Abstract

Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) often experience weight loss during the follow-up period. However, the prevalence and clinical impact of weight loss in these patients still need to be elucidated. This retrospective single-center study reviewed 134 consecutive patients diagnosed with IPF. Weight loss of 5% or more over 1 year was defined as significant weight loss. Clinical data of patients were compared according to the significant weight loss. We analyzed whether the clinical impact of significant weight loss differed regarding the pirfenidone dose. The median follow-up period was 22.1 months. The mean age of patients was 67.3 years, and 92.5% were men. Of the 134 patients, 42 (31.3%) showed significant weight loss. Multivariate cox regression analysis revealed that significant weight loss was independently associated with mortality (hazard ratio [HR]; 2.670; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.099–6.484; p = 0.030) after adjusting for lung function and other significant risk factors (6-min walk test distance: HR, 0.993; 95% CI 0.987–0.998; p = 0.005). The median survival of patients with significant weight loss (n = 22) was relevantly shorter than that of those without significant weight loss (n = 43) in the reduced dose pirfenidone group (28.2 ± 3.3 vs. 43.3 ± 3.2 months, p = 0.013). Compared with patients without significant weight loss (n = 38), patients with significant weight loss (n = 15) also showed a marginally-significant shorter survival in the full-dose pirfenidone group (28.9 ± 3.1 vs. 39.8 ± 2.6 months, p = 0.085). Significant weight loss is a prognostic factor in patients with IPF regardless of pirfenidone dose. Vigilant monitoring might be necessary to detect weight loss during the clinical course in these patients.

Subject terms: Diseases, Medical research, Signs and symptoms

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis(IPF) is a specific form of interstitial lung disease characterized by chronic and progressive loss of lung function1. Although the clinical course of IPF varies widely, in general, the prognosis of IPF is poor, and the median survival is 3–5 years from the time of diagnosis2.

Weight loss is a common problem in patients with IPF. Previous studies have reported that approximately 15–20% of patients with IPF lose 5% of their weight during the first year of the disease course3,4. Various factors such as disease progression, chronic inflammation, and physical inactivity have been suggested as the cause of weight loss in patients with IPF5–7. In addition, anti-fibrotic medications to treat IPF, especially pirfenidone might cause weight loss8, often resulting in a dose reduction of these medications to minimize adverse effects9.

Several studies have reported that weight loss and low body mass index (BMI) can adversely affect the prognosis of patients with IPF3,4,10,11. However, other studies have shown conflicting results, depending on the confounding factor and study design12,13. Large-scale studies on the prevalence and clinical impact of weight loss in patients with IPF are still needed, especially in the era of anti-fibrotic medication usage, which is an important confounding factor. Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the prevalence, risk factors, clinical impact of weight loss in patients with IPF, and whether the clinical effects of weight loss differ in regard to the dose of pirfenidone.

Methods

Study population

In this single-center retrospective cohort study, we analyzed the data of patients aged 40 years and diagnosed with IPF at Asan Medical Center, a tertiary referral hospital in Seoul, South Korea between January 1, 2018, and September 1, 2021. Patients with a follow-up duration of less than a year, and patients with no data on body weight at the time of diagnosis or a year after diagnosis were excluded from the study. Patients with a definite connective tissue disease or a history of exposure to the possible causes of interstitial lung disease were also excluded.

Diagnosis of IPF was made by the diagnostic criteria of the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/Japanese Respiratory Society/Latin American Thoracic Association in 201814.

Clinical data

Body weight was measured at the time of diagnosis and the outpatient visit or hospitalization thereafter. Significant weight loss was defined as a weight loss of 5% over 1 year after diagnosis15,16. Data from the National Insurance Corporation were used to investigate deaths and their dates from the time of diagnosis to August 1, 2022. Consistent with ERS/ATS recommendations, spirometry was performed and, total lung capacity (TLC), and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco) were measured17,18. The 6-min walk test (6MWT) was also performed according to these guidelines19. We used in-hospital data to investigate the demographics of the patients, whether they used pirfenidone, the dosage and side effects of pirfenidone, and the types of side effects. We defined the use of pirfenidone as a prescription with pirfenidone for more than 3 months. As used in Korea, full dose of pirfenidone was defined as 1800 mg/d, and reduced dose of pirfenindone as < 1800 mg/d8,20.

