Abstract

Eribulin is a microtubule dynamics inhibitor with tumor microenvironment modulation activity such as vascular remodeling activity. Here, we investigated antitumor and immunomodulatory activities of eribulin and its liposomal formulation (eribulin-LF) as monotherapies or in combination with anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) Ab. The antitumor activity of eribulin or eribulin-LF as monotherapy or in combination with anti–PD-1 Ab was examined in a P-glycoprotein–knockout 4T1 model. Eribulin and eribulin-LF showed stronger antitumor activity in immunocompetent mice compared with immunodeficient mice, indicating that they have immunomodulatory activity that underlies its antitumor activity. Combination therapy of eribulin and eribulin-LF with anti–PD-1 Ab showed antitumor activity, and the combination activity of eribulin-LF with anti–PD-1 Ab was observed at a lower dose and longer interval of administration compared with that using eribulin. To examine the immunomodulatory activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF and its underlying mechanisms, we performed flow cytometry, IHC, and gene expression profiling. IHC and flow cytometry revealed that eribulin-LF increased microvessel density and intratumoral populations of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells rather than eribulin. Gene expression profiling demonstrated that eribulin-LF induces IFNγ signaling. Furthermore, IHC also showed that eribulin-LF increased infiltration of CD8-positive cells together with increased CD31-positive cells. Eribulin-LF also increased ICAM-1 expression, which is essential for lymphocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells. In conclusion, eribulin showed combination antitumor activity with anti–PD-1 Ab via immunomodulation due to its vascular remodeling activity, and the liposomal formulation showed improved antitumor activity over the standard formulation.

Introduction

In the last 10 years, large advances have been made in the field of cancer immunotherapy, particularly with respect to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)–based therapy. Several ICIs including the anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) Abs nivolumab and pembrolizumab, the anti–programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) Abs atezolizumab and avelumab, and the anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 Ab ipilimumab have been used for the treatment of various cancers (1). However, ICIs show marked antitumor activity in only restricted populations of patients, meaning the percentage of patients who can potentially benefit from ICIs is limited, and the efficacy of ICI monotherapy is still unsatisfactory (2). For example, because the activities of ICIs rely on interactions with T cells, ICIs generally show poor efficacy against immune “cold” tumors, which are tumors showing a phenotype characterized by exclusion of T cells from the tumor or the absence of T-cell infiltration (2–5). In contrast, immune “hot” tumors have a high level of baseline T-cell infiltration and therefore tend to respond to ICIs (5). Therefore, to improve the clinical efficacy of ICIs, especially against immune-cold tumors, many combination approaches of ICIs with chemotherapy or targeted therapy are under development (3).

Eribulin mesylate (eribulin) is a non-taxane microtubule dynamics inhibitor and first in the halichondrin class of such inhibitors (6–10). Eribulin is approved in many countries, including Japan, United States, and Europe, for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer and of soft-tissue sarcoma or unresectable liposarcoma (11–13). Recently, a phase Ib/II study of eribulin + anti–PD-1 Ab pembrolizumab combination therapy in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (ENHANCE 1) has reported a median overall survival of 16.1 months and a median progression-free survival of 4.1 months in the first- to third-line setting (14). Eribulin shows not only antimitotic activity but also non-mitotic activities such as vascular remodeling activity and reversal of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (15–20). A preclinical study using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in human breast cancer models has demonstrated that eribulin induces vascular remodeling resulting in increased microvessel density (MVD) and increased perfusion in tumor core (17).

Drug delivery system using liposomes is a novel system that the encapsulated drug could accumulate in tumors via an enhanced permeability and retention effect (21). We developed a liposomal formulation in which eribulin mesylate is encapsulated in the interior water phase of polyethylene glycol-coated liposomes (eribulin-LF; ref. 22). As a result of this liposomal encapsulation, eribulin-LF shows an improved pharmacokinetic profile and improved antitumor activity compared with non-encapsulated eribulin in human tumor xenograft mouse models (22, 23). Therefore, eribulin-LF might have greater tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation activity compared with eribulin. Eribulin-LF has been shown to be well tolerated and to show clinical activity in a first-in-human phase I clinical study (24).

Tumor vascular normalization by angiogenesis inhibitors is known to facilitate T-cell infiltration into tumors (25, 26). Several studies suggested that eribulin has immunomodulatory activity (20, 27, 28); however, the mechanistic aspect of immunomodulatory activity of eribulin has not been well studied. Here, we investigated that eribulin and eribulin-LF had immunomodulatory activity and found that eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab combination therapy showed promising antitumor activity by improving the TME via vascular remodeling, which enhanced the activity of the cancer immunotherapy in the immune-cold 4T1 mouse breast cancer model (29, 30). Together, we provide a scientific rationale for the further evaluation of eribulin-LF + PD-1 blockade as a novel combination therapy in clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Compounds

Eribulin mesylate (eribulin, Halaven) and eribulin-LF were manufactured by Eisai Co., Ltd. The main liposome formulation includes hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, and 1,2- distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (22). InVivoMAb anti-mouse PD-1 (CD279) Ab (clone RMP1–14, Bio X Cell, catalog no. BE0146, RRID:AB_10949053) was purchased from Bio X Cell. In the in vivo study, eribulin and eribulin-LF were diluted with physiologic saline solution prior to injection. Anti–PD-1 Ab was diluted with physiologic saline solution for intravenous injection or PBS for intraperitoneal injection.

Cell culture

4T1 mouse breast cancer cells (ATCC, catalog no. CRL-2539, RRID:CVCL_0125) were purchased from the ATCC and cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin. RAG mouse renal adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC, catalog no. CCL-142, RRID:CVCL_3575) were purchased from the ATCC and cultured in EMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin. Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated from a human umbilical cord by methods described previously (31–33) and cultured on type-I collagen–coated plates in EGM-2 medium (Lonza) supplemented with EGM-2 SingleQuots except for hydrocortisone. All cell lines were confirmed to be negative for Mycoplasma by using a MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, catalog no. LT07–318) and were authenticated by means of short tandem repeat profiling (ATCC). All experiments were performed within 1 month after thawing early-passage cells.

Establishment of P-glycoprotein–knockout 4T1 cell lines

To knockout (KO) the mouse Abcb1a and Abcb1b genes, which encode P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a CRISPR/Cas9 system was used. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplementary Methods. This approach afforded five P-gp-KO clonal 4T1 cell lines that were designated 4T1#28, 4T1#31, 4T1#38, 4T1#45, and 4T1#54.

In vivo antitumor activity study

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and carried out in accordance with the Animal Experimentation Regulations of Eisai Co., Ltd.

