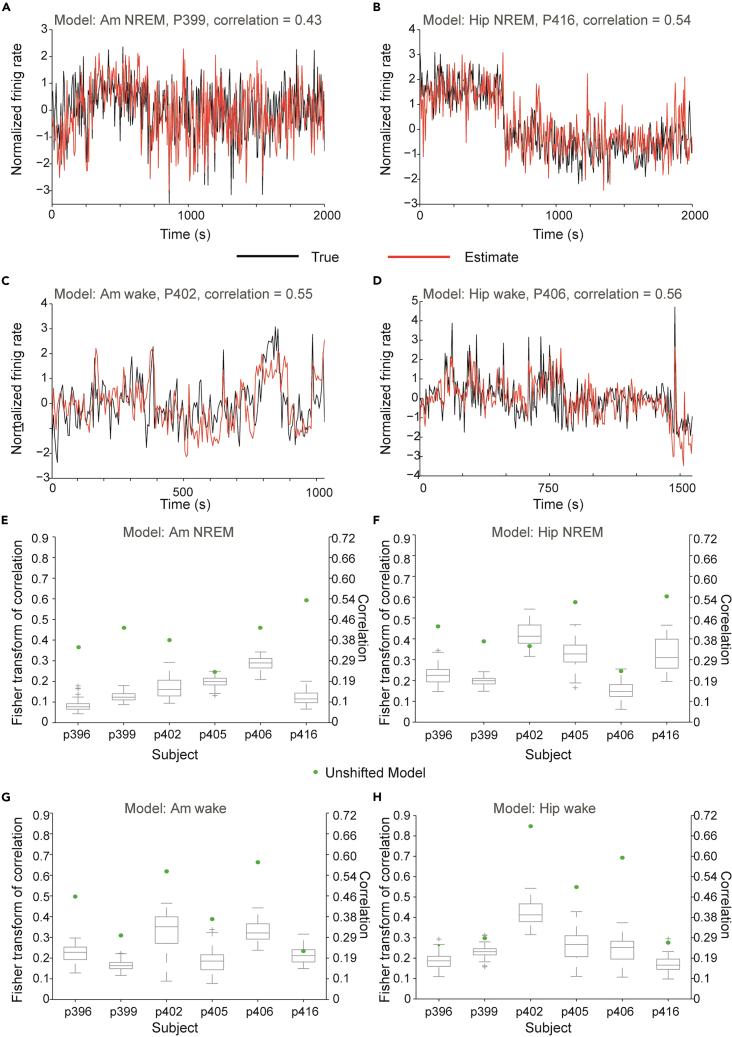

Figure 3.

Model accuracy can be attributed to both short- and long-term changes in firing rates

(A–D) True (black trace) vs. predicted (red trace) average unit activity after transformation (see STAR Methods) of the amygdala (A and C) from subjects p402 and p399, and hippocampus (B and D) from subjects p406 and p416 —during awake and non-REM sleep periods. The prediction is calculated using the train model without splitting to test and train periods. The overall correlation, which is stated in each graph, is composed from short- and long-term correlations.

(E–H) Fisher transform of the Pearson correlation between true and predicted firing rate for the amygdala (E and G) and hippocampus (F and H) during awake (E and F) and non-REM sleep (G and H) periods for the unshifted model (green dots) and boxplot of the fisher-transformed correlations for the shifted models (gray). Central mark indicates the median, and the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data point within 1.5 times the interquartile range; data points that are considered as potential outliers are marked in + sign. Note that in 19 of the 24 cases the correlation of the unshifted model is in the outlying region and in 17 of the 24 it is the most extreme point lying far away from the upper quartile. Indicating in these cases that the correlation can be attributed to short-term fluctuations in the firing rate. Right y axis indicates the untransformed Pearson’s correlation values.