Abstract

The CRISPR-Cas system in Klebsiella pneumoniae can prevent the entry of blaKPC-IncF plasmids. However, some clinical isolates bear the KPC-2 plasmids despite carrying the CRISPR-Cas system. The purpose of this study was to characterize the molecular features of these isolates. A total of 697 clinical K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from 11 hospitals in China, and tested for the presence of CRISPR-Cas systems using polymerase chain reaction. Overall, 164 (23.5%) of 697 K. pneumoniae isolates had type I-E* (15.9%) or type I-E (7.7%) CRISPR-Cas systems. The most prevalent sequence type among isolates carrying type I-E* CRISPR was ST23 (45.9%), followed by ST15 (18.9%). Isolates with CRISPR-Cas system were more susceptible to ten antimicrobials tested, including carbapenems, compared with the CRISPR-negative isolates. However, there were still 21 CRISPR-Cas-carrying isolates that showed resistance to carbapenems, and these isolates were subjected to whole-genome sequencing. Thirteen of these 21 isolates carried blaKPC-2-bearing plasmids, of which nine had a new plasmid type, IncFIIK34, and two had IncFII(PHN7A8) plasmids. In addition, 12 of these 13 isolates belonged to ST15, while only eight (5.6%, 8/143) isolates belonged to ST15 in carbapenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae carrying CRISPR-Cas systems. In conclusion, we found that blaKPC-2-bearing IncFII plasmids could co-exist with the type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems in ST15 K. pneumoniae.

Keywords: carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, KPC-2, plasmid, CRISPR-Cas system, ST15

Introduction

Prokaryotic organisms have developed numerous defense systems to protect themselves against parasitic nucleic acids, such as plasmids and viruses (bacteriophages; Hampton et al., 2020). Among these systems, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) loci and CRISPR-associated (cas) genes dedicated to nucleic acid manipulation (Jansen et al., 2002) encode a unique defense mechanism that provides adaptive immunity against foreign elements. CRISPR loci are widely distributed and have been found in the genomes of about 42% of bacteria and 85% of archaea (Makarova et al., 2020). In these loci, an array of short, partially palindromic, repetitive noncoding DNA sequences is separated by equally short variable sequences known as spacers (Barrangou et al., 2007; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008; Pitout et al., 2015). Currently, CRISPRs are divided into two main classes, which encompass six major types (I–VI) and a total of 50 different subtypes based on their sequences (Makarova et al., 2020).

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important human pathogen both in hospital and community settings. Increasing resistance to carbapenem in K. pneumoniae raises a global public health concern because of the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) and the associated high rate of mortality (Logan and Weinstein, 2017). The sequence types (STs) ST11 and ST258, belonging to clonal complex 258 (CC258), are well-established and compose the largest CRKP clonal group worldwide (Lee et al., 2016). Absence of the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system in K. pneumoniae CC258 was found to be associated with dissemination of IncF epidemic-resistance plasmids (Tang et al., 2020). K. pneumoniae ST15 is an emerging international high-risk clone causing nosocomial outbreaks worldwide (Lee et al., 2016) and the second most prevalent clone among CRKP isolates in China (Wang M. et al., 2022). Therefore, the molecular epidemiology of the CRISPR-Cas system of ST15 K. pneumoniae needs to be further determined.

In China, the dominant carbapenemase produced by CRKP is KPC-2, accounting for up to 94% (Wang M. et al., 2022). KPC-2 is generally located in the incompatibility group F (IncF) plasmids (Peirano et al., 2017). CRISPR-Cas systems identified in K. pneumoniae are categorized into type I-E and subtype I-E* (Shen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). Previous studies have shown that the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system of K. pneumoniae can prevent the acquisition of the blaKPC-IncF plasmid (Zhou et al., 2020), and the type I-E* CRISPR-Cas system of a K. pneumoniae isolate (NTUH-K2044) contributes to decrease of plasmid transformation and stability (Lin et al., 2016).

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates

A total of 697 consecutive, non-duplicate clinical K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from 11 hospitals in eight provinces in China between July 2018 and January 2019 (Supplementary Table S1). All of the isolates were initially identified as K. pneumoniae using a Vitek II system (bioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. K. pneumoniae was grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or broth at 37°C. The isolates were stored at −80°C in LB broth containing 30% glycerol (v/v) until used.