To generate a subcutaneous tumor model (s.c. model), 4T1#31 cells [1 × 106 cells in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS)] were subcutaneously inoculated into the right axillary region of 5- to 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (BALB/cAJcl; CLEA Japan; RRID:IMSR_JCL:JCL:mIN-0005) or BALB/cnu/nu mice (BALB/cSlc-nu/nu; Japan SLC; RRID:MGI:6360654). To generate an orthotopic transplantation model, 4T1#28 or 4T1#31 cells (1 × 106 cells in HBSS) were orthotopically inoculated into the mammary fat pad of 5- to 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (BALB/cAnNCrlCrlj; Charles River Laboratories Japan; RRID:MGI:6323059). When the mean tumor volume (TV) reached 50 to 120 mm3, mice were randomly allocated to treatment groups (n = 5–8 per group) and treatment with eribulin or eribulin-LF, anti–PD-1 Ab, or their combination was started (designated day 1). Eribulin and eribulin-LF were administered by intravenous injection via the tail vein on a Q7D×2 (every 7 days for 2 doses) or Q4D×3 schedule. Anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/head) was administered by intravenous injection on a Q7D×2 schedule in the s.c. model or by intraperitoneal injection on a Q3D×10 or Q3D×8 schedule in the orthotopic model. The control group received no treatment after confirmation that the vehicle solution and the isotype control IgG (InVivoMAb rat IgG2a isotype control, anti-trinitrophenol, clone 2A3; Bio X Cell, catalog no. BE0089, RRID:AB_1107769) did not have any antitumor activities and were comparable with nontreatment (Supplementary Fig. S1a). We also confirmed that 1.0 mg/kg eribulin (Q4D×3, i.v.) + isotype control IgG (200 μg/head; Q3D×9, i.p.) combination therapy did not show enhanced antitumor activity compared with eribulin monotherapy (Supplementary Fig. S1b).

To generate a subcutaneous RAG tumor model, in vivo–adapted RAG cells (ref. 34; 2.5 × 106 cells in HBSS) were subcutaneously inoculated into the right axillary region of 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (BALB/cAnNCrlCrlj). When the mean TV reached 80 to 90 mm3, mice were randomly allocated to treatment groups (n = 10 per group) and treatment with eribulin-LF, anti–PD-1 Ab, or their combination was started (designated day 1). Eribulin-LF was administered by intravenous injection on a Q7D×3 schedule. Anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/head) was administered by intraperitoneal injection on a Q3D×7 schedule.

Tumor size was measured twice each week, and the length and width of the tumor were measured with a caliper. TV was estimated by using the formula TV = 0.5 × (width2 × length). The relative tumor volume (RTV) was calculated by using the formula RTV = TVt/TV1, where TVt is the volume on day t after the start of treatment and TV1 is the volume on day 1. The percentage of ΔT/C (% of control for Δgrowth) was calculated by using the formula ΔT/ΔC × 100%, where ΔT and ΔC are the changes in RTV (Δgrowth) for the drug-treated and non-treated control groups, respectively. In the case of a reduction of TV, ΔT/C was calculated by using the following formula: ΔT/C = (RTVt − RTV1)/RTV1 × 100%, where RTVt is the RTV on day t and RTV1 is the RTV on day 1. The best overall response was determined by comparing the TV change on day t with the baseline volume on day 1. The formula ΔTVt = (TVt – TV1)/TV1 × 100% was used to calculate the percentage change from baseline, and the best overall response was the minimum value of ΔTVt for t ≥ day 8. Tumor response was evaluated on the basis of the modified RECIST criteria for mouse studies, as described previously (35–37). The best overall response less than −95% was defined as a complete response.

IHC

BALB/c mice bearing 4T1#31 subcutaneous tumor were treated with eribulin or eribulin-LF, anti–PD-1 Ab, or their combination (n = 7–8 per group). All agents were administered by intravenous injection via the tail vein on day 1. Tumors were resected on day 11, fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Detailed methods for the IHC analysis are provided in the Supplementary Methods. In short, tissue sections were stained with anti-mouse CD31 Ab (clone SZ31; Dianova catalog no. DIA-310, RRID:AB_2631039) and/or anti-mouse CD8α Ab (clone D4W2Z; Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 98941, RRID:AB_2756376). Stained slides were scanned with an Aperio AT2 (Leica Biosystems; RRID:SCR_021256) or NanoZoomer S60 Digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics; RRID:SCR_022537), and whole tissue was analyzed by using the HALO image analysis platform (Indica Labs; RRID:SCR_018350).

Flow cytometric analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Mice bearing 4T1#31 subcutaneous tumor were treated with eribulin or eribulin-LF, anti–PD-1 Ab, or their combination (n = 7–12 per group). All agents were administered by intravenous injection on day 1. Tumor tissues were collected from each mouse on day 11. The smallest tumor in the eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab combination therapy group (TV < 10 mm3) was combined with the second smallest tumor to obtain enough cells for the analysis. Flow cytometric analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) was performed as previously described with slight modifications (38). Detailed methods are provided in the Supplementary Methods. Abs used for the flow cytometric analysis were listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, and the gating strategy was shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

nCounter and gene set enrichment analysis

Mice bearing 4T1#31 subcutaneous tumor were treated with eribulin-LF, anti–PD-1 Ab, or their combination (n = 10 per group). Both agents were administered by intravenous injection on day 1. Tumors were resected on day 8 and total RNA was extracted and purified by using a Maxwell RSC simplyRNA Tissue Kit (Promega). RNA quality was confirmed by using an Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies; RRID:SCR_019398). Purified total RNA was analyzed by using an nCounter PanCancer Mouse Immune Profiling Panel (NanoString Technologies, catalog no. XT-CSO-MIP1-12, RRID:SCR_021712). Data were imported into the nSolver analysis software (version 4.0.70; NanoString Technologies; RRID:SCR_003420) to check the quality, and then normalized on the basis of positive probes and housekeeping genes.

To characterize transcriptome profiles by their co-expressed gene sets, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the CERNO (Coincident Extreme Ranks in Numerical Observations) algorithm (39) in the tmod (40) was performed at Clarivate Analytics. Detailed methods for the GSEA and IFNγ signature score are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Enrichment of vascular endothelial cells and flow cytometric analysis

Mice bearing 4T1#31 subcutaneous tumor were treated with eribulin-LF (n = 10 per group). Eribulin-LF was administered by intravenous injection on day 1. In this experiment, two randomly selected tumors were combined into one sample to ensure enough cells were obtained for the analysis, resulting in n = 5 per group. Detailed methods for the enrichment of vascular endothelial cells (EC) and staining are provided in the Supplementary Methods. Abs used for the flow cytometric analysis were listed in Supplementary Table S3 and the gating strategy was shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The stained cells were analyzed with a BD FACSymphony A5 cell analyzer (BD Biosciences; RRID:SCR_022538) and the data were analyzed by using the Cytobank software (Cytobank Inc.; RRID:SCR_014043) to quantify the expression level of ICAM-1 on CD31+ vascular ECs.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism v9.0.2 or v9.3.1 software (GraphPad Prism Software, Inc.; RRID:SCR_002798). The unpaired t test, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test or Tukey multiple-comparisons test, or two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test or Tukey multiple-comparisons test was used to confirm statistical significance. For the statistical analysis of tumor response frequency, Fisher exact test was used. In all tests, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Antitumor activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF in immunodeficient versus immunocompetent mice

To enable us to investigate the contribution of the immunomodulatory activity of eribulin to its antitumor activity, we established a mouse syngeneic model using the mouse breast cancer 4T1 cell line, which is an immune-cold tumor cell line that does not respond to anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (29, 30). A previous report demonstrated that antitumor activity of eribulin (ΔT/C value) was associated with its vascular remodeling activity (20). Another report demonstrated that parental 4T1 cells show low sensitivity to eribulin in vivo due to high P-gp expression (17) because eribulin is a substrate of P-gp (41, 42). Thus, to investigate overall immunomodulatory activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF including direct cytotoxic activity against cancer cells, we established five clonal P-gp-KO 4T1 cell lines by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, and then confirmed that these cell lines were sensitive to eribulin by in vitro cell growth inhibition assay (Supplementary Fig. S4a and S4b). We also confirmed that these cells expressed an undetectable level of P-gp by Western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4c). Infiltration of CD8+ cells into tumors tended to be slightly increased only in 4T1#31 tumor compared with parental 4T1 tumor (Supplementary Fig. S4d).

