Abstract

Background:

The care partners of hospitalised older adults often feel dissatisfied with the education and skills training provided to them, resulting in unpreparedness and poor health outcomes.

Objective:

This review aimed to characterise and identify gaps in the education and skills training used with the care partners of older adults in the hospital.

Methods:

We conducted a scoping review on the education and skills training practices used with the care partners of hospitalised older adults in the USA via sources identified in the PubMed, PsychINFO and CINAHL databases.

Results:

Twelve studies were included in this review. Results illustrate that nurses utilise multiple modes of delivery and frequently provide education and skills training tailored to the needs of care partners at the latter end of hospital care. The provision of education and skills training varies greatly, however, including who provides education, in what way information is conveyed, and how care partner outcomes are measured.

Conclusion:

This is the first scoping review to describe and synthesise the education and skills training practices used with care partners of hospitalised older adults. Findings highlight the need for education and skills training to be interprofessional, tailored to individual care partners’ needs and begin at, or even before, the hospital admission of older adult patients.

Keywords: Caregiving, education, hospital, older adults, training

Introduction

Each year, individuals aged 65 and older constitute 40% of hospitalisations and account for half of all health care dollars spent in the USA (Gorina et al., 2015). Older adults are also more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of their initial hospitalisation costing an additional $25 million in spending (Hines et al., 2014). To reduce preventable readmissions and costs, the US health care system increasingly relies on unpaid care partners (‘friends or family members’) to meet the growing needs of older adults by providing complex care at home (Bell et al., 2019).

An estimated 34.5 million US residents serve as care partners of older adults with services valued at $470 billion (Reinhard et al., 2019). Care partners perform diverse hands-on tasks, including managing medication, operating medical equipment, coordinating finances and assisting with wound care, dressing, feeding and toileting (Hunt and Reinhard, 2015). To fulfil these responsibilities, the care partners of older adults rely on education and skills training from health care providers regarding medical and nursing care management, assistance with activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living and support services (Hunt and Reinhard, 2015). However, many care partners report limited role-related training, specifically before hospital discharge (Burgdorf et al., 2019).

According to the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, discharge planning is the process of transitioning a patient from one level of care to the next through individualised instruction to patients and their care partners (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2012). The goal of a hospital discharge plan is to improve a patient’s quality of life, ensure continuity of care and increase the preparedness of care partners through education and skill training thereby reducing readmission and future health care spending (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2012).

Practice recommendations and policies are particularly important to realise the hospital discharge plan. The US Agency for Health care Research and Quality offers providers a discharge planning guide called IDEAL (Include, Discuss, Educate, Assess, Listen). This guide recommends interprofessional teams provide education and skills training via verbal, written and teach-back strategies starting from the patient’s admission up until discharge. Topics for education and skills training within IDEAL include medication management, home safety, care regime for the patient’s condition and family support (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.). The Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act is a state-specific statute that further supports hospital discharge planning. This policy requires hospitals to (1) provide patients with the opportunity to identify a care partner; (2) communicate with care partners about discharge plans and (3) provide education to care partners on the patients’ needs (AARP, 2014). Currently, 40 states have passed the CARE Act, but care partner education is only taking place in 32% of hospitals (Rodakowski et al., 2021). The discrepancy between policy enactment and implementation highlights health care systems desire to integrate care partners into care, but barriers in doing so remain pervasive, including visitor restrictions, costs and communication between providers (Leighton et al., 2020). In turn, care partners are often left feeling unprepared and dissatisfied with educational services (Coleman and Roman, 2015).

The purpose of this scoping review is to describe research interventions focussed on care partner education and skills training for hospital discharge preparation, including associated outcomes and suggestions for implementation. Information gleaned from the review can guide research and practice efforts that seek to increase care partners’ preparedness for assuming caregiving responsibilities post-hospital discharge. Researchers can use the results of the review to develop and test care partner education and skills training-focussed intervention studies that aim to fill current gaps in the literature and health care administrators and providers can use the results of this review to develop and implement care partner education and skills training-focussed policies.

