Abstract

We present herein our results of cricoid augmentation with costal cartilage in complex crico-tracheal stenosis in adults. This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained data of patients who underwent surgery for crico-tracheal stenosis at a tertiary care centre from March 2012 to September 2019. Finding of subglottic stenosis with cricoid narrowing was taken as an indication for cricoid split and costal cartilage graft augmentation. Their demographic and clinical data, pre-operative work up, intra-operative details and post-operative course was recorded. Ten patients underwent cricoid split with costal cartilage graft augmentation and crico-tracheal anastomosis between March 2012 and November 2019. The mean age was 29 years (range, 22–58 years). There were 6 males (60%) and 4 females (40%). All 10 patients underwent circumferential resection of stenosed tracheal segment, cricoid split, interposition of costal cartilage graft and an anastomosis between augmented cricoid and trachea. Eight patients (80%) anterior cricoid split and 2 (20%) had anterior as well as posterior split. Average resected length of trachea was 2.39 cms. Cricoid split with costal cartilage augmentation is a feasible option to expand cricoid lumen in crico-tracheal stenosis. None except one of our patients required any further intervention in mean follow up of 42 months and all are free from primary symptoms. The functional results of the surgery were also excellent in 90% of the patients.

Keywords: Cricoid augmentation, Costal cartilage graft, Subglottic stenosis, Adults

Introduction

Crico-tracheal stenosis involves cricoid cartilage as well as adjacent tracheal segments. It is an uncommon but challenging complication of endotracheal intubation [1]. Crico-tracheal resection is the preferred approach adopted by most airway surgeons, though alternative treatment modalities have been reported in literature include laser vaporization of involved segment and serial dilatations with or without stenting, but these have not proved to be effective and are generally reserved to tide over acute crisis [2, 3]. There are reports of cricoid split with augmentation by costal cartilage graft, performed endoscopically as well as by open surgery in paediatric age group [4–8]. However, surgical series of the same in adults are sparse [9–11]. We present herein our results of cricoid augmentation with costal cartilage in complex crico-tracheal stenosis in adults.

Material and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained data of patients who underwent surgery for crico-tracheal stenosis at a tertiary care centre from March 2012 to September 2019. Their demographic and clinical data, pre-operative work up, intra-operative details and post-operative course was recorded. A pre-operative assessment of laryngo-pharyngeal neurological function by voice assessment and swallowing test was always done. All patients underwent contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of neck and thorax with 3D reconstruction of airways to assess the site of stenosis, length of involved segment, any distortion of distal airway, tracheomalacia, calcification in the wall of trachea, total length of airway and status of lung parenchyma (Fig. 1). Flexible bronchoscopy with appropriate size scope was done in awake condition to check the status of vocal cords, condition of the surrounding mucosa as well as the exact location and length of stenotic segment, diameter of stenosis along with distal tracheal length (Fig. 2). Stenosis was defined as Crico-tracheal if the proximal end of the stenosis was cranial to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomoprahic image showing cricoid narrowing

Fig. 2.

Pre operative bronchoscopy showing grade 4 cricoid stenosis

Need for possible cricoid augmentation was suspected preoperatively at bronchoscopy and was confirmed intra-operatively after assessing the cricoid lumen. Finding of subglottic stenosis with cricoid narrowing was taken as an indication for cricoid split and costal cartilage graft augmentation.

Surgical Details

The procedures were performed under general anaesthesia with airway secured with micro-laryngoscopy (MLS) tubes of appropriate size passed through the stenosis under fibreoptic bronchoscopic guidance. Preoperative dilatation was always done if the stenotic segment was < 5 mm in diameter. If a tracheostomy was in situ at the time of surgery, it was used by the anaesthetist to ventilate the patient in which case a fresh tracheostomy tube was inserted in a sterile way just before the start of surgery.

