Abstract

Diel patterns in foraging activity are dictated by a combination of abiotic, biotic and endogenous limits. Understanding these limits is important for insects because ectotherm taxa will respond more pronouncedly to ongoing climatic change, potentially affecting crucial ecosystem services. We leverage an experimental macrocosm, the Montreal Insectarium Grand Vivarium, to test the importance of endogenous mechanisms in determining temporal patterns in foraging activity of butterflies. Specifically, we assessed the degree of temporal niche partitioning among 24 butterfly species originating from the Earth's tropics within controlled environmental conditions. We found strong niche overlap, with the frequency of foraging events peaking around solar noon for 96% of the species assessed. Our models suggest that this result was not due to the extent of cloud cover, which affects radiational heating and thus limits body temperature in butterflies. Together, these findings suggest that an endogenous mechanism evolved to regulate the timing of butterfly foraging activity within suitable environmental conditions. Understanding similar mechanisms will be crucial to forecast the effects of climate change on insects, and thus on the many ecosystem services they provide.

Keywords: nectaring, chronobiology, greenhouse, niche, diel rhythm, Lepidoptera

1. Introduction

The activity of many animals and plants follows recurrent temporal patterns throughout yearly, seasonal and daily cycles [1]. Foraging is one of the most important processes within the diel activity of many organisms, determining movement in seeking resources and thus mediating growth, survival and reproduction [2,3]. Understanding temporal patterns in foraging has therefore long been central in ecology [2]. This has been especially important in the study of anthophilous insects given the implications of their foraging for ecosystem functioning and services (e.g. pollination) [4–6].

Three types of limits determine daily temporal patterns in foraging of anthophilous insects—abiotic, biotic and endogenous limits. First, because anthophilous insects are typically poikilotherms, the abiotic environment (e.g. temperature) limits their activity [5,7–9]. Second, biotic interactions (e.g. availability of food, predation or competition) can also mediate activity patterns [5,10,11]. Last, endogenous timing mechanisms (e.g. migrations) can evolve to regulate insect activity through time [9,12]. Biotic and abiotic limits affect activity dynamically, whereas endogenous timing mechanisms typically condition diel activity in addition to the immediate environment. How these processes interplay in determining the chronobiology of diel foraging in anthophilous insects remains poorly understood despite significant implications for ecology and conservation [6,9].

What determines the diel chronobiology of foraging remains elusive even for butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea), one of the most studied insect taxa [9,12,13]. Abiotic conditions determine whether butterflies can forage—see, e.g. the importance of thermal balance and wind speed for butterfly activity [5,7,8,14,15]. Conversely, biotic limits are usually less important in determining butterfly diel activity. Many butterfly species at a site are usually active at similar times [16], suggesting minor roles of intra- and interspecific competition (but see, e.g. [17]). Similarly, availability of nectar sources does not explain patterns in foraging activity throughout the day [5], suggesting little adaptive significance of synchrony between nectar production and butterfly foraging. Last, some butterflies evolved endogenous timing mechanisms, e.g. asynchrony in patrolling to facilitate coexistence [18], but the role of such mechanisms in determining foraging patterns is largely unknown [9].

Understanding butterfly foraging should be simpler than for other anthophilous insects because of the presumably negligible role of biotic limitations, yet untangling abiotic and endogenous limits has been insofar difficult [5,9]. Adult butterflies typically follow a unimodal temporal activity pattern that peaks around midday [5,16], but this pattern is correlated with daily fluctuations in environmental conditions (e.g. light and temperature), confusing interpretations. There seems to be temporal trends in activity even after controlling for abiotic conditions [14], but evidence of endogenous timing mechanisms remains rare [9]. Meanwhile, abiotic conditions impose a strong selection on butterfly behaviour [7,8,19,20], suggesting that butterfly activity might be mostly mediated by physiological constraints. As we enter decades of unprecedented climatic changes, understanding the importance of abiotic versus endogenous timing limits will be important to predict how foraging will change in these taxa and thus to forecast potential effects on ecosystem services [6,9].

