Abstract

Purpose

The absorbed dose estimation from Voxel-S-Value (VSV) method in heterogeneous media is suboptimal as VSVs are calculated in homogeneous media. The aim of this study is to develop and evaluate new VSV methods in order to enhance the accuracy of Y-90 microspheres absorbed dose estimation in liver, lungs, tumors and lung-liver interface regions.

Methods

Ten patients with Y-90 microspheres SPECT/CT and PET/CT data, six of whom had additional Tc-99m-macroaggregated albumin SPECT/CT data, were analyzed from the Deep Blue Data Repository. Seven existing VSV methods along with three newly proposed VSV methods were evaluated: liver and lung kernel with center voxel scaling (LiLuCK), liver kernel with density correction and lung kernel with center voxel scaling (LiKDLuCK), liver kernel with center voxel scaling and lung kernel with density correction (LiCKLuKD). Monte Carlo (MC) results were regarded as the gold standard. Absolute absorbed dose errors (%AADE) of these methods for the liver, lungs, tumors, upper liver, and lower lungs were assessed.

Results

Liver and tumor’s median %AADE of all methods were <3% for three types of imaging data. In the lungs, however, three recently proposed VSV methods provided median %AADEs of less than 7%, whereas the differences exceeded 20% for existing methods that did not use a lung kernel. LiCKLuKD could achieve median %AADE <2% in the liver, upper liver and tumors, and median %AADE <7% in the lungs and lower lungs in three types of data.

Conclusion

All methods are consistent with MC in the liver and tumors. Methods with tissue-specific kernel and effective correction achieve smaller errors in lungs. LiCKLuKD has comparable results with MC in absorbed dose estimation of Y-90 radioembolization for all target regions.

Keywords: Yttrium-90 microsphere, Tc-99m macroaggregated albumin, Radioembolization, Quantitative imaging, Voxel-S-value

1. Introduction

Radioembolization (RE) with Y-90 microspheres is an effective treatment for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and metastatic tumors in liver [1]. Y-90 resin microspheres (SIR-Sphere, Sirtex, Medical, Sydney, Australia) or glass microspheres (TheraSphere, BTG, Boston Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) are delivered to the tumor via a catheter placed in the hepatic artery. Before Y-90 RE therapy, planar or SPECT/CT scans of Tc-99m macroaggregated albumin (MAA), a surrogate of Y-90 microspheres, are first acquired for treatment planning and patient selection [2]. The maximum injected activity can be calculated by the partition model [3], while the injected activity is calculated by the body surface area method [4] and the standard model [5]. Given the dose constraints to tumor and healthy tissues, the maximum injected activity should be calculated using the MIRD-based partition model. After Y-90 RE, quantitative imaging of Y-90 microspheres using bremsstrahlung SPECT/CT or PET/CT is then acquired to verify the treatment planning [6], [7]. Since microspheres are trapped in the tumor and hepatic arterial microvasculature, only one imaging time point is needed to estimate the time-integrated activity (TIA) from Y-90 imaging, assuming only physical decay afterwards. In addition to the partition model, 3D voxel-level dosimetry methods have recently been shown to be feasible with advantages over conventional 2D models [8], [9] as recommended by EANM [10].

Three methods for absorbed dose conversion are currently available, i.e., local energy deposition (LED) method, Monte Carlo (MC) method and Voxel-S-Value (VSV) method. LED method, which assumes that energy released by decay of the isotope is deposited within the same voxel, is usually used for absorbed dose conversion in Y-90 RE dosimetry [11]. However, Y-90 has a maximum β- energy of 2.28 MeV deposited through a maximum distance of 11 mm in common soft tissues [12] and 44 mm in lungs. Comparing this distance with the common voxel size of emission computed tomography (ECT), i.e., SPECT (2–5 mm) or PET (1–4 mm), for the common system spatial resolution of 6–10 mm and 4–6 mm for recent SPECT and PET systems respectively [13], LED may not be sufficiently accurate for absorbed dose conversion, especially near the heterogeneous organs interface where the cross radiation at voxel-level needs to be considered [14]. The MC approach is currently the gold standard for absorbed dose conversion, applicable for both pre-therapy treatment planning and post-therapy dose verification. However, the VSV approach is proposed as an efficient alternate to the MC approach [15], performing better than LED for cross voxel radiation. VSVs are generated in homogenous media with specific voxel and matrix size using MC simulation, and can be convolved with the TIA map to generate absorbed dose map with high accuracy for soft tissues [16]. A single type of VSV is proven to be unsuitable for all media [17], [18]. Even if multiple VSVs are used for heterogeneous media, respectively, absorbed dose estimation is still compromised in tissues interface, e.g., the liver-lungs and soft tissue-bone interface in Lu-177-based treatment [19]. VSV approach with density correction [17], [20], [21] is proposed to address the limitations of VSV in heterogeneous media but the performance in the liver-lungs interface is still relatively poor [14]. This may affect the tumor absorbed dose estimation, especially when the tumors are located close to the interface, or for the lungs and liver toxicity evaluation in general [22], [23]. Deep learning methods have been successfully implemented for generating heterogeneous VSVs corresponding to patient-specific anatomy [24], [25]. However, it is still computationally intensive to build a VSV dataset for various tissues compositions.

