Abstract

Despite possessing attractive features such as autotrophic growth on minimal media, industrial applications of cyanobacteria are hindered by a lack of genetic manipulative tools. There are two important features that are important for an effective manipulation: a vector which can carry the gene, and an induction system activated through external stimuli, giving us control over the expression. In this study, we describe the construction of an improved RSF1010-based vector as well as a temperature-inducible RNA thermometer. RSF1010 is a well-studied incompatibility group Q (IncQ) vector, capable of replication in most Gram negative, and some Gram positive bacteria. Our designed vector, named pSM201v, can be used as an expression vector in some Gram positive and a wide range of Gram negative bacteria including cyanobacteria. An induction system activated via physical external stimuli such as temperature, allows precise control of overexpression. pSM201v addresses several drawbacks of the RSF1010 plasmid; it has a reduced backbone size of 5189 bp compared to 8684 bp of the original plasmid, which provides more space for cloning and transfer of cargo DNA into the host organism. The mobilization function, required for plasmid transfer into several cyanobacterial strains, is reduced to a 99 bp region, as a result that mobilization of this plasmid is no longer linked to the plasmid replication. The RNA thermometer, named DTT1, is based on a RNA hairpin strategy that prevents expression of downstream genes at temperatures below 30 °C. Such RNA elements are expected to find applications in biotechnology to economically control gene expression in a scalable manner.

Keywords: Plasmid vector, Cyanobacteria, RNA thermometer

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Development of shortened broad host range vector.

-

•

Mobilization of plasmid is controlled by a single RP4 oriT.

-

•

Development of temperature inducible RNA thermometer fit for use in cyanobacteria.

1. Introduction

Cyanobacteria have gained attention as chassis organisms for cheap and sustainable production of raw fuels and biological molecules, thanks to their ability to use CO2 and sunlight as their main sources of carbon and energy respectively [1]. Their ability to grow autotrophically makes many precursor molecules naturally available that otherwise need to be supplied externally when dealing with bacterial bioprocesses. However, there is a dearth of knowledge and tools designed specifically for controlled genetic manipulation of cyanobacteria. Plasmids such as ColE1, p15A, pMB1 and pSC101 have been the workhorses of genetic studies and a tool for expression of foreign genes in Escherichia coli; the availability of such tools led to most of our understanding of genes and their function. The progress in molecular biotechnology could not be so rapid without development of suitable plasmid tools as cloning and expression vectors [2,3]. Unfortunately, cyanobacterial biotechnology lacks a repertoire of shuttle plasmid vectors that are available for use in other organisms such as E. coli. Cyanobacterial genetic engineering largely depends on the integration of heterologous DNA into neutral sites/regions of the cyanobacterial genome. Genetic manipulations of Synechococcus PCC 7942 [4,5], PCC 6301 [4], 7002 [6], Synechocystis PCC 6803 [7], Anabaena PCC 7120 [8] have been reported using this methodology. Recent developments in integration of DNA into cyanobacteria were directed toward standardizing the construction of integrative vectors. Standards such as SyneBrick [5] and Bglbrick [9] have been proposed, allowing quick and easy interchange of parts such as promoters, Ribosomal Binding Site (RBS), gene of interest and terminators.

Replicative plasmids in cyanobacteria can be broadly categorised into either RSF1010 based vectors or native cyanobacterial plasmids that have been modified to replicate in E. coli by addition of E. coli replicons [10,11]. Although the availability of integrative plasmids has fulfilled the basic requirement for gene expression in model cyanobacteria, yet there is a need for replicative vectors, as they possess some advantages that cannot be provided by integrative vectors. Since most cyanobacteria are polyploid, any genetic manipulation to the genome that is dependent on recombination must carry out a few rounds of segregation. These rounds of segregation are time consuming depending on the growth rate of the cyanobacterial strain. Replicative vectors on the other hand, do not need to be segregated since they replicate independently and transformed cyanobacteria that do not possess this plasmid can be negatively selected by antibiotics. RK2 origin of replication is another family of broad host range plasmids belonging to the IncP incompatibility group. The use of RK2 replicon based plasmids has been shown in Synechocystis PCC 6803, and has a lower copy number compared to RSF1010 replicon based plasmids [12]. Broad host range replicons can be used to prospect wild cyanobacterial strains in the laboratory for production of biotechnologically important chemicals/natural products, as described recently in Ref. [13]. In addition to overcoming the time constraints of segregation, plasmids also allow higher levels of gene expression and are the preferred tools for large sized genes [14,15]. Cases such as CRISPR- Cas editing of genomes or use of recombinases require expression of genes for only a short period of time; replicative vectors that can be cured from the host organism upon induction are perfect for such applications.

