Abstract

The inaugural Women in Behavior Analysis Conference (WIBA) was hosted in 2017 to highlight the accomplishments of women in the field of behavior analysis, provide opportunities for early career behavior analysts to obtain mentorship, and encourage meaningful discourse about gender issues in the field. In 2021, WIBA created the Hall of Fame to identify and honor outstanding women who have contributed to the field. Four stellar and important women were inducted into the inaugural class: Eve Segal, Bea Barrett, Martha Bernal, and Judith Favell. This article provides an overview of the structure and function of the hall of fame as well as the individual accomplishments, accolades, and impacts of these women as described in the Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Each year a newly selected group of women will be inducted, and their career will be highlighted in an article in Behavior Analysis in Practice.

Keywords: Accomplishment, Behavior analysis, Women, Eve Segal, Bea Barrett, Martha Bernal, Judith Favell

The chair of the committee is listed as the first author followed by the other presenters in the order in which the inductees were presented. The last two authors are employees of Women in Behavior Analysis. However, all authors of this manuscript contributed equally to the final product.

Sundberg et al. (2019) described the establishment of the Women in Behavior Analysis (WIBA) Conference 2017. The mission of the conference and the organization is “to empower, celebrate, and mentor women behavior analysts; highlight their contributions to the field; and to engage all genders in meaningful discourse on gender equality for the promotion of behavior analysis and professional growth of future generations” (www.wiba.com). The WIBA organization and conference provide a professional association for women in behavior analysis and an annual opportunity to network with other women in an environment that celebrates women and their contributions.

Sundberg et al. (2019) answered the question “Why WIBA?” by elucidating the political climate shifts (e.g., a rise in feminism) in the latter part of that decade (i.e., 2010–2020) along with a realization that the perception that women had actually achieved full equality was naïve. Discrepancies in pay and high-level opportunities in the field across genders, as well as the relative lack of awareness regarding the accomplishments and impact of early women in the field existed in the formative years of our profession and still exist today (Li et al., 2018; Nosik et al., 2018; Zahidi et al., 2018). As of 2016, 88% of certificants in behavior analysis were female, but women were still underrepresented in the categories of professional recognition (e.g., 17.2% of later career awardees and 35% of earlier career awardees) and invited presentations at regional and national level conferences (e.g., 27.9% of invited presentations; see Nosik et al., 2018 for additional details). Li et al. (2018) found that across several behavioral journals, women represented 37.7% of editors and 42.7% of first authors. All of these numbers actually represent significant increases compared to prior decades, but it is clear that there is still underrepresentation.

Sundberg et al. (2019) described the intention “to sustain this effort through slow growth, maintaining an active Advisory Committee, gathering and implementing extensive feedback from [conference] attendees, attracting a diverse audience, and collecting data to correlate with cultural outcomes” (p. 814). One of WIBA’s proudest accomplishments is creating an environment where the work of female behavior analysts who may not have received their fair recognition could be highlighted. This effort began with a presentation at WIBA in 2018 by Edward Morris who highlighted the accomplishments and professional struggles of some of the field’s founding mothers (Morris, 2018). Many in the audience that day had never heard of women such as Eve Segal and Ellen Reese and had no idea what an influence these women had. Segal, a student of B. F. Skinner and K. MacCorquodale, presented her story of struggles being a woman in science in an invited address to the American Psychological Association (APA) (Gilbert, 2017). Reese holds a place on APA’s 100 Most Important Women in Psychology (Morris, 2003). If these names are unfamiliar to you, as they were to many of our attendees that year, you are about to become educated about the influences of amazing and powerful women in your own field. “These women were there, but mainly ignored” at that time (Donald Baer, quoted in Wesolowski, 2002, p. 146). WIBA’s goal is to ensure that their contributions are no longer ignored and that these women take their rightful place in the history of the pioneers in behavior analysis.

At a subsequent conference, one member of the Advisory Committee, Linda LeBlanc (first author), suggested that there may be value to creating a Hall of Fame specifically to honor the early female founders and contributors to our field in a way that only other women might do. In 2021, WIBA took the next step in educating the current generations of behavior analysts about the tremendous accomplishments of some of the female pioneers in our field by establishing the WIBA Hall of Fame, and the inaugural class of inductees were selected and honored at the 2021 WIBA conference. The purpose of this article is to describe the creation and ongoing function of the WIBA Hall of Fame and to highlight the accomplishments of the first class of women who were pioneers in behavior analysis for those who were not in attendance at the conference. The 2022 inductees to the WIBA Hall of Fame will be honored in the June 2023 issue of Behavior Analysis in Practice, and the 2023 inductees to the WIBA Hall of Fame will be honored in the September 2023 issue of Behavior Analysis in Practice. Inductees to the WIBA Hall of Fame will be subsequently honored each year in the September issue of Behavior Analysis in Practice. Readers are encouraged to look for these special articles each year. [Editor’s Note: Behavior Analysis in Practice is pleased to serve as an outlet for highlighting the accomplishments of notable women in the field of behavior analysis and to play a role in gender equity within the field.]

