Abstract

The challenging circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic caused a regression in baseline health of disadvantaged populations, including individuals with frail syndrome, older age, disability, and racial-ethnic minority status. These patients often have more comorbidities and are associated with increased risk of poor postoperative complications, hospital readmissions, longer length of stay, nonhome discharges, poor patient satisfaction, and mortality. There is critical need to advance frailty assessments to improve preoperative health in older populations. Establishing a gold standard for measuring frailty will improve identification of vulnerable, older patients, and subsequently direct designs for population-specific, multimodal prehabilitation to reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Rehabilitation, Prehabilitation, Surgery, Disability, COVID-19, Long COVID, Postacute sequelae SARS CoV2, Pandemic

Key points

-

•

Comorbid, older populations including individuals with frail syndrome, disability, or racial-ethnic minority status are associated with higher rates of postoperative complications, hospital readmissions, longer length of stay, nonhome discharges, mortality, and poor patient satisfaction.

-

•

Surgical prehabilitation may improve poor postoperative outcomes of acute and nonacute surgery for high-risk surgical candidates within older patients.

-

•

Standardization of frailty tools and multimodal prehabilitation programs can enhance identification of comorbid, older patients and reduce postoperative risks and mortality.

-

•

Use of the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach could help establish clinical guidelines for prehabilitation.

Introduction

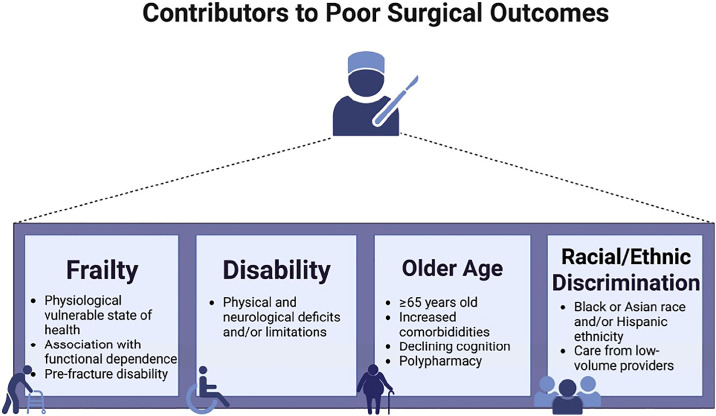

The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in late 2019, led to significant changes in surgical care. Profound delays in timing of operations, along with a confluence of unprecedented conditions contributed to the deteriorating health of many individuals across various populations. Despite unforeseen adverse outcomes, the cancellations and postponements of elective surgeries were part of heightened efforts to prioritize safety concerns. Simultaneously, mandates were enforced for home isolation and social distancing in public places, such as gyms, parks, and local schools, resulting in an increase in sedentary lifestyles. Widespread shortages in products combined with the collapse of the prepandemic transportation infrastructure has also limited access to nutritious food for some individuals; whereas, consumption of alcohol has increased.1 The plethora of pandemic-related issues have exacerbated a situation in which surgical outcomes may be negatively impacted beyond known factors, such as frailty, older age, disability, and minority race/ethnicity status (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Contributors to poor surgical outcomes in acute and nonacute surgery.

Prehabilitation may be an antidote to decreasing surgical risk, especially for vulnerable populations, such as people who are older, frail, or disabled. Those with comorbidities, such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other medical conditions that may affect surgical outcomes, might also benefit. High morbidity and mortality during or after surgery is an important concern, particularly in vulnerable populations. For example, a study by Shinall and colleagues2 examined veterans who underwent a noncardiac surgical procedures at Veterans Health Administration Hospitals and found that patients with higher levels of frailty had higher mortality at 30, 90, and 180 days after surgery. Mortality increased as frailty, time, and operative stress increased. Another study assessed patients undergoing noncardiac procedures and found that frailty was associated with higher mortality at 30 and 180 days for all noncardiac surgical specialties regardless of operative stress.3

Individuals with disabilities may also benefit from prehabilitation. Multiple studies have suggested that higher preoperative level of disability is associated with worse surgical outcomes.4, 5, 6 For instance, Mazzola and colleagues7 compared individuals between age 85 and 89 years with those greater than 90 years that underwent hip fracture surgery. Prefracture disability was found to be a predictor of higher rates of mortality in those greater than 90 years old. Afilalo and colleagues4 found that the addition of disability and frailty to cardiac surgery risk scores improved model discrimination of individuals at higher risk for cardiac surgery. Outcomes in spine surgery have been tied to disability-related issues (Table 1 ). In one study, higher preoperative disability was a risk factor for worsening postoperative disability after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis.5 However, individuals with higher preoperative disability were also more likely to have clinically significant improvement in disability after surgery. In a cohort of patients undergoing minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, patients with preoperative disability were more likely to report worse postoperative outcomes and patient satisfaction.6

Table 1.