Methods

Scoping reviews are appropriate for mapping diverse bodies of the literature, presenting findings of research studies with varied methodologies and providing a descriptive analysis of the research studies (Portney and Watkins, 2009). We conducted this scoping review to identify and chart gaps in current hospital education and skills training practices that involve care partners. A five-step framework guided the review and included: (1) identifying the research question; (2) searching for relevant studies; (3) selecting studies for inclusion; (4) charting extracted data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting results (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005).

Stage I: identifying the research question

The research question used to guide the review was as follows: what, when and how do providers convey and measure educational information and skills training delivered to care partners of hospitalised older adult patients?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

In partnership with a librarian, we developed a broad search strategy using Medical Subject Heading terms pertaining to education, caregiving, hospitalisation and older adults. We searched PubMed, CINAHL Plus and PsychINFO for studies, using the following terms and Boolean procedures related to older adults, care partners and education (Table 1). In total, 1072 studies resulted from the initial database searches.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Search strategies for PubMed, CINAHL and PsychoINFO |

|---|

| 1 ‘aged’ |

| 2 ‘elder’ |

| 3 ‘older adult’ |

| 4 OR 1–4 |

| 5 ‘care partner’ |

| 6 ‘caregiver’ |

| 7 ‘caregiv*’ |

| 8 ‘famil*’ |

| 9 OR 5–8 |

| 10 ‘education’ |

| 11 ‘communication’ |

| 12 ‘instruct*’ |

| 13 ‘training’ |

| 14 ‘discharge’ |

| 15 Limit English |

| 16 Limit United States of America |

Stage 3: study selection

The following criteria were used to screen studies for their relevancy. Inclusion criteria consisted of (a) unpaid care partners; (b) 2/3 of patients had to be aged 65+ or author classified patients as ‘older adult’; (c) hospital setting; (d) content and delivery of educational information and/or skills training in preparation for discharge; (e) care partner outcome measurement and (6) studies published in English between 2000 and 2020. This date range was chosen for inclusivity and relevancy.

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method studies were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria consisted of (a) patients with a mental health diagnosis; (b) systematic reviews and dissertations; (c) studies conducted outside of the USA and (d) no care partner outcome. Patients with a mental health diagnosis or in palliative care were excluded from the review because of their variability in discharge dispositions and planning needs. Studies conducted outside of the USA were also excluded because health care systems and policies regarding education may differ across countries. Studies that did not measure or capture some type of care partner outcome were excluded because the primary focus of this scoping review was to inform practice related to increasing care partners’ preparedness for assuming caregiving responsibilities.

