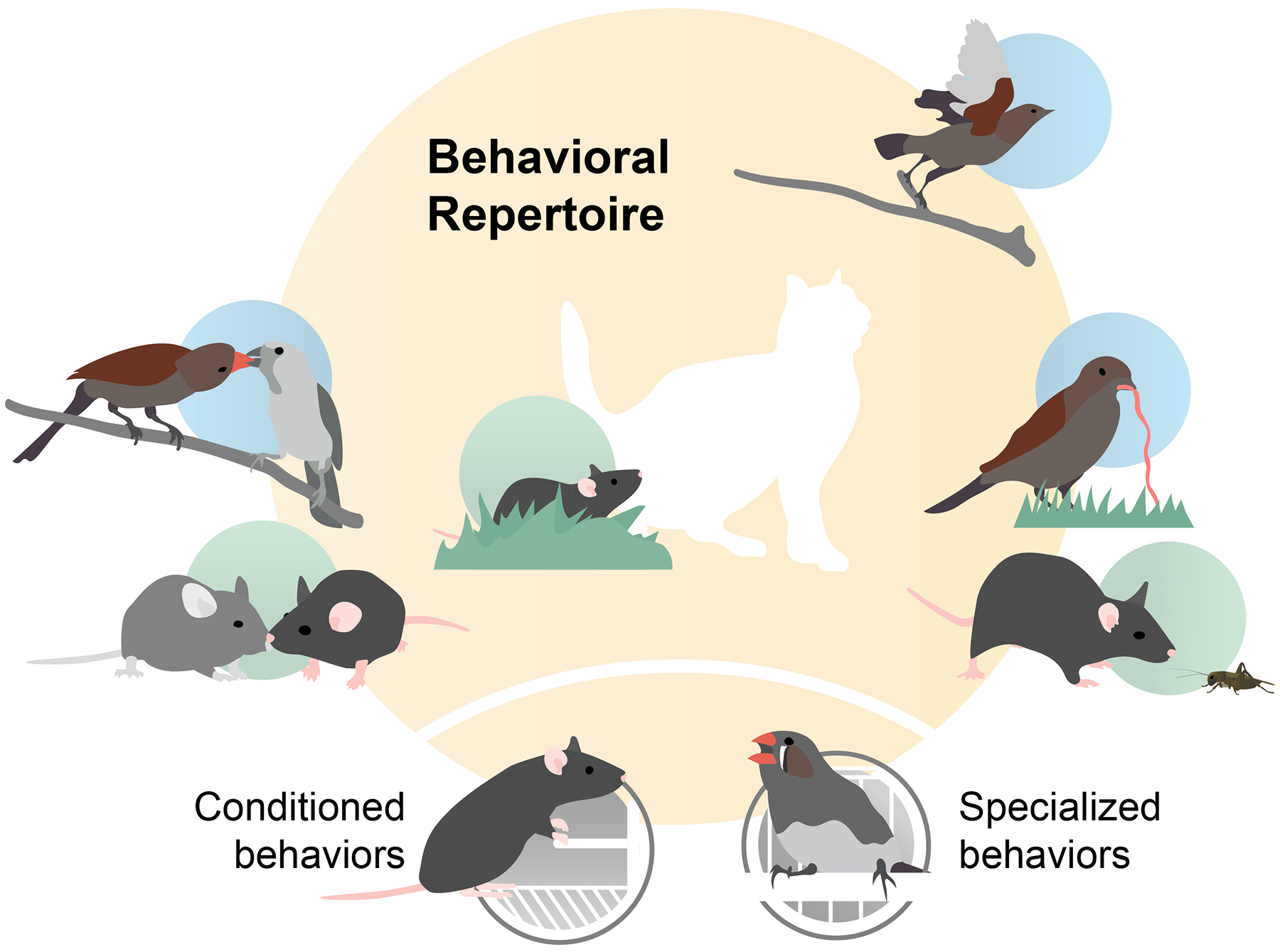

Figure 1. Animals have remarkably diverse behavioral repertoires.

The stereotyped conditioned and specialized behaviors that are typically studied in systems neuroscience and neuroethology are a small part of the range of behaviors they produce, many of which are shared across species (social interaction, predator avoidance, prey capture, and so on) but for which we know very little about the underlying neural mechanisms. For example, with the exception of spatial representations in the medial temporal lobe first pioneered by O’Keefe15–19, relatively few data are available that detail the effects of navigation and exploration on perceptual and cognitive functions20–22 despite the fact that the ability to move through space has both been a foundational pressure on brain evolution and routinely accounts for large portions of daily activity in all animals. Similarly, the neuroscience of the song learning behavior in oscines has been studied extensively generating unique insights into sequence motor learning but has taught us very little about brain mechanisms involved in natural vocal exchanges23. Spatial exploration and natural communication behaviors, however, are highly variable, making them difficult to study in conventional frameworks.