The natural RSF1010 is an 8684 bp plasmid that has overlapping regulatory regions and overlapping genes; it has evolved to replicate in a wide range of hosts and is not attacked by most restriction modification systems of host bacteria. The proteins RepB′, RepA and RepC are involved in the replication of this plasmid [16,17], and mobA, mobB, and mobC are genes involved in relaxosome formation required for mobilization of RSF1010 from ori T. There are 4 promoters involved in the regulation of RSF1010 replication, copy number and mobilization named P1, P2, P3 and P4. The promoters P1 and P3 control the transcription of mobAB and repB. P2 promoter controls the transcription of mobB gene. The promoters P1, P2 and P3 are involved in the control of most of the genes involved in replication and mobilization of RSF1010; the spatial clustering of the promoters allows synchronization between replication and mobilization. P4 promoter controls the transcription of repA and repC in addition to two orfs named gene E and gene F [18].

RSF1010 is a well studied plasmid that has been shown to replicate in several cyanobacterial strains [19,20]. RSF1010 based plasmids such as pRL1383a and pRL1342 have been used mainly in the gene complementation studies of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 and a few other cyanobacteria [21]. Differences in cyanobacterial ecology and adaptation to different conditions makes each cyanobacterial chassis suitable for a particular environment. Availability of a broad host range replicative vector would allow the testing of a genetic construct across multiple hosts and conditions, without major modifications thereby saving time and labour.

In addition to vectors, cyanobacterial biotechnology also needs tightly controlled induction systems that respond to specific stimuli. Despite their potential for photoautotrophic production of metabolites, there is a lack of precisely controlled inducible elements in cyanobacteria. The reason for this is the poor understanding of differences in gene expression control in cyanobacteria compared to their heterotrophic counterparts [22]. Heterologous promoters adapted from other organisms (mainly E. coli) have been designed for use in cyanobacteria as well, but they can suffer from leaky expression [23,24]. Native cyanobacterial promoters show lower level of expression compared to those from heterologous organisms [22]. However, RNA thermometers (RNATs) are a known control element that regulate the translation of heat shock proteins in response to environmental stimuli [25] or are involved with proteins essential for virulence [26]. We describe the construction of a new recombinant plasmid and an RNA thermometer, for genetic manipulation and physical inducer for control of gene expression in cyanobacteria.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Strains and growth conditions

E. coli DH5α λpir was used for all transformations, E. coli S17-1 – λpir was used for conjugation into cyanobacteria. Competent cells were prepared by the Inoue method as described in Refs. [27,28]. E. coli was grown at 37 °C in LB medium (10 g Tryptone, 5 g Yeast extract, 10 g NaCl. Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 was grown in BG11 media (0.75 g/L NaNO3, 0.04 g/L K2HPO4, 0.075 g/L MgSO4 7H2O, 0.036 g/L CaCl2 2H2O, 0.006 g/L citric acid, 0.006 g/L ferric ammonium citrate, 0.001 g/L disodium EDTA, 0.02 g/L Na2CO3, 1 mL/L trace metal mix A5 (2.86 g/L H3BO3, 1.81 g/L MnCl2 4H2O, 0.222 g/L ZnSO4 7H2O, 0.39 g/L NaMoO4 2H2O, 0.079 g/L CuSO4 5H2O, 49.4 mg/L Co(NO3)2 6H2O) in deionized water) at 28 1 °C with 50−0.5 μmol/m−2/s.

2.2. Synthesis of the 298 bp gene fragment

PAGE purified oligos, as described in Table 1 were purchased from IDT (India) and treated with T4-Polynucleotide kinase for 1 h at 37 °C to replace the 5′-OH group of synthetic oligos with Phosphate. The phosphorylated oligos were assembled using Ligase Chain Reaction; briefly, 20 pmol of primers were added to 50 μL reaction mixture containing T4 DNA ligase (Purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Mumbai, India) in the presence of 50% PEG 4000 as a crowding agent. The reaction mixture was then cycled 10 times (95 °C for 15 s; 55 °C for 30 s ramp rate of 0.5 °C/s; 20 °C for 10 min) at this point, 1 μL (5 Weiss units) of T4 DNA ligase, was added and cycled 5 times (95 °C for 15 s ramp rate of 0.5 °C/s; 55 °C for 15 s; 20 °C for 10 min) the 5 cycle step was repeated two more times after addition of T4 DNA ligase. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 65 °C for 10 min and slowly cooled to 4 °C at a ramp rate of 0.1 °C/s. The desired fragment was rescued by amplification with PCR, followed by cloning and sequencing.