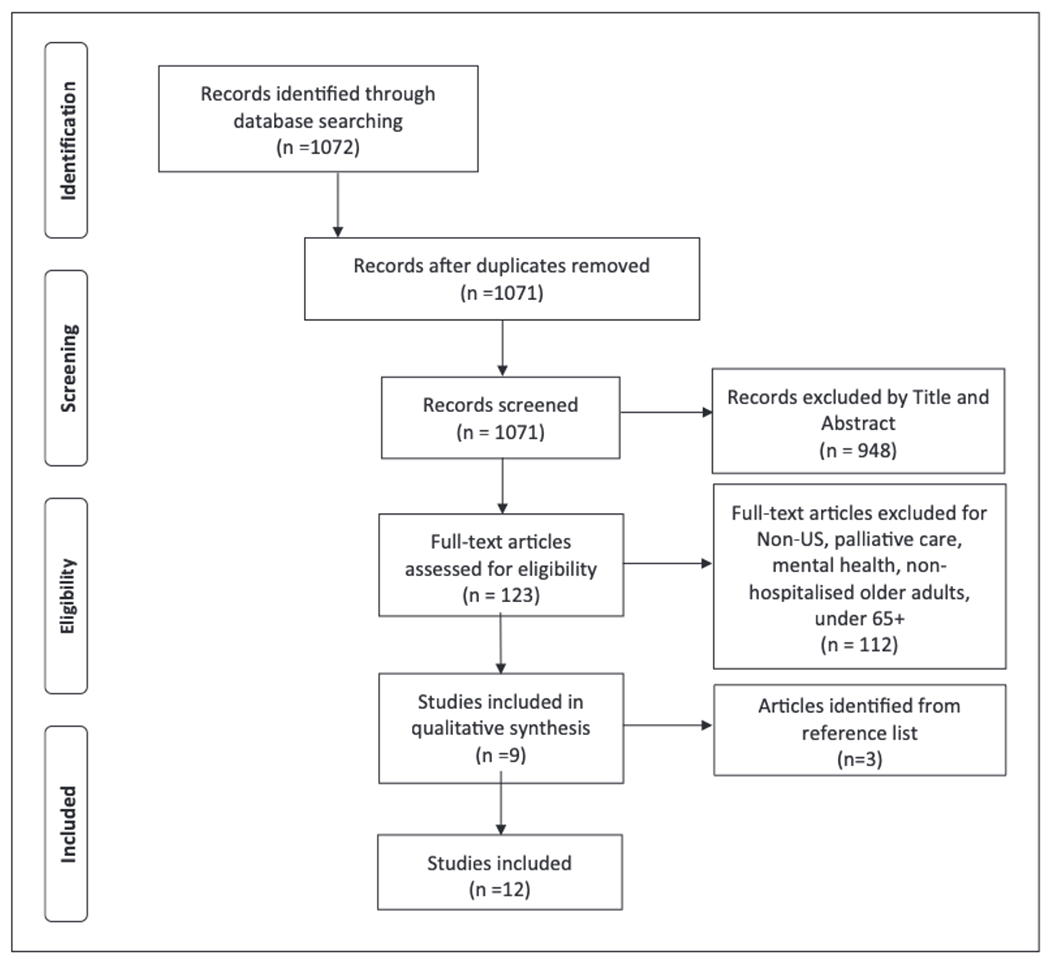

Results from the literature search were imported into a bibliographic software, Zotero, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (S.S. and M.C.) screened 1,072 studies by title and abstract using the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the relevance of studies to the overall aim of this scoping review. After screening, the same reviewers examined the full texts of the remaining 123 studies to further determine if they met the established inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the final included studies were manually searched to ensure all relevant studies were examined. An additional three studies were found from the reference lists. The Equator Network guidelines, specifically the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation guided this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search and study selection process.

Stage 4: charting the data

The reviewers developed an evidence table based on IDEAL which emphasises: (1) the role of providers; (2) the timing of education and skills training; (3) the delivery mode of education and skills training; (4) the content of information conveyed and (5) assessment of care partner outcomes (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.).

The reviewers independently extracted data from the included studies then discussed findings via teleconferencing until a consensus was reached. If disagreement occurred, a third-party researcher (B.F.) was consulted. The following data were extracted: study design, setting/location, patient demographics, care partner demographics, care partner relationship to patient, health care provider, education and skills training content, education and skills training delivery (when, where and how), care partner outcome or assessment measures and results. Consistent with scoping reviews, a quality appraisal of included studies was not conducted (Portney and Watkins, 2009). The level of evidence of included studies was determined using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (Portney and Watkins, 2009).

Results

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

Twelve studies were included after full-text screening. Of those studies, one was level 1B, one was level 2B, six were level 3B, one was level 4 and three were level 5. These studies were published from 2000 to 2017. Table 2 shows key characteristics of included studies such as design, setting, patient demographics, care partner demographics, patient and care partner relationship and care partner outcome measure.

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

| Study characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Author (year) | Study design level of evidence | Setting | Patient demographics | Care partner demographics | Patient and care partner relationship | Care partner outcome measure |

| Bull et al. (2000) | Before and after non-equivalent control group Level 3B | 400–500 bed cardiac units from two Midwest, metropolitan, community hospitals | 1 58 patients with heart failure, mean age 73.7, majority White (94.4%) | 158 care partners, mean age 58.5, majority White (93.6%), majority women (73%), average education level 12.9 years | Majority spouse (50%) | Qualitative interview 1 day before discharge, telephone interview 2 weeks and months post-discharge |

| Bull et al. (2017) | Mixed-method, pre-post quasi experimental design Level 3B | Orthopaedic unit of Veterans Affairs Medical Center | 34 patients recovering from knee arthroplasty, 6 women, 28 men, mean age 76.1, mean education years 12.7 |

