Abstract

Mitochondria need to use considerable energy for the intracellular organelles that produce ATP. They are abundant in the cells of organs, such as muscles, liver, and kidneys. The heart, which requires a lot of energy, is also rich in mitochondria. Mitochondrial damage can induce cell death. Doxorubicin, acetaminophen, valproic acid, amiodarone, and hydroxytamoxifen are representative substances that induce mitochondrial damage. On the other hand, the effects of this substance on the progress of cardiomyocyte-differentiating stem cells have not been investigated. Therefore, a 3D cultured embryonic body toxicity test was performed. The results confirmed that the cytotoxic effects on cardiomyocytes were due to mitochondrial damage in the stage of cardiomyocyte differentiation. After drug treatment, the cells were raised in the embryoid body state for four days to obtain the ID50 values, and the levels of mRNA expression associated with the mitochondrial complex were examined. The mitochondrial DNA copy numbers were also compared to prove that the substance affects the number of mitochondria in EB-state cardiomyocytes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43188-022-00161-1.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Embryonic stem cell test, Alternative toxicity test

Introduction

The mitochondria are organelles in all mammalian cells except red blood cells. Mitochondria contain their own genome, called the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which encodes essential subunits of the respiratory chain wherein electrons are combined with oxygen to allow energy flow through mitochondria [1]. In the mitochondria, for cellular respiration, there are several respiratory chain complexes. The proton pumping complexes of the electron transfer system are complex I, complex III, and complex IV [2–4]. Complex II does not pump protons but contributes to reduced ubiquinone in the mitochondria [5]. Complex V carries out a multistep process called oxidative phosphorylation, through which cells derive energy as an ATP synthase [6]. Because mitochondrial ATP synthesis and efflux outside mitochondria is a multistep process requiring intact-coupled mitochondria and occurring in a manner regulated by the rate-limiting step, damage to the mitochondria causes cell damage through a biochemical process [7]. mtDNA is prone to mutations caused by a lack of protective histones, low-fidelity DNA polymerase activity, and continuous exposure to the mutagenic effects of oxygen radicals [1]. Hence, mtDNA damage and changes in the mitochondrial DNA content have been implicated in various diseases and mitochondrial dysfunction. For a normal cell and mitochondrial function, the cells must maintain the integrity of their nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Therefore, the mtDNA copy number is also a biomarker for mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, damaged mitochondria induce a propensity to trigger cell proliferation inhibition by generating harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS).

In 2014, Morén et al. examined the mitochondrial toxicity in human pregnancy. They reported an association between exposures to mitochondrial toxic agents ranging from fertility defects, detrimental fetal development, and impaired newborn health due to intra-uterine exposure [8]. The early embryonic development process is important for successful implantation and fetal development [9, 10]. During the cleavage stage of early embryos, exposure to toxic substances will lead to oxidative stress and DNA damage, which can lead to developmental failure [9]. Exposure to substances that induce mitochondrial toxicity at each stage of development affects the cell viability, formation of compensatory bodies, and normal differentiation [8, 11]. Moreover, a mitochondrial dysfunction at the developmental stage can impair fetal brain development and affect embryonic and adult neurogenesis [11].

Increased requirement and advances within the scientific field has brought the development of alternative methods for the toxicity testing. In despite of the attempts to reduce, replace and refine the number of animal used in the laboratory experiment arise steeply. Currently, efforts are being made for validating alternative tests [12–14]. The alternative methods has become inevitable, which can give a chance to reduction in the number of animal use in laboratory experiments, especially for improving toxicological assessment procedures and even for the replacement of animal use with in vitro stem cell tests or in silico system.

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are a cell line that can differentiate into developing stage ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm [15]. The embryonic body test (EBT) takes advantage of the properties of this cell line to replace in vivo developmental toxicity [13, 14, 16]. EBT can reflect the cytotoxicity in undifferentiated cells and fibroblasts and assess the growth retardation and embryonic lethality from the cross-sectional area of EB [16]. In previous studies have shown that EBT can be used to distinguish between toxic and non-toxic materials, but more studies will be needed to examine the precise mechanism of toxicity for the possible toxicants. The discriminated toxicants caused by EBT help stabilize and activate of TP53. TP53 is involved in several important cellular processes, including the induction of cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, apoptosis, and autophagy, as well as inhibition of metabolism, angiogenesis, and cell migration [16, 17].

This study assessed the toxicity of five representative mitochondrial damage-inducing substances (doxorubicin, acetaminophen, valproic acid, amiodarone, and hydroxytamoxifen). Doxorubicin targets the cellular mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial damage and cell death. Acetaminophen, in case of overdose, induces mitochondrial oxidative stress, which amplifies mitochondrial defects. Valproic acid induces mitochondrial perspiration dysfunction; Amiodarone increases mitochondrial oxidative stress; Hydroxytamoxifen induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial apoptosis via stimulating mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. This study evaluated the EBT-based cell viability of 3t3-L1 and mES cells and embryonic body formation. After determining the toxic dosage, mitochondria-related gene expression (complex I-V) and antioxidant enzymes (catalase and superoxide dismutase) were measured. Subsequently, the following results were confirmed: the EBT, mtDNA copy number increase, and mitoSOX staining, which are used widely to detect mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially superoxide. Similar tendencies were observed between EBT and mitochondrial damage. These results can support the use of EBT testing methods to screen possible mitochondria damaging materials.

