Abstract

Background

Global Health opportunities are popular, with many reported benefits. There is a need however, to identify and situate Global Health competencies within postgraduate medical education. We sought to identify and map Global Health competencies to the CanMEDS framework to assess the degree of equivalency and uniqueness between them.

Methods

JBI scoping review methodology was utilized to identify relevant papers searching MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science. Studies were reviewed independently by two of three researchers according to pre-determined eligibility criteria. Included studies identified competencies in Global Health training at the postgraduate medicine level, which were then mapped to the CanMEDS framework.

Results

A total of 19 articles met criteria for inclusion (17 from literature search and two from manual reference review). We identified 36 Global Health competencies; the majority (23) aligned with CanMEDS competencies within the framework. Ten were mapped to CanMEDS roles but lacked specific key or enabling competencies, while three did not fit within the specific CanMEDS roles.

Conclusions

We mapped the identified Global Health competencies, finding broad coverage of required CanMEDS competencies. We identified additional competencies for CanMEDS committee consideration and discuss the benefits of their inclusion in future physician competency frameworks.

Abstract

Contexte

Les opportunités de santé mondiale sont populaires, avec de nombreux avantages rapportés. Il est toutefois nécessaire d’identifier et de situer les compétences en santé mondiale dans la formation médicale postdoctorale. Nous avons cherché à identifier et à mapper les compétences en santé mondiale au cadre le référentiel CanMEDS d’évaluer le degré d’équivalence et d’unicité entre elles.

Méthodologie

La méthodologie de revue exploratoire de JBI a été utilisée pour identifier les articles pertinents qui recherchent MEDLINE, Embase et Web of Science. Les études ont été examinées indépendamment par deux des trois chercheurs selon des critères d’admissibilité prédéterminés. Les études incluses ont permis d’identifier les compétences dans la formation en santé mondiale au niveau de la médecine postdoctorale, qui ont ensuite été mises en correspondance avec le cadre le référentiel CanMEDS.

Résultats

Au total, 19 articles répondaient aux critères d’inclusion (17 provenant d’une recherche documentaire et 2 d’un examen manuel des références). Nous avons identifié 36 compétences en santé mondiale; la majorité (23) correspondait aux compétences CanMEDS dans le cadre. Dix d’entre eux ont été mappés à des rôles canMEDS, mais n’avaient pas de compétences clés ou habilitantes précises, tandis que trois ne correspondaient pas aux rôles spécifiques de CanMEDS.

Conclusions

Nous avons cartographié les compétences en santé mondiale identifiées, en trouvant une large couverture des compétences CanMEDS requises. Nous avons identifié d’autres compétences à examiner par le comité CanMEDS et nous discutons des avantages de leur inclusion dans les futurs cadres de compétences des médecins.

Introduction

The popularity of Global Health experiences has soared over the last two decades. An increasing number of residency programs offer Global Health opportunities and trainees report their ranking of residency programs is influenced by the availability of these opportunities.1–5 Generally, Global Health electives are thought to increase medical knowledge and skills, improve resourcefulness and cost consciousness, influence career choices, provide insight on ethical and societal issues, and improve cross cultural communication.6–8

Global Health programs have evolved to more broadly include work to address inequities in underserved populations no matter their location, local or international. Opportunities in Global Health at the postgraduate medicine level include local or international electives, research, teaching opportunities, as well as more formalized programs of Global Health education leading to certificates. There has been substantial emphasis on ensuring electives for trainees at all levels are ethical, including the need for sustainable partnerships, appropriate supervision, the avoidance of drain on local resources, and appropriate pre-departure training. Global Health education can ensure physicians are competent in caring for patients from diverse backgrounds and across a range of resource availabilities, irrespective of the location. The use of interpreters and incorporation of advocacy, cultural safety, and social determinants of health into care are essential practices for physicians, no matter their location.

