Abstract

Objective

To evaluate how pediatric indications for tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy relate to gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

Methods

Included consecutive pediatric patients who underwent tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy from a single tertiary academic institution between 2012 and 2019. Logistic regression analysis was used to measure association between the indication for tonsillectomy and the demographic variables gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

Results

Of the 1106 children included in this study, 53% were male and 47% were female. Half of the children were White, 40% were African American, 6% were Hispanic and 4% were other. The most common indication for surgery was upper airway obstruction alone (66%), followed by obstruction and infection (22%), and recurrent infections (12%). We found that male gender (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.24–2.04), African American race (OR 2.76, 95% CI 2.08–3.65), and younger age were associated with greater odds of presenting with upper airway obstruction as the indication for tonsillectomy. Conversely, male gender (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44–0.92), African American race (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.26–0.61), and younger age were associated with lower odds of presenting with recurrent infection as the indication for tonsillectomy.

Conclusions

Male gender, African American race, and young age are risk factors for tonsillar surgery due to airway obstruction. Female gender, White race, and older age are risk factors for tonsillar surgery due to recurrent throat infections.

Level of Evidence

3

Keywords: adenotonsillectomy, age, ethnicity, gender, obstructive sleep apnea, pediatric, racial disparities, sleep disordered breathing, tonsillectomy, tonsillitis

1. INTRODUCTION

In explaining racial and ethnic differences in disease, the medical anthropologist and sociologist, Anthony Polednak, states that it is easier to describe these differences than to explain them. Polednak further asserts that any comparison must include age and sex. 1 As such, the chief focus of this research is on the impact of race/ethnicity, gender, and age in pediatric tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy patients.

Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures, with more than 500,000 cases performed in the United States annually. 2 Historically, tonsillectomies were performed due to the theory of “focal infection”, wherein the tonsils were to be a portal of entry for these infections. In the last few decades there has been an increased understanding of the negative effects of upper airway obstruction, which has emerged as the most common indication for tonsillar surgery in children. 3 , 4 , 5

Racial and ethnic differences exist in disease. Well‐documented examples of racial disparities in the adult population include disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity. However, the underlying reasons for these disparities are less well understood. 6 , 7 In the pediatric population, authors have described variance in the epidemiology presentation and surgical complication rates of adenotonsillar disease. However, there is disagreement as to whether these differences are genetic, ethnic, life style, socioeconomic or some other yet to be determined factor. 8 , 9 To this end this paper attempts to add to the dialogue by exploring the disparities in tonsillectomy rates with or without adenoidectomy in a diverse cohort of children in a university‐based otolaryngology clinic.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was performed by a single surgeon (EHH) at a tertiary care center. The de‐identified data was exempt from approval by the University Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Inclusion criteria

All children 0 to 18 years of age presenting to the senior author for tonsillar or adenotonsillar surgery were included in this study. These data were collected prospectively and analyzed retrospectively.

2.2. Exclusion criteria

Children with Down syndrome, suspected tumor, post‐transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), Quinsy tonsillectomy, periodic fever aphthous stomatitis pharyngitis, and adenopathy (PFAPA), pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcus (PANDAS) syndrome, craniofacial syndromes including cleft lip and/or cleft palate, immunosuppression, storage disease or undergoing adenoidectomy without tonsillectomy were excluded from this analysis.

2.3. Age

Age was listed in years rather than months and stratified into four groups for the purpose of this analysis. These include an infant‐toddler group (ages 0 to <2 years); a pre‐school group (ages 2 to <5 years); a primary school group (ages 5 to <12 years); and a pre‐teen/teenage group (ages 12 to <18 years).

2.4. Race/ethnicity

The Race/ethnicity of the children was divided into four categories: White, African American, non‐black Hispanic, and other. Native Americans, children of mixed race, Persians and Asians were classified as other due to the small number of patients in these groups.