In this study, we proposed three new VSV approaches for dosimetric analysis using Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, Y-90 RE bremsstrahlung SPECT/CT and PET/CT. We evaluated their performance in target volumes-of-interest (VOIs) for Y-90 RE, i.e., the liver, lungs, tumor, and interface regions, including the upper liver and lower lungs along with existing VSV methods.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient data

Pre-therapy and post-therapy imaging data of ten patients treated with Y-90 microspheres from Deep Blue Data Repository were analyzed [26], [27]. Six patients underwent quantitative Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, Y-90 microspheres SPECT/CT and PET/CT imaging, while four patients only underwent quantitative Y-90 SPECT/CT and PET/CT imaging. The detailed imaging protocol and reconstruction parameters were published previously [28], [29]. The Tc-99m-MAA SPECT, Y-90 microspheres SPECT and PET images were acquired with a voxel size of 4.80 × 4.80 × 4.80 mm3, 4.80 × 4.80 × 4.80 mm3 and 4.07 × 4.07 × 3.00 mm3 respectively. A sample patient with three imaging datasets is shown in Fig. 1. Ten liver and 35 lesion contours based on CT images were provided by the database, while lesion contours were not provided for two patients and their lesions were therefore not included in this study. Lungs contours were segmented on CT using ITK-SNAP [30], [31]. In addition, the upper liver and lower lungs regions were segmented by extending a 15 mm slab from the liver-lungs boundary to liver and lungs, respectively, for the absorbed dose analysis. These two boundary regions were analyzed independently, while they were also included in total liver and lungs absorbed dose calculation, respectively. Fig. 1D shows an example of different VOIs for a selected patient.

Figure 1.

Coronal view of sample quantitative (A) Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, (B) Y-90 microsphere bremsstrahlung SPECT/CT, (C) Y-90 microsphere PET/CT images, and (D) various VOIs for one sample patient.

2.2. MC simulation for absorbed dose calculation and VSV generation

GATE v.9.0 was used for absorbed dose calculation and VSV generation in this study. The Y-90 beta spectrum from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory database was used [32]. The physics list emstandard_opt3 was applied in the simulation, including photoelectric effect, Compton scattering, Rayleigh scattering, multiple scattering and pair production modeled for photons, while positron annihilation, ionization and bremsstrahlung effect were modeled for β particles. Cutting energy of 2 keV was set for all particles to reduce the simulation time.

For absorbed dose calculations, CT images from SPECT/CT and PET/CT were input to GATE to simulate voxelized phantoms. A piecewise linear relationship between Hounsfield unit (HU) and density was obtained from a density phantom calibration [33]. A range translator file based on this relationship was input to GATE to convert HU to different materials, which are defined by densities and elemental compositions [19], [34]. In this study, air (ρ = 0.00126 g/cm3), lungs (ρ = 0.26 g/cm3), soft tissue (ρ = 1.04 g/cm3), liver (ρ = 1.06 g/cm3) and bone (ρ = 1.40 g/cm3) densities defined in ICRP [35] and ICRU [36] were used for linear interpolations to generate new material compositions. The compositions of selected mixture materials are listed in Table S1. ECT images were input as the voxelized source [37] and the DoseActor was attached to CT images to record the dose information in each voxel.

VSVs with SPECT and PET voxel size, i.e., 4.80 × 4.80 × 4.80 mm3 for SPECT, and 4.07 × 4.07 × 3.00 mm3 for PET in this study, and a matrix size of 21 × 21 × 21 were generated, respectively. A total of 1e8 primaries were set for all VSV simulations to ensure uncertainties <2%. The VSV generated in soft tissue was validated with a published dataset [38] (Fig. 2A). Sample VSV kernels generated in liver and lungs are shown in Fig. 2B and provided in the supplementary data [39].

Figure 2.

Sample VSVs used in this study. (A) Validation of the soft tissue VSV generated by GATE v9.0 with N Lanconelli’s result [38]. (B) Profiles of VSVs generated in liver and lung media for Y-90.

