Abstract

Background

Human Immuno-deficiency Virus (HIV) infection and antiretroviral therapy (ART) can cause metabolic disorders such as lipodystrophy, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, all of which are symptoms of metabolic syndrome (MetS). In Ethiopia, despite the existence of the primary studies, there was no pooled study conducted to summarize the country-level MetS among people living with HIV (PLHIV). Therefore, this study aims to estimate the pooled prevalence of MetS among PLHIV in Ethiopia.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted to retrieve studies on the prevalence of MetS among PLHIV in Ethiopia from PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Web of Sciences, HINARI, and other relevant sources. A random-effects model was used to estimate the MetS in this study. The overall variation between studies was checked by the heterogeneity test (I2). The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria were used to assess the quality of the studies. The summary estimates were presented with forest plots and tables. Publication bias was checked with the funnel plot and Egger’s regression test.

Results

Overall, 366 articles were identified and evaluated using the PRISMA guidelines, with 10 studies meeting the inclusion criteria included in the final analysis. The pooled prevalence of MetS among PLHIV in Ethiopia was 21.7% (95% CI:19.36–24.04) using National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP/ATP III) and 29.91% (95% CI: 21.54–38.28) using International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria. The lowest and highest prevalence of MetS were 19.14% (95%CI: 15.63–22.64) and 25.6% (95%CI: 20.18–31.08) at Southern Nation and Nationality People Region (SNNPR) and Addis Ababa, respectively. There was no statistical evidence of publication bias in both NCEP-ATP III and IDF pooled estimates.

Conclusion

MetS was common among PLHIV in Ethiopia. Therefore, optimizing regular screening for MetS components and promoting a healthy lifestyle is suggested for PLHIV. Furthermore, more study is contributory to identify the barriers to implementing planned interventions and meeting recommended treatment goals. Trial registration: The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42023403786.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-023-01034-9.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, HIV/AIDS, Ethiopia, Meta analysis

Background

World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that HIV/AIDS remains a major global public health concern, having claimed the lives of 40.1 million [33.6–48.6 million] people to date. In 2021, HIV-related causes killed 650,000 [510,000-860,000] people, and 1.5 million [1.1-2.0 million] were newly infected. Furthermore, approximately 38.4 million [33.9–43.8 million] people were living with HIV at the end of 2021, with the WHO African Region accounting for two-thirds (25.6 million) of the total [1]. During the same year, about 75% of all PLHIV were accessing treatment. In the East and Southern African regions, 78% of PLHIV receive treatment. Subsequently, the availability of ART and effective tools for preventing, detecting, and treating opportunistic infections (OIs) is significantly reducing HIV-related deaths [2].

With the expansion of effective ART, life expectancy and quality of life of PLHIV have improved considerably. This is due to the marked advances in its potency, low adverse effect, and simplicity of the usage [3]. However, longer life expectancy of PLHIV and long-term use of combined ART have raised the concerns about increased cardiovascular risk, which are frequently grouped together and manifested as MetS [4]. Specifically, protease inhibitors (PIs) containing regimens are associated with increase in serum lipid levels and increased risk of dyslipidemia [4, 5]. On the other hand, through chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction, the virus itself can increase the risk of dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, and type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [6].

MetS is a cluster of risk factors that includes factors like raised blood sugar, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and abdominal obesity. It is a common disorder that is associated to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and T2DM in both genders [7]. Aside from the cardiovascular consequences, MetS patients are considered to be more vulnerable to a variety of conditions. These include, vascular diseases (e.g., atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and hypertension), adiposity-related disorders (e.g., sleep disordered breathing and fatty liver disease), insulin resistance conditions (e.g., T2DM or gestational diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome), atherogenic dyslipidemia, hormonal dysfunction, and chronic kidney disease [8]. Particularly, the consequences of MetS are much aggravated among PLHIV and receiving ART [6, 9–11].