Materials and methods

Cell line and cell culture

The mESC used in the experiment was an ES-E14TG2a cell line purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and used. These cells are capable of differentiating into the myocardium. In the medium composition for maintaining undifferentiated, DMEM/F12 (1:1) (Gibco, Logan, UT, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1X non-essential amino acid (NEAA, Gibco), Plasmacine, 100 U/mL Penicillin and 100ug/mL Streptomycin, 10−4 M 2-mercaptoeathanol, mouse leukemia inhibitory factor (mLIF, 10 ng/mL; Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) were added. As the medium composition for inducing differentiation, the content of FBS was increased to 15% in the undifferentiated medium and mLIF was not added. The cells were grown in 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified tissue culture incubator (Sanyo, San Diego, CA, USA).

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (mEFs) were used for feeder cells as one of the elements for growing cells. mEF was obtained by isolating embryo with 11 days pregnant ICR mouse (Koatech, Gyeonggido, South korea). For the detailed experimental method, refer to EBT related articles [13, 14, 16].

Cytotoxicity

Cells were seeded on 96 well plates with 800 cells/well in 50 μl culture media. After incubation for 2 h, it was diluted 1.333 times the concentration to be treated to create a drug badge and treated 150 μl per well. Then, after culturing in an incubator for 4 days, a CCK assay was performed using an EZ cytox solution (DoGenBio, Seoul, South korea). After removing all existing drug badges, wash once with DPBS, mix pure DMEM/F12 (1:1) media and EZ cytox solution at a ratio of 10:1, and then treat 110 μl per well. And then Incubated for 1 h. Then, the absorbance was measured at 450 wavelengths using a SYNERGY H1 microplate reader (Biotek instrument, Winooski, VT, USA). For cell viability, the relative absorbance values were compared with the absorbance of the solvent control set to 100%. IC50 calculated the value that appears when 50 is substituted for the value of y in the trend line formula of the graph.

Hanging drop

For the basic experimental method, the EBT related articles have been reffered [13, 14, 16]. To put it briefly, the drug was not treated or treated by concentration in the differentiation medium, and after 1 drop became 20 ul and 800 cells could be contained, the petri dish was 8 × 7 + 6 × 2 + 4 × 4 = 84 drops were dispensed. Then, the cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37° for 72 h. The cultured embryonic body (EB) was photographed with an optical microscope (Olympus, Japan, Tokyo) at a magnification of 100 ×, and then ID50 value about EB area was analyzed using NIH ImageJ(NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5(San Diego, CA, USA) software.

Prediction model (PM)

The IC50 value obtained using the undifferentiated mESC and the IC50 value obtained using the 3T3-L1 cells are based on the ID50, which is the area of the compensatory body obtained using the hanging drop, in the previous paper. By substituting into the predicted model given, it is possible to determine whether a substance is toxic or not.

Concentration–response curves were generated for each test chemical and a one-site fit to a three-parameter logistic function was obtained by using GraphPad Prism (v6.01). The IC50E14, IC503T3, ID50EB, values were used to classify the compounds as nontoxic and toxic categories. A linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was used to identify endpoints via stepwise discriminant analysis (SPSS). A proportional a priori probability was calculated from the equal sample sizes of the four classes. The classified results were confirmed by applying leave-one-out cross-validation in which out of a group of 24 cases (n) every single case is classified by the remaining 23 cases (n − 1). The variables selected by that process were log (IC503T3), log (IC50E14), and [(IC50E14 − ID50EB)/IC50E14].

If the value obtained by substituting this formula is lower than 0.667, it is classified as non-toxic, otherwise it is classified as toxic. For details on this prediction model, refer to the previous paper [13, 14, 16].

Beating ratio

The compensatory bodies cultured in the hanging drop were collected and stabilized in the petri dish for 28 h. After that, 5–7 EBs each well were attached to the 6-well plate, and beating was observed and media was changed at 2-day intervals.

RNA extraction and qPCR

RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Invotrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). And cDNA was synthesized using 1ug RNA and MMLV kit (Invotrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR mixture are included 2XSYBR Premix Ex Taq, Rox dye, each primers, and distilled water. SYBR PCR (TaKaRa Bio Inc.) was used flouroscence dye in qPCR (QuantStudio3, applied biosystems, Poster city, CA, USA) qPCR was performed under the following conditions: 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Fluorescence intensity was measured at the end of the extension phase of each cycle.