We leverage an experimental macrocosm—the Montreal Insectarium Grand Vivarium (MIGV)—to assess the foraging chronobiology of 24 butterfly species from the Earth's tropics (figure 1). The MIGV is maintained at abiotic conditions ideal to maximize the activity of such species, thereby allowing a study of variation in butterfly foraging in species adapted to different environments but exposed to the same experimental conditions. Given the limited role of biotic interactions in determining patterns in foraging activity for butterflies [5], the MIGV provides a unique opportunity to test the importance of abiotic limits versus endogenous timing mechanisms.

Figure 1.

The MIGV is a tropical experimental macrocosm that, during this study, hosted 24 species of tropical butterflies (top section). We assessed the degree of overlap in foraging activity across these species to test the importance of abiotic constraints in determining butterfly diel foraging patterns. A high temporal niche partitioning (bottom-left) would suggest that, when being exposed to the same abiotic conditions, species that evolved in different regions adjust the timing of their diel foraging activity to match different abiotic optima. Conversely, a high temporal niche overlap (bottom-right) would suggest that endogenous timing mechanisms overcome abiotic optima, resulting in a synchronous pattern of foraging behaviour across species.

We focus on temporal patterns in diel butterfly foraging, assessing the degree of temporal niche partitioning versus overlap within our novel tropical assemblage (figure 1). We predict that butterfly nectaring in the MIGV can fall between two potential extreme patterns in response. First, because butterflies evolved to adapt to different environmental conditions, exposing species originating from different regions to the same abiotic conditions could result in differential foraging times (temporal niche partitioning) [21]. This could be due, e.g. to the evolution of different temperature optima [19,20], with species adapted to cooler climates able to forage when the abiotic environment is not suitable for organisms requiring warmer temperatures. Alternatively, because all butterflies originated from a common ancestor [13], they might share a preference for certain conditions and thus show no differential response in foraging through time (temporal niche overlap) [22,23]. This could be explained by advantages in maintaining synchronous foraging activity, e.g. because synchrony might reduce predatory pressure.

2. Methods

The MIGV hosts a tropical macrocosm (630 m2; figure 1) maintained at a temperature of approximately 22°C overnight (19.00–07.00) and 27°C during the day (07.00–19.00), at controlled moisture and air flow. It also provides butterflies with many flowering plants, such that competition for nectar is minimal. These conditions are suitable for the activity of tropical butterflies [24], allowing us to test for endogenous timing mechanisms regulating nectaring activity. We sampled four similar sites spread across the MIGV between 6 April and 19 April 2022, 80 times between 07.00 and 17.00. We performed 20 sampling cycles, each cycle consisting of a 2 min, 10 m2 point count per site to record foraging events. Extensive details on sampling and methods are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

We modelled (1) the number of butterflies observed foraging within each point count, and (2) the probability of observing a foraging event for a butterfly species relative to all the other species observed during the study. For (1), we assumed a Poisson distribution of the response. We compared three candidate models—a null model where counts are assumed to vary randomly throughout the day (Null), a model assuming a linear effect of time (hour of the day) (Time) and a model assuming a quadratic effect of time (Time_sq). All models included a site fixed effect. We present the best model based on the Watanabe–Akaike information criterion (WAIC), an information theoretic approach to model selection [25]. By performing model selection following an information-theoretical paradigm, model fit and complexity are both used to inform our inferences, prioritizing parsimonious models. For (2), we assumed a probit distribution of the responses. We fit a hierarchical multi-species model where the probability of observing a species relative to the other foraging events is modelled as a function of time. The effect of time is estimated for all species—including those with a small sample size—through Bayesian shrinking. Our null expectation, consistent with niche conservatism [22], is that all the species follow the same trend, in which case the effect of time on their probability of being observed foraging relative to the other foraging events will be zero (figure 1, bottom-right). Deviation from zero would suggest that species evolved to be active at different times through the day, consistent with niche partitioning [21] (figure 1, bottom-left). In the electronic supplementary material, we provide post hoc sensitivity analyses for both (1) and (2), to assess how temporal patterns relate to variation in sampling through time, in temperature and in cloud cover. The analysis was conducted in software R [26] using packages brms and Hmsc [25,27].

