Abstract

Thioacetamide (TAA) was developed as a pesticide; however, it was soon found to cause hepatic and renal toxicity. To evaluate target organ interactions during hepatotoxicity, we compared gene expression profiles in the liver and kidney after TAA treatment. Sprague–Dawley rats were treated daily with oral TAA and then sacrificed, and their tissues were evaluated for acute toxicity (30 and 100 mg/kg bw/day), 7-day (15 and 50 mg/kg bw/day), and 4-week repeated-dose toxicity (10 and 30 mg/kg). After the 4-week repeated toxicity study, total RNA was extracted from the liver and kidneys, and microarray analysis was performed. Differentially expressed genes were selected based on fold change and significance, and gene functions were analyzed using ingenuity pathway analysis. Microarray analysis showed that significantly regulated genes were involved in liver hyperplasia, renal tubule injury, and kidney failure in the TAA-treated group. Commonly regulated genes in the liver or kidney were associated with xenobiotic metabolism, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress. We revealed changes in the molecular pathways of the target organs in response to TAA and provided information on candidate genes that can indicate TAA-induced toxicity. These results may help elucidate the underlying mechanisms of target organ interactions during TAA-induced hepatotoxicity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43188-022-00156-y.

Keywords: Thioacetamide, Hepatotoxicity, Nephrotoxicity, Oxidative stress, Oral toxicity

Introduction

Thioacetamide (TAA) is a thiono-sulfur-containing compound. It has been developed as a pesticide, fungicide, organic solvent, accelerator in the vulcanization of rubber, and stabilizer of motor oil [1–3]. However, TAA was first reported to be hepatotoxic by Fitzhugh and Nelson [4]. It is a typical hepatotoxin that causes centrilobular cell death accompanied by enhanced plasma transaminase and bilirubin levels. Acute exposure to TAA causes necrosis in the liver, whereas chronic exposure causes apoptosis in the liver [5, 6].

In animals, acute toxicity of TAA can result in centrilobular necrosis with a subsequent regenerative response, which can induce hepatotoxicity, including fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocarcinoma [6–10]. The advantages of TAA as a model hepatotoxin include its high specificity for the liver, regiospecificity for the perivenous area, and large time window between its necrogenic effects and liver failure [11, 12].

Understanding the role of TAA in nephrotoxicity is of great interest. Severe renal damage can be caused by environmental and industrial toxicants through the induction of highly reactive free radical generation [13]. TAA is one of the most extensively studied chemicals and industrial toxicants and is known to induce injury in the terminal portion of the proximal renal tubule [14]. After the administration of TAA, it undergoes extensive metabolism to form sulfoxide and sulfone, which circulate through various organs in the body before being transformed into acetate and excreted into urine within 24 h [15].

In this study, the toxicological properties of TAA were evaluated by toxicity assays to determine its single-dose acute toxicity (30 and 100 mg/kg bw/day), 7-day repeated-dose toxicity (15 and 50 mg/kg bw/day), and 4-week repeated-dose toxicity (10 and 30 mg/kg) in Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats following the guidelines of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The rats were treated daily with TAA and then sacrificed at 1 (6 and 24 h), 7, and 28 days after oral administration. The mortality rate, body weight, food consumption, and organ weight were measured and assessed. Ophthalmological, hematological, and histopathological parameters were evaluated. To evaluate target organ interactions during hepatotoxicity, we compared gene expression profiles in the liver and kidney after TAA treatment. Total RNA was extracted from the liver and kidneys, and microarray analysis was performed. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected based on fold changes and significance, and gene functions were analyzed using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA).

Materials and methods

Animals and drug treatment

Specific pathogen-free SD rats were obtained from Orient Bio Co., Ltd. (Seongnam-si, Gyunggi-do, Korea). The animals were housed under the following conditions: temperature, 23 ± 3 °C; relative humidity, 50 ± 10%; 12 h light/12 h dark cycle (turn on 08:00–20:00, 150–300 Lux); ventilation, 10–20 times/h, with ad libitum access to food (PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO, USA) and tap water. Five animals were kept in each cage for quarantine and acclimatization periods, and two animals per cage for the treatment period were maintained in a stainless wire cage (255 W × 465 L × 200 H mm). All personnel in the animal facility wore clothes, soft caps, masks, and gloves autoclaved under high pressure and steam (121 °C, 20 min). The experimental design was reviewed and approved by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Institute of Toxicology [approval no. 1303-0069 (acute study), 1303-0068 (7-day study), 1304-0101 (4-week study)] and conducted under the guidelines published by the OECD as well as GLP regulations for Nonclinical Laboratory Studies of Korea Food Drug Administration [16]. TAA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and diluted with distilled water (DW). The TAA suspension (administered to the highest-dosage group) was progressively diluted to prepare lower doses.

Experimental design for single oral dose toxicity study

For the single oral dose toxicity study, healthy male SD rats (6 weeks old) were randomly assigned to six groups (10 animals per group). Vehicle control (DW) or graded doses of TAA (30 and 100 mg/kg body weight) were administered to rats by oral gavage once at a dose of 10 mL/kg body weight. The rats were observed for mortality and clinical signs every hour for 1, 2, and 6 h after dosing during the first 24 h, and then once daily for 2 days. Body weights were recorded before the initiation of treatment and before necropsy. The animals were sacrificed at 6 and 24 h after the treatment by isoflurane (2–5%) inhalation, and their organs were collected for macroscopic necropsy examination. The weights of the liver, kidney, heart, testis, and lung were measured.