2.5. Indications for surgery

The indications for surgery were stratified as follows: (a) upper airway obstruction only (b) recurrent throat infections only (c) mixed obstruction and recurrent infections

2.6. Upper airway obstruction

Upper airway obstruction was deemed to be present if the child exhibited snoring, mouth breathing or episodes of witnessed apnea in association with the physical exam findings of enlarged tonsils of sizes 3 or 4 on the Brodsky scale. A diagnostic polysomnogram was not always performed in non‐syndromic or non‐obese children over the age of 3 years when the clinical history and physical findings supported the diagnosis. Lateral neck radiographs were occasionally obtained to assess the adenoids. Adenoids were considered to be small, medium or large based on the adenoid‐to‐nasopharynx (AN) ratio. An AN ratio of <0.33 indicated small adenoids, an AN ratio of 0.33 to 0.66 indicated moderate adenoids enlargement and a ratio of >0.66 characterized large adenoids. The adenoids were occasionally evaluated by flexible nasopharyngeal endoscopy when it was felt that such an assessment would offer help in the decision‐making process in determining who was a candidate for surgery.

2.7. Recurrent throat infection

Children with repeated throat infections were candidates for tonsillectomy. Group A beta hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) was often the offending organism, but children with frequent bouts of non‐GABHS tonsillopharyngitis which were accompanied by fever and cervical adenitis were considered reasonable candidates for surgery. While the Paradise criteria formed the basis for recommending surgery for many of the children, other factors were considered in determining who was a candidate, such as a history of multiple antibiotic allergies, a history of excessive school absences, or failure to eradicate the GABHS carrier state. 10

2.8. Obstruction and recurrent throat infection

Children were placed in this category if their primary clinical history was that of obstruction but who also had recurrent throat infections. Similarly, children whose primary presentation was that of recurrent throat infection but who had significant snoring and mouth breathing were also included in this category. For the purpose of this research there was no distinction made to determine which diagnosis (obstruction or infection) was dominant.

2.9. Other procedures

Other otolaryngologic surgeries were often conducted in the same setting but were not subjected to analysis for the purpose of this study. Other procedures performed included inferior turbinate reduction, myringotomy with or without tubes, maxillary sinus puncture, cilia biopsy and direct laryngoscopy.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including proportions and means were used to report demographic and clinical features of the population.

- Independent variables

- Age had four factors: 0–2 years, 2–5 years, 5–12 years, and 12–18 years;

- Race had four factors: White, African American, Hispanic, and Other;

- Gender had two factors: Male and Female.

- Dependent variables

- Indications for surgery: airway obstruction, recurrent infections, mixed obstruction and infection

For all analyses, statistical significance was determined to be p ≤ .05. Chi‐square test for independence was conducted to determine the relationship between the indication for tonsillectomy (airway obstruction, recurrent infections, mixed obstruction, and infection) and each independent variable (gender, race/ethnicity, and age). Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to compare patients with upper airway obstruction or infection based upon their gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

3. RESULTS

A total of 1106 consecutive pediatric patients underwent tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy from 2012 to 2019. Age range: 1–18 years with a mean age of 6.06 years. The cohort was evenly divided by gender (53% male vs. 47% female). The vast majority of patients were White (50%) or Black (40%), with a small proportion of patients identifying as Hispanic (6%) or other (4%). The most common indication for tonsillectomy was upper airway obstruction (66%), with a smaller proportion of patients presenting with recurrent infections (12%) or both airway obstruction and recurrent infections (22%; Table 1). By stratifying the cohort by indication for surgery, we found that patients presenting with airway obstruction are more frequently male, African American, and of younger age, while patient presenting with infection are more frequently female, White, and of older age (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of patients undergoing tonsillectomy

| Variables | Overall |

|---|---|

| n = 1106 | |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 587 (53.1) |

| Female | 519 (46.9) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 551 (49.8) |

| African American | 449 (40.6) |

| Hispanic | 66 (6.0) |

| Other | 40 (3.6) |

| Age, y, n (%) | |

| 0 to >2 | 111 (10) |

| 2 to >5 | 485 (43.9) |

| 5 to >12 | 439 (39.7) |

| 12 to >18 | 71 (6.4) |

| Indication for surgery, n (%) | |

| Airway obstruction | 736 (66.5) |

| Recurrent infections | 130 (11.8) |

| Infection and obstruction | 240 (21.7) |

Abbreviations: n, sample size; y, years.

