Abstract

Introduction

The gender-age-physiology (GAP) index is an easy-to-use baseline mortality prediction model in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The GAP index does not incorporate exercise capacity parameters such as 6 min walk distance (6MWD) or exertional hypoxia. We evaluated if the addition of 6MWD and exertional hypoxia to the GAP index improves survival prediction in IPF.

Methods

Patients with IPF were identified at a tertiary care referral centre. Discrimination and calibration of the original GAP index were assessed. The cohort was then randomly divided into a derivation and validation set and performance of the GAP index with the addition of 6MWD and exertional hypoxia was evaluated. A final model was selected based on improvement in discrimination. Application of this model was then evaluated in a geographically distinct external cohort.

Results

There were 562 patients with IPF identified in the internal cohort. Discrimination of the original GAP index was measured by a C-statistic of 0.676 (95% CI 0.635 to 0.717) and overestimated observed risk. 6MWD and exertional hypoxia were strongly predictive of mortality. The addition of these variables to the GAP index significantly improved model discrimination. A revised index incorporating exercise capacity parameters was constructed and performed well in the internal validation set (C-statistic: 0.752; 95% CI 0.701 to 0.802, difference in C-statistic compared with the refit GAP index: 0.050; 95% CI 0.004 to 0.097) and external validation set (N=108 (C-statistic: 0.780; 95% CI 0.682 to 0.877)).

Conclusion

A simple point-based baseline-risk prediction model incorporating exercise capacity predictors into the original GAP index may improve prognostication in patients with IPF.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, interstitial fibrosis, respiratory measurement

Key messages.

What is already known on this topic

The gender-age-physiology (GAP) index is an easy-to-use baseline mortality prediction model in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Despite its practicality, the GAP index is limited by insufficient precision and the lack of evaluation of measures of exercise capacity.

What this study adds

Distance ambulated during 6 min walk testing and exertional hypoxia are strongly predictive of mortality in IPF and the addition of these factors to the GAP index improves overall model performance.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

The distance-oxygen-GAP index, a simple, point-based baseline-risk prediction model incorporating exercise capacity parameters into the GAP index improves mortality prediction in patients with IPF and has potential utility in research studies as well as clinical practice.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterised by progressive fibrosis that results in physiologic restriction, diminished exercise capacity and premature death. Despite a median survival of approximately 4.5 years, individuals demonstrate marked variability in their clinical decline.1–3

Given this clinical heterogeneity, multidimensional indices have been developed to predict course of illness based on clinical factors.4–8 An easy-to-use risk prediction model, the gender-age-physiology (GAP) index, was developed and validated in diverse patient populations.9–11 This model provides valuable insight through simple objective predictors of disease progression (gender, age, forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)). Despite its practicality, the model is limited by lack of precision and the overestimation of risk in some cohorts.4 12 Furthermore, the GAP index does not incorporate exercise capacity and therefore, may be of limited value in capturing decline over time.5 9 13

Exercise capacity testing, such as 6 min walk testing (6MWT) and the need for supplemental oxygen may outweigh other predictors of mortality in IPF and may outperform the predictive ability of the GAP index itself.10 14

We sought to build on the GAP index to develop and validate a simple, clinically useful predictive model incorporating exercise capacity which can be applied at the time of initial clinical evaluation.

Methods

We reviewed records of all patients with IPF evaluated at the Inova Advanced Lung Disease Program, a tertiary referral centre, between 1 December 2007 and 15 March 2020 (derivation and internal validation set) and all patients with IPF evaluated at the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou (Paris, France) between 15 July 2005 and 21 January 2021 (external validation set). Patients were included if confidently diagnosed with IPF based on available international consensus criteria at the time of evaluation and had pulmonary function testing available within 6 months of their initial clinic visit.15–17 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB# U20-03-3956 and CEPRO2021-029) at both institutions. Data were collected from the time of initial lung disease consultation and for up to 3 years. Outcome variables were obtained from the electronic medical record, the clinic databases and the Social Security death index.

Predictor variables

Predictor variables, in addition to those included in the original GAP index, were prespecified based on clinical relevance and evidence demonstrating their association with poor prognosis in IPF.10 14 Predictors evaluated were exertional hypoxia and the 6 min walk distance (6MWD). Categorical thresholds in the original GAP index were retained from the clinically meaningful categories defined in this prior model and a threshold for 6MWD of less than 250 m was selected a priori as the cutpoint most likely to best discriminate survival. 6MWD threshold selection was based on prior research in large cohorts, which found this distance to be independently associated with a greater than twofold increased risk of 1-year mortality.18 19

The 6MWD was included if performed within 6 months of the initial clinic evaluation. Exertional hypoxia was defined by either an active prescription for supplemental oxygen (for either previously documented severe resting or exertional hypoxemia related to IPF) or if desaturation (SpO2 <88%) was observed during the 6MWT performed on room air.20 Both 6MWT and pulmonary function tests were performed according to standard criteria with patients on chronic supplemental oxygen administered oxygen at their prescribed rate during the 6MWT.21 22 It is routine practice at both centres for all new consults to undergo pulmonary function testing and 6MWT during their initial consultation.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was time from baseline (defined as the date of initial pulmonary function test at our institution) to death from any cause. Patients were right censored at the time of loss to follow-up, end of follow-up and at the time of lung transplantation.