Patients were placed in supine position with support at shoulder level and neck extended. A horizontal incision was made two fingers above sternal notch, incorporating the tracheal stoma also in tracheostomized patients. After division of strap muscles and isthmus of thyroid, airway was exposed from hyoid bone up to trachea at the level of manubrium. The stenosed tracheal segment was mobilized circumferentially starting from the its lower end and going upward up to the inferior border of the cricoid ring. Complete suprahyoid and infrahyoid laryngeal drop was performed. During tracheal mobilization, dissection was kept close to the anterior tracheal surface using bipolar electrocautery, to avoid any inadvertent electrothermal injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Thereafter, a vertical incision was given over the stenosed segment of trachea and the endotracheal tube (micro-laryngeal surgery tube) was identified. The anaesthetist was asked to withdraw the endotracheal tube, ensuring the tip up to the level of vocal cords. This will expose the whole extent of the sub-glottic stenosis. The stenosed segment of trachea was then resected and airway was secured by cross field ventilation by a sterile flexo-metallic tube inserted into the distal cut end of trachea. The cricoid was now examined carefully for its luminal adequacy and decision to proceed with cricoid split was taken by operating surgeon. The decision of cricoid split was based on preoperative computed tomography and bronchoscopy findings, reinforced by the intraoperative findings. Based on diameter of cricoid, the extent and the symmetry of cricoid narrowing the decision of anterior, posterior or both splits were taken. If the stenotic involvement is involving only the anterior half, then anterior split was performed. However, if there is circumferential involvement, decision was taken to do both anterior and posterior cricoid split. If the stenotic involvement is involving only the anterior half, then anterior split was performed. However, if there is circumferential involvement, decision was taken to do both anterior and posterior cricoid split. The costal cartilage graft 3–4 cm in length was harvested in a sub-perichondrial fashion from 2nd costal cartilage. Using a scalpel, the cartilage graft was contoured into a small Tetragonal shape of adequate width to achieve normal cricoid lumen after interposition. Grooves were created on its lateral edges by a micro-drill for the cut ends of cricoid to fit into them (Fig. 3). The contoured costal cartilage piece was positioned between the separated cricoid edges and sutured to cricoid lamina with interrupted PDS sutures (Figs. 4, 5, 6). Cranially, the costal cartilage graft was sutured to the cricothyroid membrane.

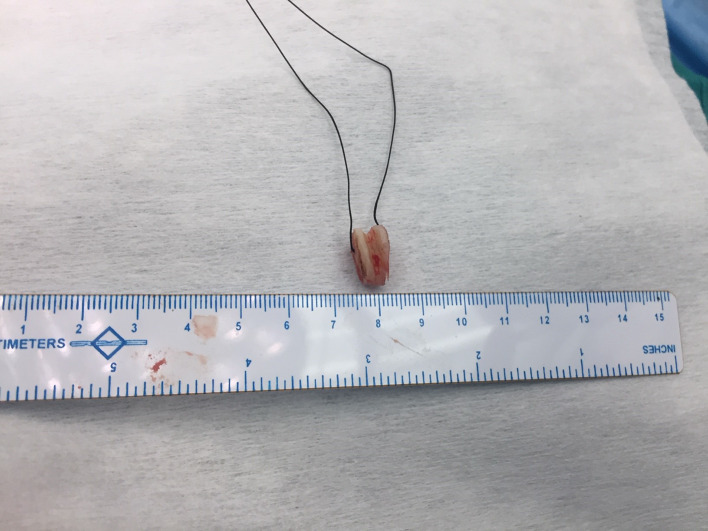

Fig. 3.

The Costal cartilage graft shaped to tetragonal shape

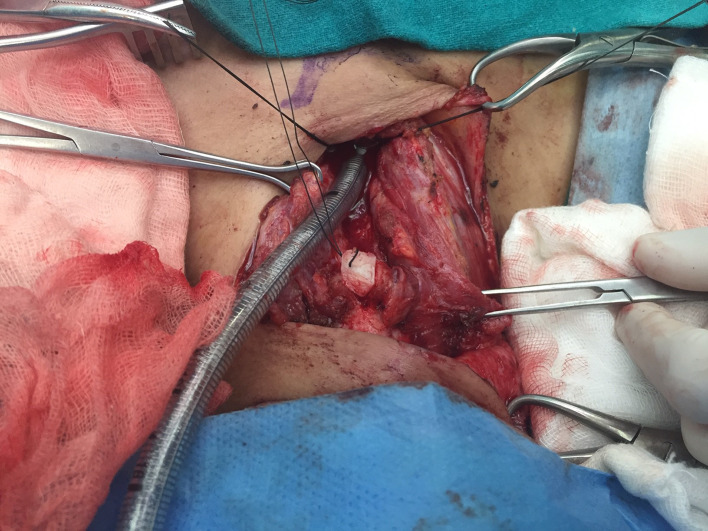

Fig. 4.

Cricoid splitting and positioning of costal cartilage

Fig. 5.

Placement of costal cartilage in cricoid split

Fig. 6.