Statistical analyses

For continuous variables, all values are presented as means ± standard deviations and categorical variables are presented as percentages. Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables.

The patients were divided into two groups: one with significant weight loss and one without. Logistic analysis was used to find risk factors for significant weight loss. Factors affecting mortality in patients with IPF were analyzed through the Cox proportional hazard analysis. Variables significant at a p value of 0.2 in the univariable analysis were candidates in the multivariable analysis. Survival analysis was performed to determine a difference in mortality between the two groups using the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and log-rank test.

All p-values were two-tailed, with statistical significance set at p 0.05. SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was endorsed by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB number: 2021-0736). This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design and anonymity of clinical data.

Results

Patients

A total of 134 patients were included in this study. The median follow-up duration was 22.1 months (interquartile range: 15.0–29.4 months). Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of patients according to significant weight loss. Most participants were male (92.5%) and ever-smokers (86.6%). Of the total patients, 42 (31.3%) had a significant weight loss during the follow-up period, and 92 (68.7%) did not.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Total | Group with significant weight loss | Group without significant weight loss | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 134 | 42 | 92 | |

| Age, years | 67.3 ± 8.2 | 67.3 ± 9.3 | 67.3 ± 7.8 | 0.985 |

| Male sex | 124 (92.5) | 41 (97.6) | 83 (90.2) | 0.171 |

| Ever-smokers | 116 (86.6) | 39 (92.9) | 77 (83.7) | 0.149 |

| Baseline body weight, kg | 69.2 ± 10.6 | 70.4 ± 11.2 | 68.6 ± 10.3 | 0.366 |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2 | 25.5 ± 3.06 | 25.9 ± 3.37 | 25.3 ± 2.90 | 0.294 |

| Weight change, kg/year | − 2.14 ± 4.99 | − 7.83 ± 3.81 | 0.45 ± 2.84 | < 0.001 |

| IPF diagnosis | ||||

| Clinical IPF | 103 (76.9) | 31 (73.8) | 78.3 | 0.571 |

| Biopsy proven IPF | 31 (23.1) | 11 (26.2) | 21.7 | |

| KL-6, U/mL (116, 36/80) | 1014.4 ± 874.9 | 922.3 ± 692.2 | 1055.8 ± 951.9 | 0.452 |

| Baseline albumin, g/dL (126, 40/86) | 3.67 ± 0.43 | 3.58 ± 0.45 | 3.72 ± 0.41 | 0.108 |

| Emphysema | 62 (46.3) | 17 (40.5) | 45 (48.9) | 0.364 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| COPD | 12 (9.0) | 2 (4.8) | 10 (10.9) | 0.339 |

| Lung cancer | 20 (14.9) | 11 (26.2) | 9 (9.8) | 0.013 |

| GERD | 16 (11.9) | 4 (9.5) | 12 (13.0) | 0.560 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 22 (16.4) | 8 (19.0) | 14 (15.2) | 0.579 |

| Pulmonary function test | ||||

| FVC, % predicted (129, 41/88) | 75.6 ± 13.7 | 72.5 ± 15.1 | 77.0 ± 13.0 | 0.086 |

| DLco, % predicted (124, 39/85) | 58.6 ± 16.8 | 53.9 ± 16.1 | 60.7 ± 16.8 | 0.035 |

| TLC, % predicted (112, 35/77) | 74.5 ± 12.4 | 73.0 ± 13.3 | 75.2 ± 12.1 | 0.393 |

| 6MWD, meter | 423.4 ± 99.9 | 414.0 ± 95.1 | 427.7 ± 102.8 | 0.468 |

| 6MWT, lowest SpO2, % | 90.4 ± 5.8 | 89.7 ± 5.5 | 90.8 ± 6.0 | 0.356 |

| GAP stage | ||||

| GAP stage I | 62 (46.3) | 16 (38.1) | 46 (50.0) | 0.193 |

| GAP stage II | 67 (50.0) | 23 (54.8) | 44 (47.8) | |

| GAP stage III | 5 (3.7) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (2.2) | |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range), or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. If a variable could not be measured in all patients, the number of patients for whom the variable was measured in total population and each group is indicated in parentheses next to the variables in the first column.

