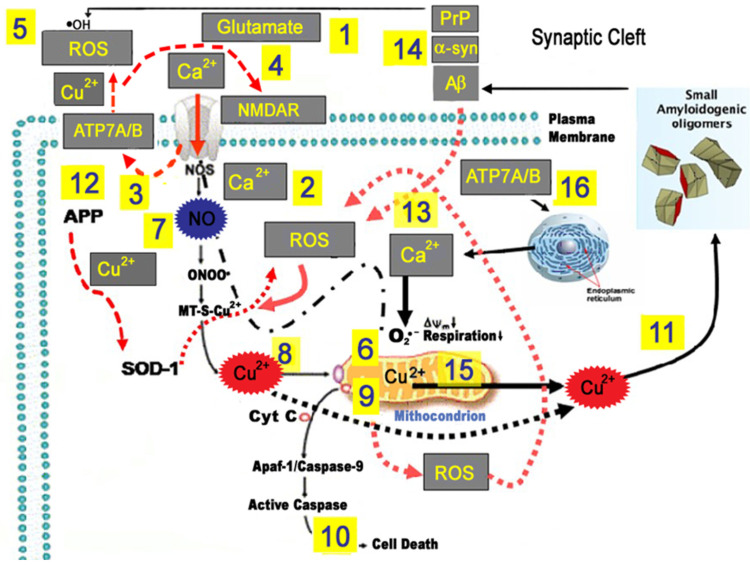

Figure 3.

Model of Beta amyloid (Aβ), glutamate, oxidative stress, and ionic dyshomeostasis in neurodegenerative processes associated with Traumatic Brian Injury (TBI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Aβ, alpha synuclein (α-syn), and hyper-phosphorylated Tau are among the most frequently reported molecules upregulated in TBI and are also closely related to AD. Experimental models of TBI [58] show that Cu concentrations were increased in the ipsilateral cortex adjacent, but not closest, to the impact zone only 28 days after the injury, and it may be cause for concern in relation to the potential chronic oxidative stress toxicity based on Cu abnormal metabolism, as has been observed in neurodegenerative disorders and more specifically for AD. The model proposed to highlight the main Cu toxic mechanisms that can be triggered by TBI in the long term and in AD. In a complex scenario, Aβ, oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and Cu2+ dyshomeostasis act in concert to promote synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. Upon the production of excessive glutamate levels (1), Ca2+ ions enter the cell through the NMDA receptor (2) and (3) induce Cu-ATPase7A/B (ATP7A/B) translocation at synapses where vesicular Cu is released in the synaptic cleft. The released Cu2+ (in concentrations up to 100 µmol/L) may inhibit the NMDA receptor, thereby protecting neurons from glutamatergic excitotoxicity (4), or catalyze Fenton-type and Haber–Weiss reactions, thereby generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) (5). Enhanced ROS generation can damage proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, eventually leading to cell death (5). Ca2+ overload can increase superoxide anion (O2•−) production from mitochondria (6), and nitric oxide (NO) generation via Ca2+-dependent activation of NO synthase (NOS) (7). Reactive oxygen and nitrosative (RNS) species mobilize Cu2+ from metallothionein 3 (MT-3) (8), leading to increased intracellular toxic Cu2+ concentrations (9) and promoting mitochondrial dysfunction, as well as release of pro-apoptotic factors (10). ROS-driven Cu2+ mobilization can further aggravate oxidative stress and initiate Aβ oligomerization (11). Altered trafficking of APP and/or elevated Aβ oligomer secretion can generate an intracellular Cu2+ deficiency, thereby causing oxidative stress by the loss of SOD-1 function (12). Aβ, α-synuclein, and PrP increased after TBI can modulate neurotransmission as [Cu2+] buffers within the synaptic cleft or amplify the vicious cycle by increasing oxidative stress (13). Furthermore, glutamate-driven mitochondrial Ca2+ overload can mobilize Cu2+ from these organelles (14). Excess Non-Cp Cu in the bloodstream is a source for the buildup of labile Cu2+ into the intermembrane space of mitochondria (15), promoting the ATPase7A/B translocation of Cu2+ into vesicles of the trans-Golgi network and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (16). These processes, working intracellularly at the level of synaptic spines, in the synaptic cleft, and in the neurovascular unit (ref. [8]), can facilitate synaptic dysfunction, neuronal deafferentation, and ultimately brain cell death.