ABSTRACT

Flexible organic solar cells (FOSCs) are one of the most promising power sources for aerospace aircraft due to their attractive advantages with high power-per-weight ratio and excellent mechanical flexibility. Understanding the performance and stability of high-performance FOSCs is essential for the further development of FOSCs for aerospace applications. In this paper, after systematic investigations on the performance of the state-of-the-art high-performance solar cells under thermal cycle and intensive UV irradiation conditions, in situ performance and stability tests of the solar cells in the 35 km stratospheric environment were carried out through a high-altitude balloon uploading. The encapsulated FOSCs with an area of 0.64 cm2 gave the highest power density of 15.26 mW/cm2 and an efficiency over 11%, corresponding to a power-per-weight ratio of over 3.32 kW/kg. More importantly, the cells showed stable power output during the 3-h continuous flight at 35 km and only 10% performance decay after return to the lab, suggesting promising stability of the FOSCs in the stratospheric environment.

Keywords: flexible organic solar cells, stratospheric environment, 35-km altitude, thermal cycle, reliability

Flexible organic solar cell was launched to 35 km stratosphere through a high-altitude balloon, showing a high specific power ratio of 3.32 kW/kg and very good stability.

INTRODUCTION

Near-space aircraft and high-altitude pseudo satellites in the stratosphere have a wide application in environmental monitoring, disaster relief and mitigation, agricultural and forestry monitoring, resource exploration, and communication [1]. Since they are remote from the earth, solar energy is the best energy source for near-space aircraft and high-altitude pseudo satellites. Unlike on earth, solar panels for space application should have a high power-per-weight ratio with excellent reliability in the stratospheric environment, which is essential in reducing the overall weight of the power system and consequently increasing the payload and endurance of the aircraft. Therefore, photovoltaic technologies with high power-per-weight ratio, including ultrathin silicon solar cells [2,3] and III-V multijunction cells are mostly included for this purpose [4]. In comparison with these mature solar cell technologies, the emerging nano-thin film solar cells, including organic solar cells (OSCs) and perovskite solar cells (PeroSC) are very attractive for aerospace applications owing to the features of high power-per-weight ratio and excellent flexibility [5,6] that originate from their ultrathin layered structure. Conceptual proofs of the performance of OSC and PeroSC at stratospheric and satellite altitudes were carried out by Cardinaletti et al. [7], Zhu et al. [8] and Müller-Bushbaum et al. [9] using high-altitude balloons at 35 km or a rocket flight at 240 km, respectively. Although most of the cells for the space tests were rigid ITO-based small-area cells, these preliminary results have clearly shown great possibility for the space application of these emerging solar cell technologies.

With the rapid development of non-fullerene small molecule acceptors [10,11] and flexible transparent electrodes [12], flexible organic solar cells (FOSCs) have reached high performances of 17.5% [13] and 16.71% [14] for 0.062 and 1 cm2 cells, respectively, which are close to that of the corresponding rigid ITO-glass based cells [15]. More importantly, ultrathin OSCs with a total thickness of a few micrometers can be achieved using plastic substrates like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [16], polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [5], polyethylenaphthalate (PEN) [17], polyimide (PI) [18,19] and perylene [20]. With these, the highest power-per-weight, over 33 kW/kg, was reported [6], pushing the OSCs forward to near-space applications. For use in space, the devices will suffer from extreme environments, including large temperature contrast, high vacuum, strong ultraviolet radiation, and various solar cosmic rays [21]. Regarding these, some terrestrial simulated experiments have been carried out. For example, Lee et al. found polymer:fullerene OSCs have good durability under five complete thermal cycles between −100 and 80°C [22]. Meanwhile, Troshin et al. demonstrated impressive radiation resistibility of the PCDTBT : PC61BM OSCs, with ∼90% of efficiency remaining when exposed to radiation at a dose of 6500 Gy, which was equivalent to 10 years of space radiation dose [23]. For stratospheric usage, the FOSCs module was tested in near-space in the frame of Optical Sensors based on CARbon materials mission (OSCAS) [7], however, the performance of the FOSC module was around 1.6%, which is much lower than the state-of-the-art PCE of the FOSCs. No further research work on the in-situ performance and stability test of the FOSCs in the stratosphere environment was reported.

