Abstract

Characterization and classification of soils is a major tool for understanding the nature and status of soils. The objective of the study was to characterize, classify and map the soils of Upper Hoha sub-watershed according to the World Reference Base for Soil Resources [1]. Seven representative pedons were opened in Upper Hoha sub-watershed at different landscape positions. Accordingly, the surface soils of Pedon 2, 3, and 7 consisted of Mollic horizons; whereas Pedon 1, 4, 5 and 6 had Umbric horizons. The subsurface diagnostic horizons identified for the opened pedons were Nitic, Cambic, Ferralic, Plinthic and Pisoplinthic horizons. Pedon 1, 2, 4, 5 and 7 contained a Nitic horizon; whereas, Pedon 3 and 6 had Cambic horizons. Also Pedon 3, 4 and 6 had Plinthic, Ferralic and Pisoplinthic subsurface horizons respectively. The surface soils of Pedon 1, 2 and 4 showed anthric properties which is affected by long-term plowing; and Pedon 2, 5 and 6 showed sideralic properties in the subsurface soils which had lower CEC <24 cmolc kg−1 clay. Pedon-3 and 7 showed abrupt textural difference in clay content between surface and subsurface horizons; in particular, Pedon-7 had colluvic materials deposition. As a result, soils of Upper Hoha sub-watershed were classified in reference soil groups of Nitisols, Cambisols and Plinthosols with their corresponding qualifiers.

Keywords: Anthric properties, Mollic horizon, Sideralic properties, Umbric horizon, Nitic horizon

1. Introduction

Soil classification helps in understanding the nature, properties, dynamics and functions of the soil as part of landscapes and ecosystems [2]. It is useful to recognize the properties of soil and their distribution over an area in order to develop management plans for efficient utilization of soil resources [3,4]. Detailed information on soil characteristics is required to make decisions with regard to soil management practices for sustainable agricultural production, rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems and sound researches on soil fertility [[5], [6], [7]]. The success of soil fertility management depends mainly on understanding how soils respond to different agricultural practices over time [[8], [9], [10]]. Generally, characterization and classification of agricultural soil is a master key for describing and understanding the fertility status of soils [11,12].

Ethiopia has a wide altitude range from 116 m below sea level to 4620 m above sea level [13]. This diversity in topography, climate and living organisms, as soil forming factors has resulted in different types of soils. Even though soil resources in Ethiopia are considered as a major asset and the country’s economy is largely dependent on agricultural activities; their management is poor and facing many challenges [14]. Severe soil degradation problems in Ethiopia are caused by overexploitation of the soil resources through unwise use of agricultural lands with lack of site specific information on soil and land characteristics. This triggered the removal of billions of tons of soils every year by erosion; and the loss of related functions and services along with the soils [15,16].

Assosa Zone is one of the peripheral areas in Ethiopia where research activities were not adequately conducted relative to the central parts of the country. As a result, watershed-based soil characterization and classification have not yet been intensively done in the Zone. The current widely used soil resource information in the area is the small scale 1:2 million provisional soil map of Ethiopia prepared by FAO [17] as well as the Digital Soil and Terrain (SOTER) database and maps of North-East African countries including Ethiopia which were done in 1:1 million scales by FAO [18]. However, the information is still limited because the previous soil maps focused only on the organic carbon content and base saturation of the soils for classification and is generalized from a few observations scattered over wide areas. Therefore, large scale soil information is very important in Assosa Zone where the previous research activities are insufficient. The objective of this study was to characterize, classify and map the soils of Upper Hoha sub-watershed by using the morphological, physical and chemical properties of the soils with the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) system of classification [1].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study site

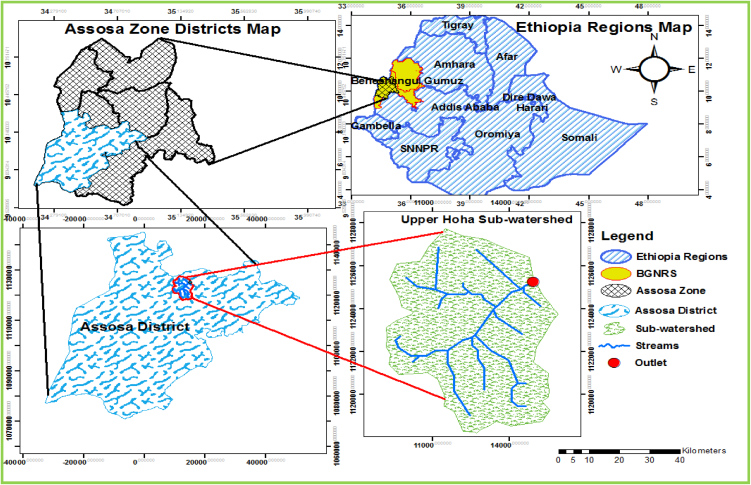

The soil profile characterization study was carried out in Upper Hoha sub-watershed in Assosa District of Assosa Zone in Beneshangul Gumuz National Regional State in Western Ethiopia. Upper Hoha sub-watershed covers: Amba-2, Amba-3, Amba-7, Amba-8, Amba-9, Agusha and Tsetse-adirinunu Rural Kebeles (the smallest administrative units in Ethiopia) of Assosa District. Upper Hoha sub-watershed lies between 10°5′09″ and 10°10′24″N latitude and from 34°31′30″ to 34°35′06″E longitude (Fig. 1). Total area of the sub-watershed is 4346 ha with an altitude range of 1462 m–1580 masl. The number of households that live in the sub-watershed is 1352 [19].

Fig. 1.

Location map of Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

2.2. Climate and topography

Assosa District has two agro-climatic zones; 90% Kolla (lowland below 1500 masl) and 10% Weyna-dega (midland between 1500 m and 2300 masl). According to MoA [20] the agro-ecological zone of Assosa Zone is SH1 (hot to warm sub-humid lowlands). Based on 10 years of climatic data (2008–2017) obtained from Ethiopian Meteorology Agency, Benishangul Gumuz Region Service Center, the mean monthly temperature range of the District is 15–28 °C and the mean annual rainfall is 1183 mm (Fig. 2). The rainfall distribution pattern of Assosa District is mono-modal, which is only one rainy season in the area. The rainy season extends from May to October for a continuous six months whereas the dry season extends from November to April [21]. The topographic condition of Assosa District is plateau, plains, hills and valleys [22].

Fig. 2.

Climatic data of Assosa District.

2.3. Land use and farming system

Like other parts of Ethiopia, agriculture is the main livelihood source for Assosa District. The agricultural system that is widely practiced in the District is mixed crop-animal production. In addition, hunting, wild food collection, traditional gold mining and petty trade are secondary livelihood sources in the District. The major annual crops that are cultivated in the District are sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), maize (Zea mays L.), niger seed (Guizotia abyssinica), sesame (Sesamum aestivum), soya-bean (Glycine max L.), haricot bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and groundnut (Arachis hypogaea). Perennial crops such as mango (Mangifera indica), banana (Musa indica), papaya (Carica papaya), orange (Citrus sinensis) and avocado (Persea americana) are also widely grown [22,23].

2.4. Soils and geology

Western Ethiopia is made up of a range of supra-crustal and plutonic rocks [24]. Specifically, Assosa area soils are made up of Precambrian rocks, Tertiary age groups of volcanic rocks and Quaternary age groups of lacustrine and alluvial deposits [25]. The area is dominated by granite which is massive intrusive igneous rock overlaid by volcanic rocks like scoriaceous basalt of the Tertiary and Quaternary period. The granite rocks have coarse grain texture composed of three major aluminosilicate minerals, quartz (20–30%), feldspar enriched with Albite (sodic plagioclase) (35–40%) and orthoclase (potassic feldspar) (45–60%). In addition to this mica group minerals like biotite and muscovite are the minor minerals that constitute granite rocks of the Assosa area [26]. Based on the FAO [17] major soil type map of Ethiopia, the dominant soil type of the study site is Humic Nitosols.