Table 1.

List of oligonucleotides4designed and used in this study.

| Oligo name | Oligonucleotide sequence | Length |

|---|---|---|

| pSynthetic.01 | 5′-GAA TAA GGG ACA GTG AAG AAG GAA CAC CCG CTCGCG-3′ | 36 |

| pSynthetic.02 | 5′-AGG TGA AGT AGG CCC ACC CGC GAG CGG GTG TTC CTT-3′ | 36 |

| pSynthetic.03 | 5′-GGT GGG CCT ACT TCA CCT ATC CTG CCC GGC TGA CG-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.04 | 5′-CCT TGG TGT ATC CAA CGG CGT CAG CCG GGC AGG AT3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.05 | 5′-CCG TTG GAT ACA CCA AGG AAA GTC TAC AAA AAA AG-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.06 | 5′-GCC CGC CTA ATG AGC GGG CTT TTT TTG TAG ACT TT-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.07 | 5′-CCC GCT CAT TAG GCG GGC TTG ACA ATT AAT CAT CG-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.08 | 5′-GAA TTC CAT TAT ACG AGC CGA TGA TTA ATT GTC AA-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.09 | 5′-GCT CGT ATA ATG GAA TTC GAT ATC AAG CTT GGA TC-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.10 | 5′-TAG CTT TCG CTA AGG ATG GAT CCA AGC TTG ATA TC-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.11 | 5′-CAT CCT TAG CGA AAG CTA AGG ATT TTT CTT AAC CA-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.12 | 5′-AAC AAT GGG GTG TCA AGA TGG TTA AGA AAA ATC CT -3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.13 | 5′-TCT TGA CAC CCC ATT GTT AAT GTT GCT TGC GTT GG -3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.14 | 5′-GTA TAA CAG GCG TGA GTA CCA ACG CAA GCA ACA TT -3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.15 | 5′-TAC TCA CGC CTG TTA TAC TAT GAG TAC TCT AGT GG-3′ | 35 |

| pSynthetic.16 | 5′-TGT CAC CTC CTT CAC CTC CAC TAG AGT ACT CAT A-3′ | 34 |

| pRL1383a FWD (1) | 5′-TGG AGG TGA AGG AGG TGA CAA TGA AGA ACG ACA GGA CTT TGC AGG C -3′ | 46 |

| pRL1383a WD (2) | 5′GGC CCA AGG CGG CAG GCT GAG ACA GAA ATG CCT CGA CTT C -3′ | 40 |

| pRL1383a FWD (3) | 5′-CAA TTC GTT CAA GCC GAC GCC GCG TCC TTG CAA TAC TGT G -3′ | 40 |

| pRL1383a REV (1) | 5′-GAA GTC GAG GCA TTT CTG TCT CAG CCT GCC GCC TTG GGC C -3′ | 40 |

| pRL1383a REV (2) | 5′-CAC AGT ATT GCA AGG ACG CGG CGT CGG CTT GAA CGA ATT G -3′ | 40 |

| pRL1383a REV (3) | 5′-TTC TTC ACT GTC CCT TAT TCA AGG ATG AGC CGG GCT GAA T-3′ | 40 |

| Synthetic re- gion FWD | 5′-ATT CAG CCC GGC TCA TCC TTG AAT AAG GGA CAG TGA AGA AGG-3′ | 42 |

| Synthetic re- gion REV | 5′-AAA GTC CTG TCG TTC TTC ATT GTC ACC TCC TTC ACC TCC A -3′ | 40 |

