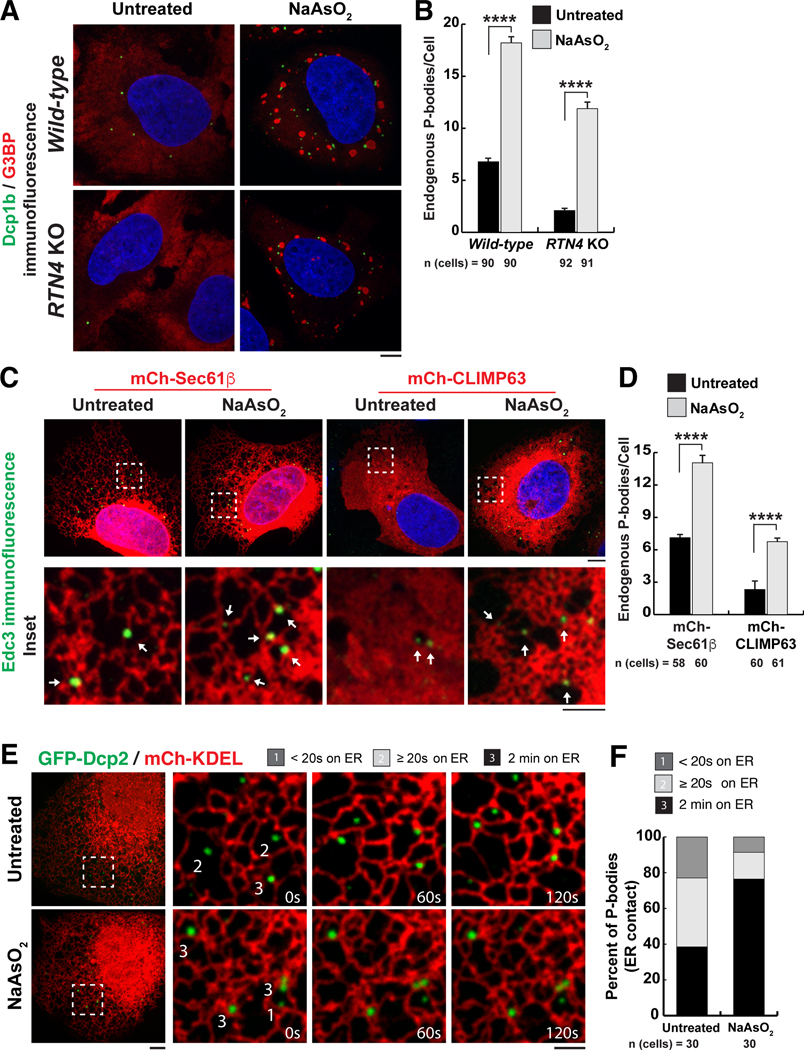

Fig. 4. The relationship between PB biogenesis, ER shape, and oxidative stress–induced mRNA translation inhibition.

(A) Representative images of Dcp1b (PB marker, green) and G3BP (stress granule marker, red) IF studies were performed in wild-type and RTN4 KO U-2 OS cells treated with 0.5 mM NaAsO2 for 1 hour. Blue indicates the nucleus stained by Hoechst. (B) The mean numbers of endogenous PBs were quantified from three biological replicates. (C) Representative images of Edc3 IF studies performed in U-2 OS cells transiently transfected with mCh-Sec61β or mCh-CLIMP63 treated with 0.5 mM NaAsO2 for 1 hour. Arrows within insets highlight PBs that overlap with domains of high ER membrane curvature. (D) The mean numbers of endogenous PBs were quantified from three biological replicates in U-2 OS cells exogenously expressing mCh-Sec61β or mCh-CLIMP63 that were either untreated or treated with NaAsO2. (E and F) Representative merged images of U-2 OS cells exogenously expressing GFP-Dcp2 and mCh-KDEL to label PBs and the ER in live cells, respectively (E). Insets show movement of the two organelles through space and time over a 2-min time-lapse movie with frames captured every 5 s. PBs were binned as in Fig. 1C. Cells were imaged for each condition from three biological replicates and quantified for the degree of association between the ER and PBs (F). In (B) and (D), statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons, and error bars indicate SEM; ****P < 0.0001. In (A), (C), and (E), scale bars are 5 and 2 μm in full cell and inset images, respectively.