2.3. VSV methods

VSV kernels were generated in lung medium (), liver medium (), and 120 media with different densities ranging from 0.01 to 1.40 g/cm3. VSV kernels with density correction [17] and center voxel scaling [21] are defined as and , respectively:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where X=liver or lung, , , indicates the density of voxel (i, j, k), and means the voxel density corresponding to the voxel where the VSV center is located during the convolution.

Ten evaluated VSV methods for Y-90 RE are listed below. The last three methods are newly proposed.

Liver kernel (LiK) [15]:

| (3) |

Liver kernel with density correction (LiKD) [17]:

| (4) |

Liver kernel with center voxel scaling (LiCK) [21]:

| (5) |

Liver kernel and lung kernel (LiLuK) [19]:

| (6) |

Various kernels depending on the center voxel density (VCK) [21]:

| (7) |

The choice of kernels, i.e., KVCK, depends on the density of the voxel where the center voxel of the kernel is located for convolution.

LED:

| (8) |

where =49.67 J/GBq, is the total energy delivered by β- particles from Y-90, V is the voxel size.

Liver and lung kernel with density correction (LiLuKD) [40]:

| (9) |

Liver and lung kernel with center voxel density correction (LiLuCK):

| (10) |

Liver kernel with density correction and lung kernel with center voxel scaling (LiKDLuCK):

| (11) |

Liver kernel with center voxel scaling and lung kernel with density correction (LiCKLuKD):

| (12) |

where D is the total 3D absorbed dose map, is the convolution operator, and represents TIA maps for different VOIs. TIA maps for lungs () and liver () were mapped out from based on the registered binary lungs and liver maps from CT. The absorbed dose maps of lungs (Dlungs), liver (Dliver), tumor (Dtumor), upper liver (DUL) and lower lungs (DLL) were obtained based on the VOI segmentations on the total 3D absorbed dose map D.

2.4. Data analysis

The impact of the interface region to the respective organ absorbed dose was first measured by the percentages of DUL/Dliver and DLL/Dlungs, where D here was obtained based on the MC method.

Absolute absorbed dose error (%AADE) in Dlungs, Dliver, Dtumor, DUL and DLL was analyzed:

| (13) |

where or is the absorbed dose calculated by VSV or MC for voxel n, N is the total number of voxels within the VOI.

Relative difference maps between VSV and MC absorbed dose results were computed to compare the absorbed dose estimation accuracy at the voxel level.

Profiles that passed through the upper liver and lower lungs region were also illustrated for different VSV methods as compared to the MC result for a sample patient.

The cumulative dose volume histograms (CDVH) based on the Y-90 SPECT data were also shown to demonstrate the accuracy of various VSVs.

To compare the computation speed, all methods were run in the single thread mode with a Xeon 6248 CPU and 128 GB RAM.

3. Results

Table 1 lists the median absorbed dose percentage for the interface region, which is ∼6% for liver and >16% for lungs based on MC calculation. For some patients, the percentage for both regions can reach >50% in PET/CT.

Table 1.

Absorbed dose percentages of the interface regions to the respective organ absorbed dose based on MC calculation.

| Median [min, max] |

Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT | Y-90 SPECT/CT | Y-90 PET/CT |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUL/Dliver | 5.9% [3.0%, 21.2%] |

6.8% [0.8%, 46.0%] |

5.5% [0.2%, 52.6%] |

| DLL/Dlungs | 30% [14.7%, 32.0%] |

16.7% [6.1%, 24.8%] |

42.5% [8.5%, 60.8%] |

The %AADE results of all VOIs are shown in Fig. 3 and the results of three types of imaging data are listed in Tables S2, S3 and S4. The median %AADE of liver and tumor is <3% for all VSV methods. For LiKD, the differences were no greater than 0.14%. VSV methods with lung kernel, and lung kernel with center voxel scaling, i.e., LiLuK, VCK, LiLuCK and LiKDLuCK, have larger deviations in the liver. LED has the worst performance in tumors (1-7%). The median %AADE is mostly <6% in the upper liver except for methods with inferior liver absorbed dose estimation, i.e., LiLuK, VCK, LiLuCK and LiKDLuCK.

Figure 3.

Box-whisker plot (displaying the maximum/minimum at the whiskers, the 75/25 percentiles at the boxes, and the median in the center line) of %AADE of each VSV method in Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, Y-90 SPECT/CT and Y-90 PET/CT patient data for (A) liver, (B) lungs, (C) tumor, (D) upper liver, and (E) lower lungs.