CRISPR-Cas system identification

DNA was extracted using the boiling method. The collected clinical isolates were tested for the presence of CRISPR-Cas systems (including type I-E* and type I-E CRISPR systems) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers from a previous study (Li et al., 2018). PCRs were prepared using 2 × Hieff™ PCR Master Mix (with dye) (Yeasen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (12.5 μL of Master Mix, 10 μM of each primer, and 1 μL DNA template, with a total volume of 25 μL).

Multi-locus sequence typing

Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on type I-E* and type I-E CRISPR-containing isolates by amplifying seven housekeeping genes, rpoB, gapA, mdh, pgi, phoE, infB, and tonB. STs were assigned by querying the MLST database of K. pneumoniae.1

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All of the clinical isolates were tested for susceptibility to 16 antimicrobial agents, including ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antimicrobial agents were determined using the agar dilution method of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), while the broth dilution method was used for colistin and tigecycline (CLSI, 2019). For colistin, the breakpoints defined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)2 were applied, whereas the breakpoints of tigecycline were interpreted according to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain.

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

A total of 21 CRKP isolates carrying CRISPR-Cas systems were sequenced using a HiSeq X10 Sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States), with 150 bp paired-end short reads and 200X coverage. Of the 21 isolates, 13 isolates were also subjected to long-read sequencing using a MinION Sequencer (Nanopore; Oxford, United Kingdom). Both short and long reads were utilized to generate a de novo hybrid assembly using Unicycler (Wick et al., 2017) and Pilon (Walker et al., 2014). CRISPRCasFinder3 was used to detect CRISPR arrays (repeats and spacers) and cas genes in the genomes. Acquired antimicrobial resistance genes and IS were identified by ResFinder 3.2 and ISfinder (Siguier et al., 2006) using BLAST (Zankari et al., 2012). tra gene cluster was identified by ICEfinder (Liu et al., 2019). Replicon STs of plasmids were determined using the pMLST database.4 Comparisons of the sequences were plotted using BRIG (Alikhan et al., 2011).

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of the presence of CRISPR-Cas systems between the susceptible and resistant isolates. Chi-square tests were used to test the difference between carbapenem-susceptibility and CRISPR-Cas systems. Statistical significance was assessed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Prism) software. p-values of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Prevalence of CRISPR-Cas systems in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae

Overall, 23.5% (164/697) of clinical K. pneumoniae isolates had CRISPR-Cas systems, and type I-E* was more common (15.9%, 111/697) than type I-E (7.7%, 54/697). One isolate had both type I-E* and type I-E systems, which has not been reported previously in K. pneumoniae.

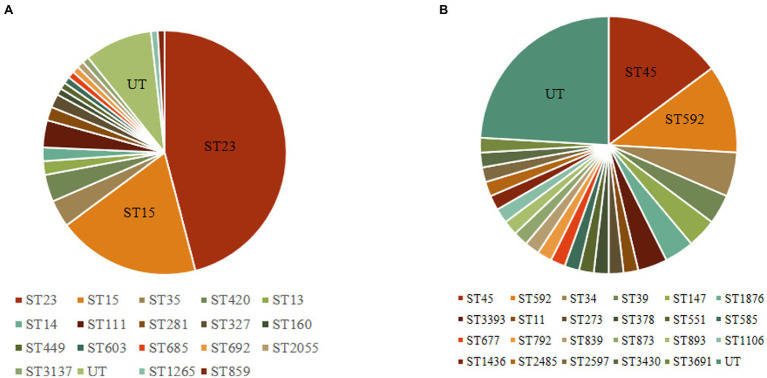

The 164 CRISPR-positive isolates comprised 41 different MLST types (23 isolates were untypable). Type I-E* CRISPR-Cas was found in 18 STs, while type I-E CRISPR-Cas was present in 23 STs (Figure 1). The most prevalent ST among the isolates carrying type I-E* CRISPR was ST23 (n = 51, 45.9%), followed by ST15 (n = 21, 18.9%). The most common ST among type I-E isolates was ST45 (14.8%), and the second was ST592 (11.1%). These results suggested that the distribution of CRISPR-Cas types was associated with particular STs among clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae. Among the 164 CRISPR-positive isolates, only one isolate (BJKP38) was ST11, indicating that CRISPR-Cas loci are rare in ST11 K. pneumoniae.