Postgraduate medical education (PGME) is shifting to competency-based training, focusing on an outcomes-based rather than time-based approach.9 The CanMEDS framework was developed in the 1990s to define the necessary competencies required by all physicians to meet the needs of society and has become the most widely applied health care professions competency framework in the world.10 Modern medical training requires physicians to be proficient beyond the role of Medical Expert, and the 2015 CanMEDS framework update specifically identifies the need for expertise in the roles of Communicator, Collaborator, Scholar, Professional, Leader, and Health Advocate.10 Much of the PGME level Global Health education literature has centered around description of program development, ethical and preparatory requirements for electives, resident interest, and perceived benefits of Global Health training. Numerous publications describe the benefit of Global Health on resident learning, from both a program and resident perspective,4,5,11–17 with one recent study on Global Health electives identifying self-perceived benefits across several of the CanMEDS roles.18 A qualitative review of resident narrative reports from Global Health electives identified competency themes, with suggested mapping to both Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies and CanMEDS roles.19 In PGME specific research, Walpole et al. developed 5 broad core competencies suggested for postgraduate UK doctors utilizing a modified policy Delphi consultation.20 Furthermore, a mixed methods study in the UK assessed Global Health training in PGME and found that minimal training was being provided according to their proposed competency framework.21

More broadly, several publications have identified curricula for Global Health education across university training programs, but not specifically focused on resident education.12,22 For example, the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) Global Health Competency Subcommittee published the Competencies Tool Kit22 which defines levels of proficiency and suggests desirable competencies for University learners across 11 domains, including global burden of disease, globalization of healthcare, social and environment determinants of health, ethics, as well as health equity and social justice. Similarly, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recently published Global Competency and Outcomes Framework for Universal Health Coverage sets out its recommended approach for competency-based health worker education outcomes to strengthen the overall health workforce education and standards of practice towards the universal provision of quality, people-centered, integrated health services.23 This framework specifically centers around the provision of primary health care and a curricular approach for health workers with pre-service training pathway of 12-48 months, including nurses, community health workers, and paramedical providers.20,21,23

Currently, limited research exists to identify specific Global Health competencies across the range of Global Health educational activities at the PGME level. We therefore sought to first identify the discrete competencies taught as part of the broader Global Health education in PGME, including experiential learning, academic partnerships, and formal Global Health curriculum. To do so, we: (i) conducted a scoping review to identify postgraduate level Global Health curricular competencies, and (ii) mapped the identified Global Health competencies onto the CanMEDS framework10 in order to identify areas where Global Health can augment current learning and help to situate the role of Global Health within CanMEDS and PGME.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to explore and summarize the available literature on Global Health education as an evolving academic field within postgraduate medicine. This scoping review was developed using the JBI approach to conducting and reporting scoping reviews, which is compliant with the PRISMA-ScR checklist.24,25 An a priori scoping review protocol was developed, outlining how we a) developed the research question; b) identified the relevant studies; c) selected the studies; d) extracted the data; e) analyzed and presented the results. An exemption to seek REB review was obtained from the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board.

Developing the research question

We sought to identify and analyse PGME competencies that could be achieved through Global Health education. We limited the research question to Global Health education at the PGME level but did not restrict the country in which the education occurred in order to assess a breadth of postgraduate Global Health curriculum designs.

Identifying the relevant studies

We conducted our searches with the assistance of an experienced University Research Librarian. An initial limited search was performed to identify keywords and index terms used to identify relevant articles of interest. We then searched the following databases, with the identified MeSH and free text terms: MEDLINE (Ovid; inception – Feb 3, 2022); Embase (inception – Feb 3, 2022); and Web of Science (inception – Feb 3, 2022). With our interest being PGME, we limited the focus to the selected medical databases and included a comprehensive keyword search strategy in Web of Science to identify additional articles in multi-disciplinary and medical education journals as well as grey literature such as conference proceedings or guidelines. We excluded reviews, opinions, and editorials as our goal was to obtain primary literature. We included no limitations on language or country of publication. As a third step, we identified additional relevant articles by searching the reference lists of included manuscripts.

Selecting the data

Independent screening was conducted by three authors (AS, JP, SA); screening required two reviewers to agree on inclusion in order to proceed, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. COVIDENCE software was utilized to organize and track the screening process. Articles were included if they were relevant to discrete educational competencies at the postgraduate medicine level, for trainees of any specialty, and were identified within Global Health curriculum. We did not include a formal quality assessment of each article, given the nature and purpose of the scoping review.

Extracting the data

Reviewers (AS, SA) independently analyzed and extracted data from full-text articles into a charting table to minimize chance of errors or bias. A draft charting table was developed to include key information such as author, reference, country, year, and list of competencies identified. The independent data extraction tables were reviewed (JP), and a master document was completed by consensus.

Analysis and presentation of results

Global Health competencies were identified and mapped to the CanMEDS framework’s roles, key competencies, and enabling competencies where possible.