3. Results

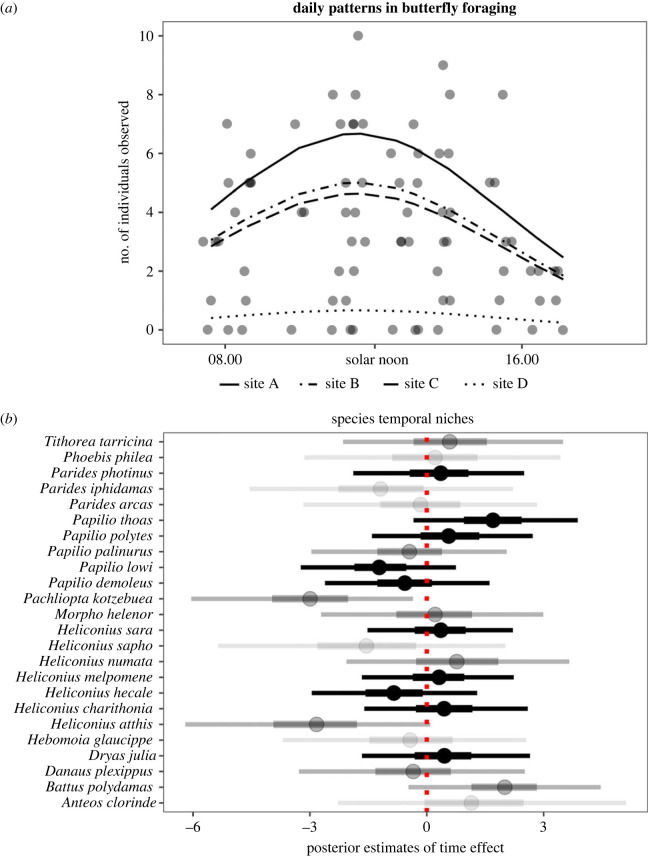

We observed 275 foraging butterflies belonging to 24 species (mean number of individuals per species = 13.4, s.d. = 10.5; n = 80 point counts; figure 2). Sixty-three per cent of foraging episodes (173/275 observations) occurred between 10.00 and 14.00, and the most supported model predicting the number of foraging butterflies throughout the day includes a quadratic effect of time (WAICtime_sq = 299 versus WAICtime = 312 or WAICnull = 311.1). The model predicts peak foraging activity around solar noon (figure 2a). This unimodal activity pattern is remarkably consistent across taxa (figure 2b). For 23 of 24 species (96%), posterior estimates of the effect of time on the relative probability of observing the species include zero in the 2.5%–97.5% posterior interval (figure 2b, narrower lines). When considering the 25%–75% posterior interval, this pattern remains for 16 of 24 species (67%) (figure 2b, thicker lines). These patterns are robust to the inclusion of environmental covariates known to affect butterfly activity (S2–4).

Figure 2.

Temporal patterns in butterfly foraging. (a) Number of butterflies observed foraging throughout the day, with line type showing trends at four sampling locations within the MIGV. The data support a unimodal foraging activity pattern across the assemblage, with peak around solar noon. (b) Posterior estimates of the effect of time on the probability of observing each of 24 species present in the MIGV relative to the other species. Posterior estimates different from zero suggest divergence from the unimodal pattern observed in (a), with negative estimates suggesting increased foraging activity before solar noon, and positive estimates suggesting increased foraging activity after solar noon. Dots represent the median posterior estimates for the effect of time (thick lines: 25%–75% quantiles; narrow lines: 2.5%–97.5% quantiles). Twenty-three of 24 species did not differ substantially from the pattern observed in (a), with the posterior 2.5%–97.5% quantiles including zero, a result that suggests strong temporal niche overlap. Colours represent sample size (black: greater than 15 observations, 10 species; dark grey: between five and 15 observations, eight species; light grey: less than five observations, six species).