The median %AADE is generally higher for lungs. The LiK has the largest errors (∼70%) for three types of imaging data, while other methods achieve <28% error. The introduction of lung kernel, i.e., LiLuK, VCK, LiLuKD, LiLuCK, LiKDLuCK and LiCKLuKD, further improves the lungs’ absorbed dose estimation with <16% error. LiLuCK achieves the lowest median %AADE of <4%. Similar results can also be seen in lower lungs where both LiKDLuCK and LiCKLuKD achieve median %AADE of <7%.

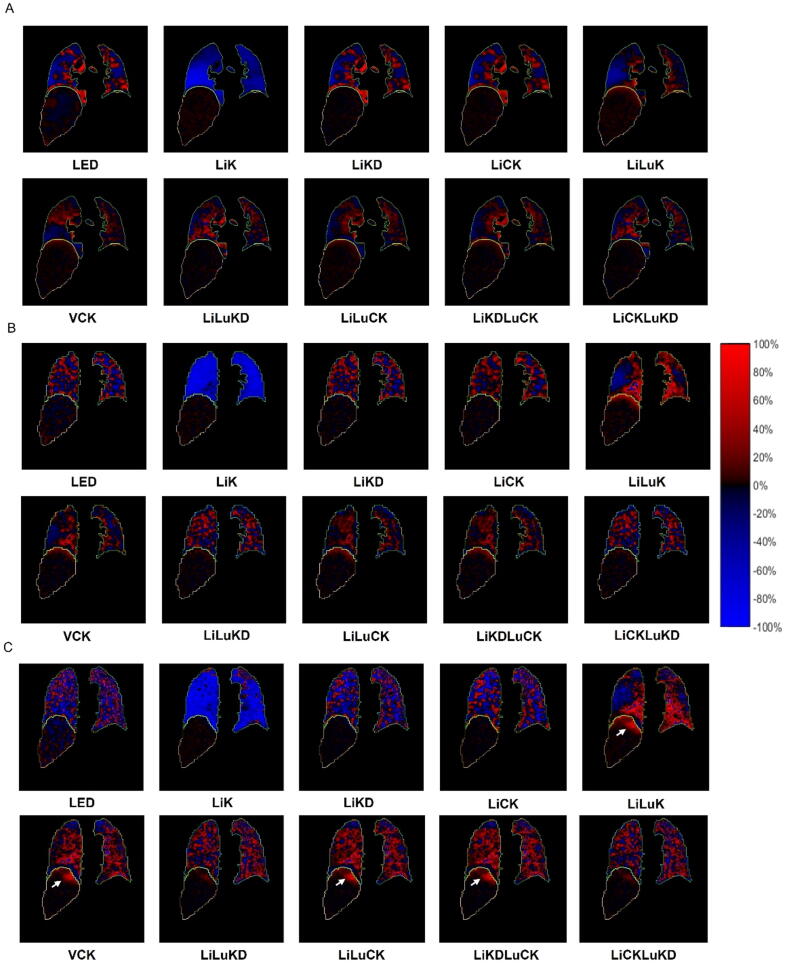

Fig. 4 demonstrates the difference of absorbed dose estimation between MC and various VSV methods for a sample patient. LiK underestimates lung absorbed dose in general, while other methods both underestimate and overestimate absorbed dose in the lungs. The difference is less for the liver in general but started to manifest in the upper liver for LiLuK, VCK, LiLuCK and LiKDLuCK particularly in the PET/CT data, consistent with the %AADE results.

Figure 4.

Absorbed dose difference map of different VSV methods as compared to MC for a sample patient. (A) Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT; (B) Y-90 SPECT/CT; and (C) Y-90 PET/CT. White arrows point out potential overestimation of absorbed dose in the upper liver.

Absorbed dose profiles of each VSV method are shown in Fig. 5. Consistent with the previous results, VSV methods generally perform better in the liver than in the lungs, while applying correction methods to lung kernel, e.g., LiLuKD, LiLuCK, LiCKLuKD and LiKDLuCK, could enhance the matching of profiles in the lungs. Our three proposed methods match well with the MC results as compared to other VSV methods.

Figure 5.

Absorbed dose profiles of each VSV method on the selected liver-lungs boundary region (vertical blue line) in (A) Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, (B) Y-90 SPECT/CT and (C) Y-90 PET/CT patient data. The profile from the MC result is shown as reference.

Fig. 6 shows the CDVHs of Y-90 SPECT for a sample patient. No substantial difference was observed in the liver between the VSV and MC results. LED deviates more in the tumor CDVH as compared with others. LiK underestimates CDVH in the lungs while other VSVs have improved performance, consistent with previous quantitative results.

Figure 6.