In this work, we explored the in situ performance and stability of large-area FOSCs in the 35-km stratosphere environment through a high-altitude balloon. Before the in situ performance measurement, systematical simulation experiments proved the reliability of FOSCs under alternated temperature change and intensive UV irradiation. The in situ measurement results showed that FOSCs gave the highest power density of 15.26 mW/cm2 and efficiency of 11.16% at 35 km, which are the record power and performance of OSCs in the space environment. In addition, the FOSCs kept stable over 3-h continuous flying at 35 km. These results are of great significance for space solar cells and show a great possibility of large-area FOSCs for space usage.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

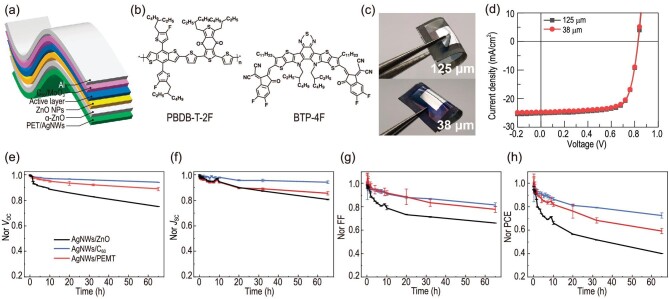

Performance and stability tests of the FOSCs in the lab

FOSCs with an inverted structure of AgNWs/α-ZnO/ZnO NPs/PBDB-T-2F : BTP-4F/C60/MoO3/Al [24] with an area of 0.64 cm2 were fabricated using 125 or 38 μm PET as substrates (Fig. 1a). Figure 1b and c show the molecular structures of PBDB-T-2F and BTP-4F, and the photographs of the devices. The J−V characteristics and performance parameters of these devices are shown in Fig. 1d and Table S1. A highest efficiency of 14.61% and 15.01% was achieved for the 125- and 38-μm–thick PET substrate-based devices. These device performances were comparable to the small-area FOSCs we have reported previously [24,25], and among the highest performance of the large-area FOSCs with a PBDB-T-2F : BTP-4F photoactive layer [26–29]. This result indicated the suitability of AgNWs electrode for large-area high-performance ultrathin FOSCs. In addition, the FOSCs on 38-μm–thick substrates (Fig. S1) yielded an extremely high power-per-weight of 3.32 kW/kg, making this type of solar cell ideal for use in space.

Figure 1.

(a) Device structure, (b) the molecular structures of PBDB-T-2F and BTP-4F, (c) photographs and (d) the J−V characteristics of the FOSCs. (e–h) Evolution of the performance during irradiation under 365-nm UV illumination for 60 h.

In this work, ZnO nanoparticle (NP) was chosen as the electron transporting layer (ETL) because of its high working thickness, which could ensure total coverage of the relatively rough AgNWs by ETLs and high performance of the devices. While other polymer ETLs, i.e. PEI-, PFN-Br–, and PDINO ETL-based devices showed short-circuit or inferior device performance due to their poor coverage on the AgNWs electrode (as shown in Fig. S2). In terms of space application, the FOSCs have to withstand strong UV irradiation; we know the typical photocatalyst effect of ZnO would accelerate performance degradation during long-term illumination, specifically in the case of UV irradiation [26,30]. To solve this problem, we modified the ZnO ETLs with C60 and 2-phenylethylmercaptan (PEMT). Figure 1e–h shows the evolution of the performance parameter during 60-h irradiation under 365-nm UV illumination. We found all the devices showed a gradual decline of VOC, JSC, and FF under UV light illumination. The decreased VOC and FF would be ascribed to the change in the work function of ZnO. It was found the surface potential of ZnO (Figs S3 and S4) increased by 0.24 eV during UV irradiation. The decrease in JSC was due to the decomposition of the non-fullerene acceptor because of the photocatalyst effect of ZnO, which could be evidenced by the UV-vis absorbance spectra (Fig. S5). Compared with the pristine ZnO ETL, the devices with ZnO/C60 or ZnO/PEMT ETL declined at a much slower rate, fully proving that the insertion of the C60 derivative [10,31] or PEMT [28,30] between ZnO and the organic photoactive layer is effective in restraining the interface degradation under UV irradiation. Compared with ZnO/PEMT, the insertion of C60 might form a more compact barrier layer between ZnO and the organic layer, thereby leading to the slowest degradation speed. In detail, 80% of the initial efficiency remained after 60-h illumination, while only 40% of the initial efficiency remained for the pristine device (Fig. 1h). Based on these results, ZnO/C60 ETL was utilized as the ETL in the following work.

