Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced awareness that the health of populations is inextricably linked around the globe. Nurses require increased knowledge and preparation in global health. Nursing educators need examples of how to improve content in the curriculum.

Aims:

The purpose of this paper is to describe reconceptualization of a master’s level nursing course entitled “Population Health in a Global Society” to include global health competencies.

Methods:

We identified four global health competencies within the following three domains: globalization of health and healthcare; collaboration, partnering, and communication; and sociocultural and political awareness.

Implementation:

We utilized guest lectures, a panel discussion, discussion forums and an independent research assignment. The methods used were well received by students, and the content delivered improved their perceived knowledge in global population health.

Discussion:

The global health domains and competencies provided a roadmap for improving our course to focus on population health from a global perspective.

Conclusion:

In order to prepare nurses to contribute to global population health, population health courses should integrate global health competencies. The content of the revised course will better prepare nurses who will practice in a wide variety of settings and is designed for interdisciplinary education.

Keywords: global health, graduate nursing education, population health

1 |. BACKGROUND

To meet the healthcare needs of the 21st century will require a global health approach that addresses population-level needs (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the linkages between the health states of populations across global regions and among their respective social, economic, and political environments. Growing international trade and travel can result in foodborne illnesses or infectious outbreaks spreading easily across countries and devastating populations, especially those that are impoverished or historically marginalized, where housing is highly populated, households are multigenerational, and individuals have other exposure risks, such as use of public transit or being essential workers (Fawcett & Ellenbecker, 2015; Koplan et al., 2009). Furthermore, because the United States (U.S.) lags behind other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on metrics such as life expectancy and chronic disease rates (Tikkanen & Abrams, 2020), U.S. healthcare providers may benefit from learning about approaches to care from countries with better outcome metrics. Lastly, the documented health effects of climate change across the globe will require sustained international cooperation through appropriate financial flows, a new technology framework, and enhanced capacity building (United Nations, 2020).

“Global health” and “population health” share similarities but have distinct emphases. Global health emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions and synthesizes population-based prevention with individual-level care (Koplan et al., 2009). Population health emphasizes the interpersonal nature of health outcomes that affect “a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” (Kindig & Stoddart, 2003). Population health outcomes are influenced by social and structural contributors to health, for example, structural racism and the environments in which people live, work, and play, which influence health and must be targeted to improve outcomes. Initiatives to address population health therefore require more than a traditional medical approach and instead must target the social and economic contributors of poor health outcomes. COVID-19 has demonstrated how the health of the U.S. population can be affected by global events and that population health can only be tackled as a global initiative (Devakumar et al., 2020; White, 2020). Given that both population health and global health prioritize addressing the broader factors that contribute to health outcomes, and that the U.S.’ population health priorities of better quality of care, lower costs, and improved outcomes are issues across the globe, it is reasonable to conclude that addressing key population health challenges will require a global approach (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020).

