Abstract

Rationale

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is recommended by guidelines; however, few patients participate, and rates vary between hospitals.

Objectives

To identify contextual factors and strategies that may promote participation in PR after hospitalization for COPD.

Methods

Using a positive-deviance approach, we calculated hospital-specific rates of PR after hospitalization for COPD among a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries. At a purposive sample of high-performing and innovative hospitals in the United States, we conducted in-depth interviews with key stakeholders. We defined high-performing hospitals as having a PR rate above the 95th percentile, at least 6.58%. To learn from hospitals that demonstrated a commitment to improving rates of PR, regardless of PR rates after discharge, we identified innovative hospitals on the basis of a review of American Thoracic Society conference research presentations from prior years. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Using a directed content analysis approach, transcripts were coded iteratively to identify themes.

Results

Interviews were conducted with 38 stakeholders at nine hospitals (seven high-performers and two innovators). Hospitals were diverse regarding size, teaching status, PR program characteristics, and geographic location. Participants included PR medical directors, PR managers, respiratory therapists, inpatient and outpatient providers, and others. We found that high-performing hospitals were broadly focused on improving care for patients with COPD, and several had recently implemented new initiatives to reduce rehospitalizations after admission for COPD in response to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services/Medicare’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. Innovative and high-performing hospitals had systems in place to identify patients with COPD that enabled them to provide patient education and targeted discharge planning. Strategies took several forms, including the use of a COPD navigator or educator. In addition, we found that high-performing hospitals reported effective interprofessional and patient communication, had clinical champions or external change agents, and received support from hospital leadership. Specific strategies to promote PR included education of referring providers, education of patients to increase awareness of PR and its benefits, and direct assistance in overcoming barriers.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that successful efforts to increase participation in PR may be most effective when part of a larger strategy to improve outcomes for patients with COPD. Further research is necessary to test the generalizability of our findings.

Keywords: pulmonary rehabilitation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, positive deviance, qualitative, Medicare

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects nearly 16 million individuals in the United States and is the country’s sixth leading cause of death (1, 2). Approximately 700,000 patients are hospitalized for exacerbations of COPD each year, and more than 1 in 5 patients will be readmitted within 30 days of discharge (3). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions have been shown to reduce symptoms, as well as the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and to improve health status and quality of life (4).

There is strong evidence that pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) improves exercise capacity and health-related quality of life in patients with COPD (5–9). In addition, PR may prevent readmission and improve survival (10). PR appears to be particularly beneficial after a hospitalization, a period when the risk of further deconditioning is high (11, 12). Although current guidelines recommend that patients hospitalized for COPD initiate PR within 3–4 weeks of discharge (13), prior research by this study team found that only 1.9% of Medicare beneficiaries participated in PR within 6 months of discharge (14).

The low rates of PR uptake highlight the need for research to identify strategies to increase patient participation. Prior research has explored barriers and facilitators among patients with stable disease (15, 16). Barriers to participation include those at the policy, hospital, physician, and patient levels (17–19). A handful of studies have tested interventions to increase participation in PR among patients with stable COPD; however, little is known about how to promote participation after an exacerbation (20). The goal of this study was to identify contextual factors and strategies employed by health systems that achieve relatively high rates of participation in PR after hospitalization.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

A positive deviance approach focuses on exceptional organizations in real-world settings and seeks to learn from them to generate hypotheses about their success (21). This qualitative study is part of a multistage process and is intended to inform the subsequent stage of the positive deviance research cycle, a national survey of hospital-affiliated PR programs that will test the hypotheses generated by the findings presented here.

We conducted in-depth interviews of clinical and administrative staff during site visits at a sample of hospitals that achieved superior performance or had demonstrated innovative practices with respect to patient participation in PR after hospitalization for COPD.