BMI body mass index, COPD chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, FVC forced vital capacity, DLco diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, IPF idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, TLC total lung capacity, 6MWD 6-min walk test distance, 6MWT 6-min walk test, SpO2 peripheral oxygen saturation, GAP Gender, Age, Physiology.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups; however, the DLco was significantly lower in the weight loss group (p = 0.035) than in the other group. Baseline body weight, BMI and GAP (Gender, Age, Physiology) class21 were not significantly different between two groups (p = 0.366, p = 0.294, and p = 0.193, respectively). Baseline Forced vital capacity (FVC) and albumin levels were lower in the significant weight loss group; however, the differences were marginally significant (FVC: p = 0.086, albumin: p = 0.108).

Patients with significant weight loss had an average weight loss of 7.83 kg over 1 year, and patients without significant weight loss had an average weight gain of 0.45 kg over 1 year (p < 0.001).

Use of pirfenidone and associated side effects

Most patients (88.1%, 118 of 134) received pirfenidone, and no significant difference was observed between the two groups regarding the pirfenidone dose, duration, and discontinuation of pirfenidone. (p = 0.518, p = 0.257, p = 0.722 respectively, Table 2). The median time period from the diagnosis of IPF to initiation of pirfenidone was 2.1 months (interquartile range: 0.3–6.6 months) and showed no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.213). Of all patients, 37.3% had gastrointestinal, 37.3% had skin, and 12.7% had both side effects. There was no significant difference in the frequency of each side effect according to significant weight loss (p > 0.999, p = 0.744, p = 0.774 for gastrointestinal, skin, and both side effects, respectively).

Table 2.

Use of pirfenidone and associated side effects in subgroups of patients by weight loss.

| Total | Group with significant weight loss | Group without significant weight loss | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 118 | 37 | 81 | |

| Pirfenidone full dose | 53 (44.9) | 15 (40.5) | 38 (46.9) | 0.518 |

| Pirfenidone reduced dose | 65 (55.1) | 22 (59.5) | 43 (53.1) | |

| Duration of pirfenidone therapy (months) | 17.6 ± 9.4 | 16.1 ± 9.8 | 18.2 ± 9.1 | 0.257 |

| Diagnosis to pirfenidone therapy (months) | 2.1 (0.3–6.6) | 2.0 (0.2–4.1) | 2.2 (0.4–7.7) | 0.213 |

| Discontinuation of treatment | 18 (15.3) | 5 (13.5) | 13 (16.0) | 0.722 |

| Side effect | ||||

| GI | 44 (37.3) | 14 (37.8) | 30 (37.0) | > 0.999 |

| Skin | 44 (37.3) | 13 (35.1) | 31 (38.3) | 0.744 |

| GI and skin | 15 (12.7) | 4 (10.8) | 11 (13.6) | 0.774 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation, n (%), median (interquartile range).

GI gastrointestinal.

Risk factors related to significant weight loss

No baseline characteristics including age, sex, smoking history, BMI, baseline albumin, emphysema, and 6MWT showed a relevant relation with significant weight loss, except comorbidity of lung cancer (odds ratio [OR] = 2.828, p = 0.047). Although DLco was identified as a statistically relevant risk factor for significant weight loss (odds ratio [OR] = 0.975, p = 0.038) in the univariate analysis, the multivariate analysis showed no statistical significance (OR = 0.984, p = 0.256, Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for weight loss.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Age, years | 1.000 | 0.956–1.045 | 0.985 |

| Male sex | 4.446 | 0.545–36.290 | 0.164 |

| Ever smokers | 2.532 | 0.692–9.274 | 0.161 |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2 | 1.065 | 0.947–1.199 | 0.294 |

| Baseline albumin, g/dL | 0.496 | 0.208–1.182 | 0.113 |

| Emphysema | 0.710 | 0.339–1.488 | 0.364 |

| COPD | 0.410 | 0.086–1.960 | 0.264 |

| Lung cancer | 3.272 | 1.237–8.656 | 0.017 |

| GERD | 0.702 | 0.212–2.320 | 2.320 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.311 | 0.503–3.415 | 0.579 |