2.5. The sub-watershed area delineation

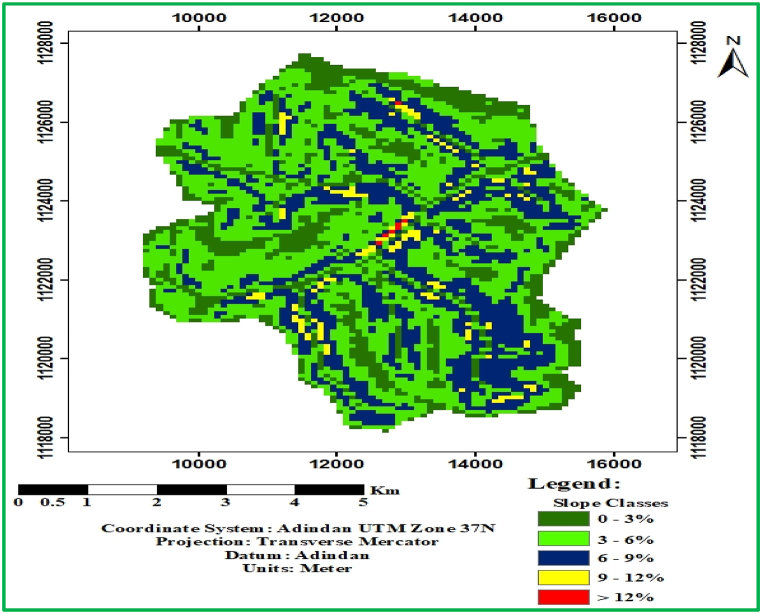

Prior to the research work, the boundary of the sub-watersheds and the rural Kebeles included in the sub-watersheds were identified by using a 1:50,000 scale topographic map of the Assosa District (1034D3) [27] prepared by the Ethiopian Mapping Agency. Then, after taking the outlet coordinates of the sub-watersheds with a GPS device, the catchment area delineation and slope classes analysis were conducted by 30 m × 30 m resolution of a digital elevation model (DEM) using Arc GIS software of version 10.6 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Slope map of Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

2.6. Soil profile description and sampling

A reconnaissance survey was carried out in Upper Hoha sub-watershed to determine representative site for pedon opening. Subsequently, general site information was gathered including: climate condition, topography and landform, location and elevation, land use and major crops, vegetation types, human interference and degradation status, and geology and parent material of the sub-watersheds. A total of seven pedons in Upper Hoha sub-watershed each having a volume of 2 m × 1.5 m × 1.5 m were excavated; after augering 1.2 m depth on 6–8 spots to select the appropriate site for each pit. The soil horizons were described insitu following the FAO [2] Guidelines for Field Soil Description.

The morphological characteristics considered during the characterization and classification of the soils were: thickness of each horizon, horizon boundary, textural class, coarse fragments, mottles, soil structure, color, consistence, moisture status, porosity, coatings, cementation (compaction), mineral concentrations, abundance and size of roots, carbonates content and biological activity. Carbonates content was tested by 10% HCl and soil color was described by using Munsell Soil Color Book [28]. After horizons designation, the soil samples were collected from each horizon for physicochemical properties analysis.

2.7. Field soil survey

After opening the pedons in the catchment, the auger soil samples were collected from 132 spots of the entire area of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed with depths of 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm by zigzag method, and soil properties like: soil texture, depth of surface horizon and color analysis by Munsell Soil Color Book [28] were examined in field and in laboratory to identify the boundary of the soil mapping unit of the soil types defined by the pedons opened [[54]]. A GPS device was used to register the specific location of the auger points.

2.8. Soil sample preparation and laboratory analysis

The collected soil samples were processed and analyzed at Assosa Soil Testing Laboratory and Holeta Agricultural Research Center based on standard laboratory procedures. The soil samples were air-dried and ground to pass through a 2 mm sieve and 0.5 mm sieve (for total N and organic carbon) before analysis as described by Van Reeuwijk [29]. Soil texture was determined by the Bouyoucos hydrometer method [30]. The pH was determined in water (1:2.5 soil: water ratio) by using a pH meter [29]. Organic carbon (OC) content of the soil was determined following the wet combustion method [31]. Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using the wet digestion procedure of the Kjeldhal method [32]. The available phosphorus content of the soil was determined by the Olsen method, extracting with 0.5 M NaHCO3 solution at pH 8.5 [33].

Exchangeable cations (Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+) and cation exchange capacity (CEC) of clay and the soils were determined following the 1 M ammonium acetate (pH 7) method [34]. The exchangeable K+ and Na+ in the extract were measured by flame photometer (CL 378, ELICO, India); whereas Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the leachate were measured using AAS (Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer) (Agilent 200 series AA, Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). Exchangeable acidity of the soil was extracted by leaching exchangeable hydrogen (H+) and aluminum ions (Al3+) from the soil samples by 1 M KCl solution and determined by titrating 25 ml supernatant with 0.02 M NaOH by using 1 g L−1 phenolphthalein as the indicator; Al was determined by back-titration with a solution of 1 M NaF and 0.02 M HCl [35]. Available micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cu) content of the soils was extracted by Diethylene Triamine Pentaacetic Acid (DTPA), triethanolamine (TEA) and calcium chloride; the pH was adjusted to 7.3 and the contents in the extract were determined by AAS [36]. Percentage base saturation (PBS), effective base saturation (EBS) and silt-to-clay ratio were calculated from the obtained laboratory results.

| (1) |

where: PBS= Percentage Base Saturation; CEC = Cation exchange capacity in cmolc kg−1 soil

| (2) |

where: EBS = Effective Base Saturation.

2.9. Soil classification and mapping

The soils were classified according to the World Reference Base for Soil Resources [1] procedures. In addition, the auger points recorded during field soil survey were transferred to Excel spread sheet and later displayed on the sub-watershed delineated by Arc GIS software. Then soil type maps of Upper Hoha sub-watershed were generated by relating the analysis results of soil texture, color and depths of the surface horizon with respective soil types identified for each pedon. The soil type map was created by spatial interpolation using auger points of identified characteristics to estimate unidentified parts of the sub-watershed by considering the closest points to the identified points. Accordingly, the IDW (Inverse Distance Weighted) spatial analysis tool was manipulated to create the soil map.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Site characteristics

The site characteristics of Upper Hoha sub-watershed include differences in landscape positions, erosion levels and land use types (Table 1). There are four landscape positions in the sub-watershed: upper slope, middle slope, lower slope and toe slope. Thus, each landscape position was represented by two pedons, except toe slope, which was represented by one pedon: that is, Pedon-1 and Pedon-2 (upper slope), Pedon-3 and Pedon-4 (middle slope), Pedon-5 and Pedon-6 (lower slope) and Pedon-7 (toe slope). The soils of all sites were found very deep and well drained except for soils of Pedon-3 on the middle slope and Pedon-6 on the lower slope of the sub-watershed which had concretions within 100 cm of the soil depth. In the upper and middle slope classes, there was sheet and rill erosion, whereas gully erosion was observed on the lower slope because of the concentration of flood discharge from the upslope. Consequently, removal of soil particles from upper, middle and lower slope position and deposition on toe slope position of the sub-watershed are common occurrences that contribute to textural class differentiation in the surface soil profile.

Table 1.

Site characteristics of the pedons in Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

| Pedon | Geographical position |

Altitude (asl) | Slope (%) | Topographic position | Local physiography | Parent materials | Land use types | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | |||||||

| 1 | 10°06′14″ | 34°33′54.6″ | 1577 m | 2 | Upper slope | Convex plateau | Residual materials | Niger seed farmland |

| 2 | 10° 07′21.4″ | 34°33′58″ | 1553 m | 3 | Upper slope | Slightly hilly to the east | Weathered basalt rocks | Maize farmland |

| 3 | 10°09′38.3″ | 34° 32′51.9″ | 1550 m | 4 | Middle slope | Gentle slope | Weathered granite rock | Maize farmland |

| 4 | 10°07′47.4″ | 34°32′32.5″ | 1529 m | 2 | Middle slope | Plain, slopping to the south | Residual materials | Sorghum farmland |

| 5 | 10°08′7.9″ | 34°34′30.7″ | 1524 m | 3 | Lower slope | Gentle slope | Residual materials | Finger millet farmland |

| 6 | 10°08′48.6″ | 34°32′25.6″ | 1494 m | 7 | Lower slope | Slopping to river valley | Weathered granite rock | Grazing land |

| 7 | 10 08′44.1″ | 34°34′19.1″ | 1466 m | 1 | Toe slope | Plain, hilly to the east | Colluvic materials | Grazing land |

Scor. basalt = Scoraceous basalt.

3.2. Morphological properties of the soils

The number of genetic or master soil horizons per pedon was two for all sites where the pedons were opened. Pedon-7 which is found on the toe-slope of the sub-watershed had thick surface horizon due to deposition of the eroded soil particles from the upper and middle slopes of the catchment. This agrees with the result of a toposequence study carried out in the Southern part of Ethiopia in Gununo area [37], which confirmed that the pedons opened on a convex plateau (plain with 2% slope) and depression had a deeper and darker surface layer as compared to the undulating upper and middle slope soils; due to low removal of soils by water erosion and continuous deposition of soil material from the upslope catchment.

