Abstract

Objective

The IL-23 p19-subunit inhibitor guselkumab has been previously compared with other targeted therapies for PsA through network meta-analysis (NMA). The objective of this NMA update was to include new guselkumab COSMOS trial data, and two key comparators: the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab and the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib.

Material and methods

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials up to February 2021. A hand-search identified newer agents up to July 2021. Bayesian NMAs were performed to compare treatments on ACR response, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response, modified van der Heijde–Sharp (vdH-S) score, and serious adverse events (SAEs).

Results

For ACR 20, guselkumab 100 mg every 8 weeks (Q8W) and every 4 weeks (Q4W) were comparable (i.e. overlap in credible intervals) to most other agents, including risankizumab, upadacitinib, subcutaneous TNF inhibitors and most IL-17A inhibitors. For PASI 90, guselkumab Q8W and Q4W were better than multiple agents, including subcutaneous TNF and JAK inhibitors. For vdH-S, guselkumab Q8W was similar to risankizumab, while guselkumab Q4W was better; both doses were comparable to most other agents. Most agents had comparable SAEs.

Conclusions

Guselkumab demonstrates better skin efficacy than most other targeted PsA therapies, including upadacitinib. For vdH-S, both guselkumab doses are comparable to most treatments, with both doses ranking higher than most, including upadacitinib and risankizumab. Both guselkumab doses demonstrate comparable ACR responses to most other agents, including upadacitinib and risankizumab, and rank favourably in the network for SAEs.

Keywords: Comparative effectiveness research, PsA, systematic literature review, network meta-analysis, guselkumab, ACR response, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response, modified van der Heijde–Sharp (vdH-S) score, serious adverse events

Rheumatology key messages.

Guselkumab offers better skin efficacy than many other targeted therapies for PsA.

Guselkumab offers arthritis efficacy that is comparable to IL-17A, JAK, and subcutaneous TNF inhibitors.

Guselkumab has a favourable safety profile similar to most other agents.

Introduction

PsA is a chronic and progressive inflammatory disease comprising several clinical phenotypes including peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin and nail psoriasis [1]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have approved numerous targeted synthetic (ts) and biologic (b) DMARDs for PsA. Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated treatment efficacy and safety against placebo, the scarcity of head-to-head studies in PsA precludes direct comparisons, which is challenging for clinicians and payers [2–4]. To address this, network meta-analysis (NMA) compares multiple therapies directly and indirectly through a common anchor, such as placebo [5].

The relative efficacy and safety of PsA treatments was examined in our previous systematic literature review (SLR) and NMA [6]. Guselkumab, an IL-23 p19-subunit inhibitor, showed favourable Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI] responses and comparable arthritis efficacy (i.e. ACR and modified van der Heijde–Sharp [vdH-S] scores) relative to IL-17A and most TNFα (TNF) inhibitors, and ranked highly for adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) [6]. Guselkumab data were sourced from phase 3 trials DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 [7, 8]. However, at the time of the NMA, guselkumab data were unavailable from COSMOS, a phase 3b trial in patients with an inadequate response (IR) to TNF inhibitors [9].

Also, at the time the previous NMA was conducted, efficacy and safety data were unavailable from two new comparators for PsA: the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab and the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib. Risankizumab was better than placebo for ACR 20 and PASI 90 in patients with an IR or intolerance to at least one conventional synthetic (cs) DMARD (KEEPsAKE-1), and in patients with an IR or intolerance to at least one bDMARD or csDMARD (KEEPsAKE-2) [10–12]. In SELECT-PsA 1, upadacitinib 15 mg was comparable to adalimumab, and better than placebo, for ACR 20 and PASI 75 in patients with a history of IR to at least one csDMARD [13]. In SELECT-PsA 2, both upadacitinib doses (15 mg and 30 mg) were better than placebo for ACR 20 and PASI 75/90/100 in patients with a history of IR to at least one bDMARD [14]. The relative efficacy of these comparators against other targeted PsA therapies has not been assessed.

The objective of this NMA update was to include guselkumab data in patients with an IR to TNF inhibitors, and to add risankizumab and upadacitinib to the network to compare all targeted therapies in PsA on arthritis and skin efficacy, as well as safety.

Patients and methods

Systematic literature review

The SLR focused on RCTs assessing tsDMARDs and bDMARDs in adults with active PsA. The SLR and NMA protocols were drafted a priori, registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020152614) in April 2020, and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [15] and the corresponding extension statement for NMA [16]. An information specialist conducted electronic searches of databases, including EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, using controlled vocabulary and keywords (Supplementary Data S1, available at Rheumatology online). The search informing Mease et al. 2021 [6] was updated in February 2021. A subsequent hand-search was performed to identify newer agents, including abstracts, up to July 2021. There were no date restrictions on the search strategy or results.

Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment

Relevant studies were identified using pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Citations were screened by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by discussion or involvement of a third reviewer. Data for included studies were extracted into a standardized Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) form by one reviewer and validated by a second. Collected data consisted of publication characteristics, study populations, interventions and comparators studied, outcomes reported, and study design. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical effectiveness quality assessment checklist was used to evaluate study quality [17].

Deviations from PROSPERO protocol

Because the objective was to include the most recent data available for targeted PsA therapies, risankizumab, although not yet EMA or FDA approved, was included as a comparator of interest. Also, phase 3 data for risankizumab were only available from abstracts [10–12]. Thus, relevant abstracts were included, and values were confirmed when publications became available [18, 19].

NMA

Bayesian NMAs were performed to compare treatments on ACR 20/50/70 response, change from baseline in vdH-S score, PASI 75/90/100 response and SAEs [20–22]. The evidence base for each outcome of interest was visualized using network diagrams; each unique treatment dose is shown as a node and trials as lines connecting these nodes. ACR and PASI data were from the primary assessment time point of each study, which varied from 12 to 24 weeks. For vdH-S, data were at 24 weeks, the only time point feasible for analyses during the placebo-controlled period. For SAEs, the latest placebo-controlled time point was used up to 24 weeks. In the COSMOS trial, patients with <5% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts at week 16 qualified for early escape (EE). Guselkumab-treated patients continued randomized treatment (receiving placebo at week 16 to maintain blinding), while the placebo-treated patients received guselkumab at weeks 16, 20 and every 8 weeks thereafter. Eight participants receiving placebo and 12 receiving guselkumab were incorrectly routed to EE at week 16 without meeting the necessary criteria. An analysis correcting for the EE error was prospectively added to the trial analysis plan, and these corrected data were used for analysis. The primary analysis data from COSMOS for ACR and PASI were analysed in sensitivity analyses.

A multinomial probit NMA model for ordinal outcomes was used to compare interventions for ACR and PASI, dichotomous outcomes were used for SAEs, and continuous outcomes were used for vdH-S score. Models appropriately accounted for multi-arm trials. Treatment effects for ordinal outcomes were modelled on the probit scale and treatment effects for dichotomous outcomes were modelled on the log-odds ratio scale. Treatment effects from ordinal and dichotomous models were transformed to relative risks (RR) using the unweighted average of trial placebo responses. For continuous outcomes, treatment effects were modelled and reported on the mean difference (MD) scale.

Assessment of model fit was based on criteria outlined in the NICE Decision Support Unit Technical Support Document (DSU TSD) series [20–22]. Random effects models were conducted by default, as the approach to model selection accounted for the clinical heterogeneity previously described in NMAs in PsA and psoriasis (i.e. differences in patient characteristics and study designs) [23–25]. Fixed effect models were considered when evidence networks comprised single or double-study connections. To further account for cross-trial heterogeneity, variation in placebo response across trials was adjusted using meta-regressions on baseline risk where appropriate. A single interaction effect that represents the relative treatment effect comparisons between treatments and placebo was used in all meta-regressions. Variation in placebo response is an important effect modifier in PsA that represents a proxy for variation in measured and unmeasured confounding variables [21]. Models that adjusted for placebo response were based on code reported in the NICE DSU TSD 3 [21].

League tables from best-fitting models (assessed by model fit diagnostics) present pairwise comparisons between treatments in each network in terms of RR and MD and associated 95% credible intervals (CrI). Within the table, each column header treatment is compared with the reference row treatment, with highest-ranked treatments at the top-left. Pairwise results are interpreted conservatively according to overlap of 95% CrIs and address statistical uncertainty. Treatments are comparable if CrIs overlap 1 (dichotomous outcomes) or 0 (continuous outcomes), although point estimates may favour one treatment over another. When pairwise 95% CrI do not overlap with 0 or 1 for their respective outcomes, there is a >95% probability that treatments are different, which is described as ‘better’ or ‘worse’ vs the other treatment, depending on the direction of effect.

Analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and JAGS, based on code reported in the NICE DSU TSD Series [20–22]. Convergence was monitored quantitatively using the latest implementation Gelman–Rubin diagnostic (Rhat) based on four chains (Supplementary Data S2, available at Rheumatology online) [26]. Models were fit using four chains and used vague priors (Supplementary Data S3 and Table S2, available at Rheumatology online). An unrelated mean effects model was used to test for the presence of inconsistency.