Statistical analysis

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test to compare groups. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) with the 95% CI to analyse individual risk factor of interest and their relationship to all-cause mortality. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals and was found to be valid. Necessary sample size (N=246) for model development was calculated using the method described by Riley et al for time-to-event analysis and was based on follow-up of 2.4 years, C-statistic of 68.7 (original GAP index validation) and estimated event rate of 22.8 cases per 100 person years.5 23 24 As all modelled variables were routinely collected at both study sites, incomplete data were infrequent (<1%), thus, missing data were handled via complete-case analysis.

We first evaluated the predictive performance of the original GAP index in the full study cohort using the previously validated categorised model with point-score assignments.5 We subsequently randomly split the internal cohort in half into a derivation and validation set using a sorting of the data based on automatically generated uniformly distributed random numbers. While retaining the original categories, the GAP index was refit in the derivation cohort and a screening procedure (a ‘base-model’ approach) was used to select a suitable model that optimised outcome prediction. Model discrimination with the GAP index plus additional predictors was compared with the refit GAP index primarily by the change in the Harrell’s C-statistic in the validation cohorts in accordance with published methodology.25 The incremental improvement of the two new predictors was also evaluated by category-free net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) for events, non-events and in aggregate at 1 year following initial pulmonary function testing. NRI measures whether risk increases in patients that ultimately died and likewise, if risk decreased in patients that ultimately survived. IDI is a similar metric, which incorporates the magnitude of risk change for each individual rather than simply the direction of change.26 Bootstrap resampling with 500 repetitions was used to calculate 95% bias-corrected CIs. New categories in the final model were assigned a point value by rescaling by a multiplicative factor of 5 (linear transformation to allow for maintained weighting of the original model) and rounding to the nearest whole integer of the regression coefficients estimated in the Cox regression model. A staging system was developed by organising point scores into three groups (40% with the lowest estimated risk, 40% with intermediate risk and 20% with the highest risk) to approximate subsequent risk in a method analogous to the original GAP index.5 Calibration of the final model was examined overall over 3 years of follow-up and by visual examination at multiple time points by comparing observed to predicted model values. The baseline cumulative hazard function was estimated from the internal derivation set and the relationship between observed to predicted model values was displayed graphically using calibration plots where the intercept of a well-calibrated model should not significantly differ from 0 and slope should not significantly differ from 1.27

As lung transplantation in IPF may alter expected survival, right censor of patients at the time of lung transplantation may introduce bias in the results. To explore this further, a sensitivity analysis using Fine and Gray competing-risk regression was performed treating lung transplantation as a competing risk. Finally, to explore utility in patients receiving IPF therapy and to ensure applicability to patients treated most contemporaneously, the discrimination of the selected point-score model was assessed in patients in the internal validation set treated with antifibrotics for at least 6 months and in those diagnosed with IPF within the last 5 years. All analyses were performed using STATA V.14 (StataCorp LP; College Station, Texas).

Results

Internal cohort characteristics

There were 611 patients diagnosed with IPF during the study period. Fourty-one patients were excluded given the inability to calculate a baseline GAP index and 8 patients were excluded for incomplete follow-up data. Totally, 562 patients qualified for analysis and were included in the final cohort.

Demographics, baseline characteristics and relevant pulmonary metrics of the cohort are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients in the internal cohort separated by randomly generated derivation and validation sets

| All patients | Derivation set | Validation set | |

| N=562 | N=281 | N=281 | |

| Age (years) | 72 (66, 77) | 72 (66, 77) | 71 (66, 76) |

| Gender, women | 129 (23.0) | 80 (28.5) | 49 (17.4) |

| Race, non-white | 126 (22.4) | 67 (23.8) | 59 (21.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.0±6.3 | 29.3±6.7 | 28.7±5.8 |

| Comorbid disease | |||

| Smoking status ever | 368 (65.5) | 179 (63.7) | 189 (67.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 115 (20.5) | 58 (20.6) | 57 (20.3) |

| Hypertension | 264 (47.0) | 121 (43.1) | 143 (50.9) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 178 (31.7) | 88 (31.3) | 90 (32.0) |

| Severe OSA | 128 (22.8) | 73 (26.0) | 55 (19.6) |

| Lung cancer | 10 (1.8) | 3 (1.1) | 7 (2.5) |

| Measures of IPF severity and management considerations | |||

| FVC (%) predicted | 65.6±19.1 | 66.4±19.2 | 64.8±18.9 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 83.0 (78.0, 87.0) | 82.0 (77.0, 87.0) | 83.0 (78.0, 86.0) |

| DLCO (%) predicted | 41.0±15.4 | 41.4±15.4 | 40.7±15.4 |

| DLCO not performed | 54 (9.6) | 23 (8.2) | 31 (11.0) |

| 6MWD (m) | 366 (262, 445) | 370 (257, 447) | 357 (268, 442) |

| Surgical lung biopsy | 177 (31.5) | 93 (33.1) | 84 (29.9) |

| Antifibrotic therapy* | 330 (58.7) | 156 (55.5) | 174 (61.9) |

| Pirfenidone | 200 (35.6) | 89 (31.7) | 111 (39.5) |

| Nintedanib | 165 (29.4) | 84 (29.9) | 81 (28.8) |

| Exertional hypoxia | 228 (40.6) | 110 (39.1) | 118 (42.0) |

| Prescribed oxygen | 133 (58.3) | 67 (23.8) | 66 (23.5) |

| Observed desaturation† | 95 (41.7) | 45 (16.0) | 50 (17.8) |

| GAP stage‡ | |||

| 1 | 115 (20.5) | 63 (22.4) | 52 (18.5) |

| 2 | 278 (49.5) | 142 (50.5) | 136 (48.4) |

| 3 | 169 (30.1) | 76 (27.0) | 93 (33.1) |

Data presented as mean±SD, median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) or n (%).