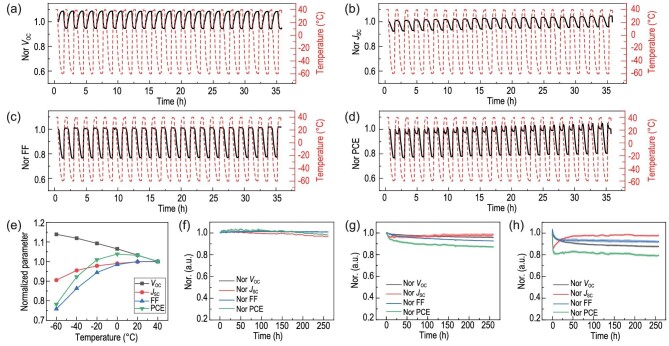

We know the space environment will have large temperature variations and rapid temperature changes, which would lead to the formation of cracks or delamination due to repeated material expansion and compression. Thus, the performance change under rapid thermal cycles is vital. According to the in situ temperature data, we found the real temperature at 35-km high altitude in daylight typically changes from −40 to 40°C (vide infra), which has also been reported in previous works [7,8]. Therefore, we evaluated the performance and durability of the FOSCs during thermal cycles with temperatures varying from 40 to −60°C (Fig. 2a–d). In detail, the devices were stored in the LED light source integrated climate chamber (Fig. S6), and J−V curves were periodically recorded under continuous illumination. As shown in Fig. 2, we found VOC at −60oC was higher than that at 40oC, while devices JSC and FF were lower at low temperatures. As a consequence, device efficiency at −60°C was around 80% of the efficiency of that at 40°C. Similar thermal cycle results of OSCs have been reported previously [22]. The higher VOC at −60oC relative to 40oC would be ascribed to less material disorder [32], and lower JSC and FF at −60°C might be due to relatively low carrier transporting [22]. Though the FOSCs showed inferior performance at low temperatures, the device remained stable during 40 thermal cycles, implying the devices could sustain good interface contact without serious cracks or delamination although material expansion or shrinkage would occur during the thermal cycle process. More importantly, it is noteworthy that the real temperature generally alters from 0 to 40oC when the devices are directly irradiated by sunlight [7,8]. Therefore, this durability during fluctuating temperature changes should be more important than the performance at low temperature in terms of near-space usage.

Figure 2.

Evolution of (a) VOC, (b) JSC, (c) FF and (d) PCE during the thermal cycle. (e) Temperature-dependent device performance (normalized with values of 40oC). Evolution of the device performance under continuous illumination at (f) −60°C, (g) 25°C and (h) 85°C.

To better understand the temperature effect, we systematically investigated the device performance of the FOSCs at different temperatures. As shown in Fig. S7, VOC gradually decreased as temperature increased from −60 to 40oC, while JSC and FF slightly increased. The changing trend of VOC could be described by variation of trap states, which could be described by the following equation [32]:

|

(1) |

where q is the elementary charge, Eg is the energy gap,  n

n p) is the width of Gaussian density-of-state of acceptor and donor, Nn(Np) is the effective states density of electron and hole, and n(p) is the free electron (hole) concentration. For the amorphous material-based device, VOC was generally dependent on the value of

p) is the width of Gaussian density-of-state of acceptor and donor, Nn(Np) is the effective states density of electron and hole, and n(p) is the free electron (hole) concentration. For the amorphous material-based device, VOC was generally dependent on the value of  . As temperature decreased, there would be more disordered tail states, resulting in larger

. As temperature decreased, there would be more disordered tail states, resulting in larger  , thereby VOC decreased as the temperature rose. The decrease of JSC and FF with the drop in temperature was observed, which might come from increased series resistance since the carrier mobility of the organic semiconductor materials would be lower as the temperature decreases. As a consequence, PCE increased with temperature increasing from −60 to 0oC and then decreased, with 0oC as a saturation. The temperature-dependent VOC, JSC, FF and PCE (Fig. 2e) clearly showed the relationship between the environmental temperature and device performance.

, thereby VOC decreased as the temperature rose. The decrease of JSC and FF with the drop in temperature was observed, which might come from increased series resistance since the carrier mobility of the organic semiconductor materials would be lower as the temperature decreases. As a consequence, PCE increased with temperature increasing from −60 to 0oC and then decreased, with 0oC as a saturation. The temperature-dependent VOC, JSC, FF and PCE (Fig. 2e) clearly showed the relationship between the environmental temperature and device performance.

Light intensity-dependent VOC and JSC of the devices at 40, 0 and −60oC were then investigated (Figs S8 and S9) to understand the underlying reason for temperature-dependent performance. The increased slope of VOCvs. light intensity indicated that trap-assisted recombination became more dominant in the FOSCs at −60oC than at 0 and 40oC, which was similar to the results for the previous report [33]. Additionally, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) (Fig. S10, Table S2) showed larger recombination resistance at low temperatures. Based on the results of EIS and light-intensity VOC, we speculated large transfer resistance at −60oC from trap-assisted recombination was the main reason for low performance at low temperatures.

Similar temperature-dependent performance has been observed in silicon [34], CIGS [34] and perovskite solar cells [35], which has been ascribed to temperature-dependent carrier dynamics and bandgap change [36]. Recently, Tsoi et al. demonstrated that non-fullerene–acceptor-based OSCs have relatively lower performance at low temperatures (−100 to −20oC) than that at 0oC under the AM0 irradiation condition [33]. In addition, the result was highly dependent on the organic materials used [33], indicating material selection is critical for promoting low-temperature performance for future work.