Results

Systematic literature review results

The SLR identified 4364 citations. COSMOS data were provided by the manufacturer. Three trials identified by the hand-search were also included: SELECT-PSA 1 (upadacitinib) [13], and KEEPsAKE-1 [10, 12] and KEEPsAKE-2 [11] (risankizumab). The NMA included 33 trials (87 citations) evaluating all doses of tsDMARDS and bDMARDs approved by either the FDA or EMA for treatment of active PsA. The PRISMA diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection for systematic literature review and hand-search. NCT: National Clinical Trial

Study and patient characteristics from the systematic literature review

Studies included inhibitors of the following classes: cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (abatacept), IL-12/23 (ustekinumab), IL-17A (ixekizumab, secukinumab), IL-23 (guselkumab, risankizumab), JAK (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), subcutaneous TNF (adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab), intravenous (i.v.) TNF (golimumab, infliximab) and phosphodiesterase 4 (apremilast). This amounts to 15 targeted PsA therapies, plus placebo, for a total of 23 unique treatment doses. Studies were published between 2004 and 2022; 17 were conducted in biologic-naïve patients, four in biologic-experienced patients and 12 included a mixed population. Across studies, the primary assessment time point varied: week 12 for adalimumab, certolizumab, tofacitinib and upadacitinib; week 14 for golimumab and infliximab; week 16 for apremilast; week 24 for abatacept, etanercept, guselkumab, ixekizumab, risankizumab and ustekinumab; and week 12, 16 or 24 for secukinumab. For each study, baseline characteristics are in Supplementary Table S3 (available at Rheumatology online), and risk of bias assessments are in Supplementary Table S4 (available at Rheumatology online). A high risk of bias was rarely detected in any of the categories, for any included RCT.

NMA results

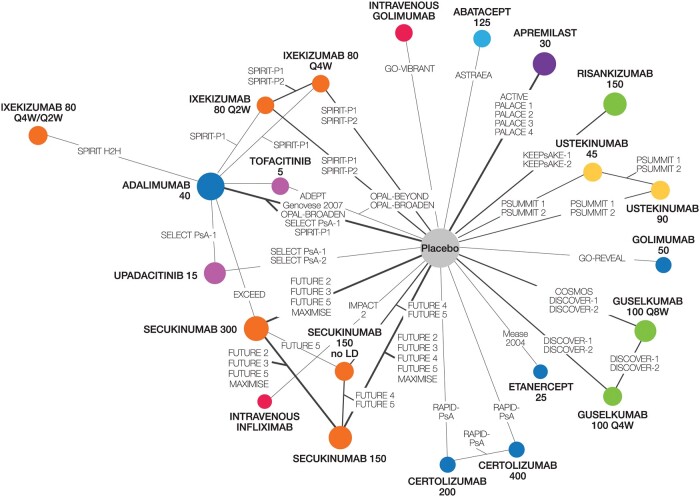

Trials and treatments included in each NMA are presented in Supplementary Table S5, available at Rheumatology online. As the IL-17 receptor A inhibitor brodalumab was not approved for PsA, nor was it undergoing FDA or EMA review at the time of the search (February 2021), it was excluded as a comparator. At the time of drafting this manuscript, upadacitinib 30 mg was not licenced by the EMA and only the 15 mg dose was under review by the FDA; thus, only the 15 mg dose was included in the network. Risankizumab was also under EMA and FDA review but was included in the analysis as it was a comparator of interest. As of April 2022, upadacitinib 30 mg is not a licenced FDA dose, while risankizumab is approved for PsA by both agencies. Thus, the network reflects all treatments and doses approved by the FDA or EMA. No inconsistency was observed across networks (Supplementary Tables S6–S8 and Figs S1–S3, available at Rheumatology online). Of the 33 trials included, ACR was reported in 33 (Fig. 2), vdH-S scores in 11 (Supplementary Fig. S4, available at Rheumatology online), PASI in 30 (Supplementary Fig. S5, available at Rheumatology online) and SAEs in 31 (Supplementary Fig. S6, available at Rheumatology online).

Figure 2.

Evidence network for multi-ACR. The network includes all treatments and doses that are approved by either the FDA or EMA. Treatment nodes are sized to reflect the proportionate number of patients randomized to each treatment in the network. Thickness of lines between nodes corresponds to the number of RCTs connecting treatments. Colours show inhibitor class: light blue: cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; yellow: interleukin-12/23; orange: interleukin-17A; green: interleukin-23; pink: Janus kinase; purple: phosphodiesterase-4; red: intravenous TNF; dark blue: subcutaneous TNF. EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; LD: loading dose; Q2W: every 2 weeks; Q4W: every 4 weeks; Q8W: every 8 weeks; RCT: randomized controlled trial

League tables are presented in the main text for ACR 20, PASI 90, vdH-S and SAEs, with other ACR and PASI thresholds included as Supplementary Figs S7–S10 (available at Rheumatology online). A baseline risk-adjusted, random effects model provided better model fits for ACR, PASI and SAEs; an unadjusted, fixed effect model was preferable for vdH-S scores (Supplementary Table S9, available at Rheumatology online). Forest plots for each outcome are presented as Supplementary Figs S11–S18, available at Rheumatology online. Absolute probabilities/scores for each outcome are presented as Supplementary Tables S10–S13, available at Rheumatology online.