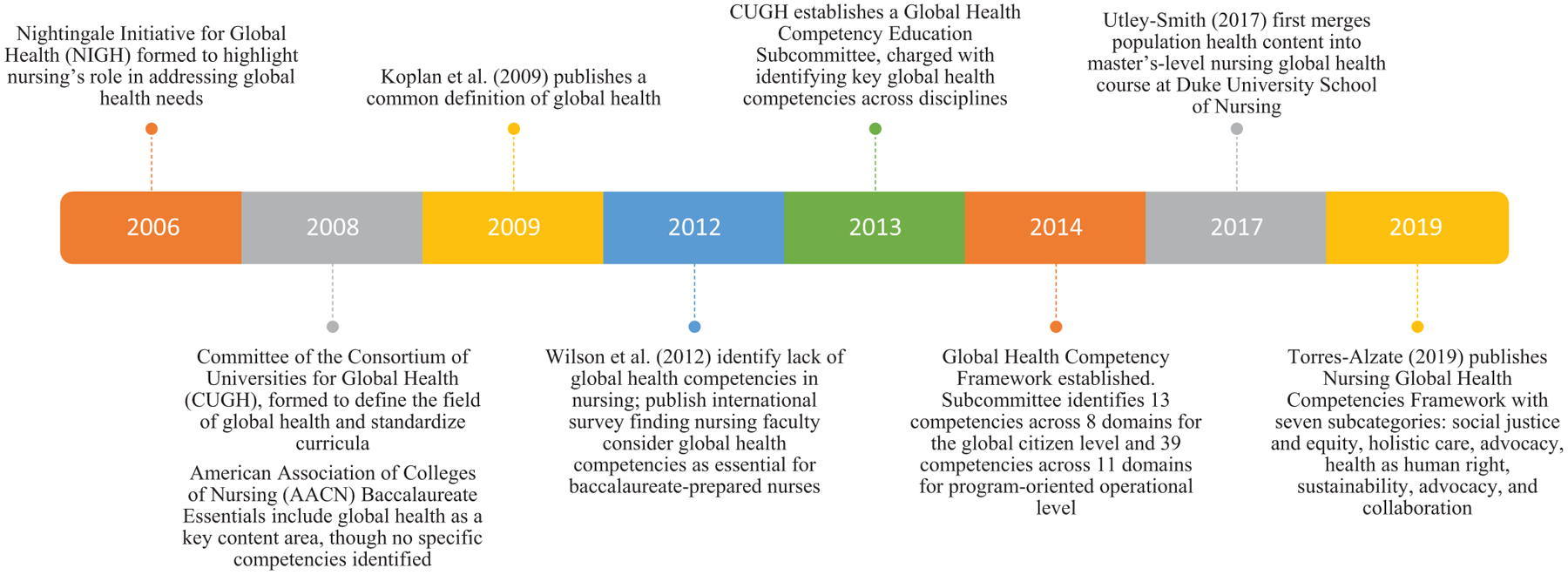

The Global Health Competency Sub-Committee, working under the Education Committee of the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH), developed guidelines for curricula and core global health competencies applicable across disciplines (CUGH, 2021). The competencies are a guide for teaching global content in a variety of disciplines to meet present and future global health challenges. The group intended these global health educational competencies to help form curricular standards for knowledge and practice in global health care. The committee recommended 82 evidence based core global health competencies with four competency levels: (1) Global Citizen Level, (2) Exploratory Level, (3) Basic Operational Level, and (4) Advanced Level. The Global Citizen Level encompasses 13 competencies within eight domains (Table 1) (Jogerst et al., 2015). A timeline illustrating the development of global health competencies and other relevant activities in nursing can be found in Figure 1.

TABLE 1.

List of domains and competencies for the global citizen bold text denotes a focus for enhancement in our course

| DOMAIN 1: Global burden of disease |

| Competency 1: Describe the major causes of morbidity and mortality around the world, and how the risk for disease varies with regions |

| Competency 2: Describe major public health efforts to reduce disparities in global health (such as Millenium Development Goals) |

| DOMAIN 2: Globalization of health and healthcare |

| Competency 3: Describe how travel and trade contribute to the spread of communicable and chronic disease |

| DOMAIN 3: Social and environmental determinants of health |

| Competency 4: Describe how cultural context influences perceptions of health and disease |

| Competency 5: List major social and economic determinants of health and their effects on the access to and quality of health services and on differences in morbidity and mortality between and within countries. |

| Competency 6: Describe the relationship between access to and quality of water, sanitation, food, and air on individual and population health. |

| DOMAIN 4: Collaboration, partnering, and communication |

| Competency 7: Exhibit interprofessional values and communication skills that demonstrate respect |

| Competency 8: Acknowledge one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities. |

| DOMAIN 5: Ethics |

| Competency 9: Demonstrate an understanding of and an ability to resolve common ethical issues and challenges that arise when working within diverse economic, political, and cultural contexts as well as when working with vulnerable populations and in low-resource settings to address global health issues |

| DOMAIN 6: Professional Practice |

| Competency 10: Articulate barriers to health and health care in low-resource settings locally and internationally |

| DOMAIN 7: Health Equity and Social Justice |

| Competency 11: Demonstrate a basic understanding of the relationships between health, human rights, and global inequities |

| Competency 12: Demonstrate a commitment to social responsibility |

| DOMAIN 8: Sociocultural and political awareness |

| Competency 13: Describe the roles and relationships of the major entities influencing global health and development |

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of global health competencies development and activities in nursing