*Antifibrotic therapy for at least 6 months (some patients transitioned between therapies).

†Observed desaturation during 6 min walk test in the absence of a prior oxygen prescription.

‡GAP stage as classified by the original GAP index proposed and validated by Ley et al. 5

DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; FVC, forced vital capacity; GAP, gender-age-physiology; 6MWD, 6 min walk test distance; OSA, obstructive sleep apneoa.

The median age of the cohort was 72 years (IQR: 66, 77) and 129 patients (23%) were women. Mean FVC% predicted and DLCO% predicted were 65.6±19.1 and 41.0±15.4, respectively. Median 6MWD was 366 m (IQR: 262, 445) and a total of 228 patients (40.6%) exhibited exertional hypoxia. Median follow-up was 1.7 years (0.01–3) during which 163 deaths and 55 lung transplantations occurred.

External cohort characteristics

A total of 108 patients were diagnosed with IPF during the study period at the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou. All patients were included in the final cohort and baseline characteristics are included in table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of all patients in the external cohort

| N=108 | |

| Age (years) | 73 (68, 78) |

| Gender, women | 20 (18.5) |

| Race, non-white | 29 (26.9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.1±3.2 |

| Comorbid disease | |

| Smoking status ever | 76 (70.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (21.3) |

| Hypertension | 42 (38.9) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 44 (40.7) |

| Severe OSA | 17 (15.7) |

| Lung cancer | 4 (3.7) |

| Measures of IPF severity and management considerations | |

| FVC (%) predicted | 81.0±19.5 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 83.0 (79.0, 86.0) |

| DLCO (%) predicted | 47.4±15.7 |

| DLCO not performed | 3 (2.8) |

| 6MWD (m) | 473 (430, 559) |

| Surgical lung biopsy | 21 (19.4) |

| Antifibrotic therapy* | 67 (62.0) |

| Pirfenidone | 32 (29.6) |

| Nintedanib | 50 (46.3) |

| Exertional hypoxia | 45 (42.1) |

| Prescribed oxygen | 36 (33.3) |

| Observed desaturation† | 9 (8.3) |

| GAP stage‡ | |

| 1 | 43 (39.8) |

| 2 | 49 (45.4) |

| 3 | 16 (14.8) |

Data presented as mean±SD, median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) or n (%).

Most patients in this cohort were classified by the GAP index as having stage I (39.8%) or stage II (45.4%) disease.

*Antifibrotic therapy for at least 6 months (some patients transitioned between therapies).

†Observed desaturation during 6 min walk test in the absence of a prior oxygen prescription.

‡GAP stage as classified by the original GAP index proposed and validated by Ley et al. 5

DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GAP, gender-age-physiology; 6MWD, 6 min walk distance.

Original GAP index

The original GAP index had a C-statistic of 0.676 (95% CI 0.635 to 0.717) when applied to our cohort. Calibration of the staging system of the original GAP index was evaluated by comparing previously published predicted mortality to that observed in our cohort.5 The GAP index consistently overestimated mortality. Overestimated mortality (and thus, poor model calibration) was especially problematic for those patients classified as having ‘stage I’ disease (table 3).

Table 3.

Predicted versus observed mortality in the entire cohort based on original GAP index

| Year | Patients (N) | Predicted mortality* (%) | Observed mortality† (%) | Ratio‡ |

