Abstract

Qualitative health research is ever growing in sophistication and complexity. While much has been written about many components (e.g. sampling and methods) of qualitative design, qualitative analysis remains an area still needing advanced reflection. Qualitative analysis often is the most daunting and intimidating component of the qualitative research endeavor for both teachers and learners alike. Working collaboratively with research trainees, our team has developed SAMMSA (Summary & Analysis coding, Micro themes, Meso themes, Syntheses, and Analysis), a 5-step analytic process committed to both clarity of process and rich ‘quality’ qualitative analysis. With roots in hermeneutics and ethnography, SAMMSA is attentive to data holism and guards against the data fragmentation common in some versions of thematic analysis. This article walks the reader through SAMMSA’s 5 steps using research data from a variety of studies to demonstrate our process. We have used SAMMSA with multiple qualitative methodologies. We invite readers to tailor SAMMSA to their own work and let us know about their processes and results.

Keywords: ethnography, hermeneutics, qualitative analysis, qualitative coding

Introduction

As qualitative research gains in popularity and utility, it also grows in its sophistication and in what it can achieve. What was called ‘generic’ qualitative research – that is, qualitative research devoid of formal methodology (Caelli et al., 2003) – is no longer commonly published in health journals. Taking this commitment further, a recent editorial in the Canadian Journal of Public Health announced a new standard for what their journal will accept. The editors write that ‘bare bones’ qualitative research – that is, research that ‘treats qualitative research as little more than a tool for collecting data that are presented within the writing convention of positivist, quantitative research’ (Mykhalovskiy et al., 2018, p. 614–615) – is no longer welcome in the journal (Mykhalovskiy et al., 2018). Specifically, this mainstream health journal requires all qualitative manuscripts to have at least a minimal commitment to what they call ‘critical, theoretically engaged’ qualitative research.

Pushing this trend forward, qualitative scholars have contributed to increasing the sophistication of many elements of qualitative design. Examples include sampling (Vasileiou et al., 2018), writing fieldnotes (Phillippi & Lauderdale, 2017), and writing results (Eldh et al., 2020). While all elements are essential, a particularly challenging and high stakes dimension of this renovation is analysis. Yet, to date, the sophistication of data analysis has not been well explicated in the literature. Qualitative methodologists, Eakin and Gladstone (2020), recently argued that there is a continuing tendency in qualitative studies of ‘cataloguing data into pre-existing concepts and scouting for “themes”’ (Eakin & Gladstone, 2020, p. 11); further, that basic thematic analysis misses the potential of qualitative research to advance knowledge. Likewise, the ‘bare bones’ version mentioned above critiques a missed analytic opportunity: Mykhalovskiy and colleagues take issue with the common practice of reducing sophisticated social theories to descriptive conceptual models and typologies. In so doing, researchers miss the potential of using social theory to inspire the production of analytic processes and interpretive results (Mykhalovskiy et al., 2018).

What should quality qualitative analysis produce? Eakin and Gladstone argue that rigorous qualitative analysis should intentionally contribute to both (a) the discovery of new knowledge and (b) the reconceptualization of prior ideas (Eakin & Gladstone, 2020). Experience tells us, however, that the analytic process can be the most intimidating aspect of qualitative training for junior scholars. Many introductory qualitative research courses leave students with the feeling that analysis is an enigma that cannot be unpacked in a classroom; it must be struggled through. Further, that the learning curve from basic coding and theme building to quality analysis is steep and long.