Hospital selection

To identify high-performing hospitals, we used Medicare claims data to identify all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for COPD between January 2014 and September 2015. We then identified patients who received PR within 90 days of discharge from their index hospitalization and calculated hospital-specific rates of PR after hospitalization. (For full details on how we defined the patient cohort, see Spitzer and colleagues [14].) Unadjusted hospital-level rates of PR receipt within 90 days of discharge ranged from 0.00 to 100 (interquartile range: 0–2.3). We defined high-performing hospitals as having a rate above the 95th percentile, at least 6.58%. To achieve a diverse sample of programs in the United States, we used purposive sampling to select high-performing hospitals that varied on the basis of region, geographic location, teaching status, number of beds, and whether the hospital had a lung transplant program. (Patients undergoing lung transplants are required to participate in PR, and these hospitals may have more resourced programs.) To learn from hospitals that demonstrated a commitment to improving rates of PR, regardless of their rate in 2014–2015, we reviewed American Thoracic Society conference presentations from prior years and selected those affiliated with investigators who had conducted research on strategies to increase participation in PR.

Data Collection

Between July 2019 and February 2020, we conducted seven in-person site visits. In addition, because of travel restrictions imposed by coronavirus disease (COVID-19), we conducted two virtual site visits in June 2020 for a total of nine visits, seven high performers and two innovators. The purpose of site visits, which was known to study participants, was to understand the process by which patients hospitalized with a COPD exacerbation are enrolled in PR after discharge and to identify the contextual factors and strategies used to promote participation.

The interview instrument was informed by existing literature and the CFIR (Consolidated Framework Implementation Research) (22). The framework provides a taxonomy of constructs that may influence the implementation of complex programs. The five key domains are inner setting, outer setting, individuals involved, process, and intervention. We ensured that the instrument covered all the domains of the CFIR. The specific interview topics included the role of the interviewee within the PR program or hospital, the role of PR within the hospital and care for patients with COPD, the process of referring patients to PR, strategies to increase participation, and barriers to increasing participation in PR. Questions were open-ended, and interviews were semistructured. The interview guide collected the interview subjects’ demographics: job title, degree, years in current position, and data required for reporting to the National Institutes of Health (gender, race, and ethnicity). The interview guide was pilot tested with the clinical staff at Baystate Medical Center.

The site visit teams consisted of one clinician (V.M.P.-P., P.K.L., M.S.S., or R.L.Z.), the research coordinator (K.A.S.), and the research assistant (B.H.). Outreach to PR centers was conducted over mail, phone, and email to identify the appropriate contact person at each site, usually the medical director or PR program manager. We conducted recruitment region by region, starting in the Northeast and moving across the country from east to west. Working with the contact person, the research team identified key individuals to interview. We attempted to interview clinicians with knowledge of inpatient COPD care and PR at each site, such as medical directors of PR, pulmonologists, hospitalists, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, nurses, social workers, and navigators. Interviewees were offered a $50 gift card for completing the interview. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. The research coordinator (K.A.S.) conducted all interviews. Whenever possible, interviews occurred in person at the hospital or PR site in a private room. In several instances, interviews with providers who were not available during the site visit were conducted by phone. Two virtual site visits were conducted over WebEx. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The research team took field notes documenting observations of the hospital and PR environment. During site visits, materials such as patient education flyers were also collected. Interview transcripts, field notes, and print materials were entered into NVivo 12 for organization and coding.

Data Analysis

The qualitative coding team consisted of K.M., K.A.S., and K.B., with the full study team meeting on a regular basis to review codes and definitions. The site-visit data were analyzed using a directed content analysis approach (23); an initial codebook was derived from existing literature on barriers and facilitators to participation in PR, the interview guide, and the CFIR. Coding was iterative, and emergent codes and definitions were developed by the coding team and shared with the full study team. K.A.S. and K.B. coded all interview transcripts; the first interview at each site was coded independently by K.A.S. and K.B. to check for agreement on code definitions. Subsequently, K.B. coded each transcript independently, and K.S. reviewed the coded transcript to ensure agreement and accuracy. Any disagreements in coding were discussed by the qualitative team until consensus was achieved. Although the COVID-19 pandemic halted site visits prematurely, the coding team did find that coding saturation occurred.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Baystate Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

Hospitals and Participants

We invited 17 hospitals to participate in our study; 5 declined and 3 were nonresponsive. In total, we conducted site visits at nine hospitals. They were in urban, suburban, and rural locations; four were teaching hospitals, the total number of hospital beds ranged from 25 to 1,514, and four had lung transplant programs.