Next, we evaluated the antitumor activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. We constructed an s.c. transplantation model using the P-gp-KO 4T1 clones, 4T1#31. When the average TV reached 80 to 100 mm3, the mice were treated with eribulin or eribulin-LF (0.3 mg/kg Q7D×2; i.v.). Eribulin and eribulin-LF showed significant antitumor activity and eribulin-LF was stronger than eribulin in both the immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S5a). In addition, we found that the ΔT/C value in the immunocompetent mice was significantly lower than that in the immunodeficient mice (Fig. 1B). Together, these results demonstrate that both eribulin and eribulin-LF have immunomodulatory activity, but eribulin-LF have stronger immunomodulatory activity than eribulin, and that this activity contributes to its antitumor activity.

Figure 1.

Antitumor activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF in immunodeficient versus immunocompetent mice. A, Antitumor activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF in 4T1#31 subcutaneous transplantation model in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. When the average TV reached 80 to 100 mm3, tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with eribulin (Eri) or eribulin-LF (Eri-LF) at 0.3 mg/kg on a Q7D×2 (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as mean + SEM. **, P < 0.01 and ****, P < 0.0001 by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons test using log-transformed values, and statistical results of the difference of TV on the indicated days are shown. B, Comparison of the antitumor activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. The ΔT/C value (% of control for Δgrowth) on the last day of measurement was calculated (n = 6 per group). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons test.

To eliminate the possibility that these difference in antitumor activity related to pharmacokinetic profile in these mice, we compared plasma levels of eribulin and eribulin-LF between immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice (Supplementary Fig. S6a). Clearance of eribulin and eribulin-LF was equivalent between immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice, demonstrating that observed difference in antitumor activity in these mice is not related to the difference of pharmacokinetic profile between immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. To address the reason why improved antitumor activity of eribulin-LF versus eribulin, we compared concentrations of eribulin in tumor tissue of 4T1#31 s.c. transplantation model between eribulin-treated and eribulin-LF–treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S6b). Concentration of eribulin was highest at 0.5 hours after administration, and then gradually decreased in eribulin-treated mice. In contrast, concentration of eribulin gradually increased until 8 to 24 hours after administration in eribulin-LF–treated mice, demonstrating that eribulin-LF was accumulated into tumor, and this accumulation should contribute improved antitumor activity of eribulin-LF.

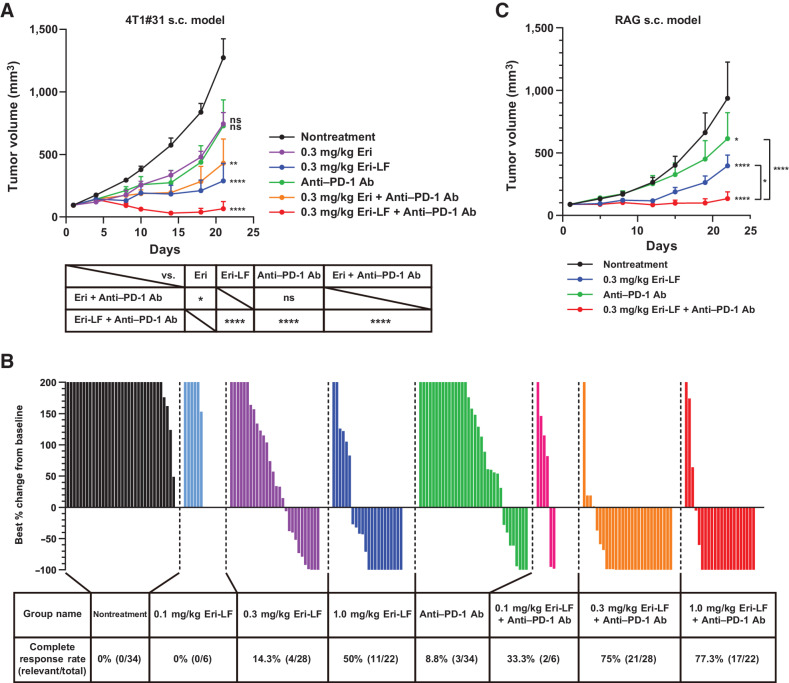

Antitumor activity of eribulin-LF in combination with anti–PD-1 Ab

The observed immunomodulatory activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF prompted us to test the antitumor activity of eribulin in combination with the ICI, anti–PD-1 Ab. To do this, we constructed an s.c. transplantation model with the 4T1#31 cell line. When the average TV reached 90 to 100 mm3, the mice were treated with eribulin or eribulin-LF monotherapy (0.3 mg/kg Q7D×2; i.v.), anti–PD-1 Ab monotherapy (200 μg/mouse Q7D×2; i.v.), or their combination (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S5b). While combination of eribulin with anti–PD-1 Ab had tendency to enhance antitumor activity compared with each monotherapy, the difference was not significant (vs. anti–PD-1 Ab). In contrast, combination of eribulin-LF with anti–PD-1 Ab significantly enhanced antitumor activity compared with each monotherapy. In the case that we compared each combination antitumor activity, the antitumor activity of 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab showed significantly stronger antitumor activity compared with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin + anti–PD-1 Ab.

Figure 2.

Antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab. A, Antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab or each monotherapy in the 4T1#31 subcutaneous transplantation model. When the average TV reached 90 to 100 mm3, mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were intravenously injected with eribulin (Eri) or eribulin-LF (Eri-LF) in combination or not with anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse) on a Q7D×2 schedule (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as mean + SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001; and ns, not significant by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons test using log-transformed values, and statistical results of the difference of TV on the indicated days are shown. B, Waterfall plots across five independent experiments. The best overall response was calculated by comparing the TV change on day t with the baseline TV on day 1 for t ≥ 8. The best percentage changes from baseline that exceeded 200% are shown as 200% in the plots. C, Antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab in RAG tumors. Mice bearing RAG tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg Eri-LF (intravenously) on a Q7D×3 schedule + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse; intraperitoneally) on a Q3D×7 schedule or with each monotherapy (n = 10 per group). Data are presented as mean + SEM. *, P < 0.05 and ****, P < 0.0001 by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test.

We next evaluated the antitumor activity of eribulin-LF (0.1, 0.3, 1.0 mg/kg) + anti–PD-1 Ab in the 4T1#31 s.c. transplantation model to confirm dose-dependency of this combination (Supplementary Fig. S5c). 0.1 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab combination therapy showed significant antitumor activity compared with nontreatment. Furthermore, eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab significantly enhanced antitumor activity compared with each monotherapy and caused tumor regression in 0.3 and 1.0 mg/kg eribulin-LF. These findings indicate that the antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab is dose-dependent.