A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of MetS prevalence in the global HIV-infected population revealed a high burden of MetS ranging from 16.7 to 31.3% depending on the definition used. It was also noted that the wide prevalence range reflects significant heterogeneities across and within the diagnostic criteria [12]. Additionally, MetS was reported in 21.5% of PLHIV in Sub-Saharan African countries [13].

In Ethiopia, different primary studies have reported a prevalence of MetS among PLHIV ranging from 16.8 to 43.8% based on various criteria [14–23]. Despite the fact that a number of primary studies have been conducted to assess the prevalence of MetS, no systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) has been conducted to synthesize this evidence in order to better understand the disease’s occurrence at the national level. Also, pooling the prevalence of MetS among PLHIV will enable to overcome the existing discrepancies and will support in developing of preventive and management strategies for healthcare services. Therefore, this SRMA was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of MetS among PLHIV in Ethiopia.

Methods

Protocol registration

The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). This study’s protocol can be accessed via a web address (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/#myprospero). The protocol registration number is CRD42023403786.

Search strategy

To conduct this SRMA different electronic databases such as PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Sciences, World cat, DOAJ, and Hinari were systematically searched. Also, other sources such as Google Scholar, GOOGLE, journal homepages, institutional repositories, and bibliographies were searched to retrieve eligible studies. The search terms were used as keywords and MeSH terms both individually and in conjunction with the “OR” and “AND” Boolean operators. Consequently, “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome“[Mesh] OR HIV/AIDS[tiab] OR “HIV“[Mesh] OR “HIV positive“[tiab] OR “people live with HIV“[tiab] AND (“Metabolic Syndrome“[Mesh] OR “Metabolic syndrome“[tiab] OR “cardiometabolic syndrome“[tiab] OR “Metabolic Diseases“[Mesh] AND Ethiopia were used. The EndNote X7 software was used to manage the search results. Moreover, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was used to design and report the findings of this study [24].

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

This SRMA included observational studies conducted in Ethiopia among adult PLHIV aged ≥ 18 years and accessible before September 17, 2022. Furthermore, only original full-text articles and studies written in English language were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that did not report prevalence of MetS, measured different outcomes, and did not include IDF or NCEP/ATP III criteria were excluded.

Outcome measurement

The outcome variable in this study was MetS in PLHIV, which was defined using NCEP-ATP III or IDF criteria.

NCEP-ATP III definition

Any three of the following five criteria (no absolutely required criterion) [8, 25].

IDF definition

Central obesity (waist circumferences of 94 cm for men and 80 cm for women) combined with two of the four criteria listed below [8, 25].

Criteria

Obesity: Waist circumference of > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women.

Hyperglycemia: Fasting glucose > 100 mg/dl or pharmacologic treatment.

Dyslipidemia: Triglyceride (TG) > 150 mg/dl or pharmacologic treatment.

Dyslipidemia (second, separate criteria): high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C): <40 mg/dl for males and < 50 mg/dl for females or pharmacologic treatment.

Hypertension: systolic blood pressure > 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure > 85 mmHg or pharmacologic treatment.

Data extraction

The data from each study were extracted by two independent authors (DG and HD) with a customized format in Microsoft Excel sheet. The disagreements between the two independent authors were resolved by the other authors. The extracted data included; Author names, year of publication, sample size, study design, region, and settings in which the studies were conducted.

Quality and risk of bias assessment in individual studies

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for cross-sectional studies [26] was used to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias (in design, conduct, and analysis) of included studies (supporting file 1). The tool was used to evaluate the inclusion criteria, measurement of outcome variables, confounding adjustment, and statistical analysis appropriateness. The quality of the extracted studies was evaluated by all authors who participated in data extraction.