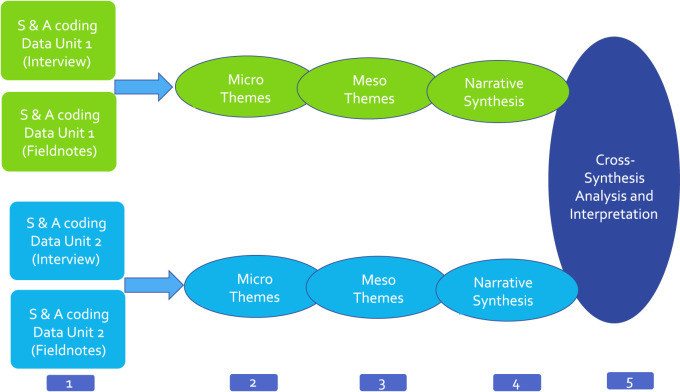

To address these problems, the following article reports on SAMMSA, an acronym for a 5-step analytic method that can be adapted for many qualitative methodologies. SAMMSA stands for Summary & Analysis coding, Micro themes, Meso themes, Syntheses, and Analysis (see Figure 1). SAMMSA represents our research team’s commitment to helping newcomers to qualitative inquiry feel less intimidated and more empowered to produce ‘quality’ qualitative analysis. Our team of authors includes two senior scholars (MEM and FAC) trained in multiple qualitative methodologies and two research trainees (SS and KL) focused on explicating the analytic steps in order to reduce feelings of intimidation. As an analytic method, SAMMSA is committed to fulfilling both of Eakin and Gladstone’s standards for qualitative analysis: the process carefully tacks back and forth between old and new knowledge, and deductive and inductive theorizing. That is, within this analytic process, we continually revisit prior (deductive) knowledge while enabling new (inductive) insights both from the data generated as well as through critical reflection on the theoretical ideas that helped shape the study design.

Figure 1.

SAMMSA’s 5-step process: An example with two data units.

The VOICE Team

Our research team, VOICE (Views on Interdisciplinary Childhood Ethics), is a Canadian-based inter-university team started in 2010 to advance theory and practice regarding children’s agency. Our work challenges common conceptions of children as morally immature and aims to innovate knowledge and develop strategies for addressing ethical concerns among young people (Carnevale et al., 2021). To do this work, we have developed our own methodological framework, called participatory hermeneutic ethnography (Montreuil & Carnevale, 2018), to orient our research specifically for health experiences research with children. This framework is rooted in the hermeneutic philosophy of Charles Taylor (Taylor, 2004).

While each of the components of our framework – participatory, hermeneutic, and ethnography – has a rich philosophical and methodological history, the practical question of how to analyze the qualitative data generated through our studies was uncharted territory. One of our authors (FAC) is trained in a hermeneutic tradition, and so is committed to a circular navigation of part–whole relations (Taylor, 1971). For example, a ‘part’ can refer to an individual participant, whereas the ‘whole’ refers to a social settings (e.g. family) in which participants live and navigate their experiences. Another teammate (MEM) comes from a critical ethnographic tradition and so embraces the ‘theory in, theory out’ richness of ethnographic inquiry, theorizing results in light of the social conceptualizations brought into the study, and purposefully working to critically engage these theoretical ideas with our generated data. Importantly, both hermeneutic and ethnographic traditions are committed to data holism and guarding against excessive data fragmentation in the analytic process.

As the saying goes, the best way to learn something is to teach it (Duran, 2017). Working closely with our trainees (SS and KL), we created SAMMSA, a 5-step analytical approach with careful attention to how we should code, synthesize, analyze, and interpret our data. While we developed the prototype for SAMMSA within participatory hermeneutic ethnography (Siedlikowski et al., 2022), we have honed its potential with trainees and colleagues outside of our VOICE team, using diverse methodologies and a range of health topics. For example, we have used early versions of SAMMSA in qualitative description studies (Mellett & Macdonald, 2022) and focused ethnography (Kim et al., 2021).

In our earlier publications, we described our process as a version of thematic analysis. However, we have found that SAMMSA holds up well as an analytic method for many rigorous qualitative (and mixed-methods) endeavors, and that it goes beyond what many studies report as thematic analysis. Additionally, trainees have reported that SAMMSA has made producing rigorous qualitative analysis feel less daunting. As experienced by the two trainee authors on this paper (SS and KL), SAMMSA’s five steps provide a clear process for generating robust analysis which brings confidence to their abilities to produce quality work. In the words of SS:

The SAMMSA step-wise approach provides a clear, common language with which to work while conducting data analysis as a team, thus fostering trustworthiness and confidence in the analysis process. It also facilitates project progress tracking, due to the ability to clearly indicate at what step a trainee is at in the analysis.

In the words of KL:

SAMMSA makes qualitative analysis easier to learn, practice, discuss, and teach. Learning to conduct qualitative analysis was daunting for me. Before SAMMSA, I felt like analysis was like learning to draw from a book, where Step 1 began with drawing a circle, and Step 2 already required shading a photorealistic owl! SAMMSA’s explicit, step-wise approach helped guide me through the process, which made ‘drawing the owl’ feel more manageable and helped me become confident in my work. This confidence was important to me because I wanted to handle data with the respect that I felt it deserved. SAMMSA also helped me identify where I was struggling, communicate my challenges, and receive the support I needed.

Thus, SAMMSA has the potential to enhance the quality of qualitative analysis within many qualitative designs (including within mixed-methods research), both for trainees and advanced scholars. And so, we felt it is important to formalize and share SAMMSA with the qualitative research community more broadly.