Creation of the WIBA Hall of Fame

The WIBA Hall of Fame was created with the mission to honor the accomplishments of female pioneers in the field of behavior analysis and create a historic record to educate behavior analysts on their contributions. The criteria for induction to the WIBA Hall of Fame are women who: (1) have 30 or more years of experience in the field of behavior analysis; (2) are retired or semi-retired; (3) are an exemplary role model for the next generation of behavior analysts; (4) have substantial accomplishments in the form of awards, scholarly contributions, leadership positions, and teaching and mentoring of behavior analysts; and (5) have created opportunities, space, and resources for female contemporaries and future generations of women to succeed. In addition, the Committee acknowledges and places particular emphasis on educating members of the behavior analytic community about the significant adversity faced by many of these women, as well as the unique value of their accomplishments in the context of the significant barriers that they faced. There are many women who currently meet these criteria or will upon their exit from the field at some future date. Thus, the inaugural class is intended to be followed by a new class each year for the foreseeable future.

The selection committee for the WIBA Hall of Fame is and will remain an all-women selection committee, because the purpose of this effort is for women to have the decision-making power to honor and celebrate other women in behavior analysis. However, all are welcome to attend the conference and join in the celebration. The selection committee is appointed by the WIBA Hall of Fame Committee Chair, who is currently Linda LeBlanc (first author). The committee consists of at least one other member of the WIBA Advisory Board (currently Denise Ross Page, fifth author) and at least two other qualified members who do not serve on the Advisory Board (currently Carol Pilgrim, fourth author, and Chata Dickson, third author). The number of members on the committee matches the number of inductees so that each committee member can take on the task of researching the life of one inductee and preparing the induction presentation for the conference. The WIBA staff provide the operational support, organizing and maintaining the record of meetings and arranging the induction ceremony and reception.

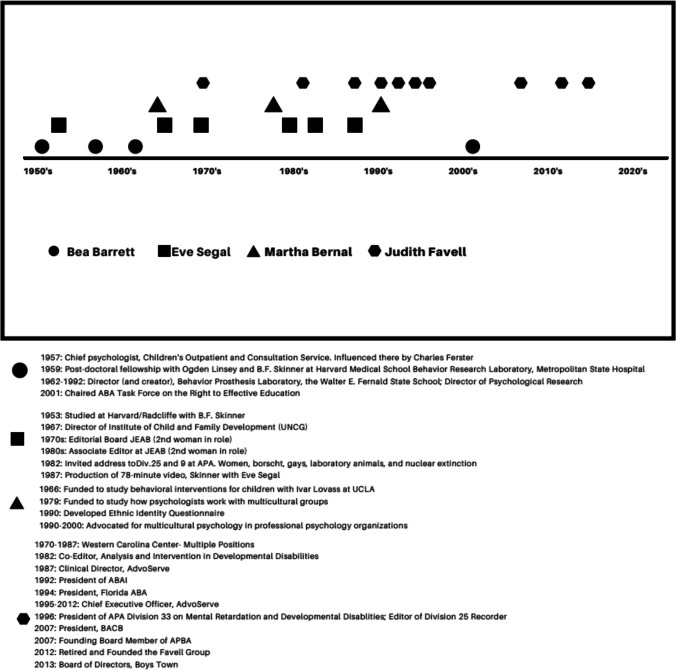

In general, five or six individuals will be inducted to the WIBA Hall of Fame each year. However, the inaugural induction also focused on describing the WIBA Hall of Fame; thus, only four women were inducted that year. Figure 1 provides a timeline sampling the stellar accomplishments and milestones of these four women. The committee considered many candidates and selected four, paying particular attention to reflecting and honoring the diversity of our field and to representing a wide range with respect to timing of career. The intention is to continue selecting inductees that represent diverse groups and to honor their impact, even if (and perhaps particularly when) some of these women were not appropriately acknowledged or considered prominent at the time they were active in the field. Memorabilia such as photos, articles and research artifacts will be collected as a living history display that can be explored at the WIBA conference each year. Some of these artifacts are also contained in this article in an effort to maintain a public and enduring legacy to the contributions of these prominent women.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of important events for the 2021 inductees to the women in behavior analysis hall of fame