Data analysis and synthesis

The extracted data were exported to STATA-14 for analysis. The pooled prevalence of MetS was determined with a random effect model as there was substantial heterogeneity. The heterogeneity among the included studies was checked by forest plot, Cochran’s Q (χ2 test), I2 test, and p-value. The heterogeneity was considered as low, moderate or high when I2 test statistics results were 25%, 50%, and 75% respectively [27]. Forest plots were also used to visualize the presence of heterogeneity. Sub-group analysis and meta-regression were also performed to identify the source of heterogeneity. Publication bias was checked using funnel plot of symmetry. Further, the statistical significance of publication bias was checked using Egger and Begg tests [28]. A p-value less than 0.05 was used to declare the presence of publication bias. Sensitivity analysis using a random effects model was computed to assess the influence of a single study on the overall meta-analysis estimate.

Results

Search results

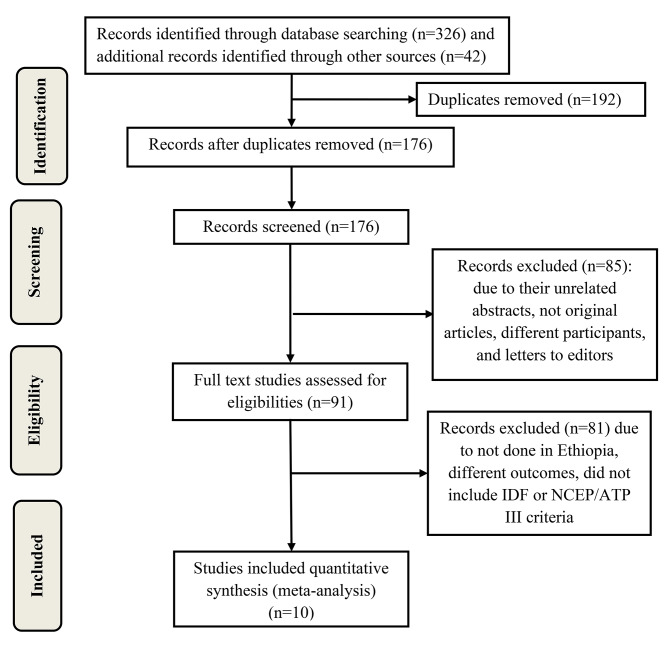

Initially, 366 studies were retrieved by different search techniques. One hundred and ninety-two studies were excluded because of duplication. Among the remaining 176 studies, 85 were excluded due to their unrelated abstracts, not original articles, different participants, and letters to editors. Other 81 studies were also excluded because they were not done in Ethiopia, had different outcomes, and did not include IDF or NCEP/ATP III criteria. Finally, 10 studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in the final SRMA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing the selection process of studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Study characteristics

This SRMA comprised 10 studies done in Ethiopia with a total of 3,751 subjects. Of the total study subjects, female patients were 2,380 (63.5%). Regarding the study regions, four studies were conducted in SNNPR [14–17], two studies were in Oromia region [18, 19], two studies were in Addis Ababa [20, 21], one study was in Amhara region [22], and one study was in Harari region [23]. Cross-sectional study designs were used in all included studies and all of them were published articles. Furthermore, all studies were published between 2012 and 2022, with sample sizes ranging from 185 to 633, and included both sexes as study participants. The prevalence of MetS was assessed using the NCEP/ATPIII and IDF criteria. Accordingly, eight studies [16–21, 23] used NCEP/ATPIII, six studies [14, 16–18, 20, 22] used IDF, and four studies used both tools [15–18, 20] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author (year) | Region | Study setting | Study design | Sample size | Sampling technique | Sex of the participants | MetS. % (NCEP-ATP III) | MetS % (IDF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woldu et al. (2022) (20) | Addis Ababa | Zewditu memorial hospital | Cross-sectional | 288 | Probability | Both men and women | 28.5 | 43.8 |

| Woldeyes et al. (2022) (21) | Addis Ababa | SPHMMC | Cross-sectional | 275 | Probability | Both men and women | 22.9 | - |

| Tesfaye et al. (2014) (17) | SNNPR | Hawassa Univ. Ref. Hospital | Cross-sectional | 374 | Probability | Both men and women | 16.8 | 23.8 |