Results

Scoping review

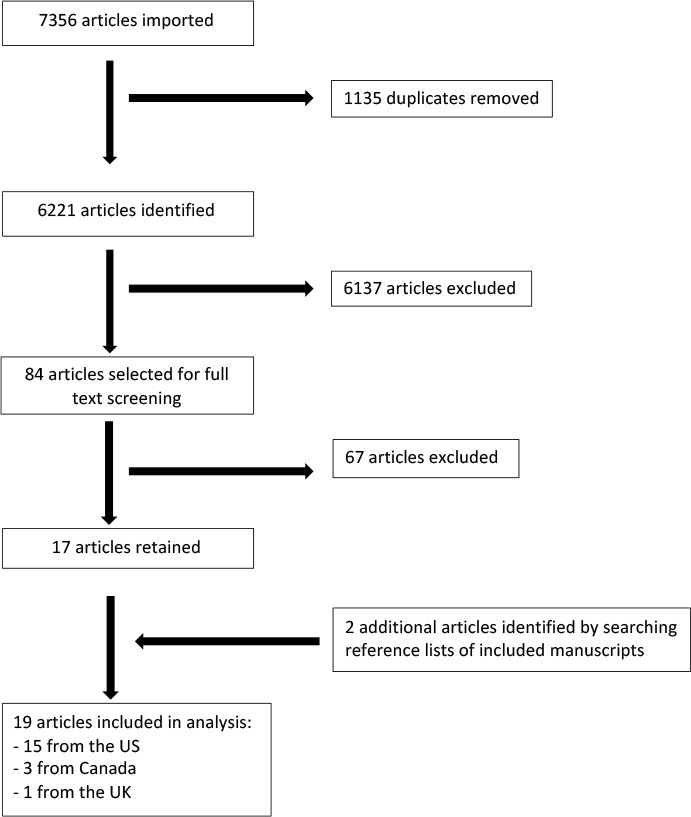

Figure 1 (PRISMA) shows the literature review and selection process. Eighty-four articles were selected for full-text review from 6221 articles identified in the initial search. Of those 84, 17 full-text articles were selected for full analysis. Two additional full-text articles were included after manual search of reference lists from selected articles. The year of publication ranged from 2008-2018, with the majority (15 studies) from the US, three from Canada, and one from the UK. Importantly, there was a lack of studies originating in low-middle-income countries (LMIC). Methodologies mainly included a combination of literature review and expert consensus, with some incorporating modified Delphi technique or surveys.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram

Table 1 lists the 36 Global Health competencies identified during our scoping review. Several papers listed their Global Health competencies based on ACGME or CanMEDS competencies, therefore key sub-competencies and detailed competency examples were utilized to compile our list of discrete Global Health competencies.

Table 1.

List of Global Health Competencies

| Capacity strengthening | Health & psychological impact of conflict | Medical knowledge |

| Collaboration & partnership | Health advocate | Nutrition |

| Communicating through a translator | Health disparities | Patient care |

| Communication | Health equity, diversity, human rights & social justice | Personal & professional development |

| Contributors to morbidity & impaired cognition in LMICs | Health policy | Practice based learning & improvement |

| Cultural competency | Healthcare needs assessment, project development & evaluation | Professionalism/professional practice |

| Epidemiology, research & evaluation skills | Human rights | Scholar |

| Ethics | Identify & apply standardized guidelines | Social, economic, political & environmental determinants of health |

| Ethics in international research | Interaction of environment & health | Sociocultural & political awareness |

| Global burden of disease | Interpersonal & communication skills | Strategic analysis |

| Global health governance | Interrelationship between health, human rights, and social & gender inequities Manager/program management |

Systems based practice |

| Globalization of health & healthcare | Tropical, travel medicine & infectious disease | |

Mapping to CanMEDS competencies

The Global Health competencies identified were subsequently mapped to the CanMEDS framework’s seven individual roles (Medical Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Leader, Health Advocate, Scholar, and Professional), then matched to the corresponding detailed key competencies and then enabling competencies within the framework.

The Global Health competencies identified in our scoping review covered the majority of CanMEDS key competencies. Some of the Global Health competencies described in the papers retrieved were broad in nature, especially those that were written to fit into ACGME or CanMEDS competencies. This meant that we had to examine the listed sub-competencies or pull further details from the examples given for each broad competency to derive meaning & map to specific key and enabling competencies. Given the breadth of knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for competency in Global Health work, the broad coverage of CanMEDS competencies is not surprising.