The PR programs were most frequently located in the hospital or on campus, though two were located offsite in outpatient settings. Six programs shared space with cardiac rehabilitation. PR programs varied in how long they had been in operation, the schedules they offered, the method of admissions (e.g., rolling or cohort), and whether they required patients to quit smoking before enrollment (Table 1, program-level characteristics). Because our outreach process moved from east to west, no hospitals from the West were included in our study because we were conducting outreach to Midwestern and Western hospitals in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic placed unprecedented strain on hospitals, especially pulmonologists and respiratory therapists.

Table 1.

Site and interviewee characteristics

| Characteristic | High Performers |

Innovators |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP01 | HP03 | HP04 | HP07 | HP08 | HP10 | HP13 | IN05 | IN12 | |

| Region | Northeast | Northeast | Northeast | South | South | South | Midwest | Northeast | South |

| Beds (mean, 680; range: 25–1,541) | Small | Small | Large | Large | Small | Small | Large | Large | Large |

| Teaching | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Urban/rural/suburban | Suburban | Suburban | Urban | Urban | Rural | Suburban | Urban | Urban | Urban |

| Lung transplant program | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Location of PR gym | In hospital | In hospital | On campus | Offsite | In hospital | In hospital | On campus | On campus | Offsite |

| Interviewees, n | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Medical director | X | — | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| PR director | X | X | — | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Administrator | X | — | — | X | — | — | — | — | — |

| Respiratory therapist | X | — | X | X | X | X | X | — | X |

| Inpatient provider | — | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | X |

| Outpatient provider | — | X | — | X | X | — | X | — | — |

| Case manager | — | — | — | — | — | X | — | — | — |

| COPD educator or navigator | — | — | X | X | — | — | — | — | X |

| Other | — | X | — | — | — | X | — | — | — |

| Virtual | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HP = high performer; IN = innovator; PR = pulmonary rehabilitation.

In total, 38 clinicians were interviewed across nine sites (Table 1).

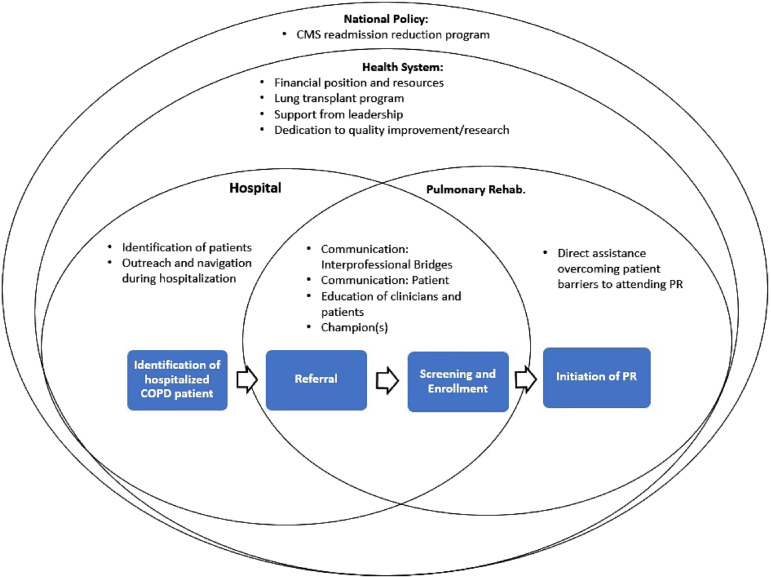

The findings from the site visits were mapped to the CFIR constructs (Figure 1) and are presented below, organized by domain and construct. Note that not all the constructs in the CFIR were connected to themes. For exemplary quotes corresponding to each theme, please see Appendix B in the data supplement.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing rates of pulmonary rehabilitation. CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PR = pulmonary rehabilitation.

Outer Setting

Response to CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) hospital readmission reduction program (external policy and incentives)

The focus on reducing 30-day readmission rates in response to the CMS HRRP (Hospital Readmission and Reduction Program) came up in all site visits. PR was frequently cited as part of a broader strategy to reduce readmissions, though not necessarily within the 30-day timeframe, as it is impossible for patients to complete a full course of PR within 30 days of being discharged. However, PR providers did believe the program helped prevent readmission.