| Hirigo et al. (2016) (16) | SNNPR | Hawassa Univ. Ref. Hospital | Cross-sectional | 185 | Probability | Both men and women | 17.8 | 24.3 |

| Gebrie (2020) (22) | Amhara | Debre M. /fel. hiw Hospital | Cross-sectional | 407 | Probability | Both men and women | - | 24.6 |

| Bune et al. (2020) (14) | SNNPR | Gedeo zone PH facilities | Cross-sectional | 633 | Non-probability | Both men and women | - | 42.5 |

| Bosho et al. (2018) (18) | Oromia | Jimma PH facilities | Cross-sectional | 268 | Probability | Both men and women | 23.5 | 20.5 |

| Berhane et al. (2012) (19) | Oromia | Jimma univ. spec. hosp. | Cross-sectional | 313 | Non-probability | Both men and women | 21.1 | - |

| Ataro et al. (2020) (23) | Harari | Jugal Hospital | Cross-sectional | 375 | Non-probability | Both men and women | 22.1 | - |

| Bune et al. (2020) (15) | SNNPR | Gedeo zone PH facilities | Cross-sectional | 633 | Non-probability | Both men and women | 22.0 | - |

NCEP-ATP III = National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III; IDF = International Diabetes Federation; JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute; SNNPR = Southern Nation and Nationalities People Region; SPHMMC = Saint Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College

Components of metabolic syndrome

The prevalence of the individual components of MetS varied significantly between studies in the Ethiopian PLHIV. The overall existences of the components were; 47.28% (95%CI: 33.18, 61.38) for low HDL-C, 39.02% (95%CI: 36.07, 41.98) for Elevated triglyceride, 36.36% (95% CI: 23.76, 48.96) for central obesity, 31.78% (95%CI: 17.61, 45.95) for high blood pressure, and 31.39% (95% CI: 22.79, 39.99) for hyperglycemia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pooled estimates of MetS components

| Author (year) | Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure | Hyperglycemia | Low HDL-C | Central obesity | Elevated triglyceride | |

| Woldeyes et al. (2022) (21) | 28.36 | 42.18 | 12.36 | 30.91 | 43.64 |

| Woldu et al. (2022) (20) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tesfaye et al. (2014) (17) | 19.25 | 27.54 | 66.31 | 50.80 | 41.18 |

| Hirigo et al. (2016) (16) | 9.73 | 31.35 | 70.27 | 51.35 | 44.86 |

| Gebrie (2020) (22) | - | - | - | 41.28 | - |

| Bune et al. (2020) (14) | 55.61 | 56.24 | 34.28 | 40.76 | 37.12 |

| Bosho et al. (2018) (18) | 38.43 | 17.16 | 49.25 | 18.66 | 29.85 |

| Berhane et al. (2012) (19) | 35.14 | 24.92 | 47.60 | 6.07 | 38.98 |

| Ataro et al. (2020) (23) | 10.93 | 25.07 | 64.53 | 59.2 | 41.87 |

| Bune et al. (2020) (15) | 56.87 | 26.38 | 34.28 | 28.91 | 36.97 |

| Total pooled estimates (95% CI) | 31.78 (17.61, 45.95) | 31.39 (22.79, 39.99) | 47.28 (33.18, 61.38) | 36.36 (23.76, 48.96) | 39.02 (36.07, 41.98) |