What Is SAMMSA?

SAMMSA is an acronym built from our step-by-step analytic method, moving from coding through to synthesis and interpretation. SAMMSA is theoretically grounded in hermeneutics and methodologically grounded in ethnography. Its main characteristics are as follows:

• it uses both deductive and inductive coding strategies;

• it relies on a thematic-type analysis including Micro followed by Meso themes;

• it uses a part–whole synthesis technique to ensure the integration of an entire data set remains attentive to the specificities of salient data points.

The five steps are as follows (Figure 1):

1. S&A: Summary and Analysis coding

2. M1: development of Micro themes

3. M2: development of Meso themes

4. S: generation of Narrative Syntheses

5. A: cross-syntheses Analysis & Interpretation

What counts as data in a project will guide a team in how to tailor SAMMSA for a particular study. SAMMSA was originally designed for interview-based data, focused on verbatim transcripts of individual interviews and focus groups, and their accompanying fieldnotes. The analysis focuses first on individual ‘data units’ (e.g. an individual interview or focus group with accompanying fieldnotes) and then on integrating all data units by asking how the data overlap, coalesce, and/or diverge. We have since adapted SAMMSA for participant-observation fieldnotes and document analysis as well.

SAMMSA was originally developed using word-processing software (e.g. Microsoft Word), relying on formatting features such as margin comments (e.g. for the S&A coding), and in-text formatting (e.g. bold, italics, and title/subtitle scaffolding) to itemize and position relationships among themes. The figures throughout this article demonstrate examples of how this formatting can be used. Note: all data extracts in this article come from studies with IRB approvals including participant informed consent and assent. Each extract has been adapted and anonymized for the purposes of this article.

The 5-Step SAMMSA Approach

Summary and Analysis (S&A) Coding

After data transcription, the first step in SAMMSA is coding the data. We begin with one ‘data unit’ (e.g. an interview and accompanying fieldnotes) in which we identify ‘data segments’ that seem relevant to the research question. A data segment corresponds to one idea being expressed. Each data segment is generally one or two sentences; it could be shorter. It would be rare to have a data segment that includes more than a short paragraph. Data segments are coded with S&A codes as follows.

The S Code

For each data segment, we write one Summary (S) code. The S code is a shortened version of what was said in the interview or written in the fieldnotes. As such, it is the first step in data abstraction. S codes are inductive; that is, they are based on the data as present in the text. To write the S code, we summarize a data segment. In doing so, we consider the person speaking in the transcript, or writing the fieldnote, as the main agent and frame the code around their voice. For instance:

Participant: I really feel that this policy is excluding kids like me.

Participant S code: The participant ‘really’ feels the policy is ‘excluding’ ‘kids like me’.

Fieldnote: I was frustrated by the resistance I felt from the administrative assistant – she was not forthcoming with information about the Day Program.

Fieldnote S code: The researcher was ‘frustrated’ by what they felt was ‘resistance’ from the administrative assistant regarding giving information about the Day Program.

Quotation marks are used in the S code when an in vivo word or phrase well captures the data segment. If we had written the Participant S code as The participant really feels the policy is excluding kids like her, then when the code is extracted from the data segment, it would not be clear to what extent the adverb really is our own interpretation or the participant’s (i.e. did the participant simply ‘feel’ this or did they ‘really feel’ this?).

In addition to capturing the participant’s or fieldnote writer’s words as authentically as possible, with S codes, we are careful not to provide evaluations or interpretations about the words. The goal in the Summary is to understand and learn about what the person is expressing and manifesting through the interaction, not to assess or interpret them. The following S codes would be considered poorly written for the above data segments:

Participant S code: The participant feels strongly that the policy excludes other children.

Participant S code: The participant feels it is unfair that the policy excludes her.

Fieldnote S code: The researcher feels the administrative assistant did not want to share information about the Day Program.

Fieldnote S code: The researcher was frustrated by the administrative assistant’s resistance.