Accomplishments and Contributions of the 2021 Inductees to the WIBA Hall of Fame

Evalyn Finn Segal

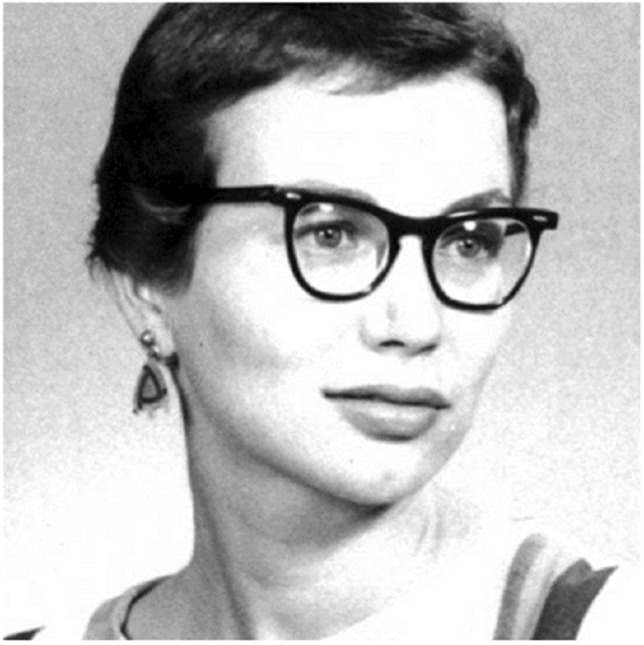

Dr. Evalyn F. Segal (1932–2017) (see Fig. 2) was an early contributor to the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, at a time when only a handful of women were authoring articles in the journal. Dr. Segal was the second woman to serve on the editorial board, and later, the second to serve as an associate editor (Gilbert, 2017). Her major professional contributions centered around three themes. The first was the experimental analysis of behavior, with a focus on schedules of reinforcement, and a process called induction. She worked to solve the puzzle of the first response—behavior must occur before it can be reinforced, but how does that initial response come to be? The second theme was verbal behavior. She was a student of B. F. Skinner’s work in verbal behavior prior to the publication of his 1957 treatise and remained an expert in and contributor to this area throughout her career. The third theme was broadly related to behavior theory, ethical behavior, and activism. In the tradition of Skinner, she discussed and deconstructed problems of human behavior in daily life and society, reflecting upon the ways in which humans treat one another under sets of metacontingencies (Segal, 1987), and she also advocated for the well-being of laboratory animals (e.g., Segal, 1982, 1989).

Fig. 2.

Evalyn Finn Segal. Photo credit: R. Gilbert who obtained the photo from University of California San Diego

She earned her first degree when she was 17 years old from the Great Books program at the University of Chicago. This degree was centered around what were considered at the time to be the most important books to Western civilization. She continued to be a veracious and broad reader throughout her career, and this can be seen in the scholarly references she made in her writing (D. A. Eckerman, personal communication, July 22, 2021).

She completed a second undergraduate degree at the University of Minnesota under the advisement of Kenneth MacCorquodale, who had been a student of Skinner’s. During this time, she read Keller and Schoenfeld (1950), and she was compelled by behaviorism and experimental analysis of behavior (Segal, 1982). Completing a doctoral degree with Skinner seemed to be a natural next step, and she was accepted as a doctoral student in Skinner’s lab—though she did this as a Radcliffe college student, because Harvard was not accepting women as students in 1953. Female students were enrolled through Harvard’s sister programs at Radcliffe College. While she was at Harvard, Segal took a class from Skinner on verbal behavior while he was putting the finishing touches on his 1957 book that provided an operant account of communication and language (D. A. Eckerman, personal communication, July 22, 2021). She was at Harvard for only one term, and she spoke about her experiences there in an address to Divisions 25 and 9 of the American Psychological Association (Segal, 1982).

Segal completed her doctoral degree with MacCorquodale back in Minnesota in 1958. Following graduate school, she learned that landing a job in academia was no small feat for a woman at that time. She was told by the institution granting her degree that they would not be ready to hire women as faculty for a few more years. She found it perplexing that an institution would train a person for a job in academia whom they would not be willing to hire (Segal, 1982). Nevertheless, Segal published more than 30 articles over the following decade. Most of these were related to behavioral induction, including schedule-induced behavior like polydipsia, which refers to a period of excessive drinking beyond what could be accounted for by other factors (Segal, 1972).

In 1960, she was hired as an assistant professor at San Diego State College. Seven years later she moved to North Carolina to serve as director of the Institute of Child and Family Development at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. This work seemed to have reignited her interest in verbal behavior (Gilbert, 2017). While she was in North Carolina, she published her most cited work, Induction and the Provenance of Operants (Segal, 1972). This article was the culmination of her work in schedule-induced behavior, and it continues to influence behavior theory and philosophy today.

In 1973, Segal returned to San Diego State University where she established and led a primate laboratory. See Fig. 3. She published another important article in 1977 in which she sought to reconcile the linguistic theories of Skinner and Chomsky (Segal, 1977). She related to Gilbert that she thought it was a pity that the two thinkers were enemies, as she put it, and that they did not speak or read one anothers’ work (Gilbert, 2017).

Fig. 3.

Eve Segal with a Primate Friend. Reprinted with permission from the publisher

In her 1982 address at APA, Segal took the opportunity to share her experiences as a student and professional and did not shy away from describing some of the hardships she encountered along the way (Segal, 1982). She acknowledged that this was quite unusual for an address at a scientific meeting, and what she shared provided important context for the experience of woman and queer people. She spoke about that semester at Harvard. She described her joy with working in the lab and learning from Skinner and Charlie Ferster. She also spoke of the tragic series of events that led to her expulsion. This began when she was raped by another student from the lab at an off-campus celebration. She described her experience as she struggled to recover from this event. Segal sought help from a psychiatrist. She shared with him about her life and spoke of challenges that came along with being a gay woman, as she described herself. The psychiatrist contacted the dean and urged him to expel her. Skinner pushed back but was unsuccessful in keeping her as a student. Their warm relationship continued and in 1987 they recorded a video interview, which continues to be available on the Internet (Segal, 1988).