DNA extraction and mitochondrial DNA copy number

DNA was extracted using the G-DEXTM IIc for Cell/Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction kit (iNtRON biotechnology, Seongnam, South Korea). The detailed experimental method followed the manufacturer's protocol. For Nuclear DNA, Calbindin-D9K gene, which is one of the single copy DNAs, was selected. Mitochondrial DNA used a reference gene to calculate copy number [18–21]. Using qPCR, calculated relative mitochondrial DNA copy number. Relative mitochondrial DNA copy number was determined using a comparative ΔΔCt(mtDNA-nuDNA) value.

MitoSOX staining

The MitoSOX™ Red mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) can detect cells damaged by ROS. In this study, 800 cells per well were seeded on a 96-well plate and cultured at 37° for 3 days in a 5% CO2 wet incubator. Then, pure DMEM/F12 (1:1) was diluted with mitoSOX stock (5 mM) at 5 μM and Hoechst 33,342 at 12 μg/ml and treated at 120 μl/well. After 10 min of incubation, it was washed twice with DPBS and then analyzed at a wavelength of 510/580 nm using a SYNERGY H1 microplate reader (Biotek instrument, Winooski, VT, USA).

Statistic

Significant differences were detected by using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. The analysis was performed using the Prism Graph Pad v8.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Values are expressed as means ± SD of at least three separate experiments, in which case a representative result is depicted in the figures. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

EBT assay results of five representative mitochondria-toxic chemicals

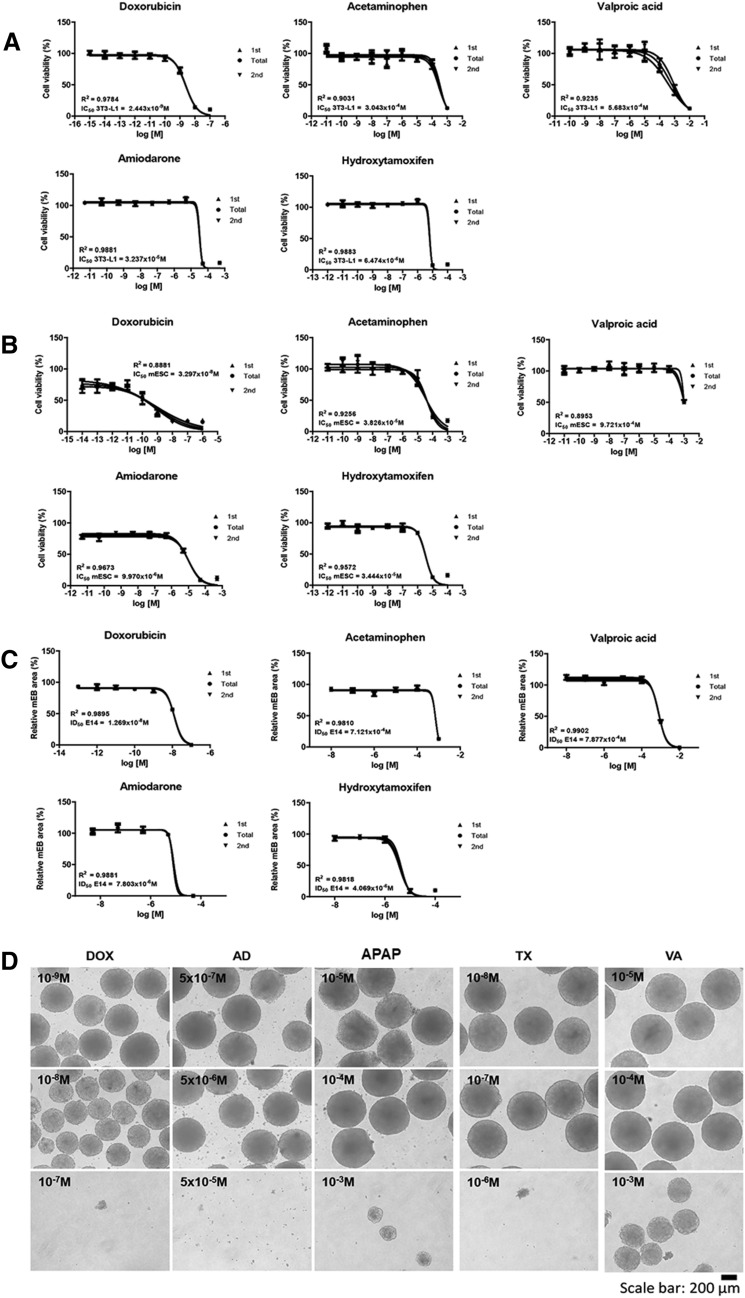

Doxorubicin, acetaminophen, valproic acid, amiodarone, and hydroxytamoxifen are toxic to mitochondria. An EBT test, including the 3T3-L1/mES cell viability and embryonic body (EB) formation, revealed doxorubicin to show toxicity in the 10−9–10−8 M range; acetaminophen and valproic acid showed toxicity in the 10−5–10−4 M range; amiodarone and hydroxytamoxifen showed toxicity in the 10−6–10−5 M range (Fig. 1a, b). The classification of five toxic materials in a previous study was based on discriminant function (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

EBT results of five chemicals (Doxorubicin, acetaminophen, valproic acid, amiodarone, and hydroxytamoxifen). Cell viability against 3T3-L1 cell (a), mES (b), and inhibition of EB formation (c). Reduction in EB size depending on toxic strength of chemicals under the same concentration condition. The EBs were formed over 3 days via the hanging drop method with five chemicals. Scale bars mean 200 μm

Table 1.