Experimental design for 7-day oral dose toxicity study

For the 7-day repeat-dose toxicity study, healthy male SD rats (6 weeks old) were randomly assigned to three groups (10 animals per group). Vehicle control (DW) or graded doses of TAA (15 and 50 mg/kg body weight) were administered to rats by oral gavage once daily for 7 days at a dose of 10 mL/kg body weight. The rats were observed daily for 7 days for mortality and clinical signs. Body weights were recorded on days 1, 3, and 7 after treatment. Animals were fasted overnight prior to necropsy. At study termination, all animals were euthanized by isoflurane (2–5%) inhalation, and their organs were collected for macroscopic necropsy examination. The weights of the liver, kidney, heart, testis, and lung were measured.

Experimental design for 4-week oral dose toxicity study

For the 4-week repeat-dose toxicity study, in accordance with OECD guideline 407 [17], healthy male SD rats (6 weeks old) were randomly assigned to three groups (10 animals per group). Vehicle control (DW) or graded doses of TAA (10 and 30 mg/kg body weight) were administered to rats by oral gavage once daily for 4 weeks at a dose of 10 mL/kg body weight. The rats were observed daily for clinical signs, including mortality, general appearance, and behavioral abnormalities, until terminal sacrifice. Body weight and food consumption were recorded weekly during the study period. At study termination, all animals were euthanized by the inhalation of isoflurane (2–5%) for blood sample collection.

Hematology and serum biochemical analysis

The rats were fasted overnight for scheduled collection. Blood samples were collected into EDTA-2K tubes by venipuncture of the posterior vena cava under isoflurane anesthesia. White blood cells, red blood cells, hemoglobin (HGB), hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelets (PLT), and differential WBC (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, leukocytes, and monocytes) were measured using the ADVIA120 Hematology System (Bayer, USA). Blood samples collected in tubes without anticoagulants were maintained at room temperature and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for approximately 10 min on the day of necropsy. The serum biochemical parameters examined included glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (CREA), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), albumin/globulin ratio (A/G), total cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), phospholipid (PL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin (TBIL), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), creatine phosphokinase (CK), gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), inorganic phosphorus (IP), calcium, chloride, sodium, and potassium. These were measured automatically using a TBA 200FR NEO (Toshiba Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Gross findings, organ weights and histopathological examination

Animals were fasted overnight prior to necropsy. Isoflurane was administered intravenously, followed by exsanguination after blood collection for hematology and serum biochemistry. During necropsy, macroscopic examination of all the tissues was performed and tissue samples were collected from all rats. The liver, heart, kidney, testis, and lung were weighed, relative organ weights were presented as percentages of body weight, and organs were preserved in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin. All preserved tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined under a microscope (BX53; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded kidney tissues were dewaxed with xylene and graded alcohol series (100, 95, 70, and 50%). The tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then placed in an antigen retrieval solution and permeabilized with PBS containing Tween-20 (PBST, 1%). After blocking with 5% (v/v) bovine serum albumin in PBST (0.01%), the tissues were incubated overnight with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against KIM-1 at 4 °C. The tissues were then incubated with affinity-purified Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and mounted with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole mounting medium. Finally, images were captured using an inverted phase-contrast fluorescence microscope (IX51, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

RNA extraction and microarray analysis

At necropsy, the entire right kidney and liver were extracted and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. The frozen samples were homogenized with a tissuelyser (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and total RNA was purified using an RNase® Mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The concentration and quality of the total RNA were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and RNA integrity was measured using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The Affymetrix GeneChip Rat 230 2.0 (Affymetrix, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for microarray analysis and scanned using the GeneChip® 3 expression array user guide (Affymetrix, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The biofunctions and canonical pathways of the DEGs were analyzed using IPA software (version 9.0, Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA, USA) as previously described [18]. We selected pathways and gene lists based on the biofunctions and canonical pathways generated through the ingenuity systems knowledge base using right-tailed Fisher’s exact test.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

The gene expression results from the microarray analysis were validated using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Gene-specific primers were purchased from Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea). Total RNA (2 μg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and oligo-dT primers, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed in a 20 μL reaction volume containing 0.5 μL (5 pM) each of the forward and reverse primers, 10 μL of SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 2 μL of cDNA, and 7 μL of nuclease-free water. cDNA was amplified using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences were as follows: cytochrome p450 (CYP) 1A2, forward 5'-ATGCTCTTCGGCTTGGGAAA-3' and reverse TGAACTCCAGCTGATGCAGG; CYP2B6, forward 5'-AGGACCATGGAGCCCAGTAT-3' and reverse 5'-AGAAATCCTCAGCTTGGCCC-3'; CYP2C9, forward 5'-CGCACGGAGCTGTTTTTGTT-3' and reverse 5'-AGAGAGTCTGCCCTTTGCAC-3'; CYP2D6, forward 5'-CCAGGGCAACTTTGTGAAGC-3' and reverse 5'-GTAGGGGGAAGGGCTAAGGA-3'; ALDH1A1, forward 5'-CGTCTCCTATCGTCACCAGC-3' and reverse 5'-ATCACGACTGGTCCTCCTCA-3'; SULT2A1, forward 5'-CCATGCGAGAATGGGACAAC-3' and reverse 5'-AGTCCCCAATAGTGCCTTTCC-3'; UGT2B4, forward 5'-AAGGCTGTGATCTGTGGTCG-3' and reverse 5'-AGCAAGTTGGTGTTTCAGGGA-3'; UGT2B17, forward 5'-AGCAGAGCCCTGAGAGATGA-3' and reverse 5'-GTTGGGCAAAGCTTCTCAGC-3'; ABCC2, forward 5'-GGGCTGTGCTTCGAAAATCC-3' and reverse 5'-CCTGTGAGCGATGGTGATGA-3'; ABCC3, forward 5'-AGATGCAGGACTCGCCTAGA-3' and reverse 5'-TCCAAGGACCCACTTCCTCA-3'; Glutathione S-transferase A3 (GSTA3), forward 5'-GCCATGGCCAAGACTACCTT-3' and reverse 5'-TGCAAAACATCAGAGCCTGGA-3'; NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NQO1), forward 5'-TCAGGTGGCCTGGGATATGA-3' and reverse 5'-CCTCCTGCCCTAAACCACAG-3'; HAVCR1 (Kim1), forward 5'-GGCACACATCAGGGGAAGAA-3' and reverse 5'-AACCCGTGGTAGTCCCAAAC-3'; RGN, forward 5'-TGCTCTGGGGCTTGAAATGA-3' and reverse 5'-ACCACAGTTTGTGCTCCAGT-3'; SLC22A2 (Oct2), forward 5'-CAGGGACCATGTCGACCG-3' and reverse 5'-TCATACCTCATGCACTGGCTG-3'; Slco1a1 (Oatp), forward 5'-CAGGCACATTTACCTGGGGT-3' and reverse 5'-TCAGGATTCCGAGGAAGGGA-3'.