The surface horizon of Pedon-7 was made from deposition of colluvic materials eroded from the upper part of the sub-watershed. The underlying subsurface horizons of the opened pedons were made from weathering of parent materials like granites and quartz [26]. The plinthic and pisoplinthic subsurface horizons found in Pedon-3 and Pedon-6 have been formed by a redoximorphic process which is repeated wetting and drying of kaolinite and iron oxide rich clay minerals with free access of oxygen [1].

The dry and moist soil color hue of Upper Hoha sub-watershed surface soils varied from 2.5YR to 10YR; whereas the values of dry soils were 3–4 and the moist soils were 2–3. The chromas of dry and moist surface soils were 2–4. The dry and moist subsurface soils color hue varied between 10R and 10 YR; and the value of the dry soils were 3–5 while the moist soils were 2.5–4. The chromas of dry subsurface soils were 4–8; while the moist soils were 3–6. Chroma of dry and moist soils was lower on the surface horizon than on subsurface horizons; this is attributed to the influence of organic matter on the color of surface soils. In addition, the difference in soil color among the pedons might be due to variation in parent material, organic matter content and oxidation-reduction reaction in the soil [38,39].

The soils of all locations under study had a weak to moderate aggregate arrangement. Particularly, the plinthite nodules in Pedon-3 and 6 had weak aggregate arrangements, where the overlying layers had mostly moderate arrangements. The surface horizons had medium size granular structure and the subsurface horizons had medium to coarse sub-angular and angular blocky structures. Soil aggregate size was increased down the profile; this could be due to increase in clay particles down the vertical layers of the soil. The horizon boundaries had clear distinctness at the surface but were gradual and diffuse on the bottom layers along with smooth topography in all horizons of the opened pedons.

The dry consistencies of the soils were slightly hard to very hard. Accordingly, all of the surface soils were hard but the subsurface horizons were slightly hard except the pedons with plinthic horizons which had very hard consistency. The moist consistency of the surface soils was friable; whereas the subsurface horizons were very friable but the plinthite nodules were firm to very firm. The wet consistency of the surface and subsurface soils of all locations were sticky and plastic except the plinthic horizons which were slightly sticky to non sticky and slightly plastic to non-plastic. The abundance and size of plant roots in the surface horizons were few to many and fine to coarse roots respectively, but they decline down the profile and only very few fine roots to none were found at the bottom subsurface horizons (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morphological description of the pedons in Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

| Pedon | Horizon Depth (cm) | Horizon | Horizons Boundary | Soil Color |

Field Textural Classes | Soil Structure (#) | Soil Consistency (*) | Roots ($) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | Moist | ||||||||

| 1 | 0–22 22–53 53–87 87–113 113+ |

Ap A1 Bt1 Bt2 Bt3 |

C,S C,S G,S G,S D,S |

5 YR 4/4 2.5 YR 4/4 2.5 YR 4/6 5 YR 4/6 2.5 YR 4/8 |

5 YR 2.5/2 2.5 YR 3/4 2.5 YR 3/6 5 YR 3/4 2.5 YR 3/6 |

CL C C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB MO,ME,AB MO,CO,AB WE,CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL HA,FR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL |

Me,Ma Fi,Cm Fi,Fe VF,V VF,V |

| 2 | 0–32 32–57 57–93 93–124 124+ |

Ap Bt1 Bt2 Bt3 Bt4 |

C,S C,S C,S G,S G,S |

5 YR 4/2 5 YR 4/4 5 YR 4/6 5 YR 4/6 5 YR 3/4 |

5 YR 2.5/2 5 YR 3/4 7.5 YR 4/6 5 YR 3/4 5 YR 4/6 |

C C C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB MO,ME,AB MO,CO,AB WE,CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL HA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL |

Cr,Fe Me,Cm Fi,Fe VF,V VF,V |

| 3 | 0–25 25–49 49–90 90–124 124+ |

Ahp AB B1 Bc1 Bc2 |

C,S C,S C,S G,S G,S |

5 YR 3/3 2.5 YR 3/4 2.5YR3/4 2.5 YR 3/6 2.5YR3/6 |

5 YR 2.5/2 2.5 YR 3/3 2.5 YR 2.5/4 2.5 YR 2.5/4 2.5 YR 3/4 |

SiCL C C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB MO,ME,SAB WE,CO,AB WE, CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL HA,FR,ST,PL SHA,FR,ST,PL HA,FI,SST,SPL VHA,FI,SST,SPL |

Cr,Fe Me,Cm Fi,Fe Fi,Fe N |

| 4 | 0–20 20–52 52–81 81–117 117+ |

Ap A1 A2 Bt1 Bt2 |

C,S C,S G,S D,S D,S |

5 YR 4/4 2.5 YR 3/6 2.5 YR 4/6 2.5 YR 3/6 2.5 YR 3/6 |

5 YR 3/3 2.5 YR 2.5/4 2.5 YR 3/4 2.5 YR 3/4 2.5 YR 3/4 |

CL C C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB SR,ME,AB MO,CO,AB WE,CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL HA,FR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL |

Me,Ma Me,Ma Fi,Cm Fi,Fe VF,Fe |

| 5 | 0–30 30–65 65–85 85–112 112+ |

A Bt1 Bt1 Bt3 BC |

C,S C,S G,S D,S D,S |

2.5 YR 4/4 2.5 YR 4/6 10R 4/6 2.5 YR 4/8 2.5 YR 3/6 |

2.5 YR 2.5/4 2.5 YR 3/6 10R 3/4 2.5 YR 4/4 2.5 YR 3/4 |

C C C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB MO,CO,SAB MO,CO,AB WE,CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL SHA,FR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL |

Cr,Fe Me,Cm Cm,Fe Fi,Fe Fi,V |

| 6 | 0–23 23–38 38–86 86+ |

A AB Bc1 Bc2 |

C,S C,S G,S G,S |

5 YR 3/3 5 YR 4/4 2.5 YR 4/6 2.5 YR 4/6 |

5 YR 3/2 5 YR 3/4 2.5 YR 3/4 2.5 YR 3/6 |

CL C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB MO,CO,SAB WE,CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL SHA,FR,ST,PL SHA, FR,SST,SPL VHA,FR,NST,NPL |

Cr,Fe Fi,Ma Fi,Fe Fi,V |

| 7 | 0–31 31–50 50–81 81–124 124+ |

Ah1 Ah2 AB Bt1 Bt2 |

C,S C,S G,S G,S D,S |

10 YR 3/2 5 YR 4/4 5 YR 4/4 10 YR 4/6 10 YR 5/6 |

10 YR 2/2 5 YR 3/3 5 YR 3/3 10 YR 3/6 10 YR 4/6 |

SiCL C C C C |

MO,ME,GR MO,ME,SAB MO,ME,SAB MO,CO,AB MO,CO,AB |

HA,FR,ST,PL SHA,FR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL SHA,VFR,ST,PL |

Cr,Fe Me,Cm Fi,Fe Fi,Fe Fi,V |

C=Clear; G = Gradual; D = Diffuse; S=Smooth; SiCL=Silty Clay Loam; CL=Clay Loam; C=Clay; Grade: #WE=Weak; #MO = Moderate; SR= Strong; Size: #ME = Medium; #CO=Coarse; Type: #GR = Granular; #SAB=Subangular blocky; #AB = Angular blocky; Dry: *SHA=Slightly hard; *HA=Hard; *VHA=Very hard; Moist: *VFR=Very friable; *FR=Friable; *FI=Firm; *VFR =Very firm; Type: *NST; Non-sticky; *SST=Slightly sticky; *ST=Sticky; *NPL=Non-plastic; *SPL=Slightly plastic; *PL=Plastic; Size: $VF=Very fine; $Fi = Fine; $Me = Medium; $Cr=Coarse; Abundance: $N= None; $V=Very few; $Fe=Few; $Cm=Common; $Ma = Many.

3.3. Physicochemical properties of the soils

In all parts of the sub-watershed clay fraction was the dominant soil particle size class except surface layers of Pedon-3 and Pedon-7 which had higher silt fraction. The clay particles were higher in subsurface horizons than in the surface horizons which might be because of illuviation of clay particles to the underlying horizons or in-situ pedogenetic formation of clay particles by intense weathering in the subsurface horizons [1]. The silt to clay ratios were declining down the profile in all locations of the sub-watershed (0.72–0.08) and as a result they are clayey in texture; which indicates that the soils of the sub-watershed are under advanced weathering stage (Table 3).

Table 3.