| Stage I§ | ||||

| 1 | 96 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 0.34 |

| 2 | 68 | 10.9 | 5.6 | 0.51 |

| 3 | 50 | 16.3 | 12.0 | 0.74 |

| Stage II§ | ||||

| 1 | 207 | 16.2 | 12.8 | 0.79 |

| 2 | 131 | 29.9 | 25.9 | 0.87 |

| 3 | 85 | 42.1 | 37.5 | 0.89 |

| Stage III§ | ||||

| 1 | 94 | 39.2 | 30.7 | 0.78 |

| 2 | 55 | 62.1 | 45.7 | 0.74 |

| 3 | 30 | 76.8 | 60.6 | 0.79 |

New predictors and mortality

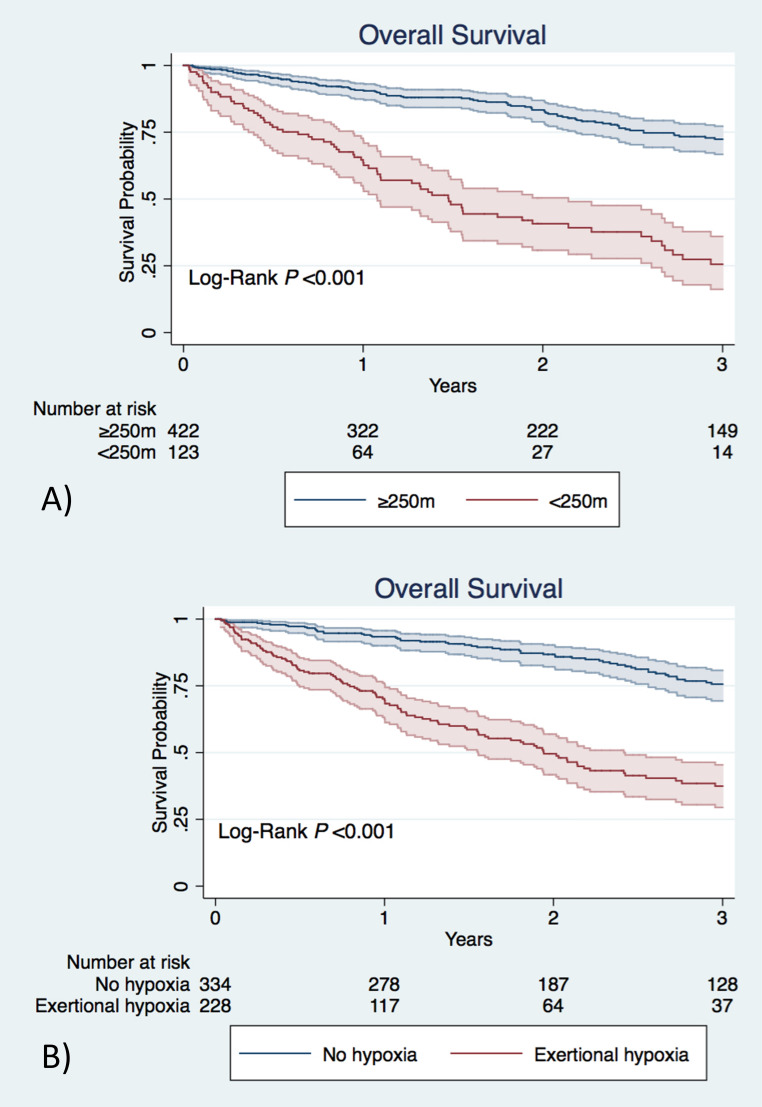

6MWD <250 m and exertional hypoxia were associated with mortality in the entire cohort (HR 4.43, 95% CI 3.21 to 6.10 and HR 4.11, 95% CI 2.97 to 5.68, respectively) (figure 1). The original GAP index, 6MWD and exertional hypoxia were all associated with mortality in univariate analysis of the derivation cohort.

Figure 1.

(A) Overall survival from time of pulmonary function testing based on distance ambulated during 6 min walk test. (B) Overall survival from time of pulmonary function testing based on the presence or absence of exertional hypoxia. Shaded regions represent 95% CIs.

In multivariable analysis, all predictors remained independently associated with all-cause mortality. Inability to walk further than 250 m and exertional hypoxia were associated with a greater than twofold and nearly threefold-independent increase in risk of mortality, respectively (table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariable analysis in the derivation set for association of predictors with mortality in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| GAP index | 1.52 (1.31 to 1.76) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.03 to 1.46) | 0.022 |

| Exertional hypoxia | 4.41 (2.80 to 6.94) | <0.001 | 2.92 (1.70 to 4.99) | <0.001 |

| 6MWD<250 m | 4.72 (2.99 to 7.46) | <0.001 | 2.49 (1.49 to 4.16) | <0.001 |

GAP, gender-age-physiology; 6MWD, 6 min walk test distance.

Additive value of new predictors

The ‘base-model’ (the GAP index) and models containing the new predictors were fit in the derivation cohort and their predictive power was then measured in the internal validation cohort. The applied refit GAP index is included in online supplemental table E1. The discriminative value of 6MWD and exertional hypoxia when added to the original and refit base model are provided in table 5.

Table 5.

Additive predictive value of proposed variables compared with the refit GAP index

| Model | C-statistic (95% CI) | Difference in C-statistic compared with GAP* | NRI (%) (95% CI)* | IDIevent (95% CI)* | IDInon-event (95% CI)* | IDI | |

| (95% CI) | P value | ||||||

| Original GAP index | 0.683 (0.624 to 0.742) | −0.018 (−0.046 to 0.034) | 0.208 | −4.0 (−35.1 to 34.4) | −0.003 (−0.005 to 0.012) | −0.001 (−0.001 to 0.003) | −0.004 (−0.005–0.015) |

| Refit GAP index | 0.701 (0.646 to 0.756) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| GAP +6MWD†† | 0.738 (0.686 to 0.789) | 0.037 (0.003 to 0.070) | 0.031 | 46.6 (15.0 to 75.4) | 0.034 (0.005 to 0.083) | 0.007 (0.002 to 0.017) | 0.041 (0.006–0.101) |

| GAP +EH | 0.742 (0.691 to 0.793) | 0.041 (0.004 to 0.078) | 0.031 | 88.5 (51.8 to 108.3) | 0.045 (0.013 to 0.084) | 0.009 (0.003 to 0.018) | 0.055 (0.016–0.100) |

| GAP +6 MWD††+EH | 0.756 (0.706 to 0.806) | 0.055 (0.011 to 0.098) | 0.014 | 61.9 (26.9 to 102.9) | 0.062 (0.026 to 0.119) | 0.012 (0.005 to 0.025) | 0.074 (0.032–0.143) |

| DO-GAP index‡‡ | 0.752 (0.701 to 0.802) | 0.050 (0.004 to 0.097) | 0.035 | 46.1 (19.6 to 66.2) | 0.055 (0.022 to 0.101) | 0.011 (0.004 to 0.022) | 0.066 (0.026–0.122) |

*Improvement comparisons made to the GAP index after refitting original GAP index to the derivation set.