The classification of five toxic materials

| Chemicals | LogIC50 mES | LogIC50 3T3-L1 | LogID50 EB | Class | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | − 4.417 | − 3.517 | − 3.147 | T | 3.443 |

| Doxorubicin | − 12.37 | − 8.433 | − 7.896 | T | 9.088872 |

| Hydroxytamoxifen | − 3.012 | − 5.189 | − 5.391 | T | 3.262083 |

| Valproic acid | − 5.463 | − 3.245 | − 3.104 | T | 3.827375 |

| Amiodarone | − 5.001 | − 4.490 | − 5.108 | T | 3.916293 |

Discriminant function = − 0.4852526 × log10 IC50(ESC) − 0.5251880 × log10 IC50 (3T3) + 0.1700371 × log10 ID50 (EB)

N non-toxic, T toxic

Based on the dosages showing decreased cell viability, inhibitions of EB formation due to five toxic materials were examined (Fig. 1c, d). As shown in Fig. 2, the size of the embryoid bodies (EBs) decreased by half by doxorubicin (1.3 × 10−8 M), acetaminophen (7.1 × 10−4 M), valproic acid (7.9 × 10−4 M), amiodarone (7.8 × 10−6 M), and hydroxytamoxifen (4.1 × 10−6 M).

Fig. 2.

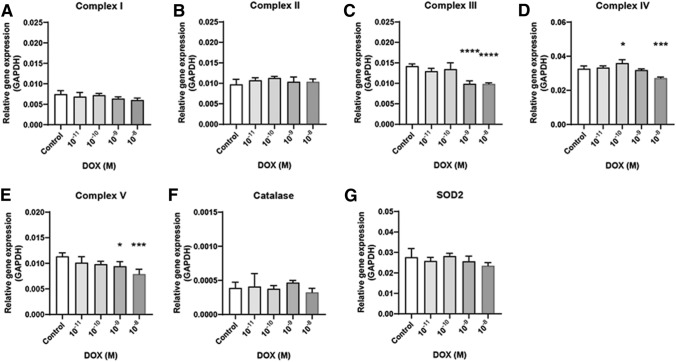

Mitochondria related gene expression in doxorubicin exposed EB. mRNA expressions of Complex I (a), II (b), III (c), IV (d), V (e), catalase (f), and [Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2), g]. The dosage start from 10–11 to 10–8. Results are normalized with GAPDH. Each samples for mRNA expression was examined at day 4 (EB state). n = 12 in each group, *p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. ****P ≤ 0.0001

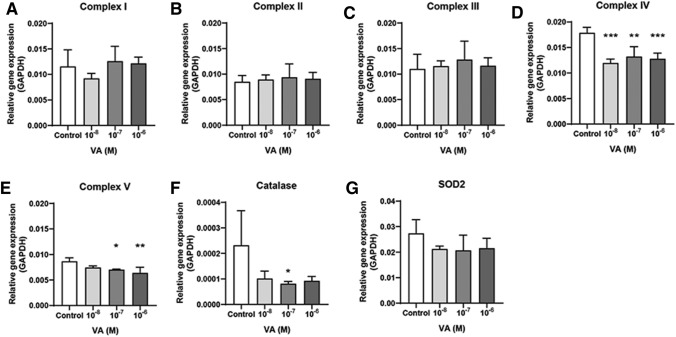

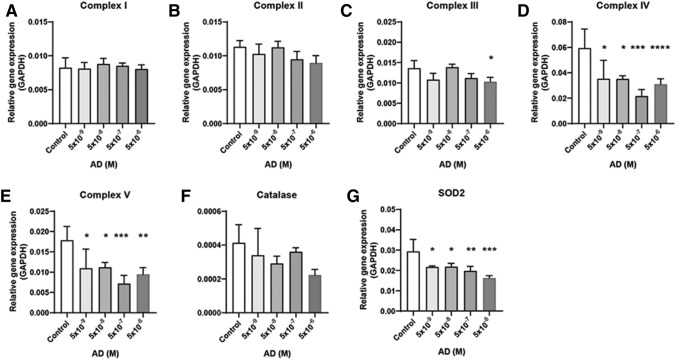

Mitochondria-related gene and antioxidant genes expression in embryonic bodies

The dosage of the five chemicals was determined based on the 3T3-L1/mES cell viability and EB formation. After treating the cells with five chemicals, the levels of mRNA expression associated with the mitochondrial complex in the EB state and antioxidant enzyme catalase and SOD2 were examined by qPCR. The dosage that promoted a decrease in cell viability and EB formation showed a decreased expression level of mitochondrial complex genes. In the case of doxorubicin, complex III, IV, and V mRNA expressions were decreased at 10−8 M dosage (Fig. 2). The acetaminophen treatment decreased complex V expression only at 10−7–10−4 M dose (Fig. 3). Valproic acid decreased complex IV (10−8–10−6 M) and V (10–7–10–6 M) expression (Fig. 4). Amiodarone decreases the expression of complex III (10−6 M), IV (10−9–10−6 M), and V (10−9–10−6 M) (Fig. 5). On the other hand, hydroxytamoxifen does not decrease any complex mRNA expression but increases the mRNA expression of complex II and III at the highest dose (10−5 M) (Fig. 6). The antioxidant genes that increased with increasing incidence of mitochondrial damage with hydroxytamoxifen but decreased with valproic acid at high doses (10−7–10−8 M).