39 care partners, mean age 63.9, majority White (94.9%), majority women (89.7%), average education years 14 | Majority spouse (62%) | Family Caregiver Delirium Knowledge Questionnaire |

| Coleman et al. (2015) | Prospective cohort study Level 3B | 253 bed rural, acute care hospital from cardiovascular, general medical-surgical, and orthopaedic units | 83 Medicare patients, aged 65 and older | 83 care partners, mean age 65.7, majority White (96%), majority women (83%) | Majority spouse (80%) | Family Caregiver Activation Assessment |

| Havyer et al. (2017) | Qualitative survey Level 5 | Veterans Affairs Medical Center | 1,109 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer, aged 65+ | 417 care partners, mean age 60.7, majority White (76.6%), majority women (90.3%), majority education less than high school (58.7%) | Majority spouse (61%) | Self-created survey |

| Hendrix et al. (2011) | Time series Level 4 | 4 medical surgical units at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, NC | 50 patients considered ‘frail’, 4% women, 96% men, aged 60–69 (70%), 70–79 (22%), 80+ (8%), majority White 72% | 50 care partners, majority age 60–69 (49%), majority White (80%), majority women (92%), majority education high school or less (40%) | Majority spouse (72%) | Family Preparedness Scale |

| Hendrix et al. (2013) | One group pre-test post-test Level 3B | Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, NC | 47 patients diagnosed conditions with Genitourinary including renal (23%) Cardiovascular (19%) Gastrointestinal (13%) Neurological (13%) Pulmonary (13%) Other (19%), 4% women, 96% men | 15 care partners | N/A | Family Preparedness Scale |

| Li et al. (2003) | Randomised control trial Level IB | 720-bed academic medical centre in upstate New York | Care group 25 patients, mean age 75.9, 60% women, 40% men Comparison group 24 patients, mean age 76, 71% women, 29% men | Care group 25 care partners, mean age 63.6, majority women (68%), majority education completed college (32%) Comparison group 24 care partners, mean age 57.9, majority women (58%), majority education completed high school (33%) |

N/A | Family Preparedness Scale |

| Li et al. (2012) | Randomised block design with repeated measures Level 2B | Urban medical centre | 202 patients, 52.3% women, 47.7% men, mean age 75.74, Race: White (89.6%), African American (8.1 %) | 202 care partners, mean age 60.76, majority women (71.4%), majority White (89,4%), majority education above high school (74.9%) | Equivalent spouse and non-spouse | Family Preparedness Scale |

| Paulson et al. (2016) | Descriptive survey Level 5 | Inpatient medicine and cute care of the elderly unit (ACE) of Vanderbilt University Medical Center | Delirium symptoms | N/A | N/A | Quantitative survey with one narrative response |

| Reinhard et al. (2017) | One group pre-test/post-test with nonequivalent groups Level 3B | 8 NICHE hospitals ranging from small to large, teaching, and non-teaching | Intervention group 326 patients, majority White (54.1%) Comparison group 370 patients, majority White (89.2%) |

Intervention group 184 care partners Comparison group 69 care partners |

N/A | Family/Caregiving Experience Survey |

| Rosenbloom-Bruton et al. (2010) | Descriptive exploratory design Level 5 | 900-bed inpatient acute, academic medical centre | 15 patients, mean age 77.8, with congestive heart failure (26.7%), Pneumonia (26.7%), Renal failure (26.7%) Agina, chest pain (6.7%) Dehydration (6.7%) Hypoglycemia (6.7%), 66.7% women, 33.3% men |

15 care partners, mean age 61.2, majority women (73.3%), majority education high school or equivalent (60%) | Majority adult child (40%) | Family Caregiver Tracking form and written questionnaire |

| Stone (2013) | Pre-test/post-test design Level 3B |

45-bed inpatient rehabilitation centre | 70 patients with stroke (51.4%), orthopaedic (18.6%), brain injury (71.0%), spinal cord (8.6%), amputation (4.3%) or general (4.3%), 62.3% women, 35.7% men | 70 care partners, majority age 45-54 (25.7%), majority women (82.9%) | Majority child (50%) | Family Preparedness Scale |

N/A = not applicable.

Health care provider type.

Nurses most frequently delivered the education or skills training to care partners (n = 11), followed by social workers (n = 3) and physicians (n = 2). One study in particular did not involve any providers in the delivery of education and skills training; rather, research assistants implemented the intervention (Li et al., 2012).

Timing of education and skills training.