The A Code

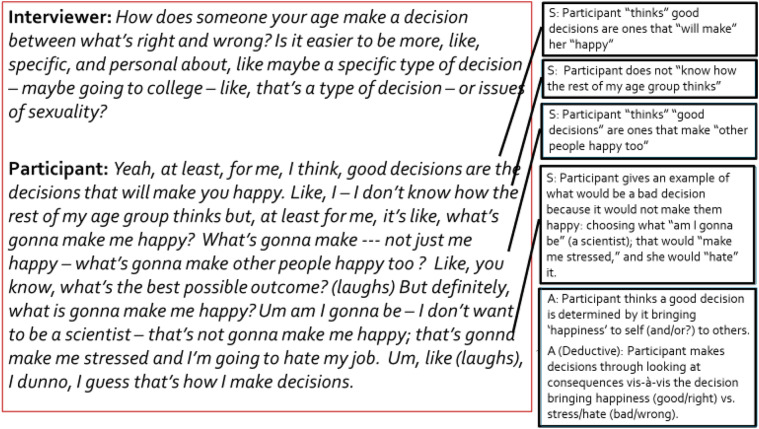

The A code is an interpretation or provisional inference built from the S code, not from the verbatim. Just as the S code is a summary of – and therefore an abstraction from – the text, the A code is an abstraction of the S code. Not all S codes will have an A code; further, some S codes will have more than one A code. A codes can include speculative links to prior A codes for the current data unit; for example, to other places in a participant’s transcript, or in the case of focus group transcripts, to other participants in the same transcript. As analysis progresses, A codes could reference other data units in the data set. Figure 2 demonstrates S&A codes and how we use word-processing software to report them within an interview transcript.

Figure 2.

Example of Summary and Analysis codes using word-processing software.

Another important feature of A codes is that they can have deductive elements. The example in Figure 2 is taken from a study that purposely used a Childhood Ethics framework built upon concepts of moral experience (Hunt & Carnevale, 2011). Embedded in the concept of moral experience are the spectra from good to bad and right to wrong. In the example, the interviewer specifically frames their question in the language of moral experience:

Interviewer: How does someone your age make a decision between what is right and wrong?

To signal that there is a deductive idea being imposed on the analysis, we add a note to A codes describing any deductive elements. The last A code in Figure 2 is a deductive code. Without an explicit note within the code, the reader should assume the A codes are inductive.

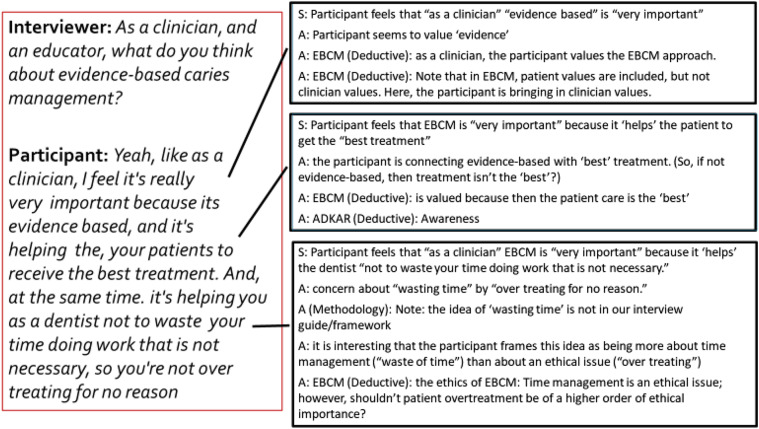

In another study, we interviewed clinical dental educators to understand their perspectives on the possibility of introducing a new curriculum within the undergraduate dental clinic. In this study, we explicitly used the ADKAR implementation framework (Hiatt, 2006) which is a change management model. ADKAR helped us conceptualize the challenges and opportunities the participants discussed in their interviews about introducing a new way of teaching students about assessing and managing dental caries, called Evidence-based Caries Management (EBCM) (Tikhonova et al., 2020). Thus, in this study, we had two conceptual frames: EBCM and ADKAR. Both were foundations for the interview guide. For example, we asked participants directly about EBCM, and we used the ADKAR concepts (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) to probe participant responses. In so doing, we created explicit opportunities for deductive A codes, as is demonstrated in Figure 3 (also note in Figure 3 a methodology A code reflecting on the study design).

Figure 3.

Example of deductive Analysis codes.