CDVHs of Y-90 SPECT/CT data for a sample patient based on various absorbed dose conversion methods: (A) liver, (B) tumor and (C) lungs.

The processing time of all VSV methods takes <30 s for one patient as shown in Table 2, while MC costs ∼200 hours.

Table 2.

Computation time of various absorbed dose conversion method on a sample patient.

| Time (s) | LED | LiK | LiKD | LiCK | LiLuK | VCK | LiLuKD | LiLuCK | LiKDLuCK | LiCKLuKD | MC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT | 0.03 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 18.2 | 4.2 | 15.6 | 5.7 | 19.3 | 27.6 | 24.8 | ∼720000 (200 hrs) |

| Y-90 SPECT/CT | 0.02 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 20.2 | 3.4 | 17.5 | 5.1 | 21.5 | 28.9 | 22.2 | |

| Y-90 PET/CT | 0.03 | 3.2 | 15.2 | 18.2 | 3.5 | 15.6 | 20.7 | 25.1 | 29.4 | 27.3 |

4. Discussion

For some existing VSV methods investigated in this study, e.g. LiLuK, VCK, LiCK, only results of Lu-177 and Ga-68 patient data are reported in literature [19], [21]. According to these studies, advanced VSV method, e.g., VCK, performs better than a single type of VSV method, e.g., LiK, with deviations of 0.5% compared with 52.9% for Ga-68 and 32.4% compared with 47.8% for Lu-177 in estimating the absorbed dose from the lungs compared with MC. In this study, errors are 3.8% vs 68.3%, 2.5% vs 69.4% and 6.5% vs 69.3% for Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, Y-90 SPECT/CT and Y-90 PET/CT, respectively. Our LiK, LED and LiKD absorbed dose estimation results in the liver, tumors and lungs are similar to those reported by Mikell et al [14]. Our results show that LED has more deviation in tumor absorbed dose estimation and CDVH, consistent with results from Morán et al [9].

The liver and tumor absorbed dose are of great concern in Y-90 RE for treatment planning [8] and efficacy analysis [41]. All VSV methods show good agreement with with MC in the liver and tumors when using liver kernel convolved with activity in soft-tissue-like medium, even without any correction. This result is expected since the density of different soft tissues is about 1 g/cm3 with a small deviation [42]. Although LiLuK, VCK, LiLuCK and LiKDLuCK methods may have higher deviations in the liver absorbed dose estimation, all VSV methods provide consistent CDVH curves with MC in the liver and tumors (Fig. 6). For Y-90 PET/CT, LiK, LiKD, LiCK, LiLuKD and LiCKLuKD have the better performance with maximum %AADE of 2.02%, 1.31%, 1.53%, 1.56% and 2.20% in the liver and tumors.

For Y-90 RE, lung absorbed dose estimation in pre- and post-treatment is important, particularly for patients with a higher lung shunt fraction as it is linked to radiation pneumonitis, which is a potentially fatal side effect [43]. However, activity distributed in lungs is generally sparse and density changes greatly from 0.00126 g/cm3 (air) to 1.04 g/cm3 (soft tissue) even within the same organ [44]. Considering Y-90 has a 44 mm range of beta radiation in lung tissues, LED, LiK or LiKD [14], which assume local absorption or a shorter beta range for liver tissues, have inferior performance, with median %AADE from 14% to ∼70%. Whereas VSV methods with the use of lung kernel, e.g., LiLuK, have relatively better absorbed dose estimation for the lungs which can be further improved by density-based corrections, i.e., LiLuCK, LiKDLuCK and LiCKLuKD. For Y-90 PET/CT, the performance improves from median %AADE of 15.04% (LiLuK) to 3.28% (LiLuCK), 6.38% (LiKDLuCK) and 5.05% (LiCKLuKD) in the lungs, respectively.

Table 1 shows that the absorbed doses calculated by MC in the upper liver and the lower lungs account for a large proportion of the total liver (∼6%) and lung (>16%) absorbed dose, respectively. Thus, upper liver and lower lungs are segmented separately to analyze the VSV performance. The use of lung kernel could improve absorbed dose estimation in the lungs and lower lungs, but overestimates absorbed dose in the upper liver if used without effective correction. For Y-90 PET/CT, LiCK, LiLuKD and LiCKLuKD have superior performance in the upper liver with median %AADE of 1.38%, 0.71% and 0.64%, respectively. LiLuK, LiKDLuCK and LiCKLuKD have the lower median %AADE of 10.35%, 4.03% and 6.74% in the lower lungs. Density correction is more effective than center voxel scaling in this case (Figure 4, Figure 6). On the other hand, the absorbed dose contribution from upper liver to lungs cannot be ignored, especially when tumors with high activity are located in that region. In this situation, center voxel scaling is better than density correction. Thus, the combination of LiCK and LuKD, i.e., LiCKLuKD, is generally most comparable with MC in all regions.