†6MWD included as categorical variable.

‡Model based on point-score index (see study design and methods for further detail).

DO-GAP, distance-oxygen-gender-age-physiology; EH, exertional hypoxia; GAP, gender-age-physiology; IDI, incremental discrimination improvement; 6MWD, 6 min walk test distance; NRI, net reclassification improvement.

thoraxjnl-2021-218440supp001.pdf (492.5KB, pdf)

Notably, the addition of 6MWD and exertional hypoxia together resulted in the largest improvement in discrimination (C-statistic 0.756; 95% CI 0.706 to 0.806, difference in C-statistic compared with the GAP index: 0.055; 95% CI 0.011 to 0.098). Furthermore, this model demonstrated significant risk reclassification improvement as reflected by the NRI (61.9%; 95% CI 26.9% to 102.9%) and IDI (0.074; 95% CI 0.032 to 0.143).

Given the large improvement in discrimination of the combined model, a simple point-score model was constructed based on regression coefficients in the derivation cohort (table 6).

Table 6.

Proposed DO-GAP index and staging system

| Predictor | Category | Points | |

| Distance | 6MWT distance | ||

| ≥250 metres | 0 | ||

| <250 metres | 5 | ||

| Oxygen | No hypoxia | 0 | |

| Exertional hypoxia | 5 | ||

| Gender | Female | 0 | |

| Male | 1 | ||

| Age (years) | ≤60 | 0 | |

| 61–65 | 1 | ||

| >65 | 2 | ||

| Physiology | FVC, % predicted | ||

| >75 | 0 | ||

| 50–75 | 1 | ||

| <50 | 2 | ||

| DLCO, % predicted | |||

| >55 | 0 | ||

| 36–55 | 1 | ||

| ≤35 | 2 | ||

| Cannot perform | 3 | ||

| Total possible points | 18 | ||

| Points | 0–4 | 5–10 | 11–18 |

| Stage | I | II | III |

DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; DO-GAP, distance-oxygen-gender-age-physiology; FVC, forced vital capacity; 6MWT, 6 min walk test distance.

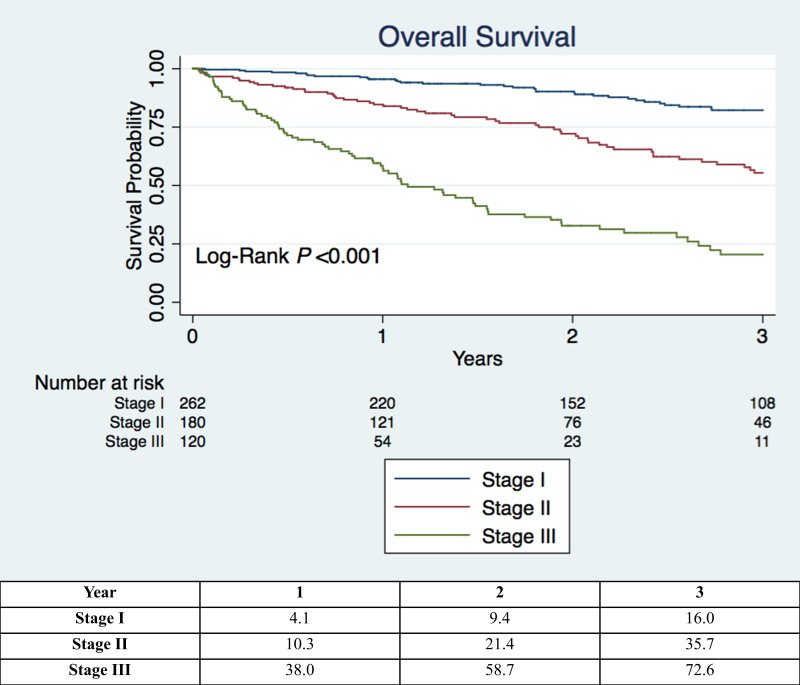

This distance-oxygen-GAP (DO-GAP) index was then tested in the internal validation cohort and demonstrated significantly improved discrimination over the original and refit GAP index. Finally, the DO-GAP index was applied to the external validation cohort and again demonstrated good outcome discrimination (C-statistic 0.780; 95% CI 0.682 to 0.877). Total DO-GAP score points were then grouped into three stages (table 6) and overall survival in the entire internal cohort based on DO-GAP stage is displayed in figure 2. When applied to the internal validation set, the DO-GAP staging system resulted in a stage reclassification from their original GAP stage in 31% of patients (online supplemental table E2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves from time of initial pulmonary function testing based on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis stage as defined by the proposed distance-oxygen-gender-age-physiology (DO-GAP) index. Table beneath figure includes the estimated observed overall mortality (%) by DO-GAP stage in the entire internal cohort.