Disparities in outcomes after spinal surgery9

| Factor/Outcome Measure | Disparity |

|---|---|

| Spinal surgery utilization | Lower rates of surgery in Black, Hispanic, and non-White patients |

| Length of stay | Increased intensive care unit and overall length of stay in Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients |

| In-hospital mortality | Higher in non-White patients and Black patients |

| Complication rates | Increased in Black patients after spinal surgery, including higherrates of bleeding and infection |

Data from [Cardinal T, Bonney PA, Strickland BA, et al. Disparities in the Surgical Treatment of Adult Spine Diseases: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurgery. 2022;158:290-304.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.121].

Individuals who identify with racial or ethnic minority groups are also known to have worse surgical outcomes (see Table 1). For example, a recent systematic review examining 63 studies in total joint arthroplasty (TJA) reported that despite being less likely to undergo TJA, Black patients had higher rates of complications, readmissions, mortality, nonhome discharges, and longer lengths of stay (LOS) compared with White patients.8 Hispanic patients also used TJA less but had higher rates of complications, prolonged LOS, and nonhome discharges. Asian patients had longer LOS but fewer readmissions. Cardinal and colleagues9 focused on disparities in the surgical treatment of adult spine conditions. In this systematic review, the authors noted that despite individuals from minority groups having lower spinal surgery utilization rates, they were more likely to undergo surgery from low-volume providers, and had greater LOS and more complications. Black patients had higher rates of mortality and reported lower outcomes at discharge than White patients. Individuals from certain racial and ethnic minority groups often have more comorbidities, such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, which may make surgeons concerned about the potential risks of surgery in these patients. Prehabilitation might help to reduce their risk profile and support more access to operative interventions.

Discussion

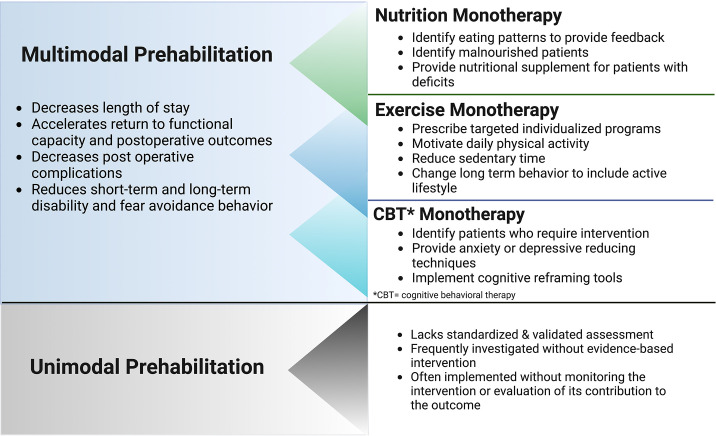

Prehabilitation improves patients’ physical and mental function, through buffering the deconditioning between the time of diagnosis and recovery. Such mechanisms as accessibility, motivation, role of health care professionals and organizations, acceptability, and prioritization have been shown to improve physical fitness, reduce LOS, reduce delay for surgery, reduce postoperative complications, and improve quality of life.10 In order for health care professionals to deliver and engage in prehabilitation, there needs to be strong evidence-based protocols for implementation and clinical practice in a multidisciplinary system that provides specific guidance for screening and triage of patients. Numerous studies have investigated unimodal prehabilitation intervention, with exercise being the most studied (Fig. 2 ). Other interventions have included nutritional, educational, psychological, or clinical components.10, 11, 12 However, a single prehabilitation literature review on nutrition within oncology research revealed a lack of standardization and validation of nutritional assessment. Investigation of this model frequently revealed inadequate evidence-based intervention that failed to include monitoring or evaluation of its outcome.13 Development of core outcomes could improve the quality of unimodal prehabilitation studies to enable pooling of evidence and address research gaps. Although unimodal prehabilitation, such as exercise, can improve functional capacity and reduce complication rates, the evidence of effectiveness ranges from very low to moderate because of relegating serious risk of bias, imprecision, and inconsistency.12

Fig. 2.