A waterfall plot of the best TV reduction from days 1 across 5 independent experiments revealed that eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab combination therapy induced strong tumor shrinkage compared with each monotherapy (Fig. 2B). When we evaluated tumor response by using the modified RECIST criteria for mouse studies, the complete response rate in mice treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab (75%) was significantly higher than that in mice treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF (P < 0.0001 by Fisher exact test; 14.3%) or anti–PD-1 Ab (P < 0.0001; 8.8%). The complete response rate in mice treated with 1.0 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab (77.3%) was similar to that with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab (75%).

We also evaluated the antitumor activity of 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab in a mouse renal adenocarcinoma RAG s.c. transplantation model, which is an immune-hot tumor model (34). In this model, the combination therapy also showed significantly stronger antitumor activity compared with nontreatment and each monotherapy (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Fig. S5d).

We next investigated immunomodulatory activity of eribulin in 3 regimens (Supplementary Fig. S7a and S7b). As expected, eribulin (1.0 mg/kg Q4D×3) was most effective in immunocompetent mice. To evaluate combination antitumor activity of eribulin with anti–PD-1 Ab in the same 3 regimens, we next constructed an orthotopic transplantation model with the 4T1#31 cell line (Supplementary Fig. S7c). Eribulin (1.0 mg/kg Q4D×3) + anti–PD-1 Ab showed significantly stronger antitumor activity compared with each monotherapy, inducing complete tumor regression in all mice, demonstrating that a high dose and frequent administration of eribulin are required to obtain acceptable antitumor activity in combination with anti–PD-1 Ab. To eliminate the possibility that these findings were clone-specific, we used another P-gp-KO clone, 4T1#28, to evaluate the antitumor activity of eribulin + anti–PD-1 Ab and comparable results were obtained (Supplementary Fig. S7d). These findings supported that higher and long-lasting exposure of eribulin by eribulin-LF is much better for immunomodulatory activity.

Thus, eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab showed antitumor activity at a lower dose and with a longer interval between eribulin-LF doses compared with combination treatment using eribulin.

Effect of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 ab combination therapy on MVD and TILs

To investigate the mechanism underlying the immunomodulatory activities of eribulin and eribulin-LF, we first examined immunogenic cell death (ICD) activity of eribulin in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S4e and S4f). Treatment with eribulin in 4T1#31 cells increased extracellular ATP and HMGB1, well-known ICD markers, suggesting that eribulin has ICD activity. To investigate the contribution of vascular remodeling activity of eribulin to its immunomodulatory activity in addition to ICD activity, we next examined the effects of eribulin and eribulin-LF on the TME by evaluating MVD and TILs using tumor tissues collected from treated mice. Tumor collection was performed as shown in Fig. 3A: mice bearing 4T1#31 tumor were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin or eribulin-LF, anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse), or their combination on day 1 (only 1 injection; intravenously) when the average TV had reached 60 to 120 mm3, and tumors were collected on days 8 or 11. It is reported that eribulin has vascular remodeling activity that results in increased MVD and tumor vascular perfusion in the tumor core (17). In the collected tumor, both eribulin and eribulin-LF significantly increased MVD compared with nontreatment, and the increase with eribulin-LF was significantly higher than that with eribulin (Fig. 3B and C). We also evaluated the MVD in mice treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab, and the addition of anti–PD-1 Ab to the eribulin-LF monotherapy did not result in a significant increase in MVD (Fig. 3D and E). Thus, eribulin and eribulin-LF both show vascular remodeling activity, but eribulin-LF shows superior vascular remodeling activity compared with that of eribulin on day 11.

Figure 3.

Effect of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab on MVD and TILs. A, Scheme of tumor sampling. When the average TV reached 60 to 120 mm3, immunocompetent BALB/c mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin or eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse) or each monotherapy on day 1 (only 1 injection; intravenously). Tumors were collected on day 8 or day 11 from each mouse and used for the following analyses. FCM, flow cytometry. B and C, Eribulin-LF has superior vascular remodeling activity compared with eribulin. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin (Eri; intravenously) or eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously). Tumors were collected on day 11, and IHC analysis was performed. B, Representative IHC images showing CD31 staining. Bar, 100 μm. C, MVD in whole tumor tissues was quantified (n = 7–8 per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons test. D and E, Eribulin-LF has vascular remodeling activity. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously) + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse; intravenously) or each monotherapy. Tumors were collected on day 11, and IHC analysis was performed. D, Representative IHC images showing CD31 staining. Bar, 100 μm. E, MVD in whole tumor tissue was quantified (n = 8 per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 and ***, P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. F, Flow cytometric analysis of TILs in 4T1#31 tumors. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin (Eri; intravenously) or eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously). Tumors were collected on day 11, and TILs from dissociated tumor tissue cells were analyzed by flow cytometric analysis (n = 8 per group). T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells were gated as CD3+CD11b− cells, CD4+CD3+CD11b− cells, CD8+CD3+CD11b− cells, and CD49b+CD3− cells, respectively. Data are shown as box plots with Tukey-style whiskers. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparisons test. G, Flow cytometric analysis of TILs in 4T1#31 tumors. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously) + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse; intravenously) or each monotherapy. Tumors were collected on day 11, and flow cytometric analysis of TILs was performed (n = 11–12 per group). T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells were gated as CD3+CD11b− cells, CD4+CD3+CD11b− cells, CD8+CD3+CD11b− cells, and CD49b+CD3− cells, respectively. GzmB+CD8+ T cells were gated as GzmB+ cells in CD8+ T cells. GzmB+NK cells were gated as GzmB+NKp46+CD49b+ cells. Data are shown as box plots with Tukey-style whiskers. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. H and I, Eribulin-LF increased infiltration of CD8+ cells. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously) + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse; intravenously) or each monotherapy. Tumors were collected on day 11 and IHC analysis was performed. H, Representative IHC images showing CD8 staining. Bar, 100 μm. I, CD8+ cell count per unit area of whole tumor tissues was quantified (n = 8 per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, P < 0.01 and ***, P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test.

Because vascular remodeling by eribulin improves blood flow (17), we hypothesized that the observed vascular remodeling increases blood flow in the tumor core, resulting in increased infiltration of TILs. We therefore evaluated the changes in the TIL population after treatment with a single administration of 0.3 mg/kg eribulin or eribulin-LF (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. S8a). Flow cytometric analysis of TILs using dissociated tumor tissue cells revealed that a single administration of eribulin-LF significantly increased the populations of T cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells compared with nontreatment, suggesting that these changes contribute to the immunomodulatory activity of eribulin-LF. Furthermore, these changes were significantly superior to those of eribulin, indicating that eribulin-LF has greater immunomodulatory activity compared with eribulin. These population changes of TILs were observed at the same dose at which eribulin-LF was observed to induce vascular remodeling (Fig. 3C), suggesting that vascular remodeling by eribulin-LF contributes to these favorable immune cell population changes.

