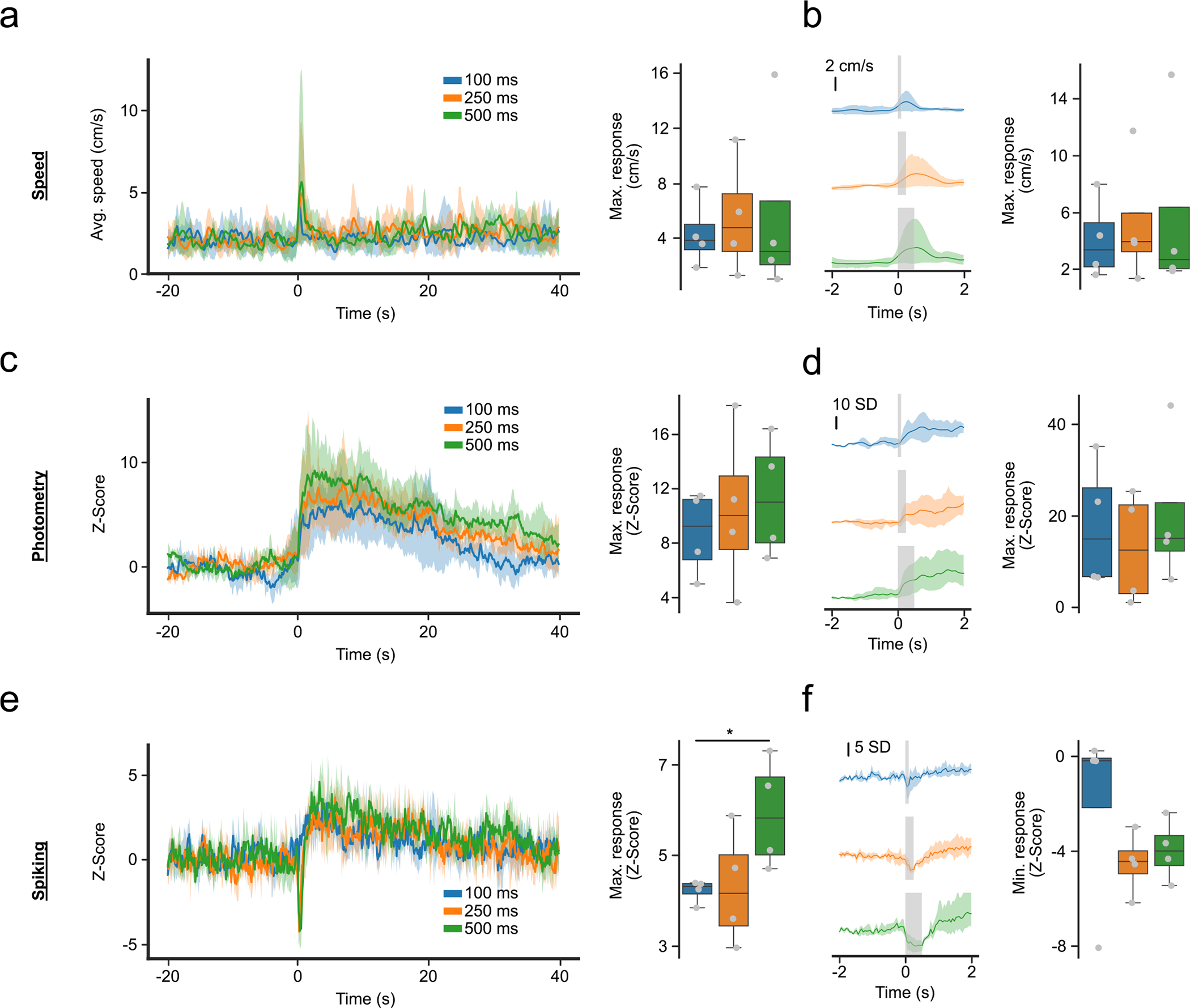

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Photometry, and spiking activity, and locomotor activity reflect distinct responses around foot shocks.

(a) Motor response around 0.7 mA foot shocks of different length. (Left) Average response from −20 to 40 seconds. (Right) Maximum response from 0 to 5 seconds, time-locked to foot shock (F-Value = 0.64, p-value = 0.558). (b) Close-up of (a), showing motor response in a short time-interval around foot shock. (Left) Average response from −2 to 2 seconds. (Right) Maximum response from 0 to 1 second, excluding the stimulus time (F-value = 0.61, p-value = 0.572). (c) Same as (a) but for the photometry response. (Right) F-value = 0.93, p-value = 0.445. (d) Same as (b) but for photometry response. (Right) F-value = 1.89, p-value = 0.231. (e) Same as (a,c) for spiking activity. (Right) F-value = 8.57, p-value = 0.017 (f) Same as (b,d) but for spiking activity and showing the minimum response instead of maximum. (Right) F-value = 1.38, p-value = 0.321. For quantification, we ran repeated measures ANOVAs with post-hoc two-tailed paired t-tests with bonferroni corrections (n = 4 mice). * denotes p < 0.05 after correction. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals. Box plots central value denotes the median, box bounds denote upper and lower quartiles and whiskers denote ±1.5 interquartile range.