Describes prehabilitation program designs and potential benefits and disadvantages of multimodal versus unimodal prehabilitation. These are general comments based on the available research. Further investigation is needed. CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

More recent studies have assessed multimodal prehabilitation programs, which include multiple preoperative interventions to prepare patients for surgery with the goal of improving resilience and postoperative outcomes (see Fig. 2). Although a single prehabilitation intervention, such as nutrition alone (oral nutritional supplements with and without counseling) has been shown to significantly decrease LOS, evidence of multimodal prehabilitation combining exercise (oral nutritional supplements with and without counseling and with exercise) suggests an accelerated return to presurgical functional capacity.14 Because there is often a waiting period before elective surgical procedures, multimodal prehabilitation provides an opportunity to intervene in a targeted fashion to improve postoperative recovery. Active engagement of the patient in the multimodal prehabilitation including exercise, nutrition, and psychological well-being may alleviate the physical and emotional distress presurgery and postsurgery.15 A meta-analysis study on colorectal cancer surgery reveals that multimodal prehabilitation comprising at least two preoperative interventions shows improvement in functional capacity and postoperative outcomes.12

However, the included studies did not report a difference between groups for health-related quality of life and LOS. Nevertheless, multimodal programs also increase perioperative functional capacity and potentially decrease postoperative complications in older adults undergoing major abdominal surgery.11 Studies also suggest that multimodal rehabilitation, including exercise and cognitive-based therapy, reduces short- and long-term disability and fear-avoidance behavior following a lumbar fusion surgery. High-quality research that assesses study outcomes is required to confirm the effectiveness of multimodal prehabilitation programs. Furthermore, use of the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach, including critique of bias risk and quality of evidence, could help establish clinical guidelines from prehabilitation research, especially for older adults (Box 1 ).11 , 16

Box 1. The methodology of the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach and its advantages for establishing clinical guidelines.

- GRADE Approach for Establishing Clinical Guidelines16

-

•Use explicit definitions and judgments to reduce strategy error or bias

-

•Systematically assess study designs and confirm a direct relationship to quality of evidence

-

•Consider data precision, confounders, and strength of outcomes and associations

-

•Identify the weakest outcomes to represent the overall quality of evidence for clinical decision-making because this reduces overestimation of data power

-

•Determine relative importance of outcomes (critical vs noncritical vs ignored) to support the quality and strength of clinical recommendations

-

•Pay direct attention to the relationship of health benefits and harms to ensure transparency of net positive health outcomes

-

•Establish summaries of evidence and findings that can provide consistent information for research evaluations

-

•Incorporate international collaborations with a wide spectrum of organizations to develop a sensible, reliable, and generalizable system

-

•

Data from [Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490].

Presurgical frailty and outcomes

As the aging population continues to grow with increasing life expectancy, older adults are predicted to account for 23% of the US population by 2050, with potential to outnumber the percent of children.17 , 18 Unfortunately, hospitalizations are three times as high among older adults (eg, ≥65 years) considering health profiles of increased comorbidities, which are greater in quantity and severity than younger populations.17 , 18 However, the unidimensional clinical use of comorbidity is an inadequate measure of health status because it excludes significant factors, such as functionality, physical endurance, and cognition. The multifactorial components of health are known to impact medical management and surgery.

Numerous studies including systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that frailty is a valuable predictor of poor outcomes in surgical patients (Fig. 1).17 , 19, 20, 21 Frailty is defined as a weakened state of physical function, cognition, and physiologic capacity that precedes disability and vulnerability to stressors (eg, surgery, anesthesia).17 , 22, 23, 24 Frailty has been associated with older adults, dependent status, metabolic syndrome, greater hospitalization rates and intensive care unit admissions, surgical complications and readmissions, and higher mortality.17 , 22 , 23 , 25 Frailty, in addition to comorbidities, has also been associated with severe COVID-19 disease that may prolong recovery and worsen functional decline.26 , 27 The vulnerable physiologic state of frail persons may be a corollary of an aged and weakened immune system that has poor defense mechanisms from pathogens.26 , 27 Accurate measurement and application of frailty may be essential for establishing effective presurgical interventions that can improve surgical outcomes, reduce postoperative complications (eg, delirium and long-term cognitive dysfunction), identify candidates for surgical revision, and decrease mortality.17 , 23 , 28 , 29

Greater than 50 frailty instruments currently exist (Appendix 1); however, research shows lack of clinical standardization necessary to create treatment guidelines or predict surgical outcomes.18 , 30 In a 7-year prospective study by Kapadia and colleagues,17 frailty was used to assess outcomes of acute care surgery in older patients. The analysis included 1045 patients, 65 years or older, who were divided into frail and nonfrail groups. The Emergency General Surgery Frailty Index and the Trauma-Specific Frailty Index were used to measure frailty and its impact on emergency and trauma-specific surgeries. Both indices were based on a 15-variable questionnaire that included patient comorbidities, activities of daily living, nutrition status, and health habits. Hypertension and diabetes were the most common comorbidities among the study population. The analysis of all patients measured by both frailty indices revealed significantly greater risks for the frail group in comparison with nonfrail group for inpatient complications, disposition to rehabilitation or skilled-nursing facilities, and mortality. The secondary outcome of implementation of routine frailty assessment was independently associated with a lower adjusted risk for major complications, and a higher adjusted risk for rehabilitation/skilled-nursing facilities disposition. When analysis of the frail group was stratified by frailty index, results for the trauma and emergency patients independently revealed significantly higher outcomes in complications, disposition, and mortality, and LOS in the intensive care unit and overall hospital LOS.

