Figure 5.

Reduced PPARA expression in the AEC2 cells from fibrotic lung regions of patients with IPF

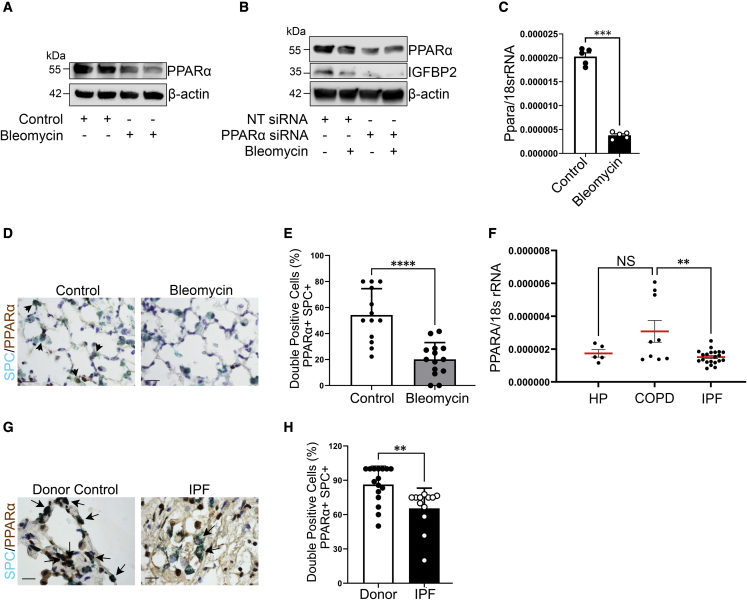

(A) Western blot for the expression of PPARα and β-actin in MLE-12 cells exposed to absence or presence of bleomycin at 4 h.

(B) Non-targeting or Ppara siRNA-transduced MLE-12 cells were exposed to absence or presence of bleomycin treatment at 4 h. Western blot for the expression of PPARα and IGFBP2. β-Actin served as internal control. Data are representative of minimum of 3 independent experiments.

(C) Ppara mRNA expression in the primary AEC2 cells isolated from aged mice subjected to low-dose bleomycin challenge after 14 days. Eukaryotic 18S rRNA was used as an endogenous control (n = 5 WT saline; n = 5 WT bleomycin).

(D) Representative multicolor color immunohistochemistry of lung sections from aged WT mice 28 days after bleomycin injury. Green color indicates SPC expression; brown color indicates PPARα expression. Scale bars, 10 μm (n = 5 WT saline; n = 5 WT bleomycin).

(E) Quantification of percentages of double-positive cells for SPC and PPARα in the lungs of aged WT mice subjected to low-dose bleomycin after 28 days.

(F) Ppara mRNA expression was determined by qPCR in the primary AEC2 cells of patients with IPF (n = 21) compared with HP (n = 5) or COPD (n = 9).

(G) Representative multicolor immunohistological staining of PPARA and SPC. Arrows indicate examples of SPC-positive and PPARA-positive cells. Staining was performed with lung sections from 2 healthy controls and 2 patients with IPF.

(H) Quantification of percentages of double-positive cells for SPC and PPARA in the fibrotic lung regions of patients with IPF and donor (healthy) controls. Data are mean ± SEM. NS, not significant; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (for multiple group comparisons) or Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test (for two group comparisons).