As trusted professionals whose practice intersects social care and medicine, nurses are uniquely positioned to address population health challenges in a global context (Krumeich & Meershoek, 2014; Nightingale Initiative for Global Health, 2020). Yet, despite this increased focus on global and population health in nursing education, minimal literature to date has examined the delivery of population health curricular content within a global context. The purpose of this paper is to: (a) describe the reconceptualization of an existing population health course to integrate global health competencies and (b) evaluate the course’s impact on students’ knowledge related to these competencies.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Existing course

“Population Health in a Global Society” was a 3-credit course delivered via an online asynchronous modular format at the Duke University School of Nursing in Durham, North Carolina. The course was required in the first semester of the Masters of Science in Nursing Program and was also available to 4th semester Accelerated Bachelors of Science in Nursing students as an elective and to other students by request. Enrollment was typically 125–150 students in the fall and 75–100 students in the spring semesters. The goal of the course was to prepare graduate level nursing students to make evidence-based decisions to improve population health and reduce inequities between population groups across all settings of nursing practice. The focus was on examining population-level interventions that reflect an understanding of epidemiology, health policy, and social contributors to health using an ethical and global framework. Its five objectives were understanding conceptual models of population health, analyzing global population health issues using epidemiologic principles, evaluating ethical decision-making models to specific population health problems, exploring data sources to propose changes in care delivery models, and analyzing social contributors to health disparities. The course assigned readings, pre-recorded lectures, and videos as teaching strategies. Discussion forums, presentations, and quizzes assessed learning. Only one presentation focused on global health: students compared the U.S. with another country on either mortality rates or a specific health issue using data from the Global Health Observatory and reflected on what might account for differences. The first and last authors served as co-faculty in the course. The planning phase for implementation of the course revision was 18 months.

2.2 |. Existing support

The SON’s Office of Global and Community Health Initiatives provides financial resources to SON faculty who integrate global health concepts into nursing courses and specialties. The course co-faculty members met for three months to draft a grant application with two goals: (1) compare CUGH’s Global Health Competencies to existing course content and identify gaps and priority areas for content enhancement and (2) design teaching-learning strategies reflecting the preferred learning methods of students in the course (Utley-Smith, 2017). The SON’s Institute for Educational Excellence provided pedagogical guidance on delivery methods and evaluation.

2.3 |. Content gaps and teaching strategies

Whereas the objectives of the existing course had served chiefly to have students analyze and explore content, it was apparent to us that the global health competencies called for students to more actively engage- to acknowledge, describe, and exhibit. Unlike a student meeting the objectives of the existing course asked to explore and analyze data for their own learning, global citizens are called on to acknowledge their own limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities, exhibit interprofessional values, and describe content they’ve learned, more directly impacting the communities where they work and live. In addition to a more active engagement with the content, we identified three opportunities for major revisions. First, the comparison between U.S. and other countries provided little focus on globalization of health and healthcare or on the impact of travel and trade on global health. Second, collaboration and partnering were discussed in a U.S. context, with little focus on respectful communication and the limitations in skills, knowledge and abilities in a global context. Lastly, while sociocultural and political awareness were widely described in the U.S. context, there was no description of how these entities influence global health and development.

To add content, we planned for a combination of guest lectures and a guest panel from experts within and outside of Duke University, which would be recorded for asynchronous access by current and future students. Specifically, guests would address factors influencing health globally and the impact of travel and trade on disease We also broadened an existing presentation on health risks and trends to allow students to focus on a geographic area outside the U.S. Finally, previous discussion forum questions (What surprised you about the content this week? What do you wish you knew more about? Where would you go to find that information) were directed to include limitations of their knowledge, skills, and abilities in a global context and to consider how to demonstrate respectful communication with the faculty, guest lecturers (if they chose to submit questions), and their peers.

2.4 |. Integrating key global health content

Following receipt of the global health office award, we spent nine months on preparations to integrate the content into the course in the fall of 2019. Three domains, as identified by Jogerst et al. (2015), were selected for development in the revised curriculum. (1) Globalization of Health and Healthcare was defined as “focusing on understanding how globalization affects health, health systems, and the delivery of health care.” (2) Collaboration, Partnering, and Communication was defined as “the ability to select, recruit, and work with a diverse range of global health stakeholders to advance research, policy, and practice goals, and to foster open dialogue and effective communication with partners and within a team.” (3) Sociocultural and Political awareness was defined as “the conceptual basis with which to work effectively within diverse cultural settings and across local, regional, national, and international political landscapes.”