Arthritis efficacy

ACR response

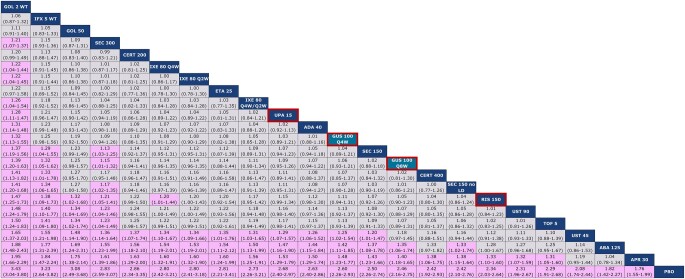

The network diagram for multi-ACR is shown in Fig. 2. All studies reported ACR 20, all but one reported ACR 50 and all but three reported ACR 70. For ACR 20, guselkumab every 8 weeks (Q8W) and every 4 weeks (Q4W) ranked 14th and 12th, respectively, among 23 interventions and were comparable to most other active agents, including risankizumab, JAK inhibitors, subcutaneous TNFs, ustekinumab 90 mg and most IL-17A inhibitors, as demonstrated by overlap in 95% CrIs (Fig. 3). Notably, guselkumab Q8W had a better ACR 20 response than abatacept and apremilast, while guselkumab Q4W also had a better response against these agents, and ustekinumab 45 mg, as demonstrated by non-overlap in 95% CrIs. Intravenous TNFs and secukinumab 300 mg had a better ACR 20 response than guselkumab Q8W, while only i.v. golimumab had a better ACR 20 response than guselkumab Q4W. Given the use of a multinomial model, all conclusions for guselkumab remained the same for ACR 50 and 70 (Supplementary Figs S7 and S8, available at Rheumatology online).

Figure 3.

Baseline risk-adjusted random effects league table for multi-ACR 20 response. Interventions are ordered from top-left to bottom-right in order of decreasing mean rank. For each pairwise comparison, the row treatment serves as the reference group. Pairwise comparisons from the baseline-risk adjusted, random effects NMA model are shown in terms of RRs and 95% CrIs. A RR >1 favours the treatment in a given column. RRs with CrIs that do not span unity are shown with a purple background. Both guselkumab doses are shaded in teal and outlined in red, while risankizumab and upadacitinib are outlined in red. ABA: abatacept; ADA: adalimumab; APR: apremilast; CERT: certolizumab; Crl: credible interval; ETA: etanercept; GOL: golimumab; GUS: guselkumab; IFX: infliximab; IXE: ixekizumab; LD: loading dose; NMA: network meta-analysis; PBO: placebo; Q2W: every 2 weeks; Q4W: every 4 weeks; Q8W: every 8 weeks; RIS: risankizumab; RR: relative risk; SEC: secukinumab; TOF: tofacitinib; UPA: upadacitinib; UST: ustekinumab; WT: weight-based (i.e. intravenous)

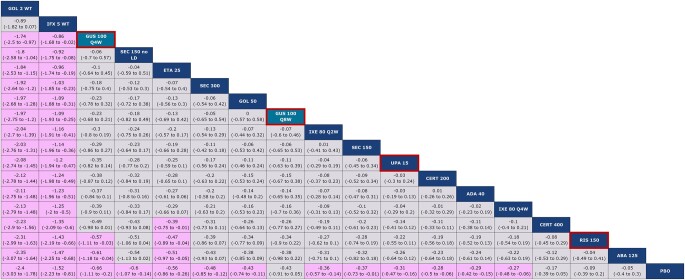

vdH-S score

The network diagram for vdH-S score is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, available at Rheumatology online. Guselkumab Q8W and Q4W ranked eighth and third, respectively, among 18 interventions (Fig. 4). Notably, guselkumab Q4W was better than risankizumab and abatacept, as demonstrated by non-overlap in 95% Crls. Both guselkumab doses were comparable to most other agents, including upadacitinib, but worse than i.v. TNF therapies (i.e. golimumab and infliximab).

Figure 4.