Figure 1.

Multi-locus sequence typing of 164 clinical isolates carrying CRISPR-Cas systems. (A) Type I-E* CRISPR systems (n = 111). (B) Type I-E CRISPR systems (n = 54). UT, untypable.

Presence of type I-E* and type I-E CRISPR-Cas systems had a negative correlation with antimicrobial resistance

The CRISPR-positive isolates (harboring either the type I-E* or the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system) were significantly more susceptible to 10 antimicrobials tested, including amikacin, aztreonam, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, ertapenem, fosfomycin, imipenem, and meropenem, compared with the CRISPR-negative isolates (Table 1). The rate of carbapenem-resistance of 697 K. pneumoniae was 37.1% (259/697), and the rates of carbapenem-resistance of CRISPR-positive and -negative isolates were 12.8% (21/164) and 44.7% (238/533), respectively (Table 2). Of the 21 CRKP isolates, 17 carried type I-E* and four carried type I-E CRISPR-Cas systems.

Table 1.

The association of antimicrobial susceptibilities with CRISPR-Cas systems in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

| CRISPR-Cas system [Number of susceptible isolates (%)] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I-E* (n = 111) | Type I-E (n = 54) | Absent (n = 533) | p-value | ||

| Amikacin | 98 (88.3) | 49 (90.7) | 346 (64.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Aztreonam | 72 (64.9) | 39 (72.2) | 208 (39.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Cefotaxime | 65 (58.6) | 35 (64.8) | 171 (32.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Cefoxitin | 83 (74.8) | 35 (64.8) | 232 (43.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Ceftazidime | 74 (66.7) | 38 (70.4) | 214 (40.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | 110 (99.1) | 53 (98.1) | 508 (95.3) | 0.067 | 0.499 |

| Chloramphenicol | 71 (64.0) | 29 (53.7) | 218 (40.9) | <0.001 | 0.082 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 66 (59.5) | 28 (51.9) | 158 (29.6) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Colistin | 109 (98.2) | 54 (100.0) | 506 (94.9) | 0.205 | 0.161 |

| Ertapenem | 96 (86.5) | 47 (87.0) | 278 (52.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fosfomycin | 80 (72.1) | 34 (63.0) | 248 (46.5) | <0.001 | 0.021 |

| Imipenem | 100 (90.1) | 48 (88.9) | 296 (55.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Meropenem | 98 (88.3) | 50 (92.6) | 305 (57.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Minocycline | 35 (31.5) | 16 (29.6) | 152 (28.5) | 0.525 | 0.863 |

| Tigecycline | 95 (85.6) | 45 (83.3) | 432 (81.1) | 0.282 | 0.855 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 49 (44.1) | 17 (31.5) | 147 (27.6) | 0.001 | 0.543 |

p-values are shown as CRISPR-negative isolates compared with type I-E* isolates and CRISPR-negative isolates compared with type I-E isolates. The bold p-values were statistically significant.

Table 2.

The association of carbapenem-susceptibilities with CRISPR-Cas systems in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

| CRISPR-Cas (+) n (%) | CRISPR-Cas (−) n (%) | Total | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRKP | 21 (12.8%) | 238 (44.7%) | 259 (37.1%) | |

| CSKP | 143 (87.2%) | 295 (55.3%) | 438 (62.8%) | |

| Total | 164 (100%) | 533 (100%) | 697 (100%) | <0.001 |

CRKP, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae; CSKP, carbapenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae.