We identified two CanMEDS key competencies that did not have a Global Health competency mapped to them: 4. Manage career planning, finances, and health human resources in a practice under the Leadership role and 3. Demonstrate a commitment to the profession by adhering to standards and participating in physician-led regulation under the Professional role, which may reflect the variation in physician regulation, remuneration, and practice environment in Global Health settings. Even in the Canadian healthcare context, the requirements to individually manage finances and human resources are greatly varied from running an independent office practice to being remunerated based on hours worked.

Our Global Health competency mapping also identified items which are absent from the CanMEDS framework. Table 2 illustrates the thirteen Global Health competencies for which there was no equivalent CanMEDS key or enabling competency. Ten of these competencies could be mapped to CanMEDS roles while three competencies were less fitting within CanMEDS roles and have been classified as “other” for the purposes of this study.

Table 2.

Global Health Competencies without CanMEDS equivalent

| CanMEDS Role | Global Health Competencies |

|---|---|

| Communicator | Communicating through a translator |

| Health Advocate | Health equity, diversity, human rights & social justice |

| Medical Expert | Global burden of disease |

| Interrelationship between health, human rights, and social and gender inequities | |

| Health & psychological impact of conflict | |

| Interaction of environment & health | |

| Tropical, travel medicine, & infectious disease | |

| Nutrition | |

| Identify & apply standardized guidelines | |

| Contributors to morbidity and impaired cognition in LMICs | |

| Other | Globalization of health & healthcare |

| Sociocultural & political awareness | |

| Health policy |

Discussion

In this study, we have (i) conducted a scoping review to identify a discrete list of Global Health competencies targeted for PGME, and (ii) mapped the identified competencies to the CanMEDS framework. Further, we have identified Global Health competencies which are currently absent from the CanMEDS framework for consideration.

Given the rising numbers of programs seeking to implement Global Health curriculum within residency and fellowship education, our scoping review informs the groundwork for the development of a competency-based curriculum, adding to previous work in Global Health education more broadly. Global Health competencies could help facilitate residents’ learning and experience, particularly in geographic areas that have less diverse patient populations and opportunities. The mapping of Global Health competencies to the CanMEDS framework serves as a basis for the future development of specific milestones and entrustable professional activities. Global Health competencies can be used not only by those implementing Global Health curriculum but by all PGME programs and would further incorporate competencies concentrating on understanding complex structural and social factors that affect patient and population health.

Overall, the Global Health competencies identified in our scoping review mapped well to the CanMEDS framework. We identified ten Global Health competencies which mapped to CanMEDS roles but lacked an equivalent key or enabling competency. An additional three Global Health competencies did not have a good fit within the CanMEDS roles. The Global Health list of competencies provides specific emphasis on some competencies required of physicians working in Global Health, which may not traditionally have been envisioned as core physician competency needs. We feel that the identification of these competencies in our research is an opportunity for reflection on their appropriateness for inclusion in future iterations of the CanMEDS framework.

Communicating through a translator is identified as a unique skill in communication within the Global Health competency list, which is not specifically included in the CanMEDS competencies.

Physicians in the CanMEDS10 Communicator role ‘form relationships with patients and their families that facilitate the gathering and sharing of essential information for effective health care’ (p. 16). Given the recognized need for effective information exchange, and the frequency with which physicians encounter patients and their families whose language does not align with that of the physician, we feel that this should strongly be considered for incorporation into future iterations of CanMEDS competencies to allow for safe, effective, patient-centered care. Similarly, the absence of attention on equity, diversity, and inclusion within the CanMEDS Health Advocate role, covered in the Global Health competency Health equity, diversity, human rights, and social justice, is a gap which recent literature has explored and should inform future competency refinements.26–28 While the Global Health competency understanding the interrelationship between health, human rights, and social and gender inequities encompasses aspects under the CanMEDS Medical Expert role, it also draws upon the Health Advocate role and would benefit from future inclusion into a more equity-focused competency framework.

Unsurprisingly, multiple Global Health competencies mapped to the Medical Expert role, central to the CanMEDS framework, but demonstrated unique and unmatched competencies. Global burden of disease entails an understanding of major causes of morbidity and mortality, variation between countries, the influence of demographics, and awareness of public health strategies to reduce disparities such as the Sustainable Development Goals. The Global Health competency requiring knowledge of contributors to morbidity and impaired cognition in low-middle-income countries, was also identified as absent from the CanMEDS framework. Given inequities within Canada and the number of immigrants and refugees present, one could argue that both of these Global Health competencies should be included in physician training. The interaction of environment and health identified among the Global Health competencies should require little convincing for inclusion into the CanMEDS framework, given the widespread global acceptance around the significant and multifaceted impacts of the environment on health. The Global Health competency to identify and apply standardized guidelines requires the knowledge to identify guidelines and adapt them to individual patients as well as locate resources and guidelines for care in resource-limited settings or humanitarian emergencies. While some detailed aspects of guidelines may not be relevant in the Canadian context, we feel that a basic awareness of and ability to locate high quality guidelines from recognized international organizations is important. Guidelines, such as those by the World Health Organization, provide guidance in settings or for diseases unfamiliar to Canadian physicians, while others recognize the work towards the professionalization of the humanitarian response sector to enhance effective and ethical care and minimize harm.29,30