Soil texture, pH, OC and TN of the pedons in Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

| Pedon | Depth | Particle size distribution (%) |

Textural class | pH-H2O (1:2.5) | OC (%) | TN (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Silt | Clay | Silt/Clay | ||||||

| 1 | 0–22 | 14 | 36 | 50 | 0.72 | C | 5.3 | 3.08 | 0.15 |

| 22–53 | 16 | 14 | 70 | 0.20 | C | 5.3 | 0.89 | 0.07 | |

| 53–87 | 16 | 14 | 70 | 0.20 | C | 5.3 | 0.46 | 0.07 | |

| 87–113 | 18 | 12 | 70 | 0.17 | C | 5.0 | 0.70 | 0.07 | |

| 113+ | 14 | 6 | 80 | 0.08 | C | 4.8 | 0.58 | 0.07 | |

| 2 | 0–32 | 18 | 28 | 54 | 0.52 | C | 6.2 | 3.24 | 0.20 |

| 32–57 | 14 | 16 | 70 | 0.23 | C | 6.1 | 0.70 | 0.06 | |

| 57–93 | 18 | 16 | 66 | 0.24 | C | 6.1 | 0.85 | 0.07 | |

| 93–124 | 14 | 14 | 72 | 0.19 | C | 6.0 | 0.43 | 0.05 | |

| 124+ | 14 | 14 | 72 | 0.19 | C | 5.9 | 0.39 | 0.06 | |

| 3 | 0–25 | 24 | 42 | 34 | 1.24 | CL | 6.1 | 4.74 | 0.24 |

| 25–49 | 14 | 20 | 66 | 0.30 | C | 5.3 | 2.20 | 0.10 | |

| 49–90 | 10 | 18 | 72 | 0.25 | C | 5.4 | 1.23 | 0.07 | |

| 90–124 | 12 | 21 | 67 | 0.31 | C | 4.7 | 0.92 | 0.06 | |

| 124+ | 14 | 22 | 64 | 0.34 | C | 4.8 | 0.72 | 0.05 | |

| 4 | 0–20 | 20 | 26 | 54 | 0.48 | C | 5.5 | 2.55 | 0.14 |

| 20–52 | 10 | 20 | 70 | 0.29 | C | 5.5 | 1.65 | 0.08 | |

| 52–81 | 6 | 18 | 76 | 0.24 | C | 5.6 | 1.00 | 0.04 | |

| 81–117 | 2 | 18 | 80 | 0.23 | C | 5.6 | 0.84 | 0.04 | |

| 117+ | 6 | 18 | 76 | 0.24 | C | 5.3 | 0.84 | 0.04 | |

|

5 |

0–30 | 16 | 18 | 66 | 0.27 | C | 5.0 | 2.06 | 0.14 |

| 30–65 | 14 | 12 | 74 | 0.16 | C | 4.8 | 0.43 | 0.06 | |

| 65–85 | 14 | 12 | 74 | 0.16 | C | 4.3 | 0.19 | 0.05 | |

| 85–112 | 14 | 14 | 72 | 0.19 | C | 4.4 | 0.43 | 0.04 | |

| 112+ | 14 | 12 | 74 | 0.16 | C | 4.2 | 0.27 | 0.04 | |

| 6 | 0–23 | 22 | 30 | 48 | 0.63 | C | 5.5 | 3.92 | 0.17 |

| 23–38 | 16 | 18 | 66 | 0.27 | C | 5.0 | 2.00 | 0.10 | |

| 38–86 | 12 | 20 | 68 | 0.26 | C | 5.3 | 0.92 | 0.06 | |

| 86+ | 18 | 26 | 56 | 0.46 | C | 5.5 | 0.84 | 0.03 | |

| 7 | 0–31 | 28 | 42 | 30 | 1.4 | CL | 6.2 | 4.90 | 0.19 |

| 31–50 | 14 | 14 | 72 | 0.19 | C | 6.0 | 3.00 | 0.12 | |

| 50–81 | 10 | 24 | 66 | 0.36 | C | 5.3 | 1.56 | 0.09 | |

| 81–124 | 8 | 22 | 70 | 0.31 | C | 5.2 | 1.40 | 0.05 | |

| 124+ | 8 | 20 | 72 | 0.28 | C | 5.3 | 0.80 | 0.04 | |

C = clay, CL = clay loam, OC = organic carbon, TN = total nitrogen.

Based on Havlin et al. [40] the pH values of surface soils ranged from slightly acidic to very strongly acidic (5.0–6.2), whereas, the subsoil’s values were slightly acidic to extremely acidic (4.2–6.1) (Table 3). The Upper Hoha sub-watershed has a subsoil acidity problem which is widespread and its amelioration is costly and often practically infeasible. Similarly, the study conducted in Western Ethiopia in Bedelle District revealed that their surface and sub-surface soils were moderately to extremely acidic [41]. Generally, the soils of Upper Hoha sub-watershed were acidic; particularly, soils of Pedon-1 and Pedon-5 which were more acidic than the rest. This might be due to high annual rainfall of the area up to 1200 mm [21] that could leach down the cations in the soil. The studies conducted in humid regions have revealed that soils become acidic due to leaching of basic cations by high rainfall of the area [12,16].

Furthermore, the variation in pH values among Pedons could be the effect of local physiographic conditions of each site within the sub-watershed which exposed the cations for leaching as well as different anthropogenic activities that enhance acid formation (Table 1). The anthropogenic factors are intensive cultivation that enhances soil cation mining and continuous application of nitrogenous fertilizers that increase soil acidity [42]. Generally, the study result indicates that there is a need for lime application to raise the soil pH to the optimal levels (6.5–7.5) for robust crop production. This helps to minimize nutrient imbalances, toxicity and unavailability of nutrients to plant roots.

According to Landon [43] organic carbon (OC) contents of the surface soils were low <4% except Pedon-3 and Pedon-7 which had a medium level (4–10%); also the subsurface soils of all pedons had a low level of OC (Table 3). This is due to higher plant biomasses on the surface layers than on the subsurface layers, except in Pedon-7, which had better OC up to the 3rd horizon because the soil was formed from colluvic material containing organic matter. The surface and subsurface soils of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed had low total nitrogen (TN) concentration except surface soils of Pedon-2 and Pedon-3 which had medium concentration (0.2–0.5%) according to Landon [43] soil nutrients rating. Similarly, the study conducted in Western Ethiopia in Didessa District revealed that OC contents of surface and subsurface soils were low, while the TN concentration were in medium range at the surface soils and low in subsurface soils; with a decreasing trend down the profile [41]. The difference in TN concentration between the two sites might be due to different fertilizer management practices used over the fields.

The available phosphorus (P) contents of surface and subsurface soils of all locations in the sub-watershed were low (<5 mg kg−1) according to Landon [43]. The result agrees with the finding of research conducted in West Gojam Zone in Mecha and Bure Districts in Northwestern Ethiopia; which revealed low available P in surface and subsurface soils [44]. Basically, the surface horizons of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed had somewhat better concentration of available P than the subsurface horizons. This might be due to the recycling of P in the organic matter by soil microorganisms; and relatively higher tendency of P to be adsorbed on colloidal surfaces to form insoluble complexes with divalent and trivalent cations in the acidic subsurface horizons [45]. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the surface soils ranged between 24.5 and 31.3 cmolc kg−1 soil, which is from medium to high level based on Landon [43]. But the sub-surface soils had low to medium level (9.5–24.0 cmolc kg−1 soil) (Table 4). In both layers Pedon-1 which was opened on the upper slope of the sub-watershed had the smallest value of CEC, whereas Pedon-7, which was opened on the toe-slope of the catchment had the highest value. This might be due to high weathering of clay particles which forms low activity clay such as kaolinite and sesquioxides with low CEC at the upper parts of the catchment. In addition, the CEC of clay ranges 30–38 cmolc kg−1clay in surface horizon, and 16–31 cmolc kg−1 clay in subsurface horizons. Even though the clay particle concentration increases down the profile, the CEC of clay had a decreasing trend down the profile for all the pedons opened in the sub-watershed. This might be due to high concentration of low activity clay minerals with low CEC in the subsurface horizons relative to the surface horizon. CEC of clay in Upper Hoha sub-watershed is low relative to the other parts of the country [39,46].

Table 4.

