INTRODUCTION

The benefits and effectiveness of community health workers’ (CHWs) support of diabetes patients are well established.1,2 Less is known about the effectiveness in rural settings, although there is some evidence that CHWs can improve clinical outcomes.3,4 Patient-reported outcomes such as self-management activities (e.g., healthy eating, exercise) and self-efficacy (e.g., confidence) are not widely reported in studies of rural CHW programs.4 This brief research report shares the clinical and patient-reported outcomes of patients with diabetes in a rural Kentucky CHW model.

POPULATION AND METHODS

Mountain Comprehensive Health Corporation (MCHC) is a non-profit network of federally qualified health centers that serves over 40,000 patients annually throughout rural, Southeastern Kentucky. MCHC developed a partnership with Marshall University, which has supported rural federally qualified health centers in leveraging available Medicaid reimbursement for CHW services.3 MCHC and Marshall University are part of the Merck Foundation’s Bridging the Gap: Reducing Disparities in Diabetes Care initiative. MCHC implemented a CHW program to support diabetes care of patients who have multiple chronic conditions and face significant medical and social care barriers (e.g., transportation, healthy food access).

HbA1c measures and patient-reported outcomes were collected among patients who received at least 6 months of MCHC CHW engagement and at least 1 year of follow-up data. A 22-item survey was administered that covered diabetes self-management activities, self-efficacy, quality of life, and patient experience at baseline and 12 months. HbA1c values were extracted from the electronic medical record for patients enrolled between December 2017 and July 2021. CHWs entered surveys into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database.5 Paired t tests, McNemar’s tests, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to evaluate differences between patient-reported outcomes at baseline and 12 months. Linear mixed models were used to evaluate HbA1c changes over time.

RESULTS

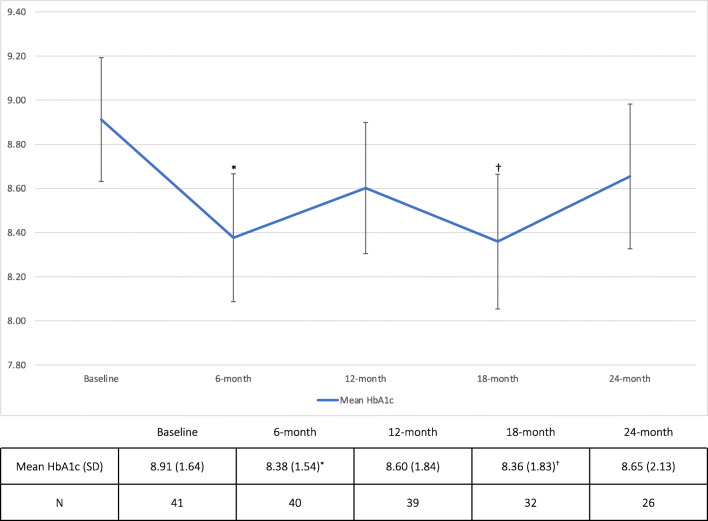

Sixty-three patients with diabetes were identified who engaged with the MCHC CHW model. Patients were white (100%), predominantly female (59%), over 65 (54%), and covered by Medicare (44%) or Medicaid (36%) or were dual-eligible (19%), and spoke English (100%). Patients with patient-reported outcomes surveys at baseline and 12 months (n = 28) did not differ in demographic and clinical characteristics from the whole population. Patients engaged with MCHC CHWs reported improvements in self-efficacy and were confident in managing diabetes during hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia (p = 0.02) and confident that diabetes would not be interfering with their lives (p = 0.005) (Table 1). There was a trend for patients to report improved confidence in choosing healthier foods (p = 0.08). Patients reported improved communication experiences with their primary care providers (PCPs) over time, but these did not meet statistical significance. There were improvements in quality of life measures (e.g., reductions in days reporting not good physical health, days reporting not good mental health), but no changes met significance. Baseline HbA1c levels decreased from 8.91% (1.64) to 8.38% (1.54) at 6 months (p = 0.04) (Fig. 1). There was a trend in HbA1c improvement to 8.36% (1.83) at 18 months (p = 0.09).

Table 1.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Rural Patients Engaged in CHW Model (n = 28)

| Baseline mean (SD) | 12 months mean (SD) | Change mean (SD) | p value | |

| Self-management behaviors | ||||

| Days per week with healthful eating | 4.3 (2.2) | 4.2 (2.4) | − 0.1 (2.5) | 0.880 |

| Days per week with fruits and vegetables | 4.4 (1.9) | 4.8 (2.1) | 0.4 (2.3) | 0.367 |

| Days per week with high-fat foods | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.7 (2.0) | 0.1 (2.4) | 0.752 |

| Days per week of meeting exercise | 3.7 (2.5) | 4.4 (2.3) | 0.7 (3.2) | 0.270 |

| Days per week testing blood sugar | 6.8 (1.0) | 6.8 (1.1) | 0.0 (1.5) | 1.000 |

| Days per week testing blood sugar per provider recommendations | 6.8 (0.8) | 6.5 (1.6) | − 0.3 (1.5) | 0.302 |

| Days per week taking meds as prescribed | 6.9 (0.8) | 7.0 (0) | 0.1 (0.8) | 0.326 |

| Days per week checking feet | 5.6 (2.3) | 6.1 (1.8) | 0.6 (2.6) | 0.263 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages per day | 0.9 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.1) | − 0.2 (1.4) | 0.407 |