Other Global Health competencies under the Medical Expert role centered on specific medical knowledge. Recognizing the impacts of displacement, war, torture, human trafficking, gender-based violence, child soldiers, and child labour, among others, is at the core of the health and psychological impact of conflict Global Health competency. Several of these issues, particularly gender-based violence and human trafficking, remain underrecognized within Canada.31 Given the diverse refugee and immigrant populations in Canada who have been impacted by persecution, violence, and conflict, and the under-recognized prevalence of human trafficking and gender-based violence within Canada, we argue that there is a role for a basic competency which includes recognition and knowledge of appropriate referral resources for affected patients and their families. The final Global Health competencies that map to the CanMEDS Medical Expert role are tropical, travel medicine and infectious disease and nutrition. These specific topics including malaria, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), parasitic infections, chronic and acute malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency, and disease prevention in travellers. Given the prevalence of some infectious diseases and malnutrition within regions of and specific populations in Canada (including refugees and immigrants, indigenous communities, those with low socioeconomic status, underhoused, or living in crowded or institutional conditions) we feel that all physicians would benefit from a basic understanding of these competencies.

Three Global Health competencies had a less clear direct mapping to CanMEDS roles. Health policy and globalization of health and healthcare competencies identify how policy, expenditures, and globalization, including the effects of travel, worker availability and migration, affect health systems and healthcare provision. The sociocultural and political awareness competency requires skills to work effectively within diverse cultural, political, and geographic settings. Together these competencies would provide a better understanding of the influences on patient health and healthcare provision regardless of location. Integrating required understanding of broad influences on healthcare would benefit overall physician competency and provide additional knowledge for the Health Advocate role.

Our scoping review was specifically limited to examine the identified competencies in PGME Global Health education. The literature retrieved does not examine how Global Health competencies should be taught, the analysis of which is outside of the scope of this paper. Evaluating how Global Health medical education moves from discussing decolonializing theory to curriculum design and implementation is an important area of research missing from the current literature but ripe for higher level medical education scholarship. Interestingly none of the papers specifically include the need for a decolonizing approach to Global Health education, perhaps due to the recency of many calls to scrutinize current practice models of Global Health. Several of the included papers explicitly mentioned the importance of both ‘local’ and international Global Health as well as the need for socio-cultural awareness. This attention towards identifying and addressing inequalities in health, wherever they exist, would help ensure that these inequities are not unwittingly taught as being ‘others’ issues from a predominantly white, high-income, colonial viewpoint while overlooking similar disparities that exist within our own communities in Canada.

There is much interest from residents in Global Health education and experiences. This study provides a summary of the discrete competencies taught in postgraduate Global Health education, outlines how they map to the CanMEDS framework, and identifies areas of alignment as well as opportunities for further enhancement at the PGME level. The additional competencies identified in our Global Health competency scoping review, if included in future CanMEDS frameworks, would enrich resident education and ensure the competency of physicians preparing to work in today’s practice environment, in a highly globalized and interconnected world.