Av-P, Exchangeable cations, CEC and PBS of the pedons in Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

| Pedon | Depth | Av-P (mg kg−1) | Exchangeable cations and CEC (cmolc kg−1 soil) |

PBS (%) | EBS (%) | PBS: EBS (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | CEC of soil | CEC of clay | ||||||

| 1 | 0–22 | 1.9 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 8.3 | 3.2 | 24.5 | 38 | 49 | 92 | 53 |

| 22–53 | 1.6 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 13.5 | 24 | 65 | 93 | 70 | |

| 53–87 | 1.6 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 12.5 | 26 | 66 | 90 | 73 | |

| 87–113 | 1.6 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 14.5 | 22 | 38 | 66 | 57 | |

| 113+ | 1.6 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 9.5 | 17 | 48 | 60 | 80 | |

| 2 | 0–32 | 1.7 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 9.1 | 4.5 | 27.5 | 38 | 52 | 96 | 54 |

| 32–57 | 1.8 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 8.1 | 3.2 | 20.5 | 27 | 56 | 97 | 58 | |

| 57–93 | 1.6 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 18.6 | 21 | 51 | 98 | 52 | |

| 93–124 | 1.6 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 18.5 | 20 | 39 | 98 | 40 | |

| 124+ | 1.6 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 14.5 | 18 | 41 | 96 | 43 | |

| 3 | 0–25 | 1.9 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 8.8 | 3.7 | 25.3 | 30 | 51 | 97 | 53 |

| 25–49 | 1.8 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 21.5 | 27 | 44 | 91 | 48 | |

| 49–90 | 1.6 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 18.0 | 25 | 42 | 93 | 45 | |

| 90–124 | 1.6 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 18.0 | 20 | 35 | 90 | 39 | |

| 124+ | 1.7 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 15.1 | 18 | 33 | 93 | 36 | |

| 4 | 0–20 | 1.6 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 8.3 | 3.0 | 25.0 | 34 | 47 | 98 | 48 |

| 20–52 | 1.5 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 6.5 | 1.9 | 21.2 | 28 | 41 | 95 | 44 | |

| 52–81 | 1.6 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 5.3 | 2.1 | 18.8 | 24 | 41 | 71 | 58 | |

| 81–117 | 1.6 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 7.0 | 3.5 | 17.7 | 22 | 61 | 81 | 75 | |

| 117+ | 1.8 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 15.4 | 20 | 40 | 60 | 66 | |

| 5 | 0–30 | 1.6 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 26.5 | 36 | 41 | 91 | 45 |

| 30–65 | 1.6 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 20.5 | 28 | 36 | 87 | 42 | |

| 65–85 | 1.5 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 15.9 | 22 | 32 | 60 | 52 | |

| 85–112 | 1.5 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 14.4 | 21 | 42 | 63 | 66 | |

| 112+ | 1.6 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 19.9 | 22 | 28 | 64 | 44 | |

| 6 | 0–23 | 1.6 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 28.9 | 32 | 38 | 94 | 40 |

| 23–38 | 1.6 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 20.8 | 23 | 40 | 70 | 58 | |

| 38–86 | 1.5 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 4.8 | 1.9 | 17.4 | 19 | 41 | 92 | 44 | |

| 86+ | 1.7 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 12.1 | 16 | 41 | 93 | 45 | |

| 7 | 0–31 | 1.6 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 9.7 | 5.3 | 31.3 | 36 | 50 | 97 | 52 |

| 31–50 | 1.5 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 24.0 | 31 | 38 | 94 | 40 | |

| 50–81 | 1.5 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 21.9 | 28 | 43 | 90 | 48 | |

| 81–124 | 1.5 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 22.6 | 30 | 42 | 77 | 55 | |

| 124+ | 1.5 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 6.6 | 4.2 | 21.4 | 26 | 52 | 98 | 53 | |

Av-P = available phosphorus, CEC = cation exchange capacity, PBS = percentage base saturation.

EBS = effective base saturation.

From the exchangeable cations, Ca2+ and Mg2+ took the dominance in the exchange sites of the colloidal complexes of Upper Hoha sub-watershed soils. The surface horizons of the catchment had moderate concentration of Ca2+ (7.1–9.7 cmolc kg−1 soil), but the subsurface soils had a low to moderate range (2.9–8.1 cmolc kg−1 soil) according to Hazelton and Murphy [47]. The exchangeable Mg2+ was high (3.0–5.3 cmolc kg−1 soil) in surface soils (Table 4) but the subsurface soils had a low to high range (0.3–4.6 cmolc kg−1 soil) of exchangeable Mg+2 according to Hazelton and Murphy [47] soil nutrients rating. In Pedon-4 and Pedon-6, the exchangeable Mg2+ concentrations were higher in the subsurface horizons than in the surface horizon; this could be due to the parent material difference between the surface and subsurface layers. The result agrees with the research finding of Daniel and Tefera [48] conducted in the Aba-Midan sub-watershed in Bambasi District in Western Ethiopia; which revealed the soils had low to moderate exchangeable Ca2+ and moderate to high exchangeable Mg+2 in surface and subsurface soils.

Exchangeable Na+ concentration was low in the surface soils of Upper Hoha sub-watershed except Pedon-1 (0.31 cmolc kg−1 soil) and Pedon-7 (0.46 cmolc kg−1 soil) which had moderate level of this nutrient (Table 4). However, in the subsurface horizon Na+ concentration was from very low to low (0.07–0.28 cmolc kg−1 soil). Likewise, exchangeable K+ was low in the surface horizon except Pedon-2 and Pedon-7 which had moderate levels of K+ nutrient. But in the subsurface soils, the K+ concentration was very low to low (0.1–0.26 cmolc kg−1 soil) based on the Hazelton and Murphy [47] soil nutrients rating.

Percentage base saturation (PBS) of the surface soils was in the medium range at all sites where the pedons were opened except Pedon-6 which had low base saturation (Table 4). However, the subsurface horizons had low to high concentrations of base saturation (28–66%) based on Hazelton and Murphy [47] soil nutrients rating. This might be because the parent materials from which the subsurface soils of the study area were made were mostly felsic rocks (acidic rocks) like granite and quartz, orthoclase, albite and muscovite minerals according to Natnael [26]; these conditions lead the base saturation in the soil profile to be relatively low.

Exchangeable acidity concentrations of Upper Hoha sub-watershed ranged from 0.24 to 1.60 cmolc kg−1 soil on the surface horizon but in the subsurface horizons greatly increased with a range of 0.26–5.04 cmolc kg−1 soil; in particular, Pedon-1, Pedon-4, Pedon-5 and Pedon-7 had higher exchangeable acidity mainly Al+3 in the subsurface soils. This might be due to lower soil pH in the subsurface soils which enhanced the solubility of Al3+.

From the available micronutrients, Fe and Mn were dominant in soils of the study area (Table 5). The surface soils had very high (31.5–95.1 mg kg−1 soil) concentrations of available Fe, whereas the subsurface soils had low to very high (8.2–34.9 mg kg−1 soil) available Fe concentrations according to Barrett et al. [49]. In line with this finding, Pedon-1, Pedon-2 and Pedon-3 had higher available Fe concentrations in surface soils than did the other pedons (Table 5). This could be due to the parent materials from which the surface soils were made like ferromagnesian minerals (Pyroxene, Olivine, Biotite and Amphibole) in basaltic rock would contribute to the formation of high Fe in the soils. But the subsurface soils of upper Hoha sub-watershed were made from granite rocks composed of aluminosilicate minerals like quartz, feldspar and mica (muscovite) [26]. Similarly, available Mn was in the range of high to very high (25.0–199.8 mg kg−1 soil) concentrations in the surface horizon, and very low to high (1.9–17.4 mg kg−1 soil) in the subsurface soils according to Barrett et al. [49]. The difference in Mn nutrient concentration between surface and subsurface soils might be explained by different parent materials from which the soils were made. Relatively higher organic matter mineralization processes in the surface soils might also contribute to the greater abundance of Mn nutrient in the surface soils than in the subsurface soils. The result agrees with the research finding of Alemayehu [41] conducted in Didessa District of Western Ethiopia; which revealed very high available Fe and Mn concentrations in surface soils.

Table 5.