| FVC, % predicted | 0.975 | 0.948–1.004 | 0.089 |

| DLco, % predicted | 0.975 | 0.952–0.999 | 0.038 |

| TLC, % predicted | 0.986 | 0.954–1.018 | 0.389 |

| 6MWD, meter | 0.999 | 0.995–1.002 | 0.465 |

| 6MWT, lowest SpO2, % | 0.972 | 0.914–1.033 | 0.355 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Male sex | 1.842 | 0.083–40.976 | 0.699 |

| Ever smokers | 1.947 | 0.208–18.200 | 0.559 |

| Baseline albumin, g/dL | 0.561 | 0.208–1.516 | 0.255 |

| Lung cancer | 2.828 | 1.015–7.877 | 0.047 |

| FVC, % predicted | 0.988 | 0.956–1.020 | 0.444 |

| DLco, % predicted | 0.984 | 0.958–1.011 | 0.256 |

BMI body mass index, COPD chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, FVC forced vital capacity, DLco diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, IPF idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, TLC total lung capacity, 6MWD 6-min walk test distance, 6MWT 6-min walk test, SpO2 peripheral oxygen saturation.

Factors affecting mortality and survival analysis

Table 4 demonstrates the Cox regression analysis of risk factors for mortality. The univariate Cox analysis showed that significant weight loss (hazard ratio [HR], 3.208; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.452–7.089; p = 0.004), baseline albumin (HR, 0.394; 95% CI 0.199–0.781; p = 0.008), FVC (HR, 0.974; 95% CI 0.945–1.003; p = 0.075), DLco (HR, 0.954; 95% CI 0.928–0.980; p < 0.001), 6-min walking distance [6MWD] HR, 0.993; 95% CI 0.990–0.997; p < 0.001), lowest oxygen saturation (SpO2) in 6MWT (HR, 0.928; 95% CI 0.879–0.979; p = 0.006), and use of pirfenidone (HR, 0.367; 95% CI 0.145–0.931; p = 0.035) were associated with mortality in patients with IPF. Although FVC and DLco were significantly associated with mortality in patients with IPF in univariate analysis, GAP stage was not significantly associated with mortality (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 4.

Cox regression analysis of risk factors for mortality.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Significant weight loss | 3.208 | 1.452–7.089 | 0.004 |

| Age, years | 0.997 | 0.952–1.043 | 0.890 |

| Male sex | 0.970 | 0.288–3.267 | 0.961 |

| Ever smokers | 1.739 | 0.520–5.816 | 0.369 |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2 | 0.938 | 0.818–1.075 | 0.357 |

| Baseline albumin, g/dL | 0.394 | 0.199–0.781 | 0.008 |

| COPD | 0.039 | 0.000–6.822 | 0.218 |

| Lung cancer | 1.886 | 0.639–5.563 | 0.250 |

| GERD | 0.476 | 0.112–2.024 | 0.315 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.042 | 0.846–4.930 | 0.112 |

| Pulmonary function test | |||

| FVC, % predicted | 0.974 | 0.945–1.003 | 0.075 |

| DLco, % predicted | 0.954 | 0.928–0.980 | < 0.001 |

| TLC, % predicted | 0.974 | 0.944–1.005 | 0.101 |

| 6MWD, meter | 0.993 | 0.990–0.997 | < 0.001 |

| 6MWT, lowest SpO2, % | 0.928 | 0.879–0.979 | 0.006 |

| Use of pirfenidone | 0.367 | 0.145–0.931 | 0.035 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Significant weight loss | 2.670 | 1.099–6.484 | 0.030 |

| Baseline albumin, g/dL | 0.499 | 0.207–1.201 | 0.121 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.389 | 0.487–3.962 | 0.538 |

| FVC, % predicted | 0.984 | 0.953–1.017 | 0.338 |

| DLco, % predicted | 0.974 | 0.940–1.009 | 0.139 |

| 6MWD, meter | 0.993 | 0.987–0.998 | 0.005 |

| 6MWT, lowest SpO2, % | 1.005 | 0.918–1.099 | 0.920 |

| Use of pirfenidone | 0.582 | 0.190–1.781 | 0.342 |

Among the significant variables in the univariate analysis, TLC (r = 0.974, p = 0.101) was excluded in the multivariate analysis due to close correlation with FVC.