TABLE 2.

Demographics of patients undergoing tonsillectomy stratified by surgical indication

| Variables | Obstruction | Infection | Infection and obstruction | p value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 736 | n = 130 | n = 240 | ||

| Gender, n (%) | .001 | |||

| Male | 419 (56.9) | 56 (43.1) | 112 (46.7) | |

| Female | 317 (43.1) | 74 (56.9) | 128 (53.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| White | 313 (42.5) | 89 (68.5) | 149 (62.1) | |

| African American | 352 (47.8) | 32 (24.6) | 65 (27.1) | |

| Hispanic | 43 (5.9) | 3 (2.3) | 20 (8.3) | |

| Other | 28 (3.8) | 6 (4.6) | 6 (2.5) | |

| Age, y, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| 0 to >2 | 96 (13) | 5 (3.8) | 10 (4.2) | |

| 2 to >5 | 387 (52.6) | 20 (15.4) | 78 (32.5) | |

| 5 to >12 | 233 (31.7) | 75 (57.7) | 131 (54.6) | |

| 12 to >18 | 20 (2.7) | 30 (23.1) | 21 (8.7) |

Abbreviations: n, sample size; y, years.

Values with p value <.05 labeled in bold.

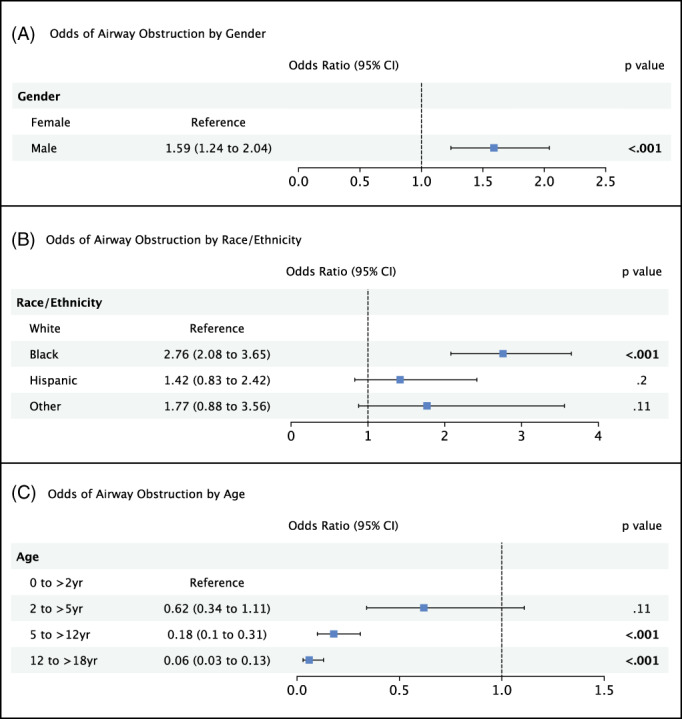

3.1. Gender

According to the logistic regression analysis, odds of presenting with airway obstruction were 59% higher among male patients compared with female patients (Odds Ratio [OR] 1.59, 95% Confidence Interval [95% CI] 1.24–2.04, p < .001; Figure 1). Odds of presenting with infection were 37% lower among male patients compared with female patients (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44–0.92, p < .001; Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Logistic regression model comparing odds of presenting with upper airway obstruction as the indication for tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy by (A) gender, (B) race/ethnicity, and (C) age.

FIGURE 2.

Logistic regression model comparing odds of presenting with recurrent throat infection as the indication for tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy by (A) gender, (B) race/ethnicity, and (C) age.