These particular domains and their associated competencies were chosen for the core course because our assessment of the course found that content in these areas was limited to a U.S. focus. Consequently, they guided our expansion of existing content on evidence-based comparisons between countries to include globalization, the interrelationships between countries, and the nurse’s role as global citizen. We were also committed in an introductory course to enable Master’s students to see their roles as collaborators within an interdisciplinary team, and to be prepared to work within a wide variety of settings and geographic locations with some degree of sociocultural and political awareness.

To develop the prescribed competencies, we focused on five course objectives, each with expected outcomes (Table 2). Objectives included: (1) analyze global population health issues using epidemiologic principles, (2) compare and contrast global financial models supporting population health, and (3) explore data sources that advanced practice nurses can use to propose changes in health care delivery models that best meet the needs of diverse populations, (4) analyze how social contributors to health affect health disparities and burden of illness, regionally, nationally, and globally, and (5) discuss ways in which conceptual models of population health apply to global healthcare practice. The objectives were consonant with existing SON Master’s Core Curriculum Concepts.

TABLE 2.

Map of global health domains, competencies, course objectives, and delivery methods

| Global health domain | Global health competency | Course objectives | Expected outcomes | Delivery methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Globalization of health and health care | Describe how travel and trade contribute to the spread of communicable and chronic disease | Analyze global population health issues using epidemiologic principles Compare and contrast global financial models supporting population health | Compare macro & microeconomics of chronic disease Select cost effective population interventions for chronic disease Assess models for improving chronic illness care Describe domestic, local and global environmental determinants of population health | Guest expert faculty recorded presentations (n = 2): The Global Health 2035 report and pathways to universal health coverage Sustainable Development Goals Faculty guest panelist discussed impact of rural-urban migration on health and functional status of older adults in China and India |

| Collaboration, partnering, and communication | Exhibit interprofessional values and communication skills that demonstrate respect Acknowledge one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities | Explore data sources that advanced practice nurses can use to propose changes in health care delivery models that best meet the needs of diverse populations | Apply methods of communicating health risk to populations. Identify examples of global community partnerships and important stakeholders for successful collaborations | Faculty member facilitated a panel of three guest faculty who described the value of both cultural humility and local partnerships as well as local and national entities in their work In discussion forums, students were asked to reflect on what was surprising to them, what they wished they knew more about, and where they would go for that information to acknowledge and address limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities |

| Sociocultural and political awareness | Describe the roles and relationships of the major entities influencing global health and development | Analyze how social contributors to health affect health disparities and burden of illness, regionally, nationally, and globally Discuss ways in which conceptual models of population health apply to global healthcare practice | Describe domestic, local and global environmental determinants of population health | Faculty member facilitated a panel of three guest faculty who described social, cultural, and political factors in Tanzania, Korea, and China respectively Students independently explored and presented social contributors to health/health risks/trends in any geographic regions of interest for their presentation |

During the integration phase of course revision, we reached out to content experts within the SON and across the university campus, as well as at other universities, to solicit suggestions for course content relative to the competencies and objectives. We relied on the extant literature and our professional networks to connect us to experts, and on the resources of our SON faculty, including visiting faculty members who practiced globally and university contacts in global health across campus. We emailed first authors of publications in relevant journals, asked contacts from our professional organizations for recommendations of faculty experts, and re-contacted nursing colleagues whom we had met at conferences to ask them to consider recommending content for our course. We planned with each guest lecturer/panelist what content they would share and recorded new material. Finally, we prepared an IRB application to use a survey evaluation of students’ awareness and perceived knowledge of global health content at the beginning and at the end of the semester.

3 |. IMPLEMENTATION

Delivery of the revised course utilized multiple teaching-learning strategies to achieve the expected outcomes of the course. Strategies included online interactive learning activities (presentations in which students researched an area of interest and shared what they learned with the entire class), weekly discussion forums in which students practiced collaborative and respectful communication, and two new guest faculty lectures and a guest faculty panel. These delivery methods are described below according to their primary contribution to global health competencies, but each method supported multiple competencies across all three Global Health domains.