The mRNA levels of the target genes were normalized to the metabolism, oxidative stress, and renal toxicity biomarker expression levels, and the results were expressed as fold change relative to the normal control group.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using multiple comparison methods. When Bartlett’s test showed no significant deviations from variance homogeneity, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if any of the group means differed at a significance level of p < 0.05. Dunnett’s test was used to determine differences in data between the control and treatment groups when the data were found to be significant from the ANOVA test. Furthermore, when significant deviations from variance homogeneity were observed in Bartlett’s test, a non-parametric comparison test, the Kruskal–Wallis (H) test, was conducted to determine if any of the group means differed at p < 0.05. When a significant difference was observed in the Kruskal–Wallis (H) test, Dunn’s Rank Sum test was conducted to quantify the specific pairs of group data that were significantly different from the mean. Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare pairs of data (including prevalence and percentage). The level of probability was set at 1 or 5%. Statistical analyses were performed by comparing the data from the different treatment groups with those from the control group using Path/Tox (version. 4.2.2, Xybion Medical Systems Corporation, USA).

Results

Single oral dose toxicity study

In the 6 and 24 h observation of acute toxicity study using rats following a single oral administration of TAA at 30 and 100 mg/kg, the findings were as follows:

There were no significant changes in clinical signs, mortality, body weight, urinalysis, hematological parameters, or macroscopic necropsy in rats following the administration of TAA (data not shown).

TAA treatment significantly increased the proportion of BUN, CREA, AST, ALT, and TBIL in rats at a dose of 100 mg/kg 6 and 24 h after sacrifice (Table S1).

The absolute and relative weights of the liver in male rats significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner compared to those in the control group. The absolute weights of the kidneys in male rats significantly decreased at 30 mg/kg bw/day after 24 h of sacrifice (Tables S2, S3).

Histopathological findings related to TAA treatment were observed in the liver and kidneys (Table S4). Proximal tubule hypertrophy was observed in the kidneys of males administered 100 mg/kg bw/day after 24 h of sacrifice. In the liver, centrilobular mononuclear infiltration, bile duct neutrophil infiltration, centrilobular single-cell necrosis, and centrilobular hepatocyte vacuolar degeneration were observed in males administered 30 and 100 mg/kg bw/day after 6 and 24 h of sacrifice.

7-day repeat-dose oral toxicity study

Repeated administration of TAA at 15 and 50 mg/kg bw/day by gavage for 7 days caused side effects.

Abnormal clinical signs, such as fur loss, were observed in TAA-treated rats. The body weight of the animals administered 15 and 50 mg/kg bw/day of TAA significantly decreased from 3 days to between 78 and 92% by 7 days compared with the body weight of controls (Table S5).

TAA treatment at a dose of 50 mg/kg significantly increased the proportion of BUN, ALT, and TBIL in male rats (Table S6).

The relative weights of the liver and kidneys in male rats significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner compared to those in the control group (Tables S7, S8).

Histopathological findings related to TAA treatment were observed in the liver and kidneys (Table S9). In the kidneys, casts, tubule dilatation, interstitial fibrosis, and proximal tubule vacuolation were observed in male rats administered 15 and 50 mg/kg bw/day. In the liver, centrilobular mononuclear infiltration, centrilobular fibrosis, and centrilobular single-cell necrosis were observed in male rats administered 15 and 50 mg/kg bw/day. Of the two TAA concentrations tested, 30 mg/kg bw/day was selected as the highest dose for the 4-week repeat-dose oral toxicity study.

4-week repeat-dose oral toxicity study

Mortality and clinical observations

No treatment-related mortality was observed in any of the study groups during the 4-week repeated dose toxicity study. TAA induced the loss of fur in one male rat at 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day. However, no histopathological correlations were observed. The changes in body weight during the treatment period are shown in Table 1. The body weight of the animals administered 10 mg/kg bw/day of TAA significantly decreased to 92% in 28 days compared with the body weight of controls. The body weight of the animals administered 30 mg/kg bw/day of TAA significantly decreased from 9 days to between 79 and 85% in 28 days compared with the body weight of controls.

Table 1.