3.2. Race/ethnicity

The odds of presenting with airway obstruction were 176% higher among African American patients compared with White patients (OR 2.76, 95% CI 2.08–3.65, p < .001; Figure 1). There was not a significant difference in odds of presenting with airway obstruction for patients classified as Hispanic or Other. Compared with White patients, odds of presenting with recurrent infections were 60% lower for African American patients (OR 0.4 95% CI 0.26–0.61, p < .001) and 75% lower for Hispanic patients (OR 0.25 95 CI 0.08–0.8, p = .02; Figure 2). There was no significant difference in odds of presenting with infection for patients classified as other.

3.3. Age

Among children undergoing tonsillectomy, odds of presenting with airway obstruction tended to decrease with age. Compared with the 0–2 year‐old group, odds of presenting with airway obstruction were 82% lower in the 5–12 year‐old group (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.1–0.31, p < .001) and 94% lower in the 12–18 year‐old group (OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.03–0.13, p < .001; Figure 1). Conversely, odds of presenting with infection tended to increase with age. Compared with the 0–2 year‐old group, odds of presenting with infection were 4.37 times as high in the 5–12 year‐old group (OR 0.37, 95% CI 1.72–11.08, p = .002) and 15.5 times as high in the 12–18 year‐old groups (OR 15.51, 95% CI 5.63–42.72, p < .001; Figure 2).

4. DISCUSSION

Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy remains the most common major surgery in childhood. Historically, the indication for tonsillar surgery in children was recurrent throat infection with GABHS bacteria. 3 , 4 , 5 However, recently clinicians have been more concerned with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) or sleep‐disordered breathing (SDB) and the adverse impact of these disorders on children. Phenomena such as behavioral disorders, poor school performance, failure to thrive and secondary enuresis have all contributed to the increased interest in upper airway obstruction in children. As such, obstruction has emerged as the most common indication for tonsillar surgery in children. 3 , 4 , 5 Certainly this is the case in the current study where only 12% of children had surgery for throat infections but 66% of the children had surgery for obstruction and 22% of the children underwent surgery for a combination of obstruction and infection.

4.1. Racial/ethnic differences

Race/ethnicity has not been a common focus within pediatric OSA or SDB literature. Lumeng and Chervin, in a literature review of 48 studies, found that only six papers looked at the association between race/ethnicity and the prevalence of SDB and snoring. However, of the six studies, four found that race was a significant independent risk factor. 11 In our study, which examines the common pediatric indications for adenotonsillar surgery, it is no surprise that statistically significant patterns also emerge based on race/ethnicity.

Our data indicate that odds of presenting with upper airway obstruction as the indication for tonsillectomy for African American patients are 2.76 times the odds for White patients (Figure 1). This is consistent with the findings in several other studies evaluating the relative prevalence of pediatric OSA across different racial/ethnic groups. Redline et al. determined that African American children are 3.5 times as likely to have SDB compared with White children. They also identified that the increased risk for airway obstruction in African American children is independent of obesity or other respiratory problems. 12 Goldstein et al. determined that there was an increased prevalence of snoring in African American and Hispanic children when compared with Whites. On multivariate analysis, African American race/ethnicity and prematurity were independently associated with snoring. 13 Interestingly, Goldstein did not find a relationship between body mass index (BMI) and sleep disordered breathing. Villanueva et al. also noted an increase in the prevalence and severity of OSA in African American children. 14 Boss and her co‐authors reviewed the published literature regarding the pediatric aspects of this disorder. In a systematic review of 24 articles on SDB in children, they were able to highlight that racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic minorities are at greater risk for SDB. 8 Even in examining respiratory complications after adenotonsillectomy, Horwood et al. asserted that ethnicity may be considered an independent risk factor in such surgery. 9 The increased prevalence of OSA and SDB among the African American pediatric population appears to be driving our finding that African American children are more likely to receive tonsillectomy due to airway obstruction. While it is difficult to assess in the current study, these results may also indicate that the overall African American pediatric population is at greater risk of requiring tonsillectomy.