| DTT1(+) | 5′-ACC TCC TTA ACG GCT TCC TGA AGG AGG TAA GGA GGT ATA CAT-3′ | 42 |

| DTT1(−) | 5′-ATG TAT ACC TCC TTA CCT CCT TCA GGA AGC CGT TAA GGA GGT-3′ | 42 |

| DTT2(+) | 5′-ACC TCC TTT CGC GTA ATA TAA GGA GGT ATA TAC AT-3′ | 35 |

| DTT2(−) | 5′-ATG TAT ATA CCT CCT TAT ATT ACG CGA AAG GAG GT-3′ | 35 |

| DTTGFPF | 5′-AAT GGA ATT CAC CTC CTT AAC GGC-3′ | 24 |

| DTTGFPR | 5′-TCC AAG CTT ATT TGT ATA GTT CAT CCA TG-3′ | 29 |

2.3. PCR amplification of plasmid parts

The parts required for plasmid replication, antibiotic resistance, origin of replication, and the syn- thetic fragment constructed above were named fragment 1, 2, 3 and SREG respectively. Fragment 1, 2 and 3 were amplified using two step PCR using the primer pairs (pRL1383a FWD(1), (pRL1383a REV(1)), (pRL1383a FWD(2), pRL1383a REV(2)), (pRL1383a FWD(3), pRL1383a REV(3)). Initial denaturation was performed at 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 90 s; followed by final extension at 72 °C for 2 min.

2.4. Assembly of the plasmid vector

The DNA fragments named fragments 1, 2, 3 and SREG amplified as described above, were incubated at 37 °C with T4 DNA polymerase for 5 min in T4 polymerase buffer. The fragments were incubated at 75 °C to inactivate T4 DNA polymerase. The reaction components were then cooled to 60 °C at a rate of 0.1 °C/s and incubated for 30 min, then cooled to 45 °C. The ends were repaired by adding Taq DNA polymerase and incubating at 72 °C for 2 min, followed by ligation with T4 DNA ligase, supplemented with ATP at 37 °C for 20 min. The reaction mixture was purified using PCR purification kit and checked by gel electrophoresis. 5 μL of this reaction was used to transform E. coli DH5α competent cells. Transformants were selected on LB plates containing 50 mg/L Streptomycin. Fig. 1 depicts the assembled plasmid pSM201v.

Fig. 1.

Vector map of pSM201v, rep genes were derived from the RSF1010 backbone and placed under the control of the native P4 promoter, the mob genes were replaced by the RP4 oriT reducing the size of the vector, while maintaining the ability to transfer via mobilization with an E. coli mating helper strain.

2.5. Expression of GFP under the control of DTT1 and conjugal transfer of pSM201v::DTT1-GFP

The CDS of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) was cloned downstream of DTT1, under the control of tac promoter of pSM201v. lacI has not been provided in the plasmid and does not exist in PCC 7942, hence the gene expression from tac promoter is constitutive. Plasmid DNA was pre- pared by double digestion of pSM201v with EcoRI and HindIII. The DTT1-GFP was amplified by using the primer pair, DTTGFPF and DTTGFPR, whose sequences have been mentioned in Table 1. This construct was first generated in E. coli DH5α and then transformed into E. coli S17-1 λpir to prepare for conjugation in both cases, the transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with 50 mg/L of Streptomycin. Conjugal transfer of pSM201v was performed by mixing 500 μL of E. coli S17-1 λpir washed and resuspended in BG-11, with 500 μL of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. The cell suspension was passed through 0.22 μm nylon filter membrane and aseptically transferred to BG11 without selection antibiotics. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were resuspended in BG-11 medium and plated on BG-11 containing 10 mg/L Streptomycin. The transformants obtained were tested for presence of plasmid by PCR, plasmid isolation and restriction digestion; positive colonies were propagated in BG-11 medium supplemented with 25 mg/L Streptomycin for fluorescence microscopy. Conjugation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of number of cells transformed after conjugation divided by the number of recipients.

PCC 7942 cells harbouring pSM201-DTT1-GFP were grown to log phase, then the seed culture was inoculated into six identical flasks. pSM201v vector does not contain lacI gene, allowing for constitutive expression in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. After the OD750 value reached 0.4, three flasks were placed in an incubator shaker set at 37 ± 1 °C and the rest of the flasks were placed at 28 ± 1 °C. After 12 h of incubation, the cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

2.6. Design and characterization of temperature inducible RNA

In order to create a synthetic temperature inducible RNA, a list of all possible 42 bp long RNA with random nucleotides between the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence and anti-SD were generated using a python script; among them 100 sequences were randomly selected for screening based on the energy predicted by the program RNAfold found in the vienna RNA package [29]. Two sequences were found that had a predicted folding energy lower than −10 kcal/mol to exclude sequences that do not form a stable secondary structure. These oligonucleotides were named DTT1 and DTT2, and synthesised by IDT (India). The oligos were resuspended in equimolar mixture and annealed slowly, to form double stranded DNA. This dsDNA was ligated with RFP – obtained from the plasmid mCherry-pBAD (Addgene plasmid # 54630), amplified by PCR and inserted into the vector pSYN_1 under the control of Psc promoter and sequenced. The Psc promoter is a weak constitutive promoter derived from Synechocystis [30]. E. coli DH5α was transformed with the pSYN_1-DTT1-RFP and pSYN_1-DTT2-RFP plasmids. The resulting transformants were grown in LB broth and incubated at 25, 30, 37 and 42 °C to study RFP expression characteristics.