4. Discussion

We found strong support for the temporal niche overlap hypothesis (figure 1, bottom-right; figure 2b). In other words, butterflies forage synchronously within the MIGV, a result somewhat surprising given the diverse provenance of the species we assessed (electronic supplementary material, table S2). While we predicted that diel patterns in foraging could vary across species given their different climatic optima, the conditions provided by the MIGV appeared sufficient for all butterfly species to forage at their preferred time, which seems to approach solar noon for virtually every taxon assessed (figure 2b). The only exception to the pattern, P. kotzebuea, might be adapted to forage earlier, but we did not notice any specific trait that would explain such differences (e.g. provenance from cooler climates or wing colour patterns; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Perhaps, the most parsimonious explanation is that one out of 24 species could differ by chance. Ultimately, each species contributed equally and proportionally to their abundance to the emergent, unimodal pattern in foraging activity observed at the assemblage level (figure 2a). This is consistent with niche conservatism, the propensity of ecological traits to remain similar over time [22,23], and with the hypothesis that a common ancestor might have evolved an endogenous mechanism to forage at solar noon. The endogenous mechanism hypothesis is also consistent with observed decreases in activity after solar noon, a behaviour occurring despite temperatures being still suitable in the MIGV (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

The mechanisms underlying this synchronous pattern remain unclear. We speculate that patterns in sunlight might be used by butterflies as an environmental cue mediating diel foraging activity. For instance, UV-reflecting patterns on flowers and plants might trigger behavioural responses in the hours of the day with most light, although the observed temporal trends were robust to considerations of cloudy weather, suggesting that light intensity is not the main driver of this synchronous foraging behaviour. One phenomenon that is not affected by weather conditions is sunlight orientation (which is not controlled in the MIGV), such that butterflies could still regulate the timing of their foraging activity based on patterns in sunlight even in cloudy weather. Many insects have evolved photoreceptors and use them to regulate their activity through time [1], including sensors that detect sunlight polarization [28]. Meanwhile, the perception of polarized light has been observed in many butterfly species [29] and linked to behaviours including mating [30] and orientation [31]. Even when an individual of a given species is removed from its original distribution, sunlight polarization remains an identifiable environmental cue that would signal when the sun is highest in the sky [28], signalling temporal optima in foraging.

Many insect species evolved endogenous timing mechanisms triggered by environmental cues (e.g. degree days, sunlight polarization or photoperiods) to maintain temporal behavioural patterns [32]. Similar mechanisms can also influence foraging in anthophilous insects, e.g. moths and plants have co-evolved synchronous patterns that facilitate insect foraging and plant pollination [12], and diel activity patterns in foraging for Diptera and Hymenoptera during arctic summers that expose pollinators to prolonged periods of suitable abiotic conditions also follow unimodal trends [9]. It remains unclear what advantage, if any, comes for butterflies in foraging at the same hour of the day. Perhaps this time window provides an optimal compromise between insectivorous birds' activity and abiotic conditions [33]. Another hypothesized mechanism, the coevolution of butterfly activity patterns with nectar production and viscosity patterns during a day, has found so far little support [5].

We stress that endogenous timing mechanisms are conditional on abiotic conditions necessary for butterflies to function (e.g. minimum body temperature) [7]. For instance, in field conditions, noon can be too hot for butterflies to forage, and some days might be too cold for their activity [14,24]. Abiotic minima are particularly important in determining daily foraging patterns in limiting environments, such as alpine and arctic systems, where a variety of adaptations evolved to facilitate butterfly activity [7,8,34]. These environments are the most exposed to ongoing climate change [34]. It will be important to understand whether a conflict between endogenous timing mechanisms and exogenous abiotic conditions will affect the timing and effectiveness of butterfly foraging. Foraging is one of the most important activities for an animal, and in the case of anthophilous insects is also crucial for pollination, and thus for a variety of ecosystem services [6,9]. Species are expected to respond to changes in climate through several processes including evolution, behavioural and morphological plasticity, and phenological shifts [34], but the role of endogenous timing mechanisms in mediating these processes is largely unknown.