Could there be other reasons such as genetics and/or immunologic changes for this now well documented disparity? The subject of a genetic basis for OSA in certain populations has been studied by several researchers. 15 , 16 A candidate gene study suggested that genes operate through intermediate pathways to influence sleep apnea. 16 Similarly, genetic differences in tonsillar interleukin 4 expression may result in a lack of lymphoid apoptosis with subsequent cellular proliferation. 17 Further research is needed, but it is plausible that genetics contribute to the observed differences in OSA seen in African American and Hispanic children.

Are there anatomic differences? One study determined that Asians tend to have more severe OSA for an even lesser degree of obesity than Whites. The authors have attributed this finding to the tendency towards short skull bases occurring in this population. 18 In looking at African Americans, researchers have pointed to the presence of lower lung volumes as contributing to upper airway obstruction. Patel et al. determined that the cross‐sectional airway is smaller in African American children. Moreover, they found that this trait is heritable and is a possible contributor to OSA, again pointing to a possible genetic linkage. 19 Further, in a study by Squier et al. it was noted that there is a decrease in end expiratory lung volume (EELV) in African Americans affecting the critical closing pressure of the pharyngeal airway, which may contribute to sleep apnea. 20 Lastly, Côté et al., found that African American children under 2 had a 12.5 times higher obstructive apnea hypopnea index (OAHI) than that of a matched Caucasian population. They hypothesized that a shorter cranial base and difference in fat distribution could play a role. 21

Social, cultural and personal factors might also affect the diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of children from different ethnic groups. For example, a paper published by Boss et al., discusses decreased utilization of medical care, especially specialist visits, in ethnic minorities including African Americans and Hispanics. 8 Additionally, Bhattacharyya et al., found that Black and Hispanic children had both an increased risk for a revisit and increased odds of acute pain after tonsillectomy compared with white children. 22

4.2. Age

Age is also significantly associated with indication for tonsillar surgery in children. Don et al., found that children <3 years of age had more severe OSA. 23 In looking at our study, where the patients were stratified into four age groups, there was clear statistical evidence to support an age‐based effect. We found that compared with children <2 years of age, children 5 to 12 years of age were 82% less likely to have surgery for OSA and children 12–18 years of age were 94% less likely to have surgery for OSA. The reason for higher rates of upper airway obstruction in younger children may relate to a smaller airway and the size of the tonsils and adenoids relative to the cross sectional area of the pharynx. 24

4.3. Gender

In a study examining OSA in 215 children <2 years old, Côté et al. found that male children made up 64% of the population versus only 36% being female. This is in line with our findings showing that males are at higher risk for tonsillectomy/adenotonsillectomy due to upper airway obstruction. The reason for this gender discrepancy, especially for airway obstruction, is not well understood. Previously, it was hypothesized that the disparity in prevalence of airway obstruction between males and females occurred after puberty with hormonal changes. 11 , 21 However, other studies have demonstrated that there is a higher prevalence of airway obstruction in male infants compared with female infants, suggesting that there are other variations in metabolic rates, physical maturation, or mechanics of breathing that may contribute to this difference. 25

4.4. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Our cohort is limited to surgical patients. Therefore, we are unable to make conclusions regarding the population at large. Due to socio‐economic disparities in health care and provider referral patterns, it is unknown whether this non‐random sample of patients is generalizable to the pediatric population outside of Washington DC. With that being said, our patient population resembles that of the Washington DC Census data from 2020 which showed 41% African American, 38% White, 11% Hispanic and 10% other compared with 40.6% African American, 49.8% white, 6.0% Hispanic, and 3.6% other in our study. 26 In this study, we were unable to control for co‐morbidities such as pre‐maturity, asthma, and allergies, or environmental factors such as breastfeeding, exposure to secondary tobacco smoke, and BMI, which have been associated with OSA and SBD.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, looking at the common pediatric indications for adenotonsillar surgery, there were statistically significant differences based on race/ethnicity, age, and gender. When OSA was the indication for surgery, patients tended to be male, African American, and of younger age. When recurrent infection was the indication for surgery, patients tended to be female, white, and of older age. The reasons for these disparities are not clear. It may be genetic, immunologic, socioeconomic or environmental, but more than likely it is multifactorial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Dr. Millicent Collins for her review and editing of the manuscript.