We next evaluated the changes in the TIL population after administration of 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab or each monotherapy (Fig. 3G; Supplementary Fig. S8b). Again, eribulin-LF monotherapy significantly increased the populations of T cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and NK cells compared with nontreatment. In addition, the activated GzmB+CD8+ T-cell population showed an increasing trend and the activated GzmB+ NK-cell population was significantly increased by eribulin-LF monotherapy. Anti–PD-1 Ab monotherapy also increased these populations compared with nontreatment. Furthermore, the population changes of T cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and GzmB+CD8+ T cells with eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab were significantly superior with those of nontreatment, and eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab significantly increased NK and GzmB+ NK cells compared with each monotherapy.

To further validate the induction of CD8+ T cells by eribulin-LF, we performed an IHC analysis (Fig. 3H and I). The CD8+ cell count per unit area was significantly increased by eribulin-LF monotherapy and eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab combination therapy compared with nontreatment, demonstrating that eribulin-LF induces infiltration of CD8+ T cells into tumor. In contrast, anti–PD-1 Ab monotherapy did not increase the CD8+ cell count compared with nontreatment.

These results demonstrate that eribulin-LF increases the cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell and NK-cell populations in tumor tissue and increases MVD at the same dose.

Effect of eribulin-LF on immune-related gene expressions

To further understand the mechanism underlying the immunomodulatory activity of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab, we performed a gene expression analysis by using the nCounter platform followed by a GSEA. We used the immune response category annotations provided by NanoString and the genes were classified into 30 gene sets based on those annotations. We performed the GSEA using the CERNO algorithm (39, 40). For eribulin-LF monotherapy, the top five gene set categories based on P values were IFN, senescence, basic cell functions, Toll-like receptor, and innate in this order (Fig. 4A). Among these categories, the IFN gene set was the most enriched for eribulin-LF monotherapy and it was also highly enriched (top quartile) for eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab (Fig. 4A). The expressions of the 40 genes included in the IFN gene set were visualized by means of a heat map, which revealed characteristic upregulation of specific genes with eribulin-LF treatment (Supplementary Fig. S9), indicating that eribulin-LF induces IFN signaling. In contrast, the IFN gene set was not enriched for anti–PD-1 Ab monotherapy.

Figure 4.

Effect of eribulin-LF on immune-related gene expression. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously) + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse; intravenously) or each monotherapy (n = 10 per group). Tumors were collected on day 8, and total RNA was extracted and analyzed by using an nCounter PanCancer Mouse Immune Profiling Panel. A, GSEA. GSEA was performed by using the CERNO algorithm, and P values were calculated by using the CERNO test. We used the immune response category annotations provided by NanoString, and the genes were classified into 30 gene sets based on their annotations. In the figure, the 30 gene-set categories are shown sorted on the basis of the P values for the 0.3 mg/kg Eri-LF group. *, P < 0.05. #adjusted P < 0.05. B, IFNγ signature score was increased by eribulin-LF. IFNγ signature score was calculated using the gene expression data determined by using the nCounter PanCancer Mouse Immune Profiling Panel. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test.

Because the IFN signature was enriched by eribulin-LF treatment, we calculated IFNγ signature scores for the treatments (43). Eribulin-LF monotherapy and eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab combination therapy showed comparable IFNγ signature scores that were significantly higher than that of nontreatment (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the score for anti–PD-1 Ab monotherapy was comparable with that for nontreatment. Thus, we concluded that eribulin-LF induces IFNγ signaling.

Correlation between infiltration of CD8+ cells into tumors and vascular remodeling by eribulin-LF

To evaluate the correlation between infiltration of CD8+ cells into tumors and vascular remodeling with eribulin-LF, we performed CD8/CD31 double staining. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumor were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse) or each monotherapy on day 1 (intravenously) when the average TV reached 60 to 120 mm3, and tumors were collected on day 11. In the tumors resected from mice that received nontreatment or anti–PD-1 Ab monotherapy, both CD31+ vascular ECs and CD8+ cells were located mainly at the tumor rim (Fig. 5). However, in the tumors that received eribulin-LF monotherapy or eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab, the numbers of CD31+ vascular ECs were clearly increased in the tumor core, and in accordance with the increased CD31+ cells in the core, infiltration of CD8+ cells into the core was also increased. These data strongly suggest a correlation between induction of CD8+ T-cell infiltration and vascular remodeling by eribulin-LF, especially at the tumor core.

Figure 5.

Correlation between infiltration of CD8+ cells into tumor and vascular remodeling by eribulin-LF. Representative IHC images of CD8/CD31 double staining. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously) + anti–PD-1 Ab (200 μg/mouse; intravenously) or each monotherapy. Tumors were collected on day 11, and IHC analysis was performed. Tissues were stained with anti-CD8α (green) and anti-CD31 (red) Abs, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The dashed line marked “C” indicates the tumor core. Bar, 100 μm.

Effect of eribulin-LF on expression of ICAM-1 in vascular ECs

Because eribulin-LF increased infiltration of T cells into tumors along with increased MVD, we evaluated whether eribulin or eribulin-LF affect vascular functions such as the lymphocyte adhesive property of vascular ECs. First, we evaluated the induction of ICAM-1, which plays an essential role in lymphocyte adhesion on vascular ECs, by eribulin in HUVECs at the protein level. HUVECs were treated with the IC50 concentration (0.5 nmol/L) or the 10 × IC50 concentration (5 nmol/L) of eribulin for 48 hours and protein extracted from the treated cells was analyzed by Western blotting. The expression of ICAM-1 was dose-dependently increased by eribulin in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S3a), which is consistent with a previous report that eribulin induces mRNA expression of ICAM-1 in HUVECs (44).

We then evaluated the effect of eribulin-LF on the expression level of ICAM-1 in vascular ECs in vivo using 4T1#31 tumor tissues. To analyze the expression level of ICAM-1, tumor tissues were dissociated into a single-cell suspension. Using the obtained cell suspension, CD45+ leukocytes were depleted by negative selection and CD31+ ECs were enriched by positive selection by using magnetic-activated cell sorting technology (Fig. 6A). After enrichment of CD31+ vascular ECs, the expression level of ICAM-1 on vascular ECs was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis. The expression level of ICAM-1 on CD31+ vascular ECs was significantly increased by eribulin-LF treatment compared with nontreatment (Fig. 6B and C), suggesting that induction of ICAM-1 expression on vascular ECs is one mechanism through which eribulin-LF increases the infiltration of TILs.

Figure 6.

Effect of eribulin-LF on expression of ICAM-1 in vascular ECs. Eribulin-LF induced ICAM-1 expression in vascular ECs in 4T1#31 tumors. Mice bearing 4T1#31 tumors were treated with the indicated dose of eribulin-LF (Eri-LF; intravenously). Tumors were collected on day 8, and CD31+ vascular ECs were enriched by magnetic-activated cell sorting. After enrichment of CD31+ vascular ECs, the expression level of ICAM-1 on vascular ECs was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis. A, Representative dot plots (CD45 vs. CD31). Cell suspensions obtained from tumor tissues (before enrichment) and EC-enriched cell suspensions after magnetic-activated cell sorting (after enrichment) were analyzed by flow cytometric analysis. Vascular ECs were gated as CD31+CD45− cells (blue lines). B, Representative histogram of ICAM-1 expression in the population gated on CD31+ vascular ECs. The gray line represents the isotype control; and the black, blue, and red lines represent ICAM-1 in the nontreatment, 0.3 mg/kg Eri-LF, and 1.0 mg/kg Eri-LF groups, respectively. C, Mean fluorescence intensities (n = 5 per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001 and ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple-comparisons test.