Exchangeable acidity and micronutrients of the pedons in Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

| Pedon | Depth | Exchangeable acidity (cmolc kg−1 soil) |

Micronutrients (mg kg−1 soil) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al3+ | H+ | Ex. Acidity | Fe | Mn | Cu | Zn | ||

| 1 | 0–22 | 1.04 | 0.16 | 1.20 | 78.6 | 139.9 | 3.0 | 0.1 |

| 22–53 | 0.64 | 0.40 | 1.04 | 26.9 | 15.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| 53–87 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 1.04 | 34.0 | 8.6 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| 87–113 | 2.80 | 0.24 | 3.04 | 23.9 | 7.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| 113+ | 3.04 | 0.32 | 3.36 | 16.2 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 2 | 0–32 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 95.1 | 199.8 | 4.6 | 0.4 |

| 32–57 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 26.7 | 13.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |

| 57–93 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 15.0 | 17.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | |

| 93–124 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 16.8 | 9.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| 124+ | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 12.1 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 3 | 0–25 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 78.5 | 109.7 | 3.4 | 1.2 |

| 25–49 | 0.94 | 1.12 | 2.06 | 24.8 | 14.5 | 1.4 | 0.2 | |

| 49–90 | 0.57 | 0.19 | 0.76 | 17.2 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 90–124 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 1.32 | 12.8 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 124+ | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.54 | 9.5 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| 4 | 0–20 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 31.5 | 34.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 20–52 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 19.5 | 9.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | |

| 52–81 | 3.20 | 0.60 | 3.80 | 14.2 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 81–117 | 2.50 | 1.14 | 3.64 | 13.3 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 117+ | 4.00 | 1.04 | 5.04 | 12.7 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| 5 | 0–30 | 1.04 | 0.40 | 1.44 | 50.9 | 107.4 | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| 30–65 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 1.20 | 18.9 | 9.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 65–85 | 3.28 | 0.48 | 3.76 | 14.5 | 5.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 85–112 | 3.52 | 0.32 | 3.84 | 19.2 | 7.8 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| 112+ | 3.20 | 0.64 | 3.84 | 15.0 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 6 | 0–23 | 0.70 | 0.9 | 1.60 | 65.2 | 63.9 | 3.5 | 0.4 |

| 23–38 | 3.60 | 0.8 | 4.40 | 25.7 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | |

| 38–86 | 0.60 | 0.5 | 1.10 | 16.4 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| 86+ | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.94 | 34.9 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 7 | 0–31 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 1.15 | 56.3 | 25.0 | 3.6 | 0.4 |

| 31–50 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 29.4 | 7.7 | 1.0 | 0.2 | |

| 50–81 | 1.10 | 0.10 | 1.20 | 23.4 | 7.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| 81–124 | 2.90 | 0.40 | 3.30 | 23.8 | 6.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | |

| 124+ | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 8.2 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

Ex. Acidity = exchangeable acidity.

Available Cu was high to very high in the surface horizons of the opened Pedons (1.6–4.6 mg kg−1 soil); whereas subsurface horizons were very low to high (0.1–1.4 mg kg−1 soil) according to Barrett et al. [49] (Table 5). Pedon-2, Pedon-6 and Pedon-7 had higher available Cu in the surface soils than did the other pedons. Available Zn concentration in the surface horizons was very low to medium (0.1–1.2 mg kg−1 soil); whereas, subsurface horizons had very low (0.1–0.3 mg kg−1 soil) concentrations of available Zn (Table 5) according to Barrett et al. [49]. The possible reasons for higher Cu and Zn content in surface soils over the subsurface soils might be due to plant roots mining of micronutrients from deeper horizons and accumulating them in the top-soils; also, organic acids are effective complexing agents and enhance the solubility of metallic micronutrients in the topsoils. In addition, the concentration difference of Cu and Zn between the pedons might be due to variations of rocks and minerals from which the soils were made, as well as organic matter content differences among the soils that would mineralize to give available Cu and Zn nutrients.

3.4. Soil classification and mapping

3.4.1. Surface diagnostic horizons, properties and materials

According to IUSS Working Group WRB [1]; Umbric and Mollic horizons are surface diagnostic horizons consisting of mineral materials that are relatively thick (≥20 cm) with: a moderate to high content of organic matter (>0.6%), a dark colored Munsell color value of ≤3 in moist state, and ≤5 in dry state, and a chroma of ≤3 in moist state. However, Umbric horizon has a base saturation by 1 M NH4OAc, pH 7 of <50% on a weighted average throughout the entire thickness of the horizon, whereas; Mollic horizon has a base saturation of ≥50% throughout the entire thickness of the horizon. In addition, Umbric horizon has a lesser grade of soil structure and has mostly pHwater < 5.5, but Mollic horizon has a well-developed structure (usually a granular or fine sub-angular blocky structure); and has high base saturation and pHwater > 6. Accordingly, the surface soils (1st horizon) of Pedon-1, Pedon-4, Pedon-5 and Pedon-6 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Umbric horizon; whereas, surface horizon of Pedon-2, Pedon-3, and Pedon-7 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Mollic horizon (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of soil classification of Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

| Pedons | Diagnostic Horizons |

Diagnostic properties | Diagnostic materials | Soil Type | Area |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface | Sub-surface | ||||||

| Hectare | % | ||||||

| Pedon-1 | Umbric | Nitic | Anthric Siderallic |

– | Hypereutric Anthroumbric Rhodic Nitisols (Aric) | 970 | 22 |

| Pedon-2 | Mollic | Nitic | Anthric | – | Hypereutric Anthromollic Sideralic Nitisols (Aric) | 499 | 12 |

| Pedon-3 | Mollic | Cambic Plinthic |

Abrupt textural difference | – | Hypereutric Rhodic Plinthic Cambisols (Geoabruptic, Clayic, Aric, Humic) | 667 | 15 |

| Pedon-4 | Umbric | Nitic Ferralic |

Anthric | – | Hypereutric Anthroumbric Rhodic Ferralic Nitisols (Aric, Humic) | 964 | 22 |

| Pedon-5 | Umbric | Nitic | – | – | Orthoeutric Umbric Rhodic Sideralic Nitisols | 338 | 8 |

| Pedon-6 | Umbric | Cambic Pisoplinthic |

Siderallic | Umbric Pisoplinthic Plinthosols (Clayic, Hypereutric) | 513 | 12 | |

| Pedon-7 | Mollic | Nitic | – | Colluvic material | Hypereutric Mollic Nitisols (Colluvic, Profundihumic) | 395 | 9 |

Anthric properties show evidence of human disturbance by abrupt lower boundary at plowing depth and evidence of mixing of humus-richer and humus-poorer soil materials by cultivation. Soil with anthric properties has a dark color and a complete absence of traces of soil microorganism activity; these are the two main criteria for recognition and apply to some cultivated soils with mollic or umbric horizons. The surface soils (1st horizon) of Pedon-1, Pedon-2 and Pedon-4 had Anthric properties (Table 6).

Colluvic material is a heterogeneous mixture of soil material that has been transported as a result of erosional wash or soil creep. It is found on slopes, foot-slopes, fans or similar relief positions. It shows evidence of down-slope movement. Based on the study result the 1st horizon of Pedon-7 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Colluvic material.

3.4.2. Sub-surface diagnostic horizons and properties

Nitic horizon is a clay-rich subsurface diagnostic horizon ≥30% clay, and a silt-to-clay ratio <0.4. It has moderately to strongly developed blocky structure breaking to polyhedral, flat-edged or nutty elements with many shiny soil aggregate faces in moist state which is probably the result of alternate micro-swelling and shrinking that produces well-defined structural elements with strong shiny pressure faces [50]. It has <20% difference in clay content over 15 cm to layers directly above and below. The horizon does not form part of a plinthic horizon and has a thickness of ≥30 cm. The difference in clay content with the overlying and underlying horizons is gradual or diffuse. Similarly, there is no abrupt color difference with the horizons directly above and below. The colors are of low value with hues often 2.5YR in moist state, but sometimes redder or yellower. It has intermediate CEC and; the sum of exchangeable bases plus exchangeable Al is about half of the CEC. The subsurface soils of Upper Hoha sub-watershed that fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Nitic horizon are the 2nd and 3rd horizons of Pedon-1; the 3rd and 4th horizons of Pedon-2; the 2nd, 3rd and 4th horizons of Pedon-4; the 2nd horizon of Pedon-5 and; the 2nd and 3rd horizons of Pedon-7 (Table 6).

Cambic horizon is a subsurface horizon showing evidence of pedogenetic alteration that ranges from weak to relatively strong. It has a Munsell color hue of ≥2.5 units redder in moist state than the overlying horizon and a chroma of ≥1 unit higher in moist state than the overlying horizon. It had no rock structure, higher clay particles than the underlying horizon, and thickness ≥15 cm. The main soil forming process responsible for the formation of Cambic horizon is in-situ alteration of the parent materials [51]. Accordingly, the subsurface soils of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed that fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Cambic horizons are the 2nd and 3rd horizons of Pedon-3, and the 3rd horizon of Pedon-6 (Table 6).

Plinthic horizon is a subsurface horizon that is rich in Fe and in some cases also Mn, but poor in humus. It has kaolinitic clay and gibbsite; it usually changes irreversibly to a layer of hard concretions or nodules or a hardpan on exposure to repeated wetting and drying with free access to oxygen. It has ≥15% discrete concretions, organic carbon <1%, stronger Munsell color chroma than the overlying horizons and thickness ≥15 cm. Based on IUSS Working Group WRB [1], the 4th and 5th horizons of Pedon-3 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Plinthic horizon, which was formed by a redoximorphic process of alternate oxidation and reduction reaction in a soil [38].