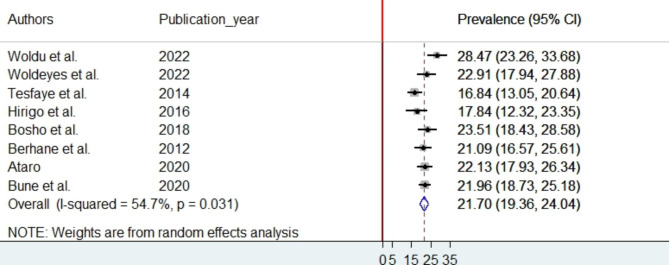

Pooled prevalence of metabolic syndrome using NCEP/ATP III

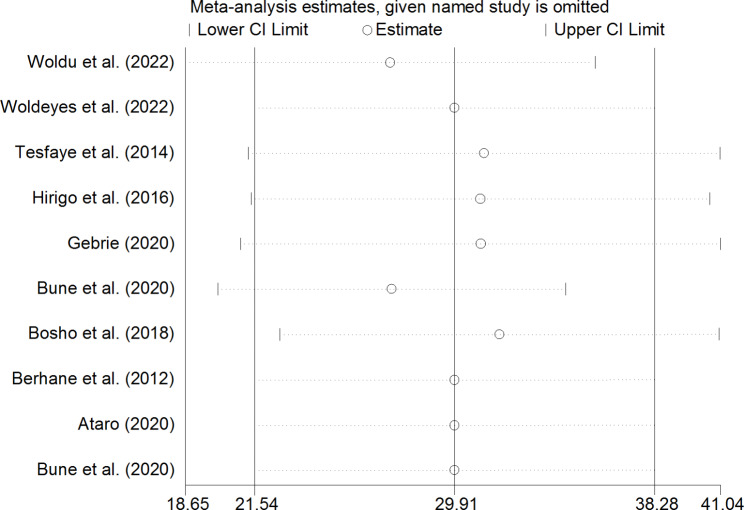

The random-effects model was used because considerable heterogeneity was observed across the studies. The pooled prevalence of MetS among PLHIV in Ethiopia is 21.7% (95% CI:19.36–24.04) using NCEP/ATP III (Fig. 2) and 29.91% (95%CI: 21.54–38.28) using IDF criteria (Fig. 3). To identify the potential source of heterogeneity across studies, subgroup analysis based on region and sampling technique was considered. However, the subgroup analysis result indicated that the source of heterogeneity was not due to region and sampling technique differences. The lowest and highest prevalence of MetS were 19.14% (95%CI: 15.63–22.64) and 25.6% (95%CI: 20.18–31.08) at SNNPR and Addis Ababa respectively based on NCEP/ATP III criteria (Supporting file 2). In addition to the subgroup analysis, meta-regression was performed, considering the year of publication and the sample size of the studies. Accordingly, the meta-regression results revealed that heterogeneity in the prevalence of MetS was unrelated to sample size variation (coefficient = -0.0032356, p-value = 0.715) or publication year (coefficient = 0.6811984, p-value = 0.079) based on NCEP/ATP III criteria.

Fig. 2.

The forest plot of pooled prevalence of MetS according to NCEP-ATP III criteria

Fig. 3.

The forest plot of pooled prevalence of MetS according to IDF criteria

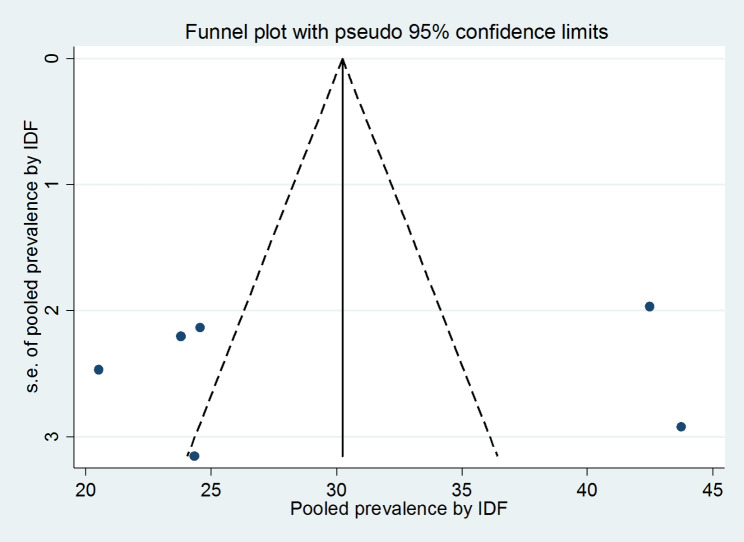

Publication bias

The presence of publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger, and Begg statistical tests at 5% significant level. There was no statistical evidence of publication bias in both NCEP-ATP III and IDF pooled estimates. For the NCEP-ATP III pooled estimate, the funnel plot was almost symmetry (Fig. 4), the Begg and Egger tests were statistically non-significant (p-value = 0.266 and p-value = 0.482) respectively. Also, For the IDF pooled estimate, the funnel plot was almost symmetry (Fig. 5), the Begg and Egger tests were statistically non-significant (p-value = 0.707 and p-value = 0.802) respectively.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plots for publication bias based on NCEP-ATP III criteria