Discussion

The current study provides preclinical evidence that eribulin has immunomodulatory activity and that it has enhanced antitumor activity with anti–PD-1 Ab. The results also show that our liposomal formulation of eribulin, eribulin-LF, has improved immunomodulatory activity and therefore, eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab has better antitumor activity compared with eribulin + anti–PD-1 Ab through achievement of high distribution of eribulin in tumor tissues by liposome formulation. Similar observation was reported for doxorubicin and its liposomal formulation, Doxil (45, 46), supporting our findings.

We used a P-gp-KO clonal 4T1 cell line, 4T1#31, to evaluate the antitumor activity of eribulin or eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab and to elucidate the mechanism underlying the antitumor activity of the combination therapy. Consistent with previous reports (29, 30), 4T1#31 tumor did not respond to anti–PD-1 Ab, demonstrating that P-gp KO did not alter the immune-cold phenotype of 4T1 tumor. In this 4T1#31 tumor, eribulin or eribulin-LF in combination with anti–PD-1 Ab showed marked antitumor activity. Because we demonstrated that eribulin has ICD activity in vitro, we consider that the ICD activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF, at least partly, may contribute the observed immunomodulatory activity in vivo. On the other hand, it is reported that vascular remodeling by eribulin increases MVD and vascular perfusion in tumor core (17). Another report has shown that NK cells contribute to the antitumor activity of eribulin, and that the increase of the NK-cell population in tumor by eribulin could be a result of vascular remodeling (20). In our IHC analysis using CD8/CD31 double staining, eribulin-LF treatment was found to clearly increase the CD31+ vascular ECs, especially in the tumor core (Fig. 5), suggesting that eribulin-LF increases blood flow in tumor core by vascular remodeling. Moreover, eribulin-LF treatment was found to also increase infiltration of CD8+ T cells into tumor core, which is characteristic of the immune-hot-like tumor phenotype. In contrast, in tumor that received no treatment, CD8+ T cells were mainly located at the tumor rim, which is characteristic of the immune-excluded, cold-like phenotype (2–4). These findings suggest that eribulin and eribulin-LF are able to convert immune-cold-like tumors to immune-hot-like tumors by facilitating infiltration of CD8+ T cells and NK cells into tumors by inducing vascular remodeling. Because eribulin is microtubule dynamics inhibitor, effects on vascular ECs and angiogenesis are predicted. Some microtubule destabilizing drugs were reported as vascular disrupting agents (47) that block vascular perfusion. In contrast, eribulin increases vascular perfusion and MVD (17) and the phenomena are defined as vascular remodeling. Thus, vascular disruption and vascular remodeling are substantially difference. Moreover, the concentration in which microtubule destabilizing drugs act as anti-vascular drugs is close to maximum tolerated dose (47); however, 0.3 mg/kg eribulin-LF, mainly used concentration in this study, is very low compared with maximum tolerated dose (2.5 mg/kg), suggesting that eribulin-LF may not have vascular disrupting activity at least in this low concentration. Indeed, vinorelbine, a microtubule destabilizing agent, does not have vascular remodeling activity (20), suggesting vascular remodeling activity and consequent infiltration of CD8+ T cells may be unique activities for eribulin and eribulin-LF.

In the current study, we also demonstrated that eribulin-LF activates IFNγ signaling. IFNγ is a key molecule in the activation of the antitumor immune response and its induction of the T cell–attracting chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 is critical for T-cell and NK-cell trafficking into tumor (48, 49). Thus, activation of IFNγ signaling likely plays a key role in the activity of eribulin-LF to increase infiltration of activated T cells and NK cells into tumor. Moreover, IFNγ also contributes to the efficacy of ICIs (50). Patients harboring tumors that respond to ICIs usually have higher expression scores of IFNγ-related genes compared with those of nonresponders, and IFNγ signature score has been proposed to predict clinical response to ICI-based therapy (43, 50). Therefore, activation of IFNγ signaling by eribulin-LF based on different mechanism from ICIs, could improve patients’ response to ICIs.

Eribulin-LF also increased expression of ICAM-1 on vascular ECs to further increase infiltration of leukocytes into tumor. One possible mechanism underlying the induction of ICAM-1 is activation of the cGAS–STING innate immunity pathway by eribulin (51). A recent report has shown that eribulin induces cGAS–STING–TANK-binding kinase-1 (TBK1)-dependent expression of type I IFN (IFNβ) via the accumulation of cytoplasmic mitochondrial DNA (51). Activation of the cGAS–STING–TBK1 pathway leads to phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), resulting in nuclear translocation of active IRF3, which binds to the promoter of ICAM-1 and induces ICAM-1 expression (52, 53). Together, these reports suggest that eribulin-LF increases cGAS–STING-dependent ICAM-1 expression. The detailed mechanism underlying the upregulation of ICAM-1 in vascular ECs by eribulin-LF was not revealed in the current study; however, we consider that increased expression of ICAM-1 in vascular ECs could contribute to the immunomodulatory activity of eribulin and eribulin-LF.

To estimate the clinical efficacy of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab, the TME alteration by eribulin-LF should be confirmed in clinic and biomarker is required to monitor eribulin-LF activity. Evaluation of vascular remodeling in patients may be a useful candidate as a pharmacodynamic biomarker of eribulin-LF in combination with ICI because it improved T- and NK-cell infiltration in immune-cold tumors. Vascular remodeling may be also a monitoring biomarker or a potential predictive biomarker for eribulin-LF + ICI combination therapy. IFNγ and its related molecules may also be a possible biomarker for eribulin-LF + ICI combination therapy. Further studies are needed to identify the most appropriate biomarkers for use in preclinical and clinical studies of eribulin-LF.

In clinic, eribulin + anti–PD-1 Ab pembrolizumab combination therapy was reported in triple-negative and luminal type breast cancers (14, 54). In this study, we mainly used mouse triple-negative breast cancer 4T1 model and our preclinical results revealed that antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab was better than that of eribulin + anti–PD-1 Ab: current data do not cover combination activity in luminal type breast cancer model. However, this combination of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab was also effective in mouse renal adenocarcinoma RAG model, suggesting that this combination is effective in several tumor types. There might be suitable cancer types for combination of eribulin-LF + anti–PD-1 Ab and further studies are required to identify it.