Education and skills training occurred at multiple points of care including pre-hospitalisation (n = 1), throughout the hospital stay only (n = 3), across hospital stay and post-hospitalisation (n = 6) and at discharge only (n = 2). Most education and skills training occurred within 1–3 days before the patient leaving the hospital.

Delivery mode of education and skills training.

Studies used a combination of face-to-face conversation, written text (including brochures and handouts), videotapes, audiotapes, telephone calls and interactive websites when delivering education and skills training to care partners. The most utilised delivery mode was face-to-face conversation (n = 8), followed by written text (n = 6), and digital (DVD, website, audiotape, email) (n = 5). It was less common for studies to utilise multiple modes of training (n = 4) compared to single modes (n = 8) when delivering education and skills training.

Content type of education and skills training.

Information conveyed to care partners during education and skills training included recognition and treatment of delirium symptoms (n = 3), medication management (n = 6), signs of infection or red flags (n = 2), pain management (n = 1), wound care (n = 1), surgical precautions (n = 1), medical device management (n = 1), hospital to home transitions (n = 4) and location and utilisation of community-based resources (n = 2).

Care partner outcomes of education and skills training.

Three studies, two descriptive and one quasi-experimental, determined that care partner-centred intervention programmes are feasible for implementation in acute care and for increasing care partner engagement and experience (Paulson et al., 2016; Reinhard et al., 2017; Rosenbloom-Brunton et al., 2010). Two experimental studies examined a self-management programme and found significant effects on care partner preparedness as compared to those who received standard care (Li et al., 2003, 2012). Similarly, five studies, four quasi-experimental and one observational, determined that education and skills training interventions targeted at care partners can increase preparedness, satisfaction, self-efficacy and overall health and well-being (Bull et al., 2000; Coleman et al., 2015; Hendrix et al., 2011; Stone, 2013) Hendrix et al. (2013) was the only article that found no significant improvement in care partner burden or preparedness after a hospital transition programme (Hendrix et al., 2013). One study found that routine care provides inadequate care partner training, which can lead to low self-efficacy (Havyer et al., 2017).

Synthesis of results related to IDEAL recommendations.

Table 3 illustrates the IDEAL discharge planning recommendations identified in the 12 studies. The most prominently identified recommendation was that education and skills training should occur throughout the patient’s hospitalisation (n = 9), followed by diverse content for care partner education and training on how to help a loved one post-discharge (n = 7), incorporating more than one health care provider as part of the discharge team (n = 5) and using multiple modes of delivery to communicate information (n = 5).

Table 3.

Included studies mapped on IDEAL framework.

| Recommendations for education and skills training based on IDEAL framework | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Author (year) | Interprofessional care team | Education and skills training throughout hospital stay | Multiple modes of education and skills training delivery | Education and skills training involved diverse content |

| Bull et al. (2000) | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Bull et al. (2017) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Coleman et al. (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Havxer et al. (2017) | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Hendrix et al. (2011) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Hendrix et al. (2013) | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ |

| Li et al. (2003) | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Li et al. (2012) | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Paulson et al. (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Reinhard et al. (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Rosenbloom-Bruton et al. (2010) | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Stone (2013) | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

✓ = include; ✕ = not included.

Discussion

This scoping review explored the key characteristics of education and skills training used with care partners of hospitalised older adults. Four important results emerged from the review: (1) one health care provider typically takes the lead in providing education and skills training to care partners; (2) education and skills training often occur close to, or at discharge; (3) written or digital modes are frequently used to deliver education and skills training and (4) the content of education and skills training is often focussed on complex medical and nursing tasks. Results from the review suggest that care partner education and skills training are inconsistent in following available practice recommendations for the discharge process. Recommendations include the following: (1) be interprofessional; (2) deliver education and skills training throughout the hospital process; (3) use not only written and verbal modes of delivery, but also teach-back and return demonstration1 and (4) include diverse content areas related to the patient’s condition. When these recommendations are not followed, there is an increased risk of care partners feeling unprepared to fulfil their caregiving responsibilities for older adults once they return home from the hospital (Coleman and Roman, 2015).