Frailty measurements have also been used in various types of nonacute surgery. A systematic review conducted by Shaw and colleagues24 focused on frailty and cancer surgery outcomes. This included 71 studies worldwide on older patients who underwent various types of oncologic surgery, most commonly abdominopelvic. The meta-analysis found that frailty increased the likelihood of 30-day mortality, adverse discharge disposition, postoperative complications, long-term mortality, and LOS. Nevertheless, there is still inadequate research about the effects of frailty in cancer surgery, including relationships specific to tumor type, cancer stage, and metastasis, and use of adjunctive therapies.24

The clinical value of frailty in orthopedic surgery is also generally inconclusive; however, it has potential based on the findings of available research.18 A cohort study by Schuijt and colleagues revealed that a higher frailty index was associated with a higher risk of 90-day mortality.31 , 32 Additionally, Bai and colleagues33 published a large systematic review revealing the association of frailty with higher mortality risk in total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. However, Lemos and colleagues18 and Kitamura and colleagues32 conducted reviews, each including more than 80 orthopedic studies, that emphasize major knowledge discrepancies because of the lack of substantial prospective research and homogeneous use of frailty indices.

Prehabilitation in the context of presurgical frailty

As the general demand for surgery continues to rise with the aging population, there is critical need to better qualify frailty and enhance preoperative health of older patients.34 Emerging use of multimodal prehabilitation, incorporating exercise, nutrition, and/or psychosocial components, may potentially improve surgical outcomes in frail patients (see Fig. 3 ).29 , 34, 35, 36 The exercise component may include such activities as walking capacity (eg, 6-minute-walking test), balance and strength exercises, and inspiratory muscle training.34 , 35 Nutrition programs may involve monitoring of dietary intake and weight changes and preoperative carbohydrate loading.34 , 35 The psychosocial portion typically focuses on behavioral management and mental health screening.1 , 34 When used for surgical candidates, prehabilitation has been shown to optimize mind-body fitness to endure the physiologic stress of surgery while also improving various postoperative outcomes.34 , 35

Fig. 3.

Potential factors that contribute to improved surgical outcomes in acute and nonacute surgery.

Prehabilitation also has potential in optimizing the functional capacity of frail persons. Baimas-George and colleagues34 conducted a systematic review comparing five studies about prehabilitation for frail patients undergoing nonacute surgeries. One of two studies measuring mortality showed a remarkably decreased rate within 30-days and 3-month periods. One of two other studies demonstrated a significant improvement in LOS by 3 days, whereas the other study displayed a trend toward reduced LOS. Yet another study found that improvement in the 6-minute-walking test was associated with shorter LOS. Three of the studies demonstrated that preoperative exercise improved physical functionality. However, there was no difference found in the two studies that analyzed postoperative discharge disposition. Despite some evidence of promising results, this systematic review revealed major inconsistencies in frailty assessments and lack of heterogeneity of prehabilitation programs. Therefore, making comparisons between the studies is limited and simply reinforces the need for standardization of prehabilitation.

The preoperative health of frail individuals may be positively impacted by prehabilitation. This is evidenced by Milder and colleagues,35 who performed a systematic review evaluating prehabilitation in frail patients. Two of several studies assessed prehabilitation in patients undergoing oncologic surgical resections. One of these two studies, which included all frail patients, incorporated prehabilitation via incentive deep breathing exercises at a minimum of three times daily along with nutritional supplementation 5 to 14 days preoperatively depending on malnutrition risk. In comparison with the retrospective control group, the prehabilitation group showed significant reduction in 30-day and 3-month mortality by 14% and 28%, respectively. Additionally, severe complications decreased by 26% and the overall complication rate decreased by 33%. The second study included a prospective analysis of exercise and nutritional prehabilitation conducted remotely at home or in a rehabilitation center for a 2-week period. Most of the patients, however, were classified as nonfrail (73.6%). The outcomes for mortality, postoperative complications, and functional recovery revealed no significant differences between the control and interventional groups. Despite design limitations, comparison of both studies may support that surgical prehabilitation has a greater impact for frail patients.