In summary, our present results suggest that eribulin or eribulin-LF in combination with anti–PD-1 Ab exerts their antitumor activity via three main mechanisms: (i) increased vascular remodeling by eribulin or eribulin-LF, which increases blood flow and infiltration of TILs into tumor core; (ii) induction of ICAM-1 expression in vascular ECs by eribulin-LF to further increase infiltration of T cells into tumor; and (iii) activation of IFNγ signaling by eribulin-LF to increase activated CD8+ T cells. These activities of eribulin and eribulin-LF change the TME into one that is favorable for cancer immunotherapy to work, and eribulin-LF is more effective than eribulin in this regard. A phase Ib/II clinical trial of combination therapy with eribulin-LF plus the anti–PD-1 Ab nivolumab in patients with selected solid cancer is currently ongoing (NCT04078295; ref. 55). The present results provide a scientific rationale for evaluating eribulin-LF + nivolumab as a novel combination cancer immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Fig S1 shows isotype control has no antitumor activity. Fig S2 shows gating strategy for flow cytometric analysis of TILs. Fig S3 shows induction of ICAM-1 by eribulin. Fig S4 shows establishment of P-gp KO cell lines and ICD activity of eribulin. Fig S5 shows dose-dependent antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti-PD-1 Ab. Fig S6 shows PK analysis of eribulin and eribulin-LF in plasma and tumor. Fig S7 shows immunomodulatory activity of eribulin in different 3 regimens. Fig S8 shows TIL population changes not included in the main figures. Fig S9 shows activation of IFN signature by eribulin-LF.

Legends for supplementary figures S1-S9

Supplementary Materials and Methods not included in the main manuscript

Antibody lists used in the flow cytometric analysis

Acknowledgments

The work was financially supported by Eisai Co., Ltd.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the members of Sunplanet Co., Ltd. for their excellent technical support. The authors also thank their colleagues at Tsukuba Research Laboratories of Eisai Co., Ltd. for their fruitful discussions and constructive comments.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Therapeutics Online (http://mct.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

Y. Niwa, K. Adachi, K. Tabata, R. Ishida, K. Hotta, T. Ishida, Y. Mano, Y. Ozawa, and Y. Minoshima report personal fees from Eisai Co., Ltd. during the conduct of the study. Y. Minoshima reports personal fees from Eisai Co., Ltd during the conduct of the study. Y. Funahashi reports personal fees from Eisai Co., Ltd. during the conduct of the study; in addition, Y. Funahashi has a patent for US11083705B2 issued and a patent for US20220117933A1 pending. T. Semba reports personal fees from Eisai Co., Ltd. during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Eisai Co., Ltd. outside the submitted work; in addition, T. Semba has a patent for US11083705B2 issued and a patent for US20220117933A1 pending.