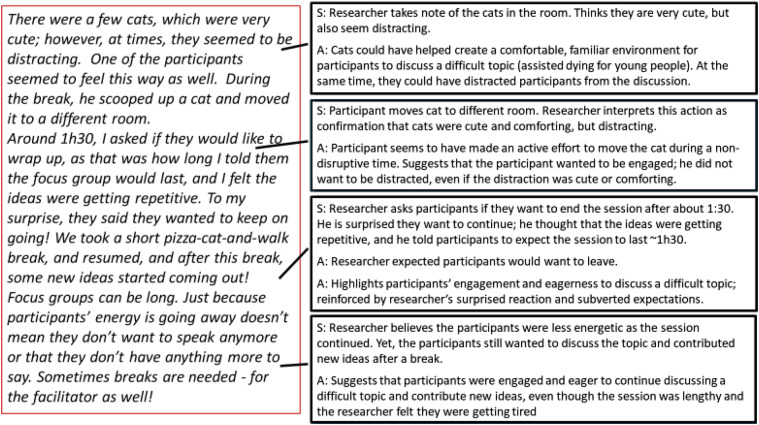

S&A coding can also be applied to fieldnotes. The fieldnote excerpt in Figure 4 is from a focus group from a study exploring youth perspectives on the future development of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) legislation for mature minors in Canada. The example illustrates how a researcher could use S&A coding to generate understandings of participants’ engagement and eagerness to discuss a complex topic.

Figure 4.

Example of fieldnote excerpts with Summary and Analysis codes.

We have found that having at least two researchers involved in the S&A process is important; for example, a research assistant (RA) and a supervising team member. For example, the RA who wrote the fieldnotes in Figure 4 did initial coding with close supervisor’s assistance and review for the first few data units. As the process continued, less supervision was needed.

Development of Micro Themes

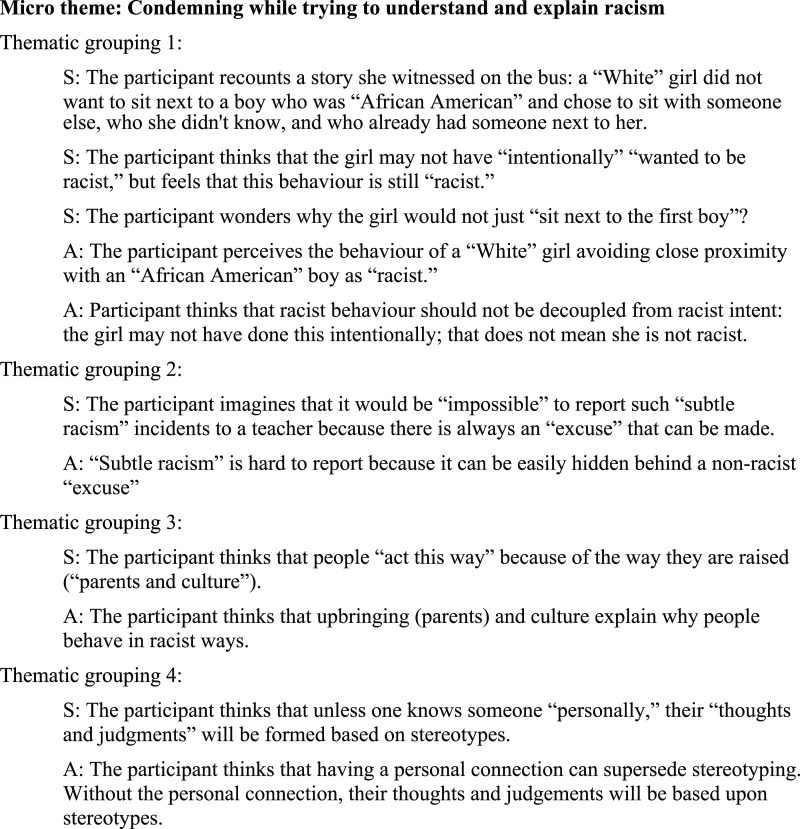

When the coding is finished, we then look for commonalities across a data unit (e.g. one participant’s interview and accompanying fieldnotes; one focus group and accompanying fieldnotes; a participant-observation session). To do so, we extract our codes from the transcript or fieldnote (using the cut and paste feature of our word-processing program) and group them into what we call Micro themes. A Micro theme needs at least 2 S&A codes; it will often have many more. For example, in an ethnographic study exploring the everyday moral experiences of children and youth, all codes relating to one student’s experience witnessing racism at school were sorted into ‘thematic groupings’, and four of these groupings coalesced into one Micro theme, as presented in Figure 5. Figure 6 presents additional examples of Micro themes from this same data unit. One data unit can easily generate over 100 Micro themes.

Figure 5.

Example of a Micro theme with accompanying Summary and Analysis codes.

Figure 6.

Micro theme examples from one data unit.

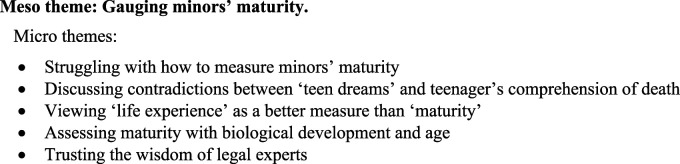

Development of Meso Themes

In the next step, the Micro themes are grouped into Meso themes. To do so, we look for commonalities among the list of Micro themes. For example, in the focus group study exploring youth perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying mentioned above, the analysis of one focus group produced the Meso theme in Figure 7, built from the included list of Micro themes.