2.7. Conjugal transfer of pSM201v and restriction digestion

E. coli S17-1 cells transformed with pSM201v were grown in the presence of appropriate antibiotics. Conjugal transfer of pSM201v was performed as described in the section above, briefly by mixing 500 μL of E. coli S17-1 with S. elongatus PCC 7942. The exconjugants were selected on BG-11 plates supplemented with 25 mg/L Streptomycin. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the method of Birnbiom and Doly [31]. The plasmid DNA isolated from PCC 7942 Was digested with HindIII, EcoRI, BamHI and PsuI restriction enzymes to confirm the stability and ability of pSM201v to replicate in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Features of pSM201v

The lack of tools for cyanobacterial genetic manipulation led us to construct novel improved cloning and expression vector pSM201v. Our goal was to reduce the size of the vector to allow cloning/expression of larger DNA fragments/genes in the host organism. There are multiple reports of native RSF1010 and its derivatives in cyanobacteria. Vectors such as pFC1, pMB13, pKT210 have been reported to replicate in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 & PCC 6714 and Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 & PCC 6301 but are quite large which makes them difficult to transform and manipulate [32]. Some groups have created a non-mobilizable variant of RSF1010 but have used the PlacUV 5 promoter to replace the P1, P2 and P3 promoters of the RSF1010 vector [18,33]. Although there is significant size reduction, the use of lacUV5 promoter with non-optimal Shine-Dalgarno site (5′- GGGGGG-3′) in Ref. [18] or 5′-CGGGCCACCAAGCGATTCCCACAC-3′ in Ref. [33], adds another layer of complexity and may yield undesirable consequences when dealing with cyanobacteria that have been modified to express the lacI gene [34]. LacI is a well studied and widely applied repressor protein, and its inducers d-Lactose and IPTG are commonly available in many labs, because of their importance and relatively low cost. Thus, we searched for a replacement promoter to drive the expression of RepBAC genes. Gene F is present on the RSF1010 plasmid that encodes an auto-regulatory protein that binds to the operator regions located in promoter P4 [35]. We have placed the repB′ under the control of P4 promoter, allowing control of copy number independent of host machinery. The synthetic fragment mentioned as SREG in section 2.4, contains a 99 bp oriT-RP4 derived from RP4 plasmids allowing conjugal transfer of pSM201v by strains expressing tra genes. Commonly available strains of E. coli S17-1/SM10 can transfer pSM201v by conjugation to cyanobacteria [36].

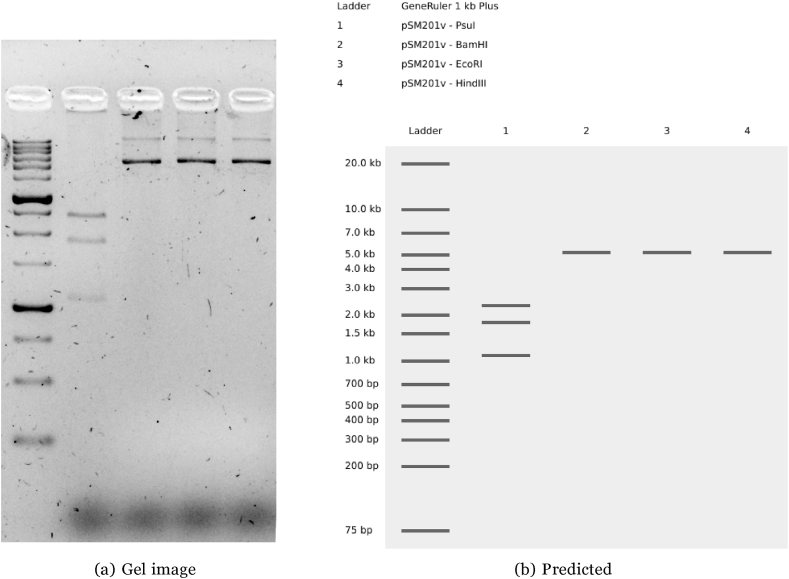

3.2. Confirmation of pSM201v replication in PCC 7942 by plasmid isolation and restriction digestion

The plasmid pSM201v isolated from transformed PCC 7942 showed expected pattern after digestion with EcoRI, HindIII, BamHI and PsuI (as shown in Fig. 2). This shows that the plasmid is capable of stable replication in cyanobacteria, as well as conjugation when required factors are supplied in trans.