Characteristics of 12 ST15 and one ST23 isolates that carried both type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems and blaKPC-2-bearing plasmids

Although most isolates carrying CRISPR-Cas systems were susceptible to carbapenems (87.2%, 143/164), there were still 21 isolates that showed resistance to carbapenems. These 21 isolates were subjected to whole-genome sequencing and genome analysis. More than half of the isolates (n = 13) harbored the carbapenemase-encoding gene blaKPC-2 and type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems, and they were resistant to all three carbapenems tested. Eight other isolates, including all four isolates carrying type I-E CRISPR-Cas systems, did not produce any carbapenemase, and six of the isolates were resistant to ertapenem only, and the remaining two isolates were also resistant to the three carbapenems tested (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of 21 CRKP clinical isolates carrying CRISPR-Cas systems.

| Isolate | CRISPR type | Carbapenemase | Extended-spectrum β-lactamase | blaKPC-2-carrying plasmid size (Kb) | blaKPC-2-carrying plasmid type | ST | MIC (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETP | IPM | MEM | |||||||

| HSKP5 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 94.1 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 32 | 64 |

| HSKP8 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 94.4 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| HSKP33 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-3, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 120.5 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 64 | 128 |

| HSKP43 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 94.1 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 64 | 128 |

| HSKP86 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 94.1 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 32 | 128 |

| HSKP104 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 94.1 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 32 | 64 |

| HSKP107 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 94.1 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 32 | 64 |

| RJKP14 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | SHV-106, SHV-28 | 108.8 | IncFIIK34 | 15 | >32 | 128 | 64 |

| HSKP39 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | SHV-12, SHV-13, SHV-31, SHV-129 | 114.7 | IncFIIK34 | 23 | >32 | 16 | >128 |

| HSKP1 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | SHV-106, SHV-28 | 142.1 | IncFII(PHN7A8) | 15 | >32 | 128 | 128 |

| RJKP41 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-65, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 164.6 | IncFII(PHN7A8) | 15 | >32 | 128 | 64 |

| GZKP13 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-14, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 56.2 | IncFIA(HI1) | 15 | >32 | 32 | 64 |

| RJKP36 | Type I-E* | KPC-2 | CTX-M-15, SHV-106, SHV-28 | 108.8 | IncR | 15 | 16 | 16 | 8 |

| HSKP69 | Type I-E | – | SHV-26, SHV-78, SHV-98, SHV-145 | – | – | 45 | >32 | 64 | >128 |

| HSKP40 | Type I-E | – | SHV-5, SHV-2, SHV-102 | – | – | UT | >32 | 8 | >128 |

| GSKP2 | Type I-E* | – | CTX-M-14, SHV-33 | – | – | 449 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.06 |

| SCKP43 | Type I-E* | – | CTX-M-55, SHV-106, SHV-28 | – | – | 15 | 16 | 1 | 0.5 |

| ZJKP62 | Type I-E* | – | SHV-75 | – | – | 420 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| HSKP140 | Type I-E | – | CTX-M-3, SHV-110, SHV-191 | – | – | 2,485 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 |

| HSKP155 | Type I-E | – | SHV-27 | – | – | 3,393 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| ZJKP12 | Type I-E* | – | SHV-106, SHV-28 | – | – | 14 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 |

ETP, ertapenem; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; ST, sequence type.

The spacer sequences of CRISPR-Cas systems in these 21 isolates were analyzed and compared the difference between the two groups (13 isolates vs. 8 isolates, Supplementary Table S2). The 13 isolates with blaKPC-2-bearing plasmids mainly carried 18 spacers, of which ten spacers were present in 12 isolates, six in 11 isolates, and two in seven isolates. The eight isolates without KPC-2 contained 166 spacers, and each one existed in one to three isolates.

MLST analysis showed that among the 13 isolates carrying both type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems and blaKPC-2, 12 belonged to ST15 and one was ST23 (Table 3), while only eight (5.6%, 8/143) isolates belonged to ST15 in carbapenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae carrying CRISPR-Cas systems. The 12 ST15 isolates were collected from three hospitals, including Huashan Hospital (n = 8) and Ruijin Hospital (n = 3) in Shanghai, and the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (n = 1). The isolation dates of the 12 isolates were from July 2018 to January 2019.