In her sharing of the facts that led to her departure from Harvard, there was no bitterness; only a hope that her audience would not let something like this happen at their own universities. She said in her speech that “although nature... and data are impersonal... science is neither impersonal nor is it value-free” and argued that we need “to acknowledge and incorporate our humanity in all our scientific activities. Further, as with any human activity, science cannot escape a moral dimension” (Segal, 1982, p. 2). Evalyn Segal’s efforts did not stop with research and writing. She lived her values with the goal of effecting change. Over the years, she was engaged in activism and advocacy in favor of nuclear disarmament, women and queer people, people who worked in academia, people suffering from chronic illness, and the humane treatment of animals (Segal, 1982). In the final decades of her life, Segal shifted her attention to the visual fine arts, enjoying collaboration and community with follow artists (D. A. Eckerman, personal communication, July 22, 2021).

In her research, writing, and activism, as well as in her willingness to share her experiences, values, and hopes for the future in that 1982 address, Evalyn Segal a gave great gift to the field of behavior analysis and to those of us who see ourselves reflected in her experience and values. We are fortunate to have had Dr. Segal as an important member of our field, and we are lucky that she gave us a chance to know her, even if only a little bit.

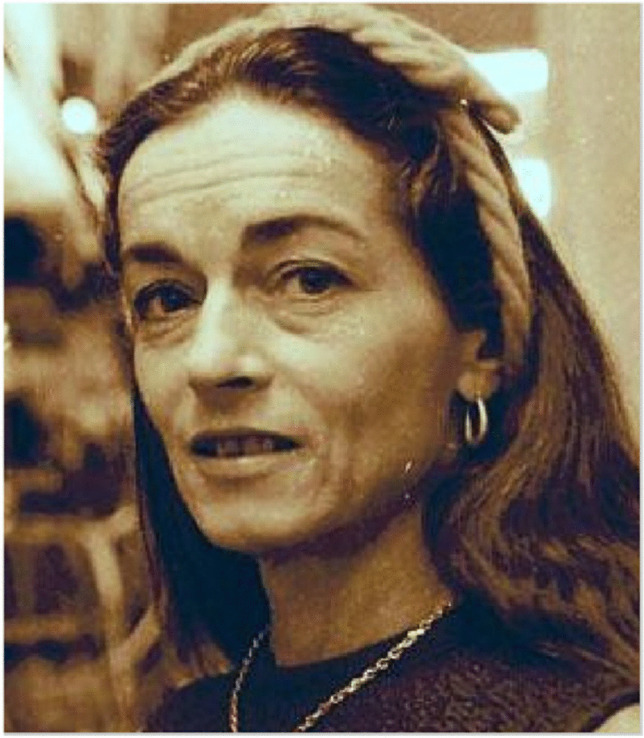

Beatrice (Bea) Helene Barrett

Dr. Beatrice Helene Barrett (1929–2003) (see Fig. 4) takes a rightful seat as a member of the inaugural class of WIBA’S Hall of Fame inductees. Even a brief review of her role in the early years of our discipline will reveal just what an iconoclast she was. In today’s parlance, we would definitely call Bea a “badass” woman. In her day, she enjoyed duking it out with the best of them, doing what it took to get this field of behavior analysis off and running, and then later staying the course.

Fig. 4.

Bea Barrett. Photograph courtesy of Carl Binder, personal collection

Although impossible to do justice in these few paragraphs, a small sampling of the pioneering arcs of her work includes the fact that Dr. Barrett was one of the very first behavior analysts to illustrate the potential of human operant laboratory work—one of the cornerstones of our field today. She conducted seminal investigations of discrimination learning under carefully controlled conditions in individuals with developmental delays, but she didn’t stop there. Her real focus was on showing how the identification of individual differences in discrimination acquisition, measured in terms of response rate, could inform clinical assessments and the design of therapeutic interventions.

Dr. Barrett was a true translational scientist, long before that was trendy, conceptualizing her laboratory and clinical work as all of a piece. This led to approaching clinical targets in terms of their functions. Bea went on to make great strides in expanding interventions for individuals with intellectual delays to include academic skills. Indeed, she established the first classroom program based completely on behavioral science in the 1960s. She was also one of the first to explore teaching nonprofessionals (e.g., parents and students) to implement behavioral procedures and thereby work towards greater generalization—all key themes in applied behavior analysis to this day.