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, COPD chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, FVC forced vital capacity, DLco diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, IPF idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, TLC total lung capacity, 6MWD 6-min walk test distance, 6MWT 6-min walk test, SpO2 peripheral oxygen saturation.

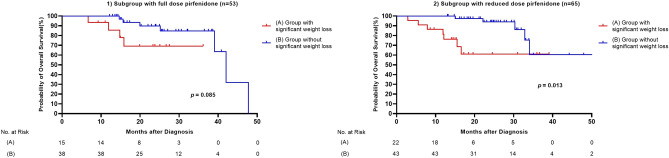

In the multivariate analysis, significant weight loss was independently associated with mortality (HR, 2.670; 95% CI 1.099–6.484; p = 0.030) after adjusting other risk factors. And 6MWD was also an independent risk factor of mortality (6MWD: HR, 0.993; 95% CI 0.987–0.998; p = 0.005). A comparison of survival curves between the patients with and without weight loss is shown in Fig. 1. The median survival of patients with weight loss was shorter than that of those without weight loss (29.4 ± 2.3 vs. 41.4 ± 2.1 months, respectively, p = 0.002).

Figure 1.

Comparison of survival curves between groups and without significant weight loss among patients with IPF. (A) Group with significant weight loss, (B) Group without significant weight loss.

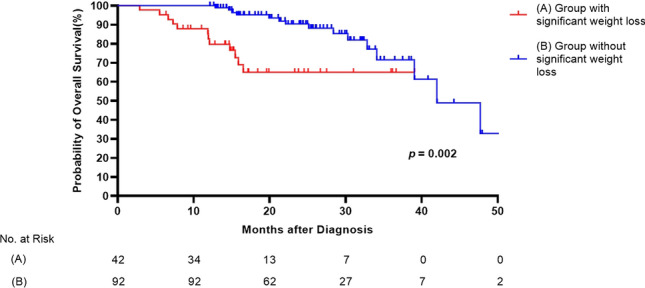

Clinical impact of weight loss according to the pirfenidone dosage

We analyzed whether the effect of significant weight loss on mortality differed according to the pirfenidone dose. The 118 patients treated with pirfenidone were divided into full-dose (1800 mg/d, 53 patients) and reduced-dose groups ( 1800 mg/d, 65 patients). Survival analysis was performed, and a Kaplan–Meier curve was plotted (Fig. 21,2). The median survival of patients with relevant weight loss was significantly shorter than that of those without significant weight loss in the reduced dose pirfenidone group (28.2 ± 3.3 vs. 43.3 ± 3.2 months, p = 0.013). In the full-dose group, the median survival was tended to be shorter in the weight loss group (28.9 ± 3.1 vs. 39.8 ± 2.6 months, p = 0.085).

Figure 2.

(1) Comparison of survival curves between groups with and without significant weight loss in a subgroup with full-dose pirfenidone (A) Group with significant weight loss, (B) Group without significant weight loss. (2) Comparison of survival curves between groups with and without significant weight loss in a subgroup with reduced dose pirfenidone (A) Group with significant weight loss, (B) Group without significant weight loss.

Discussion

In this study, 42 of 134 (31.3%) patients showed significant weight loss during the follow-up period. There were no differences in the usage and dosage of pirfenidone between the groups with and without significant weight loss. Significant weight loss had an independent effect on mortality even after adjusting for lung function and exercise capacity, and the subgroup analysis according to the pirfenidone dose showed similar results.