Unadjusted fixed effect league table for vdH-S score. Interventions are ordered from top-left to bottom-right in order of decreasing mean rank. For each pairwise comparison, the row treatment serves as the reference group. Pairwise comparisons from the unadjusted, fixed effect NMA model are shown in terms of MDs and 95% CrIs. A MD <0 favours the treatment in a given column. MDs with CrIs that do not span zero are shown with a purple background. Both guselkumab doses are shaded in teal and outlined in red, while risankizumab and upadacitinib are outlined in red. ABA: abatacept; ADA: adalimumab; CERT: certolizumab; Crl: credible interval; ETA: etanercept; GOL: golimumab; GUS: guselkumab; IFX: infliximab; IXE: ixekizumab; LD: loading dose; MD: mean difference; NMA: network meta-analysis; PBO: placebo; Q2W: every 2 weeks; Q4W: every 4 weeks; Q8W: every 8 weeks; RIS: risankizumab; SEC: secukinumab; UPA: upadacitinib; vdH-S: van der Heijde–Sharp; WT: weight-based (i.e. intravenous)

Skin efficacy

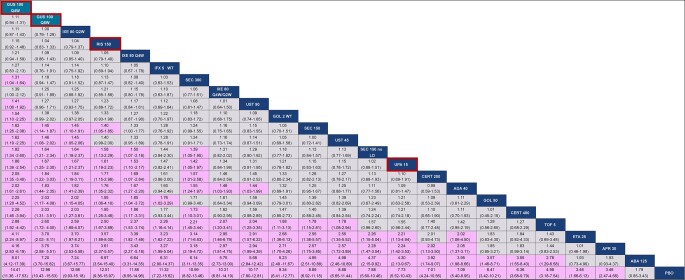

The network diagram for multi-PASI is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5, available at Rheumatology online. Thirty studies reported PASI data: 27 reported PASI 75, 23 reported PASI 90, and 11 reported PASI 100. For PASI 90, guselkumab Q8W and Q4W ranked second and first, respectively, among 23 interventions and were better than most agents, including all subcutaneous TNF and JAK inhibitors, ustekinumab 45 mg, apremilast and abatacept, as demonstrated by non-overlap in 95% Crls (Fig. 5). Both guselkumab doses were comparable to risankizumab and most IL-17A inhibitors for PASI 90, but point estimates consistently favoured guselkumab. Given the use of a multinomial model, all conclusions for guselkumab remained the same for PASI 75 and 100 (Supplementary Figs S9 and S10, available at Rheumatology online).

Figure 5.

Baseline risk-adjusted random effects league table for multi-PASI 90 response. Interventions are ordered from top-left to bottom-right in order of decreasing mean rank. For each pairwise comparison, the row treatment serves as the reference group. Pairwise comparisons from the baseline risk-adjusted, random effects NMA model are shown in terms of RRs and 95% CrIs. A RR >1 favours the treatment in a given column. RRs with CrIs that do not span unity are shown with a purple background. Both guselkumab doses are shaded in teal and outlined in red, while risankizumab and upadacitinib are outlined in red. ABA: abatacept; ADA: adalimumab; APR: apremilast; CERT: certolizumab; Crl: credible interval; ETA: etanercept; GOL: golimumab; GUS: guselkumab; IFX: infliximab; IXE: ixekizumab; LD: loading dose; NMA: network meta-analysis; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBO: placebo; Q2W: every 2 weeks; Q4W: every 4 weeks; Q8W: every 8 eight weeks; RIS: risankizumab; RR: relative risk; SEC: secukinumab; TOF: tofacitinib; UPA: upadacitinib; UST: ustekinumab; WT: weight-based (i.e. intravenous)

SAEs

The network diagram for SAEs is shown in Supplementary Fig. S6, available at Rheumatology online. Most agents were comparable for SAEs. Guselkumab Q8W and Q4W ranked ninth and sixth, respectively, among 23 interventions (Fig. 6). Both guselkumab doses were better than certolizumab 400 mg and infliximab 5 mg. Risankizumab and upadacitinib were similar to all other agents in the network.

Figure 6.

Baseline risk-adjusted random effects league table for SAEs. Interventions are ordered from top-left to bottom-right in order of decreasing mean rank. For each pairwise comparison, the row treatment serves as the reference group. Pairwise comparisons from the baseline-risk adjusted, random effects NMA model are shown in terms of RRs and 95% CrIs. A RR <1 favours the treatment in a given column. RRs with CrIs that do not span unity are shown with a purple background. Both guselkumab doses are shaded in teal and outlined in red, while risankizumab and upadacitinib are outlined in red. ABA: abatacept; ADA: adalimumab; APR: apremilast; CERT: certolizumab; Crl: credible interval; ETA: etanercept; GOL: golimumab; GUS: guselkumab; IFX: infliximab; IXE: ixekizumab; LD: loading dose; NMA: network meta-analysis; PBO: placebo; Q2W: every 2 weeks; Q4W: every 4 weeks; Q8W: every 8 weeks; RIS: risankizumab; RR: relative risk; SAEs: serious adverse events; SEC: secukinumab; TOF: tofacitinib; UPA: upadacitinib; UST: ustekinumab; WT: weight-based (i.e. intravenous)