There were numerous milestones throughout Dr. Barrett’s career, just a few of which are highlighted in her portion of the timeline. Her early training and professional experiences with standard clinical assessment were probably important establishing operations for her total embrace of response rate measures when she joined Og Lindsley and Fred Skinner as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard. Bea went on to highlight the use of rate measures in many publications, across a wide range of journals, and in her position as director of research at the Fernald State School for 30 years. Later in her life, she chaired the influential Association for Behavior Analysis Task Force on the Right to Effective Education and was invited to write an introduction for a new edition of Skinner’s Technology of Teaching. As it turned out, that intended introduction grew into a full-length book in its own right—Bea was concerned that Skinner’s technical terminology in the book made it inaccessible to many who needed most to hear its message. Her translation was published the year before her death.

Bea Barrett was beautiful and elegant, tall and slim, always tan. See Fig. 5. She is described as brilliant and kind, but not one to suffer fools lightly—and she was a woman of great passions. She was an avid open-sea sailor and by all counts cursed like one too, preferring to sail in the buff whenever possible. She loved science and the arts and her cat, Libby (short for Libido), who often accompanied Dr. Barrett to work and to conferences. Upon Bea’s death, she left legacy endowments including a laboratory research program to the University of North Texas, an extensive modern art collection to the DeCordova museum close to her home, and significant contributions to the Boston Ballet as well as several organizations devoted to conservation of wildlife and the natural environment.

Fig. 5.

Bea Barrett. Photograph courtesy of Carl Binder, personal collection

Those who had the good fortune to know Dr. Barrett personally speak compellingly of her influence. This quote from Kent Johnson (personal communication) emphasizes Bea teaching him about true units of analysis, why they matter, and how they can transform approaches in education.

My experiences with Bea occurred after I had earned my doctorate. Just when I thought I had reached a pinnacle of some sort with a Ph.D., I discovered another behavioral world that would dominate my practices going forward to the present day. Bea was a measurement expert, who taught me so much more about measurement. . . . Her distinction between “units of measurement” and “units of analysis” really helped me see the problems with so much research at the time, which plotted “units of task analysis completed” on graphs as if they were units of measurement! She was truly a remarkable person in my intellectual life—the first to show me how to focus on teaching academic skills to children and adults with developmental disabilities, and the only one I’d ever seen working with DD students in a classroom environment.

Figure 6 speaks to one of her major crusades. Each panel presents data from three groups of individuals—typical adults, typically developed 5- to 7-year-old children, and 12- to 54-year-old students from the Fernald State School, to whom she devoted so much of her life. For each group, data were collected on a number of basic academic tasks—writing numerals, naming numerals, counting tiles, and so on. Data in the panel on the left are presented as percent correct, and Bea’s key point was that if this was the only measure considered, you might conclude that the State School students were on par with the other groups, and thus well prepared for community living—deinstitutionalization being a major push at the time. The panel on the right, however, depicts the very same performances measured as rate of responding, with data from the State School students are shown in the open bars. It is clear that there were important dimensions in need of additional intervention if the State School students were to be successful in community life.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of percent correct measures to response per minute measures on academic tasks. Note. Reprinted with permission from Johnson et al. (2019)

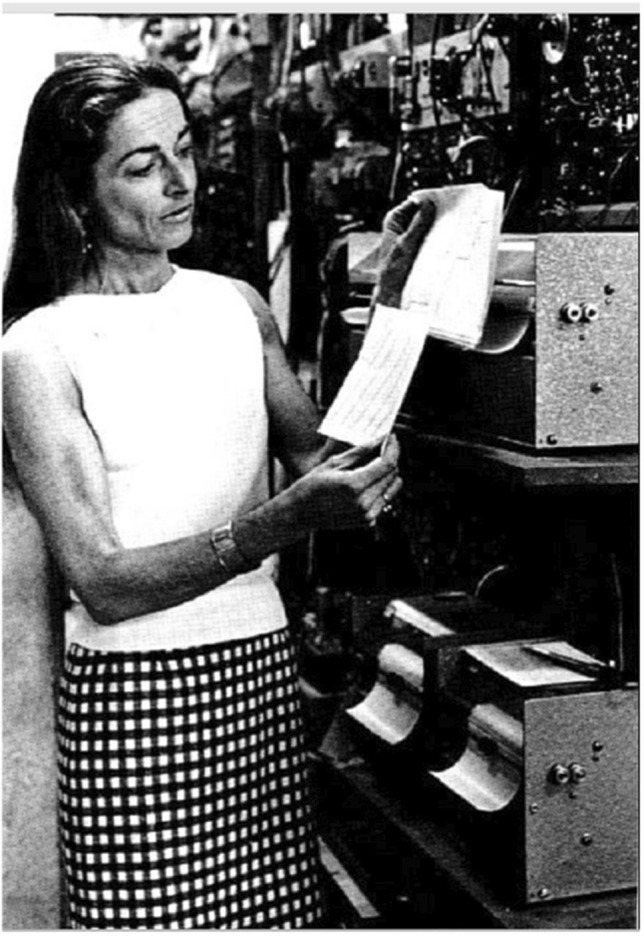

Figure 7 presents a classic image of Bea Barrett—with her prized cumulative records, which she referred to as her paper dolls due to the necessary cutting and pasting—as do these words by Carl Binder:

In the 1960s and 1970s, Bea was a rare woman in a mostly man’s world of experimental science, and she served as a role model for women throughout her career. Many colleagues in behavior analysis acknowledge her as among the most precise and elegant writers in the field. Her meticulously crafted publications remain valuable today for students, researchers, and practitioners. (Binder, 2004, p. 561)

Fig. 7.