Han CJ, Bergman M, Harley RJ, Harley EH. The pediatric indications for tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy: Race/ethnicity, age, and gender. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2023;8(2):577‐583. doi: 10.1002/lio2.1017

REFERENCES

- 1. Polednak AP. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Disease. Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bohr C, Shermetaro C. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darrow DH, Siemens C. Indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:6‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grob GN. The rise and decline of tonsillectomy in twentieth‐century America. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62:383‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramos SD, Mukerji S, Pine HS. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60:793‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585‐1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang H, Rodriguez‐Monguio R. Racial disparities in the risk of developing obesity‐related diseases: a cross‐sectional study. Ethn Dis. 2012;22:308‐316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boss EF, Smith DF, Ishman SL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep‐disordered breathing in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:299‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horwood L, Nguyen LH, Brown K, Paci P, Constantin E. African American ethnicity as a risk factor for respiratory complications following adenotonsillectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:147‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. Efficacy of tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection in severely affected children. Results of parallel randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:674‐683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:242‐252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Redline S, Tishler PV, Schluchter M, Aylor J, Clark K, Graham G. Risk factors for sleep‐disordered breathing in children. Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1527‐1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldstein NA, Abramowitz T, Weedon J, Koliskor B, Turner S, Taioli E. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of snoring and sleep disordered breathing in young children. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:163‐171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villaneuva AT, Buchanan PR, Yee BJ, Grunstein RR. Ethnicity and obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:419‐436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaultier C, Guilleminault C. Genetics, control of breathing, and sleep‐disordered breathing: a review. Sleep Med. 2001;2:281‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larkin EK, Patel SR, Goodloe RJ, et al. A candidate gene study of obstructive sleep apnea in European Americans and African Americans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:947‐953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. López‐González MA, Díaz P, Delgado F, Lucas M. Lack of lymphoid cell apoptosis in the pathogenesis of tonsillar hypertrophy as compared to recurrent tonsillitis. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:469‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang SJ, Chae KY. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and sequelae. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:863‐871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel SR, Frame JM, Larkin EK, Redline S. Heritability of upper airway dimensions derived using acoustic pharyngometry. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1304‐1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Squier SB, Patil SP, Schneider H, Kirkness JP, Smith PL, Schwartz AR. Effect of end‐expiratory lung volume on upper airway collapsibility in sleeping men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2010(109):977‐985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Côté V, Ruiz AG, Perkins J, Sillau S, Friedman NR. Characteristics of children under 2 years of age undergoing tonsillectomy for upper airway obstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:903‐908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bhattacharyya N, Shapiro NL. Associations between socioeconomic status and race with complications after tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151:1055‐1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Don DM, Geller KA, Koempel JA, Ward SD. Age specific differences in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1025‐1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adedeji TO, Amusa YB, Aremu AA. Correlation between adenoidal nasopharyngeal ratio and symptoms of enlarged adenoids in children with adenoidal hypertrophy. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2016;13:14‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kato I, Franco P, Groswasser J, Kelmanson I, Togari H, Kahn A. Frequency of obstructive and mixed sleep apneas in 1,023 infants. Sleep. 2000;23:487‐492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bureau USC. District of Columbia: Hispanic or Latino, and not Hispanic or Latino by race. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=race%2Fethnicity%20DC&g=0400000US11&tid=DECENNIALPL2020.P2.