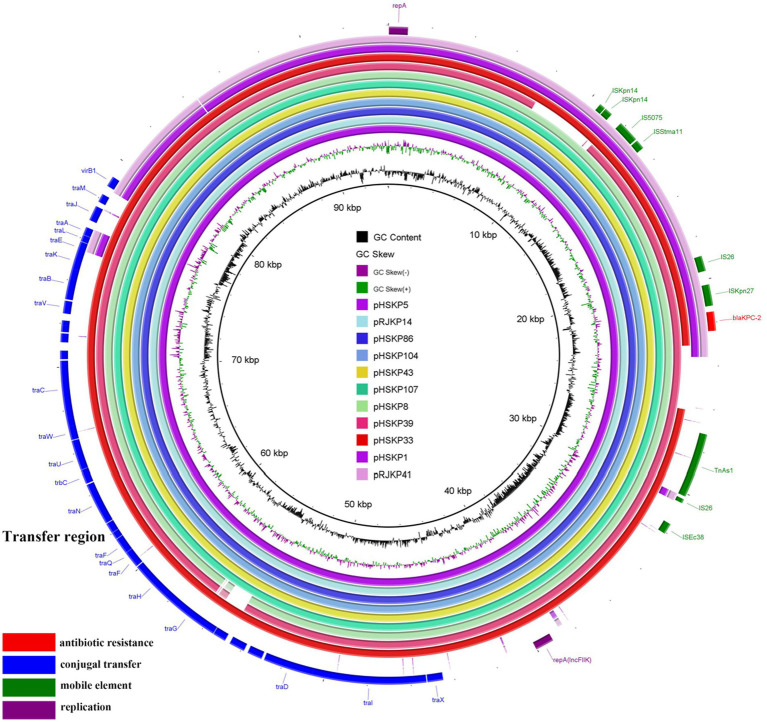

Presence of a new type of IncFIIK34 in nine blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids

The blaKPC-2 genes were located on plasmids in all 13 isolates. Of note, blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids of nine isolates belonged to IncFIIK34 (Table 3), and the sequences of the nine plasmids were highly conserved (Figure 2). The IncFIIK34 replicon was first identified by our group during a study on ST23 CR-HvKP in China and has been submitted to the plasmid MLST database. The IncFIIK34 plasmid was recognized by comparing the sequence of the copA region of the plasmid with the other IncFIIK alleles in the database. All the nine IncFIIK34 plasmids harbored blaKPC-2, meanwhile, pHSKP33 harbored dfrA14 and qnrS1 and pHSKP39 harbored aac(3)-IId, blaSHV-12 and blaTEM-1B additionally. Besides, tra gene cluster that encodes proteins needed for conjugation was identified on all the IncFIIK plasmids, while was absent on IncFII(PHN7A8) plasmids. The blaKPC-2-carrying plasmid types of HSKP1 and RJKP41 were IncFII(PHN7A8), the most common type among ST11 KPC-producing K. pneumoniae, and the plasmid types of the remaining two isolates were IncFIA(HI1) and IncR.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of the nine IncFIIK34 plasmids and two IncFII(PHN7A8) plasmids. The outmost purple and pink circles represent the two IncFII(PHN7A8) plasmids which showed low homology with IncFIIK34.

Among the 13 isolates that carried both type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems and blaKPC-2-bearing plasmids, 11 isolates had self-targeting spacers matching their respective protospacers on blaKPC-2-bearing plasmids, of which two isolates (HSKP1 and RJKP41) had point mutations. The sequence of the self-targeting spacer was 5’-CCGCCGTTT A ATCGCGGTGATGATATCCGGCA-3′ (the point mutation is shown in bold and underlined). The remaining two isolates (GZKP13 and HSKP39) had no spacer matching their blaKPC-2 plasmids. The sequences of hns gene encoding transcriptional repressor H-NS, which showed to prevent the plasmids transformation (Lin et al., 2016), from 13 isolates were identical to that from K. pneumoniae NTUH-K2044. In addition, no mutation of CRISPR-Cas loci was identified on 13 genomes compared to these sequences from CRISPR-Cas finder database.