Although the exact mechanism of these findings needs to be clarified, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, physical inactivity, and poor general condition are proposed causes of weight loss in patients with IPF5,6,22,23. In this study, proportion of patients who had significant weight loss (31.3%) was higher than that of previous studies3,10. Nakatsuka et al. reported that the prevalence of significant weight loss in patients with IPF was 21.8% (27 of 124) in the Japanese cohort and 15.1% (13 of 86) in the English cohort3. Similarly, a retrospective cohort study by Jouneau et al. showed that 20.1% (85 of 423) of patients with IPF who took a placebo rather than nintedanib showed significant weight loss10. Interestingly, our current study showed that baseline low DLco was a risk factor for significant weight loss, though its association was not significant in multivariate analysis. The exact mechanism by which the decrease in DLco becomes the risk factor for weight loss is unclear, but a possible explanation is that emphysema or pulmonary hypertension often accompanies a decrease in DLco, and they could be causes of weight loss. Previous studies reported COPD, including emphysema could accompany weight loss24,25. Another reported that pulmonary hypertension also impairs functional status and quality of life26”. The following factors likely contributed to a higher proportion of patients having significant weight loss in our study compared with previous studies: first, in the general population, Asians have a lower body weight than Caucasians27; second, the number of patients who took pirfenidone in our study was higher than that of the previous study (88.1% of patients in our study took pirfenidone; 28.2% and 23.3% took pirfenidone in the Japanese and English cohorts by Nakatsuka et al. respectively; and 60.1% took nintedanib in the study by Jouneau et al.); and finally, the exclusion of patients who followed-up for 1 year from the study design might have affected the prevalence. Among patients with IPF, Asians also have a higher proportion of underweight patients than do Caucasians, suggesting regional and racial differences in the clinical course of IPF10,28.

Several previous studies have shown that weight loss might be associated with poor prognosis in patients with IPF. In Nakatsuka et al.’s retrospective cohort study of 210 patients, a weight loss of 5% was a significant risk factor for mortality (HR = 2.51, 95% CI 1.01–6.23, p = 0.047). Weight loss suggested a worse outcome even when FVC was normal3. Pugashetti et al. in a study with 225 patients with interstitial lung disease, reported that every 1% yearly decrease in BMI was associated with a 5% increase in mortality risk4. Furthermore, a recent report revealed that malnutrition is common in patients with IPF and associated with hospitalization and mortality, supporting the inference that weight loss adversely affects the prognosis of patients with IPF29.

Similar to the previous findings, significant weight loss was associated with poor outcomes in our study. It was associated with a poor prognosis even after adjusting for well-known prognostic factors such as 6MWD, baseline albumin levels, and lung function1,30,31. Therefore, it can be suggested that careful monitoring of weight loss is necessary when treating patients with IPF. Additionally, the GAP stage, which showed significant predictive ability for mortality in IPF patients21,32,33, was reported to be not associated in accurately predicting the prognosis in East Asia34,35. In this study, the GAP stage was not associated with mortality, either.

Although anorexia and weight loss are known side effects of pirfenidone7, there was no significant difference in the pirfenidone dose and the frequency of side effects between the significant and non-significant weight loss groups in our study. Pirfenidone therapy was started a median of 2.1 months after diagnosis of IPF and was administered for an average of 17.6 months. There was no significant difference in the time from diagnosis to the start of pirfenidone therapy and the duration of pirfenidone therapy according to weight loss.

Although the median survival was tended to be shorter in the weight loss group among patients who received full dose pirfenidone, the median survival of patients with relevant weight loss was significantly shorter in the reduced dose pirfenidone group. These finding suggest that weight loss might be still an important prognostic factor in patients with IPF using pirfenidone. Similarly, Jouneau et al. conducted a post hoc analysis of previous pirfenidone-related studies and suggested that patients whose BMI is 25 or who experienced weight loss in the placebo group showed a faster rate of FVC decline and worse prognosis36. Similarly, in the pirfenidone-treated group, patients with significant weight loss showed a worse prognosis than did those without significant weight loss36. However, nintedanib, another anti-fibrotic agent, showed different results in a previous study10. Although in the placebo group, the rate of FVC decline was faster in patients with a baseline BMI 25 than in patients with a BMI of 25 or more, FVC changes between each BMI group were similar in the nintedanib group10. Likewise, patients with significant weight loss suffered a relevantly faster decrease in FVC in the placebo group; however, the rate of FVC decline was not significantly different depending on significant weight loss in the nintedanib group10. Although some conflicting results have been reported between the two anti-fibrotic agents, weight loss might be an important composite outcome in patients with IPF who receive anti-fibrotic agents.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a single-center and retrospective study. Due to the retrospective design, we could not include all variables that could potentially affect mortality. In addition, as the retrospective design of the study, there might be some selection bias. In our current study, a total of 92.5% of study population were male patients, which was extremely higher compared to the other previous studies. However, among patients with probable usual interstitial pneumonia pattern, only old male with smoking history were considered as clinical IPF, for diagnostic certainty. Second, we could not specifically investigate the nutritional status and quality of life of the patients. However, we measured serum albumin level and used it as a surrogate for nutrition status. Third, in Korea, nintedanib is rarely used because it is not covered by health insurance; therefore, a detailed analysis of nintedanib could not be conducted in this study. And most of the patients included in this study took pirfenidone; therefore, we could not analyze the effect of weight loss on patients with IPF who did not take pirfenidone. Lastly, in Figs. 1 and 2, the survival difference between the two groups almost disappears at 30–40 months after diagnosis. In this study, the patient's median follow-up duration was 21.2 months (IQR 15.0–28.3). The insufficient amount of long-term follow-up patients might cause obscuration the survival difference between the two groups after 30–40 months. Further study with a longer duration is needed.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that significant weight loss might be an important prognostic factor in patients with IPF. Therefore, a vigilant monitoring is required to detect weight loss during the clinical course in patients with IPF.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- DLco

Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide

- TLC

Total lung capacity

- PFT

Pulmonary function test

- BMI

Body mass index

- 6MWD

6-minute walk test distance

- 6MWT

6-minute walk test

- SpO2

Peripheral oxygen saturation

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

Author contributions

H.C.K. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. J.K.L. and H.C.K. conceived and designed the study. J.K.L., C.C., J.K. and H.S.C. collected the data and reviewed medical records. J.K.L., C.C., J.K., H.S.C. and H.C.K. analysed and interpreted the data. J.K.L. and H.C.K. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2022R1C1C1005736).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-32843-7.

References

- 1.Lederer DJ, Martinez FJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1811–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1705751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King TE, Jr, Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakatsuka Y, Handa T, Kokosi M, Tanizawa K, Puglisi S, Jacob J, Sokai A, Ikezoe K, Kanatani KT, Kubo T, et al. The clinical significance of body weight loss in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Respiration. 2018;96:338–347. doi: 10.1159/000490355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugashetti J, Graham J, Boctor N, Mendez C, Foster E, Juarez M, Harper R, Morrissey B, Kadoch M, Oldham JM. Weight loss as a predictor of mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2018;52:1801289. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01289-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahmer T, Kirsten AM, Waschki B, Rabe KF, Magnussen H, Kirsten D, Gramm M, Hummler S, Brunnemer E, Kreuter M, Watz H. Clinical correlates of reduced physical activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration. 2016;91:497–502. doi: 10.1159/000446607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kliment CR, Oury TD. Oxidative stress, extracellular matrix targets, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:707–717. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proesmans VLJ, Drent M, Elfferich MDP, Wijnen P, Jessurun NT, Bast A. Self-reported gastrointestinal side effects of antifibrotic drugs in Dutch idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Lung. 2019;197:551–558. doi: 10.1007/s00408-019-00260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, Gorina E, Hopkins PM, Kardatzke D, Lancaster L, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song MJ, Moon SW, Choi JS, Lee SH, Lee SH, Chung KS, Jung JY, Kang YA, Park MS, Kim YS, et al. Efficacy of low dose pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Real world experience from a tertiary university hospital. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:21218. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77837-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jouneau S, Crestani B, Thibault R, Lederlin M, Vernhet L, Valenzuela C, Wijsenbeek M, Kreuter M, Stansen W, Quaresma M, Cottin V. Analysis of body mass index, weight loss and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2020;21:312. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01528-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulkarni T, Yuan K, Tran-Nguyen TK, Kim YI, de Andrade JA, Luckhardt T, Valentine VG, Kass DJ, Duncan SR. Decrements of body mass index are associated with poor outcomes of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doubková M, Švancara J, Svoboda M, Šterclová M, Bartoš V, Plačková M, Lacina L, Žurková M, Binková I, Bittenglová R, et al. EMPIRE registry, czech part: Impact of demographics, pulmonary function and HRCT on survival and clinical course in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin. Respir. J. 2018;12:1526–1535. doi: 10.1111/crj.12700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiyama O, Yamazaki R, Sano H, Iwanaga T, Higashimoto Y, Kume H, Tohda Y. Fat-free mass index predicts survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2017;22:480–485. doi: 10.1111/resp.12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, Behr J, Cottin V, Danoff SK, Morell F, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198:e44–e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahyoun NR, Serdula MK, Galuska DA, Zhang XL, Pamuk ER. The epidemiology of recent involuntary weight loss in the United States population. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2004;8:510–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong CJ. Involuntary weight loss. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2014;98:625–643. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26:511–522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, Johnson DC, van der Grinten CP, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Enright P, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26:720–735. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, Puhan MA, Pepin V, Saey D, McCormack MC, Carlin BW, Sciurba FC, Pitta F, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: Field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44:1428–1446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniguchi H, Ebina M, Kondoh Y, Ogura T, Azuma A, Suga M, Taguchi Y, Takahashi H, Nakata K, Sato A, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;35:821–829. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00005209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ley B, Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, Ryu JH, Tomassetti S, Lee JS, Poletti V, Buccioli M, Elicker BM, Jones KD, et al. A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:684–691. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahmer T, Kirsten AM, Waschki B, Rabe KF, Magnussen H, Kirsten D, Gramm M, Hummler S, Brunnemer E, Kreuter M, Watz H. Prognosis and longitudinal changes of physical activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017;17:104. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balasubramanian VP, Varkey B. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Effects beyond the lungs. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2006;12:106–112. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000208449.73101.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald MN, Wouters EFM, Rutten E, Casaburi R, Rennard SI, Lomas DA, Bamman M, Celli B, Agusti A, Tal-Singer R, et al. It’s more than low BMI: Prevalence of cachexia and associated mortality in COPD. Respir. Res. 2019;20:100. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Díaz AA, Pinto-Plata V, Hernández C, Peña J, Ramos C, Díaz JC, Klaassen J, Patino CM, Saldías F, Díaz O. Emphysema and DLCO predict a clinically important difference for 6MWD decline in COPD. Respir. Med. 2015;109:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitsiou G, Papakosta D, Bouros D. Pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A review. Respiration. 2011;82:294–304. doi: 10.1159/000327918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment (2000).