Though LED is generally recommended for Y-90 microspheres SPECT absorbed dose estimation due to the relatively inferior resolution of SPECT [45], VSV-based absorbed dose estimation remains an efficient and precise gateway for clinical pre- and post-therapy Y-90 RE dosimetric implementation, especially considering better achievable spatial resolution of ECT images available from advanced imaging equipment and quantitation capability. Moreover, conventional 2D dosimetry methods do not consider heterogeneous absorbed dose distribution, which may be correlated with tumor dose response and complications as suggested by external beam radiotherapy [46], [47]. Voxel-based pre- and post-therapy dosimetry models for Y-90 RE warrant more investigations.

In our study, the matrix size is set to 21 × 21 × 21 for all types of VSVs to include 99% deposited energy from β- particles emitted from center voxel. Further optimization of the matrix sizes for different kernel types is feasible to enhance the computational time and accuracy. In addition, some absorbed dose calculation methods for Y-90 RE are not assessed in this study. The percentage scaling method proposed by Moghadam et al [18] is not implemented due to its long computation time [21]. Collapsed cone superposition method [48] is also not implemented, as its accuracy depends on the number of spherical cones and is computationally intensive. Evaluations based on more patient data are warranted.

5. Conclusions

We proposed three new VSV methods and evaluated them along with seven existing VSV methods for dosimetric analysis on Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT, Y-90 microspheres SPECT/CT and PET/CT patient data. All VSV methods had relatively small errors in liver and tumor absorbed dose estimation with median %AADE <3%. Methods with tissue-specific kernel and effective density correction, i.e., LiLuKD and LiCKLuKD, achieved lower errors in the lungs absorbed dose estimation without compromising upper liver absorbed dose estimation. Personalized VSV methods provide fast and precise absorbed dose estimation for pre-therapy treatment planning and post-therapy analysis in clinical Y-90 RE practice.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was performed in part at SICC which is supported by SKL-IOTSC, UNIV. OF MACAU.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundo para o Desenvolvimento das Ciências e da Tecnologia (FDCT 0091/2019/A2 & 0099/2021/A); and Open Program of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (HXY21008).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zemedi.2022.11.003.

Contributor Information

Yue Chen, Email: chenyue5523@126.com.