Figure 7.

Meso theme with accompanying Micro themes.

The focus group from which these themes were developed was 2 hours in length. Our analysis generated 18 Meso themes. As suggested for the S&A coding, we recommend having at least two team members do this theme development to ensure discussion and reflection is built into the process. Having the same team members lead the majority of the steps is preferable given their increasing familiarity with the data.

Generation of Narrative Syntheses

After the Meso themes are developed, we write a comprehensive Narrative Synthesis of each data unit. In writing the Narrative Synthesis, we follow the advice of qualitative research guru, Margarete Sandelowski, in that we leave the methodological scaffolding behind so that the analytic method (e.g. the language of ‘codes’ and ‘themes’) does not distract from the presentation of the results (Sandelowski, 2007). So, while the Micro and Meso themes continue as scaffolding, they are not used as headings or subheadings.

The Narrative Synthesis includes all the Meso themes with illustrative examples from the corresponding Micro themes and S&A codes. Each Narrative Synthesis aims to provide a rich accounting of the data unit; for example, a participant interview with accompanying fieldnotes. These Narrative Syntheses are typically up to 5 single-spaced pages in length. In writing the Narrative Synthesis, we attend to the philosophical foundation of hermeneutics in that we are careful to ensure that salient data segments are integrated into – yet not lost within – the larger narrative. As described by Crist and Tanner (2003) regarding hermeneutic phenomenology, ‘Within the circular process, narratives are examined simultaneously with the emerging interpretation, never losing sight of the informant’s particular story and context’ (Crist & Tanner, 2003, p. 203). Also drawing on our ethnographic commitment, the Narrative Synthesis process seeks to avoid the fragmentation that thematic analysis can impose on data (Atkinson, 1992).

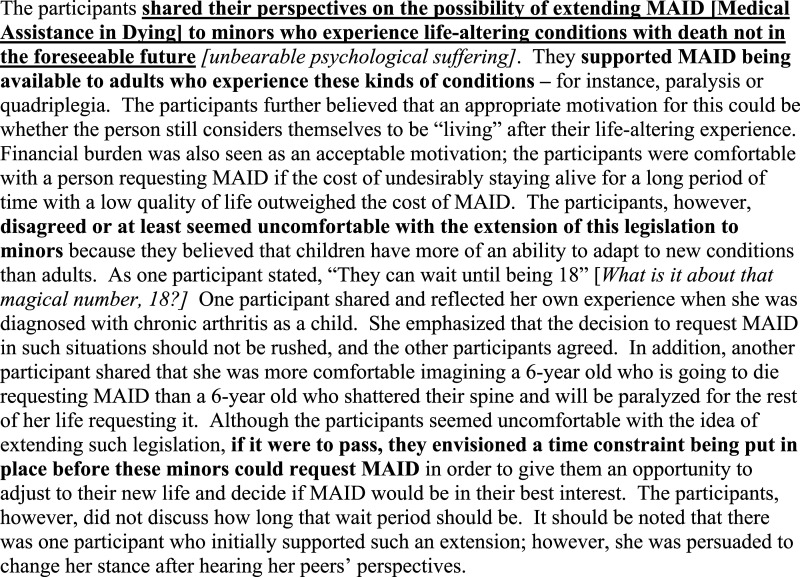

The overall goal of the Narrative Synthesis is to generate an account of the data that responds to the study’s research question. For example, the research question in the Medical Assistance in Dying study mentioned above was: What are young people’s perspectives about Medical Assistance in Dying legislation and its potential extension to include ‘mature minors’ in Canada? Thus, our Narrative Synthesis was driven by a need to capture and unpack the perspectives of young people. With attention to study integrity, at this point in the analytic process it is important for team members who have not yet been actively involved to review and comment on the Narrative Syntheses.

We have developed a style of writing Narrative Syntheses using specific punctuation and formatting features of our word-processing software (e.g. italics, bold, coloured text, and square brackets). We use this formatting to stay attentive to the work completed in the three previous steps of SAMMSA. An example from a focus group in our study on Medical Assistance in Dying is displayed in Figure 8. The reader can follow the formatting and punctuation used in this example with the following key (tailored for black and white printing):

• Quotations marks are used to signal verbatim text from the S codes.