The calibration of the new score was evaluated in the validation cohorts by comparing observed mortality to the predicted mortality from the derivation cohort. Results of the intercept, slope and joint intercept and slope test were all non-significant, indicative of good overall model calibration in the internal and external validation sets. Though not statistically significant, some miscalibration (overestimation of observed risk) and wide CIs between predicted and observed mortality were evident at the highest predicted event probabilities in the external cohort online supplemental figure E1.

A sensitivity analysis modelling mortality with lung transplantation as a competing risk of death was also performed. The original GAP index, 6MWD and exertional hypoxia all remained similarly associated with mortality in univariate and multivariable analysis compared with the original method using right censoring (online supplemental table E3) and no change to the overall proposed DO-GAP index resulted from this analysis. Furthermore, DO-GAP model performance remained consistent when lung transplantation was treated as a competing risk of death in the internal validation set (C-statistic 0.746; 95% CI 0.697 to 0.796, difference in C-statistic compared with the GAP index: 0.068; 95% CI 0.018 to 0.119) and external validation cohort (C-statistic 0.768; 95% CI 0.664 to 0.873). Calibration, too, remained good overall and visually indistinguishable to that of the right censored model (data not shown to avoid redundancy). Model performance was also evaluated in the subgroup of patients in the internal cohort that received antifibrotic therapy (online supplemental figure E2) and patients diagnosed with IPF within 5 years prior to conclusion of the study. Both the original GAP index and the DO-GAP index performed consistently compared with discrimination in the entire cohort. Difference in discrimination between the DO-GAP index and the GAP index for patients in the internal validation cohort on antifibrotics (N=174) and those evaluated most recently (N=141) both favoured the DO-GAP index, however, these differences were not statistically significant (online supplemental tables E4 and E5). The DO-GAP index again demonstrated significant risk reclassification improvement compared with the GAP index in both subgroups.

Discussion

We assessed the performance of the GAP index in a contemporary cohort of patients treated for IPF. The GAP index provided slightly lower discrimination compared with the original cohort in which it was validated.5 Furthermore, the index was not well calibrated and overestimated mortality, especially in mild and moderate disease. Notably, reduced 6MWD and exertional hypoxia were factors strongly predictive of overall mortality. The addition of these variables to the GAP index significantly improved model discrimination. Finally, we generated, internally, and externally validated an extension of the original GAP index, termed the DO-GAP index, incorporating 6MWD and exertional hypoxia into a simple point-score model. Our new index demonstrated improved discrimination in the internal validation cohort compared with the original and refitted GAP index as well as satisfactory calibration. In addition, it maintained utility in discriminating outcomes when applied to patients with a recent diagnosis of IPF, those treated with antifibrotic therapy and patients with IPF from a geographically distinct external cohort.

IPF is a progressive disease with a prognosis worse than many types of cancer and associated debility that threatens patient independence and quality of life.28 The time of diagnosis has been described as a valuable ‘touchpoint’, a point of patient vulnerability heralding a period of inevitable lifestyle transition.29 The knowledge provided at this encounter, including precise information regarding prognosis, is important in providing usable information to patients and clinicians to plan for future events including the possible need for supplemental oxygen, lung transplantation, consultation of palliative care and ultimate demise.

A number of existing models provide prognostic insight regarding survival in IPF.4–8 Of these models, several has been constructed, which incorporate longitudinal data (factors collected over multiple visits) to predict long-term outcomes.4 18 Though this approach is expected to produce accurate long-term prediction of outcome, it is limited by the need for repeated testing. A subset of these existing models incorporates baseline factors in order to predict prognosis through immediately available objective data.5 6 This approach has the advantage of ease of implementation in clinical practice and allows for sharing of valuable prognostic information to patients during the initial ‘touchpoint’. However, of the available baseline models, the most used, the GAP index, has shortcomings that make its application in clinical practice challenging. Since the development of the original GAP index in 2011, a number of changes in the care of patients with IPF have occurred. First, a large percentage of patients in the original cohort were treated with prednisone, azathioprine and N-acetylcysteine, which current clinical practice guidelines no longer recommend.30 Second, two antifibrotic medications, pirfenidone and nintedanib have emerged as effective therapies for IPF associated with a reduction in the decline of lung function, reduced risk of acute deterioration and possible improved life expectancy.31 Finally, mortality in IPF appears to be decreasing.32 These changes in management and prognosis may explain the observation that the GAP index overestimates mortality in more contemporary cohorts.4 Furthermore, though easy to use, the GAP index may not be predictive of pulmonary function decline over time and may be outperformed as a means of mortality prediction by measures of exercise capacity such as the 6MWD or the need for supplemental oxygen.14 33

