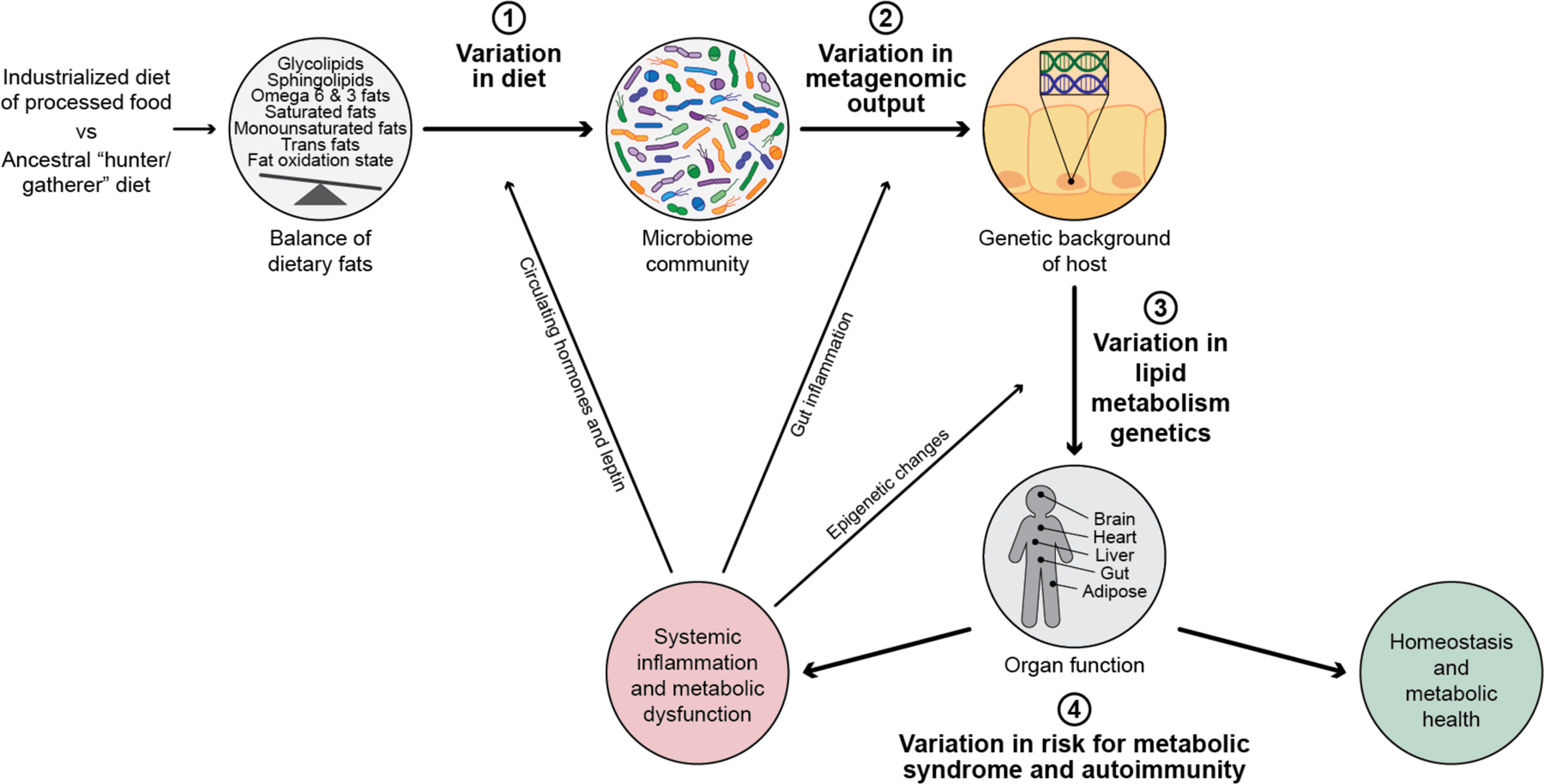

Figure 3: The function of gut microbiome enzymes responding to dietary lipids are a key step to explain the variation in risk for metabolic syndrome and autoimmunity across human populations.

Metabolic syndrome and autoimmunity are diseases of more recent occurrence, and are seen at much higher levels in human populations eating an industrialized and processed food rich diet. This is compared to an ancestral diet which was common among hunter gatherer populations most of human history. Ingestion of dietary lipids are essential for human health and have a large role in all aspects of mammalian biology, and this lipid profiling we ingest has rapidly been changing through industrialization. As the incidence of these disease rise dramatically, it is clear there is variation from human to human on their risk profile for developing systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. This variation in susceptibility for disease is multifactorial and can be explained by 3 main variables as summarized here in this figure; 1) Variation in diet consumed, 2) Variation in metagenomic output by the microbiome and 3) variation in activity and function of metabolism genes from each individual’s genome. Ultimately the outcome of these 3 variables results in; 4) the variation of risk for metabolic syndrome and autoimmunity. The percentage of each of these variables contributing risk is unknown. Human genetic risk explains some variance, however there is a large environmental component to risk of these conditions. The connection between dietary lipid input, and metagenomic output of the microbiome interacting with genetics are crucial, understudied variances in risk for onset of metabolic syndrome and autoimmunity. Systematic inflammation, once initiated, can influence every variable in the process, including what humans crave (e.g. leptin signaling), inflammation-induced ecological shift in microbiome function and epigenetic changes in host gene expression (e.g. stress related), as visually shown here by the arrows.