Greta S.P. Mok, Email: gretamok@um.edu.mo.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Salem R., Gabr A., Riaz A., Mora R., Ali R., Abecassis M., et al. Institutional decision to adopt Y90 as primary treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma informed by a 1,000-patient 15-year experience. Hepatology. 2018;68:1429–1440. doi: 10.1002/hep.29691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elsayed M., Cheng B., Xing M., Sethi I., Brandon D., Schuster D.M., et al. Comparison of Tc-99m MAA planar versus SPECT/CT imaging for lung shunt fraction evaluation prior to Y-90 radioembolization: are we overestimating lung shunt fraction? CardioVasc Intervent Radiol. 2021;44:254–260. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02638-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho S., Lau W.Y., Leung T.W., Chan M., Johnson P.J., Li A.K. Clinical evaluation of the partition model for estimating radiation doses from yttrium-90 microspheres in the treatment of hepatic cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 1997;24:293–298. doi: 10.1007/BF01728766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosser O.S., Ulrich G., Furth C., Pech M., Ricke J., Amthauer H., et al. Intrahepatic activity distribution in radioembolization with yttrium-90–labeled resin microspheres using the body surface area method—a less than perfect model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikell J.K., Mahvash A., Siman W., Baladandayuthapani V., Mourtada F., Kappadath S.C. Selective internal radiation therapy with yttrium-90 glass microspheres: biases and uncertainties in absorbed dose calculations between clinical dosimetry models. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2016;96:888–896. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tafti B.A., Padia S.A. Dosimetry of Y-90 microspheres utilizing Tc-99m SPECT and Y-90 PET. Seminars Nucl Med: Elsevier. 2019:211–217. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T.T., Ao E.C.I., Lambert B., Brans B., Vandenberghe S., Mok G.S.P. Quantitative imaging for targeted radionuclide therapy dosimetry - technical review. Theranostics. 2017;7:4551–4565. doi: 10.7150/thno.19782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieudonné A., Garin E., Laffont S., Rolland Y., Lebtahi R., Leguludec D., et al. Clinical feasibility of fast 3-dimensional dosimetry of the liver for treatment planning of hepatocellular carcinoma with 90Y-microspheres. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1930–1937. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morán V., Prieto E., Sancho L., Rodríguez-Fraile M., Soria L., Zubiria A., et al. Impact of the dosimetry approach on the resulting 90Y radioembolization planned absorbed doses based on 99mTc-MAA SPECT-CT: is there agreement between dosimetry methods? EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s40658-020-00343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giammarile F., Bodei L., Chiesa C., Flux G., Forrer F., Kraeber-Bodere F., et al. EANM procedure guideline for the treatment of liver cancer and liver metastases with intra-arterial radioactive compounds. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1393–1406. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiesa C., Sjogreen-Gleisner K., Walrand S., Strigari L., Flux G., Gear J., et al. EANM dosimetry committee series on standard operational procedures: a unified methodology for 99mTc-MAA pre-and 90Y peri-therapy dosimetry in liver radioembolization with 90Y microspheres. EJNMMI Phys. 2021;8:1–44. doi: 10.1186/s40658-021-00394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y.C., Kim Y.H., Uhm S.H., Seo Y.S., Park E.K., Oh S.Y., et al. Radiation safety issues in y-90 microsphere selective hepatic radioembolization therapy: possible radiation exposure from the patients. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;44:252–260. doi: 10.1007/s13139-010-0047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mok G.S., Dewaraja Y.K. Recent advances in voxel-based targeted radionuclide therapy dosimetry. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021;11:483. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikell J.K., Mahvash A., Siman W., Mourtada F., Kappadath S.C. Comparing voxel-based absorbed dosimetry methods in tumors, liver, lung, and at the liver-lung interface for 90 Y microsphere selective internal radiation therapy. EJNMMI Phys. 2015;2:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40658-015-0119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolch W.E., Bouchet L.G., Robertson J.S., Wessels B.W., Siegel J.A., Howell R.W., et al. MIRD pamphlet no. 17: the dosimetry of nonuniform activity distributions—radionuclide S values at the voxel level. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:11S–36S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes J., Celler A. Comparison of internal dose estimates obtained using organ-level, voxel S value, and Monte Carlo techniques. Med Phys. 2014;41:092501. doi: 10.1118/1.4892606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieudonné A., Hobbs R.F., Lebtahi R., Maurel F., Baechler S., Wahl R.L., et al. Study of the impact of tissue density heterogeneities on 3-dimensional abdominal dosimetry: comparison between dose kernel convolution and direct Monte Carlo methods. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:236–243. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khazaee Moghadam M., Kamali Asl A., Geramifar P., Zaidi H. Evaluating the application of tissue-specific dose kernels instead of water dose kernels in internal dosimetry: a Monte Carlo study. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2016;31:367–379. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2016.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee M.S., Kim J.H., Paeng J.C., Kang K.W., Jeong J.M., Lee D.S., et al. Whole-body voxel-based personalized dosimetry: the multiple voxel S-value approach for heterogeneous media with nonuniform activity distributions. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1133–1139. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.201095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacilio M., Amato E., Lanconelli N., Basile C., Torres L.A., Botta F., et al. Differences in 3D dose distributions due to calculation method of voxel S-values and the influence of image blurring in SPECT. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:1945. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/5/1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Götz T., Schmidkonz C., Lang E., Maier A., Kuwert T., Ritt P. A comparison of methods for adapting dose-voxel-kernels to tissue inhomogeneities. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64:245011. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab5b81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strigari L., Sciuto R., Rea S., Carpanese L., Pizzi G., Soriani A., et al. Efficacy and toxicity related to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with 90Y-SIR spheres: radiobiologic considerations. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1377–1385. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.075861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangro B., Martínez-Urbistondo D., Bester L., Bilbao J.I., Coldwell D.M., Flamen P., et al. Prevention and treatment of complications of selective internal radiation therapy: expert guidance and systematic review. Hepatology. 2017;66:969–982. doi: 10.1002/hep.29207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhavanallaf A., Shiri I., Arabi H., Zaidi H. Whole-body voxel-based internal dosimetry using deep learning. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:670–682. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Götz T.I., Lang E.W., Schmidkonz C., Kuwert T., Ludwig B. Dose voxel kernel prediction with neural networks for radiation dose estimation. Z Med Phys. 2021;31:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.zemedi.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van B, Dewaraja, Y. Y-90 PET/CT & SPECT/CT and Corresponding Contours Dataset 31JULY2020. University of Michigan - Deep Blue ed; 2020.

- 27.Lim H, Dewaraja, Y. Y-90 patients PET/CT & SPECT/CT and corresponding contours dataset. University of Michigan - Deep Blue ed; 2019.