Pisoplinthic horizon contains concretions or nodules that are strongly cemented to indurated with Fe and in some cases also with Mn oxides. It has ≥40% of the volume occupied by strongly cemented to indurated, yellowish, reddish and/or blackish concretions and/or nodules with a diameter of ≥2 mm. The horizon has a thickness of ≥15 cm and does not form part of a petroplinthic horizon. The 4th horizon of Pedon-6 fulfilled the requirements of Pisoplinthic diagnostic subsurface horizon (Table 6).

Ferralic horizon is a subsurface horizon resulting from long and intense weathering. The clay fraction is dominated by low activity clays and contains various amounts of resistant minerals such as (hydr-) oxides of Fe, Al, Mn and titanium (Ti). It has a CEC (by 1 M NH4OAc, pH 7) of <16 cmolc kg−1 clay. It has a thickness of ≥30 cm, is rich in Fe oxides and usually has a friable consistence. Accordingly, the 5th horizon of Pedon-4 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Ferralic horizon (Table 6).

Sideralic properties refer to mineral soil material that has a relatively low CEC. This occurs in a subsurface layer when CEC (by 1M NH4OAc, pH 7) is of <24 cmolc kg−1 clay. Based on the study 3rd horizon of Pedon-2 and Pedon-5, and 2nd and 3rd horizons of Pedon-6 fulfilled the requirements of Sideralic properties (Table 6).

Abrupt textural difference is a very sharp increase in clay content within a limited depth range. In the underlying layer ≥8% clay, and within ≤5 cm depth ≥20% increase in clay content if the overlying layer has ≥20% clay. Accordingly, 2nd and 3rd horizons of Pedon-3 and Pedon-7 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Abrupt textural difference (Table 6).

Hypereutric is a layer that has ≥30 cm thick between 25 and 150 cm, Munsell color hue redder than 5YR and value of <4 in moist state. The ratio of base saturation to effective base saturation is ≥50% throughout between 20 and 100 cm.

3.4.3. The classification of pedons

The soils of Pedon-1 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Umbric horizon, Nitic horizon, and Anthric properties. Then they were classified as Hypereutric Anthroumbric Rhodic Nitisols (Aric). The soils cover 970 ha or 22% of the sub-watershed area (Fig. 4). Soils from a nearly similar ecological zone in northeastern Ethiopia with >50% base saturation were classified as Rhodic Nitisols (Eutric) [52].

Fig. 4.

Soil type map of Upper Hoha sub-watershed.

Pedon-2 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Mollic horizon, Nitic horizon, Anthric properties and Sideralic properties. Then the soils were classified as Hypereutric Anthromollic Sideralic Nitisols (Aric), covering 499 ha of land or 12% of the sub-watershed (Fig. 4).

The soils of Pedon-3 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Mollic horizon, Cambic horizon, Plinthic horizon, Sideralic properties and Abrupt textural difference. Having met these criteria, soils of Pedon-3 were classified as Hypereutric Rhodic Plinthic Cambisols (Geoabruptic, Clayic, Aric, Humic), covering 667 ha or 15% of the sub-watershed area. In western Ethiopia soils of the Abobo area, where the altitude is lower than the Upper Hoha sub-watershed, had Mollic surface diagnostic horizon and Cambic subsurface diagnostic horizon with >50% base saturation were classified as Haplic Cambisols (Eutric) [53].

The soils of Pedon-4 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Umbric horizon, Nitic horizon, Ferralic horizon and Anthric properties. Then the soils were classified as Hypereutric Anthroumbric Rhodic Ferralic Nitisols (Aric, Humic). The soils cover 964 ha of land or 22% of the sub-watershed. The same study carried out on Northwestern, Western and Central parts of Ethiopian soils by the CASCAPE project characterized Eutric Rohodic Nitisols with nearly similar morphological and physicochemical properties [44].

The soils of Pedon-5 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Umbric horizon, Nitic horizon and Sideralic properties; accordingly, the soils were classified as Orthoeutric Umbric Rhodic Sideralic Nitisols, covering 338 ha of land or 8% of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed area (Fig. 4). A study conducted on soils of Western Ethiopia in Bako Tibe District in nearly similar ecology was classified as Umbric Nitisols with base saturation less than 50% [39].

The soils of Pedon-6 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Umbric horizon, Cambic horizon, Pisoplinthic horizon and Sideralic properties; the soils were classified as Umbric Pisoplinthic Plinthosols (Clayic, Hypereutric), covering 513 ha of land or 12% of the sub-watershed (Fig. 4).

The soils of Pedon-7 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Mollic horizon, Nitic horizon, abrupt textural difference and colluvic material; therefore, the soils were classified as Hypereutric Mollic Nitisols (Colluvic, Profundihumic), covering 395 ha of land or 9% of the sub-watershed (Fig. 4).

4. Conclusion

The morphological and physicochemical properties of the soils indicated that there are three reference soil groups (RSG): Nitisols, Cambisols and Plinthosols. Nitisols of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed are formed by high rainfall and temperature of the area acting over the parent materials. Intensive hydrolysis combined with leaching of silica and bases from decomposed minerals and rocks produced highly weathered Nitisols. In addition, the topography of the area has its part in formation of the soils because Nitisols are mostly found in moderate slopes that enhance translocation of soluble substances and clay particles from surface horizons to subsurface horizons. Soil organisms have contributed to biological pedoturbation in giving gradual or diffuse horizon boundary. The soils are largely found on gentle to plain fields of western Ethiopia. Cambisols of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed are formed in where pedogenetic development of soils is slow because of undulated topography of the land. The effect of land slope makes low infiltration and percolation of rainwater down to the soil profile as a result less hydrolysis reaction occurs within the soil profile. The landform also makes the soil susceptible to erosion and causes sparse vegetation on the land which lessens the development of soils. Cambisols are dominant in northern, central, eastern and southern parts of the country where soil formation is not suitable. Plinthosols of the Upper Hoha sub-watershed are formed by hot and humid climatic conditions of the area that create seasonal variation of moisture in soils by the alternate cycling of dry and rainy seasons. Then, repeated wetting and drying of the humus poor mixture of kaolinitic clay with quartz and iron-rich primary minerals (biotite, olivine, pyroxenes, amphibole, etc) change irreversibly to a hardpan called plinthites through a redoximorphic process forming Plinthosols. They are found on rolling lands to gentle slopes around river banks, especially in the Blue Nile river basin. Generally, the three major soils had low pH, low available P, high available Fe and Mn, and low base saturations especially in the subsurface horizons; these constraints make the soils unproductive for agricultural production. However, the soil acidity, less availability of P and high solubility of Fe and Mn of Nitisols, Cambisols and Plinthosols can be managed by liming and fertilizer application. Then, the Nitisols can be used for cultivation of any type of agricultural crops but the Cambisols and Plinthosols can be used only for annual crops and forage crops which have shallow rooting depth due to the presence of the plinthic horizon that impedes plant root development.

Author contribution statement

Mathewos Bekele Wakwoya: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Wassie Haile Woldeyohannis and Fassil Kebede Yimamu: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

Doctor Mathewos Bekele Wakwoya was supported by Ministry of Education, Ethiopia [4534/2018].

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare that they have no known cmpeting finantial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The first author is indebted to Assosa University for giving him the chance of further study; and to Hawassa University for hosting him as a PhD candidate. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Education also deserves special thanks for providing research fund.

References

- 1.IUSS Working Group WRB . 2015. World reference base for soil resources 2014, Update 2015. (International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps. World Soil Resources Reports No 106. Rome, Italy). [Google Scholar]