Sensitivity analysis (primary analysis data from COSMOS)

Sensitivity analyses using the primary analysis data from COSMOS were generally consistent with analyses using data correcting for the EE error. For ACR 20, guselkumab Q8W and Q4W ranked 16th and 12th, respectively, among 23 interventions and were comparable to most other active agents. Although the rank for guselkumab Q8W decreased by two, all conclusions from the multi-ACR NMA remained unchanged from the main analysis for guselkumab Q8W vs comparators (Supplementary Fig. S19–S21 and Table S14, available at Rheumatology online). For PASI 90, guselkumab Q8W and Q4W ranked third and first, respectively, a decrease of one rank for guselkumab Q8W from the main NMA. All conclusions for guselkumab Q8W vs comparators in the multi-PASI sensitivity analysis remained the same as in the main NMA, except for the comparison vs ustekinumab 45 mg changing from better to comparable, with the CrI at 0.99 (Supplementary Fig. S22–S24 and Table S15, available at Rheumatology online).

Discussion

This study provides an updated analysis of the relative comparative efficacy and safety of available PsA treatments. Notably, this is the first NMA to include the newest DMARDs, risankizumab and upadacitinib. As the number of treatments expands, estimating relative effectiveness and safety through NMA may help guide evidence-based decision making for clinicians and payers [4, 20–22].

Guselkumab provides comparable ACR response vs most targeted PsA treatments, including risankizumab and upadacitinib. Compared with the previous NMA, overall conclusions for ACR 20 in the current analysis were similar, with a few minor changes observed (vs guselkumab Q8W, i.v. infliximab and secukinumab 300 mg changed from comparable to better, ustekinumab 45 mg changed from better to comparable, and no changes were observed for guselkumab Q4W) [6]. For vdH-S score, guselkumab Q8W is comparable to most interventions, consistent with the previous NMA, while guselkumab Q4W is better than risankizumab, but comparable to upadacitinib [6]. The i.v. TNFs golimumab and infliximab offer the highest protection from joint damage according to radiographic progression. For PASI, guselkumab is better than most targeted PsA treatments, including upadacitinib, but comparable to risankizumab. Results were similar to the previous NMA for PASI 90, with a few minor changes (guselkumab Q8W changed from better to comparable vs i.v. golimumab; guselkumab Q4W changed from comparable to better vs secukinumab 300 mg and ustekinumab 90 mg) [6]. Notably, some of the observed changes in the current analysis are likely attributable to switching from binomial models for each ACR and PASI threshold to multinomial models. Lastly, both guselkumab doses ranked highly in the network for SAEs, but significant uncertainty in pairwise estimates was observed, as demonstrated by overlap in 95% CrIs vs most other agents. Compared with the previous NMA, guselkumab Q8W changed from comparable to better than certolizumab 400 mg and infliximab for SAEs [6]. Overall, the results in the current NMA changed slightly but are consistent with the uncertainty expressed in the previous NMA, which lends additional credibility to the method and approach used in both manuscripts.

A Bayesian NMA by Song and Lee demonstrated that both guselkumab doses are comparable to secukinumab 300 mg and 150 mg for ACR 20, based on overlap in 95% CrIs [27]. Song and Lee also suggested that both guselkumab doses had the highest probability of reaching a PASI 75 response compared with both secukinumab doses and placebo [27], based on the surface under the cumulative ranking curve analysis. This is largely consistent with the current study that provides additional information for skin efficacy by using RRs and their 95% CrIs; both guselkumab doses were better than secukinumab 150 mg for PASI response, based on non-overlap of 95% CrIs. Although point estimates favoured guselkumab Q8W over secukinumab 300 mg, only guselkumab Q4W was better than secukinumab 300 mg. In the Song and Lee NMA, both doses of guselkumab and secukinumab were comparable for SAEs, consistent with our findings [27]. Furthermore, a frequentist NMA by Lu et al. found that guselkumab was comparable to most other targeted therapies for PsA for ACR 20, PASI 75 and SAEs [28]. However, this study used only phase 2 data for guselkumab, and did not account for variation in placebo response across trials, which can represent significant heterogeneity [23].