3.1 |. Globalization of health and healthcare

To achieve these objectives and their expected outcomes, we collaborated with two faculty members from the Duke University Global Health Institute to produce a pre-recorded lecture. The Global Health Institute focuses on interdisciplinary education, research, implementing evidence-based interventions, and local, collaborative projects to find innovative solutions to the world’s most pressing global health challenges. The lecture focused on the report Global Health 2035, an investment global health framework prepared by the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health to address sustainable development goals, leveraging donor investments, and universal health coverage (Jamison et al., 2013). A faculty member from Duke University School of Nursing pre-recorded a lecture on Sustainable Development Goals. As well, the panel of guest faculty experts presented on the social contributors to health, including one faculty member who focused on the influence of rural-urban migration on the health and functional status of older adults in China.

3.2 |. Collaboration, partnering, and communication

To achieve competence in collaboration, partnering, and communication, students received dedicated class time to view the pre-recorded panel of nursing and visiting faculty who had lived and worked globally to improve health with communities in other countries. One faculty member lived in Tanzania and worked on access to care issues; one lived in China and worked on the impact of within-country migration; a third visiting faculty member from Korea presented research on the mental health of members of the service industry. Each panelist exhibited cultural humility and sensitivity, while discussing their roles in partnership with other disciplines and stakeholders, local and national entities, and their communities.

To address the competency centered on acknowledging one’s limitations and practicing communication skills that demonstrate respect, students were asked in weekly discussion forums to reflect on what was surprising to them, what they wished they knew more about, and where to go for that information. They also were expected to reply to peers in respectful ways that would deepen the dialogue and shared learning.

3.3 |. Sociocultural and political awareness

To address the competency of describing the roles and relationships of major entities influencing global health and development, all guest panelists were asked to address this in their relevant geographic regions. The first-author served as moderator and posed a series of questions regarding how the socially, economically, and politically structured environment shaped the health of the population of interest. We also broadened an assignment that focused previously on health risks and trends for one’s county of residence to give students the option of researching any global community of interest as long as the data sources were cited.

Additionally, while collaboration, partnering, and communication as well as sociocultural and political awareness are competencies needed for nurses to participate in climate change solutions, climate change content was not added to this course until about a year after the improvements described herein. Relatedly, an expanded focus on environmental and racial justice and health implications of pandemics came with the world events and course content updates made to the course in academic years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022.

4 |. EVALUATION METHODS AND MEASURES

Students enrolled in the course were invited to participate in a brief course improvement survey developed by the authors about the student’s awareness and perceived knowledge of global health content at the beginning and at the end of the semester. Of 15 items, the first five related to content revisions regarding global health; the remaining 10 items focused on fundamental masters-level skills and were not directly related to this project. The Likert-style response options were none (1), low (2), moderate (3), and high (4). All 15 questions were adapted from those used in an earlier version of this course (Utley-Smith, 2017). The end of semester survey also included additional author-developed items (n = 9) about the methods used to deliver this content. The Likert-style response options were no help (1), a little help (2), moderate help (3), and great help (4). University IRB approval was obtained. Participation of students was completely voluntary; no remuneration or participation credits for the course were offered.

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools (Harris et al., 2009) as hosted at the University. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests were employed to determine differences from pre- to post-course in levels of knowledge. Of the students enrolled in the course (N = 125), 25 students responded to the survey prior to the start of the semester, and 35 responded to the survey at the end of the semester. By design, no demographic information about students was captured.

Table 3 presents the differences in pre- and post-test results on the five relevant content items. Items that had a significant positive change with regard to knowledge acquisition across the course were: population health conceptual models that apply to global health care, ethical decision-making models, global health epidemiology, data sources that advanced practice nurses can use to propose changes in healthcare delivery, and global financial models. Table 4 presents the perceived helpfulness of specific delivery methods. Students found the learning activities the most helpful, followed by online lectures, and guest lectures/panels.

TABLE 3.