Ultimately, our study hints at the potential of greenhouses and vivaria like the MIGV as scientific hubs. With very few exceptions (e.g. [11]), these units have been underappreciated as resources for research. Many processes are inherently difficult to study in nature, and there has been an increasing appreciation for experimental systems spanning a variety of scales [35,36]. Vivaria can provide experimental conditions across much larger spatial scales than typical experiments [36], opening opportunities to answer questions on the ecology and biology of many organisms. Of course, like every experimental system, there are important caveats to keep in mind and not every parameter can be controlled (electronic supplementary material). Here, we assessed the chronobiology of a novel assemblage of tropical butterflies, finding evidence that an endogenous timing mechanism likely regulates butterfly foraging activity. As climates are moving towards unprecedented conditions, it will be important to understand whether endogenous timing mechanisms might become maladaptive, whereby butterflies will tend to forage in suboptimal conditions, negatively affecting their fitness. Our study identifies this aspect as an important avenue for research on the potential impacts of climate change on the behaviour of anthophilous insects, and thus on the provision of many ecosystem services, particularly pollination.

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank the laboratory and horticulture crews, without whom this work would not have been possible, and MIGV staff for their kind support throughout the study.

Data accessibility

Data and scripts are provided in the electronic supplementary material [37] and are also available on the Dryad Digital Repository: https://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.rfj6q57fs [38].

Authors' contributions

F.R.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; A.-P.D.P.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology and writing—original draft; M.L.: conceptualization, methodology and writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We acknowledge the support of a Mitacs Accelerate Fellowship (grant no. IT23330).