Body weights and weight gains at 29 days after treating rats with 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Unit (g) | Body weights | Weights gains | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day | Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day | |

| Day 1 | 210.8 ± 4.97 | 210.4 ± 9.24 | 211.0 ± 7.57 | – | – | – |

| Day 9 | 271.0 ± 10.75 | 261.4 ± 13.55 | 232.9 ± 8.39** | 60.2 ± 7.58 | 51.1 ± 6.91** | 22.0 ± 5.38** |

| Day 15 | 315.1 ± 14.05 | 300.9 ± 21.44 | 267.8 ± 13.84** | 104.3 ± 11.06 | 90.5 ± 16.21* | 56.9 ± 8.42** |

| Day 22 | 356.8 ± 18.14 | 336.4 ± 28.71 | 291.8 ± 18.59** | 146.0 ± 15.61 | 126.1 ± 23.98* | 80.8 ± 12.59** |

| Day 28 | 385.2 ± 18.69 | 356.1 ± 33.27* | 307.7 ± 23.19** | 174.4 ± 16.08 | 145.7 ± 28.92* | 96.8 ± 16.80** |

*Significant differences from control group (p < 0.05)

**Significant differences from control group (p < 0.01)

Hematology and serum biochemistry

Hematology results showed that most hematological parameters were not significantly altered by TAA treatment, except for HGB, HCT, MCV, MCH, MCHC, and differential WBC counts (neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes) in certain groups (Table 2). However, these values remained within the normal range [19, 20].

Table 2.

Hematological parameters at 29 days after treating rats with 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Unit | Dose | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day | ||

| WBC | (× 10^3/µL) | 10.33 ± 2.754 | 10.09 ± 1.351 | 10.55 ± 2.115 |

| RBC | (× 10^6/µL) | 8.56 ± 0.373 | 8.72 ± 0.504 | 8.42 ± 0.405 |

| HGB | (g/dL) | 16.5 ± 0.58 | 16.2 ± 0.95 | 15.5 ± 0.63** |

| HCT | (%) | 51.7 ± 1.80 | 50.5 ± 2.75 | 47.4 ± 1.73** |

| MCV | (fL) | 60.4 ± 1.28 | 58.0 ± 1.47** | 56.3 ± 1.24** |

| MCH | (pg) | 19.3 ± 0.41 | 18.6 ± 0.44** | 18.4 ± 0.43** |

| MCHC | (g/dL) | 32.0 ± 0.52 | 32.1 ± 0.43 | 32.6 ± 0.41** |

| PLT | (10^3/µL) | 1197 ± 142.2 | 1255 ± 133.9 | 1361 ± 154.9 |

| RET | (%) | 2.91 ± 0.364 | 3.03 ± 0.676 | 3.46 ± 0.791 |

| RETA | (10^9/L) | 248.5 ± 26.77 | 261.5 ± 42.87 | 289.1 ± 59.69 |

| NEU | (%) | 11.1 ± 3.41 | 10.8 ± 2.61 | 14.6 ± 3.26* |

| LYM | (%) | 84.2 ± 3.95 | 84.7 ± 2.28 | 78.8 ± 3.63** |

| EOS | (%) | 0.7 ± 0.39 | 0.8 ± 0.16 | 0.7 ± 0.28 |

| MON | (%) | 2.3 ± 0.69 | 2.3 ± 0.73 | 4.1 ± 1.06** |

| BAS | (%) | 0.5 ± 0.18 | 0.5 ± 0.12 | 0.4 ± 0.09 |

| LUC | (%) | 1.1 ± 0.29 | 1.0 ± 0.34 | 1.4 ± 0.47 |

*Significant differences from control group (p < 0.05)

**Significant differences from control group (p < 0.01)

Serum biochemistry results showed that TAA treatment significantly increased the proportion of ALT, TBIL, ALP, and GGT in male rats at a dose of 30 mg/kg (Table 3).

Table 3.

Serum biochemical parameters at 29 days after treating rats with 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Unit | Dose | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day | ||

| GLU | (mg/dL) | 108.4 ± 25.28 | 97.2 ± 18.38 | 98.0 ± 14.39 |

| BUN | (mg/dL) | 13.0 ± 1.29 | 12.2 ± 1.86 | 11.7 ± 1.30 |

| CREA | (mg/dL) | 0.52 ± 0.0.033 | 0.53 ± 0.040 | 0.52 ± 0.063 |

| TP | (g/dL) | 6.56 ± 0.201 | 6.68 ± 0.221 | 6.38 ± 0.248 |

| ALB | (g/dL) | 4.35 ± 0.102 | 4.60 ± 0.098** | 4.46 ± 0.121 |

| A/G | (Ratio) | 1.98 ± 0.115 | 2.22 ± 0.116** | 2.32 ± 0.158** |

| TCHO | (mg/dL) | 57.0 ± 15.76 | 41.3 ± 7.65* | 60.0 ± 15.47 |

| TG | (mg/dL) | 44.9 ± 16.65 | 36.2 ± 5.70 | 44.0 ± 9.48 |

| PL | (mg/dL) | 88 ± 18.6 | 74 ± 8.6 | 105 ± 17.3* |

| AST | (IU/L) | 116.9 ± 18.49 | 116.3 ± 12.93 | 155.6 ± 29.10** |

| ALT | (IU/L) | 30.4 ± 4.17 | 26.6 ± 4.86 | 34.1 ± 6.38 |

| TBIL | (mg/dL) | 0.099 ± 0.0082 | 0.139 ± 0.0241* | 0.259 ± 0.0359** |

| ALP | (IU/L) | 501.8 ± 59.46 | 521.4 ± 100.23 | 632.3 ± 110.48** |

| CK | (IU/L) | 582 ± 158.4 | 586 ± 117.4 | 740 ± 247.4 |

| Ca | (mg/dL) | 11.08 ± 0.325 | 11.79 ± 0.272** | 11.80 ± 0.444** |

| IP | (mg/dL) | 10.78 ± 0.385 | 11.06 ± 0.635 | 11.55 ± 0.760* |

| Na | (mmol/L) | 143 ± 1.3 | 144 ± 1.3 | 143 ± 1.6 |

| K | (mmol/L) | 8.72 ± 0.793 | 8.15 ± 0.642 | 8.07 ± 0.744 |

| Cl | (mmol/L) | 100 ± 1.3 | 101 ± 0.9* | 101 ± 1.3* |

| GGT | (IU/L) | 0.05 ± 0.161 | 0.14 ± 0.252 | 0.67 ± 1.071 |

*Significant differences from control group (p < 0.05)

**Significant differences from control group (p < 0.01)

Other statistically significant changes were not considered treatment-related, as they were not dose-dependent and the magnitude of the changes was minimal.