The long-term stability of the flexible PBDB-T-2F : BTP-4F solar cells at different temperatures (−60°C, 25°C and 85°C) was investigated (Fig. 2f–h). As seen in this figure, we found both VOC and FF were stable under continuous illumination at −60°C, whereas JSC showed around 10% degradation, consequently leading to a 10% decline of efficiency after 300 h aging at −60°C. The slight degradation of JSC might be attributed to the photochemical reaction between the metal oxide and the active layer during continuous illumination, which has been reported in our previous work [26]. In the case of 25oC, we found the device performance also declined by 10% under continuous illumination. At 85°C, the device showed a quick burn-in degradation process within 1 h followed by a long-time stable process. In addition, the recovery phenomenon of JSC was observed during 85oC aging, which might be attributed to the morphology change of the organic photoactive layer [37]. Consequently, the device kept 80% of the initial performance after continuous illumination at 85°C for 300 h. These observations strongly demonstrated that FOSCs have reasonable long-term stability and continuous illumination at different temperatures, suggesting the excellent reliability of FOSCs during thermal cycling under near-space conditions [38]. Under comprehensive consideration of thermal cycle properties and UV resistance, the device structure of AgNWs/α-ZnO/ZnONP/C60/PBDB-T-2F:BTP-4F/C60/MoO3/Al was chosen for further in situ near-space measurement.

In situ performance and stability test of FOSCs in stratospheric environment

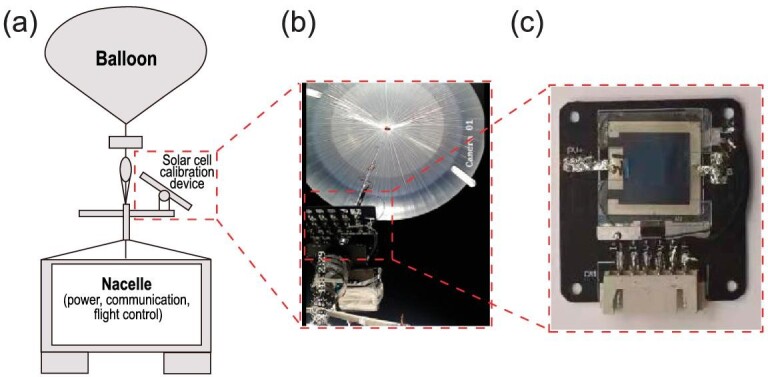

To evaluate the device performance of FOSCs in a stratosphere environment, six PBDB-T-2F : BTP-4F FOSCs devices were launched at 35-km high altitude through a high-altitude balloon. Before flying, both sides of the FOSCs were encapsulated by water and oxygen barrier films, which resulted in a slight decrease in performance due to optical loss (Table S3).

Figure 3a exhibits the schematic diagram of the high-altitude balloon measurement system. In detail, it consists of a high-altitude balloon, a cutter, a parachute, a measurement instrument, a pod, a control antenna, a buffered device and a cable. The high-altitude balloon is used to provide buoyancy to support the flight, the pod is used to store the electrical and communication units, and the cutter is used to stop the balloon flight at the end of the mission, or in an unexpected situation.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic diagram of the measurement instrument. (b) Photograph of the balloon for test at 35 km. (c) Photograph of the devices for test.

The cable is connected between the parachute and the pod, and consists of single or multiple rope belts (Fig. 3b). The high-altitude solar cell measurement is mainly composed of a support plate, a calibration plate, an azimuth stepper motor, a pitch stepper motor, a signal acquisition box, a solar tracking controller, a conductive slip ring and a cabin connector. The high-altitude in situ calibration instrument is clamped at the bottom of the connecting cable and begins to work after the balloon lifts off and reaches a certain flight height. The flight process is controlled by the sun tracking controller, which will track the position of the sun. The J−V testing system will collect the testing data and transmit them to the ground through the balloon communication link. In detail, each cell is separately connected with a separate I−V scan and signal sampling circuit to achieve an I−V curve within 1 s, and then the obtained I−V data are saved in the SD card and directly transmitted to the ground control room. Before the flight experiments, the solar cells were fixed on the circuit board (as shown in Fig. 3c). Here it is worth noting that although the balloon was continuously rotating in the sky due to wind, the use of a sun trajectory tracking system and photoelectronic tracking system could quickly calculate the accurate location and guide the balloon to quickly regulate its relative angle as long as the wind is not too strong. In this tracking system, a compass was used to detect the orientation and angle of the measurement instrument (as shown in Fig. S11), which would then guide the measurement instrument to locate the sun. On the other side, the incidence angle of the sun could be determined using the photoelectronic tracking system, which could correspondingly regulate the location to ensure that samples have been vertically illuminated.