Limitations

Our study contains several limitations. Despite setting no limits in our scoping review strategy for country or language, we retrieved only papers in English from the US, UK, and Canada, reflecting high-income country, traditionally colonial perspectives of Global Health education and sending, not receiving, residents for electives. This might reflect bias on behalf of journals for selection of articles to publish, prohibitive publication costs for authors from LMICs, or indexing of journals into the selected databases. Global Health research has been dominated by authors from high-income countries (HICs), despite focusing intently on LMIC settings.32 Factors that have been cited as barriers to LMIC-driven research and publication include unequal stakes in setting research agendas, a lack of funding, and a lack of access to infrastructure.33 Our scoping review results reflect an ongoing phenomenon of Global Health discourse perpetuating colonial structures of inequality between the Global North and the Global South.34 Historically, Global Health initiatives have exacerbated unequal partnerships where Global North parties unilaterally determine research priorities and accumulate data without acknowledgement of, and at times at the cost of, their Global South partners.35 There has been increasing discourse around decolonizing Global Health, including reframing educational paradigms to facilitate better reciprocal relationships between centres of learning.34,36 However, theoretical frameworks and practical applications of decolonizing Global health education are still contested.37,38 None of the included articles explicitly referenced decolonizing strategies, though multiple authors specifically sought input from LMIC partners and identified competencies based in concepts of cultural humility.22,39–41 Ultimately, we find that our study re-illustrates the power differentials between the Global North and Global South existing in the field of Global Health. Applying a decolonizing lens to medical education competencies would not only serve to address the potential harms of Global Health practice in international contexts but is also relevant to local settings. The ongoing legacy of colonialism in Canada continues to be an issue to be contended with, particularly with its implications in medical practice.42,43 Future iterations of CanMEDS competencies can not only incorporate concepts of equity and diversity, but should also attempt to deconstruct colonial ways of thinking. We agree with calls for curriculum to include the manifestations and consequences of racism and colonisation in Global Health, adding a call for the same within the Canadian context, and the need for curriculum emphasis on decolonizing, anti-oppression, antiracism, and allyship.38 The addition of these concepts into the CanMEDS framework would serve to strengthen all roles, but particularly that of Health Advocate, Professional, and Scholar. Consideration should also be given to the best method of assessment for non-medical expert roles within the CanMEDS framework to evaluate these important competencies. Non-psychometric based assessment tools, such as realist and ethnographic methods, have been suggested as improved ways to assess competencies that require socio-cultural understanding.44

We limited our scoping review to PGME competencies in global Health. The results yielded only papers from HICs which could be due to a bias in the use of competency frameworks or publication of discussion of these frameworks in LMICs. CanMEDS is, however, one of the most widely used competency frameworks, utilized by over 50 jurisdictions and at least 12 professions across the world, including a smaller but growing number of LMICs.45 It has been studied for implementation outside of the Canadian setting in several countries.46–48 One study exploring ways to harmonize curriculum across national borders suggested that harmonization of outcome frameworks can be achieved by a 2-level approach with 1) global level core competencies and 2) secondary competencies that allowed for local adaptation based on local learning styles, culture, and other contextual factors.49 Several studies have suggested the overall utility or validity of the CanMEDS framework but identify a need for adaptations to specialty or cultural expectations.46,47 While current competency frameworks utilized in HICs have been criticized for their narrow scope,38 they could be used as the foundation for an improved approach to Global Health education. Inclusion of curricula addressing the manifestations of racism and coloniality, interdisciplinary content, collaboration with LMIC and other traditionally under-represented stakeholders and an emphasis on participatory approaches to ‘local’ Global Health would benefit residency education across the CanMEDS framework.

Several of the articles utilized ACGME or CanMEDS competencies as the overarching framework for discussing their Global Health competencies and so we drew from listed sub-competencies and examples provided to develop our detailed list of Global Health competencies. Without consulting experts from diverse backgrounds, we may have missed highlighting specific competencies. This could be a step for future research to develop a set of universal Global Health PGME competencies, including the incorporation of best practices in Global Health partnerships and education with specific attention to a decolonized approach to Global Health. Additionally, the papers we retrieved focused on Global Health in general and not on ‘local’ Global Health education specifically. We recognize the inequities and systemic racism within Canada and that a focus on Global Health should enhance and not detract from addressing these. We therefore call for a greater emphasis on understanding and addressing Canada’s inequities and systemic racism as a part of the CanMEDS competencies. Given that not all residents can or wish to participate in international work or experiences due to financial, family, or other factors, competencies for local Global Health work concentrating on underserved and vulnerable populations within Canada would be valuable, recognizing that there is an additive benefit to incorporating experiential learning when engaging in these complex competencies.