Bea Barrett examining a cumulative record. Photograph courtesy of Carl Binder, personal collection

One must wonder—how many behavior analysts will have their publications still being recommended 50 to 60 years from now?

As a fitting wrap-up for her induction into the WIBA Hall of Fame, consider this dedication to Dr. Barrett from Hank Pennypacker and Og Lindsley in their classic celeration chart book:

“We lovingly dedicate this edition to Beatrice H. Barrett, whose grasp of the crucial role played by measurement in both the science and technology of behavior is unequaled” (Pennypacker et al., 2003, preface). In the eyes of those two, there could be no higher praise. In fact, to a person, every individual contacted in researching Dr. Barrett’s contributions made the same observation—that behavior analysis would be better off today if more had heeded her guidance. Now that’s a legacy. May this WIBA Hall of Fame induction bring renewed attention to her wisdom and insights. To Bea!

Martha Bernal

Dr. Martha Bernal (1931–2001) (see Fig. 8) was born to Mexican American parents who had immigrated to Texas from Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Martha, who was raised in a loving, close-knit Mexican American community, found herself at odds with the traditional roles for women held by her family because she wanted to go to college instead of marrying and having children after high school. In her autobiography she wrote,

Upon finishing high school, I literally had to conduct battle with my father about going to college. My father’s view was that, because we were women, we would be getting married, and a college education would be a waste. I went to work for a year after high school, saved my salary, and announced I would be going to college. Eventually, my father gave in and assisted me financially.” (Bernal, 1988, pp. 265–266)

Fig. 8.

Martha Bernal.Photo credit: Salud America! Permission to reprint obtained from publisher

Martha attended the University of Texas at El Paso for her undergraduate program, obtained her master’s degree in special education at Syracuse University, and then began her doctoral degree in clinical psychology at Indiana University. While at Indiana University, she encountered significant financial, gender, and racial barriers to her doctoral education. She wrote, “There is much to tell about the racism and sexism that pervaded these years of graduate school. I won’t give details of how some professors chased my fellow female students and me around their labs and offices” (Bernal, 1988, p. 267). Although tempted to quit because of gender bias, she followed the advice of mentors to continue, and upon the completion of her doctoral degree in 1962, Martha Bernal became the first Hispanic woman and the first American of Mexican descent to obtain a doctoral degree in clinical psychology in the United States. It was after graduate school that Martha experienced two major transformations that would become the foundation of her phenomenal contributions to psychology.

The first transformation was a shift from traditional psychotherapy to behavior analysis in her practice as a clinical psychologist. She studied the research of behavior analysts Charles Ferster, Marian DeMeyer, Ogden Lindsley, and Ivar Lovaas, and observed the effectiveness of their work with children and adults. She subsequently used behavior analysis to develop parent-training interventions that helped children with behavioral challenges, and she became nationally known for the use of effective measurement to assess children’s behavior. In her autobiography, she stated that:

My work, and that of other pioneers in this field, eventually led to the adoption of a very different theory about human problems, namely, that children who had such problems were not internally ill or damaged but had learned their maladaptive behaviors. They could unlearn them and could be taught a more adaptive behavioral repertoire. (Bernal, 1988, p. 270)

The second major transformation that she experienced was a deeper understanding of racial bias in psychology. See Fig. 9. In 1979, during a sabbatical from her faculty position at the University of Denver, Martha focused her attention on a long-held interest: the mental health of Hispanic children and the role of Hispanic psychologists. She studied the role of race in sociology, psychology, political science, and history for Mexican Americans and other American minorities. In her autobiography, she described the transformation that she experienced:

Now I realized that my own life had been deeply and personally affected by racist America. My own profession restricted ethnic minorities’ access to graduate training and to service as professors on our faculties. It also graduated White behavioral scientists and practitioners who had been raised in a racist society, and many of these professionals devalued any but their own culture and language. (Bernal, 1988, p. 272)

Fig. 9.

Martha Bernal. Photo credit: Salud America! Permission to reprint obtained from publisher

This shift in her focus resulted in significant advocacy for racial equity in the practice, training, and service of psychology. See Fig. 10. Dr. Bernal studied the identity development of Mexican American children (Ballie, 2002) and developed measurement tools to assess behavioral problems among children as well as the Ethnic Identity Questionnaire (Bernal et al., 1990). She gained national recognition for demonstrating the application of behavioral interventions to behavior problems for children and for her advocacy for multicultural psychology (Vasquez, 2010). She also provided significant leadership to organizations that supported psychologists of color including the Board of Ethnic Minority Affairs (BEMA), the National Latino/a Psychological Association, and APA’s Commission on Ethnic, Minority, Recruitment, Retention, and Training (CEMRRAT) (Vasquez, 2010). She was recognized by the Latino Psychology Conference for her contributions to Latino psychologists and by the American Psychological Association with the Distinguished Life Achievement Award and Distinguished Contribution to Psychology in the Public Interest Award (Ballie, 2002).