- 28.Faverio P, Bocchino M, Caminati A, Fumagalli A, Gasbarra M, Iovino P, Petruzzi A, Scalfi L, Sebastiani A, Stanziola AA, Sanduzzi A. Nutrition in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Critical issues analysis and future research directions. Nutrients. 2020;12:1131. doi: 10.3390/nu12041131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jouneau S, Rousseau C, Lederlin M, Lescoat A, Kerjouan M, Chauvin P, Luque-Paz D, Guillot S, Oger E, Vernhet L, Thibault R. Malnutrition and decreased food intake at diagnosis are associated with hospitalization and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Clin. Nutr. 2022;41:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Białas AJ, Iwański M, Miłkowska-Dymanowska J, Pietrzak M, Majewski S, Górski P, Piotrowski W. The prognostic value of fixed time and self-paced walking tests in patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Adv. Respir. Med. 2021;89:49–54. doi: 10.5603/ARM.a2020.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zisman DA, Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Belperio JA, Lynch JP, 3rd, Schwarz MI, Tayek JA, Reuben DB, Karlamangla AS. Serum albumin concentration and waiting list mortality in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Chest. 2009;135:929–935. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ley B, Bradford WZ, Weycker D, Vittinghoff E, du Bois RM, Collard HR. Unified baseline and longitudinal mortality prediction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;45:1374–1381. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkie M, Chalmers J, Smith R, Schembri S. P134 comparison of two prognostic tools for identifying high risk patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2012;67:A120–A120. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202678.417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SH, Park JS, Kim SY, Kim DS, Kim YW, Chung MP, Uh ST, Park CS, Park SW, Jeong SH, et al. Comparison of CPI and GAP models in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A nationwide cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4784. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kondoh S, Chiba H, Nishikiori H, Umeda Y, Kuronuma K, Otsuka M, Yamada G, Ohnishi H, Mori M, Kondoh Y, et al. Validation of the Japanese disease severity classification and the GAP model in Japanese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Investig. 2016;54:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jouneau S, Crestani B, Thibault R, Lederlin M, Vernhet L, Yang M, Morgenthien E, Kirchgaessler KU, Cottin V. Post hoc analysis of clinical outcomes in placebo- and pirfenidone-treated patients with IPF stratified by BMI and weight loss. Respiration. 2022;101:142–154. doi: 10.1159/000518855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.