- 28.Dewaraja Y.K., Chun S.Y., Srinivasa R.N., Kaza R.K., Cuneo K.C., Majdalany B.S., et al. Improved quantitative 90Y bremsstrahlung SPECT/CT reconstruction with Monte Carlo scatter modeling. Med Phys. 2017;44:6364–6376. doi: 10.1002/mp.12597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van B.J., Dewaraja Y.K., Sangogo M.L., Mikell J.K. Y-90 SIRT: evaluation of TCP variation across dosimetric models. EJNMMI Phys. 2021;8:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40658-021-00391-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yushkevich P.A., Piven J., Hazlett H.C., Smith R.G., Ho S., Gee J.C., et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu Z., Chen G., Lin K.H., Wu T.H., Mok G.S. Evaluation of different CT maps for attenuation correction and segmentation in static 99mTc-MAA SPECT/CT for 90Y radioembolization treatment planning: A simulation study. Med Phys. 2021;48:3842–3851. doi: 10.1002/mp.14991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu LPE SYF, Firestone RB. Table of Radioactive Isotopes, database version 2/28/99; 2012.

- 33.Rong Y., Smilowitz J., Tewatia D., Tome W.A., Paliwal B. Dose calculation on kV cone beam CT images: an investigation of the Hu-density conversion stability and dose accuracy using the site-specific calibration. Med Dosim. 2010;35:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.meddos.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider W., Bortfeld T., Schlegel W. Correlation between CT numbers and tissue parameters needed for Monte Carlo simulations of clinical dose distributions. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:459. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/2/314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Killough G., Rohwer P. Oak Ridge National Lab.; 1974. INDOS: conversational computer codes to implement ICRP-10-10A models for estimation of internal radiation dose to man. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffiths H.J. Tissue substitutes in radiation dosimetry and measurement. No. 4. Radiology. 1989;173:202-. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jan S., Benoit D., Becheva E., Carlier T., Cassol F., Descourt P., et al. GATE V6: a major enhancement of the GATE simulation platform enabling modelling of CT and radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:881. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/4/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanconelli N., Pacilio M., Meo S.L., Botta F., Di Dia A., Aroche L.T., et al. A free database of radionuclide voxel S values for the dosimetry of nonuniform activity distributions. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:517. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/2/517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li T., Zhu L., Lu Z., Song N., Lin K.-H., Mok G.S. BIGDOSE: software for 3D personalized targeted radionuclide therapy dosimetry. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10:160. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.10.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brosch-Lenz J., Uribe C., Gosewisch A., Kaiser L., Todica A., Ilhan H., et al. Influence of dosimetry method on bone lesion absorbed dose estimates in PSMA therapy: application to mCRPC patients receiving Lu-177-PSMA-I&T. EJNMMI Phys. 2021;8:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40658-021-00369-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kappadath S.C., Mikell J., Balagopal A., Baladandayuthapani V., Kaseb A., Mahvash A. Hepatocellular carcinoma tumor dose response after 90Y-radioembolization with glass microspheres using 90Y-SPECT/CT-based voxel dosimetry. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khazaee M., Asl A.K., Geramifar P. SU-E-T-154: calculation of tissue dose point kernels using GATE Monte Carlo simulation toolkit to compare with water dose point kernel. Med Phys. 2015;42:3367-. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sangro B., Martinez-Urbistondo D., Bester L., Bilbao J.I., Coldwell D.M., Flamen P., et al. Prevention and treatment of complications of selective internal radiation therapy: Expert guidance and systematic review. Hepatology. 2017;66:969–982. doi: 10.1002/hep.29207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fromson B., Denison D. Quantitative features in the computed tomography of healthy lungs. Thorax. 1988;43:120–126. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasciak A.S., Erwin W.D. Effect of voxel size and computation method on Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT-based dose estimation for Y-90 microsphere therapy. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2009;28:1754–1758. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2022753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang T.-H., Huang P.-I., Hu Y.-W., Lin K.-H., Liu C.-S., Lin Y.-Y., et al. Combined Yttrium-90 microsphere selective internal radiation therapy and external beam radiotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: From clinical aspects to dosimetry. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lasley F.D., Mannina E.M., Johnson C.S., Perkins S.M., Althouse S., Maluccio M., et al. Treatment variables related to liver toxicity in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, Child-Pugh class A and B enrolled in a phase 1–2 trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:e443–e449. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchez-Garcia M., Gardin I., Lebtahi R., Dieudonné A. A new approach for dose calculation in targeted radionuclide therapy (TRT) based on collapsed cone superposition: validation with 90Y. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59:4769. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/17/4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.