Measuring frailty before elective surgery

It is important to explore how frailty is measured given its correlation with negative surgical outcomes. Multiple reviews have found that no single tool has been identified as a gold standard for gauging frailty.18 , 23 It has been conceptualized by two models: a phenotype, proposed by Fried and colleagues, which describes frailty as a clinical presentation including at least three of the five features of weakness, slow gait speed, low physical activity, exhaustion, and unintentional weight loss; or an accumulation of age-related deficits, described by Rockwood and colleagues, which uses a multidimensional score based on the total of health deficits across various domains (Table 2 ).18 , 19 , 23

Table 2.

| Phenotype Model (Frailty as a Clinical Presentation of ≥3 Features) | Cumulative Deficit Model (Frailty as a Multidimensional Risk State) |

|---|---|

| Weakness | Functional deficits |

| Slow gait speed | Comorbiditiesa |

| Minimal physical activity | Cognitive dysfunction |

| Exhaustion | Psychosocial risk factors |

| Unintended weight loss | Geriatrics syndromesb |

Comorbidities may include diabetes mellitus, angina, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, diminished sensorium, and functionally dependent status.17

Geriatrics syndromes are multifactorial conditions that may include falls, polypharmacy, depression, cognitive impairment, and/or delirium.23

Several instruments assessing frailty have stemmed from these two models (Table 3 ). Based on the multidimensional risk state model, the Frailty Index (FI) developed by Rockwood and colleagues, has been used to calculate a score based on the quantity of deficits, with the severity of frailty determined by the number of deficits rather than the nature of each deficit.19 The FI signifies a continuum of frailty, but the index may be trichotomized to indicate low, intermediate, and high level of frailty.23 However, Obeid and colleagues proposed the modified Frailty Index (mFI), originally consisting of 11 preoperative risk factors (mFI-11); alterative versions later emerged and reduced measurements to five risk factors (mFI-5).18 In a systematic review by Panayi and colleagues,19 most of the studies used the mFI because the patient characteristics are easily determined clinically through medical history and physical examination. Similarly, a review on the orthopedic surgery population by Lemos and colleagues also used the “cumulative deficit” model (eg, mFI) most frequently; however, there was no consensus on defining and evaluating frailty.

Table 3.

| Measurements | Comments | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Tests that Measure Frailty28 | ||

| Fried phenotype | ≥3 of 5 features: muscle weakness, slow gait speed, low level of physical activity, poor endurance/exhaustion, and unintentional weight loss/loss of muscle mass.36 Modified Fried criteria: Fried + cognitive impairment + depressed mood. |

Across studies, frailty based on the Fried phenotype was associated with mortality. |

| Clinical Frailty Scale | 7 levels of frailty based on visual observation combined with a condensed medical record review. | After the Fried phenotype, this was the next most studied instrument per Aucoin et al30; also associated with mortality and with the largest effect size of any instrument. |

| Frailty Index | An index between 0 and 1 equal to the number of deficits present divided by the deficits measured. Denominator ranges from 30–71 from various domains including comorbidities, polypharmacy, physical and cognitive impairments, psychosocial risk factors, and common geriatric syndromes. | |

| Modified Frailty Index | 5, 11, or 19 items. mFI-11: 11 deficits in the domains of functional status, cardiovascular comorbidities, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and reduced sensorium. | mFI-11 was the most frequently used frailty instrument per multiple systematic reviews.18,19,34 |

| Edmonton Frailty Scale | Includes cognitive impairment, dependence in instrumental ADLs, recent burden of illnesses, self-perceived health, depression, weight loss, medication issues, incontinence, inadequate social support, and mobility difficulties. | |

| Emergency General Surgery Frailty Index17 | 15-variable questionnaire including patient comorbidities, activities of daily living, nutrition status, and health attitude. 0 = nonfrail status, 1 = severely frail status, with frailty defined as ≥0.325. | |

| Trauma-Specific Frailty Index17 | 15 variables from the modified Rockwood frailty questionnaire <0.27 = nonfrail, ≥0.27 = frail. | |

| Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, and Loss of Weight (FRAIL) Scale | A 5-point system based on fatigue, mobility, comorbidities, and weight loss.22 | |

| Reported Edmonton Frail Scale-Thai | Gait speed substituted with “In the last 2 wk, were you able to (i) climb one flight of stairs (ii) walk 1 km” | |

| Comprehensive geriatric assessment |

|

|

| Adult spinal deformity frailty index | Based on comorbidities and patient-reported motility, ADL, independence, cognitive function, and mood. | |