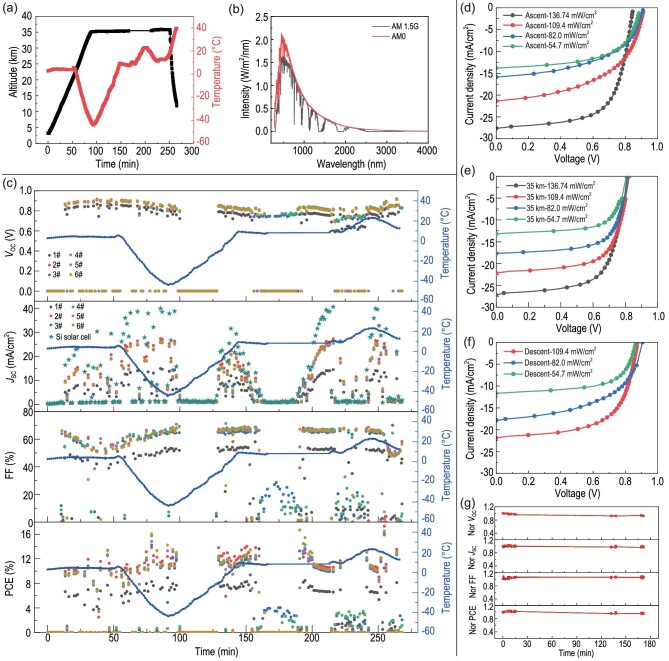

Balloon altitude and environmental temperature were recorded by GPS and temperature sensors, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4a, the balloon rose to 35 km from 7 : 35 AM to 8 : 50 AM on 26 September 2021, and kept at 35-km altitude until 11 : 35 AM, and finally landed within 10 min. Regarding the temperature, we found it varied from 10°C to −40°C during the ascent step, varied from −8°C to 50°C during the level flight step, and then quickly decreased from 40°C to −40°C within 10 min, and finally rose to 10°C during the descent step. Solar irradiation intensity was estimated according to the current of the standard silicon solar cells. Figure 4b shows the solar spectrum of AM 1.5G and AM0. Overall, we found the AM0 solar spectrum contains much stronger UV irradiation than AM 1.5G spectrum. The standard irradiation intensity of AM 1.5G and AM0 is 100 and 136.7 mW/cm2, respectively. During the flight, the evolution of VOC, JSC, FF and PCE of the devices during temperature change was recorded and exhibited in Fig. 4c. However, we should point out that it is difficult to accurately analyse the impact of temperature on the device performance since the irradiation intensity changed due to the variation of incidence angle of sunlight, and the orientation and angle of the instrument. During the first 10 min, since the devices were far away from the sun at this step, both VOC and JSC were nearly 0. During the flying step from 10 to 100 min, the FOSCs gave a VOC of about 0.80 V. During the level flying step, the devices showed a similar VOC of 0.80 V. Regarding JSC, we found it gradually increased during the rising step, and varied largely from around 5.0 to 28.0 mA/cm2 during the whole process. Such a large variation of JSC was caused by location changes during flight. FF was relatively stable during the whole process. In all, it was inspiring to find that the device showed an average performance of 11.0% to ∼13.0%, with the highest efficiency approaching 15%. Figure 4d–f shows the typical J−V characteristics of the devices at the ascent, level flying, and descent steps with different irradiation intensities, and the corresponding performance parameters are listed in Table S4. In addition, the dependence of JSC on incidence angle was investigated and exhibited in Fig. S12. We found the incidence angle changed from 4o to 20o during the flight, and correspondingly the JSC of the FOSCs varied from 26.5 to 28.0 mA/cm2. Additionally, increased JSC was observed when the incidence angle was smaller, and the maximum JSC was achieved with an angle of 4o.

Figure 4.

(a) Flying height and environment temperature. (b) The solar spectrum of AM0 and AM 1.5G. (c) Evolution of VOC, JSC, FF and PCE during the flight. (d–f) J−V curves of the FOSCs at different flying steps. (g) Device performance during 3 h of flight at 35 km.