Gross findings and organ weight measurement

The relative weights of the liver and kidneys in male rats significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner compared to those in the control group (Tables 4, 5). In addition, no treatment-related gross findings were observed during necropsy in any of the rats.

Table 4.

Absolute organ weights at 29 days after treating rats with 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Unit (g) | Dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day | |

| Liver | 12.021 ± 0.8394 | 12.075 ± 1.0046 | 11.871 ± 0.8900 |

| Kidneys | 3.061 ± 0.1390 | 2.798 ± 0.2882* | 2.641 ± 0.2041** |

| Heart | 1.281 ± 0.1146 | 1.196 ± 0.1211 | 1.021 ± 0.0999** |

| Lung | 1.547 ± 0.1391 | 1.541 ± 0.1220 | 1.332 ± 0.0923** |

| Testis | 3.018 ± 0.1019 | 3.016 ± 0.3986 | 3.031 ± 0.1850 |

*Significant differences from control group (p < 0.05)

**Significant differences from control group (p < 0.01)

Table 5.

Relative organ weights at 29 days after treating rats with 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Unit (%) | Dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day | |

| Liver | 3.387 ± 0.2653 | 3.700 ± 0.2162** | 4.269 ± 0.1686** |

| Kidneys | 0.862 ± 0.0464 | 0.856 ± 0.0440 | 0.950 ± 0.0531** |

| Heart | 0.360 ± 0.0200 | 0.366 ± 0.0204 | 0.367 ± 0.0274 |

| Lung | 0.435 ± 0.0359 | 0.474 ± 0.0507 | 0.480 ± 0.0334* |

| Testis | 0.851 ± 0.0487 | 0.925 ± 0.1249 | 1.093 ± 0.0772** |

*Significant differences from control group (p < 0.05)

**Significant differences from control group (p < 0.01)

Microscopic Observations and immunohistochemistry changes

Histopathological findings showed treatment-related changes in the TAA-treated animals (Table 6). In the liver, bile duct hyperplasia, centrilobular mononuclear infiltration, and centrilobular single-cell necrosis were observed in males administered 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day.

Table 6.

Histopathological findings at 29 days after treating rats with 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Dose | Control | 10 mg/kg/day | 30 mg/kg/day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number Examined | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Kidneys | |||

| Basophilia, Proximal tubule | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Cast | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cyst | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Inflammatory cell foci | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Liver | |||

| Bile duct hyperplasia | 0 | 3 | 10 |

| Cellular infiltration, inflammatory | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| Change, eosinophilic, hepatocyte, centrilobular | 0 | 4 | 10 |

| Focal necrosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Infiltration, mononuclear, centrilobular | 0 | 8 | 10 |

| Pigmented macrophages, centrilobular | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Prominent nucleoli, hepatocyte, centrilobular | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Single cell necrosis, centrilobular | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Tension lipidosis | 2 | 1 | 3 |

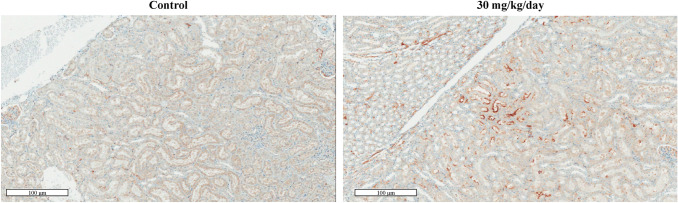

In the kidneys, cast and proximal tubule basophilia were observed in males administered 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day, respectively. Additionally, distinct immunohistochemical Kim-1 expression was observed in several tubular cells treated with 30 mg/kg bw/day (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Histopathological changes in the kidney after 4-week consecutive thioacetamide (TAA; 30 mg/kg) administration. The kidney section from 30 mg/kg bw/day-treated group was found to have evidently increased KIM-1 expression level in the tubular area when compared with that from the control group

Global gene expression analysis

To evaluate the target organ interactions during TAA-induced hepatotoxicity, gene expression profiling was performed in three organs after 28 days of TAA administration. A total of 3868 and 1281 genes were differentially expressed in the liver and kidney, respectively, based on 1.5 fold changes and statistical significance (p < 0.05) (Tables 7, 8). In the liver, 1,058 genes were differentially expressed at 10 mg/kg bw/day and 3554 genes at 30 mg/kg bw/day. In the 10 mg/kg bw/day group, 669 genes were upregulated and 389 genes were downregulated. In the 30 mg/kg bw/day group, 2223 genes were upregulated and 1331 genes were downregulated. In the kidneys, 369 genes were differentially expressed at 10 mg/kg bw/day and 1054 genes at 30 mg/kg bw/day. In the 10 mg/kg bw/day group, 149 genes were upregulated and 220 genes were downregulated. In the 30 mg/kg bw/day group, 544 genes were upregulated and 510 genes were downregulated. In the 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day-treated group, the common number of regulated genes between the liver or the kidney were upregulated in 178 genes and downregulated in 110 genes (Fig. 2).