Nurses primarily deliver education and skills training to care partners during hospital care in preparation for discharge. One possible explanation for nurses serving as the primary provider for delivering education and skills training is that the profession has historically interacted more frequently with care partners and patients and represents the largest part of the health care workforce in the USA (Skärsäter et al., 2018; Smiley et al., 2018). In line with practice recommendations for discharge planning, many hospitals are trying to adopt a more interprofessional collaborative approach to care, whereby multiple providers are encouraged or required to be involved in education and skills training delivery to patients and their care partners (Ma et al., 2018). However, while providers support working as a cohesive team, few are actually able to implement an interprofessional model due to lack of collaboration and coordination (Jansen, 2008). Differentiating education and skills training content by provider type could help explicate important discipline-specific scope of practice variations. For example, nurses are skilled in delivery of wound care management and dispensing of medications, whereas occupational therapy providers are skilled in enhancing participation in roles, habits and daily routines and physicians experts in diagnostics and coordinated management of disease (American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2014; American Medical Association, n.d.; American Nurses Association, 2015).

Most education and skills training occurs close to or after discharge despite recommendations suggesting it begin before or at admission (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.). Cognitive learning theories suggest that education and skills training should be spread across multiple care points (i.e. admission, during stay, discharge and post-discharge) to prevent care partners from feeling overloaded with information and allow them time to process new materials (Smith and Scarf, 2017). Several studies in this review emphasised that education and skills training could also occur prior to an older adult’s hospitalisation to better prepare families and prevent adverse events or injuries from occurring. For example, one study trained care partners to recognise ‘red flag’ symptoms before an orthopaedic procedure which resulted in increased knowledge retention and satisfaction (Bull et al., 2017).

Aligning with discharge planning recommendations, most education and skills training in the included studies used a combination of face-to-face, written and digital delivery modes. Verbal conversation with patients and care partners occurred most frequently. Face-to-face conversation did not include teach-back or return demonstration (see Note 1) opportunities, which have been shown to reinforce and solidify patient education for older adults (Yen and Leasure, 2019). Teach-back or return demonstration techniques also involve hands-on learning, which is typically the preferred mode of delivery for care partners (Hunt and Reinhard, 2015). Education and skills training that incorporates different modes of communication to present content is considered multimodal (Paivio, 1990).

Studies have reported that a multimodal education and training style can meet the learning needs of diverse groups, including individuals with various cognitive and health literacy abilities and learning styles, and older adults (Dillon and Jobst, 2005; Moreno and Mayer, 2007; Munteanu and Salah, 2017). This review identified five studies that examined the impact of multiple modes of education and skills training delivery on care partner preparedness for hospital discharge (Bull et al., 2000: 200; Li et al., 2003, 2012; Reinhard et al., 2017; Rosenbloom-Brunton et al., 2010). Similar studies have found multimodal education and skills training can help care partners retain information which highlights the need to ensure educational material is accessible to diverse groups (Best, 2001; Messner et al., 2005; Murphy and Davis, 1997).

Few studies included education and skills training targeting daily activities (e.g. bathing, dressing, cooking and cleaning). Content that was most frequently addressed during education and skills training were complex medical and nursing tasks and symptom identification. Without adequate training on how to complete daily activities, care partner’s demand and burden increase in correlation with patient health decline (Boyd et al., 2008). One possible explanation for the lack of appropriate education and skill training on daily activities is that hospital care is primarily focussed on providing patients diagnostic testing, surgery or intensive medical treatments. Following hospital care, older adults often transition to skilled nursing facilities, outpatient rehabilitation programmes or home care where they may learn more about how to manage and complete daily activities.

Another content area that was noticeably absent from the included studies was lack of counselling on coping strategies for care partners. One possible explanation for this is that the delivery of services in the included studies was directed at improving the education and skills training of care partners to fulfil the patient needs, not the care partner’s needs. However, if the care partners’ health and well-being are not addressed, they may become burdened and unable to provide effective care for older adults (Hunt and Reinhard, 2015).

There exist system-wide barriers and facilitators to providing the recommended education and skills training. In particular, there is resistance to change from providers and often limited resources, including finances, reimbursement incentives, time and space, available for providers to educate and train care partners in addition to their patient-care responsibilities (Bélanger et al., 2018; Leighton et al., 2020). However, the implementation of the CARE Act has been shown to reduce health care resources and improve care partners caregiving skills, outcomes that have the potential to serve as a nation-wide facilitator to positive change (Rodakowski et al., 2021).