The focus on reducing readmissions encouraged innovations that appeared to indirectly improve awareness of and participation in PR. Other strategies directly related to efforts to avoid financial penalties from HRRP included: creating systematic methods for tracking patients hospitalized with COPD and creating new positions to help patients navigate the transition from the hospital to home, such as COPD navigators. Several of the clinicians tasked with reducing readmissions cited PR as one strategy to support this goal.

Inner Setting

Identification of hospitalized patients (access to knowledge and information)

Systematically identifying potentially eligible patients was an important component of improving referrals to PR. This was especially true in large hospitals with high volumes of patients with COPD. In some instances, a daily dashboard of patients hospitalized with COPD was reviewed by a navigator or nurse who prioritized patients for outreach. In one instance, a designated team member would print out a list of all hospitalized patients and manually highlight patients potentially eligible for PR. More important than the technology was the presence of a regular and systematic process for identifying patients and a designated person to follow up. Even with these processes in place, there was the challenge of confirming the COPD diagnosis. Frequently patients with an admitting diagnosis of COPD would not meet the full diagnostic criteria; for example, they may not have had confirmatory pulmonary function tests.

Communication: interprofessional bridges (networks and communication)

Interprofessional communication challenges varied depending on the size of the hospital, but the presence of clinicians who bridged the inpatient and outpatient settings seemed to facilitate interprofessional communication about PR. For example, in small hospitals, awareness of PR was facilitated by proximity to the PR program and regular interaction between clinicians.

In larger hospitals, communication was facilitated by individuals who bridged inpatient and outpatient settings. In one large hospital, there was no PR staff who worked in both settings, but there was a collaboration among cardiac rehabilitation and PR staff and multidisciplinary rounds that facilitated communication.

Some hospitals had roles that intentionally bridged inpatient and outpatient settings to assist patients transitioning from the hospital to home. For example, three hospitals had COPD navigators, nurses, or respiratory therapists who worked with patients in the hospital and then followed up by phone or text message after discharge. These clinicians were not employed by PR, but they were knowledgeable of PR and would advocate for enrollment in PR when appropriate.

Communication: patient (culture)

PR clinicians emphasized the importance of persistent patient-centered communication. Several stressed that they formed personal connections with patients through repeated encounters in which they encouraged PR participation and provided COPD education.

Financial position and resources (relative priority and available resources)

The financial challenge of running a PR program was frequently noted, especially regarding Medicare reimbursement. Program directors noted that PR does not make money for hospital systems, but there was a strong belief that PR reduced costs to the healthcare system by reducing readmissions and other medical expenses. In some instances, directors reported using outcome data from their own programs to justify the program’s continuation.

Several programs benefited from sharing space and administrative resources with physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation or pulmonary function test labs. In several instances, PR programs benefitted from the financial support of charitable donors.

PR programs that were affiliated with hospitals with lung transplant programs did not report acute financial pressures. The presence of a lung transplant program ensured that programs had a steady source of patients and administrative support because lung transplant patients are required to complete PR before and after transplant.

Proximity of PR gym to pulmonary providers and patients (available resources)

When the PR gym was in the hospital, program directors reported that they engaged patients who were considering PR in facility tours or offered tours to inpatient providers. When PR gyms were in the same building as pulmonary clinics, it allowed outpatients to meet patients engaging in PR and increased interaction between PR clinicians and referring providers.

Support from hospital leadership (leadership engagement)

On every visit, there was a statement that leadership support was strong for PR. In some instances, support from hospital administrators was attributed to an individual leader’s dedication to PR; in one case, a leader had worked as a respiratory therapist in PR. In many instances, support for PR was attributed to its effect on COPD hospital readmissions.

Dedication to quality improvement and or research (learning climate)

We consistently heard a commitment to quality improvement and, in a few cases, academic research. The degree of sophistication varied, but in many hospitals, clinicians reported using data to inform decisions about PR.

Process

Outreach and navigation during hospitalization (formally appointed internal implementation leaders)

In three hospitals, we interviewed nurses and respiratory therapists who were responsible for connecting with patients in the hospital. Their titles were navigator or inpatient educator. They provided education and discharge planning to patients with COPD. They were available to triage calls from patients after discharge. At one large hospital, the COPD educator reviewed a daily list of patients admitted for COPD, met with patients multiple times during their stay, and enrolled patients in a text-based program to monitor their health status. Although the educator was not tasked with improving enrollment in PR, she noted that connecting a patient with a pulmonologist would often lead to PR. This is an example of a program that holistically improved the quality of care for patients with COPD with the unintended benefit of increasing PR enrollment.

