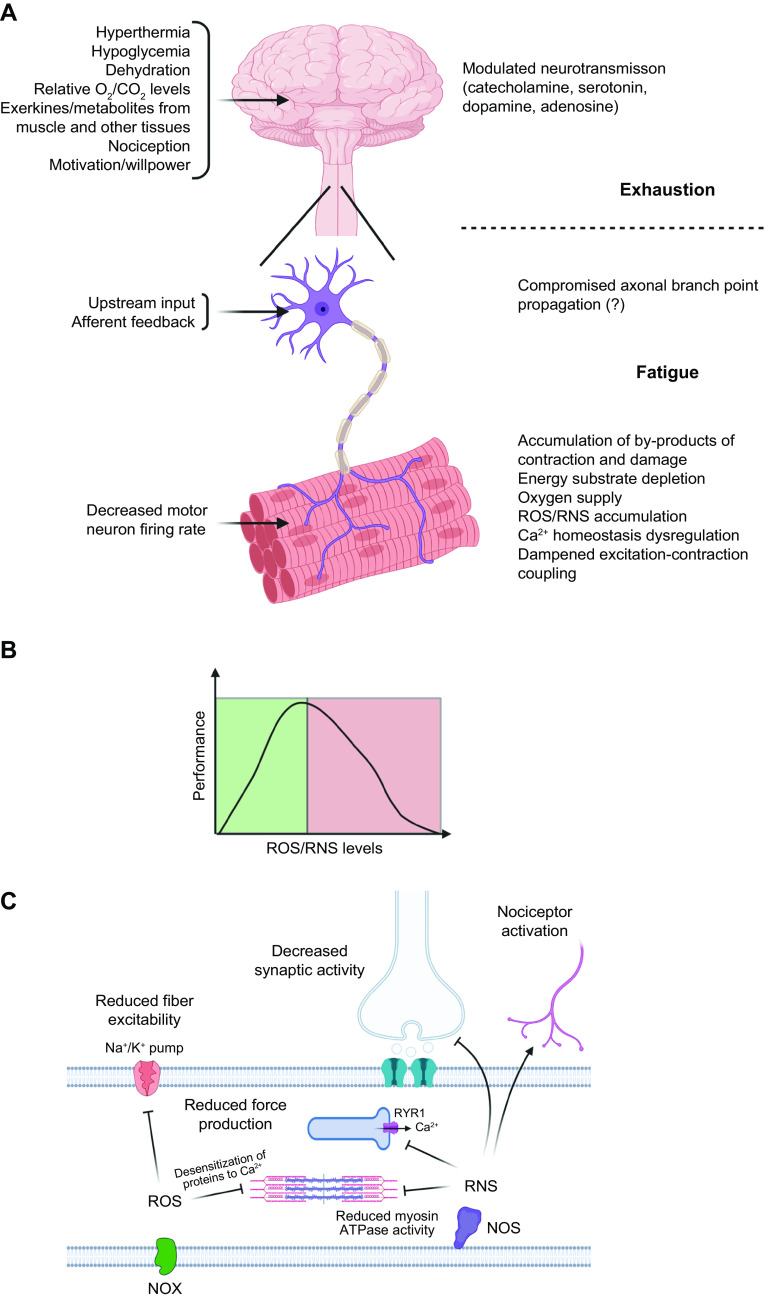

FIGURE 16.

Exhaustion and muscle fatigue. A: central and peripheral contributors to exhaustion (volitional) and fatigue (involuntary). Altered neurotransmission in the brain ensures protection of this and other organs from hyperthermia, hypoglycemia, dehydration, shifted O2/CO2 levels, and further potentially detrimental processes in exercise. To a limited extent, these effects can be overcome by willpower and motivation. Peripheral factors of fatigue involve the motor neuron and muscle fibers. Although impairments in action potential propagation and neuromuscular junction transmission seem minor in healthy individuals, input from upstream brain regions and afferent feedback modulate motor neuron firing rate. Muscle-intrinsic contractility is affected by energy substrate and oxygen availability, accumulation of by-products of contraction and damage, elevation of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen (RNS) species, a dampening of excitation-contraction coupling including the Na+-K+ pump, and intramyocellular Ca2+ homeostasis. B: concentration-dependent, biphasic bell-shaped effect of ROS and RNS on muscle performance. During contractions, ROS and RNS sustain and enhance contractile activity. However, once levels exceed a poorly defined threshold, a different set of processes is engaged that limits performance. C: exceeding a certain concentration, ROS and RNS contribute to muscle fatigue by affecting fiber excitability and contractility, synaptic activation, and nociception. A modulation of intramyocellular Ca2+ homeostasis thereby plays a central role. Putatively, this “rheostat” helps to avoid overexertion and to minimize muscle tissue damage. NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NOX, NADPH oxidase; RYR1, ryanodine receptor 1. Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.