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths of this review. We used a well-cited framework to guide the scoping review process (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). To better understand current practice trends in care partner education and skills training, we also used the IDEAL discharge planning guide to direct our data extraction, analysis and synthesis (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.). In addition, two independent reviewers and one consultant reviewer on our team conducted data extraction and analysis to decrease the risk of bias and increase the reliability and validity of our results.

There are, however, several limitations, to this review. There is the possibility that studies that met our inclusion criteria were missed due to inconsistent use of search strategy terminology and a limited number of databases searched. This review also left out certain populations of care partners and patients that could contribute to the literature on education and skills training including patients with mental health diagnoses or those receiving palliative care. In addition, how education and skills training may vary based on patient condition was not examined. Finally, because scoping reviews do not require a formal quality appraisal of research, the rigour of included studies cannot be attested. Given these limitations, it is essential that more research focus on the education and skills training delivered to care partners during hospital care.

Conclusion

This scoping review suggests that care partner education and skills training are an important part of the discharge planning process for hospitalised older adults. Effective education and skills training are needed to ensure care partners are prepared to meet older adults’ needs once they return home from the hospital. However, several care partner education and skills training gaps were identified in the discharge planning process, including a lack of interprofessional collaborative approaches, delivery modes and timing of delivery and diverse content related to the patient’s condition and the care partners’ responsibilities. Researchers, health care administrators and health providers can use this information to develop, test and implement interventions and policies focused on increasing care partner preparedness for assuming caregiving responsibilities post-hospital discharge via education and skills training.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support for this research was provided by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the university of Wisconsin-Madison with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Teach back and return demonstration are teaching strategies in which someone is asked to state or show what they have learned in their own words or actions.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (n.d.) Care Transitions from Hospital to Home: IDEAL Discharge Planning. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/patients-families/engagingfamilies/strategy4/index.html

- AARP (2014) New state law to help family caregivers. Available at: https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/caregiving-advocacy/info-2014/aarp-creates-model-state-bill.html (accessed 19 July 2021).

- American Journal of Occupational Therapy (2014) Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd Edition). American Journal of Occupational Therapy 68(Suppl. 1): S1–S48. [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association (n.d.) Scope of Practice. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice (accessed 4 March 2021)

- American Nurses Association (2015) Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. Available at: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T–JS&CSC–Y&NEWS–N&PAGE–booktext&D–books2&AN–01884402/3rd_Edition (accessed 27 September 2020)

- Arksey H and O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1): 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger L, Desmartis M and Coulombe M (2018) Barriers and facilitators to family participation in the care of their hospitalized loved ones. Patient Experience Journal 5(1): 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bell JF, Whitney RL and Young HM (2019) Family caregiving in serious illness in the United States: Recommendations to support an invisible workforce. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 67(S2): S451–S456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JT (2001) Effective teaching for the elderly: Back to basics. Orthopaedic Nursing 20(3): 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. (2008) Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness: Functional recovery after hospitalization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56(12): 2171–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull MJ, Boaz L, Maadooliat M, et al. (2017) Preparing family caregivers to recognize delirium symptoms in older adults after elective hip or knee arthroplasty. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 65(1): e13–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull MJ, Hansen HE and Gross CR (2000) A professional-patient partnership model of discharge planning with elders hospitalized with heart failure. Applied Nursing Research 13(1): 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J, Roth DL, Riffin C, et al. (2019) Factors associated with receipt of training among caregivers of older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(6): 833–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2012) Discharge Planning. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://seniorsresourceguide.com/directories/National/FamilyDischargePlanning/docs/Discharge-Planning-Booklet-ICN908184.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA and Roman SP (2015) Family caregivers’ experiences during transitions out of hospital. Journal for Healthcare Quality: Official Publication of the National Association for Healthcare Quality 37(1): 12 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, Roman SP, Hall KA, et al. (2015) Enhancing the care transitions intervention protocol to better address the needs of family caregivers. Journal for Healthcare Quality: Official Publication of the National Association for Healthcare Quality 37(1): 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon A and Jobst J (2005) Multimedia learning with hypermedia. In: Mayer R (ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 569–588. [Google Scholar]