Fixation of costal cartilage with cricoid by interrupted sutures

An anastomosis between the now augmented cricoid cartilage, and the distal cut end of the trachea was performed with interrupted 3“0” PDS sutures. Before completing the anterior layer of anastomosis, the flexo-metallic tube used for cross-field ventilation through distal tracheal segment was removed and the endotracheal tube, which had been withdrawn up to vocal cords, was pushed carefully, under vision across the anastomosis into the distal trachea and the ventilation was switched back to this tube. The anastomosis was now completed. At the end of procedure, an air leak test was always done to check the integrity of the anastomosis. After adequate homeostasis, a negative suction drain was placed close to the anastomosis, the strap muscles and thyroid were re sutured over the anastomosis and wound was closed in layers. 2 guardian stitches were placed between chin and chest wall to keep neck in partially flexed position. All the patients were extubated on the table, under bronchoscopic control to assess the vocal cords.

Patients were shifted to the recovery room for overnight monitoring and transferred to the ward the next morning. Adequate pain relief was provided to all, which ensured patient cooperation for aggressive chest physiotherapy to maintain complete lung expansion in post-operative period. Drainage tube was removed when the drainage was non-purulent/non-haemorrhagic and less than 20 ml in 24 h and there was no clinical evidence of leak. Ryle tube feed was started from day one, due to anticipated swallowing discomfort and dysphagia secondary to hyoid release and flexed neck position and to avoid the risk of aspiration after suprahyoid and infrahyoid release. The swallowing issue usually settles in 2–3 weeks at which time patients are gradually shifted to oral feeds. No patient needed ryle’s tube beyond 4 weeks. Hospital stay, postoperative anastomotic dehiscence, wound infection and other complications during hospital stay were analysed. All patients were followed up in outpatient department at weekly interval for 4 weeks and then every 6th month for the first two years and then yearly for up to 5 years. A chest X-ray was done at 1 month and at all subsequent visits. All patients underwent check bronchoscopy at 6 months (Fig. 7) and then yearly for 2 years to evaluate the anastomotic site. At six months follow up, a functional assessment was done and the results of surgery were considered ‘Excellent’ if voice, respiration and bronchoscopic examination were completely normal, ‘Satisfactory’ in case of mild hoarseness or shortness of breath on exercise not sufficient to impair normal activities, and ‘Poor’ if patient developed some major complication such as anastomotic dehiscence, restenosis or vocal cord paralysis.

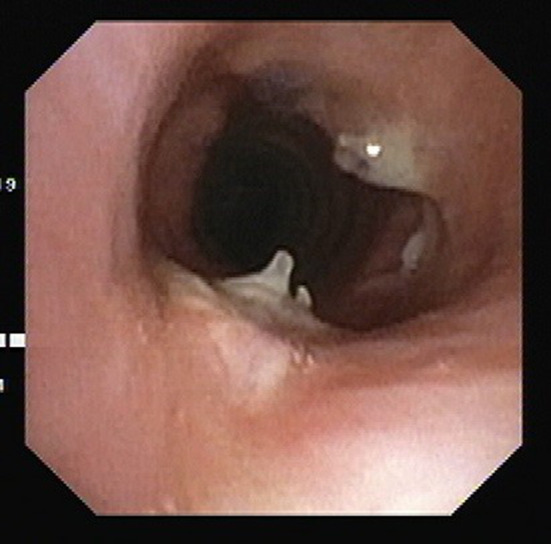

Fig. 7.

Bronchoscopy at 6 months follow up

Statistical Methods

Statistical testing was conducted with the statistical package for the social science system version SPSS 17.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. a significant difference.

Results

Ten patients underwent cricoid split with costal cartilage graft augmentation and crico-tracheal anastomosis between March 2012 and November 2019. The mean age was 29 years (range, 22–58 years). There were 6 males (60%) and 4 females (40%). Five patients (50%) had tracheostomy at the time of surgery and rest 5 had undergone interventions preoperatively in the form of repeated dilatations (4 patients) and stenting (1 patient). The average frequency of dilatation was 3 before patients were referred to us. Post intubation tracheal stenosis was the most common aetiology of crico-tracheal stenosis, in 7 patients (70%) and blunt trauma, tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthritis in 1 patient each. As per Cotton-Myer Grading of stenosis, 8 patients had grade 3 and 2 had grade 4 stenosis. All 10 patients underwent circumferential resection of stenosed tracheal segment, cricoid split, interposition of costal cartilage graft and an anastomosis between augmented cricoid and trachea. Eight patients (80%) anterior cricoid split and 2 (20%) had anterior as well as posterior split. Average resected length of trachea was 2.39 cms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demography and peri-operative variables