Conclusion

Our scoping review identified a list of discrete Global Health competencies. We have mapped these competencies to the CanMEDS framework and demonstrated that Global Health competencies cover the breadth of required CanMEDS competencies. Further research should examine the best ways to integrate Global Health competencies into residency education and to establish and operationalize a decolonizing approach to Global Health. We also identified opportunities for enhancement of current CanMEDS competencies in order to prepare physicians for practice in a diverse and interconnected world.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sandra McKeown, librarian at Queen’s University, for her support in developing the search strategy and protocol.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was required to complete this study. Jodie Pritchard is the recipient of a one-year Southeastern Ontario Academic Medical Organization (SEAMO) clinical research fellowship to provide salary support towards scholarly research in Global Health. SEAMO had no input into the research selection, design, or results.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Dey CC, Grabowski JG, Gebreyes K, Hsu E, VanRooyen MJ. Influence of international emergency medicine opportunities on residency program selection. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9(7):679-83. 10.1197/aemj.9.7.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaeppler C, Holmberg P, Tam RP, et al. The impact of global health opportunities on residency selection. BMC Med Educ. 2021. Dec 1;21(1). 10.1186/s12909-021-02795-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson KH, Bowder AN, Goldblatt MI, Olson L, Dodgion CM. General surgery applicants are interested in global surgery, but does it affect their rank list? J Surg Res. 2021. Jan 1;257:449-54. 10.1016/j.jss.2020.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Dan Hunt D, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on u.s. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Vol. 78, Acad. Med. 2003. 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu PM, Park EE, Rabin TL, et al. Impact of global health electives on us medical residents: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health. 2018. Nov 5;84(4):692-703. 10.29024/aogh.2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litzelman DK, Gardner A, Einterz RM, et al. Correction: on becoming a global citizen: transformative learning through global health experiences (Annals of Global Health. 2017. May-August; 83(3-4): 596-604. Vol. 87, Annals of Global Health. Ubiquity Press; 2021. 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawatsky AP, Rosenman DJ, Merry SP, McDonald FS. Eight years of the Mayo International Health Program: what an international elective adds to resident education. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):734-41. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate O ten, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010. Aug;32(8):638-45. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. 35 p.

- 11.Volsky PG, Sinacori JT. Global health initiatives of US otolaryngology residency programs: 2011 global health initiatives survey results. Laryngoscope. 2012. Nov;122(11):2422-7. 10.1002/lary.23533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schleiff M, Hansoti B, Akridge A, et al. Implementation of global health competencies: a scoping review on target audiences, levels, and pedagogy and assessment strategies. PLoS One. 2020. Oct 1;15(10 October). 10.1371/journal.pone.0239917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salasky VR, Saylor D. Impact of Global Health Electives on Neurology Trainees. Ann Neurol. 2021. May 1;89(5):851-5. 10.1002/ana.26031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez A, Ho T, Verheyden C. International programs in the education of residents: benefits for the resident and the home program. J Craniofacial Surg. 2015;26(8):2283-6. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauden SM, Gladding S, Slusher TM, Howard CR, Pitt MB. Thematic analysis of global health trainee experiences with mapping to core competencies (research abstract). Acad Pediatr. 2017. Jul;17(5):e48-9. 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohlman L, DiMeglio M, Laudanski K. The impact of an international elective on anesthesiology residents as assessed by a longitudinal study. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019. Jan;6:238212051987394. 10.1177/2382120519873940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Posid T, Amin S, Kaufman L, et al. MP67-08 urology patient perceptions of resident cultural competency in a pilot local global health curriculum. 2021. 10.1097/JU.0000000000002028.08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanys A, Krikler G, Spitzer RF. The impact of a global health elective on CanMEDS competencies and future practice. Hum Resour Health. 2020. Jan 29;18(1). 10.1186/s12960-020-0447-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordhues HC, Bashir MU, Merry SP, Sawatsky AP. Graduate medical education competencies for international health electives: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2017. Nov 2;39(11):1128-37. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1361518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walpole SC, Shortall C, van Schalkwyk MC, et al. Time to go global: a consultation on global health competencies for postgraduate doctors. Int Health. 2016. Sep 1;8(5):317-23. 10.1093/inthealth/ihw019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Shakarchi N, Obolensky L, Walpole S, Hemingway H, Banerjee A. Global health competencies in UK postgraduate medical training: a scoping review and curricular content analysis. BMJ Open. 2019. Aug 1;9(8). 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) Competency sub-committee . CUGH Global Health Education competencies tool kit (2nd edition). Washington, DC; 2018. Available from: www.cugh.org/onlne-tools/competencies-toolkit/ [Accessed on Mar 26, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . Global competency and outcomes framework for universal health coverage [Internet]. Geneva; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034686 [Accessed on Jul 24, 2022]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020. Oct 1;18(10):2119-26. 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aromataris E, Munn Z (editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald M, Lavelle C, Wen M, Sherbino J, Hulme J. The state of health advocacy training in postgraduate medical education: a scoping review. Vol. 53, Med Ed. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2019. p. 1209-20. 10.1111/medu.13929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryan JM, Alavian S, Giffin D, et al. CAEP 2021 Academic symposium: recommendations for addressing racism and colonialism in emergency medicine. Can J Emerg Med. Springer Nature; 2022. p. 144-50. 10.1007/s43678-021-00244-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLane P, Bill L, Barnabe C. First Nations members' emergency department experiences in Alberta: a qualitative study. Can J Emerg Med. 2021. Jan 1;23(1):63-74. 10.1007/s43678-020-00009-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson K, Idzerda L, Baras R, et al. Competency-based standardized training for humanitarian providers: making humanitarian assistance a professional discipline. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(4):369-72. 10.1017/dmp.2013.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . Emergency medical teams initiative: about us [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/emt/content/about-us [Accessed on Apr 29, 2022].