- Gorina Y, Pratt LA, Kramarow EA, et al. (2015) Hospitalization, readmission, and death experience of non-institutionalized Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 and over. National Health Statistics Reports 84: 1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havyer RD, van Ryn M, Wilson PM, et al. (2017) The effect of routine training on the self-efficacy of informal caregivers of colorectal cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 25(4): 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix CC, Hastings SN, Van Houtven C, et al. (2011) Pilot study: Individualized training for caregivers of hospitalized older veterans. Nursing Research 60(6): 436–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix CC, Tepfer S, Forest S, et al. (2013) Transitional Care Partners: A hospital-to-home support for older adults and their caregivers: Transitional Care Partners. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners 25(8): 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines AL, Barrett ML, Jiang HJ, et al. (2006) Conditions with the largest number of adult hospital read-missions by payer, 2011: Statistical brief #172. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk206781#free-full-text [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt G and Reinhard SC (2015) Caregivers of Older Adults: A Focused Look at Those Caring for Someone 50+. AARP Public Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregivers-of-older-adults-focused-look.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jansen L (2008) Collaborative and interdisciplinary health care teams: Ready or not? Journal of Professional Nursing 24(4): 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton C, Fields B, Rodakowski JL, et al. (2020) A multisite case study of caregiver advise, record, enable act implementation. The Gerontologist 60(4): 776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Melnyk BM, McCann R, et al. (2003) Creating avenues for relative empowerment (CARE): A pilot test of an intervention to improve outcomes of hospitalized elders and family caregivers. Research in Nursing & Health 26(4): 284–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Powers BA, Melnyk BM, et al. (2012) Randomized controlled trial of CARE: An intervention to improve outcomes of hospitalized elders and family caregivers. Research in Nursing & Health 35(5): 533–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Park SH and Shang J (2018) Inter- and intra-disciplinary collaboration and patient safety outcomes in U.S. acute care hospital units: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 85: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner E, Curci K and Reck D (2005) Effectiveness of a patient education brochure in the emergency department. Topics in Emergency Medicine 27(4): s251–s255. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno R and Mayer R (2007) Interactive multimodal learning environments: Special issue on interactive learning environments: Contemporary issues and trends. Educational Psychology Review 19(3): 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu C and Salah AA (2017) Multimodal technologies for seniors: Challenges and opportunities. In: Oviatt S, Schuller B, Cohen PR, et al. (eds) The Handbook of Multimodal-Multisensor Interfaces: Foundations, User Modeling, and Common Modality Combinations – Volume 1. New York: ACM, pp. 319–362. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PW and Davis TC (1997) When low literacy blocks compliance. RN 60(10): 58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A (1990) Mental Representations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson CM, Monroe T, McDougall GJ, et al. (2016) A family-focused delirium educational initiative with practice and research implications. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education 37(1): 4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG and Watkins MP (2009) Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Capezuti E, Bricoli B, et al. (2017) Feasibility of a family-centered hospital intervention. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 43(6): 9 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Feinberg LF, Houser A, et al. (2019) Valuing the Invaluable: 2019 Update: Charting a Path Forward, 14 November. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Rodakowski J, Leighton C, Martsolf GR, et al. (2021) Caring for family caregivers: Perceptions of CARE act compliance and implementation. Quality Management in Healthcare 30(1): 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom-Brunton DA, Henneman EA and Inouye SK (2010) Feasibility of family participation in a delirium prevention program for hospitalized older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 36(9): 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skärsäter I, Keogh B, Doyle L, et al. (2018) Advancing the knowledge, skills and attitudes of mental health nurses working with families and caregivers: A critical review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice 32: 138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley RA, Lauer P, Bienemy C, et al. (2018) The 2017 national nursing workforce survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation 9(3): S1–S88. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD and Scarf D (2017) Spacing repetitions over long timescales: A review and a reconsolidation explanation. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone K (2013) Enhancing preparedness and satisfaction of caregivers of patients discharged from an inpatient rehabilitation facility using an interactive website. Rehabilitation Nursing: The Official Journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses 39(2): 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen PH and Leasure AR (2019) Use and effectiveness of the teach-back method in patient education and health outcomes. Federal Practitioner 36(6): 284–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]