| Cervical deformity frailty index | Based on comorbidities (eg, the mFI-11 and the mFI-5) with the addition of emergent admission and anterior/combined surgical approach.21 | Contains components that are specific to metastatic spine disease (less generalizable to other pathologies). |

| Hospital frailty risk score | Based on an ICD-10 code algorithm to identify diagnoses associated with frailty. | |

| Psoas size21 | Measured on preoperative computed tomography psoas muscle index: cross-sectional area of bilateral psoas muscle/height2.37 | Used as a measure of sarcopenia as a proxy for frailty. Between studies, there is variation in how psoas size is calculated and some studies report that the psoas muscle is not representative of total human skeletal muscle mass, and therefore, not representative of whole-body sarcopenia.21,37,38 In the review by Chan et al,21 psoas size was the measure reporting no association with outcomes most commonly. |

| Comprehensive Assessment of Frailty | Fried phenotype without unintentional weight loss, plus balance assessment, albumin, creatinine, brain natriuretic peptide, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, and Clinical Frailty Scale. | |

| Blood Tests That Measure Frailty38 | ||

| FI from routine blood and urine tests39, 40, 41, 42 | White blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, potassium, creatinine, and albumin; and standard physical measures including blood pressure and/or pulse. | |

| Proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α | Elevated levels are associated with frailty and worse outcomes. | |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 | IGF-1 is involved with maintaining muscle mass, assisting with injury recovery, and is a marker of metabolism. Lower levels of IGF-1 are associated with frailty. | |

| Imaging Tests That Measure Frailty | ||

| Computed tomography and ultrasonography38 | Because these tests often are performed preoperatively, they may be used to evaluate surrogate markers of frailty/opportunity to measure muscle mass and osteopenia (when the studies were performed for another purpose). | Although radiologic studies can reveal a change in muscle mass, they provide no information on muscle performance needed to diagnose sarcopenia clinically. |

| Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry38 | Accepted reference values to detect sarcopenia by DXA: 7.26 kg/m2 for men; <5.45 kg/m2 for women. | However, DXA is not routinely performed to assess muscle mass or before surgery. |

| MRI38 | Assessment of sarcopenia with MRI is being evaluated as a prognostic marker in select groups (eg, as a measure of muscle quality, assessing fat-free muscle area in patients with decompensated cirrhosis). | |

| Other Tests Used to Measure Frailty (Physical) | ||

| Gait speed Timed get up and go Handgrip strength Short physical performance battery |

||

| Other Tests Used to Measure Frailty (Functional) | ||

| Katz Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Activities of Daily Living Eastern Cooperative Group Performance States Self-reported mobility assessment28 |

||

Abbreviations: ADLs, activities of daily living; DXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; FI, Frailty Index; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; mFI, modified Frailty Index.

This is not intended to be a complete list.

A high-quality frailty metric should comprise key elements of objectivity, such as the presence or absence of a comorbidity; reproducibility; and generalizability among different pathologies and surgical procedures.21 This is reflected in the designs of mFI-11 and mFI-5, which have easy calculable scoring, and validation among various surgical specialties that enhances clinical practicality.21 Unlike some other frailty instruments (eg, Edmonton Frailty Scale, Geriatric Consult Index), mFI-11 and mFI-5 exclude subjective components (eg, fatigue and mood) that can negatively affect external validity.

In a systematic review by Aucoin and colleagues,30 the Fried phenotype was the most prevalent out of 35 various frailty instruments. The next most prevalent instruments included the Clinical Frailty Scale, a physical measure of frailty (gait speed, timed get up and go, handgrip strength, short physical performance battery); the FI; the Edmonton Frailty Scale; or a measure of function or disability, such as Katz Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Activities of Daily Living, Eastern Cooperative Group Performance States, or self-reported mobility assessment. However, per Aucoin and colleagues,30 the most common approach to assessing frailty was dichotomization of a frailty instrument (frail vs not frail). Other studies categorized frailty into three levels, and fewer studies categorized frailty into four or more levels or as a continuous measure.30 Chan and colleagues22 concluded that in addition to discrepancies between the frailty tools, there was heterogeneity in the methodology and research groups among studies using the same frailty index. Subsequently, results lack generalizability essential for clinical decision making. Therefore, the authors called for future research on frailty that prioritizes design precision and focused patient populations.