Authors' Contributions

Y. Niwa: Data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft. K. Adachi: Formal analysis, validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. K. Tabata: Investigation, writing–review and editing. R. Ishida: Software, methodology, writing–review and editing. K. Hotta: Investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. T. Ishida: Investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. Y. Mano: Investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. Y. Ozawa: Resources, writing–review and editing. Y. Minoshima: Resources, writing–review and editing. Y. Funahashi: Conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing–review and editing. T. Semba: Conceptualization, investigation, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Vaddepally RK, Kharel P, Pandey R, Garje R, Chandra AB. Review of indications of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors per NCCN guidelines with the level of evidence. Cancers 2020;12:738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu YT, Sun ZJ. Turning cold tumors into hot tumors by improving T-cell infiltration. Theranostics 2021;11:5365–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered, and cold tumors with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18:197–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hegde PS, Chen DS. Top 10 challenges in cancer immunotherapy. Immunity 2020;52:17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti–PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014;515:563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Y, Habgood GJ, Christ WJ, Kishi Y, Littlefield BA, Yu MJ. Structure-activity relationships of halichondrin B analogues: modifications at C.30-C.38. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2000;10:1029–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Towle MJ, Salvato KA, Budrow J, Wels BF, Kuznetsov G, Aalfs KK, et al. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of synthetic macrocyclic ketone analogues of halichondrin B. Cancer Res 2001;61:1013–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swami U, Chaudhary I, Ghalib MH, Goel S. Eribulin: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012;81:163–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith JA, Wilson L, Azarenko O, Zhu X, Lewis BM, Littlefield BA, et al. Eribulin binds at microtubule ends to a single site on tubulin to suppress dynamic instability. Biochemistry 2010;49:1331–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jordan MA, Kamath K, Manna T, Okouneva T, Miller HP, Davis C, et al. The primary antimitotic mechanism of action of the synthetic halichondrin E7389 is suppression of microtubule growth. Mol Cancer Ther 2005;4:1086–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cortes J, O'Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, Blum JL, Vahdat LT, et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician's choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase III open-label randomized study. Lancet 2011;377:914–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donoghue M, Lemery SJ, Yuan W, He K, Sridhara R, Shord S, et al. Eribulin mesylate for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic breast cancer: use of a "physician's choice" control arm in a randomized approval trial. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:1496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schoffski P, Chawla S, Maki RG, Italiano A, Gelderblom H, Choy E, et al. Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: a randomized, open-label, multicenter, phase III trial. Lancet 2016;387:1629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tolaney SM, Kalinsky K, Kaklamani VG, D'Adamo DR, Aktan G, Tsai ML, et al. Eribulin plus pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (ENHANCE 1): a phase Ib/II study. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:3061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kawano S, Asano M, Adachi Y, Matsui J. Antimitotic and non-mitotic effects of eribulin mesilate in soft-tissue sarcoma. Anticancer Res 2016;36:1553–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Niwa Y, Asano M, Nakagawa T, France D, Semba T, Funahashi Y. Antitumor activity of eribulin after fulvestrant plus CDK4/6 inhibitor in breast cancer patient-derived xenograft models. Anticancer Res 2020;40:6699–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Funahashi Y, Okamoto K, Adachi Y, Semba T, Uesugi M, Ozawa Y, et al. Eribulin mesylate reduces tumor microenvironment abnormality by vascular remodeling in preclinical human breast cancer models. Cancer Sci 2014;105:1334–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoshida T, Ozawa Y, Kimura T, Sato Y, Kuznetsov G, Xu S, et al. Eribulin mesilate suppresses experimental metastasis of breast cancer cells by reversing phenotype from epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) to mesenchymal–epithelial transition (MET) states. Br J Cancer 2014;110:1497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ueda S, Saeki T, Takeuchi H, Shigekawa T, Yamane T, Kuji I, et al. In vivo imaging of eribulin-induced reoxygenation in advanced breast cancer patients: a comparison to bevacizumab. Br J Cancer 2016;114:1212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ito K, Hamamichi S, Abe T, Akagi T, Shirota H, Kawano S, et al. Antitumor effects of eribulin depend on modulation of the tumor microenvironment by vascular remodeling in mouse models. Cancer Sci 2017;108:2273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maruyama K. Intracellular targeting delivery of liposomal drugs to solid tumors based on EPR effects. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2011;63:161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu Y, Desjardins C, Saxton P, Lai G, Schuck E, Wong YN. Characterization of the pharmacokinetics of a liposomal formulation of eribulin mesylate (E7389) in mice. Int J Pharm 2013;443:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Asano M, Hyodo K, Yu Y, Schuck E, Matsui J, Ishihara H, et al. [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2015 Apr 18–22; Philadelphia, PA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Cancer Res; 2015;75(15 Suppl):Abstract nr 4543. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evans TRJ, Dean E, Molife LR, Lopez J, Ranson M, El-Khouly F, et al. Phase I dose-finding and pharmacokinetic study of eribulin-liposomal formulation in patients with solid tumors. Br J Cancer 2019;120:379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Y, Yuan J, Righi E, Kamoun WS, Ancukiewicz M, Nezivar J, et al. Vascular normalizing doses of antiangiogenic treatment reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhance immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:17561–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tian L, Goldstein A, Wang H, Ching Lo H, Sun Kim I, Welte T, et al. Mutual regulation of tumor vessel normalization and immunostimulatory reprogramming. Nature 2017;544:250–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miyoshi Y, Yoshimura Y, Saito K, Muramoto K, Sugawara M, Alexis K, et al. High absolute lymphocyte counts are associated with longer overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with eribulin-but not with treatment of physician's choice-in the EMBRACE study. Breast Cancer 2020;27:706–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goto W, Kashiwagi S, Asano Y, Takada K, Morisaki T, Fujita H, et al. Eribulin promotes antitumor immune responses in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Res 2018;38:2929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grasselly C, Denis M, Bourguignon A, Talhi N, Mathe D, Tourette A, et al. The antitumor activity of combinations of cytotoxic chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors is model-dependent. Front Immunol 2018;9:2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu M, Zheng D, Zhang D, Yu P, Peng L, Chen F, et al. Converting immune cold into hot by biosynthetic functional vesicles to boost systematic antitumor immunity. iScience 2020;23:101341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsui J, Yamamoto Y, Funahashi Y, Tsuruoka A, Watanabe T, Wakabayashi T, et al. E7080, a novel inhibitor that targets multiple kinases, has potent antitumor activities against stem cell factor producing human small cell lung cancer H146, based on angiogenesis inhibition. Int J Cancer 2008;122:664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsui J, Wakabayashi T, Asada M, Yoshimatsu K, Okada M. Stem cell factor/c-kit signaling promotes the survival, migration, and capillary tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2004;279:18600–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakagawa T, Matsushima T, Kawano S, Nakazawa Y, Kato Y, Adachi Y, et al. Lenvatinib in combination with golvatinib overcomes hepatocyte growth factor pathway-induced resistance to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor. Cancer Sci 2014;105:723–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adachi Y, Kamiyama H, Ichikawa K, Fukushima S, Ozawa Y, Yamaguchi S, et al. Inhibition of FGFR reactivates IFNgamma signaling in tumor cells to enhance the combined antitumor activity of lenvatinib with anti–PD-1 antibodies. Cancer Res 2022;82:292–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kimura T, Kato Y, Ozawa Y, Kodama K, Ito J, Ichikawa K, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of lenvatinib contributes to antitumor activity in the Hepa1–6 hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancer Sci 2018;109:3993–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gao H, Korn JM, Ferretti S, Monahan JE, Wang Y, Singh M, et al. High-throughput screening using patient-derived tumor xenografts to predict clinical trial drug response. Nat Med 2015;21:1318–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kato Y, Tabata K, Kimura T, Yachie-Kinoshita A, Ozawa Y, Yamada K, et al. Lenvatinib plus anti–PD-1 antibody combination treatment activates CD8+ T cells through reduction of tumor-associated macrophage and activation of the interferon pathway. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamaguchi KD, Ruderman DL, Croze E, Wagner TC, Velichko S, Reder AT, et al. IFNβ-regulated genes show abnormal expression in therapy-naive relapsing-remitting MS mononuclear cells: gene expression analysis employing all reported protein–protein interactions. J Neuroimmunol 2008;195:116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zyla J, Marczyk M, Domaszewska T, Kaufmann SHE, Polanska J, Weiner J. Gene set enrichment for reproducible science: comparison of CERNO and eight other algorithms. Bioinformatics 2019;35:5146–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oba T, Izumi H, Ito KI. ABCB1 and ABCC11 confer resistance to eribulin in breast cancer cell lines. Oncotarget 2016;7:70011–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park Y, Son JY, Lee BM, Kim HS, Yoon S. Highly eribulin-resistant KBV20C oral cancer cells can be sensitized by co-treatment with the third-generation p-glycoprotein inhibitor, elacridar, at a low dose. Anticancer Res 2017;37:4139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DR, et al. IFNγ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2930–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Agoulnik SI, Kawano S, Taylor N, Oestreicher J, Matsui J, Chow J, et al. Eribulin mesylate exerts specific gene expression changes in pericytes and shortens pericyte-driven capillary network in vitro. Vasc Cell 2014;6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rios-Doria J, Durham N, Wetzel L, Rothstein R, Chesebrough J, Holoweckyj N, et al. Doxil synergizes with cancer immunotherapies to enhance antitumor responses in syngeneic mouse models. Neoplasia 2015;17:661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Takayama T, Shimizu T, Lila ASA, Kanazawa Y, Ando H, Ishima Y, et al. Adjuvant antitumor immunity contributes to the overall antitumor effect of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil®) in C26 tumor-bearing immunocompetent mice. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smolarczyk R, Czapla J, Jarosz-Biej M, Czerwinski K, Cichoń T. Vascular disrupting agents in cancer therapy. Eur J Pharmacol 2021;891:173692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Castro F, Cardoso AP, Goncalves RM, Serre K, Oliveira MJ. Interferon-gamma at the crossroads of tumor immune surveillance or evasion. Front Immunol 2018;9:847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Melero I, Rouzaut A, Motz GT, Coukos G. T-cell and NK-cell infiltration into solid tumors: a key limiting factor for efficacious cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2014;4:522–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jorgovanovic D, Song M, Wang L, Zhang Y. Roles of IFNγ in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomark Res 2020;8:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fermaintt CS, Takahashi-Ruiz L, Liang H, Mooberry SL, Risinger AL. Eribulin activates the cGAS-STING pathway via the cytoplasmic accumulation of mitochondrial DNA. Mol Pharmacol 2021;100:309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mao Y, Luo W, Zhang L, Wu W, Yuan L, Xu H, et al. STING-IRF3 triggers endothelial inflammation in response to free fatty acid-induced mitochondrial damage in diet-induced obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:920–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oduro PK, Zheng X, Wei J, Yang Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, et al. The cGAS-STING signaling in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases: future novel target option for pharmacotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B 2022;12:50–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tolaney SM, Barroso-Sousa R, Keenan T, Trippa L, Hu J, Luis IMVD, et al. Randomized phase II study of eribulin mesylate (E) with or without pembrolizumab (P) for hormone receptor–positive (HR plus) metastatic breast cancer (MBC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1004. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yamamoto N, Ida H, Shimizu T, Nakamura Y, Nishino M, Yazaki S, et al. Phase Ib study of a liposomal formulation of eribulin (E7389-LF) + nivolumab (Nivo) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 2021;32:980P. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1 shows isotype control has no antitumor activity. Fig S2 shows gating strategy for flow cytometric analysis of TILs. Fig S3 shows induction of ICAM-1 by eribulin. Fig S4 shows establishment of P-gp KO cell lines and ICD activity of eribulin. Fig S5 shows dose-dependent antitumor activity of eribulin-LF + anti-PD-1 Ab. Fig S6 shows PK analysis of eribulin and eribulin-LF in plasma and tumor. Fig S7 shows immunomodulatory activity of eribulin in different 3 regimens. Fig S8 shows TIL population changes not included in the main figures. Fig S9 shows activation of IFN signature by eribulin-LF.

Legends for supplementary figures S1-S9

Supplementary Materials and Methods not included in the main manuscript

Antibody lists used in the flow cytometric analysis

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.