The 6MWD is a reliable and reproducible measure of disease status in IPF and can be performed by nearly all patients, even in the presence of severe functional limitations.19 22 34 The test assesses overall functional ability and captures the convergence of multiple influences on exercise capacity including respiratory, cardiovascular, rheumatologic and neurologic contributions.35 Most notably, cardiovascular disease, which is more prevalent in patients with IPF, can directly impact mortality.36 This may be one reason that the addition of the 6MWD to the original GAP score improves its prognostication for all-cause mortality. Furthermore, 6MWD may impart additional prognostic value compared with spirometry data in patients with comorbid obstructive lung disease by identifying impairment that might otherwise be missed by spurious preservation of the FVC.37 Additionally, the 6MWD captures functional impairment imposed by complicating pulmonary hypertension.38 Other investigators have found that the 6MWD added significant prognostic value to an existing longitudinal model for IPF, and this model was also updated to include this factor.18 Likewise, exertional hypoxia is an objective measure of disease severity that has been associated with mortality in patients with IPF.10 39–41 We demonstrated that the incorporation of these two measures of exercise capacity into the original GAP index significantly improved the predictive value of the model. The relative improvement in C-statistic of the DO-GAP index compared with the original and refitted GAP index of 0.068 and 0.050, respectively, observed in the internal validation set is consistent with a large overall improvement in model discrimination.42

Our study has a few limitations. The new scoring system was developed through retrospective evaluation of records from a single tertiary care centre with the possibility of referral bias. Although our centre has an advanced lung disease programme and also houses a lung transplant programme, we evaluate patients with IPF across a wide range of disease severity. Indeed, the mean FVC of the cohort (65.6%) is not too different from that reported in phase 3 IPF clinical trials that generally included patients with mild to moderate disease.43 In addition, model performance was consistent when applied to an external, geographically distinct cohort from a hospital without an advanced lung disease service.

Several testing limitations are also important to recognise. First, during the study time period, reference values for pulmonary function testing were introduced and updated. These updated reference equations have generally been found to produce concordant results, however, differences in per cent-predicted lung function based on extreme height or age or under-represented ethnicity could not be accounted for in our results.44 The performance of a DLCO manoeuvre was protocolised for all patients at their initial visit. If DLCO was unavailable, then this was assumed related to their respiratory limitation; however, in a very small minority of cases, this absence may have been due to other factors. Furthermore, both centres involved in this study are located at sea level and exertional hypoxia may be identified earlier in the disease course at sites at higher elevations. It is important to note that our model includes ‘exertional hypoxia’ rather than supplemental oxygen use, since we were unable to account for compliance with this. Both of these caveats may have introduced bias in the inclusion of exertional hypoxia in our risk prediction model. Furthermore, we evaluated combinations of predictors using the GAP index as a ‘base-model’. The model in its current form requires that all components of the risk score be available to accurately assess risk. Other potentially useful predictors including radiographic abnormalities and serum biomarkers were not evaluated. This approach was chosen to maximise simplicity, practicality, reproducibility and statistical power and is similar to that of other investigators who have sought to improve on original models in IPF.4 18 We chose not to alter the categorical thresholds in the original GAP index and it is possible that modifying one or more of the GAP index predictors could have improved its final performance in our more contemporary IPF cohort. Likewise, in their original work, Ley et al reported a ‘GAP calculator’ which provided risk estimation based on a fully specified continuous model.5 It is likely that such a continuous model would provide more precise risk estimation compared with a point-score index. However, as our goal was to derive a model suited for implementation in clinical practice, we chose not to explore this further. Finally, while necessary sample size for model development was achieved, the external cohort and subgroup sample sizes were small. Specifically, though the proportion of women in our sample likely reflects the epidemiology of IPF, the overall number of women, the prevalence of lung cancer and the proportion of patients administered antifibrotics were low, which may limit generalisability of our results. Furthermore, though the prediction model was well calibrated overall, a visual trend towards miscalibration with lower observed events and wide CIs at the highest predicted event probabilities were appreciated in the external cohort. This likely reflects the small number of high-risk patients in this subset of the external validation cohort. Thus, despite validation in a randomly derived internal subset of patients as well as an external cohort, our DO-GAP index should be further evaluated in other larger cohorts of patients with IPF. Although the DO-GAP index performed better than the original GAP index in patients on antifibrotics and in the more recent era, this improvement in discrimination was not statistically significant, which likely reflects the smaller size of these subgroups.

Conclusion

In summary, we assessed the utility of the GAP index in a modern real-world cohort of patients with IPF. We found that the original index was not well calibrated to predict outcomes observed in our cohort. 6MWD and exertional hypoxia were significant prognostic factors strongly associated with overall survival. These prognostic factors were then combined into a new model, the DO-GAP index, which demonstrated improved outcome discrimination and calibration compared with the original GAP index.

Footnotes

Contributors: AC and SDN take full responsibility for the content of this paper and act as guarantors for the data. AC, JP, CSK, and SDN conceived the study design. JP and SV were responsible for data acquisition. AC performed the data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings, critically revised the paper for intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SDN is a consultant and is on the speakers bureau for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche and United Therapeutics. The other authors have no conflicts of interest or disclosures pertinent to this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB Numbers U20-03-3956 and CEPRO2021-029) at Inova Fairfax Hospital and Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board at both institutions in part due to the retrospective study design and low risk for patient identification during performance of this research.