Wilcoxon matched pair tests for pre- and postcourse survey

| Knowledge areas | Presurvey mean (SD) | Postsurvey mean (SD) | Wilcoxon statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population health conceptual models that apply to global healthcare practice | 1.2 (0.4) | 2.1 (0.5) | 85.5 | <.001 |

| Ethical decision-making models for population specific health dilemmas | 1.3 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.6) | 97 | <.001 |

| Global financial models supporting population health | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.6) | 47 | .005 |

| Data sources that advanced practice nurses can use to propose changes in health care delivery | 1.4 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.6) | 47.5 | .001 |

| Global health epidemiology | 1.5 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.6) | 63.5 | .001 |

TABLE 4.

Perceived helpfulness of current course components

| Component | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Discussion groups | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Listening to online lectures | 2.7 (0.6) |

| Messages from instructor | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Course readings | 2.4 (0.9) |

| Learning activities | 2.8 (0.4) |

| Guest lectures and panels | 2.6 (0.6) |

| Interactions with instructor | 2.3 (0.9) |

| Information technology support | 1.9 (1.1) |

| Intervals between quizzes | 2.5 (0.9) |

5 |. DISCUSSION

This study suggests two primary findings. First, when an existing graduate level course – in this case on population health—proves inadequate to address emergent global conditions, a wide variety of evidence-based resources are available to nursing faculty to identify specific gaps in relevant content and competencies and to amend that course, to the end of producing competent practitioners. The current project was based on evidence published by 2019, enriched by feedback from the community of nursing and non-nursing scholars who have practiced and researched in global contexts. The content of the revised course addressed competencies within three domains set out by the CUGH.

More recent landmark reports, such as the WHO, International Council of Nurses & Nursing Now’s, State of the World’s Nursing 2020 and the NAM’s Future of Nursing: 2020–2030 report (2021) have highlighted the need for nurses at all levels to be prepared in core population health functions, including infectious disease prevention, chronic disease management, and improving access for all populations to high-quality care. Specifically, advanced practice nurses—present in 53% of countries globally—can manage nurse-led clinics, provide primary health care services to underserved populations, and build public and private partnerships to improve a population’s health (WHO et al., 2020). Regulatory bodies and organizations, such as the American Association of Colleges in Nursing (AACN), the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF), and the Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations (CPHNO) have therefore developed curriculum best practices for both undergraduate and graduate nursing students related to both population health and global health (AACN, 2020; Joyce et al., 2017; NONPF, 2013). Furthermore, the AACN has deemed as a Master’s Essential the ability of students to describe the health of populations beyond national borders, while integrating the relevant context of economic, political, and cultural systems (AACN, 2020). In addition, we now require readings on planetary health, which focuses on the sustainability of our civilization and the impact of inequitable resource consumption on the planet and human health.

Retrospectively, we found that the current project addressed priority areas of focus from the AACN Essentials (AACN, 2020), such as understanding global structures, systems, politics, and population health, as well as the directive to work within a global health framework and discuss refugee health, noted by the Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations (CPHNO, 2019). Faculty who undertake course revisions or fresh course designs to address global health issues may take early advantage of the products of these working groups, as well as of the process and outcomes of the current project in a leading graduate nursing program.

Second, a majority of the subset of students who answered the survey were highly receptive to and interested in both the content itself and various online course delivery mechanisms. The perceived helpfulness of IT support and instructor interaction ranked lowest, although this may be because the students required little IT support and had limited direct interaction with instructors, given the online asynchronous nature of the course. Future courses related to nursing and global health may benefit from designing course components to reflect Nursing Global Health competencies and administering pre- and post-course knowledge assessments containing questions pertaining specifically to those competencies (Torres-Alzate, 2019). These would include, for example, a focus on health implications of pandemics; ethical issues, equity, and social justice in global health, and social and environmental determinants of planetary health, which we added to more recent semesters of this course.

In particular, students reported significant knowledge gains in population health conceptual models. Population health conceptual models reflect the complex interactions of socioeconomic factors with nursing and healthcare activities that contribute to health outcomes (Fawcett & Ellenbecker, 2015). Positive knowledge gains in this area may therefore indicate increased student understanding of complex, multifaceted healthcare problems, as well as nursing’s role in addressing these issues.