• Square brackets with italics are analytic thoughts and musings from the A codes.

• Bolded text is a rendition of Micro themes.

• Underlined bolded text captures a Meso theme.

Figure 8.

Narrative Synthesis excerpt.

This excerpt also demonstrates the hermeneutic, participatory, and ethnographic roots of SAMMSA. Specific to hermeneutics, the intentional focus on ‘part/whole’ relationships can be seen, for example, via the participant who recounted her experience with chronic arthritis followed by the group’s shared understandings about safeguards (e.g. time constraints). Moving forward in this style of analysis would require attention to other ‘parts’ and ‘wholes,’ namely the other focus groups with their unique participants, as well as ‘young people’ more generally (i.e. as a community with specific values, ideas, and concerns). Adding ethnographic analysis, the ‘whole’ could also reference institutions, reflecting on if and how youth are implicated (e.g. the justice system and the healthcare system).

The ethnographic concern for data holism comes through in the design of this particular study: our data units included both a transcript of each focus group as well as fieldnotes generated by both the facilitator and a research assistant focused on within-group social interactions and providing an opportunity for theoretical reflections, including transversal reflections across the entire data set. In the data segment in Figure 8, ethnographic analysis is also evident when following forward how one speaker evolved their own perspective in line with the culture of the focus group they were in.

Finally, the participatory piece is conveyed in the design of this study: the leader of the focus group was a youth himself. Further, our preliminary analysis was shared with a youth advisory council (https://www.mcgill.ca/voice/team/voice-youth-advisory-council-yac) for feedback which helped move the final analysis forward, and our manuscript was then shared again with this group prior to submission for publication.

Cross-Synthesis Analysis & Interpretation

Cross-synthesis analysis and interpretation is the final step. In this step, we compare and contrast all Narrative Syntheses, sometimes even creating a ‘Synthesis of Narrative Syntheses’ if warranted. In doing so, we focus on generating transversal themes; however, we are also careful to look beyond what is found in common as would be the practice in thematic analysis, actively examining what is unique, discordant, or contradictory. Further, as with developing the Narrative Synthesis, while the data for all the data units are integrated in this final step, a conscious effort is made to recognize and reveal any uniqueness or discord as well.

As mentioned, hallmarks of advanced qualitative research include the development of new knowledge as well as the reflection on, and potential expansion of, prior knowledge. At this point, we purposefully reflect on the frameworks that we brought into the study and, using the ‘theory in, theory out’ wisdom of ethnography, reflect on how our analyses challenge our frameworks. For example, in our study of dental education in which we used the ADKAR framework, our A codes noted limits in ADKAR around ethical tensions. Therefore, in our analysis, we considered ways to tailor ADKAR for our own curricular reform.

Final Thoughts

While the five steps in SAMMSA are linear, this analytic method is meant to be iterative and reflexive. For example, we encourage researchers to reflect on how their research questions can tailor the SAMMSA process, as well as how the analytic process can illuminate new questions. It is not uncommon in qualitative research to realize during analysis that your data are answering a slightly different research question – or additional questions – than you had originally intended. To ensure such opportunities for reflexivity, we recommend that at least two researchers be involved at each stage of the process, preferably with one as a constant presence throughout the entire five steps. Bringing in additional team members to provide fresh insights and to question trains of thought is always helpful.

There are inherent strengths and limitations in any analytic process; in the words of sociologist, Lynd, ‘every way of seeing is a way of not seeing’ (Lynd, 1999 (1958), p. 16). Strengths of SAMMSA include its theoretical foundation in hermeneutics and ethnography, ensuring careful grounding in rich traditions of qualitative inquiry and thus countering simplistic thematic analysis and the ‘bare bones’ reports that generic approaches produce. Further, SAMMSA’s clear path through the analytic process brings a transparency to help explicate the intensity required for quality qualitative analysis; this clarity can be useful for teaching and supporting qualitative research proposals to convey the time and effort required for true ‘quality’ analysis. And finally, we believe that SAMMSA has the potential to enhance the quality of all qualitative analysis; our work to date has begun to demonstrate its utility in multiple methodologies with a variety of data generation methods (Kim et al., 2021; Mellett & Macdonald, 2022).

Notwithstanding these strengths, a limitation is that SAMMSA is labour intensive; as such, we recommend it more for studies that intend to be more interpretive than descriptive. Thus, some approaches – for example, mixed methods research with more descriptive intent, or studies with tight timelines – may not be as amenable to incorporating SAMMSA. However, we also invite readers to try tailoring SAMMSA to their own projects, goals, and timelines and to let us know how the process unfolds.