References

- 1.Pittendrigh CS. 1993. Temporal organization: reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 55, 16-54. ( 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.000313) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens DW, Krebs JR. 1986. Foraging theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson DH. 1980. The comparison of usage and availability measurements for evaluating resource preference. Ecology 61, 65-71. ( 10.2307/1937156) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winfree R, Reilly JR, Bartomeus I, Cariveau DP, Williams NM, Gibbs J. 2018. Species turnover promotes the importance of bee diversity for crop pollination at regional scales. Science 359, 791-793. ( 10.1126/science.aao2117) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrera CM. 1990. Daily patterns of pollinator activity, differential pollinating effectiveness, and floral resource availability, in a summer-flowering Mediterranean shrub. Oikos 58, 277. ( 10.2307/3545218) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cusser S, Haddad NM, Jha S. 2021. Unexpected functional complementarity from non-bee pollinators enhances cotton yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 314, 107415. ( 10.1016/j.agee.2021.107415) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kevan PG, Shorthouse JD. 1970. Behavioural thermoregulation by high arctic butterflies. Arctic 23, 268-279. ( 10.14430/arctic3182) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland J. 1982. Melanism and diel activity of alpine Colias (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Oecologia 53, 214-221. ( 10.1007/BF00545666) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoller L, Bennett JM, Knight TM. 2020. Diel-scale temporal dynamics in the abundance and composition of pollinators in the Arctic summer. Sci. Rep. 10, 21187. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-78165-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomson DM, Page ML. 2020. The importance of competition between insect pollinators in the Anthropocene. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 38, 55-62. ( 10.1016/j.cois.2019.11.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukano Y, Tanaka Y, Farkhary SI, Kurachi T. 2016. Flower-visiting butterflies avoid predatory stimuli and larger resident butterflies: testing in a butterfly pavilion. PLoS ONE 11, e0166365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady D, Saviane A, Cappellozza S, Sandrelli F. 2021. The circadian clock in Lepidoptera. Front. Physiol. 12, 776826. ( 10.3389/fphys.2021.776826) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawahara AY, Plotkin D, Hamilton CA, Gough H, St Laurent R, Owens HL, Homziak NT, Barber JR. 2018. Diel behavior in moths and butterflies: a synthesis of data illuminates the evolution of temporal activity. Org. Divers. Evol. 18, 13-27. ( 10.1007/s13127-017-0350-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riva F, Gentile G, Bonelli S, Acorn JH, Denes FV. 2020. Of detectability and camouflage: evaluating Pollard Walk rules using a common, cryptic butterfly. Ecosphere 11, e03101. ( 10.1002/ecs2.3101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribeiro DB, Prado PI, Brown KS Jr, Freitas AVL. 2010. Temporal diversity patterns and phenology in fruit-feeding butterflies in the Atlantic forest. Biotropica 42, 710-716. ( 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2010.00648.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollard E. 1977. A method for assessing changes in the abundance of butterflies. Biol. Conserv. 12, 115-134. ( 10.1016/0006-3207(77)90065-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunte K. 2008. Competition and species diversity: removal of dominant species increases diversity in Costa Rican butterfly communities. Oikos 117, 69-76. ( 10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16125.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Roy C, Roux C, Authier E, Parrinello H, Bastide H, Debat V, Llaurens V. 2021. Convergent morphology and divergent phenology promote the coexistence of Morpho butterfly species. Nat. Commun. 12, 7248. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-27549-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devictor V, et al. 2012. Differences in the climatic debts of birds and butterflies at a continental scale. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 121-124. ( 10.1038/nclimate1347) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parmesan C, et al. 1999. Poleward shifts in geographical ranges of butterfly species associated with regional warming. Nature 399, 579-583. ( 10.1038/21181) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finke DL, Snyder WE. 2008. Niche partitioning increases resource exploitation by diverse communities. Science 321, 1488-1490. ( 10.1126/science.1160854) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiens JJ, Graham CH. 2005. Niche conservatism: integrating evolution, ecology, and conservation biology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 36, 519-539. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102803.095431) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiens JJ, et al. 2010. Niche conservatism as an emerging principle in ecology and conservation biology. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1310-1324. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01515.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Swaay C, et al. 2015. Guidelines for standardised global butterfly monitoring. Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network, Leipzig, Germany. GEO BON Tech. Ser. 1, 32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bürkner PC. 2017. Brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1-28. ( 10.18637/jss.v080.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Core Team. 2021. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. See http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tikhonov G, Opedal ØH, Abrego N, Lehikoinen A, de Jonge MMJ, Oksanen J, Ovaskainen O. 2020. Joint species distribution modelling with the r-package Hmsc. Methods Ecol. Evol. 11, 442-447. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.13345) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krapp HG. 2007. Polarization vision: how insects find their way by watching the sky. Curr. Biol. 17, R557-R560. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelber A. 1999. Why ‘false’ colours are seen by butterflies. Nature 402, 251. ( 10.1038/46204) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweeney A, Jiggins C, Johnsen S. 2003. Insect communication: polarized light as a butterfly mating signal. Nature 423, 31-32. ( 10.1038/423031a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reppert SM, Zhu H, White RH. 2004. Polarized light helps monarch butterflies navigate. Curr. Biol. 14, 155-158. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosbash M. 2009. The implications of multiple circadian clock origins. PLoS Biol. 7, e62. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkbeiner SD, Briscoe AD, Reed RD. 2012. The benefit of being a social butterfly: communal roosting deters predation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 279, 2769-2776. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.0203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill GM, Kawahara AY, Daniels JC, Bateman CC, Scheffers BR. 2021. Climate change effects on animal ecology: butterflies and moths as a case study. Biol. Rev. Camb. Phil. Soc. 96, 2113-2126. ( 10.1111/brv.12746) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Szalay FA, Batzer DP, Resh VH. 1996. Mesocosm and macrocosm experiments to examine effects of mowing emergent vegetation on wetland invertebrates. Environ. Entomol. 25, 303-309. ( 10.1093/ee/25.2.303) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen CD, Hargreaves AL. 2020. Miniaturizing landscapes to understand species distributions. Ecography 43, 1625-1638. ( 10.1111/ecog.04959) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riva F, Drapeau Picard A-P, Larrivée M. 2023. Butterfly foraging is remarkably synchronous in an experimental tropical macrocosm. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6470010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Riva F, Drapeau Picard A-P, Larrivée M. 2023. Data from: Butterfly foraging is remarkably synchronous in an experimental tropical macrocosm. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.rfj6q57fs) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Riva F, Drapeau Picard A-P, Larrivée M. 2023. Butterfly foraging is remarkably synchronous in an experimental tropical macrocosm. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6470010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Riva F, Drapeau Picard A-P, Larrivée M. 2023. Data from: Butterfly foraging is remarkably synchronous in an experimental tropical macrocosm. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.rfj6q57fs) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Data and scripts are provided in the electronic supplementary material [37] and are also available on the Dryad Digital Repository: https://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.rfj6q57fs [38].