatory cytokine release [33,35], and activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) signaling pathway [63] – was sustained over time in contrast with a transient inflammation in control sites implanted with Ti. Our correlation and regression analyses, identifying a robust association linking Mg2+ release at the interface to chemotaxis, to the expression of genes iNos and Tlr4 and to the secretion of iNOS protein, further supported that Mg implants elicit an initial proinflammatory reaction at the immediate tissue milieu. Such a response, however, should not be solely ascribed to Mg2+ and a role of other Mg degradation byproducts cannot be excluded.

Gas accumulation in soft tissues also accompanied the amplified inflammatory response to Mg implants in our study, and is presumed to result from hydrogen production by the corrosion reaction Mg+2H2O→Mg2++2OH−+H2 [3]. While an anti-inflammatory benefit is attributed to exogenous hydrogen administration [64], gas accumulation in tissues from Mg implants has been assumed to preclude the healing of Mg implants [65], advocating the removal of the gaseous voids by puncture procedure in some animal studies [4,66]. An explanation for this contradiction might be the gas composition inside tissue voids around Mg implants. In fact, hydrogen is believed to be only a minor component of these gaseous structures, due to its fast escape into the body fluid, at the expense of a higher concentration of other gases such as nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide [67]. Of importance is also the microscale alteration of pH near the Mg implant surface, resulting from hydroxide release. The initial and moderate alkalinization during Mg implant degradation, as suggested herein by the immersion tests, might also influence the cellular behavior including viability, proliferation, and differentiation [68,69]. In this study, Sham Mg wounds, which were at ∼2 cm-distance from Mg implants, featured elevated levels of proinflammatory and angiogenesis genes. The macroscopic and histological evidence of voids resembling those detected around Mg implants, together with the comparable Mg2+ concentration with Sham Ti, evoked a plausible proinflammatory effect by gas in Sham Mg. This assumption is supported by the propagation capacity of the gas produced by Mg degradation which is reported in soft tissue [47,67]. Whether the gaseous composition or the mechanical cues by these voids might tune the response of nearby cells toward inflammation is yet to be elucidated.

The finding that the conspicuous inflammation in soft tissues around Mg implants was not associated with an amplified cellular death is of critical importance. Cytotoxicity triggered by wear particles and ions holds, indeed, a chief role in the immune cascade behind soft tissue damage in patients with e.g. cobalt-chromium implants [26]. Instead, the comparable cell viability and cytotoxicity that were demonstrated at the interface for Mg and Ti implants, and in sham wounds support the assumption that the increased inflammation by Mg implants does not detain the deleterious effects documented in the soft tissue reaction to wear byproducts from cobalt-chromium implants [56]. Although the mRNA levels of apoptotic marker Ddit4 were elevated at the Mg implant-interface, the expression of this gene is also known to be regulated by hypoxia [70] – a condition typical of the degradation process at Mg implant surface [71].

From 6 d, the subside of the initial inflammation and the assembly of the fibrous capsule around Mg implants overlapped with noticeable alterations in Mg degradation dynamics. To recapitulate, the decrease in Mg2+ concentration at the interface, the reduction in gas voids in soft tissues, and the enrichment in calcium and phosphorus at Mg implant surface indicated the deceleration of Mg implant degradation. That a calcium-phosphorous-rich superficial layer conveys timely degradation protection to Mg implants, as we showed in soft tissues, corroborates similar observations in bone [4,8] and in vascular walls [72]. Upon contact with body fluids, Mg degrades via a series of anodic and cathodic reactions that consume dissolved oxygen and produce oxides and hydroxides along with hydrogen gas [3]. Although protective layers comprising Mg oxide [MgO] and Mg hydroxide [Mg(OH2)] form on the implant surface, anions in body fluids break up the oxide phases of the covering layers, thus maintaining the degradation process [3]. As a consequence of the local alkalization that accompanies Mg degradation, Ca2+ and PO43− in body fluids precipitate on the surface of the degrading metal. In turn, this calcium-phosphorous-rich layer, that was established at Mg implant surface after 6 d, would act as a barrier against oxygen transport, and stabilizes the degradation process.

Interestingly, the shift in degradation kinetics was intimately linked to the transition from a proinflammatory to a prohealing response. Illustrating this biphasic kinetic response at Mg implant microenvironment were the changes over time of iNOS both at the gene and the protein level. iNOS featured the strongest upregulation in mRNA levels between 1 d and 6 d, and a robust protein detection at 3 d in response to Mg implants, and implies the vigorous initial activation of proinflammatory macrophage [73], as supported by the elevated presence of CD68-positive cells in the tissue around Mg implants. Then, after 6 d, mRNA and protein levels of iNOS dramatically declined together with iNos/Mrc1 gene expression ratio, suggesting a switch toward activation of prohealing macrophages. This behavioral switching of macrophages is an important milestone in the course of wound healing around biomaterials, and drives the progression from the initial proinflammatory step toward the reparative phase [74]. However, if persistent, the activation of proinflammatory macrophages due to the prolonged release of Mg2+ precludes tissue repair as reported in bone defects [75]. Therefore, the transient proinflammatory response, intimately linked to the kinetics of Mg implant degradation and to the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species at the implant microenvironment [76], is a key event for the subsequent proper tissue repair. Such a sequence in tissues around Mg implants fostered neovascularization and mitigated peri-implant fibrosis. Both features were demonstrated in this study by the morphology of the cicatricial capsule and by the molecular regulation of markers of angiogenesis (Vegf), fibrogenesis (Fgf2) and antifibrosis (Foxo1) at the Mg implant-interface. A lack of vascularization and an excessive fibrotic encapsulation of biomaterials are two hallmark components of the FBR, both intricately tuned by inflammation [77]. The promotion of inflammation is a strategy that has shown merit in improving neovascularization in various wound healing models [78], mainly through proinflammatory macrophages that produce high amounts of pro-angiogenic factors [79]. Among these, VEGF, in particular, is a key factor in initiating and driving vessel sprouting during the initial inflammatory stage [80]. If sustained, however, an overt inflammatory state becomes deleterious and leads to an excessive fibrotic response [77], as observed around Cu2+-releasing implants that sustained soft tissue inflammation in the same rat model as herein [41]. At Mg implant surface, the 14 d-upregulation of Foxo1 gene expression, key to the apoptosis of profibrogenic myofibroblasts [81], further testifies in favor of the subsequent antifibrotic effect. The attenuation of fibrous encapsulation was also reported in mice 28 d following implantation with Mg particles-embedded polymer nano-fiber meshes subsequent to an initial inflammatory response [82]. Collectively, the timely subside of inflammation is postulated to account for the lack of aberrant fibrosis around Mg implants, and underpins the translational potential of their immunomodulatory effect.

From a clinical perspective, an improved vascularization without excessive fibrosis is coveted not only in soft tissues that overlay Mg osteosynthesis systems but also for other clinical applications of Mg-based biomaterials. Prime among these are clinically-approved Mg-based vascular stents. Due to their fast degradation, these implants only partially succeed in preventing long-term re-narrowing (i.e., restenosis) of diseased vessels in patients [83], although being the main incentive behind using bioresorbable stents instead of their non-resorbable analogs. Translating the antifibrotic effect demonstrated herein in soft tissue, Mg-based vascular stents that are tailored to degrade slower might mitigate the unwanted fibrosis-linked restenosis in treated vessels, although a response discrepancy inherent to differences between tissues remains plausible.