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| Confidence in choosing healthy foods | 6.3 (2.7) | 7.3 (2.1)† | 0.9 (2.7) | 0.075 |

| Confidence in exercising | 6.0 (3.3) | 7.0 (3.2) | 1.0 (3.5) | 0.144 |

| Confidence when blood sugar goes high or low | 7.9 (2.5) | 9.2 (1.3)* | 1.3 (2.7) | 0.017 |

| Confidence in diabetes not interfering | 6.4 (2.5) | 8.2 (1.8)* | 1.8 (3.1) | 0.005 |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Days of the last 30 when physical health is not good | 13.1 (10.7) | 10.0 (10.9) | − 3.0 (13.6) | 0.249 |

| Days of the last 30 when mental health is not good | 9.3 (11.0) | 6.4 (8.2) | − 3.0 (11.6) | 0.187 |

| Days of the last 30 when physical or mental health impacts life | 11.2 (12.7) | 8.9 (11.1) | − 2.3 (15.4) | 0.467 |

| Days of the last 30 when pain makes it hard for usual activities | 7.8 (12.1) | 7.1 (10.7) | − 0.7 (16.1) | 0.817 |

| n (%) | n (%) | p value | ||

| Self-rated health (e.g., good, very good, excellent) | 14 (50) | 14 (50) | – | 0.732 |

| Same health, or better, as 6 months ago | 22 (79) | 21 (75) | – | 0.120 |

| Limited by health | 17 (61) | 15 (54) | – | 0.773 |

| Patient experience | ||||

| PCP discusses work or life (e.g., always, usually) | 21 (75) | 23 (82) | – | 0.139 |

| PCP asks your ideas about your care (e.g., always, usually) | 18 (64) | 21 (75) | – | 0.179 |

Note: Paired t tests, McNemar’s tests, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to evaluate differences between patient-reported outcomes at baseline and 12 months. Change values in italics represent improvements from baseline across patients; values in bold represent worsening outcomes from baseline across patients. Full survey is available as an appendix in Wang G, Gauthier R, Gunter KE, et al. Improving diabetes care through population health innovations and payments: lessons from Western Maryland. In preparation for Journal of General Internal Medicine Supplement; 2022

CHW community health worker, PCP primary care provider

*Denotes significant improvement from baseline (p < 0.05)

†Denotes trend in improvement from baseline (p < 0.10)

Figure 1.

HbA1c outcomes among MCHC patients engaged with community health workers. Abbreviation: MCHC—Mountain Comprehensive Health Corporation. *Denotes significant improvement from baseline (p < 0.05). †Denotes trend in improvement from baseline (p < 0.10).

DISCUSSION

The MCHC CHW model bridges gaps in diabetes care by engaging patients in ways that meet their needs and address barriers in rural areas (e.g., transportation, healthcare access). Patients engaged with MCHC CHWs saw improvements in self-efficacy in managing their diabetes, but not in self-management behaviors like healthy eating or exercise. Self-efficacy, or confidence, is an important precursor to behavior change.6 Study participants may have had improvements in confidence that had not yet manifested in actual self-management behaviors, particularly given barriers to self-management in low-income, rural settings. Participants reported that their PCPs were more likely to ask about their lives and their ideas about their healthcare over time, but these changes were not statistically significant.

Although there was no significant improvement across all measures, signals of improvement were observed across 17 of 22 items. These data underscore the importance of CHW support that addresses patient needs (e.g., self-management support, healthcare access) while considering some of their potential worries (e.g., confidence, pain). Statistically significant improvements in glycemic control persisted at 18 months after initial improvement at 6 months. CHWs may have navigated patients to additional medical services (e.g., prescription medication, primary care) that facilitated these improvements in glycemic control.

This study has limitations. Our sample was small, and program attrition made follow-up survey completion difficult, further limiting size and power to detect statistically significant changes. Our sample also exclusively identified as white, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings.

While patient-reported outcomes are underreported in current literature, these measures provide worthwhile contextual understanding of chronic disease management among patients and the clinical improvements observed after engagement with a rural CHW model.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Teresa Mimes, MA, and Melinda Boggs, MA, for their pivotal roles as CHWs at MCHC as well as leading survey collection for the study; Stephanie Bowman, MSN, FNP-C, DCES, at Marshall University for her guidance throughout project implementation, and Tammy Collett, RN, for her leadership supporting the MCHC CHW program.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jacob P. Tanumihardjo, Email: jtanumihardjo@uchicago.edu.

Chasity Eversole, Email: ceversole@mtncomp.org.

References

- 1.Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, et al. Outcomes at 18 months from a community health worker and peer leader diabetes self-management program for Latino adults. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):1414–1422. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, et al. Patient-centered community health worker intervention to improve posthospital outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):535–543. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crespo R, Christiansen M, Tieman K, Wittberg R. An emerging model for community health worker-based chronic care management for patients with high health care costs in rural Appalachia. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E13. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.190316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feltner F, Thompson S, Baker W, Slone M. Community health workers improving diabetes outcomes in a rural Appalachian population. Soc Work Health Care. 2017;56(2):115–123. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2016.1263269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]