Fig. 5.

Funnel plots for publication bias based on IDF criteria

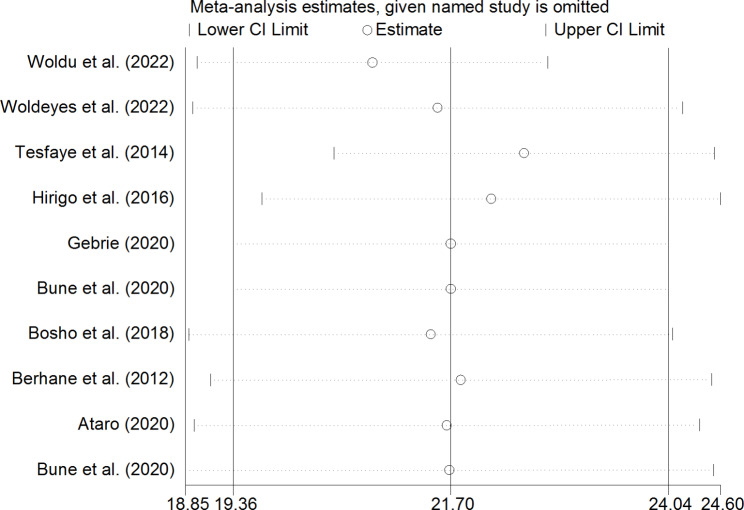

Sensitivity analysis

To identify the effect of single study on overall meta-analysis estimate, sensitivity analysis using a random effects model was computed. The analysis found no strong evidence for influence of single study in both NCEP-ATP III (Fig. 6) and IDF (Fig. 7) pooled estimates.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis for single study influence of pooled estimate based on NCEP-ATP III criteria

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis for single study influence of pooled estimate based on IDF criteria

Discussion

MetS is now becoming a problem for PLHIV [9]. This SRMA disclosed the pooled prevalence of MetS in Ethiopia. Thus, the pooled prevalence of MetS among PLHIV in Ethiopia is 21.7% (95% CI:19.36–24.04) using NCEP/ATP III and 29.91% (95% CI: 21.54–38.28) using IDF criteria. As a result, even though the pooled point prevalence of the MetS is higher with NCEP/ATP III criteria than with IDF criteria, their confidence intervals overlap, indicating the comparability of the criteria. The NCEP/ATP III criteria-based pooled prevalence in this study was consistent with the reports from global SRMA (24.6%) [12], the recent systematic review (20.6%) [29], and the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries (19.9%) [13]. Similarly, the IDF criteria-based pooled prevalence in this study was also comparable with the reports from the sub-Saharan Africa countries (25.7%) [13]. This might be due to use of comparable case definition for MetS. Furthermore, despite an inconsistent depiction of studies from around the world, the prevalence of MetS was roughly similar within and across major regions, including continents and intra-country locations, regardless of the definition criteria used [12].

This finding is also consistent with other SRMA studies conducted in Ethiopia on a diverse range of populations. The SRMA in 2021 found that 30% of people had MetS, with the highest burden among diabetics (56%) and hypertensive patients (44%) [30]. Furthermore, the 2020 SRMA found that the pooled prevalence of MetS in Ethiopia was 34.89% using NCEP/ATP III criteria and 27.92% using IDF criteria [31]. This could be because PLHIV were also a significant part of previous studies, similar diagnosing criteria were used, and the settings were also comparable. Furthermore, the SSA study indicated the need for immediate prevention and management programs to halt the progression of MetS, regardless of HIV status [13].