Future directions

Evidence shows that frailty increases the risk for surgery while also negatively impacting acute and nonacute surgical outcomes. There is rising public health attention surrounding the development of clinical tools that will advance medical care for vulnerable, older adults.17 , 18 , 27 Identification of superior frailty assessments with routine surveillance and electronic health record implementation will heighten clinical awareness and drive efforts to optimize the perioperative health status of older patients.17 , 18 , 23 Frailty is also associated with higher hospital expenditure and overall health care costs thus incentivizing establishment of cost-effective interventions to treat older adults.18 Furthermore, attaining an accurate understanding of health trajectories in older adults can help clinicians deliver patient-centered care that addresses quality of life and conveys potential high-risk surgical outcomes.23 , 24 Additional research and standardization of multimodal surgical prehabilitation has fundamental potential to improve surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction, minimize postoperative complications, and reduce morbidity and mortality of older adults.31 , 33 , 34

Summary

Precautionary measures and social isolation enforced during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in reduced access to elective surgeries and heightened exposure to physiologically harmful conditions that caused a major decline in baseline health statuses of vulnerable populations. These disadvantaged groups, not mutually exclusive, include individuals with frail syndrome, older age, disability, and racial-ethnic minority status. Furthermore, these patient groups have known associations with higher rates of postoperative complications, hospital readmissions, longer LOS, nonhome discharges, poor patient satisfaction, and mortality. Surgical prehabilitation has potential to improve postoperative outcomes for comorbid, older populations. Frailty is a common measurement used to identify these surgically high-risk individuals. However, future research is required to help standardize frailty tools for clinical application. Optimal measurement tools will improve identification of older, frail patients, and subsequently direct designs for population-specific, multimodal prehabilitation to reduce postoperative risks and mortality.

Clinics care points

-

•

Geriatric syndromes may include falls, polypharmacy, depression, cognitive impairment, and/or delirium.

-

•

Clinical use of comorbidity alone is an inadequate measure of health status because it excludes significant factors, such as functionality, physical endurance, and cognition, which collectively can impact medical management and surgery.

-

•

Frailty may be a valuable predictor of poor outcomes in surgical patients.

-

•

Clinical implementation of an effective frailty tool may be critical for risk stratification and optimal medical management and surgical decision-making.

-

•

Multimodal prehabilitation may reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality for vulnerable, older populations including individuals with comorbidities, frail syndrome, disabilities, or racial-ethnic minority status.

Author disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary data

Frailty measurements used in surgical patients is available online.