Champions and external change agents

Several programs had PR champions who were dedicated to raising awareness of PR at the hospital and tenacious in their efforts to enroll patients. In one instance, there was a foundation that invested in the establishment of a network of PR programs and facilitated regional collaboration, and acted as a strong external agent.

Characteristics of Individuals

Education of clinicians to increase referrals (knowledge and beliefs about the intervention)

Education of referral sources, primarily pulmonologist and primary care physicians, was a focus of PR programs. Most programs reported that outpatient pulmonologists were the most significant source of referrals.

Viewpoints varied on when and who should refer patients hospitalized for an exacerbation of COPD. Many providers argued that referral to PR should happen while the patient is hospitalized or being discharged, and the entire team should be empowered to refer patients to PR. Some hospitals that took this approach used information technology to facilitate referrals before discharge.

In other hospitals, it was the role of the outpatient pulmonologist to determine whether PR was appropriate. Although inpatient clinicians might bring up PR, the ultimate responsibility for referring to PR was with the outpatient provider. In these hospital systems, there was an emphasis on ensuring the patient had a follow-up appointment before leaving the hospital.

Less common approaches included making providers aware of who was referring the most patients to PR (i.e., audit and feedback). In one hospital, variable compensation was tied to referral rates.

Patient education (knowledge and beliefs about the intervention)

Many programs distributed brochures to patients. Some reported conducting outreach in the community, for example, sharing stories about PR in the local media. Furthermore, COPD navigators reported discussing PR with patients when appropriate.

Intervention Characteristics

Direct assistance in overcoming patient barriers to attending PR (adaptability and cost)

Transportation was an often-cited barrier, and some hospitals addressed this by providing transportation and parking validation. One hospital system provided patients with rideshare rides to PR. Hospitals addressed the cost of PR to the patient through financial counseling services or, in rare instances, offered small scholarships. Hospitals addressed the barrier of the timing of sessions either by reducing the number of weekly sessions a patient had to attend or increasing the hours offered.

Discussion

Improving participation in PR, particularly after a hospitalization for an exacerbation of COPD, is a national priority (24). This is the first study to use a positive-deviance approach to characterize the strategies of hospitals that achieve relatively high rates of PR attendance within 90 days of discharge for patients hospitalized with COPD. We found that high-performing hospitals were broadly focused on improving care for patients with COPD, some in response to CMS’ HRRP. These hospitals had systems in place to identify patients hospitalized with COPD, which enabled patient education and discharge planning. In addition, high-performing hospitals had effective interprofessional and patient communication, programs had champions or external change agents, and support from hospital leadership. Direct strategies included education of referral sources, education of patients, and direct assistance in overcoming barriers, such as transportation.

Research on the barriers and facilitators to enrollment in PR has highlighted the complexity of the challenge of increasing rates of PR after hospitalization for COPD at all degrees: from inadequate Medicare reimbursement to providers’ lack of awareness of PR or its benefits (17). At the patient level, barriers include transportation, cost, lack of motivation, low self-efficacy, fear of exercise, and breathlessness (25). Furthermore, women, underrepresented minorities, patients of lower socioeconomic status, and those living further away from PR programs are less likely to attend.

Interventions to increase referrals and enrollment have produced mixed results (26). There is evidence that efforts to provide structured, evidence-based COPD education to patients or providers improve referrals and subsequent uptake of PR (27, 28). For example, in one randomized controlled trial, patients who received home visits from COPD nurses had higher PR attendance rates and knowledge of COPD than the control group (29). Similarly, we found COPD navigators may play an important role in improving rates of PR. Results from studies that have tested strategies focused on increasing PR uptake are mixed. For example, showing patients an educational video about PR or group opt-in sessions, which were designed to increase knowledge of PR and leverage group dynamics to increase uptake, found no effect (30, 31). An intervention that tested the effect of giving patients a manual on COPD treatments found no increase in the intervention group but did increase PR enrollment in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged subgroup (28).