Fig. 3.

Mitochondria related gene expression in acetaminophen exposed EB. mRNA expressions of Complex I (a), II (b), III (c), IV (d), V (e), catalase (f), and [Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2), g]. The dosage start from 10–11 to 10–8. Results are normalized with GAPDH. Each samples for mRNA expression was examined at day 4 (EB state). n = 12 in each group, *p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. ****P ≤ 0.0001

Fig. 4.

Mitochondria related gene expression in valproic acid exposed EB. mRNA expressions of Complex I (a), II (b), III (c), IV (d), V (e), catalase (f), and [Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2), g]. The dosage start from 10–11 to 10–8. Results are normalized with GAPDH. Each samples for mRNA expression was examined at day 4 (EB state). n = 12 in each group, *p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. ****P ≤ 0.0001

Fig. 5.

Mitochondria related gene expression in amiodarone exposed EB. mRNA expressions of Complex I (a), II (b), III (c), IV (d), V (e), catalase (f), and [Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2), g]. The dosage start from 10–11 to 10–8. Results are normalized with GAPDH. Each samples for mRNA expression was examined at day 4 (EB state). n = 12 in each group, *p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. ****P ≤ 0.0001

Fig. 6.

Mitochondria related gene expression in hydroxytamoxifen exposed EB mRNA expressions of Complex I (a), II (b), III (c), IV (d), V (e), catalase (f), and [Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2), g]. The dosage start from 10–11 to 10–8. Results are normalized with GAPDH. Each samples for mRNA expression was examined at day 4 (EB state). n = 12 in each group, *p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. ****P ≤ 0.0001

Summarizing the above results, although the mechanism of mitochondrial damage differs, complex IV and V expression were reduced significantly when mitochondrial toxicity occurred with these five chemicals.

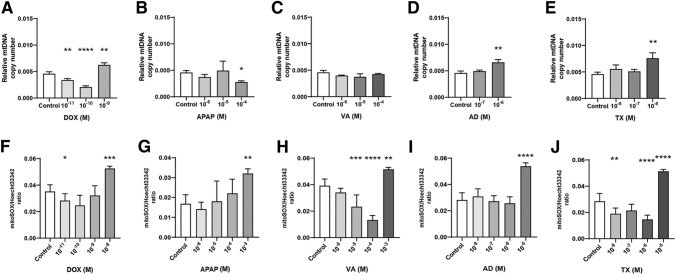

Changes in mitochondrial DNA copy numbers due to five mitochondria-toxic chemicals

A change in mtDNA copy number is a biomarker indicating mitochondrial damage [22, 23]. Doxorubicin increased the mtDNA copy number at 10−9 M, which is near the ID50 value for EB formation (1.3 × 10−8 M). Acetaminophen decreased mtDNA at 10−4 M dose, also a similar range of ID50 value for EB formation (7.1 × 10−4 M). The amiodarone (10−6 M) and hydroxytamoxifen (10–6 M) treatments increased mtDNA expression (ID50 value for EB formation: 7.8 × 10−6 M and 4.1 × 10−6 M, respectively). Only valproic acid did not show an increase in mtDNA expression in the range of dose (from 10−6 to 10−4 M) compared to its ID50 for EB formation (7.9 × 10−4 M) (Fig. 7a–e).

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial damage indicators including DNA copy number change and mitoSOX staining intensity. Mitochondrial DNA copy numbers of doxorubicin (DOX, a), acetaminophen (APAP, b), valproic acid (VA, c), amiodarone (AD, d), and hydroxytamoxifen (TX, e) were measured real-time PCR. Mitochondrial DNA used a reference gene to calculate copy number. After 4 days of exposure of doxorubicin (f), acetaminophen (g), valproic acid (h), amiodarone (i), and hydroxytamoxifen (j), mitoSOX staining intensity was analyzed. As Mitochondrial ROS increases, mitoSOX intensity also increases. n = 6 in each group, *p ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001

MitoSOX staining intensity analysis in four days of exposure to five mitochondria-toxic chemicals

The mitochondrially targeted MitoSOX dye was used to measure mitochondrial superoxide. MitoSOX is a mitochondria-targeted fluorescent dye that is oxidized by superoxide in the mitochondria to ethidium. The ethidium then intercalates into the mitochondrial DNA and produces fluorescence proportional to mtROS [24]. As mitochondrial ROS increases, mitoSOX intensity also increases. Similar data for mitochondrial gene expression was obtained. The highest dose of five mitochondria-toxic chemicals showed an increased intensity of mitoSOX. Doxorubicin (10−8 M), acetaminophen (10−3 M), valproic acid (10−3 M), amiodarone (10−5 M), and hydroxytamoxifen (10–5 M) increased the mitoSOX intensity normalized to hoecht33342 at a dose of (ID50 value for EB formation: 7.1 × 10−4 M, 7.1 × 10−4 M, 7.9 × 10−4 M, 7.8 × 10−6 M, and 4.1 × 10−6 M, respectively) (Fig. 7f–j).