References

- 1.Silver J.K., Santa Mina D., Bates A., et al. Physical and psychological health behavior changes during the COVID-19 pandemic that may inform surgical prehabilitation: a narrative review. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2022;12(1):109–124. doi: 10.1007/s40140-022-00520-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shinall M.C., Arya S., Youk A., et al. Association of preoperative patient frailty and operative stress with postoperative mortality. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(1):e194620. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George E.L., Hall D.E., Youk A., et al. Association between patient frailty and postoperative mortality across multiple noncardiac surgical specialties. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):e205152. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afilalo J., Mottillo S., Eisenberg M.J., et al. Addition of frailty and disability to cardiac surgery risk scores identifies elderly patients at high risk of mortality or major morbidity. Circ: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(2):222–228. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim G.U., Park J., Kim H.J., et al. Definitions of unfavorable surgical outcomes and their risk factors based on disability score after spine surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03323-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob K.C., Patel M.R., Collins A.P., et al. The effect of the severity of preoperative disability on patient-reported outcomes and patient satisfaction following minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. World Neurosurgery. 2022;159:e334–e346. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzola P., Bellelli G., Broggini V., et al. Postoperative delirium and pre-fracture disability predict 6-month mortality among the oldest old hip fracture patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0242-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudisill S.S., Varady N.H., Birir A., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in total joint arthroplasty care: a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.08.006. S088354032200746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardinal T., Bonney P.A., Strickland B.A., et al. Disparities in the surgical treatment of adult spine diseases: a systematic review. World Neurosurgery. 2022;158:290–304.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saggu R.K., Barlow P., Butler J., et al. Considerations for multimodal prehabilitation in women with gynaecological cancers: a scoping review using realist principles. BMC Wom Health. 2022;22(1):300. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01882-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang N.Q., Tan Y.X., Samuel M., et al. Multimodal prehabilitation in older adults before major abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2022;407(6):2193–2204. doi: 10.1007/s00423-022-02479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molenaar C.J., van Rooijen S.J., Fokkenrood H.J., et al. Prehabilitation versus no prehabilitation to improve functional capacity, reduce postoperative complications and improve quality of life in colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013259.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillis C., Davies S.J., Carli F., et al. Current landscape of nutrition within prehabilitation oncology research: a scoping review. Front Nutr. 2021;8:644723. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.644723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillis C., Buhler K., Bresee L., et al. Effects of nutritional prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):391–410.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheede-Bergdahl C., Minnella E.M., Carli F. Multi-modal prehabilitation: addressing the why, when, what, how, who and where next? Anaesthesia. 2019;74(Suppl 1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/anae.14505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkins D., Best D., Briss P.A., et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapadia M., Obaid O., Nelson A., et al. Evaluation of frailty assessment compliance in acute care surgery: changing trends, lessons learned. J Surg Res. 2022;270:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemos J.L., Welch J.M., Xiao M., et al. Is frailty associated with adverse outcomes after orthopaedic surgery? A systematic review and assessment of definitions. JBJS Reviews. 2021;9(12) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.21.00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panayi A.C., Orkaby A.R., Sakthivel D., et al. Impact of frailty on outcomes in surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2019;218(2):393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arai Y., Kimura T., Takahashi Y., et al. Preoperative frailty is associated with progression of postoperative cardiac rehabilitation in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;67(11):917–924. doi: 10.1007/s11748-019-01121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan R., Ueno R., Afroz A., et al. Association between frailty and clinical outcomes in surgical patients admitted to intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(2):258–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan V., Wilson J.R.F., Ravinsky R., et al. Frailty adversely affects outcomes of patients undergoing spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine J. 2021;21(6):988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin H.S., McBride R.L., Hubbard R.E. Frailty and anesthesia: risks during and post-surgery. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:61–73. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S142996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw J.F., Budiansky D., Sharif F., et al. The association of frailty with outcomes after cancer surgery: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(8):4690–4704. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-11321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang X., Xu X., Ding L., et al. The association between metabolic syndrome and presence of frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s41999-022-00688-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramaniam A., Shekar K., Afroz A., et al. Frailty and mortality associations in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Med J. 2022;52(5):724–739. doi: 10.1111/imj.15698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wanhella K.J., Fernandez-Patron C. Biomarkers of ageing and frailty may predict COVID-19 severity. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;73:101513. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gracie T.J., Caufield-Noll C., Wang N.Y., et al. The association of preoperative frailty and postoperative delirium: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2021 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tjeertes E.K.M., van Fessem J.M.K., Mattace-Raso F.U.S., et al. Influence of frailty on outcome in older patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging and disease. 2020;11(5):1276. doi: 10.14336/AD.2019.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aucoin S.D., Hao M., Sohi R., et al. Accuracy and feasibility of clinically applied frailty instruments before surgery. Anesthesiology. 2020;133(1):78–95. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuijt H.J., Morin M.L., Allen E., et al. Does the frailty index predict discharge disposition and length of stay at the hospital and rehabilitation facilities? Injury. 2021;52(6):1384–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitamura K., van Hooff M., Jacobs W., et al. Which frailty scales for patients with adult spinal deformity are feasible and adequate? A systematic review. Spine J. 2022;22(7):1191–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai Y., Zhang X.M., Sun X., et al. The association between frailty and mortality among lower limb arthroplasty patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):702. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03369-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baimas-George M., Watson M., Elhage S., et al. Prehabilitation in frail surgical patients: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2020;44(11):3668–3678. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milder D.A., Pillinger N.L., Kam P.C.A. The role of prehabilitation in frail surgical patients: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62(10):1356–1366. doi: 10.1111/aas.13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moskven E., Charest-Morin R., Flexman A.M., et al. The measurements of frailty and their possible application to spinal conditions: a systematic review. Spine J. 2022;22(9):1451–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magnuson A., Sattar S., Nightingale G., et al. A practical guide to geriatric syndromes in older adults with cancer: a focus on falls, cognition, polypharmacy, and depression. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39:e96–e109. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_237641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fried L.P., Tangen C.M., Walston J., et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurumisawa S., Kawahito K. The psoas muscle index as a predictor of long-term survival after cardiac surgery for hemodialysis-dependent patients. J Artif Organs. 2019;22(3):214–221. doi: 10.1007/s10047-019-01108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bentov I., Kaplan S.J., Pham T.N., et al. Frailty assessment: from clinical to radiological tools. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(1):37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howlett S.E., Rockwood M.R.H., Mitnitski A., et al. Standard laboratory tests to identify older adults at increased risk of death. BMC Med. 2014;12:171. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rockwood K., McMillan M., Mitnitski A., et al. A frailty index based on common laboratory tests in comparison with a clinical frailty index for older adults in long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(10):842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blodgett J.M., Theou O., Howlett S.E., et al. A frailty index based on laboratory deficits in community-dwelling men predicted their risk of adverse health outcomes. Age Ageing. 2016;45(4):463–468. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritt M., Jäger J., Ritt J.I., et al. Operationalizing a frailty index using routine blood and urine tests. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1029–1040. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S131987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Frailty measurements used in surgical patients is available online.