Discussion

The prevalence of the CRISPR-Cas system in K. pneumoniae was reported to vary from 12.4 to 30.7% (Lin et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Consistently, we found that the CRISPR-Cas system was positive in 164/697 (23.5%) of K. pneumoniae isolates collected from 11 hospitals in China. Previous studies have demonstrated that the scarcity of type I-E CRISPR-Cas systems in the CC258 lineage (including ST11 and ST258) allowed them to readily acquire and adapt to blaKPC-plasmids, and in our study, only one isolate was ST11 among CRISPR-positive K. pneumoniae. It is also notable that ST23, a common ST of the hyper-virulent K. pneumoniae, was the most prevalent ST among type I-E* CRISPR-positive isolates. In this study, one CRISPR-positive ST23 isolate also carried a blaKPC-2-plasmid.

This work showed that nearly all the CRKP isolates carrying both type I-E* CRISPR-Cas system and blaKPC-2-bearing plasmids belonged to ST15. ST15 isolates of K. pneumoniae are emerging international MDR clones, and the molecular features of ST15 are relatively unknown. In this study, ST15 was one of the most prevalent ST carrying type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems. Taken together, it appears that type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems could not prevent the entrance of resistant plasmids into ST15 isolates. Moreover, blaKPC-2-carrying plasmid types of CRKP carrying type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems were mainly the new IncFIIK34, and the sequences of these plasmids are highly conserved.

Most isolates had self-targeting spacers matching their plasmids, only two isolates had point mutations. A previous study demonstrated that single or multiple mutations within the protospacer, but outside a seven-nucleotide seed region immediately following the essential protospacer-adjacent motif, do not lead to the escape of exogenous nucleic acid of viruses (Semenova et al., 2011). It has been reported that anti-CRISPR proteins could inhibit the function of CRISPR-Cas systems (Pawluk et al., 2014), and therefore whether anti-CRISPR proteins existed in these isolates remained to be further studied. In addition, a previous study indicated that CRISPR-Cas immunity is not absolute. It reduces the rate of receipt of the plasmid, but does not prevent its transfer and establishment (Jiang et al., 2013). Hence, further studies are needed to explore the mechanisms by which the IncFIIK34 plasmids evaded type I-E* CRISPR-Cas immunity in K. pneumoniae.

CRISPR-Cas systems are associated with antimicrobial susceptibility in Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and K. pneumoniae (Zheng et al., 2014; van Belkum et al., 2015; Aydin et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). A previous study showed an inverse correlation between the presence of the type I-E* CRISPR-Cas system and antimicrobial resistance, but did not show an association between the distribution of type I-E CRISPR and antimicrobial susceptibilities in K. pneumoniae (Li et al., 2018). Our data showed that the absence of the type I-E* and type I-E CRISPR-Cas systems both contributed to the acquired antimicrobial resistance in K. pneumoniae.

In this study, eight CRKP isolates did not produce any carbapenemases, and six of them were resistant to ertapenem only, but were susceptible to meropenem and imipenem. A previous study of our research group demonstrated that mutations in ramR caused the over-expression of efflux pump and the inhibition of outer membrane protein OmpK35, which was implicated in ertapenem resistance only in K. pneumoniae including the six isolates in this study (Wang D. et al., 2022).

In summary, 23.5% (164/697) of clinical K. pneumoniae isolates had type I-E* or type I-E CRISPR-Cas systems in samples collected in China. Isolates carrying the CRISPR-Cas system were more susceptible to carbapenems, compared with CRISPR-negative isolates. IncFII plasmids could co-exist with the type I-E* CRISPR-Cas systems in ST15 K. pneumoniae, despite the CRISPR-Cas systems contained a spacer matching their own KPC-2 plasmids.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the bioproject PRJNA8534.