Research in cardiac rehabilitation enrollment is more established and may offer strategies that could be applied to PR. A 2019 Cochrane review assessed interventions designed to increase patient enrollment in, adherence to, and completion of cardiac rehabilitation (32). There was evidence that interventions delivered by a nurse or allied healthcare provider or in a face-to-face format were associated with increased enrolment. Interventions to increase adherence were effective, particularly if delivered remotely. These results from cardiac rehabilitation studies suggest the use of COPD navigators and connections in the hospital may increase PR enrollment (33).

In 2014, CMS added COPD to the conditions for which hospitals with high all-cause 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization are financially penalized. Although this decision was controversial, the change seems to have contributed to an increased focus on improving outcomes for patients with COPD (20). It appears hospitals were motivated by the challenge to reduce readmissions and invested in technology and human resources to improve outcomes for patients with COPD. The diversity of these efforts may be driven by the lack of evidence for interventions that reduce rehospitalizations after COPD exacerbations. Although enrollment in PR rarely occurs within 30 days of discharge, the focus on identifying hospitalized patients, conducting bedside patient education, disease self-management, and discharge planning was all part of strategies that may have contributed to the relatively high rates of PR at the hospitals we visited.

Strengths and Limitations

We believe that this is the first positive-deviance study to quantify hospital-specific rates of PR and to conduct site visits at high performers. Furthermore, we enrolled a diverse group of hospitals and interviewed a multidisciplinary set of practitioners. In addition, our study was informed by the literature on the barriers and facilitators to PR, and the CFIR informed our interview guide and interpretation of the data gathered through site visits.

A limitation of our study was that there was less natural variation in rates of participation in PR than we anticipated, making it difficult to distinguish high performers. As such, even the sites we identified as high performers did not achieve high absolute rates of participation. In addition, the qualitative nature of the study meant that we could not test the hypotheses generated from these site visits. It is possible that hospitals with lower degrees of performance would report similar contextual factors and strategies to those that we studied. In addition, we visited several PR programs with affiliated lung transplant programs, and this may contribute to their relatively high rates, but it is not a reproducible strategy. Finally, because our recruitment efforts were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of site visits was lower than planned, and hospitals in the western region of the United States were excluded from our sample.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that successful efforts to increase rates of PR will be most effective when they are part of broader strategies to improve outcomes for patients with COPD by prioritizing the identification of patients hospitalized with COPD and providing targeted outreach to ensure appropriate discharge planning and connection to resources, including PR. Further research is necessary to test the generalizability of our findings.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K23HL135440-01A1 [Q.R.P.] and R01HL133046). The funders had no role in data collection, management, or analysis; study design, conduct, or interpretation of study findings; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Author Contributions: P.K.L., T.L., M.S.S., V.M.P.-P., Q.R.P., K.M., and P.S.P. conceived of and designed the study. P.S.P. and A.P. analyzed quantitative data. K.A.S., K.M., and K.B. analyzed the qualitative data. P.K.L., M.S.S., V.M.P.-P., R.L.Z., K.A.S., and B.H. conducted site visits and scheduling. K.A.S. led all interviews. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. K.A.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors give final approval of the version to be published. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Arias E, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db427.pdf

- 2. Wheaton AG, Ford ES, Thompson WW, Greenlund KJ, Presley-Cantrell LR, Croft JB. Pulmonary function, chronic respiratory symptoms, and health-related quality of life among adults in the United States—national health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2010. BMC Public Health . 2013;13:854. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2020. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf

