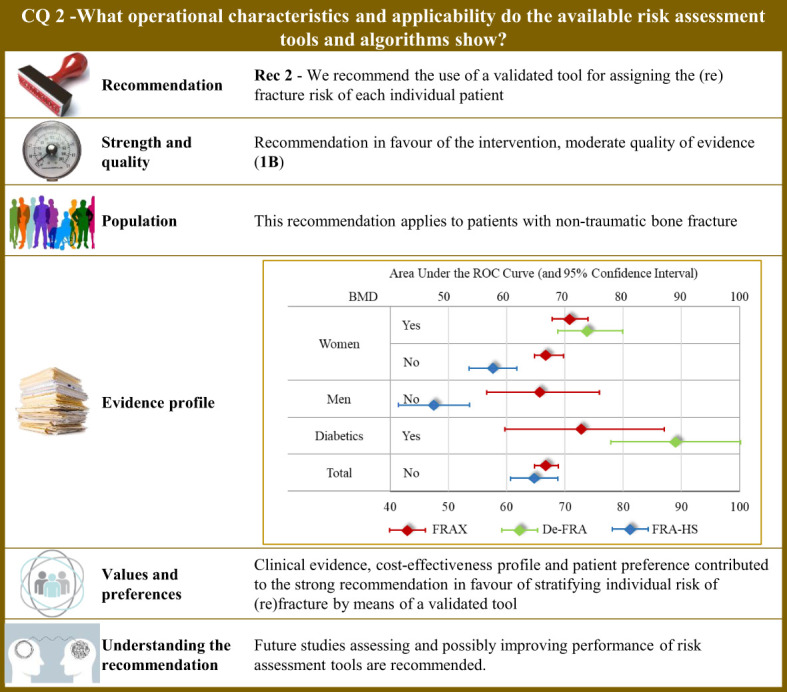

Figure 2.

Visual summary for CQ2 (What operational characteristics and applicability do the available risk assessment tools and algorithms show)?. Rationale. The most common tool used worldwide for assessing the fracture risk is the so-called FRAX®, which was developed at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom, and is based on individual patient models that integrate the risk associated with several individual features (i.e., gender, age, body mass index, personal history of fragility fracture; parental history of proximal femur fracture; current smoking status; prolonged use of glucocorticoids; rheumatoid arthritis; secondary causes of osteoporosis; and alcohol consumption ≥ 3 units per day), with or without including bone mineral density at the femoral neck (106). The model was externally validated (107) and calibrated from country-specific fracture data covering more than 80% of the world population (108). The FRAX® algorithm give the 10-year probability of fracture (106). Although the FRAX® tool is the most popular predictive tool, it nevertheless presents some application concerns, and above all access problems for regulatory use. For this reason, national versions have been developed such as the QFracture algorithm to predict risk of osteoporotic fracture in primary care in the UK (109). In Italy, three algorithms have been developed, nominally: (i) the DeFRA developed by the Italian Society for Osteoporosis, Mineral Metabolism and Bone Diseases in collaboration with the Italian Society of Rheumatology (110), and made available online (111); (ii) its updated version (DeFRAcalc79) defined according to drug reimbursement rules from the Italian Drug Agency (112); (iii) and the FRActure Health Search (FRA-HS) developed by the Italian Society of General Medicine and Primary Care (113). As studies directly comparing reliability and applicability of available tools are lacking, a systematic revision of literature was carried out for obtaining and comparing meta-analytic estimates of discriminatory powers through the AUC (area under the receiver operating curve) (114). Through the updating of the NICE guidelines (115), our systematic review included 47 original papers investigating operative characteristics of FRAX® (116–162) and added three papers pertaining Italian instruments (two for DeFRA (163, 164) and one for FRA-HS (165)). Operative characteristics pertain the 10-year predicted and observed fracture risk (major osteoporotic or proximal femur) in all the included papers. Tools performance. Meta-analytic AUC estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) for FRAX were 0.66 (0.57 to 0.76) and 0.67 (0.65 to 0.70) in women and men, respectively. By including body mineral density among the considered items, the AUC of FRAX® improved to 0.71 (0.68 to 0.74) and 0.73 (0.60 to 0.87) in women and diabetics, respectively. DeFRA had better performance than FRAX® for both women (0.74, 0.69 to 0.80) and diabetics (0.89, 0.78 to 1.00). Conversely, FRA-HS discriminated worse than other tools with the AUC estimates 0.58 (0.54 to 0.62) and 0.48 (0.42 to 0.54) in women and men, respectively. Clinical and value issues. Ten-year fracture risk perceived by patients and that estimated by the predictive tool (specifically by FRAX®) was found to be highly disagreeing among patients at high fracture risk, women, elderly, and patients treated with anti-osteoporotic medications or calcium/vitamin D (166), thus making implementation of fracture prediction tools in clinical practice highly to be hoped for. Efficient screening strategies may support fragility fracture prevention as shown by a Sweden study that administered the FRAX® to postmenopausal women via e-mail, online or screening mammography (167). Patients at high risk of fracture should be earlier identified to reduce mortality, comorbidities, and costs (177). Suitable cost-effectiveness profiles for fracture risk screening (169), and for consequent therapy of high-risk patients with any anti-osteoporotic treatment (170–176), and other drugs (176) were consistently reported from several European countries. Understanding the recommendation. Although clinical evidence, cost-effectiveness profile, and patient’s preference contributed to the strong recommendation in favours of stratifying the individual risk of (re)fracture, concerns persist about quality of evidence of studies investigating predictivity of available tools, including FRAX®. Although FRAX® might be used in any healthcare settings (168, 177), cautions should be taken in its use in specific countries by adopting tools built and validated in the target population. Future studies assessing and possibly improving performance of risk assessment tools are recommended.