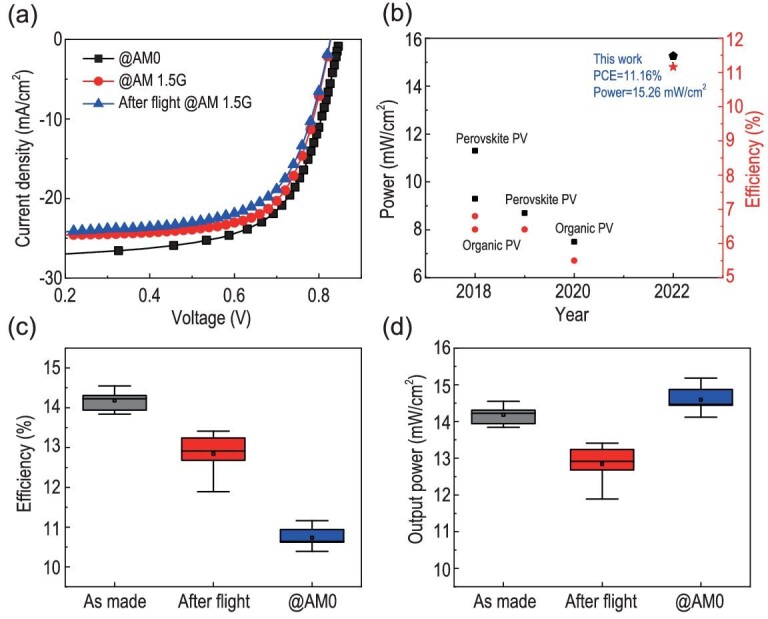

The performance evolution of the FOSCs during the 3-h flight at 35 km was also investigated and is shown in Fig. 4g. All the parameters, including VOC, JSC, FF and PCE presented a negligible decline, suggesting the FOSCs would be long-term stable in the stratospheric environment. The typical device performances of the six individual devices are listed in Table 1. We found these flexible devices showed similar performance, and the top device gave a VOC, JSC, FF and PCE of about 0.85 V, 26 mA/cm2, 65% and 11.16%, respectively. To evaluate the application potential of FOSCs in near-space, the device output power at AM0 and AM 1.5G was calculated and listed in Table 1. The typical J−V characteristics of FOSCs at AM0 and AM 1.5G are shown in Fig. 5a. As listed in Table 1, the FOSCs gave a higher output power under AM0 illumination than under AM 1.5G illumination. A highest power of 15.26 and 14.70 mW/cm2 was observed at AM0 and AM1.5G illumination, respectively. Such a high power and efficiency of FOSCs was the highest performance of OSCs in the stratospheric environment as far as we know [7,9], which was even higher than that of the perovskite solar cells (Table S5).

Table 1.

Device performance of FOSCs at 35 km and in the lab.

| Entry | V OC (V) | J SC (mA/cm2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) @AM0a | Power@AM0 (mW/cm2) | Power@AM1.5G (mW/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.846 | 27.63 | 65.29 | 11.16 | 15.26 | 14.36 |

| 2 | 0.843 | 26.25 | 64.14 | 10.39 | 14.20 | 14.70 |

| 3 | 0.851 | 26.11 | 65.47 | 10.64 | 14.55 | 14.34 |

| 4 | 0.848 | 26.31 | 65.04 | 10.63 | 14.52 | 14.64 |

| 5 | 0.848 | 26.23 | 65.22 | 10.64 | 14.55 | 13.41 |

| 6 | 0.845 | 26.94 | 65.72 | 10.93 | 14.95 | 14.27 |

AM0 spectrum: illumination intensity is 136.7 mW/cm2.

Figure 5.

(a) J−V characteristics of the FOSCs in the terrestrial and near-space environments. (b) Summary of power and device efficiency of FOSCs in the stratospheric environment that have been reported [7–9]. (c) Device performance and (d) output power of the six individual FOSCs.

Reliability checks of FOSCs after high-altitude test

After in situ performance measurement, we collected the devices and measured the performance under the illumination of AM 1.5G spectrum, and the performance is listed in Table S3. The performance and output power before and after flying and the performance in the terrestrial and near-space environments are shown in Fig. 5c and d. As shown in Fig. 5c, less than a 10% efficiency decline was observed after the stratospheric flight. Additionally, we found the degradation trend of these space-measured devices was similar to the control device (entry 7 in Table S3), suggesting natural degradation due to an inadequate water and oxygen barrier of encapsulation as the main reason for performance degradation. In other words, the FOSCs would be stable under near-space conditions if encapsulation is reliable. Based on the device performance of the fresh devices and the re-checked performance, we know the FOSCs could resist the extreme environment of near-space and keep stable.

CONCLUSION

To evaluate the application potential of ultra-flexible OSCs in near space, both simulated experiments and in situ measurements at 35-km high altitude were investigated. The use of ZnO/C60 ETL was beneficial for enhancing UV durability. The terrestrial simulated experiments demonstrated that FOCSs with an inverted structure could withstand thermal cycles and UV irradiation. The flexible large-area OSCs gave an efficiency of higher than 11.0% and an outpower of higher than 15.0 mW/cm2 in the 35-km near-space environment, which corresponded to a power per weight of 3.32 kW/kg. In addition, the FOSCs kept stable during 3 h of flying at 35 km with only slight performance degradation. This work provided strong evidence of the application potential of large-area FOSCs with high performance and high power per weight as aerospace photovoltaics.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Zihan Xu, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China; School of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Guoning Xu, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Qun Luo, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China; School of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Yunfei Han, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China.

Yu Tang, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China.

Ying Miao, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China.

Yongxiang Li, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China.

Jian Qin, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China.

Jingbo Guo, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China.

Wusong Zha, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China.

Chao Gong, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China.

Kun Lu, CAS Key Laboratory of Nanosystem and Hierarchical Fabrication, National Center for Nanoscience and Technology, Beijing 100190, China.