Discussion

Alternative toxicity tests are necessary to assess the safety or screen hazardous substances associated with various fields [25]. Developing an in vitro development toxicity test method can reduce the number of laboratory animals used to assess the toxicity of chemicals and provide women of childbearing age with information on the safety of various chemicals by assessing developmental toxicity [26, 27]. In two decades, many studies have evaluated alternative toxicity tests with embryonic stem cells [28, 29]. Stem cells can differentiate into any of the three germ layers by forming embryoid bodies (EBs), which are three-dimensional multicellular aggregates [16]. The authors have continually studied alternative toxicity testing using embryonic stem cells and its intermediate differentiated form, EB [12–14, 16, 30–32]. EB, the intermediated form of differentiation, can be used for toxicity testing at the stage of development [31]. Chemical treatment resulted in dose-dependent decreases in the EB area via epigenetic inhibition of differentiation and cell cycle arrest [16, 32]. The mechanisms of the diminishing EB size vary, and the causes of the decreased EB size due to toxic chemical treatment were examined. Doxorubicin, acetaminophen, valproic acid, amiodarone, and hydroxytamoxifen are toxic to the mitochondria. The mitochondria produce energy in the form of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation. Normal mitochondrial dynamics are critical for cellular function, embryonic development, and tissue formation [33, 34]. Thus, defects in proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics affect cellular differentiation. This study focused on the changes to expose toxic material, whether the embryonic stem cell testing method can screen toxic substances, and identify its mechanism.

Mitochondrial toxicity mechanism of each chemical was well described in Massart et al. [35]. In more detail, comparing the results of previous studies with those of this study, doxorubicin is known to overproduce ROS and cause oxidative stress [36], but this study did not significantly affect the gene expression of catalase and SOD2. On the other hand, it was confirmed that mtDNA and the key marker of mitochondrial superoxide had significant results on the high concentration of doxorubicin. When acetaminophen is exposed to overdose, it causes high levels of NAPQI, which binds abnormally to proteins inside the mitochondria, making it impossible to perform detoxification [37]. Complex II is very sensitive in inhibiting the effects of NAPQI [35], which is similar results showing changes in various gene expressions in mitochondrial complexes, including Complex II. Valproic acid is known to cause inactivation of CPT-1, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and disruption of fatty acid oxidation [38]. Valproic acid was found that it responded most sensitively to the superoxide marker. This result shows that it is the same propensity as the previous research results. It has been reported that amiodarone affects mitochondrial resistance and oxidative phosphorylation in a dose-dependent [35]. This study also showed similar tendency in most results except for the highest concentration. For 4-hydroxytamoxifen, it is known as increasing the mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [39]. This study showed the most remarkable changes in superoxide when exposed to high concentrations. To comprehensively estimate these results, it is not possible to determine mitochondrial toxicity with only one indicator, but necessary to confirm the dynamics of the chemical using the diverse indicator.

This study examined the effects of mitochondrial toxicity before, during, and after the differentiation of mouse stem cells. Exposure to chemicals toxic to the mitochondria prior to differentiation and exposure during differentiation affect the stem cell cytotoxicity. Exposure to these five chemicals, which were already confirmed as mitochondrial-toxic materials, confirmed that the embryonic stem cell test could screen their toxicity according to the 3T3-L1/mES viability and EB formation assay. Table 1 showed that it survived at higher concentrations when cultured in 3D than when cultured with 2D monolayer. These results suggest that there are more complex self-protection mechanisms in the 3D state than when exposed to drugs in the monolayer. It suggests that confirming the effect of drugs in various aspects or states can prevent the fallacy of generalization. The expression pattern at the mRNA levels of the five chemical treated samples showed that they mainly affect mitochondrial complex IV and V. Mitochondrial complex IV, also called cytochrome c oxidase, promotes the transfer of electrons from reduced cytochrome c to the final acceptor, O2 [40]. Complex V, called F0F1 ATP synthase, helps synthesize ATP efficiently in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. [41, 42]. For this, a proton motive force (PMF), including a proton concentration gradient across the mitochondrial membrane (ΔpH) and an electric membrane potential (ΔΨ), is required [42]. The reduction of gene expression related to the two complexes showed that the chemicals used in the experiment inhibited electron transport and ATP synthesis. mtDNA and mtROS data are shown ROS indicated damage would be at the higher concentration of mitochondria damaging chemicals treatment while ROS increase is preceded to mtDNA copy number increase. In the range of treated chemical concentration, mtDNA are decreased except for doxorubicin and hydroxytamoxifen. Therefore the decrease of EB size and cellular toxicity ranges of each chemical has less relation for the mitochondrial damage with ROS. Wang et al. described the decreased cellular levels of mtDNA clinically correlate with mitochondrial disorders mitochondria. Therefore specific mechanisms regulate mtDNA copy number in response to ROS [43].