- 5. Puhan MA, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Steurer J. Respiratory rehabilitation after acute exacerbation of COPD may reduce risk for readmission and mortality—a systematic review. Respir Res . 2005;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ryrsø CK, Godtfredsen NS, Kofod LM, Lavesen M, Mogensen L, Tobberup R, et al. Lower mortality after early supervised pulmonary rehabilitation following COPD-exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med . 2018;18:154. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0718-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates CJ, Troosters T. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2016;12:CD005305. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greening NJ, Williams JEA, Hussain SF, Harvey-Dunstan TC, Bankart MJ, Chaplin EJ, et al. An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ . 2014;349:g4315. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Revitt O, Sewell L, Morgan MDL, Steiner M, Singh S. Short outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme reduces readmission following a hospitalization for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology . 2013;18:1063–1068. doi: 10.1111/resp.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindenauer PK, Stefan MS, Pekow PS, Mazor KM, Priya A, Spitzer KA, et al. Association between initiation of pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for COPD and 1-year survival among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA . 2020;323:1813–1823. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maddocks M, Kon SSC, Singh SJ, Man WDC. Rehabilitation following hospitalization in patients with COPD: can it reduce readmissions? Respirology . 2015;20:395–404. doi: 10.1111/resp.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nici L, Raskin J, Rochester CL, Bourbeau JC, Carlin BW, Casaburi R, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: what we know and what we need to know. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev . 2009;29:141–151. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181a85cda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wedzicha JA, Miravitlles M, Hurst JR, Calverley PM, Albert RK, Anzueto A, et al. Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J . 2017;49:1600791. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00791-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spitzer KA, Stefan MS, Priya A, Pack QR, Pekow PS, Lagu T, et al. Participation in pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among Medicare beneficiaries. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2019;16:99–106. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201805-332OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oates GR, Niranjan SJ, Ott C, Scarinci IC, Schumann C, Parekh T, et al. Adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a qualitative exploration of patient perspectives on barriers and facilitators. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev . 2019;39:344–349. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robinson H, Williams V, Curtis F, Bridle C, Jones AW. Facilitators and barriers to physical activity following pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a systematic review of qualitative studies. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med . 2018;28:19. doi: 10.1038/s41533-018-0085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cox NS, Oliveira CC, Lahham A, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation referral and participation are commonly influenced by environment, knowledge, and beliefs about consequences: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. J Physiother . 2017;63:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thorpe O, Johnston K, Kumar S. Barriers and enablers to physical activity participation in patients with COPD: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev . 2012;32:359–369. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e318262d7df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janaudis-Ferreira T, Tansey CM, Harrison SL, Beaurepaire CE, Goodridge D, Bourbeau J, et al. A qualitative study to inform a more acceptable pulmonary rehabilitation program after acute exacerbation of COPD. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2019;16:1158–1164. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-854OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prieto-Centurion V, Markos MA, Ramey NI, Gussin HA, Nyenhuis SM, Joo MJ, et al. Interventions to reduce rehospitalizations after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2014;11:417–424. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201308-254OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci . 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci . 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res . 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2017. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/all-publications-and-resources/copd-national-action-plan

- 25. Spitzer KA, Stefan MS, Drake AA, Pack QR, Lagu T, Mazor KM, et al. “You leave there feeling part of something”: a qualitative study of hospitalized COPD patients’ perceptions of pulmonary rehabilitation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2020;15:575–583. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S234833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Early F, Wellwood I, Kuhn I, Deaton C, Fuld J. Interventions to increase referral and uptake to pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD: a systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2018;13:3571–3586. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S172239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lange P, Rasmussen FV, Borgeskov H, Dollerup J, Jensen MS, Roslind K, et al. KVASIMODO Study Group The quality of COPD care in general practice in Denmark: the KVASIMODO study. Prim Care Respir J . 2007;16:174–181. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harris M, Smith BJ, Veale AJ, Esterman A, Frith PA, Selim P. Providing reviews of evidence to COPD patients: controlled prospective 12-month trial. Chron Respir Dis . 2009;6:165–173. doi: 10.1177/1479972309106577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zwar NA, Hermiz O, Comino E, Middleton S, Vagholkar S, Xuan W, et al. Care of patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust . 2012;197:394–398. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Graves J, Sandrey V, Graves T, Smith DL. Effectiveness of a group opt-in session on uptake and graduation rates for pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis . 2010;7:159–164. doi: 10.1177/1479972310379537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barker RE, Jones SE, Banya W, Fleming S, Kon SSC, Clarke SF, et al. The effects of a video intervention on posthospitalization pulmonary rehabilitation uptake. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;201:1517–1524. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201909-1878OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Chaves GS, Davies P, Taylor RS, Grace SL. Interventions to promote patient utilisation of cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2019;2:CD007131. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007131.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benz Scott L, Gravely S, Sexton TR, Brzostek S, Brown DL. Effect of patient navigation on enrollment in cardiac rehabilitation. JAMA Intern Med . 2013;173:244–246. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]