| Variable | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Male | 6 |

| Female | 4 |

| Mean age | 29 |

| Tracheostomy | 5 |

| Previous intervention | 5 |

| Dilatation | 4 |

| Stent | 1 |

| Etiology | |

| Post intubation | 7 |

| Blunt trauma | 1 |

| Tuberculosis | 1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 |

| Cotton-Myer grading | |

| Grade 3 | 8 |

| Grade 4 | 2 |

| Anterior split | 8 |

| Posterior split | 2 |

| Mean hospital stay time | 5 days |

| Average resected length | 2.39 cm |

| Wound related complication | 1 |

| Restenosis | 1 |

Post-operative recovery was uneventful in 9 (90%) patients. One patient developed subcutaneous emphysema on 3rd post-operative day, for which her neck wound was laid open and managed conservatively. Wound healed with secondary intention. Six weeks after surgery, this patient developed stridor. Bronchoscopy revealed restenosis at the anastomosis site for which bronchoscopic dilatations were done at weekly intervals for next 4 weeks. She settled thereafter, and has remained symptom free on follow-up. No complication was observed in any other patient. Average hospital stay was 5 days. All patients could re-start oral feeds between 2nd and 4th week and none required Ryle’s tube support beyond 4th week. At follow-up, no patient complained of any symptoms and check bronchoscopies at regular intervals, as described above, revealed healthy anastomosis. With a median follow up of 42 months (range 6–82 months) all patients were alive. The recovery was excellent in all except one patient who had anastomotic narrowing. However, she continues to do well after post-operative bronchoscopic dilatations.

Discussion

Anatomically, cricoid is the narrowest part of the airway up to carina and crico-tracheal stenosis is a complex disease of this part. Prolonged intubation is the commonest cause, with mechanical injury due to endotracheal tube leading to mucosal ischemia, ulceration and damage to the wall of airways [1, 2]. Prolonged or repeated trauma leads to fibrous scar formation which in due course leads to various degrees of stenosis. Most commonly it occurs in circumferential manner, however isolated anterior or posterior wall involvement is also seen. There are many other causes for crico-tracheal stenosis like idiopathic, post-irradiation, inhalation burns, tuberculosis, bacterial tracheitis, histoplasmosis and connective tissue disorder like scleroderma, relapsing polychondritis, poly-arteritis and Wegner’s granulomatosis [12]. In our series also, most common reported cause was post intubation in 70% cases.

Treatment of crico-tracheal stenosis remain complex and challenging. There are many modalities reported in literature but optimal management has not been established. Treatment modalities include endoscopic as well as surgical management. Endoscopic management includes balloon dilation, carbon dioxide (CO2) laser with radial incisions and endoscopic stent placement. Various surgical method includes circumferential resection of crico-tracheal junction with thyro-tracheal anastomosis, vertical split of anterior or posterior cricoid ring or both with interposition of cartilage or bone to maintain the enlarged lumen.

Feinstein et al. analysed 101 patients with crico-tracheal stenosis due to various causes which included 47 patients (46.5%) with idiopathic, 31 patients (30.7%) with post intubation, 9 patients (8.9%) with polyangiitis with granulomatosis, and 6 patients (5.9%) with other autoimmune diseases. Total 219 endoscopic interventions were done including both balloon dilation and lasers used in 117 (53.4%), balloon dilation alone done in 96 (43.8%) and laser alone done in 6 (2.7%). Mitomycin application as well as steroid injection were also used. They showed that endoscopic interventions were not able to alter patients from ending up for surgical management but could only prove a bridge in between [13]. In our series also, non-tracheostomized patients had an average of 3 interventions prior to surgery. These endoscopic measures help to tide over crisis situations and can be used as a bridge to surgical management.

Maddaus et al. reported 53 patients who underwent surgery for crico-tracheal stenosis with thyro-tracheal anastomosis. 29 patient required distal tracheostomy for varying period from 2 to 24 months because of glottis oedema. One patient had restenosis and 3 had recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in which 2 had permanent injury [14]. Collagen vascular diseases like Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing poly-chondritis, polyarteritis, scleroderma, and sarcoidosis should not be considered for circumferential resection and thryo- tracheal anastomosis because of very high chances of restenosis [15].

In paediatric age group, preferred method for crico-tracheal stenosis is anterior and/or posterior cricoid split and cartilage augmentation. Gustafson et al. reported success rate around 96% in a group of 200 children. Cartilage graft is successful in paediatric age group because these are softer, easy to tailor and not ossified at that age. However, when the stenosis is close to (< 5 mm) or involves the vocal cords (high subglottic or glottic stenosis), Crico-tracheal resection alone is not applicable because if the glottic component is left unsolved, the problem will persist and the appropriate approach for these cases is still controversial [16].