Conclusion

We have written this article to share a novel approach to qualitative data analysis with the qualitative research community. SAMMSA offers qualitative researchers with another tool for the toolbox, helping to generate rich, integrative, and interpretive analyses from a variety of qualitative data sources. We also believe this article may benefit non-qualitative audiences and those new to qualitative inquiry as we have endeavored to make explicit the efforts required to do justice to qualitative data. We will continue teaching this method through our local workshops and graduate teaching, adapting the process to each new study and reflecting back on the core tenets. We look forward to feedback from the readers to help continuously refine SAMMSA.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the MEM holds the J&W Murphy Foundation Endowed Chair in Palliative Care Research; SS was supported as a research assistant by an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant number: 239025).

Ethical Approval: This manuscript is a description of a methodological advancement. Thus, it did not require an ethical board approval. The data used as examples in this manuscript have been adapted from our own prior studies. While these examples are true to the spirit of the prior studies, the data have been re-written both to be anonymous and to best demonstrate the points made in this paper. Thus, they are not verbatim from transcripts, nor do they reveal any of the participant identifier from our prior studies.

ORCID iDs

Mary Ellen Macdonald https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0581-827X

Franco A. Carnevale https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7255-9979

References

- Atkinson P. (1992). The ethnography of a medical setting: Reading, writing, and rhetoric. Qualitative Health Research, 2(4), 451–474. 10.1177/104973239200200406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caelli K., Ray L., Mill J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(2), 1–13. 10.1177/160940690300200201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale F. A., Collin-Vézina D., Macdonald M. E., Ménard J.-F., Talwar V., Van Praagh S. (2021). Childhood ethics: An ontological advancement for childhood studies. Children & Society, 35(1), 110–124. 10.1111/chso.12406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crist J. D., Tanner C. A. (2003). Interpretation/analysis methods in hermeneutic interpretive phenomenology. Nursing Research, 52(3), 202–205. 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin J. M., Gladstone B. (2020). “Value-adding” analysis: Doing more with qualitative data. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. 10.1177/1609406920949333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eldh A. C., Årestedt L., Berterö C. (2020). Quotations in qualitative studies: Reflections on constituents, custom, and purpose. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–16. 10.1177/1609406920969268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt J. (2006). ADKAR: A model for change in business, government, and our community. Prosci Learning Centre Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M. R., Carnevale F. A. (2011). Moral experience: A framework for bioethics research. Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(11), 658–662. 10.1136/jme.2010.039008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. N., Lebond Rouleau E., Carnevale F., Whiteduck G., Chief D., Macdonald M. E. (2021). Anishnabeg children and youth's experiences and understandings of oral health in rural Quebec. Rural and Remote Health, 21(2), 6365–6365. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/6365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynd H. M. (1999, 1958). On shame and the search for identity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mellett J., Macdonald M. E. (2022). Medical assistance in dying in hospice: A qualitative study. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montreuil M., Carnevale F. A. (2018). Participatory hermeneutic ethnography: A methodological framework for health ethics research with children. Qualitative Health Research, 28(7), 1135–1144. 10.1177/1049732318757489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykhalovskiy E., Eakin J., Beagan B., Beausoleil N., Gibson B. E., Macdonald M. E., Rock M. J. (2018). Beyond bare bones: Critical, theoretically engaged qualitative research in public health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 109(5–6), 613–621. 10.17269/s41997-018-0154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippi J., Lauderdale J. (2017). A guide to field notes for qualitative research: Context and conversation. Qualitative Health Research, 28(3), 381–388. 10.1177/1049732317697102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (2007). Words that should be seen but not written. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(2), 129–130. 10.1002/nur.20198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedlikowski S., Van Praagh S., Shevell M., Carnevale F. A. (2022). Agency in everyday life: An ethnography of the moral experiences of children and youth. Children & Society, 36(4), 661–676. 10.1111/chso.12524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. (1971). Interpretation and the sciences of man. Review of Metaphysics, 25(1), 3–51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20125928 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. (2004). Modern social imaginaries. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonova S., Jessani A., Girard F., Macdonald M. E., De Souza G., Tam L., Nguyen Ngoc C., Morin N., Aggarwal N., Schroth R. J. (2020). The Canadian core cariology curriculum: Outcomes of a national symposium. Journal of Dental Education, 84(11), 1245–1253. 10.1002/jdd.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou K., Barnett J., Thorpe S., Young T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 148. 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]