Our findings also indicated increased knowledge gains in the content areas of ethical decision-making for population health dilemmas, global financial models supporting population health, and global health epidemiology. We also found positive knowledge gains in the area of data sources that advanced practice nurses may use to propose changes in healthcare delivery. Previous studies have shown significant gaps in knowledge areas of global population health across the nursing curriculum (Joyce et al., 2017); our study findings may indicate the usefulness of a course such as ours in preparing students in these knowledge areas. By focusing on advanced practice nursing students, our course may serve to prepare future advanced practice nurses to provide care for rural and medically underserved communities across global settings and diverse patient populations (WHO, International Council of Nurses & Nursing Now, 2020).

Finally, new delivery methods utilized in this course, such as guest lectures, a guest panel presentation, and learning activities including their own presentations to the class, were among the highest-rated course components. This finding suggests highly acceptable and replicable strategies to support global health competencies that improve population health education in nursing.

5.1 |. Limitations

In addition to its strengths, our work had important limitations that may be addressed by future educational initiatives. The limited number of respondents taking our evaluation survey limits the generalizability of our conclusions. We evaluated the integration of global health content in one course within the Master’s curriculum, which cannot address global health competencies across courses in the Master’s curriculum at our school or others. We relied only on survey data and did not track changes in the number of students who focused their presentations on geographic areas in the U.S. versus outside of the U.S., which would be an opportunity for future research. Finally, we relied on global health competencies that were not developed by or for nurses (Jogerst et al., 2015), and we did not have knowledge of the Nursing Global Health Competencies Framework (Torres-Alzate, 2019) when we applied for our grant in 2018. Neither did our project benefit from the Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations’ Key Action Areas Report submitted in 2019, nor the AACN essentials released in 2021.

5.2 |. Implications for education

Lessons learned from this course offer multiple opportunities for developing future Master’s level coursework. Continuing to refine this course to expand on other global health competencies (such as ethics and professional practice) and to provide real life exemplars of how these competencies can be applied in clinical practice may be beneficial. Examples of applications include opportunities for internships and clinical leadership roles that have a focus on maximizing clinical-academic collaborative partnerships to build capacity for improving health care services and delivery, policy development to impact global health clinical decisions and outcomes, and global health governance to inform global health programs. Additional competencies under current consideration include awareness of local and national codes of ethics relative to one’s working environment, and articulating barriers to health and healthcare in low-resource settings locally and internationally. Given the COVID pandemic that emerged after this course was implemented, expanded content on the spread of communicable diseases would be profitable for students.

Integrating this course with non-nursing disciplines, such as medicine, physical therapy, pharmacy, and social work, would offer opportunities for interdisciplinary learning experiences that mirror that of real-world health care delivery systems and support collaboration and communication skills. Additionally, engaging interdisciplinary organizations with a focus on global health, such as Global Health Council, offers the opportunity for students to expand their understanding, application and synthesis of global health competencies. Finally, evaluating competencies by advanced practice nurses post-graduation in a wide variety of clinical and geographic settings is warranted to assess the sustained impact of course content.

5.3 |. Implications for clinical practice

Nurses play a prominent role in health care throughout the world. Conceptual models of population health and nursing provide deeper understanding of complex topics, especially as health care shifts from a focus on individual diseases to an emphasis on population health (Fawcett & Ellenbecker, 2015). As a result of these improvements in knowledge and competencies, nurses will be better prepared to provide care to diverse global populations and across settings (Joyce et al., 2017; WHO et al., 2020). Furthermore, by considering (and addressing) the social contributors to health outcomes across populations, nurses will be better prepared to deliver care through a lens of health equity (NAM, 2021). This level of understanding may help nurses to shape policies about how care should be given and build health capacity within their own country while carefully considering what can be learned from how care is delivered elsewhere.

5.4 |. Implications for research

Future studies should utilize newer nursing-specific global health competencies, such as the Nursing Global Health Competencies Framework (Torres-Alzate, 2019), the Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations’ Key Action Areas Report (2019), the AACN essentials (2021), and resources to aid in course design and administration of pre- and post-course knowledge assessments. Future studies should also evaluate the number of students who, when given a choice, continue to focus on exploring areas in the U.S. for presentation and individual research, versus those who choose other geographic areas of interest. In addition to tracking changes in knowledge related to the more nursing specific competencies, and choice of engagement with global content, future studies should consider measuring use of the competencies post-graduation in a wide variety of clinical and geographic settings.