Very few studies have been reported in adults with this technique. Ricardo et al. described the anterior and posterior cricoid split and cartilaginous reconstruction with crico-tracheal anastomosis in 20 patients with distal protective tracheostomy and laryngeal stent placed in all patient. Eighty percent of patients were successfully decannulated in 23.4 months (range 4–55 months). In 4 (20%) patients the treatment failed and required multiple interventions and one had permanent stent insertion [9]. Similarly, Pradhan et al. reported 4 patient with cricoid split alone without crico-tracheal resection with silicone stent placement for 4 months each. All four patients were decannulated and airways was restored successfully without any complication [11]. Swain et al. reported 6 patients of crico-tracheal stenosis who underwent cricoid split and conchal cartilage augmentation along with silastic stent. Five patients were successfully decannulated after 3 months. One patient required resection anastomosis after failure [10] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison with other series

In our series we did cricoid split followed by costal cartilage graft interposition and crico-tracheal anastomosis in all the patients. All patients were extubated on the table. None required protective tracheostomy or stent placement in post-operative period. Except one patient who had wound related complication in immediate post-operative period and restenosis in late post-operative period, rest of the patients had uneventful recovery. We found cricoid split with costal cartilage augmentation to be a feasible option to expand cricoid lumen in crico-tracheal stenosis. None except one of our patients required any further intervention in mean follow up of 42 months and all are free from primary symptoms. The functional results of the surgery were also excellent in 90% of the patients.

Though we were able to manage this complex disease without any major complication but the major limitation of our study is small numbers and its retrospective nature. Further studies with larger number of patients are required to prove the experience reported by us with this technique in adults.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Study was approved by Institutional Ethical Board.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wain JC. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2003;13:231–246. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3359(03)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Andrilli A, Venuta F, Rendina EA. Subglottic tracheal stenosis. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(Suppl 2):S140–S147. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.02.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakache G, Primov-Fever A, Alon EE, Wolf M. Predicting outcome in tracheal and cricotracheal segmental resection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(6):1471–1475. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3575-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahl JP, Purcell PL, Parikh SR, Inglis AF., Jr Endoscopic posterior cricoid split with costal cartilage graft: a fifteen-year experience. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(1):252–257. doi: 10.1002/lary.26200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber ME, Modi VK, Ward RF, Gower VM, Thomsen J. Endoscopic posterior cricoid split and costal cartilage graft placement in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(3):494–502. doi: 10.1177/0194599812472435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuta S, Nagae H, Ohyama K, Tanaka K, Kitagawa H. Therapeutic effectiveness of costal cartilage grafting into both anterior and posterior walls for laryngotracheal reconstruction in acquired subglottic stenosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2021;37(5):555–559. doi: 10.1007/s00383-020-04812-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maddalozzo J, Holinger LD. Laryngotracheal reconstruction for subglottic stenosis in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987;96(6):665–669. doi: 10.1177/000348948709600610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutter MJ, Cotton RT. The use of posterior cricoid grafting in managing isolated posterior glottic stenosis in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(6):737–739. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terra RM, Minamoto H, Carneiro F, Pego-Fernandes PM, Jatene FB. Laryngeal split and rib cartilage interpositional grafting: treatment option for glottic/subglottic stenosis in adults. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(4):818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swain SK, Singh N, Samal R, Pani SK, Sahu MC. Use of conchal cartilages for laryngotracheal stenosis: experiences at a tertiary care hospital of Eastern India. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;68(4):445–450. doi: 10.1007/s12070-015-0955-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradhan T, Kapil S, Thakar A. Posterior cricoid split with costal cartilage augmentation for high subglottic stenosis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;60:147–151. doi: 10.1007/s12070-007-0120-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grillo HC, Mark EJ, Mathisen DJ, Wain JC. Idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis and its management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinstein AJ, Goel A, Raghavan G, et al. Endoscopic management of subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(5):500–505. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maddaus MA, Toth JL, Gullane PJ, Pearson FG. Subglottic tracheal resection and synchronous laryngeal reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104(5):1443–1450. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)34641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grillo HC, Mark EJ, Mathisen DJ, Wain JC. Idiopathic Laryngo-tracheal stenosis and its management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:80–87. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustafson LM, Hartley BE, Liu JH, Link DT, Chadwell J, Koebbe C, Myer CM, 3rd, Cotton RT. Single-stage laryngotracheal reconstruction in children: a review of 200 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(4):430–434. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.109007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]