- 31.Froutan Aziz . Concern is not enough: while human trafficking continues to tear lives apart, new research reveals canadians are shockingly unaware of the realities or how to make a difference. The Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking. 2021. Available from: https://www.canadiancentretoendhumantrafficking.ca/concern-is-not-enough-while-human-trafficking-continues-to-tear-lives-apart-new-research-reveals-canadians-are-shockingly-unaware-of-the-realities-or-how-to-make-a-difference/ [Accessed on Apr 29, 2022].

- 32.Mbaye R, Gebeyehu R, Hossmann S, et al. Who is telling the story? A systematic review of authorship for infectious disease research conducted in Africa, 1980-2016. BMJ Glob Health. 2019. Oct 1;4(5). 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chu KM, Jayaraman S, Kyamanywa P, Ntakiyiruta G. Building research capacity in Africa: equity and global health collaborations. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3). 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naidu T. Southern exposure: levelling the Northern tilt in global medical and medical humanities education. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2021. May 1;26(2):739-52. 10.1007/s10459-020-09976-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edejer TTT. North-South research partnerships: the ethics of carrying out research in developing countries. BMJ. 1999. Aug 14;319(7207):438-41. 10.1136/bmj.319.7207.438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eichbaum QG, Adams Lv, Evert J, Ho MJ, Semali IA, van Schalkwyk SC. Decolonizing global health education: rethinking institutional partnerships and approaches. Vol. 96, Acad Med. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2021. p. 329-35. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhuri MM, Mkumba L, Raveendran Y, Smith RD. Decolonising global health: Beyond “reformative” roadmaps and towards decolonial thought. Vol. 6, BMJ Global Health; 2021. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sayegh H, Harden C, Khan H, et al. Global health education in high-income countries: confronting coloniality and power asymmetry. BMJ Global Health. 2022. May;7(5):e8501. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen CCG, Dougherty A, Whetstone S, et al. Competency-based objectives in global underserved women's health for medical trainees. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017. Oct 1;130(4):836-42. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asgary R, Smith CL, Sckell B, Paccione G. Teaching immigrant and refugee health to residents: domestic global health. Teach Learn Med. 2013. Jul;25(3):258-65. 10.1080/10401334.2013.801773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arora G, Condurache T, Batra M, et al. Miles away milestones: a framework for assessment of pediatric residents during global health rotations. Acad Pediatr. 2017. Jul 1;17(5):577-9. 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada . Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: calls to action. [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.801236/publication.html [Accessed on Aug 12, 2022].

- 43.Shaheen-Hussain S. Fighting for a hand to hold: Confronting medical colonialism against Indigenous children in Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitehead CR, Kuper A, Hodges B, Ellaway R. Conceptual and practical challenges in the assessment of physician competencies. Vol. 37, Med Teach. Informa Healthcare; 2015. p. 245-51. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.993599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thoma B, Karwowska A, Samson L, et al. Emerging concepts in the CanMEDS physician competency framework. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ringsted C, Hansen TL, Davis D, Scherpbier A. Are some of the challenging aspects of the CanMEDS roles valid outside Canada? Med Educ. 2006. Aug;40(8):807-15. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afr Anaesth Analg SJ. Defining fitness for purpose in South African anaesthesiologists using a Delphi technique to assess the CanMEDS framework. South. African J Anaesth Analg 2019;25(2):7-16. 10.36303/SAJAA.2019.25.2.2193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner S, Seel M, Trotter T, et al. Defining a Leader Role curriculum for radiation oncology: a global Delphi consensus study. J Radiat Oncol. 2017. May 1;123(2):331-6. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hautz SC, Hautz WE, Feufel MA, Spies CD. Comparability of outcome frameworks in medical education: implications for framework development. Med Teach. 2015. Nov 2;37(11):1051-9. 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1012490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]