Fig. 2.

Electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose digestion of pSM201v isolated from Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 with EcoRI, HindIII, BamHI, and PsuI. (The uncropped image is available as supplementary figure “Gel image 2018-11-23.tif”).

3.3. The heat inducible RNA element – DTT1

RNA thermometers add another layer of control over gene expression at translational level. RNA thermometers are controlled by temperature, which is a physical phenomenon, hence they are not dependent on host machinery, or external chemical inducers. This independence on host transcription machinery is expected to standardize the expression of genes across genera under the control of RNA thermometers. The 42 nt RNA thermometer of Synechocystis PCC 6803 is a simple, natural RNAT that fully expresses at 42 °C and is repressed below 28 °C [37]. This is a potent tool to control gene expression in cyanobacteria, and availability of RNATs with diverse expression profiles aids in control of gene expression. In addition to Synechocystis PCC 6803 heat shock protein RNAT, we wanted to make another RNAT available to expand cyanobacterial toolbox. Upon screening several RNA hairpins for RNAT activity, we found that DTT1 had the most favourable temperature-expression profile for gene expression control in cyanobacteria. This is a powerful tool to control gene expression in cyanobacteria, in addition to Synechocystis PCC 6803 heat shock protein RNAT, we have designed DTT1 with a different temperature - expression profile. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, DTT1 has a stable hairpin structure. DTT1 represses gene expression below 30 °C and is active at 37 °C and above (as shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5), as can be inferred from the temperature vs fluorescence data described in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Minimum free energy structure of DTT1.

Fig. 4.

Expression of RFP in E. coli DH5α under the control of DTT1 at various temperatures, 25 °C and 30 °C were unable to induce the expression of RFP, while temperature of 37 °C and above allowed the expression of RFP.

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence microscopy images of GFP induced and GFP uninduced PCC 7942 trans- formed with pSM201v-DTT1-GFP, red cells indicate the autofluorescence caused by chlorophyll of cyanobacteria. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Fluorescence intensity of RFP expressed in E. coli DH5α under the control of DTT1 at various temperatures.

| Temperature in °C | Fluorescence intensity (a.u.) |

|---|---|

| 30 | 639 ± 76 |

| 37 | 16,452 ± 957 |

| 42 | 24,552 ± 1566 |

3.4. Gene expression studies in cyanobacteria

We introduced the plasmid pSM201v-DTT1-GFP into the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus elongatus PCC, via conjugal transfer using E. coli S17-1 λpir. It was found that the conjugation efficiency using this plasmid system was about 1.49 0.87 × 10−7. After screening the transformants, PCC 7942 containing the pSM201v:DTT1-GFP plasmid was used to study the gene expression. GFP was used to study the gene expression rather than RFP because of the interfering background autofluorescence in cyanobacteria. After allowing the transformed cyanobacteria to grow to OD750 of 0.4 in the presence of Streptomycin, cells were divided equally and transferred to temperatures of 28 °C and 37 °C under equal illumination. When the cells were visualized under fluorescent microscope, it was observed that there was no expression of GFP at 28 °C, the portion of cells incubated at 37 °C showed the expression of GFP.

4. Conclusions

The advances in gene assembly technologies such as Gibson assembly, Sequence and ligase in- dependent cloning (SLIC), Polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) and various other seamless cloning technologies have given us the ability to synthesize almost unconstrained DNA sequences, which were difficult to construct earlier, In this study we have created a minimal version of RSF1010, which is one of the widely used broad host range vectors known to replicate in lot of bacteria including cyanobacteria. Here we report the construction of RSF1010 backbone with reduced backbone size of 5189 bp and a temperature inducible RNA element DTT1. The tem perature inducible RNA element, represses the downstream gene when the temperature is below 30 °C. Such RNA based control elements can be used to construct temperature sensitive mutants for reverse genetics studies. The plasmid developed in this study is available through Addgene, plasmid #171860.