Jianqi Zhang, CAS Key Laboratory of Nanosystem and Hierarchical Fabrication, National Center for Nanoscience and Technology, Beijing 100190, China.

Zhixiang Wei, CAS Key Laboratory of Nanosystem and Hierarchical Fabrication, National Center for Nanoscience and Technology, Beijing 100190, China.

Rong Cai, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China.

Yanchu Yang, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China.

Zhaojie Li, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China.

Chang-Qi Ma, i-Lab & Printable Electronic Center, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, China; School of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22135001 and 22075315), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (2019317), and the Scientific Experimental System in Near Space of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA17020304).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Q. Luo, G.N. Xu and C.-Q. Ma initiated and organized this project. Z.H. Xu fabricated the FOSCs, and measured the performance of devices under AM 1.5G irradiation, during the thermal cycle and under UV irradiation. Y.F. Han, J.Q. Zhang and K. Lu fabricated the flexible OSCs. J. Qin and J.B. Guo encapsulated the devices and welded the device to the printed circuit board. G.N. Xu, Q. Luo, Y. Tang, Y.X. Li, R. Cai, Y.C. Yang and Z.J. Li carried out the high-altitude flight experiment. Z.H. Xu and Q. Luo wrote the initial draft. G.N. Xu. Z.X. Wei and C.-Q. Ma revised the manuscript. The manuscript was written with contributions from all the authors.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stolle C, Floberghagen R, Lühr Het al. . Space weather opportunities from the Swarm mission including near real time applications. Earth Planet Sp 2013; 65: 1375–83. 10.5047/eps.2013.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li Y, Zhong S, Zhuang Yet al. . Quasi-omnidirectional ultrathin silicon solar cells realized by industrially compatible processes. Adv Electron Mater 2019; 5: 1800858. 10.1002/aelm.201800858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Han J, Abbott MD, Hamer PGet al. . Ultrathin silicon solar cell loss analysis. IEEE J Photovolt 2016; 6: 1160–6. 10.1109/JPHOTOV.2016.2590949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nassiri Nazif K, Daus A, Hong Jet al. . High-specific-power flexible transition metal dichalcogenide solar cells. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 7034. 10.1038/s41467-021-27195-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cui N, Song Y, Tan CHet al. . Stretchable transparent electrodes for conformable wearable organic photovoltaic devices. npj Flex Electron 2021; 5: 31. 10.1038/s41528-021-00127-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiong S, Fukuda K, Lee Set al. . Ultrathin and efficient organic photovoltaics with enhanced air stability by suppression of zinc element diffusion. Adv Sci 2022; 9: e2105288. 10.1002/advs.202105288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cardinaletti I, Vangerven T, Nagels Set al. . Organic and perovskite solar cells for space applications. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 2018; 182: 121–7. 10.1016/j.solmat.2018.03.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tu Y, Xu G, Yang Xet al. . Mixed-cation perovskite solar cells in space. Sci China Phys Mech Astron 2019; 62974221. 10.1007/s11433-019-9356-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reb LK, Böhmer M, Predeschly Bet al. . Perovskite and organic solar cells on a rocket flight. Joule 2020; 4: 1880–92. 10.1016/j.joule.2020.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li C, Zhou J, Song Jet al. . Non-fullerene acceptors with branched side chains and improved molecular packing to exceed 18% efficiency in organic solar cells. Nat Energy 2021; 6: 605–13. 10.1038/s41560-021-00820-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cui Y, Yao H, Zhang Jet al. . Single-junction organic photovoltaic cells with approaching 18% efficiency. Adv Mater 2020; 32: 1908205. 10.1002/adma.201908205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han Y, Hu Z, Zha Wet al. . 12.42% monolithic 25.42 cm2 flexible organic solar cells enabled by an amorphous ITO-modified metal grid electrode. Adv Mater 2022; 34: 2110276. 10.1002/adma.202110276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zeng G, Chen W, Chen Xet al. . Realizing 17.5% efficiency flexible organic solar cells via atomic-level chemical welding of silver nanowire electrodes. J Am Chem Soc 2022; 144: 8658–68. 10.1021/jacs.2c01503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu X, Zheng Z, Wang Jet al. . Fluidic manipulating of printable zinc oxide for flexible organic solar cells. Adv Mater 2022; 34: 2106453. 10.1002/adma.202106453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu L, Zhang M, Xu Jet al. . Single-junction organic solar cells with over 19% efficiency enabled by a refined double-fibril network morphology. Nat Mater 2022; 21: 656–63. 10.1038/s41563-022-01244-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaltenbrunner M, White MS, Glowacki EDet al. . Ultrathin and lightweight organic solar cells with high flexibility. Nat Commun 2012; 3: 770. 10.1038/ncomms1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang JX, Han CY, Bi FZet al. . Overlapping fasten packing enables efficient dual-donor ternary organic solar cells with super stretchability. Energy Environ Sci 2021; 14: 5968–78. 