Low HDL-C was the most common individual component of MetS in the current SRMA which was similar to reports from the SSA countries [13] and Kenya [32]. This suggests that low-HDL continues to be a major precursor for MetS, implying that timely intervention is required to prevent MetS progression. The other MetS component found prevalent in this study was high triglyceride levels. This finding is in agreement with the study from Italy [33]. This is caused not only by the virus, but also by the ART drugs used to treat the infection. According to the most recent large survey, more PLHIV with MetS than those without MetS had ever been exposed to PIs [9]. As a result, a detailed patient’s medical assessment is essential for prioritizing risk mitigation and primary care prevention services.

Furthermore, this SRMA confirms that other major MetS components, such as central obesity, high blood pressure, and hyperglycemia, are predominant among Ethiopian PLHIV. This is evidenced by the previously conducted review article [34]. To prevent CVDs, current HIV recommendations encourage the use of standard lifestyle interventions such as weight loss, exercise, smoking cessation, and eventually pharmacological interventions such as antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy, as well as treatment of glucose metabolism alterations [35].

The strengths of this SRMA include a complete literature search in the various relevant database, proper screening of eligible studies, and strong assessment of quality to rule out the quality bias. The limitation was; the meta-analysis result should be interpreted cautiously due to heterogeneity among studies.

Conclusion

MetS was common among PLHIV in Ethiopia. Therefore, optimizing regular screening for MetS components and promoting a healthy lifestyle is suggested for PLHIV. Furthermore, more study is contributory to identify the barriers to implementing planned interventions and meeting recommended treatment goals. Moreover, a context-specific tool for measuring MetS among PLHIV should be developed to improve the replicability of the studies in Ethiopia.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

DG conceived the idea, developed the research question and inclusion criteria. DG, HD, LA, ES, MT, MA, and BT outlined the search strategy and involved in analysis and narration, contributed to drafting and editing of review during the process. All authors critically revise the manuscript for important rational content and approved the final version of the review for publication.

Funding

There was no specific funding was received for this review.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Derara Girma, Email: deraragirma24@gmail.com.

Hiwot Dejene, Email: hiwotdejene74@gmail.com.

Leta Adugna Geleta, Email: letaadugna72@gmail.com.

Erean Shigign Malka, Email: erean2025@gmail.com.

Mengistu Tesema, Email: mengstutesema@gmail.com.

Mukemil Awol, Email: mukemilawol2006@gmail.com.

Befekadu Tesfaye Oyato, Email: befekadutes2016@gmail.com.

References

- 1.WHO. HIV 2022 [14 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids.

- 2.IN DANGER. : UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS;, 2022.