Author contribution statement

Vamsi Bharadwaj S. V.: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Diptee S. Tiwari: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Tonmoy Ghosh: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Sandhya Mishra, Ph.D.: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Funding statement

Dr. Tonmoy Ghosh acknowledges financial support from the Science and Engineering Research Board, New Delhi (grant no. PDF/2021/000144)

Data availability statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at addgene under the accession number Addgene plasmid #70692.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Wolk for pRL1383a (Addgene plasmid #70692), Dr. Michael Davidson for mCherry-pBAD (Addgene plasmid #54630). TG would like to acknowledge SERB, New Delhi for NPDF (File no. PDF/2021/000144). The authors would like to thank Dr. Imran Pancha for his support and constructive advice. This manuscript has been assigned PRIS number CSIR-CSMCRI – 096/2018.

References

- 1.Machado Iara MP., Atsumi Shota. Cyanobacterial biofuel production. J. Biotechnol. 2012;162(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarence I Kado. Historical events that spawned the field of plasmid biology. Plasmid: Biol. Impact Biotechnol. Discov. 2015:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helinski Donald R. Introduction to plasmids: a selective view of their history. Plasmid Biol. 2004:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsinoremas Nicholas F., Alan K Kutach, Strayer Carl A., Golden Susan S. Efficient gene transfer in Synechococcus sp. strains PCC 7942 and PCC 6301 by interspecies conjugation and chromosomal recombination. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176(21):6764–6768. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6764-6768.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Wook Jin, Lee Sun-Mi, Um Youngsoon, Sim Sang Jun, Han Min Woo. Development of synebrick vectors as a synthetic biology platform for gene expression in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:293. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anne M Ruffing, Jensen Travis J., Lucas M Strickland. Genetic tools for advancement of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 as a cyanobacterial chassis. Microb. Cell Factories. 2016;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreps Sabine, Ferino Fabrice, Mosrin Christine, Gerits Jozef. Max Mergeay, and Pierre Thuriaux. Conjugative transfer and autonomous replication of a promiscuous IncQ plasmid in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG. 1990;221(1):129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar Chaurasia Akhilesh, Parasnis Anjali, Apte Shree Kumar. An integrative expression vector for strain improvement and environmental applications of the nitrogen fixing cyanobacterium, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2008;73(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taek Soon Lee Rachel A Krupa, Zhang Fuzhong, Hajimorad Meghdad, Holtz William J., Prasad Nilu, Sung Kuk Lee, Keasling Jay D. Bglbrick vectors and datasheets: a synthetic biology platform for gene expression. J. Biol. Eng. 2011;5(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armshaw Patricia, Carey Dawn, Sheahan Con, Pembroke J Tony. Utilising the native plasmid, pca2. 4, from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 as a cloning site for enhanced product production. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2015;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0385-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Yu, Alvey Richard M., Byrne Patrick O., Joel E Graham, Shen Gaozhong, Bryant Donald A. Photosynthesis Research Protocols. Springer; 2011. Expression of genes in cyanobacteria: adaptation of endogenous plasmids as platforms for high-level gene expression in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002; pp. 273–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasudevan Ravendran, Gale Grant AR., Schiavon Alejandra A., Puzorjov Anton, Malin John, Gillespie Michael D., Vavitsas Konstantinos, Zulkower Valentin, Wang Baojun, Howe Christopher J., et al. Cyanogate: a modular cloning suite for engineering cyanobacteria based on the plant moclo syntax. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(1):39–55. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryan Bishé, Arnaud Taton, Golden James W. Modification of RSF1010-based broad- host-range plasmids for improved conjugation and cyanobacterial bioprospecting. iScience. 2019;20:216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen You, Arnaud Taton, Go Michaela, Ross E London, Pieper Lindsey M., Golden Susan S., Golden James W. Self-replicating shuttle vectors based on pans, a small endogenous plasmid of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Microbiology. 2016;162(12):2029–2041. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griese Marco, Lange Christian, Soppa Jörg. Ploidy in cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011;323(2):124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherzinger Eberhard, Haring Volker, Lurz Rudi, Otto Sabine. Plasmid RSF1010 DNA replication in vitro promoted by purified RSF1010 RepA, RepB and RepC proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(6):1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherzinger Eberhard, Bagdasarian Miroslawa M., Scholz Peter, Lurz Rudolf, Rückert B., Bagdasarian Michael. Replication of the broad host range plasmid RSF1010: requirement for three plasmid-encoded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81(3):654–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.I Katashkina Joanna, Kuvaeva Tatiana M., Andreeva Irina G., Yu Skorokhodova Alexandra, Irina V Biryukova, L Tokmakova Irina, Golubeva Lubov I., Sergey V Mashko. Construction of stably maintained non-mobilizable derivatives of RSF1010 lacking all known elements essential for mobilization. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sode Koji, Tatara Masahiro, Takeyama Haruko, Burgess J Grant, Matsunaga Tadashi. Conjugative gene transfer in marine cyanobacteria: Synechococcus sp., Synechocystis sp. and Pseudanabaena sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1992;37(3):369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00210994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer Richard. Replication and conjugative mobilization of broad host-range IncQ plasmids. Plasmid. 2009;62(2):57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolk C Peter, Fan Qing, Zhou Ruanbao, Huang Guocun, Lechno-Yossef Sigal, Kuritz Tanya, Wojciuch Elizabeth. Paired cloning vectors for complementation of mutations in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Arch. Microbiol. 2007;188(6):551–563. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0276-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Till Petra, Toepel Jörg, Bruno Bühler, Mach Robert L., Mach-Aigner Astrid R. Regulatory systems for gene expression control in cyanobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;104(5):1977–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10344-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Hsin-Ho, Peter Lindblad. Wide-dynamic-range promoters engineered for cyanobac- teria. J. Biol. Eng. 2013;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerrero Fernando, Carbonell Verónica, Cossu Matteo, Correddu Danilo, Patrik R., Jones Ethylene synthesis and regulated expression of recombinant protein in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cimdins Annika, Klinkert Birgit, Aschke-Sonnenborn Ursula, Kaiser Friederike M., Ko- rtmann Jens, Narberhaus Franz. Translational control of small heat shock genes in mesophilic and thermophilic cyanobacteria by RNA thermometers. RNA Biol. 2014;11(5):594–608. doi: 10.4161/rna.28648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandra Krajewski Stefanie, Narberhaus Franz. Temperature-driven differential gene ex- pression by RNAthermosensors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2014;1839(10):978–988. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green Michael R., Joseph Sambrook. The inoue method for pRepAration and transformation of competent Escherichia coli :“ultracompetent” cells. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2020;(6) doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot101196. pdb–prot101196, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue Hiroaki, Nojima Hiroshi, Okayama Hiroto. High efficiency transformation of Es- cherichia coli with plasmids. Gene. 1990;96(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorenz Ronny, Bernhart Stephan H., Siederdissen Christian Höner zu, Tafer Hakim, Flamm Christoph, Stadler Peter F., Ivo L Hofacker. Viennarna package 2.0. Algorithm Mol. Biol. 2011;6(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan Simkovsky, Daniels Emy F., Tang Karen, Huynh Stacey C., Golden Susan S., Brahamsha Bianca. Impairment of o-antigen production confers resistance to grazing in a model amoeba–cyanobacterium predator–prey system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(41):16678–16683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214904109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birnboim H.C., Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening plasmid recombinant dna. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:15–19. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mermet-Bouvier Pierre, Chauvat Franck. A conditional expression vector for the cyanobac- teria Synechocystis sp. strains PCC6803 and PCC6714 or Synechococcus sp. strains PCC7942 and PCC6301. Curr. Microbiol. 1994;28(3):145–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01571055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva-Rocha Rafael, Martínez-García Esteban, Calles Belen, Chavarría Max, Arce- Rodríguez Alejandro, de Las Heras Aitor, Paez-Espino A David. Gonzalo Durante-Rodríguez, Juhyun Kim, Pablo I Nikel, et al. The standard european vector architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D666–D675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camsund Daniel, Heidorn Thorsten, Peter Lindblad. Design and analysis of laci-repressed promoters and dna-looping in a cyanobacterium. J. Biol. Eng. 2014;8(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maeser Stefan, Scholz Peter, Otto Sabine, Scherzinger Eberhard. Gene f of plasmid RSF1010 codes for a low-molecular-weight repressor protein that autoregulates expression of the rep ac operon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(21):6215–6222. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon R.U.P.A.P., Priefer U., Pühler Alfred. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology. 1983;1(9):784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kortmann Jens, Simon Sczodrok, Rinnenthal Jörg, Schwalbe Harald, Narber- haus Franz. Translation on demand by a simple rna-based thermosensor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(7):2855–2868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at addgene under the accession number Addgene plasmid #70692.