Fig. 10.

Martha Bernal. Photo credit: Vasquez & Lopez, 2002. Permission to reprint obtained from publisher

Although Dr. Bernal is most widely known for her contributions to the treatment of children and multicultural psychology, she is also known for another major contribution: investing in the careers of Hispanic psychologists. Former APA president Dr. Melba Vasquez, described her experiences as Dr. Bernal’s mentee:

I met her in my final year in graduate school when I went to a Chicano symposium in California. My friend and I just wanted to touch her. It was just so amazing to see a Latina psychologist for the first time. She was amazing. She was absolutely phenomenal. We asked her to chair a symposium for us at an APA convention the following year or so. She did and she had us practice in her room to give us feedback before we actually did the presentation. She just went out of her way to try to groom us and help us become fully functional professionals and psychologists. Our paths crossed several times through APA boards and committees. She was a leader, and she had a great sense of humor and she cared very much about helping younger psychologists find their way. I cannot say enough about how wonderful she was. We were very, very sad when she died but her spirit and her inspiration live on in all of us (Vasquez, 2021, personal communication).

Judith E. Favell

Judith E. Favell is the sole living inductee from the class of 2021. Favell was born Judith Elbert in 1944. She received her undergraduate degree in psychology in 1966 from Illinois Wesleyan University and her PhD in developmental and child psychology from the University of Kansas Department of Applied Science in 1970. It should be noted that she has been honored as a Distinguished Alumnist from each of these institutions.

She and her then husband, Jim Favell, moved to the Western Carolina Center where they had two daughters, Holly and Katherine. Judy served in several positions at the Western Carolina Center, ultimately in the role of clinical director. In 1987, she moved to an organization that eventually become AdvoServ where she served in multiple roles including clinical director, chief executive officer, and chairman of the board. In these important clinical and administrative roles, she experienced “the power of our behavioral tools and the realities and mysteries that limited our outcomes... learned the myriad of influences and counter contingencies that impact behavior change... learned about the point where the rubber hits the road: where behavior analysis meets the real world, hopefully to the benefit of both” (Favell, 2015, personal communication).

Judy Favell served an important role in advocating for the rights of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and autism spectrum disorders as well as in the evolution of the profession of behavior analysis. She provided critical expert testimony in several legal cases that proved critical to expanding the rights of those with disabilities. She served as a leader for several professional organizations including the Florida Association of Behavior Analysis, Divisions 25 and 33 of the American Psychological Association, the Association for Behavior Analysis International, the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts, and the Behavior Analyst Certification Board. In particular, her leadership roles for the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts and her terms as president of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board were instrumental in professionalizing the practice of behavior analysis (see Fig. 11). Her visible leadership roles established her as a role model for women in behavior analysis and her wisdom and insight about professional politics have made her a valuable mentor to subsequent generations of leaders.

Fig. 11.

Judy Favell discussing issues facing the profession at the behavior analyst certification board dedication of the gerald shook conference room. Photo credit: James E. Carr

Speaking about these aspects of her career, Jane Howard said:

We are a lucky bunch because we have Judy in all her glory: the behavior analyst par excellence, the leader, the iconoclast. Judy’s gifts to the next generation of behavior analysts include her writings, her work in public policy, and professional leadership among others. Judy has an amazing ability to provide hard truths in a way that makes the listener understand that she is genuinely on their side. She is hilarious and kind, and she is the person I most want in the foxhole with me. (Jane Howard, personal communication)

The CEO of the BACB at the time of this writing, Jim Carr, served first as a board member with Judy and the subsequently as CEO with her as president of the board and said:

As President of the BACB’s Board of Directors, Judy led the organization during an incredibly difficult period through an emergency leadership transition, strife within behavior analysis, and conflict with other professions. Judy Favell is, hands down, the most effective behavior analyst I know. Her intellect, strategic thinking, political savvy, and personal skills are awe-inspiring. Judy has accomplished he many amazing feats while dealing with broken glass from many ceilings. Our profession, our science, and our clients all benefitted from the force of nature that is Judy Favell. (James Carr, personal communication)

Favell has over 100 publications including books, chapter, and experimental studies, and some of her most influential works helped to establish the parameters of individual rights to effective treatments and therapeutic environments (Van Houten et al., 1988; Favell & McGimsey, 1993). She served as the co-editor of the journal Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities. Her scholarship and leadership have been honored and celebrated through induction as a fellow in five different professional organizations. In addition, she has received the Sidman award for Enduring Contribution to Applied Behavior Analysis from the Berkshire Association for Behavior Analysis and Therapy and the G. L. Shook Award for Contributions to the Practice of Behavior Analysis from the California Association for Behavior Analysis.