6 |. CONCLUSION

As health care continues to evolve and increasingly focuses on social contributors to health and root causes of poor outcomes, nurses will have a key role to play in improving population health across the globe. COVID-19 has indeed highlighted the interconnectedness of populations’ health status across global regions, and the role of global health in the U.S. As such, advanced practice nurse leaders must be adequately trained and prepared to apply global population health-based concepts in any setting of practice. Our course aimed to foster a broad understanding of population health in a global society. The results of our survey indicate some evidence of increases in knowledge and perceived helpfulness of the delivery methods we utilized. Our work contributes to the discussion of innovative ways to incorporate global population health into graduate nursing level curricula.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Queen Utley-Smith, on whose work our project was built. We also thank our guest faculty: Drs. Gavin Yamey, Wenhui Mao, Hanzhang Xu, Irene Felsman, Souk Young Kim, and Michael Relf, for contributing their content expertise to our course. We also thank the students in our course for their participation and feedback on these new course goals and objectives. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Judith Hays who provided editorial services. This work received funding support from the Duke University School of Nursing Office of Global and Community Health Initiatives (OGACHI) Curricular Infusion Grant.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- American Association of Colleges in Nursing. (2020). Population health nursing: Curriculum improvement. American Association of Colleges in Nursing. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Population-Health-Nursing [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). What is population health? https://www.cdc.gov/pophealthtraining/whatis.html [Google Scholar]

- Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) (2021). Committees and working groups. https://www.cugh.org/our-work/committees/

- Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations. (2019). Key action areas for addressing social determinants of health through a public health nursing lens. https://www.cphno.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/QCC-Report-to-NAM-FON2020-2030_2019.11.21-1.pdf

- Devakumar D, Shannon G, Bhopal SS, & Abubakar I (2020). Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Lancet, 395(10231), 1194. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30792-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, & Ellenbecker CH (2015). A proposed conceptual model of nursing and population health. Nursing Outlook, 63(3), 288–298. 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, Bustreo F, Evans D, Feachem RG, Frenk J, Ghosh G, Goldie SJ, Guo Y, Gupta S, Horton R, Kruk ME, Mahmoud A, Mohohlo LK, Ncube M, … Yamey G (2013). Global health 2035: A world converging within a generation. Lancet (London, England), 382(9908), 1898–1955. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V, Evert J, Fields E, Hall T, Olsen J, Rowthorn V, Rudy S, Shen J, Simon L, Torres H, Velji A, & Wilson LL (2015). Identifying interprofessional global health competencies for 21st-century health professionals. Annals of Global Health, 81(2), 239–247. 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce B, Brown-Schott N, Hicks V, Johnson RG, Harmon M, & Pilling L (2017). The global health nursing imperative: Using competency-based analysis to strengthen accountability for population focused practice, education, and research. Annals of Global Health, 83(3–4), 641–653. 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2019). The U.S. Government engagement in global health: A primer. https://www.kff.org/report-section/the-u-s-government-engagement-in-global-health-a-primer-report/ [Google Scholar]

- Kindig D, & Stoddart G (2003). What is population health? American Journal of Public Health, 93(3), 380–383. 10.2105/ajph.93.3.380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, & Wasserheit JN (2009). Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet, 373(9679), 1993–1995. 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumeich A, & Meershoek A (2014). Health in global context; beyond the social determinants of health? Global Health Action, 7(1), 23506. 10.3402/gha.v7.23506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Medicine (2021). The future of nursing 2020–2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculty. (2013). Population-focused nurse practitioner competencies. National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculty https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/Competencies/CompilationPopFocusComps2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale Initiative for Global Health (2020). Retrieved from https://www.nighvision.net/about-us.html [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen R, & Abrams MK (2020). Health Care from a global perspective, 2019: Higher spending, worse outcomes? The Commonwealth Fund, U.S. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019 [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Alzate H (2019). Nursing global health competencies framework. Nursing Education Perspectives, 40(5), 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nations United. (2020). Sustainable development goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/ [Google Scholar]

- Utley-Smith Q (2017). An online education approach to population health in a global society. Public Health Nursing, 34, 389–394. 10.1111/phn.12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A (2020). Education: equipping educators. Historical linkages: Epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia. Lancet, 395(10232), 1250–1251. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30737-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of the world’s nursing 2020: investing in education, jobs and leadership (2020). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.