In conclusion, chemicals toxic to the mitochondria were identified by applying them to EBT. In addition, the gene expression of mitochondrial complexes IV and V-related enzymes was decreased significantly at a similar dose to the EBT-based dose determination. As a result, this model can confirm mitochondrial toxicity in a 3D culture. This research is expected to contribute to establishing advanced embryonic stem cell testing, which can screen for developmental toxicity chemicals.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection were performed SHJ and analysis were performed by CA and EBJ. CA wrote the manuscript and EBJ reviewed and supervised the manuscript writing. All authors have read and agreed to the publish version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (no. 2021R1A2C2093275).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial interests.

Footnotes

Changhwan Ahn and SunHwa Jeong contributed equally.

References

- 1.Kim JI, Lee SY, Park M, Kim SY, Kim JW, Kim SA, Kim BN. Peripheral mitochondrial DNA copy number is increased in korean attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:506. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdrakhmanova A, Zwicker K, Kerscher S, Zickermann V, Brandt U. Tight binding of NADPH to the 39-kDa subunit of complex I is not required for catalytic activity but stabilizes the multiprotein complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1676–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acin-Perez R, Bayona-Bafaluy MP, Fernandez-Silva P, Moreno-Loshuertos R, Perez-Martos A, Bruno C, Moraes CT, Enriquez JA. Respiratory complex III is required to maintain complex I in mammalian mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2004;13:805–815. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsa E, Marco R, Perales-Clemente E, Szklarczyk R, Calvo E, Landazuri MO, Enriquez JA. NDUFA4 is a subunit of complex IV of the mammalian electron transport chain. Cell Metab. 2012;16:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang LS, Sun G, Cobessi D, Wang AC, Shen JT, Tung EY, Anderson VE, Berry EA. 3-nitropropionic acid is a suicide inhibitor of mitochondrial respiration that, upon oxidation by complex II, forms a covalent adduct with a catalytic base arginine in the active site of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5965–5972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511270200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kucharczyk R, Zick M, Bietenhader M, Rak M, Couplan E, Blondel M, Caubet SD, di Rago JP. Mitochondrial ATP synthase disorders: molecular mechanisms and the quest for curative therapeutic approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atlante A, Amadoro G, Bobba A, de Bari L, Corsetti V, Pappalardo G, Marra E, Calissano P, Passarella S. A peptide containing residues 26–44 of tau protein impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation acting at the level of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1289–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moren C, Hernandez S, Guitart-Mampel M, Garrabou G. Mitochondrial toxicity in human pregnancy: an update on clinical and experimental approaches in the last 10 years. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:9897–9918. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110909897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu LL, Liao BY, Wei JX, Ling YL, Wei YX, Liu ZL, Luo XQ, Wang JL. Podophyllotoxin exposure causes spindle defects and DNA damage-induced apoptosis in mouse fertilized oocytes and early embryos. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:600521. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.600521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teh WT, McBain J, Rogers P. What is the contribution of embryo-endometrial asynchrony to implantation failure? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1419–1430. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0773-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khacho M, Clark A, Svoboda DS, MacLaurin JG, Lagace DC, Park DS, Slack RS. Mitochondrial dysfunction underlies cognitive defects as a result of neural stem cell depletion and impaired neurogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:3327–3341. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong S, Park SM, Jo NR, Kwon JS, Lee J, Kim K, Go SM, Cai L, Ahn D, Lee SD, Hyun SH, Choi KC, Jeung EB. Pre-validation of an alternative test method for prediction of developmental neurotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022;164:113070. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Park SY, Ahn C, Kim CW, Kim JE, Jo NR, Kang HY, Yoo YM, Jung EM, Kim EM, Kim KS, Choi KC, Lee SD, Jeung EB. Pre-validation study of alternative developmental toxicity test using mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;123:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Park SY, Ahn C, Yoo YM, Kim CW, Kim JE, Jo NR, Kang HY, Jung EM, Kim KS, Choi KC, Lee SD, Jeung EB. Second-phase validation study of an alternative developmental toxicity test using mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020;71:223–233. doi: 10.26402/jpp.2020.2.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murry CE, Keller G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell. 2008;132:661–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang HY, Choi YK, Jo NR, Lee JH, Ahn C, Ahn IY, Kim TS, Kim KS, Choi KC, Lee JK, Lee SD, Jeung EB. Advanced developmental toxicity test method based on embryoid body's area. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;72:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.06.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toma-Jonik A, Vydra N, Janus P, Widlak W. Interplay between HSF1 and p53 signaling pathways in cancer initiation and progression: non-oncogene and oncogene addiction. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2019;42:579–589. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rooney JP, Ryde IT, Sanders LH, Howlett EH, Colton MD, Germ KE, Mayer GD, Greenamyre JT, Meyer JN. PCR based determination of mitochondrial DNA copy number in multiple species. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1241:23–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1875-1_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdullaev S, Gubina N, Bulanova T, Gaziev A. Assessment of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, expression of mitochondria-related genes in different brain regions in rats after whole-body X-ray irradiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1196. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bordoni L, Smerilli V, Nasuti C, Gabbianelli R. Mitochondrial DNA methylation and copy number predict body composition in a young female population. J Transl Med. 2019;17:399. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-02150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quiros PM, Goyal A, Jha P, Auwerx J. Analysis of mtDNA/nDNA ratio in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2017;7:47–54. doi: 10.1002/cpmo.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JI, Lee S-Y, Park M, Kim SY, Kim J-W, Kim SA, Kim B-N. Peripheral mitochondrial DNA copy number is increased in korean attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder patients. Front Psych. 2019;10:506. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartmann N, Reichwald K, Wittig I, Drose S, Schmeisser S, Luck C, Hahn C, Graf M, Gausmann U, Terzibasi E, Cellerino A, Ristow M, Brandt U, Platzer M, Englert C. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and function decrease with age in the short-lived fish Nothobranchius furzeri. Aging Cell. 2011;10:824–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little AC, Kovalenko I, Goo LE, Hong HS, Kerk SA, Yates JA, Purohit V, Lombard DB, Merajver SD, Lyssiotis CA. High-content fluorescence imaging with the metabolic flux assay reveals insights into mitochondrial properties and functions. Commun Biol. 2020;3:271. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0988-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt PR. The C. elegans model in toxicity testing. J Appl Toxicol. 2017;37:50–59. doi: 10.1002/jat.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baines RP, Wolton K, Thompson CRL. Dictyostelium discoideum: an alternative nonanimal model for developmental toxicity testing. Toxicol Sci. 2021;183:302–318. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfab097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee HY, Inselman AL, Kanungo J, Hansen DK. Alternative models in developmental toxicology. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2012;58:10–22. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2011.648302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang W, Chen J, Wang Z, Xie H, Hong H. Deep learning for predicting toxicity of chemicals: a mini review. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 2018;36:252–271. doi: 10.1080/10590501.2018.1537563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piersma AH. Alternative methods for developmental toxicity testing. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:427–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park SM, Jo NR, Lee B, Jung EM, Lee SD, Jeung EB. Establishment of a developmental neurotoxicity test by Sox1-GFP mouse embryonic stem cells. Reprod Toxicol. 2021;104:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung EM, Choi YU, Kang HS, Yang H, Hong EJ, An BS, Yang JY, Choi KH, Jeung EB. Evaluation of developmental toxicity using undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2015;35:205–218. doi: 10.1002/jat.3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong EJ, Choi Y, Yang H, Kang HY, Ahn C, Jeung EB. Establishment of a rapid drug screening system based on embryonic stem cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;39:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kornicka-Garbowska K, Bourebaba L, Rocken M, Marycz K. Inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase improves mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamics, reduces oxidative stress, and enhances adipogenic differentiation potential in metabolically impaired progenitor stem cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19:106. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00772-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seo BJ, Yoon SH, Do JT. Mitochondrial dynamics in stem cells and differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3893. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massart J, Borgne-Sanchez A, Fromenty B. Drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Cham: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallace KB, Sardão VA, Oliveira PJ. Mitochondrial determinants of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2020;126:926–941. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.119.314681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramachandran A, Jaeschke H. A mitochondrial journey through acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;140:111282. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caiment F, Wolters J, Smit E, Schrooders Y, Kleinjans J, van den Beucken T. Valproic acid promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in primary human hepatocytes in vitro; impact of C/EBPalpha-controlled gene expression. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94:3463–3473. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02835-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nazarewicz RR, Zenebe WJ, Parihar A, Larson SK, Alidema E, Choi J, Ghafourifar P. Tamoxifen induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial apoptosis via stimulating mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Can Res. 2007;67:1282–1290. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mansilla N, Racca S, Gras DE, Gonzalez DH, Welchen E. The complexity of mitochondrial complex IV: an update of cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:662. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng J, Ramirez VD. Inhibition of mitochondrial proton F0F1-ATPase/ATP synthase by polyphenolic phytochemicals. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1115–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Starke I, Glick GD, Börsch M. Visualizing mitochondrial FoF1-ATP synthase as the target of the immunomodulatory drug Bz-423. Front Physiol. 2018;9:803. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H, Chen H, Han S, Fu Y, Tian Y, Liu Y, Wang A, Hou H, Hu Q. Decreased mitochondrial DNA copy number in nerve cells and the hippocampus during nicotine exposure is mediated by autophagy. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;226:112831. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.