This study has several strengths. First, risankizumab [10–12, 18, 19] and upadacitinib [13, 14] were added to the network, as well as larger sample sizes for secukinumab by adding the MAXIMISE [29] and EXCEED [2] trials. Inclusion of COSMOS provides additional guselkumab data in patients with PsA who had an IR to prior TNF inhibitors, further expanding the evidence base available for analysis. Additional PASI data from the OPAL-BEYOND [30] and OPAL-BROADEN [31] trials and corrected data from FUTURE 5 [32, 33] were also included. Second, the multinomial approach used for ACR and PASI utilizes categorical data more efficiently than a binomial analysis of each category individually [34], which was conducted in the previous NMA [6]. Third, the NMA accounted for variation in placebo response through network meta-regression when model fit statistics suggested that baseline risk-adjusted models provided a better fit to the data. This selection approach aligns with the NICE TSDs [20–22]. All outcomes, except vdH-S, where baseline-risk adjustment was impossible, were best fit by a baseline risk-adjusted model (Supplementary Table S9).

There are some limitations to consider. First, risankizumab and upadacitinib trials were identified by hand-search. However, the value of hand-searching to identify RCTs reported as abstracts was highlighted in a 2007 Cochrane Review [35]. Although risankizumab data were initially available in abstracts, including the full text data resulted in inconsequential changes, supporting the suggestion that abstract results should be included in SLRs if their quality is deemed sufficient [36]. Second, since KEEPsAKE-1 and KEEPsAKE-2 only present PASI 90 data, all categories in the multi-PASI analysis are informed by this one outcome [10–12, 18, 19]. Further, the current study focused on SAEs and analyses in the overall population, as no AE or subgroup data were available from the KEEPsAKE-1 [10, 12] and KEEPsAKE-2 [11] abstracts, respectively. As AE and subgroup data are now available in their respective full texts [18, 19], this presents an opportunity for further analysis. Also, as the assessment time points (12–24 weeks) were limited to the induction period, an NMA analysing data from the maintenance period was impossible due to lack of a placebo anchor. Lastly, while some review teams encourage interpreting effects in terms of clinical significance, we have limited discussion to statistical considerations only, as decisions of clinical significance should be restricted to provider-patient conversations, or via a formal guideline panel including multiple stakeholder perspectives. Readers interested in clinical significance are recommended to apply RR to expected baseline risk using standard approximations [37]. Although claiming strong evidence of superiority based on probability better being >97.5% may risk missing true differences between comparators, this compromise is appropriate given the large number of comparisons increasing the risk of claiming differences which do not exist [38].

In conclusion, guselkumab demonstrates better skin efficacy than most other targeted PsA therapies, including upadacitinib. For vdH-S, both guselkumab doses are comparable to most treatments, with both doses ranking higher than most, including upadacitinib and risankizumab. Both guselkumab doses demonstrate ACR responses that are comparable to most other agents, including upadacitinib and risankizumab, and rank favourably in the network for SAEs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work acknowledges the intellectual contributions made by the broader team at EVERSANA and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, including Alicia Pepper, Cheryl Druchok, Barkha Patel, Tim Disher and Sarah Walsh. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: R.R., S.P., F.H. and A.A. Substantial contributions to the acquisition of the data: R.R., S.P. and A.A. Substantial contributions to the analysis of the data: R.R., S.P. and A.A. Substantial contributions to the interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated: all authors.

Contributor Information

Philip J Mease, Rheumatology Research, Swedish Medical Center/Providence St Joseph Health and University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Iain B McInnes, Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

Lai-Shan Tam, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong and The Prince of Wales Hospital, Sha Tin, New Territories, Hong Kong.

Raji Rajalingam, EVERSANA, Burlington, Ontario, Canada.

Steve Peterson, Janssen Global Services, Horsham, PA, USA.

Fareen Hassan, Janssen EMEA, High Wycombe, UK.

Soumya D Chakravarty, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Horsham, PA, USA; Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Christine Contré, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson and Johnson, Issy-les-Moulneaux, France.

Alison Armstrong, EVERSANA, Burlington, Ontario, Canada.

Wolf-Henning Boehncke, Division of Dermatology and Venereology, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

Christopher Ritchlin, Department of Medicine – Allergy/Immunology and Rheumatology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are sourced from the public domain and are available in the articles cited throughout.

Funding

This work was supported by Janssen Research and Development.

Disclosure statement: P.J.M.: consultancies: AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun, UCB; member of speakers’ bureau: AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; grants/research support: AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun and UCB. I.B.M.: consultancies: AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB. Honoraria: AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; grants/research support: AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB. L.-S.T.: consultancies: Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly; grant/research support from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, GSK, Novartis and Pfizer. R.R. and A.A.: employees of EVERSANA: consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals. S.P.: employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and shareholder of Johnson & Johnson. F.H.: employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and shareholder of Johnson & Johnson. S.D.C.: employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and shareholder of Johnson & Johnson. C.C.: employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and shareholder of Johnson & Johnson. W.-H.B.: support from AbbVie, Almirall, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB. C.R.: consultancies: AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; grants/research support: AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, UCB.