Table 7.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at 29 days after treating rats with 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| X1.5 & 0.05 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose ( mg/kg) | Up | Down | All | ||

| Liver | 10 | 669 | 389 | 1058 | 3868 |

| 30 | 2223 | 1331 | 3554 | ||

| Kidneys | 10 | 149 | 220 | 369 | 1281 |

| 30 | 544 | 510 | 1054 | ||

Table 8.

Tox function analysis results at 29 days after treating rats with 30 mg/kg bw/day thioacetamide (TAA)

| Category | p value | No. of genes |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Gene Profiles | ||

| Liver Hyperplasia/Hyperproliferation | 5.83E-08–3.61E-01 | 72 |

| Liver Proliferation | 2.48E-05–2.27E-01 | 32 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.98E-04–3.61E-01 | 47 |

| Liver Hyperbilirubinemia | 5.57E-04–8.23E-02 | 3 |

| Liver Hemorrhaging | 6.23E-04–8.23E-02 | 8 |

| Liver Necrosis/Cell Death | 1.47E-03–3.22E-01 | 32 |

| Renal Gene Profiles | ||

| Renal Damage | 6.37E-06–2.71E-01 | 16 |

| Renal Tubule Injury | 6.37E-06–2.15E-01 | 12 |

| Renal Necrosis/Cell Death | 1.7E-04–1E00 | 16 |

| Renal Dysplasia | 1.98E-03–1.98E-03 | 9 |

| Kidney Failure | 2E-03–2E-01 | 2 |

Fig. 2.

Common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and comparison of two organ profiling after treating rats with thioacetamide (TAA) at 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day. a Overlap between upregulated or downregulated genes in the liver and kidney. b Pathway analysis of overlap between DEGs. c Comparison of tox list analysis of two organs (the liver and kidney). d Canonical pathway analysis associated with the liver and kidney

Functional analysis of DEGs showed that genes related to xenobiotic metabolism and lipid metabolism were commonly regulated in two organs. Constitutive androstane receptor (CAR)/retinoid X receptor (RXR) activation and Pregnane X receptor (PXR)/RXR activation were detected as the relevant canonical pathways in both organs (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2).

Significantly regulated genes in each target organ were selected and the transcriptional level was validated by real-time PCR. The mRNA levels of metabolism-related genes, oxidative stress, and renal toxicity biomarkers were assessed in fresh tissues using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Common regulated genes in the liver and kidney and the expression levels of CYP2C9 were inhibited by both doses of TAA. At 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day of TAA, the expression levels of UGT2B4, ABCC2, ABCC3, and NQO1 were activated (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Thioacetamide (TAA)-induced differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and the expression of regulators in the liver and kidney were confirmed using the real time rt-PCR analysis. The results showed that selected genes were deregulated in a dose-dependent manner

Discussion

Although TAA was developed as a pesticide, it was soon found to cause hepatic and renal toxicity. TAA is a well-known chemical that induces hepatotoxicity, including fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cancer, and has been used to establish animal models to investigate human chronic hepatic disease [21–24]. It has been widely used in animal studies, largely because of its ability to cause acute liver and kidney damage and cancer in animal models, and TAA disease models have been used to investigate chronic hepatic disease in humans [25–27].

To explore the TAA toxicity profiles and determine adequate doses for repeated exposure toxicity studies, a TAA acute toxicity study was performed. In the acute toxicity tests, there were no evident TAA dose-related changes in clinical signs or mortality. However, dose-dependent hepatotoxicity was observed, especially in the 30 mg/kg TAA-treated group, which was confirmed by elevated serum liver enzyme levels and histopathological changes, including centrilobular hepatocyte degeneration, mononuclear cell infiltration and hepatocyte necrosis.

After the acute toxicity study, a 7-day repeated-dose toxicity study was conducted as a preliminary study for a 4-week repeated-dose toxicity study. In this study, although evident body weight loss was observed after TAA administration, no prominent serum indices for hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity were detected. When considering the dose and exposure periods, the present relatively decreased serum liver enzyme levels after 7-day of repeated TAA administration then single exposure might be due to the activated systemic defense or adaptation against repeated TAA treatment, which was supported by gradually increased weight gains. Considering the above meaningful results in the acute and 7-day repeat-dose oral toxicity studies, 30 mg/kg was selected as the highest dose of TAA for the 4-week repeated-dose toxicity study.

In the 4-week toxicity study, repeated administration of TAA at doses of up to 30 mg/kg did not cause abnormal alterations in mortality or behavioral symptoms as early signs of toxicity. Rats treated with TAA showed dose-associated differences in body weight, indicating that TAA retarded animal growth or normal metabolism. Along with changes in serum biochemical parameters (TBIL, ALT, ALP, and GGT) and organ weights (liver and kidneys), the histopathological findings supported our conclusion that hepatotoxicity and renal toxicity could be attributed to TAA treatment.

Comprehensive organ toxicological studies are more helpful in understanding the systemic effects of toxic substances than toxicity studies that target specific organs. The liver and kidneys are the major organs involved in the metabolism, elimination, and detoxification of drugs and other foreign compounds [28]. They can be considered major target organs that suffer systemic adverse reactions following oral administration of drugs [29–31]. Microarray analysis was conducted to determine the potential genes involved in the pathological changes in the liver and kidney after 28 days of TAA treatment. Previously, acute TAA toxicity induced gene expression in liver, kidney, and heart tissues and elevated inflammatory responses and cell death-related gene expression after TAA treatment [32]. In the present study, a total of 3868 and 1281 genes were differentially expressed in the liver and kidney, respectively, and 288 genes were selected as commonly changed genes between the two organs. Functional analysis of DEGs showed that genes related to xenobiotic metabolism, oxidative stress, and lipid metabolism were commonly regulated in the liver and kidneys. In the tox list analysis, CAR/RXR activation-related genes were mostly altered in both the liver and kidney after TAA treatment, followed by xenobiotic metabolic signaling. CAR, PXR, and RXR are nuclear receptor families that regulate cholesterol, lipids, glucose, and xenobiotic metabolism [33]. The altered CAR/RXR and PXR/RXR genes might be responsible for the elevated serum TBIL levels observed in the 28 days TAA toxicity study.