Author contributions

MW and QG designed the research and edited the manuscript. YH performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. JJ did the molecular data analysis and wrote the manuscript. DW performed the experiments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81991531).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1125531/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alikhan N. F., Petty N. K., Ben Zakour N. L., Beatson S. A. (2011). BLAST ring image generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genom. 12:402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin S., Personne Y., Newire E., Laverick R., Russell O., Roberts A. P., et al. (2017). Presence of type I-F CRISPR/Cas systems is associated with antimicrobial susceptibility in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 2213–2218. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx137, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Fremaux C., Deveau H., Richards M., Boyaval P., Moineau S., et al. (2007). CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2019). Supplement M100, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 29th edition, Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton H. G., Watson B. N. J., Fineran P. C. (2020). The arms race between bacteria and their phage foes. Nature 577, 327–336. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1894-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R., Embden J. D., Gaastra W., Schouls L. M. (2002). Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Maniv I., Arain F., Wang Y., Levin B. R., Marraffini L. A. (2013). Dealing with the evolutionary downside of CRISPR immunity: bacteria and beneficial plasmids. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003844, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. R., Lee J. H., Park K. S., Kim Y. B., Jeong B. C., Lee S. H. (2016). Global dissemination of Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: epidemiology, genetic context, treatment options, and detection methods. Front. Microbiol. 7:895. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Y., Kao C. Y., Lin W. H., Zheng P. X., Yan J. J., Wang M. C., et al. (2018). Characterization of CRISPR-Cas Systems in Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates uncovers its potential association with antibiotic susceptibility. Front. Microbiol. 9:1595. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01595, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. L., Pan Y. J., Hsieh P. F., Hsu C. R., Wu M. C., Wang J. T. (2016). Imipenem represses CRISPR-Cas interference of DNA acquisition through H-NS stimulation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 6:31644. doi: 10.1038/srep31644, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Li X., Xie Y., Bi D., Sun J., Li J., et al. (2019). ICEberg 2.0: an updated database of bacterial integrative and conjugative elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D660–D665. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1123, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan L. K., Weinstein R. A. (2017). The epidemiology of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. J. Infect. Dis. 215, S28–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw282, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Iranzo J., Shmakov S. A., Alkhnbashi O. S., Brouns S. J. J., et al. (2020). Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 67–83. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J. (2008). CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322, 1843–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.1165771, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawluk A., Bondy-Denomy J., Cheung V. H., Maxwell K. L., Davidson A. R. (2014). A new group of phage anti-CRISPR genes inhibits the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio 5:e00896. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00896-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirano G., Bradford P. A., Kazmierczak K. M., Chen L., Kreiswirth B. N., Pitout J. D. (2017). Importance of clonal complex 258 and IncFK2-like plasmids among a global collection of Klebsiella pneumoniae with blaKPC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02610-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout J. D., Nordmann P., Poirel L. (2015). Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 5873–5884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01019-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova E., Jore M. M., Datsenko K. A., Semenova A., Westra E. R., Wanner B., et al. (2011). Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 10098–10103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104144108, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Lv L., Wang X., Xiu Z., Chen G. (2017). Comparative analysis of CRISPR-Cas systems in Klebsiella genomes. J. Basic Microbiol. 57, 325–336. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201600589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P., Perochon J., Lestrade L., Mahillon J., Chandler M. (2006). ISfinder: the reference Centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Fu P., Zhou Y., Xie Y., Jin J., Wang B., et al. (2020). Absence of the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system in Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal complex 258 is associated with dissemination of IncF epidemic resistance plasmids in this clonal complex. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 890–895. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz538, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belkum A., Soriaga L. B., LaFave M. C., Akella S., Veyrieras J. B., Barbu E. M., et al. (2015). Phylogenetic distribution of CRISPR-Cas Systems in Antibiotic-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio 6, e01796–e01715. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01796-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., et al. (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Earley M., Chen L., Hanson B. M., Yu Y., Liu Z., et al. (2022). Clinical outcomes and bacterial characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae complex among patients from different global regions (CRACKLE-2): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 401–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00399-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Song G., Xu Y. (2020). Association of CRISPR/Cas system with the drug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 1929–1935. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S253380, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Wang M., He T., Li D., Zhang L., Zhang D., et al. (2022). Molecular epidemiology and mechanism of Klebsiella pneumoniae resistance to ertapenem but not to other carbapenems in China. Front. Microbiol. 13:974990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.974990, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017). Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P. X., Chiang-Ni C., Wang S. Y., Tsai P. J., Kuo C. F., Chuang W. J., et al. (2014). Arrangement and number of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat spacers are associated with erythromycin susceptibility in emm12, emm75 and emm92 of group a streptococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 516–523. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12379, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Tang Y., Fu P., Tian D., Yu L., Huang Y., et al. (2020). The type I-E CRISPR-Cas system influences the acquisition of blaKPC-IncF plasmid in Klebsiella pneumonia. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 1011–1022. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1763209, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the bioproject PRJNA8534.