- 3.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort C Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nduka C, Sarki A, Uthman O, Stranges S. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on serum lipoprotein levels and dyslipidemias: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:307–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meena DS, Rai M, Singh SK, Tapadar J, Kumar D. Metabolic changes in the patients on second-line highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a prospective cohort study from north India. J family Med Prim care. 2020;9(3):1550–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1208_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diggins CE, Russo SC, Lo J. Metabolic consequences of antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022;19(2):141–53. doi: 10.1007/s11904-022-00600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112(20):3066–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sperling LS, Mechanick JI, Neeland IJ, Herrick CJ, Despres JP, Ndumele CE, et al. The CardioMetabolic Health Alliance: Working toward a New Care Model for the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(9):1050–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ang LW, Ng OT, Boudville IC, Leo YS, Wong CS. An observational study of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in treatment-experienced people living with HIV in Singapore. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han WM, Law MG, Choi JY, Ditangco R, Kumarasamy N, Chaiwarith R, et al. Weight changes, metabolic syndrome and all-cause mortality among asian adults living with HIV. HIV Med. 2022;23(3):274–86. doi: 10.1111/hiv.13211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu WL, Lee YT, Sheu GT. Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence and Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in HIV-Positive Men with and without Antiretroviral Therapy.Medicina. 2021;57(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Nguyen KA, Peer N, Mills EJ, Kengne AP. A Meta-analysis of the metabolic syndrome prevalence in the Global HIV-Infected Population. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0150970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todowede OO, Mianda SZ, Sartorius B. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among HIV-positive and HIV-negative populations in sub-saharan Africa-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst reviews. 2019;8(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0927-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bune GT, Yalew AW, Kumie A. The extents of metabolic syndrome among antiretroviral therapy exposed and ART naïve adult HIV patients in the Gedeo-zone, Southern-Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Archives of Public Health. 2020;78(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bune GT, Yalew AW, Kumie A. The global magnitude of metabolic syndrome among antiretroviral therapy (ART) exposed and ART-naive adult HIV-infected patients in gedio-zone, southern Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study, using the adult treatment panel III criteria. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(5):2833–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirigo AT, Tesfaye DY. Influences of gender in metabolic syndrome and its components among people living with HIV virus using antiretroviral treatment in Hawassa, southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1953-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tesfaye DY, Kinde S, Medhin G, Megerssa YC, Tadewos A, Tadesse E, et al. Burden of metabolic syndrome among HIV-infected patients in Southern Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2014;8(2):102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosho DD, Dube L, Mega TA, Adare DA, Tesfaye MG, Eshetie TC. Prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWHIV) Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10:10. doi: 10.1186/s13098-018-0312-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berhane T, Yami A, Alemseged F, Yemane T, Hamza L, Kassim M, et al. Prevalence of lipodystrophy and metabolic syndrome among HIV positive individuals on highly active anti-retroviral treatment in Jimma, South West Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woldu M, Minzi O, Shibeshi W, Shewaamare A, Engidawork E. Biomarkers and prevalence of Cardiometabolic Syndrome among People living with HIV/AIDS, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Hospital-Based study. Clin Med Insights: Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022;15:11795514221078029. doi: 10.1177/11795514221078029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woldeyes E, Fisseha H, Mulatu HA, Ephrem A, Benti H, Alem MW, et al. Prevalence of Clinical Cardiovascular Disease Risk factors among HIV infected patients on anti-retroviral treatment in a Tertiary Hospital in Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2022;14:297–309. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S362459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebrie A. The burden of metabolic syndrome in patients living with HIV/AIDS receiving care at referral hospitals of Northwest Ethiopia: a hospital-based cross-sectional study, 2019. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):1551–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ataro Z, Ashenafi W. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among adult HIV positive people on antiretroviral therapy in Jugal hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. East Afr J Health Biomedical Sci. 2020;4(1):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet medicine: J Br Diabet Association. 2006;23(5):469–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moola SMZ, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu P-F. In: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Aromataris EMZ, editor. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woldu M, Minzi O, Engidawork E. Prevalence of cardiometabolic syndrome in HIV-infected persons: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19(2):1671–83. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00552-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jemere T, Kefale B. Metabolic syndrome and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2021;20(1):1021–31. doi: 10.1007/s40200-021-00815-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambachew S, Endalamaw A, Worede A, Tegegne Y, Melku M, Biadgo B. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopian Population: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Obes. 2020;2020:2701309. doi: 10.1155/2020/2701309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masyuko SJ, Page ST, Kinuthia J, Osoti AO, Polyak SJ, Otieno FC, et al. Metabolic syndrome and 10-year cardiovascular risk among HIV-positive and HIV-negative adults: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2020;99(27):e20845. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calza L, Colangeli V, Magistrelli E, Rossi N, Del Rosselli E, Bussini L, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients naive to antiretroviral therapy or receiving a first-line treatment. HIV Clin Trial. 2017;18(3):110–7. doi: 10.1080/15284336.2017.1311502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin-Iguacel R, Negredo E, Peck R, Friis-Moller N. Hypertension is a key feature of the metabolic syndrome in subjects aging with HIV. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18(6):46. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0656-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Group ISS, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.