Since xenobiotic metabolism was one of the relevant signals from both canonical pathways and Tox list analysis, genes involved in xenobiotic metabolism were selected and expression patterns were validated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

In the liver, the expression of most phase 1 metabolism-related genes was inhibited. CYP is an enzyme mainly found in the liver endoplasmic reticulum, and the TAA intermediate metabolite covalently binds to hepatic macromolecules, leading to cellular damage [34]. The decrease in CYP might be due to compromised hepatocytes by TAA-derived hepatocyte necrosis. In contrast to the phase 1 metabolism-related gene expression pattern, genes related to phase II metabolism and transporters were enhanced in a dose-dependent manner. Although the exact reason remains unclear, altered activities of several xenobiotic conjugation enzymes and transporters have been reported in liver disease conditions [35]. In the kidney, drug metabolism-related gene expression patterns were comparable to those in the liver. Caution is warranted as the pharmacokinetic behavior of several therapeutics may be altered by TAA intoxication.

Additional commonly regulated oxidative stress-related genes in the liver and kidneys were assessed. In the present study, GSTA3 and NQO1 expression levels were enhanced in a dose-dependent manner. GSTA3 encodes Glutathione S-transferases, which are potent detoxification enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of glutathione to electrophilic compounds [36]. NQO1 is a ubiquitous electron reductase responsible for the detoxification and activation of quinones [37]. Oxidative stress, one of the factors responsible for the toxic mechanism of TAA, presents dose-dependent increases in GSTA3 and NQO1 expression levels that could be induced to counter TAA organ damage in both the liver and kidney.

In conclusion, we suggest simultaneous regulation of genes at the transcriptional level in the liver and kidneys when hepatotoxicity is induced by TAA, which may provide clues for understanding the underlying molecular mechanism of organ interaction during TAA hepatotoxicity. Further studies are needed to elucidate systemic TAA toxicity following sequential TAA treatment and integrative transcriptome analysis of target organ interactions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary figure 1. Tox list analysis of two organs (the liver and kidney) after 4-week consecutive thioacetamide (TAA; 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day). Supplementary figure 2. Top regulated canonical pathways in the liver and kidney after the 4-week consecutive thioacetamide (TAA; 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day) treatment. Supplementary file2 (PPTX 1083 KB)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2020R1F1A1054226, NRF-2021M3A9H3016047 and NRF-2015M3A7B6027948), a grant from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2021 (21162MFDS045), research fund of Chungnam National University, and the Korea Institute of Toxicology (KIT) Research Program (No. 1711159817).

Funding

Korea Institute of Toxicology, No. 1711159817, Hyoung-Yun Han.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Hyoung-Yun Han and Se-Myo Park have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jung-Hwa Oh, Email: jhoh@kitox.re.kr.

Sang Kyum Kim, Email: sangkim@cnu.ac.kr.

Tae-Won Kim, Email: taewonkim@cnu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Lee JW, Shin KD, Lee M, Kim EJ, Han SS, Han MY, Ha H, Jeong TC, Koh WS. Role of metabolism by flavin-containing monooxygenase in thioacetamide-induced immunosuppression. Toxicol Lett. 2003;136:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schyman P, Printz RL, Estes SK, O’Brien TP, Shiota M, Wallqvist A. Assessing chemical-induced liver injury in vivo from in vitro gene expression data in the rat: the case of thioacetamide toxicity. Front Genet. 2019;10:1233. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staňková P, Kučera O, Lotková H, Roušar T, Endlicher R, Cervinková Z. The toxic effect of thioacetamide on rat liver in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24(8):2097–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzhugh OG, Nelson AA. Chronic oral toxicity of alpha-naphthyl thiourea. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1947;64:305–310. doi: 10.3181/00379727-64-15776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S, Sarkar A, Bhattacharyya S, Sil PC. Silymarin protects mouse liver and kidney from thioacetamide induced toxicity by scavenging reactive oxygen species and activating PI3K-Akt pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:481. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreira E, Fontana L, Periago JL, Sanchéz De Medina F, Gil A. Changes in fatty acid composition of plasma, liver microsomes, and erythrocytes in liver cirrhosis induced by oral intake of thioacetamide in rats. Hepatology. 1995;21(1):199–206. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low TY, Leow CK, Salto-Tellez M, Chung MC. A proteomic analysis of thioacetamide-induced hepatotoxicity and cirrhosis in rat livers. Proteomics. 2004;4(12):3960–3974. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangipudy RS, Chanda S, Mehendale HM. Tissue repair response as a function of dose in thioacetamide hepatotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(3):260–267. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natarajan SK, Thomas S, Ramamoorthy P, Basivireddy J, Pulimood AB, Ramachandran A, Balasubramanian KA. Oxidative stress in the development of liver cirrhosis: a comparison of two different experimental models. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(6):947–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuyama H, Nakamura H, Shimahara Y, Araya S, Kawada N, Yamaoka Y, Yodoi J. Overexpression of thioredoxin prevents acute hepatitis caused by thioacetamide or lipopolysaccharide in mice. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):1015–1025. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilakapati J, Shankar K, Korrapati MC, Hill RA, Mehendale HM. Saturation toxicokinetics of thioacetamide: role in initiation of liver injury. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(12):1877–1885. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehendale HM. Tissue repair: an important determinant of final outcome of toxicant-induced injury. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33(1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/01926230590881808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansil PN, Nitha A, Prabha SP, Wills PJ, Jazaira V, Latha MS. Protective effect of Amorphophallus campanulatus (Roxb.). Blume tuber against thioacetamideinduced oxidative stress in rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4(11):870–877. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begum Q, Noori S, Mahboob T. Antioxidant effect of sodium selenite on thioacetamide-induced renal toxicity. Pak J Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;44:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Negishi K, Noiri E, Maeda R, Portilla D, Sugaya T, Fujita T. Renal L-type fatty acid-binding protein mediates the bezafibrate reduction of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2008;73(12):1374–1384. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.KFDA (2012) Good laboratory practice regulation for non-clinical laboratory studies (Notification No. 2012-61)