References

- 1. Wervers K, Luime JJ, Tchetverikov I. et al. Influence of disease manifestations on health-related quality of life in early psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2018;45:1526–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McInnes IB, Behrens F, Mease PJ. et al. ; EXCEED Study Group. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis (EXCEED): a double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2020;395:1496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mease PJ, Smolen JS, Behrens F. et al. ; SPIRIT H2H study group. A head-to-head comparison of the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab and adalimumab in biological-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a randomized, open-label, blinded-assessor trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marzo-Ortega H, Packham J, Pujades-Rodriguez M.. ‘Too much of a good thing’: can network meta-analysis guide treatment decision-making in psoriatic arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:3042–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Catalá-López F, Tobías A, Cameron C, Moher D, Hutton B.. Network meta-analysis for comparing treatment effects of multiple interventions: an introduction. Rheumatol Int 2014;34:1489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Tam L-S. et al. Comparative effectiveness of guselkumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:2109–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH. et al. Guselkumab iin patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB. et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V.B. ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of guselkumab in participants with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (Anti-TNF Alpha) therapy (COSMOS) [updated 20 January 2021]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03796858.2019 (7 October 2021, date last accessed).

- 10. Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K. et al. AB0559 Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis after inadequate response or intolerance to DMARDS: 24-week results from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind KEEPsAKE 1 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1315–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ostor A, Van den Bosch F, Papp K. et al. OP0228 Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis, including patients with inadequate response or intolerance to biologic therapies: 24-week results from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, KEEPsAKE 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:138–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K. et al. P25 – Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis after inadequate response or intolerance to DMARDs: 24-week results from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind KEEPsAKE 1 trial. In: 6th World Psoriasis & Psoriatic Arthritis Conference, June 30–July 3, 2021, Stockholm, Sweden. 2021:74–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M. et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Anderson JK. et al. Upadacitinib for psoriatic arthritis refractory to biologics: SELECT-PsA 2. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:312–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM. et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Single technology appraisal: User guide for company evidence submission template [updated 1 April 2017]. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg24/chapter/clinical-effectiveness#quality-assessment-of-the-relevant-clinical-effectiveness-evidence (7 October 2021, date last accessed).

- 18. Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K. et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results from the randomised, double-blind, phase 3 KEEPsAKE 1 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ostor A, Van den Bosch F, Papp K. et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results from the randomised, double-blind, phase 3 KEEPsAKE 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE, Welton NJ.. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making 2013;33:607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ, Ades AE.. Evidence synthesis for decision making 3: heterogeneity—subgroups, meta-regression, bias, and bias-adjustment. Med Decis Making 2013;33:618–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ. et al. Evidence synthesis for decision making 4: inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making 2013;33:641–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cameron C, Druchok C, Hutton B. et al. Guselkumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis during induction phase: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis 2019;4:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nash P, McInnes IB, Mease PJ. et al. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis: comparative effectiveness up to 48 weeks using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther 2018;5:99–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McInnes IB, Nash P, Ritchlin C. et al. Secukinumab for psoriatic arthritis: comparative effectiveness versus licensed biologics/apremilast: a network meta-analysis. J Comp Eff Res 2018;7:1107–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vehtari A, Gelman A, Simpson D, Carpenter B, Bürkner P-C.. Rank-normalization, folding, and localization: an improved R for assessing convergence of MCMC (with discussion). Bayesian Analysis 2021;16:667–718. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song GG, Lee YH.. Relative efficacy and safety of secukinumab and guselkumab for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;59:433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu C, Wallace BI, Waljee AK. et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of targeted DMARDs for active psoriatic arthritis during induction therapy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019;49:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baraliakos X, Gossec L, Pournara E. et al. Secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and axial manifestations: results from the double-blind, randomised, phase 3 MAXIMISE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:582–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF. et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1525–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O. et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mease P, van der Heijde D, Landewé R. et al. Secukinumab improves active psoriatic arthritis symptoms and inhibits radiographic progression: primary results from the randomised, double-blind, phase III FUTURE 5 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:890–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van der Heijde D, Mease PJ, Landewé RBM. et al. Secukinumab provides sustained low rates of radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from a phase 3 study, FUTURE 5. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:1325–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cawson MR, Mitchell SA, Knight C. et al. Systematic review, network meta-analysis and economic evaluation of biological therapy for the management of active psoriatic arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Lefebvre C, Scherer R.. Handsearching versus electronic searching to identify reports of randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;2:MR000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scherer RW, Saldanha IJ.. How should systematic reviewers handle conference abstracts? A view from the trenches. Syst Rev 2019;8:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook.

- 38. Efthimiou O, White IR. The dark side of the force: Multiplicity issues in network meta-analysis and how to address them. Res Synth Methods 2020;11:105–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are sourced from the public domain and are available in the articles cited throughout.