References

- 1. Khor YH, Ng Y, Barnes H, et al. Prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis without anti-fibrotic therapy: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29:190158. 10.1183/16000617.0158-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaunisto J, Salomaa E-R, Hodgson U, et al. Demographics and survival of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the FinnishIPF registry. ERJ Open Res 2019;5:00170-2018. 10.1183/23120541.00170-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tran T, Šterclová M, Mogulkoc N, et al. The European MultiPartner IPF registry (Empire): validating long-term prognostic factors in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2020;21:11. 10.1186/s12931-019-1271-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ley B, Bradford WZ, Weycker D, et al. Unified baseline and longitudinal mortality prediction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2015;45:1374–81. 10.1183/09031936.00146314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ley B, Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, et al. A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:684–91. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wells AU, Desai SR, Rubens MB, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a composite physiologic index derived from disease extent observed by computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:962–9. 10.1164/rccm.2111053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. du Bois RM, Weycker D, Albera C, et al. Ascertainment of individual risk of mortality for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:459–66. 10.1164/rccm.201011-1790OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mura M, Porretta MA, Bargagli E, et al. Predicting survival in newly diagnosed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a 3-year prospective study. Eur Respir J 2012;40:101–9. 10.1183/09031936.00106011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee SH, Park JS, Kim SY, et al. Comparison of CPI and GAP models in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep 2018;8:4784. 10.1038/s41598-018-23073-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharp C, Adamali HI, Millar AB. A comparison of published multidimensional indices to predict outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res 2017;3. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00096-2016. [Epub ahead of print: 14 03 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kärkkäinen M, Kettunen H-P, Nurmi H, et al. Comparison of disease progression subgroups in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med 2019;19:228. 10.1186/s12890-019-0996-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robbie H, Daccord C, Chua F, et al. Evaluating disease severity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2017;26:170051. 10.1183/16000617.0051-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pastre J, Barnett S, Ksovreli I, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients with severe physiologic impairment: characteristics and outcomes. Respir Res 2021;22:5. 10.1186/s12931-020-01600-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pesonen I, Gao J, Kalafatis D. Six-minute walking test outweighs other predictors of mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A real-life study from the Swedish IPF registry. Respiratory Medicine: X 2020;2:100017. 10.1016/j.yrmex.2020.100017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788–824. 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16., American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society . American thoracic Society/European respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. this joint statement of the American thoracic Society (ATS), and the European respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277–304. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:e44–68. 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. du Bois RM, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. 6-minute walk distance is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1421–9. 10.1183/09031936.00131813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. RMd B, Weycker D, Albera C, et al. Six-minute-walk test in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:1231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacobs SS, Krishnan JA, Lederer DJ, et al. Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease. An official American thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:e121–41. 10.1164/rccm.202009-3608ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American thoracic Society and European respiratory Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:e70–88. 10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European respiratory Society/American thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428–46. 10.1183/09031936.00150314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strongman H, Kausar I, Maher TM. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the UK. Adv Ther 2018;35:724–36. 10.1007/s12325-018-0693-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Riley RD, Snell KI, Ensor J, et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II - binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med 2019;38:1276–96. 10.1002/sim.7992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newson RB. Comparing the Predictive Powers of Survival Models Using Harrell’s C or Somers’ D. Stata J 2010;10:339–58. 10.1177/1536867X1001000303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med 2011;30:11–21. 10.1002/sim.4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Royston P. Tools for checking calibration of a Cox model in external validation: approach based on individual event probabilities. Stata J 2014;14:738–55. 10.1177/1536867X1401400403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vancheri C, Failla M, Crimi N, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disease with similarities and links to cancer biology. Eur Respir J 2010;35:496–504. 10.1183/09031936.00077309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Swigris JJ. Transitions and touchpoints in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir Res 2018;5:e000317. 10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:e3–19. 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maher TM, Strek ME. Antifibrotic therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: time to treat. Respir Res 2019;20:205. 10.1186/s12931-019-1161-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jeganathan N, Smith RA, Sathananthan M. Mortality trends of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States from 2004 through 2017. Chest 2021;159:228–38. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salisbury ML, Xia M, Zhou Y, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Gender-Age-Physiology index stage for predicting future lung function decline. Chest 2016;149:491–8. 10.1378/chest.15-0530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holland AE, Hill CJ, Dowman L, et al. Short- and long-term reliability of the 6-minute walk test in people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Care 2018;63:994–1001. 10.4187/respcare.05875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown AW, Nathan SD. The value and application of the 6-Minute-Walk test in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018;15:3–10. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-244FR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nathan SD, Basavaraj A, Reichner C, et al. Prevalence and impact of coronary artery disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2010;104:1035–41. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eaton T, Young P, Milne D, et al. Six-minute walk, maximal exercise tests: reproducibility in fibrotic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1150–7. 10.1164/rccm.200405-578OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1023–30. 10.1164/rccm.200510-1668OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, et al. A simple assessment of dyspnoea as a prognostic indicator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1067–72. 10.1183/09031936.00152609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kondoh Y, Taniguchi H, Kataoka K, et al. Disease severity staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Japan. Respirology 2017;22:1609–14. 10.1111/resp.13138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takei R, Yamano Y, Kataoka K, et al. Pulse oximetry saturation can predict prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Investig 2020;58:190–5. 10.1016/j.resinv.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, D'Agostino RB, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72. discussion 207-12. 10.1002/sim.2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. King TE, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2083–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Linares-Perdomo O, Hegewald M, Collingridge DS, et al. Comparison of NHANES III and ERS/GLI 12 for airway obstruction classification and severity. Eur Respir J 2016;48:133–41. 10.1183/13993003.01711-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2021-218440supp001.pdf (492.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.