10.1039/D1EE02320A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu X, Fukuda K, Karki Aet al. . Thermally stable, highly efficient, ultraflexible organic photovoltaics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115: 4589–94. 10.1073/pnas.1801187115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koo D, Jung S, Seo Jet al. . Flexible organic solar cells over 15% efficiency with polyimide-integrated graphene electrodes. Joule 2020; 4: 1021–34. 10.1016/j.joule.2020.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jinno H, Yokota T, Koizumi Met al. . Self-powered ultraflexible photonic skin for continuous bio-signal detection via air-operation-stable polymer light-emitting diodes. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 2234. 10.1038/s41467-021-22558-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tu Y, Wu J, Xu Get al. . Perovskite solar cells for space applications: progress and challenges. Adv Mater 2021; 33: e2006545. 10.1002/adma.202006545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee HKH, Durrant JR, Li Zet al. . Stability study of thermal cycling on organic solar cells. J Mater Res 2018; 33: 1902–8. 10.1557/jmr.2018.167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martynov IV, Akkuratov AV, Luchkin SYet al. . Impressive radiation stability of organic solar cells based on fullerene derivatives and carbazole-containing conjugated polymers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019; 11: 21741–8. 10.1021/acsami.9b01729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pan W, Han Y, Wang Zet al. . An efficiency of 14.29% and 13.08% for 1 cm2 and 4 cm2 flexible organic solar cells enabled by sol–gel ZnO and ZnO nanoparticle bilayer electron transporting layers. J Mater Chem A 2021; 9: 16889–97. 10.1039/D1TA03308E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Z, Han Y, Yan Let al. . High power conversion efficiency of 13.61% for 1 cm2 flexible polymer solar cells based on patternable and mass-producible gravure-printed silver nanowire electrodes. Adv Funct Mater 2021; 31: 2007276. 10.1002/adfm.202007276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu BW, Han YF, Li ZRet al. . Visible light-induced degradation of inverted polymer:nonfullerene acceptor solar cells: initiated by the light absorption of ZnO layer. Sol RRL 2021; 5: 2000638. 10.1002/solr.202000638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhao H, Lin B, Xue Jet al. . Kinetics manipulation enables high-performance thick ternary organic solar cells via R2R-compatible slot-die coating. Adv Mater 2022; 34: e2105114. 10.1002/adma.202105114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Han Y, Dong H, Pan Wet al. . An efficiency of 16.46% and a T80 lifetime of over 4000 h for the PM6:Y6 inverted organic solar cells enabled by surface acid treatment of the zinc oxide electron transporting layer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021; 13: 17869–81. 10.1021/acsami.1c02613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zheng X, Zuo L, Zhao Fet al. . High-efficiency ITO-free organic photovoltaics with superior flexibility and up-scalability. Adv Mater 2022; 34: 2200044. 10.1002/adma.202200044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu B, Su X, Lin Yet al. . Simultaneously achieving highly efficient and stable polymer:non-fullerene solar cells enabled by molecular structure optimization and surface passivation. Adv Sci 2022; 9: e2104588. 10.1002/advs.202104588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu X, Xiao J, Zhang Get al. . Interface-enhanced organic solar cells with extrapolated T80 lifetimes of over 20 years. Sci Bull 2020; 65: 208–16. 10.1016/j.scib.2019.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nayak PK, Garcia-Belmonte G, Kahn Aet al. . Photovoltaic efficiency limits and material disorder. Energy Environ Sci 2012; 5: 6022–39. 10.1039/c2ee03178g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ram D, Harrison Ka Hin L, Guihuan Zet al. . Organic solar cell at stratospheric condition for high altitude platform station application. Chin J Chem 2022; 40: 2927–32. 10.1002/cjoc.202200481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu SH, Simburger EJ, Matsumoto Jet al. . Evaluation of thin-film solar cell temperature coefficients for space applications. Prog Photovolt: Res Appl 2005; 13: 149–56. 10.1002/pip.602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barbe J, Pockett A, Stoichkov Vet al. . In situ investigation of perovskite solar cells' efficiency and stability in a mimic stratospheric environment for high-altitude pseudo-satellites. J Mater Chem C 2020; 8: 1715–21. 10.1039/C9TC04984C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ma ZQ, Du HW, Wang YLet al. . Temperature-dependent photovoltaic performance of a SQIS device. IEEE Phot Spec Conf. 2021; 2407–11. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mateker WR, McGehee MD. Progress in understanding degradation mechanisms and improving stability in organic photovoltaics. Adv Mater 2017; 29: 1603940. 10.1002/adma.201603940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bailey S, Raffaelle R. Handbook of Photovoltaic Science and Engineering: Space solar cells and arrays. Chichester: Wiley, 2010, 365–401. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.