In summary, Judy Favell has given innumerable gifts to behavior analysis. She has served as a role model and created infrastructure to allow the growth of professional behavior analysis. Bridget Taylor, CEO of Alpine Learning Group, has perhaps said it best when she said:

They say that true brilliance is harnessing your own knowledge specifically for the benefit of those around you. Our field, its practitioners, and the human lives we touch have all benefitted immeasurably from the radiance of Judy’s brilliance. Always generous with her knowledge and spirit, Judy inspires both a sense of wonder at what the science makes possible and the commitment to honor that wonder by sharing it, again and again, with others. (Bridget Taylor, personal communication)

Conclusion

Our profession can take pride in the gathering and honoring the contributions of the female founders of our field and those who have created opportunities for the next generation of behavior analysts. These amazing women, along with many more future inductees, were there, but in the shadows and not always fully recognized and honored. Through the efforts of the WIBA Hall of Fame, we bring them and their efforts into the foreground and illustrate the legacy they have left as a gift and source of strength for all behavior analysts.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflict of interest

Devon Sundberg is the co-founder and conference director of WIBA and has a financial interest in WIBA since 2017.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ballie, R. M. (2002, January). Martha E. Bernal dies at age 70. Monitor on Psychology, 33(1). https://www.apa.org/monitor/jan02/latina.

- Bernal, M. E. (1988). Chapter 17: Martha E. Bernal. In: A. N. O’Connell & N. F. Russo, (Eds.), Models of achievement: Reflections of eminent women in psychology (261–278). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bernal ME, Knight GP, Garza CA, Ocampo KA, Cota MK. Development of ethnic identity in Mexican-American children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12(1):3–24. doi: 10.1177/07399863900121001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binder, C. V. (2004). Beatrice H. Barrett (1929–2003). American Psychologist, 59, 561. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.6.561.

- Favell, J. E., & McGimsey, J. F. (1993). Defining an acceptable treatment environment. In R. Van Houten and S. Axelrod (Eds.), Behavioral analysis and treatment (25–45). Plenum Press.

- Gilbert R. Evalyn Finn Segal, in memoriam. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2017;107(2):203–207. doi: 10.1002/jeab.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K, Street EM, Neely MD. Precision teaching: Fluency and agility. In: Haring NG, White MS, Neely MD, editors. Precision teaching: A practical science of education. Sloan Publishing; 2019. pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, F. S., & Schoenfeld, W. N. (1950). Principles of psychology: A systematic text in the science of behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Li A, Curiel H, Pritchard J, Poling A. Participation of women in behavior analysis research: Some recent and relevant data. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(2):160–164. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0211-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E. K. (2003). Ellen P. Reese (1926–1997). The Feminist Psychologist, 30.

- Morris, E. (2018). On the history of women in behavior analysis. Paper presented at the Women in Behavior Analysis Conference, Nashville, TN.

- Nosik MR, Luke MM, Carr JE. Representation of women in behavior analysis: An empirical analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2018;19(2):213–221. doi: 10.1037/bar0000118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennypacker, H. S., Gutierrez, A., & Lindsley, O. R. (2003). Handbook of the standard celeration chart. Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies.

- Segal EF. Toward a coherent psychology of language. In: Honig WK, Staddon JER, editors. Handbook of operant behavior. Prentice-Hall; 1977. pp. 628–653. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, E. F. (1982, August). Women, borscht, gays, laboratory animals, and nuclear extinction. [Invited address to Divisions 25 and 9] American Psychological Association Annual Convention, Washington, DC. https://www.scribd.com/document/338313756/Segal-1982-APA-Presentation.

- Segal EF. Walden Two: The morality of anarchy. The Behavior Analyst. 1987;10(2):147–160. doi: 10.1007/BF03392425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal, E. F. (1988, February). B. F. Skinner Interviewed in his office at Harvard University. [Video]. Behavior Analysis History. https://tinyurl.com/SegalSkinnerInterview.

- Segal, E. F. (Ed.) (1989). Housing, care and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates. Noyes Publications.

- Segal, E. F. (1972). Induction and the provenance of operants. In R. M. Gilbert & J. R. Millenson (Eds.), Reinforcement: Behavioral analyses (pp. 1–34). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-283150-8.50006-X.

- Sundberg DM, Zoder-Martell KA, Cox S. Why WIBA? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):810–815. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00369-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten R, Axelrod S, Bailey J, Favell JE, Foxx R, Iwata B, Lovaas I. The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21(4):381–384. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez, M. (2010). Biography of Martha Bernal. American Psychological Association. https://www.apadivisions.org/division-35/about/heritage/martha-bernal-biography.

- Vasquez, M. J. T., & Lopez, S. (2002). Martha E. Bernal (1931–2001): Obituary. American Psychologist, 57(5), 362–363. 10.1037/0003-066X.57.5.362.

- Wesolowski, M. D. (2002). Pioneer profiles: A few minutes with Sid Bijou. The Behavior Analyst, 25, 15–27 (2002). 10.1007/BF03392041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zahidi, S., Geiger, T., & Crotti, R. (2018). The global gender gap report 2018. World Economic Forum.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.