- 17.OECD (1998) OECD Guideline for testing of chemicals, Test No 407: Repeated dose 28-day oral toxicity study in rodents. 10.1787/20745788.

- 18.Son MY, Kim YD, Seol B, Lee MO, Na HJ, Yoo B, Chang JS, Cho YS. Biomarker discovery by modeling Behcet’s disease with patient-specific human induced Pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26(2):133–145. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derelanko MJ, Auletta CS. Handbook of toxicology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han ZZ, Xu HD, Kim KH, Ahn T, Bae J, Lee J, Gil K, Lee J, Woo S, Yoo H, Lee H, Kim K, Park C, Zhang H, Song S. Reference data of the main physiological parameters in control Sprague-Dawley rats from pre-clinical toxicity studies. Lab Anim Res. 2010;26(2):153–164. doi: 10.5625/lar.2010.26.2.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delire B, Stärkel P, Leclercq I. Animal models for fibrotic liver diseases: what we have, what we need, and what is under development. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015;3(1):53–66. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reif S, Aeed H, Shilo Y, Reich R, Kloog Y, Kweon YO, Bruck R. Treatment of thioacetamide-induced liver cirrhosis by the Ras antagonist, farnesylthiosalicylic acid. J Hepatol. 2004;41(2):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salguero Palacios R, Roderfeld M, Hemmann S, Rath T, Atanasova S, Tschuschner A, Gressner OA, Weiskirchen R, Graf J, Roeb E. Activation of hepatic stellate cells is associated with cytokine expression in thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis in mice. Lab Investig. 2008;88(11):1192–1203. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starkel P, Leclercq IA. Animal models for the study of hepatic fibrosis. Best Pract. Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(2):319–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Benjamin IS, Alexander B. Reproducible production of thioacetamide-induced macronodular cirrhosis in the rat with no mortality. J Hepatol. 2002;36(4):488–493. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang JM, Han DW, Xie CM, Liang QC, Zhao YC, Ma XH. Endotoxins enhance hepatocarcinogenesis induced by oral intake of thioacetamide in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4(2):128–132. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh CN, Maitra A, Lee KF, Jan YY, Chen MF. Thioacetamide-induced intestinal-type cholangiocarcinoma in rat: an animal model recapitulating the multi-stage progression of human cholangiocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(4):631–636. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mroueh M, Saab Y, Rizkallah R. Hepatoprotective activity of Centaurium erythraea on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Phytother Res. 2004;18(5):431–433. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han H, Han K, Ahn J, Park S, Kim S, Lee B, Min B, Yoon S, Oh J, Kim T. Subchronic toxicity assessment of Phytolacca americana L. (Phytolaccaceae) in F344 rats. Nat Prod Commun. 2020;15:1–10. doi: 10.1177/1934578X20941656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim KT, Lim V, Chin JH. Subacute oral toxicity study of ethanolic leaves extracts of Strobilanthes crispus in rats. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(12):948–952. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worasuttayangkurn L, Watcharasit P, Rangkadilok N, Suntararuks S, Khamkong P, Satayavivad J. Safety evaluation of longan seed extract: acute and repeated oral administration. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50(11):3949–3955. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schyman P, Printz RL, Estes SK, Boyd KL, Shiota M, Wallqvist A. Identification of the toxicity pathways associated with thioacetamide-induced injuries in rat liver and kidney. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1272. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daujat-Chavanieu M, Gerbal-Chaloin S. Regulation of CAR and PXR expression in health and disease. Cells. 2020;9(11):2395. doi: 10.3390/cells9112395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Meyer C, Xu C, Weng H, Hellerbrand C, Dijke P, Dooley S. Animal models of chronic liver diseases. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304(5):449–468. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00199.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang F, Miao MX, Sun BB, Wang ZJ, Tang XG, Chen Y, Zhao KJ, Liu XD, Liu L. Acute liver failure enhances oral plasma exposure of zidovudine in rats by downregulation of hepatic UGT2B7 and intestinal P-gp. Acta Pharmacol Sinica. 2017;38(11):1554–1565. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIlwain CC, Townsend DM, Tew KD. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms: cancer incidence and therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25(11):1639–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang K, Chen D, Ma K, Wu X, Hao H, Jiang S. NAD (P) H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) as a therapeutic and diagnostic target in cancer. J Med Chem. 2018;61(16):6983–7003. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figure 1. Tox list analysis of two organs (the liver and kidney) after 4-week consecutive thioacetamide (TAA; 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day). Supplementary figure 2. Top regulated canonical pathways in the liver and kidney after the 4-week consecutive thioacetamide (TAA; 10 and 30 mg/kg bw/day) treatment. Supplementary file2 (PPTX 1083 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.