- 2.FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) fourth ed. 2006. Guidelines for Soil Description. Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi X.Z., Yu D.S., Warner E.D., Sun W.X., Petersen G.W., Gong Z.T., Lin H. Cross-reference system for translating between genetic soil classification of China and soil taxonomy. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. 2005;70(1):78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kebeney S.J., Msanya B.M., Ng’etich W.K., Semoka J.M.R., Serrem C.K. Pedological characterization of some typical soils of Busia County, Western Kenya: soil morphology, physico-chemical properties, classification and fertility trends. Int. J. Phys. Soc. Sci. 2015;4(1):29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinku D., Sheleme B., Nand R., Fran W., Tekleab S.G. Effects of topography and land use on soil characteristics along the toposequence of Ele Watershed in Southern Ethiopia. Catena. 2014;115:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abay A., Sheleme B., Fran W. Characterization and classification of soils of selected areas in Southern Ethiopia. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015;5(11):116–137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isola J.O., Asunlegan O.A., Abiodun F.O., Smart M.O. Effect of soil depth and topography on physical and chemical properties of soil along Federal College of Forestry, Ibadan North West, Oyo State. J. Res. For., Wildlife & Environ. 2020;12(2):382–390. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fite G., Abdenna D., Wakene N. 2007. Influence of small scale irrigation on selected soil chemical properties. (Utilization of Diversity in Land Use Systems: Sustainable and Organic Approaches to Meet Human Needs. Witzenhausen, Germany). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eshetu L. School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2011. Assessment of Soil Acidity and Determination of Lime Requirement for Different Land Use Types: the Case of Degem Wereda, North Shoa Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia. MSc. Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karuma A., Gachene C.K.K., Msanya B.M., Mtakwa P.W., Amuri N., Gicheru P. Soil morphology, physicochemical properties and classification of typical soils of Mwala District, Kenya. Int. J. Phys. Soc. Sci. 2015;4(2):156–170. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geissen V., Sánchez-Hernández R., Kampichler C., Ramos-Reyes R., SepulvedaLozada A., Ochoa-Goana S., De Jong B.H.J., Huerta-Lwanga E., Hernández-Daumas S. Effects of land-use change on some properties of tropical soils: an example from Southeast Mexico. Geoderma. 2009;15:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Njuguna J.W. University of Nairobi; Kenya: 2019. Pedological characterization and classification of selected typical soils of Yala Basin, Kenya. Special Project Report. (Land Resource Management and Agricultural Technology). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aklilu A.G. The status of ecosystem resources in Ethiopia: potentials, challenges and threats: review paper. Bahir dar environment and forest research center. Journal of Biodiversity and Endangered Species. 2018;6(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engdawork A. Center for Environment and Development : Addis Ababa University; 2015. Characterization and Classification of the Major Agricultural Soils in CASCAPE Intervention Woredas: Bako-Tibe, Becho, Gimbichu, Girar-Jarso and Munessa Weredas in the Centeral Highlands of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolejole-Foreman C.M., Baylis K., Lipper L. 2012. Land degradation’s implications on agricultural value of production in Ethiopia: a look inside the bowl. (Selected Paper Prepared for Presentation at the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) Triennial Conference, Foz do Iguacu, Brazil). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endalkachew F., Kibebew K., Bobe B., Asmare M. Characterization and classification of soils of Yikalo Subwatershed in Lay Gayint District, Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2018;7(2):151–166. [Google Scholar]

- 17.FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States) 1984. Provisional Soil Map of Ethiopia. Land Use Planning Project, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 18.FAO (Food and Agriculture organization of the United Nations) 1998. The Digital Soil and Terrain (SOTER) database and maps oF North-East Africa. (Land and Water Digital Media Series 2. Rome, Italy). [Google Scholar]

- 19.CSA (Central Statistics Authority) 2009. The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Population Census Commission. Administrative Report, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 20.MoA (Ministry of Agriculture) 2000. Agro-ecological Zonation of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 21.ENMA (Ethiopian National Meteorology Agency), Benishangul Gumuz Region Service Center . 2018. The 2008-2017 Temperature and Rainfall Data of Assosa and Bambasi Districts. Meteorological Data Coordination and Climatology Case Team. Assosa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 22.ADADO (Assosa District Agriculture Development Office) 2018. The 2017/2018 Year 4th Quarter Work Achievement Report. (unpublished) [Google Scholar]

- 23.CSA (Central Statistical Agency) 2017. Agricultural Sample Survey 2016/2017. Report on: Area and Production of Major Crops (Private Peasant Holdings, Meher Season). Statistical Bulletin-584. Volume-I, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blades M. 2013. The Age and Origin of the Western Ethiopian Shield. (A Thesis Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements of the University of Adelaide for an Honours degree in Geology) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mengesha T. 1991. Geology of Kurmuk and Assosa Area. (Ethiopian Geological Survey. MS (digital version) EGS, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natnael W. School of Earth Science, Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2017. Petrogenesis of Granitoid Rocks of Assosa Area, Western Ethiopia. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 27.EMA (Ethiopian Mapping Agency) 1985. Topographic Map of Assosa District Map Code: 1034D3. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munsell Soil Color Book . 2015. Munsell Soil Color Charts with Genuine Munsell Color Chips. Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Reeuwijk L.P. sixth ed. ISRIC (International Soil Reference Information Center). FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); 6700AJ Wageningen, the Netherlands: 2002. Procedures for Soil Analysis. Technical paper 9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouyoucos G.J. A Re-calibration of the hydrometer methods for making mechanical analysis of soils. Agron. J. 1951;43:434–438. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walkley A., Black C.A. An examination of digestion method for determining soil organic matter and proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934;37(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bremner J.M., Mulvaney C.S. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part Two. Chemical and Microbiological Properties. second ed. Page A.L., Miller R.H., Keeney D.R., editors. American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America; Madison, Wisconsin, USA: 1982. Total Nitrogen; pp. 595–624. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen S.R., Cole C.V., Watanabe F.S., Dean L.A. United States Department of Agriculture; Washington DC, USA: 1954. Estimation of Available Phosphorus by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. USDA Circ. 939. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Reeuwijk L.P. fourth ed. International Soil Reference and Information Center; Wageningen, The Netherlands: 1993. Procedures for Soil Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summer E.M. In: Reference Soil and Media Diagnostic Procedures for the Southern Region of the United States, Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin Number 374, Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station. Donohue S.J., editor. VPI & SU; Blacksburg, Virginia, USA: 1992. Determination of exchangeable acidity and exchangeable Al using 1N KCl; pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan K.H. Marcel Dekker; New York, USA: 1996. Soil Sampling, Preparation, and Analysis; pp. 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheleme B. Characterization of soils along a toposequence in Gununo area, southern Ethiopia. J. Sci. Dev. 2011;1(1):31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boul W.S., Southard J.R., Graham C.R., Mcdaniel A.P. sixth ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: 2011. Soil Genesis and Classification. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berhanu D., Eyasu E. Characterization and classification of soils of Bako Tibe District, west Shewa, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2021;7(11) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Havlin J.L., Beaton J.D., Tisdale S.L., Nelson W.L. Prentice Hall; Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: 1999. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alemayehu R. 2015. Characterization of agricultural soils in CASCAPE intervention woredas in Western Oromia Region. (CASCAPE (Capacity Building for Scaling up of Best Practices in Agricultural Production in Ethiopia). Addis Ababa, Ethioipia). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eyasu E. Characteristics of Nitisols profiles affected by land use type and slope class in some Ethiopian Highlands. Environ. Syst. Res. 2017;6(20):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landon R.J. Routledge; New York, USA: 2014. Booker Tropical Soil Manual. A Handbook for Soil Survey and Agricultural Land Evaluation in the Tropics and Subtropics. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eyasu E. CASCAPE Project, ALTERA, Wageningen University and Research Centre (Wageningen UR); The Netherlands: 2016. Soils of the Ethiopian Highlands: Geomorphology and Properties. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young R.A. Faculty of the Graduate College at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; Lincoln, Nebraska, USA: 2015. Phosphorus Release Potential of Agricultural Soils of the United States. A Dissertation and Thesis in Natural Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alem H.H., Kibebew K., Heluf G. Characterization and classification of soils of Kabe Subwatershed in South Wollo Zone, Northeastern. Afr. J. Soil Sci. 2015;3(7):133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hazelton P., Murphy B. second ed. University of Sydney, Department of Natural Resources. CSIRO Publishing; Collingwood, Australia: 2007. Interpreting Soil Test Results. What Do All the Numbers Mean? [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniel A., Tefera T. Characterization and classification of soils of Aba-midan sub-watershed in Bambasi Wereda, West Ethiopia. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2016;6(6):390–399. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barrett W., Chu P., Coleman G., Goff D., Griffith L., Hohla J., Jones N., Pohlman K., Poole H., Spiva C., Zwiep J. Midwest Laboratories; Omaha, USA: 2017. Agronomy Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Wispelaere L., Marcelino V., Regassa A., De Grave E., Dumon M., Mees F., Van Ranst E. Revisiting nitic horizon properties of Nitisols in SW Ethiopia. Geoderma. 2015;243–244:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 51.FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) 1998. World reference base for soil resources. (ISSS–ISRIC–FAO. World Soil Resources Report No. 84. Rome, Italy). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Workat S., Enyew A., Hailu K. Characterization and classification of soils of Zamra Irrigation Scheme, Northeastern Ethiopia. Air Soil. Water Res. 2021;14:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teshome Y., Shelem B., Kibebew K. Characterization and classification of soils of Abobo Area, Western Ethiopia. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2016;8:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wysocki D.A., Schoeneberger P.J., Hirmas D.R., LaGarry H.E. In: Handbook of Soil Science: Properties and Processes. second ed. Huang P.M., Li Y., Sumner M.E., editors. Chemical Rubber Company Press; Boca Raton, Florida, USA: 2011. Geomorphology of soil landscapes; pp. 29.1–29.26. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.